Chapter 14

CHURCH AND SOCIETY IN WESTERN CHRISTENDOM

Medieval Christendom’s boundaries continued to grow until the fourteenth century. The conversion of Franks, Lombards, Angles, Saxons, and Visigoths in the sixth and seventh centuries was followed by the conversion of Frisians and Hessian Germans in the seventh and eighth centuries. The forcible conversion of the Saxons by Charlemagne occurred at the end of the eighth century. The conversion of northern Germans and western Slavs took place during the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries. And finally the Baltic peoples were incorporated into Christendom in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The Scandinavian Kings were very instrumental in the Christianization of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Danish King Sven (d. 1014) and his son Canute (d. 1035) brought missionaries into Denmark, while two Norwegian Kings, both named Olaf, did the same for Norway in the eleventh century. Paganism held out longest in Sweden, but with the conversion of its neighbors Denmark, Norway, and Poland, pressures mounted, and by the end of the eleventh century most of the resistance was overcome. In 1164 the Pope made Uppsala a metropolitan see for all Sweden.

During the great migrations the Slavs spread across central Europe and occupied the wide stretch of land from the Dnieper to the Elbe and Saale rivers, including Bohemia. Cyril (d. 869) and Methodius (d. 885) had some success as missionaries to the Slavs in Moravia in the ninth century, and Cyril invented the Slavonic alphabet by combining Greek letters with some new ones in order to provide the Slavs with a liturgical language.

But it was not until the tenth century that Christianity made real progress among the Slavic peoples. The Bohemian princes looked to Germany for protection against the fierce Magyar invaders and were therefore influenced toward Christianity; in 973 a bishopric for Bohemia was erected at Prague. Thence it spread among the Poles, whose renowned Prince Mieszko (d. 990) firmly established the Polish Kingdom and presented his realm to St. Peter and the Pope. A papal charter of the year 1000 gave Poland its own ecclesiastical organization under a metropolitan at Gnesen. In this way Poland was brought into the Western orbit. The conversion of the Hungarians was likewise carried out during the tenth and eleventh centuries.

For a time it looked as if Russia might follow Poland and Hungary into the papal orbit. Founded as the Kievan state in the ninth century by Viking traders who gradually integrated with their Slavic subjects, Russia received missionaries from both East and West as early as the ninth century. But it was only under Vladimir (d. 1015) that Christianity was officially adopted. After conversing with emissaries of the Pope and Patriarch as well as with Moslems and Jews, the Russian prince weighed the pros and cons and finally decided to accept baptism in the Byzantine Church—a decision of vast import for the religious future of Russia. As a derivative Church of the Byzantine, Russia followed Constantinople into schism from Rome in the next century. The last Eastern Europeans to accept Christianity were the Baltic people of Livonia, Prussia, and Lithuania in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

HOW DID THE Church go about ministering to the spiritual as well as temporal needs of its vast conglomeration of members—estimated at the time of Innocent III to number some seventy million? The ecclesiastical organization that embraced them all (except for a tiny minority of Jews) was divided into some four hundred dioceses, each ruled by a bishop or archbishop who was canonically subject to the Pope, although often he was more an agent of the King. Besides being a great landowner and feudal overlord, the bishop or archbishop was judge and legislator, head of the local ecclesiastical hierarchy. He was often related to the most powerful families in his region and nominated to the office as a reward for his administrative talents or outstanding service in secular government, for Kings as a rule depended on the clergy to staff their civil service, since lay education was rare throughout the Middle Ages. These clerical civil servants were often in minor orders and were only ordained as priests upon being appointed to a bishopric. A typical example would be a fourteenth-century English bishop, William of Wykeham. He built an outstanding career in the royal service as head clerk of the office of works—a post he practically created. He was so busy as privy councilor that the chronicler Froissart applied to him the biblical verse, “Everything was done through him and without him nothing was done.”55 When elected bishop of Winchester in 1367 William was immediately made chancellor of the realm as well.

The tasks of the bishop were many and varied: administrative, judicial, and spiritual. One of his chief duties was to conduct visitations of the religious institutions in his diocese. He usually held the visitation in the local church and would summon the clergy of the area and several laymen to attend. After verifying the credentials of the clergy, the bishop would interrogate the laymen about the behavior of the clergy—whether they performed their duties properly, whether they wore the clerical dress, whether they frequented taverns or played dice. And the laity too had to answer for their conduct. Finally, the bishop would inspect the physical state of the church and the condition of its appurtenances. The bishop also held synods of his clergy, at which time he laid down the law on the great variety of matters subject to his jurisdiction. His greatest power, and one that was often a cause of lay resentment, was his law court, where he exercised jurisdiction on a wide assortment of matters, including moral behavior, marriage, and last testaments.

One of his most important spiritual duties was ordaining men to the priesthood. Since there were no seminaries for the training of candidates (these were only prescribed by the Council of Trent), those who wished ordination simply presented themselves three days before the ceremony and took a three-day oral exam. If they could show that they had a firm grasp of the Catholic faith and could express it in simple language, they were admitted to ordination, provided they were of canonical age (twenty-four years for the priesthood) and were not disqualified by reason of servile birth, illegitimacy, or bodily defects.

Each diocese was subdivided into parishes, which were usually staffed by the so-called secular priests. The priest shared in the bishop’s sacred powers of consecrating and administering the sacraments. Unlike the bishop, he was usually drawn from the lower classes. Once appointed to the parish by the bishop or lay patron or, as sometimes happened, elected by the congregation, he had duties much the same as today: saying Mass for the faithful, especially on Sundays, baptizing, hearing confessions, attending to the sick, and burying the dead. It was his special duty also to exhort his parishioners to care for the poor. He might also act as chaplain to a parish guild, which might be partly fraternal and partly devotional in character.

The local priest was often hardly distinguishable from his parishioners, even though in theory and theology there was supposed to be a sharp separation. According to the Gregorian concept the priests were to form a disciplined army moving completely in step under the Pope, set off from all profane occupations, with their special uniform, the long cassock (a relic of the Roman toga), and ruling over an obedient and receptive laity composed of kings, lords, and peasants alike. And one of the main objectives of the Gregorian reformers was to restore the rule of celibacy, which by the eleventh century had fallen into decay. Their zeal against clerical marriage was prompted in part by their realization of how marriage tended to assimilate the clergy to their lay surroundings. They had considerable success in restoring celibacy and bringing greater clarity and precision to Church legislation in the matter. At the Second Lateran Council (1139) they finally managed to have all clerical marriages declared null and void.

But just how effective these laws were is open to question. Clerical concubinage apparently remained widespread during the Middle Ages, and there always seemed to be a plentiful supply of bastard children of priests. One author found that on one day (July 22, 1342)—chosen at random—the Curia issued 614 dispensations for marital impediments, 484 of which had to do with the bastards of priests.56 Nevertheless, infractions of the law by bishops seemed to have been comparatively rare.

It was at the Mass that the separation of clergy from people was made dramatically evident. While the Mass had retained its basic meal structure, even in the early centuries it began to move away from its original character as an action of the whole community. This tendency was intensified during the early Middle Ages. The people were gradually excluded from all participation, and the Mass became exclusively the priest’s business, with the people reduced to the role of spectators. In the medieval Mass the priest no longer wore his ordinary street clothes, as he once did, but glided into the sanctuary draped in a heavily embroidered chasuble and began to whisper the prayers in a language no longer understood by the people. They stood at a distance, separated from him by a heavy railing, which emphasized the sacredness of the sanctuary. No longer were they allowed to bring up their ordinary bread for consecration; the priest consecrated unleavened bread already prepared in coinlike form. Nor were they allowed to take the wafer in their hands, standing as they once did; now they had to kneel and receive it on the tongue, while the chalice was withheld from them.

The transcendental, awesome, and mysterious nature of the Mass was allowed to blot out almost completely the original spirit of community participation. It was something that happened at the altar, it was the “epiphany of God.” It was something you watched. The various actions of the priest were no longer intelligible in this context, so they were given mystical and allegorical significance. The Mass became a kind of pageant representing the life, death, and sufferings of Christ. The “Gloria” was sung to remind one of the angels announcing the birth of Christ. Then came the reading of the gospel— the tale of his public life and preaching. This was followed by silent prayers of the priest, who signified Christ praying in the garden of Gethsemane. When he stretched out his arms, he represented Christ suffering on the cross. Five times he made the sign of the cross over the chalice and host in order to signify the five wounds. When he knelt it was to signify Christ’s death, and when he stood up again, it was to signify his resurrection.

Only monks, nuns, and priests received communion frequently. The main object of the layman in coming to Mass was to see the consecrated wafer, and for many the climax came when the priest elevated it after the Consecration. A warning bell was rung beforehand to alert the faithful, many of whom would wander around town going from church to church just to be present at the elevation. Sometimes they would pay the priest a special stipend just to hold the host up higher and for a longer time, and some even engaged in lawsuits in order to get the best place for viewing the host. This attitude gave rise to various devotions that focused on the host. The entire town would come out on such feasts as Corpus Christi in June, when the priest would carry the host through the town encased in a glittering gold monstrance.

Besides the secular clergy, whose main responsibility was the care of the parishes, there were (and still are) a large body of priests, monks, brothers, and nuns who lived in monasteries and religious houses and were called regular as distinct from secular. The term derived from the Latin word regula, or rule, and was used because these religious followed a common rule of life based on the observance of the three vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

The regulars were further subdivided into monks and friars, each group having female counterparts. The friars made their appearance in history much later than the monks.

In spite of a brief reform led by Benedict, abbot of Aniane (d. 821), the monasteries fell prey to the same evils and disorders that afflicted secular society during the breakdown of the Carolingian Empire. Many of them fell into complete decadence and in some cases were hardly more than strongholds of brigands. But a powerful movement of reform began at the monastery of Cluny in Burgundy, where a series of strong abbots—Odo (d. 941), Mayeul (d. 994), and Odilo (d. 1048)—restored the strict observance of the Rule of St. Benedict and provided a model of reform that spread to numerous other monasteries in the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, England, and Germany.

Until the Cluny reform there was no such thing as a monastic “order.” Each monastery was an independent, self-governing unit immediately subject to the Pope or local bishop. But the Cluniacs introduced a new concept: The various monasteries were grouped together in a religious “order” under the centralized authority of the abbot of Cluny, to whom they owed absolute obedience. At the same time they enjoyed complete exemption from the authority of the local bishop. The Cluny Order by the year 1100 embraced some two thousand abbeys, priories, and cells.

The Cluny reform made an important contribution to the progress of spirituality in the medieval Church. It was also an outstanding champion of the papal monarchy and was no doubt the chief spiritual power behind the Gregorian reform and its struggle for the liberation of the Church from control by the laity. It is no coincidence that Gregory VII himself, as well as his dynamic successors Urban II and Paschal II, was a Cluniac.

The success of the Cluny reform was due to the consistency with which its leaders insisted upon strict observance of the Rule of St. Benedict, with its moderate asceticism: silence in church and cloister, exclusion of meat from the diet, and elimination of private property. As time passed, however, the monks acquired extensive tracts of land, which they ornamented with magnificent architecture.

A certain spiritual mediocrity began to manifest itself, and a new group of reformers arose within the order who were unhappy with the growing luxury. Under Robert, the abbot of Molesmes, they migrated in 1098 to Cîteaux, a desolate spot in the diocese of Châlons in France. This move marked the beginning of a new monastic order, the Cistercians, whose third abbot and true founder was an English saint and mystic, Stephen Harding (d. 1134), a monk who combined exceptional administrative gifts with a passionate love of poverty. But the decisive event in its history was the arrival at Cîteaux in 1113 of Bernard, a brilliant nobleman of twenty-two who brought with him a band of thirty disciples, including his own brothers. Three years later he himself founded the daughter abbey of Clairvaux and remained its abbot until his death in 1153. Henceforth as preacher, author, and guide of souls, he was the chief force behind the spiritual revival of the twelfth century as well as being one of the most illustrious statesmen of the time.

Under the influence of such leaders, the white-and-black-robed Cistercians soon reached a position of unrivaled influence in the Church at large. By 1120 they moved into Italy, by 1123 to Germany, by 1128 to England, by 1132 to Spain, and by 1142 to Ireland, Poland, and Hungary. In time, over six hundred monasteries professed allegiance to Cîteaux.

Their constitution, drawn up by Stephen Harding, insisted on a puritanical simplicity and extreme poverty, while it struck a balance between the extreme centralization of Cluny and the local autonomy of the traditional Benedictines. Each monastery with its abbot was under the immediate supervision of its parent or founding monastery, while it in turn exercised the same jurisdiction over the monasteries it founded. A certain democratic character was provided by the yearly chapters or assemblies, which gathered the abbots and representatives of all the houses; they had the right to depose the abbot of Cîteaux and thus were able to keep in check any autocratic tendency on the part of the head abbot.

The Cistercian experiment also influenced a movement of reform among the parish clergy in the twelfth century. Most notable of these movements was that of the Premonstratensians, founded by St. Norbert (d. 1134), a friend of Bernard. Borrowing liberally from the Cistercian system while basing themselves on St. Augustine’s rule, they soon spread to almost every country in Europe.

The monastic and ascetic impulse found another type of manifestation in the orders of hermit monks who, departing from the standard Benedictine Rule, chose to live in seclusion, with only a minimal amount of community life. St. Romuald (d. 1027), for instance, took up his abode on a desolate mountain at Camaldoli in Italy with a few brethren and spent the time in silent prayer and meditation while living in extreme poverty. This developed into the Camaldolese order, which received papal approval in 1072. The same ideal of complete isolation from the world and absolute poverty was embraced by the founder of the Carthusians, Bruno, a native of Cologne who in 1084 settled in the rugged mountain wilderness of La Chartreuse near Grenoble, France. The Carthusians pushed austerity to the very limits of human endurance, with long fasts and a diet almost restricted to vegetables. Their growth was accordingly slow, but by the fifteenth century they numbered some 150 monasteries. Down to our times they have persevered in fidelity to their original ideal without ever needing a reform, a unique case in the history of religious orders.

The ideal of the monastic orders was complete withdrawal from the world. A new type of religious order, however, arose in the thirteenth century whose aim was to pursue the monastic ideals of renunciation, poverty, and self-sacrifice while staying in the world in order to convert it by example and preaching. These were called friars, from the Latin word fratres, meaning brothers. They were also called the mendicant orders because of their practice of begging alms to support themselves. They were represented mainly by the Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites, and Augustinians. They were, in part, an instinctive response to new social conditions caused by the rise of towns, the revival of commerce, and the growth of population. The shift of population from the countryside to the towns posed a big problem for the Church, whose venerable structures were geared to the old rural, feudal society. It stood in danger of losing touch with the masses who had moved away from the rural parishes and who now lived in the slums that clustered outside the walls of the medieval towns. The mendicant orders proved a godsend in the new urban apostolate.

Their origin may be traced to Francis of Assisi, born in 1181 or 1182, the son of a rich cloth merchant; he was a generous, poetic, high-spirited youth who dreamed of performing daring deeds of chivalry. But after a brief disillusioning career as a soldier, he found himself irresistibly drawn to the Gospel of Jesus Christ and decided to surrender completely to the Lord. He took the words of Jesus literally, and stripping himself of all his possessions, set out barefoot and penniless to preach repentance and a simple message of trust in God and joy in the sheer wonder of God’s goodness. The crowds who listened to Francis grew, and a circle of disciples formed around him. He drew up a simple rule for these “brothers” and took it to Pope Innocent III, who reluctantly gave it verbal sanction. The new order of Friars Minor, as they were now called, continued to multiply and soon spread across Europe.

Confirmation of the Rule of St. Francis. Fresco from The Life of St. Francis. Giotto di Bondone (1266–1336). San Francesco, Assisi, Italy. © Scala/Art Resource, New York.

The simple rule drawn up by Francis contained hardly more than a few of his favorite quotations from the Gospel about love and poverty. Sober spirits, however, realized that a more down-to-earth, businesslike constitution was needed if the order were to survive. Pope Honorius (d. 1227) concurred, and Cardinal Ugolino—who realized the great potential of the movement— helped to draw up a rule that provided a more realistic and orderly government for the thousands of men now involved. But Francis looked on with increasing anguish at what he saw as a harsh and legalistic metamorphosis of his life’s dream. In his Testament, written shortly before his death in 1226, he uttered a wistful protest and tried to call the order back to his lovely Lady Poverty. But after his death the Testament was invalidated and the friars were enabled by legal fictions to possess land and goods. However, a permanent group of dissenters—the Spirituals—persevered in demanding a return to the ideals of Francis and engaged in intense and often ugly controversy with the Conventuals—the party who believed in adjusting the ideal to new conditions.

The other great order of friars, the Dominicans, was founded by Dominic de Guzman (d. 1221), the son of a Castilian noble, in connection with his efforts to convert the Albigensian heretics. Through his friendship with Cardinal Ugolino, he was able to meet Francis and was much impressed by his commitment to poverty. He introduced the idea into the rule for his new order, which he had based mainly on the old Rule of St. Augustine. Unlike Francis, however, Dominic stressed the need for intellectual training to ensure the success of his monks’ preaching. And to this day both orders still retain something of their founders’ spirit: The Dominicans tend to be scholarly, orthodox preachers and writers, while Franciscans will more likely be activists, perhaps even radicals, with a touch of Francis’s merriment.

Together with the less numerous Carmelites and Augustinians, also stemming from this period, these mendicant orders were directly subject to the Pope and proved to be his most effective auxiliaries in tackling the new urban apostolate of the thirteenth century. They supplied most of the Church’s leaders of thought and learning in the Middle Ages; they were its most effective preachers; they excelled as confessors and were the ones chiefly responsible for making the confessional an important part of Catholic piety; they were as well the outstanding missionaries to foreign lands.

The Story of San Domenico di Guzman: The Burning of the Books. Pedro Berruguete (1450–1504). Museo del Prado, Madrid. © Scala/Art Resource, New York.

Bishops, priests, monks, friars, nuns, they were by and large the most educated, the most cultivated, and the most respected members of medieval society during the period of the Church’s ascendancy, and they constituted a much larger percentage of the population than they do today. Their large number enabled the Church to dedicate itself to a wide range of social services, constituting a kind of Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The Church’s care for the unfortunates was concentrated in its hospitals, which at that time were not restricted to care for the sick but ministered to all kinds of needy persons. As such it was the descendant of the hospitium of the fifth-century bishop, who was required by Canon Law to spend a certain portion of diocesan revenue on the poor—a stipulation he carried out largely by endowing a hospitium or home for the poor. The medieval bishop carried on this tradition. At his consecration he was asked whether he would show kindness to the poor, to strangers, and to all in need. This duty he fulfilled by founding and supporting hospitals—not only near his cathedral but also in other towns throughout his diocese. In the fourteenth century, records show that there were eight hospitals in Canterbury, seventeen in London, and eighteen in York, offering food and lodging for the poor. Some hospitals specialized: They might be dedicated, for instance, to the relief of Jews who after their conversion could no longer earn a living by usury; or they took care of the insane (these date only from the fourteenth century) or lepers. It was only with the beginning of the Black Death (c. 1350) that the ordinary hospital out of necessity began to devote itself mainly to the sick.

In harmony with the Church’s actual ascendancy over society, its theologians and philosophers developed a social theory that envisaged the whole social order as an organic hierarchy whereby all of man’s secular activities were ordained to his religious and supernatural goals as means to ends. Each person was assigned by mysterious destiny to a higher or lower place, and each class contributed to the functioning of the whole body. This theory left little room for ideas of change or social reform; the social condition was simply a given. The task of each person was to live up to the calling that God had given him and to remain in the station in life to which he had been born. Social well-being depended on each class performing the functions and enjoying the rights proportioned to it. All the ugly and discordant features of social relationships—the violence, inequities, war, poverty, serfdom, and misery—were regarded as the result of sin and hence a permanent part of man’s pilgrimage here on earth. The only thing the Christian could do about them was alleviate as best he could the suffering of the individuals.

Within this limited framework the Church’s great theologians worked out an ethical system to provide answers for every conceivable moral question. In so doing they based themselves on the Scriptures, on Natural Law (defined as the dictates of human reason insofar as it prescribes actions appropriate to the purpose of each human power or faculty), and on the divine authority of the Church, especially as reflected in the dictates of the Pope.

The medieval theologians even dared to assert that man’s economic activities were subject to moral law. In fact, in the medieval view, the businessman was presumed guilty until proven innocent, since his pursuit of profit for profit’s sake was regarded with great suspicion by Churchmen, who saw it as simple avarice—the most dangerous of all sins. Hence the Church strove valiantly to subject even the economic appetite to its laws. Its ban on usury (defined as taking interest merely for the act of lending) was constantly reiterated, with great emphasis. The Council of Lyons (1274) supplemented the basic prohibition by rules that virtually made the moneylender an outlaw. The Council of Vienne (1312) went even further, by ordering the repeal of all civil law that sanctioned usury. But as Richard Tawney has pointed out, the main point and the one that intrigues many today who are distressed by the economic egotism fostered by capitalism was “the insistence of medieval thinkers that society is a spiritual organism, not an economic machine, and that economic activity, which is one subordinate element within a vast and complex unity, requires to be controlled and repressed by reference to the moral ends for which it supplies the material means.”57

The Church claimed marriage, the family, and all that pertained to it as its very special province. It upheld the unity and indissolubility of marriage and tried to bring some order into the realm of sex. It continued to condemn abortion and infanticide as heinous crimes and severely punished those guilty. It insisted on the human rights and dignity of women, although unfortunately its celibate clergy often lapsed into an almost hysterical disdain for everything feminine.

A Church that aspires to completely dominate a whole culture must know how to compromise with the radical demands of the Gospel. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in the question of war. In comparison with the Eastern Christians, whose stand against war was generally consistent, Western Christendom appears much less enlightened. The barbarian invasions and the conditions of feudal society made war a constant fact of life; ecclesiastics tried to channel this bellicose energy for the Church’s own purposes. Holy war in the service of the Church was regarded as permissible and even desirable. Popes even led armies into battle and ranked the victims of a holy war as martyrs.

However, a peace movement did begin in France in the tenth century at the Council of Charroux in 989, where the bishops of Aquitaine proposed the Peace of God, outlawing war against the clergy, women, the poor, and the defenseless. A series of Church councils followed in France, which prescribed oaths to be taken by the nobility to limit their war-making propensities. Then Leagues of Peace were organized—the first one by the archbishop of Bourges in 1038—committing the members to take up arms if necessary to suppress those who made war. Supposedly seven hundred clerics alone perished in one such war for peace. A more practical measure was the Truce of God in the eleventh century, a movement inspired by the Church. It prohibited all warfare on holy days and during Lent and Advent and other special feasts. Violation brought with it automatic excommunication.

The Church still taught as late as the eleventh century that it was a grave sin to kill a man in a battle waged for only secular purposes. And even though the Battle of Hastings in 1066 was blessed with papal approval, the victors were given severe penalties for the deaths they had caused. Somewhat later the theologians revived Augustine’s theory of the “just war,” which allowed secular rulers the benefit of the doubt unless they were acting against papal interests. And so actually it became very difficult for Churchmen to declare that any properly authorized war was unjust.

It is in this context that we must try to understand the Crusades, which were such a remarkable expression of the medieval mind. Pope Urban II set them in motion in 1095, and throughout their long history they remained a largely papal enterprise. Urban addressed the Christian knights present at the Council of Clermont that year and summoned them to turn their fighting spirit to a more fruitful purpose by rescuing the Holy Land from the infidel Moslems. Under the hypnotic spell of the Pope’s brilliant oratory and his promise of an eternal reward to those who died in the cause, the knights thundered in reply: “God wills it”; they sewed red crosses on their tunics and immediately laid plans for the expedition.

As with most major movements in history, a complex of motives and circumstances played a part in the genesis of the Crusades. The Normans, Italians, and French had already assumed the offensive against the Moslems and wrested control of the western Mediterranean from them; they were now ready to turn to the East. The reform of the papacy under Hildebrand meant that people now looked to the Pope as head of Christendom and were ready to follow his lead. Stories were also circulating about the harsh treatment of Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem at the hands of the infidel, inflaming Western opinion. The Eastern Emperor, Alexius, appealed to Urban for help in recovering Byzantine territory in Asia Minor from the Turks, while Urban saw a chance to reunite Eastern and Western Christendom under papal headship. Not the least of the factors was the dynamic personality of Urban himself, whose extraordinary energy and organizing ability did much to assure the initial success of the movement.

A medley of motives inspired the rugged knights: love of adventure, devotion to Christ, and lust for land. Under such leaders as Hugh of Vermandois, Raymond of Toulouse, Godfrey of Bouillon, Robert of Flanders, Stephen of Blois, Bohemond of Taranto, and the papal legate, Adhemar of Puy, the crusading armies were assembled in Constantinople by May 1097; they swore an oath of fealty to Emperor Alexius and then captured the Moslem capital of Nicaea. One of the great epics of military history then occurred as the mailed knights and sturdy foot soldiers trekked across Asia Minor fending off attacks by Turkish horsemen though tormented by lack of food and water and the extreme heat. After four months they reached Antioch and laid it under siege. There on June 28, 1098, they won the decisive victory that determined the successful outcome of the First Crusade.

On June 7, 1099, their army of twelve thousand—about half of those who began the march across Asia Minor—arrived at the strongly fortified walls of Jerusalem. At the second attack it fell, and on July 1 the victors poured out their feelings in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and then poured out indiscriminately the blood of the inhabitants—Moslem and Jewish, men, women, and children.

In spite of their oath to Alexius the crusaders formed only a loose confederation, unified only by their undefined allegiance to the Pope and his legate, Adhemar, but torn by personal animosities and rivalries. A heavy blow to even this frail unity occurred when the lovable and tactful Adhemar perished in an epidemic after the victory at Antioch. Disunity continued to characterize the history of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem and its theoretically subject fiefs in Syria—the county of Tripolis, the county of Edessa, and the principality of Antioch. Another serious misfortune was the crusaders’ failure to capture the important cities of Damascus, Emesa, Hamah, and Aleppo. When the Moslems finally united they began a piecemeal reconquest that even the Second Crusade (1147) failed to arrest. The smashing victory of Saladin at Hattin in 1187 and his capture of Jerusalem climaxed the reconquest. Nor could the Third Crusade (1189–92) and all the succeeding ones restore Latin supremacy over the Near East.

There is no doubt, however, that the Crusades contributed much to the developments of the time: the rise of commerce and towns, the growing sense of nationality, the expansion of intellectual horizons, and the increase in the prestige of the papacy. But in none of these instances was the influence decisive. The taste for Eastern spices, silk, and metalware, for instance, was already stimulated by a trade that was growing independently of the Crusades; the crusaders’ effect on the rise of commerce was not as crucial as is sometimes supported. Probably their most important effect was to retard the Turkish advance into the Balkans for three hundred years.

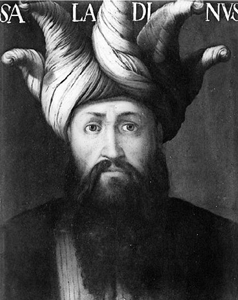

Portrait of Saladin (1138–1193), sultan of Egypt. Anonymous. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. © SEF/Art Resource, New York.

As we can see from this brief survey, the Church’s impact on medieval society was profound. In every department of life one found the Church present. Under the leadership of the Popes, the priests, monks, friars, and nuns who were the spiritual elite of medieval society labored steadily to instill faith in the illiterate masses, to give them at least a glimpse of truth and goodness beyond the grim facts of their narrowly circumscribed lives. But how successful were they? Did the Gospel penetrate beyond the surface of medieval life? Was it distorted in its transmission to the masses? These are questions that nearly transcend the boundaries of historical science. But perhaps some judgment can be made. There is no doubt that the Church made great compromises in adapting the message of its founder to the exigencies of a feudal society. Its barbaric holy wars, its crude anti-Semitism, its sanguinary Inquisitions, and its chase after witches, are enough to show how far compromise could go. But at the same time, the urge to reform was never absent either. There was always a prophetic current critical of the establishment and anxious to lead Church and society to greater fidelity to the demands of the Gospel as they were then understood. One has only to think of such movements as Cluny, the Cistercians, and the Franciscans to appreciate this fact. And one can agree with the conclusion of a recent study by Francis Oakley, “. . . for whatever its barbarisms, its corruptions, its malformations, whatever its evasions and dishonesties, in the medieval church men and women still contrived, it would seem, to encounter the Gospel.”58