Chapter 20

CALVIN MAKES PROTESTANTISM AN INTERNATIONAL MOVEMENT

John Calvin, the architect of international Protestantism, was born at Novon, France, July 10, 1509, the son of a notary, Gérard Cauvin (Calvin is the Latinized form), and his wife, Jeanne Lefranc. With the help of Church benefices, John studied theology in Paris in preparation for the priesthood and then switched to law and classical languages, which he pursued under some of the most famous professors of the day at Orléans and Bourges. Calvin was always quite reticent about the details of his personal history and never spoke much about the spiritual development that led to his conversion to the Protestant cause in 1533 or 1534. However, his Reply to Cardinal Sadoleto (1539) sheds some light on this matter, especially in the passage where he relates the story of a hypothetical conversion to the Protestant faith which is very likely drawn from his own experience. The convert in question attributes his change of religious allegiance to a number of reasons: his failure to find peace of conscience through the medieval system of satisfactions and his soul’s terror in this condition; the comfort brought by the new and very different doctrine of the sufficiency of Christ’s work of satisfaction; the conviction that the aim of the reformers to correct the abuses in the Church was not schismatic in intention; and finally his belief that the papacy was not warranted by Scripture but was a tyranny based on empty claims.80

The Protestant reformer John Calvin (1509–64) as a young man. Flemish School. Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire, Geneva. © Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

At any rate Calvin eagerly devoted himself to his new religion and was soon in the forefront of the Protestant movement in France. To espouse Lutheran ideas at that time under the Catholic King, Francis I, was to invite trouble and it was not long in coming. Calvin found his situation in France untenable, especially after the Affair of the Placards, an episode which occurred in October 1534 when some Protestant enthusiasts papered Paris with posters denouncing the Mass. The authorities took stringent measures against the heretics and the Protestant martyrology began to grow. Unwilling to add his name to the list, Calvin took refuge in Basel.

It was here in 1536 that he published in Latin the first edition of his Institutesof the Christian Religion, a lucid handbook of Protestant doctrine that immediately lifted him to a position of eminence among the leaders of the reform movement. It was a book that continued to grow in size over the years as Calvin translated it into French and repeatedly revised and enlarged it. It is a book that has few rivals in the enormity of its impact on Western history and ecclesiastical and political theory.

Soon afterward, Calvin set out to visit Ferrara, where the seeds of an Italian reform movement were beginning to sprout. After a brief return trip to Paris he set out for Strassburg in June 1536 intending to lead a quiet life of scholarship and writing on behalf of the Protestant cause. But a detour he took by chance through Geneva set his life on an entirely different course. While stopping at Geneva he was induced by the Protestant reformer Guillaume Farel to remain and take part in the struggle to transform Geneva into a vital Protestant community. Farel and his companions had already gained the upper hand by their spirited preaching and their ability to vanquish their Catholic opponents in public debate. The Catholic bishop had been driven out, the Mass suspended, and a set of regulations adopted which imposed the reform on the citizenry. But opposition was still strong and Farel saw in Calvin the man of the hour and begged him to remain and complete the work.

After some hesitation Calvin accepted Farel’s offer and set about the task of creating in his words a “well ordered and regulated” Church.81 He drew up a confession of faith to be signed by each citizen to show whether one belonged to the kingdom of the Pope or the kingdom of Jesus Christ. Rules were drawn up for the proper and frequent celebration of the Lord’s Supper and a system of discipline enacted that governed the behavior of the Genevans down to rather slight details. However, when Calvin and his colleagues demanded the right of the Church to enforce its discipline by the penalty of excommunication, the magistrates demurred, seeing in this a move to make the Church an independent power. Other issues caused tension, and opposition to the reformers reached a high pitch when a dispute arose over certain liturgical practices (such as use of the baptismal font) which the Genevans had resumed under pressure from neighboring Bern. Calvin saw this intervention by Bern as a violation of the autonomy of the Genevan Church and stoutly resisted the move. In consequence, Calvin, Farel, and their associates were banished from the town.

From 1538 to 1541 Calvin resided in Strassburg, which he visited at the invitation of Martin Bucer, an ex-Dominican Lutheran preacher who had considerable influence on Calvin’s subsequent theological development. It was under Bucer’s influence that Calvin shaped the form of public worship that was to become the standard for Calvinist churches. Opposed as he was to the heavy emphasis on ceremonies in the Roman communion, Calvin devised an extremely plain and simple rite that still preserved, however, the outline of the Roman Mass. While in Strassburg he also revised and published a new edition of his Institutes, began his outstanding series of Biblical Commentaries which eventually included all the writings of the New and most of those in the Old Testament. He also attended the colloquies at Worms in 1540 and Regensburg in 1541, convened by the Emperor Charles V, in an effort to heal the religious schism, although Calvin himself didn’t think they had much chance of success. In 1540 he married Idelette of Buren, the widow of one of his converts. Their only child, a boy, died soon after birth.

In the meantime Geneva remained in turmoil, still divided over the issues that had forced Calvin out. His supporters finally gained the ascendancy and the city decided to invite Calvin to return. With great misgivings, but moved by a sense of divine vocation, Calvin re-entered the troubled city on September 13, 1541. He immediately set to work to turn the town of thirteen thousand inhabitants into a truly reformed Church and properly disciplined community. The blueprint for such a project being already firmly worked out in his mind, he was able within a few months to present his Ecclesiastical Ordinancesto the General Council of Geneva which they officially adopted on Sunday, November 20, with modifications to safeguard their own civil jurisdiction. Together with the Institutes this design for an ideal Christian community was Calvin’s lasting contribution to Christianity, for his constitution became the organizational basis for all the Churches that accepted Calvinist doctrine. In drawing it up, Calvin aimed to reproduce as far as possible the organization of the Church which he found in the New Testament. Four offices were established: pastors, teachers, elders, and deacons. Strict discipline was the key to success in Calvin’s mind and he entrusted the task of disciplining the community to a body called the Consistory made up of the ministers and elders. They were charged with closely supervising the behavior of their fellow citizens, who, if necessary, could be excommunicated by the civil authorities.

Legislation closely regulating private behavior was not an unusual feature of medieval town life. What made Geneva unique at this point in time was the consistency and severity with which the laws were enforced. The records of the Consistory show that people were haled before the elders and magistrates for even trivial offenses: laughing during a sermon, singing songs defamatory of Calvin, dancing, or frequenting a fortuneteller. Geneva’s public life gradually began to change under this strict regimen. Prostitution, a notorious feature of pre-Calvin Geneva, was stamped out, the theater was closed, and the death penalty was prescribed for adultery and was actually imposed in several cases.

Calvin is sometimes accused of ruling Geneva as a dictator. A misnomer, indeed, for Calvin held no political office and used no other means than sheer moral power to impose his idea of the good life on Geneva. Moreover, he was often in danger of losing his sway over the city, as he had numerous enemies who hated his unbending regime or disagreed with his interpretation of the Word of God. Calvin never shrank from conflict and, in spite of the shifting tides of public opinion that sometimes ran strongly against him, he always managed to defeat his foes and restore his dominance. Crossing swords with the pope of Geneva was a dangerous pastime and the vanquished often paid for it dearly. Jacques Gruet, for example, was one of the so-called Libertines who bitterly resented the life style imposed by Calvin. Gruet was arrested, tortured in the manner of his age, and, when evidence was found convicting him of blasphemy, beheaded. But Calvin’s most celebrated victim was Michael Servetus, the Spanish physician and anti-Trinitarian who, while in flight from the Catholic Inquisition, mistakenly stopped at Geneva, where at the behest of Calvin he was arrested and after trial burned at the stake for heresy.

The crowning achievement of Calvin was the establishment in 1559 of the Geneva Academy, designed primarily to give a complete education to candidates for the ministry. It became a powerful center for the spread of Calvinism, as its students came from many lands to learn the theology of the Reformed Church at its source. Calvin suffered much from illness in his last years but remained at his post until the end came in 1564. His corpse, as one eyewitness recalled, was “followed by almost the whole city, not without many tears.”82

As the supreme theological genius of Protestantism, Calvin laid the groundwork for subsequent theological developments within most Protestant non-Lutheran Churches. Calvin thought of himself as the successor of Luther and indeed stood in complete agreement with Luther on the basic principles of Protestantism: Scripture alone as the sole source of saving truth, salvation by faith alone, the priesthood of all believers. Indeed, it can be said that “the central teaching of Luther on justification of faith and regeneration by faith was preserved more faithfully and expressed more forcefully by Calvin than by any other dogmatician of the Reform.”83 Nevertheless, as his thought matured he found cause to differ sharply with Luther on a number of important points—having to do with the Lord’s Supper, the Canon of Scripture, predestination, the doctrine of the Church, Christology, and the sacraments.

Calvin is sometimes thought of as a rigorously systematic thinker who carried logical consistency to extremes in elaborating his synthesis of Christian doctrine. In fact, Calvin considered himself, and should be considered, as primarily a masterful expositor of the Scriptures, a biblical theologian who strove to transmit accurately and completely the whole message he found in Scripture and who laid great stress indeed on the point that Scripture contained all that was necessary for salvation. He organized his material around the grand themes that give unity to the Scriptures without trying to resolve the paradoxes and logical tensions to be found there.

Although one cannot single out any one doctrine as the foundation of his thought, a good starting point is his insistence on the absolute sovereignty of God. One of the most serious charges he leveled at the Roman Church was that it domesticated God. The God of the Roman Church in Calvin’s eyes was “a God who could be summoned at clerical command, localized and dismissed by the chemistry of stomach acids.”84 In protest Calvin often insisted on God’s absolute transcendence and total otherness, on his mysterious, incomprehensible essence, his unfathomable purpose, and his inscrutable decrees. He was a hidden God. Saving knowledge of him could only be found in Scripture and this only on condition that we read it with reverence, faith, and love. God reveals himself to us in Scripture only through Jesus Christ, who is the core and the whole content of its meaning.

How do we know that Scripture is true? For Calvin, it is only through the interior witness of the Holy Spirit that we can recognize in Scripture the Word of God speaking to us. Scripture in turn testifies to the all-embracing sovereignty of God and reveals Him as the Ruler who governs all things by his providence. It is in this context that Calvin formulated his much attacked doctrine of predestination according to which by God’s eternal decree some are ordained infallibly to eternal life and others infallibly to eternal punishment. This was the Achilles’ heel of his theology and the target of all his opponents. While it is true that Calvin here goes beyond the plain demands of Scripture, we must remember that he felt obliged to assert predestination in order to safeguard one of his main concerns, namely, the absolute gratuitousness of God’s saving grace—in no way dependent on our merits or works.

In his doctrine of original sin, as often elsewhere, Calvin follows Augustine closely. Calvin teaches that through original sin man became utterly depraved and in his relation to God capable only of sinning. Man is saved from this plight by faith in Christ the sole mediator. But man does not initiate this movement of faith; rather, it is the principal work of the Holy Spirit. Faith, he says in his Institutes, “is a firm and sure knowledge of the divine favor toward us, founded on the truth of a free promise in Christ, and revealed to our minds, and sealed on our hearts by the Holy Spirit.”85 Faith unites us with Christ in a personal relationship of faith. But this faith in itself does not have any worth. It is only the instrument whereby we obtain freely the righteousness of Christ—which remains Christ’s righteousness and is only imputed to us.

Unlike Luther, Calvin emphasized not only justification but also our sanctification. This does not mean that we grow intrinsically in righteousness but only that we become more and more aware of our own impotence and sinfulness as we are more deeply grafted into Christ, who accomplishes for us what we should have done ourselves. Even after our justification, our works are still contaminated by sin, but God nevertheless holds them acceptable. He not only justifies the sinner; he also justifies the justified in a process referred to as double justification. In this context also, Calvin explains regeneration. While remaining sinners, we nevertheless advance in holiness insofar as we are united with Christ. This grace that Christ gives us is irresistible and manifests itself especially in our readiness to deny ourselves and live in view of the life to come.

In his understanding of Christ, Calvin follows tradition very closely, affirming the dogmas of the ancient councils as to Christ’s consubstantiality with the Father and the Holy Spirit and the personal unity of Christ’s two natures.

When we come to Calvin’s doctrine of the Church we find that Calvin stressed the importance of the Church as a divinely willed institution, as the means intended by God to help weak and infirm man along the path to salvation. The supreme Church for Calvin is the invisible one made up of the totality of the elect, but there was also the visible Church formed by the gathering of believers into one parish. For Calvin, who here follows Luther closely, the marks of a true Church are simple and evident: the Church exists wherever the Word of God is preached and the sacraments administered according to Christ’s institution. Rejected was the Roman view that the Church existed only where bishop succeeded bishop. For him that was much too organizational a concept, too mechanistic, too concerned with structural continuity and not concerned enough with continuity and purity of doctrine. It is Jesus, Calvin holds, who calls the Church into being by his Word and his sacraments. And for Calvin there were only two sacraments attested to in Scripture: Baptism and the Eucharist.

One of the abuses Calvin saw rampant in the Roman Church was a quasi-magical and mechanistic use of the sacraments which he blamed on the official Roman doctrine that the sacraments conferred grace of themselves (ex opere operato). He therefore laid stress on the importance of the faith of the recipient and on the role of the sacraments as part of a personal dialogue between the believer and God. And he held that the administration of the sacrament must always be accompanied by a preaching and proclaiming of the Word. “Nothing . . . can be more preposterous than to convert the Supper into a dumb action. This is done under the tyranny of the Pope.”86

In his doctrine of the Eucharist, Calvin followed closely the theology of his friend Martin Bucer, who tried to mediate the dispute between Zwingli and Luther mentioned above.87 Luther, as we explained, insisted on the objective real presence of Christ’s body in the bread and wine, while Zwingli upheld only a memorial presence. Bucer on the one hand agreed with Zwingli in saying that the divine gift was not given in or under the forms of bread and wine, but on the other hand Bucer agreed with Luther as to a true communication of the Lord’s humanity in the sacrament. To harmonize the two views Bucer favored the statement that the divine gift was given not in or under but with the bread and wine: When the bread was eaten the divine gift passed into the faithful soul. Bucer’s doctrine gradually established itself as the classical formulary of non-Lutheran Protestantism. Calvin took it up and stamped it with his own characteristic clarity and cogency. According to Calvin the bread and wine are as instruments by which Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself distributes to us his body and blood. The Eucharist was not a mere psychological aid to grasping spiritual reality but the means by which God accomplishes his promise. The presence of Christ in the Eucharist was an objectively real presence.

CALVINISM CENTERED I N Geneva became the great engine of Protestant expansion in Europe. Only Germany and Scandinavia preferred Lutheranism. Most of the other countries that turned Protestant accepted Calvinism or something close to it. Its progress in Switzerland was greatly helped by the formula of faith signed by Calvin and Zwingli’s successor, Heinrich Bullinger, in 1549. Very influential also was the Second Helvetic Confession, a very Calvinistic document, which was signed by all the Swiss cantons except Basel and Neuchâtel and enjoyed wide popularity.

While no German city became Calvinist during Calvin’s lifetime, the doctrines of the Genevan reformer found a favorable climate in the Palatinate under the Elector Frederick III (1515–76). This sincere and intelligent religious prince invited two outstanding Calvinist scholars, Zacharias Ursinus and Caspar Olevianus, to his University of Heidelberg and they collaborated in producing the Heidelberg Catechism (1563), which became the creed of the Reformed churches in Germany as well as those in Poland, Bohemia, Hungary, and Moravia. In addition to the Palatinate, the most important of the other German states which accepted Calvinist doctrine were Bremen, Anhalt, the main part of Hesse, and finally Brandenburg, a unique example where the Calvinist sympathies of the Electors secured for Calvinists a legal position although Lutherans remained in the majority.

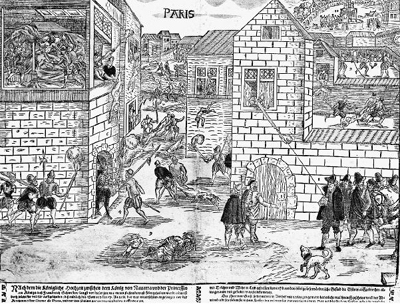

In Huguenot France, in Holland, and in Scotland the Protestant movement assumed the form of Calvinism between 1559 and 1567. France became a veritable battleground for a series of wars between Calvinist Huguenots and Catholics that devastated the country. The Huguenots suffered a calamitous blow in the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre when at the command of the Queen Mother, Catherine de Medici, thousands of them were caught by surprise and butchered. But the survivors managed to regroup and, under their leader, Henry of Navarre, continued the struggle. Henry, however, turned Catholic in order to unify the country under his rule, but his Edict of Nantes (1598) guaranteed liberty of conscience for the Huguenots.

At the time of the death of Calvin in 1564 Calvinism had already made significant progress in the seventeen provinces of the Netherlands (today mainly Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg). They were ruled by the Spanish monarch Philip II who alienated the populace by his arbitrary taxation, his use of Spanish troops, and his repressive ecclesiastical policies. When war with the Spanish broke out, the courage and boldness of the Calvinists contributed greatly to the dynamism of the anti-Spanish movement and the leader of the rebels, William, the Prince of Orange, himself became a Calvinist. William was assassinated in 1584 but the victory of his son Maurice, who drove out the Spaniards, led to the establishment of the Calvinist Dutch Republic in the northern Netherlands, which became one of the most vibrant and flourishing centers of Calvinism.

Nowhere did Calvinism succeed as completely as it did in Scotland. Its implantation there was due mainly to John Knox, who learned his Calvinism from the lips of the master himself at Geneva. Knox was a Scottish priest who went over to the cause of the Reformation early in his career. He joined a group of rebels who had occupied the castle of St. Andrews after assassinating Cardinal Beaton, the primate of Scotland. Unable to withstand a battery of French cannon, the rebels were taken prisoner and Knox spent nineteen months in the French galleys. After other vicissitudes he ended up in Geneva with Calvin. Mary Tudor’s death in 1559 enabled Knox and the other Calvinist refugees to return home. The withdrawal of both English and French troops by the treaty of Edinburgh, July 6, 1560, and the death of the regent, Mary of Guise, allowed Knox and his band of reformers to steer Parliament toward reformation ideas. The First Scottish Confession, a faithful reproduction of the basic doctrines of Calvin, was read in Parliament and passed without delay August 17, 1560. It remained the confessional standard until superseded by the Westminster Confession in 1647. A Calvinist form of the liturgy was adopted in 1564. When the Catholic Queen Mary Stuart ascended the throne of Scotland in 1561, she found the new religion already entrenched. She was undone by her marriage to the Earl of Bothwell after the murder of her husband Lord Darnley. With Mary imprisoned in an English castle, Knox could die in 1572 with the comfort of knowing that the reformed church was now deeply rooted in the life of the people. After his death the Scottish Church remained doggedly attached to its presbyterian form of Calvinism in spite of the energetic attempts of its Stuart Kings to make the Kirk episcopal.

The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. Sixteenth-century German woodcut. Bibliothèque de l’Histoire du Protestantisme, Paris. © Giraudon/Art Resource, New York.

The Calvinists also played an important, if belated, role in the English Reformation, but they never succeeded in dominating the English Church the way they did the Scottish and Dutch Churches. We must keep in mind that whereas in Holland and Scotland the Reformation began as a religious movement led by Calvinists, the Reformation in England began as a political affair engineered by the King himself, Henry VIII. Henry, in fact, stoutly opposed the Reformation ideas and even wrote a treatise against Luther, The De fense of the Seven Sacraments, which won for him from Pope Leo X on October 11, 1521, the title of “Defender of the Faith.”

But Henry’s relations with the papacy deteriorated rapidly when the issue of his divorce surfaced in 1527. He wanted the Pope to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon so that he could marry the current object of his passion, Anne Boleyn, who he hoped might also provide him with the male heir that he so desperately wanted. The Pope, Clement VII, found himself in a terrible predicament. On the one hand, Henry threatened to withdraw England from its papal allegiance if not satisfied, and on the other, Catherine produced good evidence to show that her marriage with Henry was valid. Moreover, the Pope was under considerable pressure to refuse the divorce from Catherine’s uncle, the powerful Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Clement vacillated and finally revoked the case to Rome in July 1529.

Henry immediately summoned Parliament and his clever lieutenant Thomas Cromwell steered it through a series of Acts that gradually detached England from the Pope’s jurisdiction and subjected the English Church to the King, who in 1534 was declared to be the supreme head of the Church of England. Among the few men of prominence, clergy or lay, who refused to swear to the royal supremacy were John Fisher, the bishop of Rochester, and Thomas More, the ex-Chancellor, both of whom were beheaded in 1535.

Henry meanwhile obtained his divorce from the new archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, who crowned Anne with great pomp in the abbey church at Westminster on June 1, 1533.

Next to his rejection of papal jurisdiction, the most revolutionary act of Henry was his dissolution of the monasteries from 1535 to 1540. Some nine thousand monks and nuns were turned out—some willingly—and an enormous amount of wealth changed hands. While no longer the powerful spiritual force and centers of learning they were in the early Middle Ages, the monasteries were an important part of traditional church life and their destruction was an important factor in the gradual triumph of reformation ideas in England. The spread of these ideas occurred in spite of Henry, who though defiant of the Pope remained deeply devoted to traditional Catholicism and was determined to maintain its substance. It is true that under the pressure of political necessity Henry allowed the publication of the ambiguous Ten Articles(1536) and he also approved of the Act that set up the English Bible in all the churches. But his Six Articles (1539) reaffirmed Catholic doctrine and imposed savage penalties for denial of transubstantiation, private Masses, private confession, or the need for clerical celibacy.

It was only with the death of Henry in 1547 and the advent of young Edward VI that the Protestant party in England took charge and Calvinist influence began to make itself felt. The leader of the Protestants was Thomas Cranmer, who in spite of his Protestant tendencies had managed to escape Henry’s wrath. The revision of the English Church’s liturgy through The Book of Common Prayer (1549) was largely his work and it is justly celebrated as a liturgical masterpiece. It follows the basic outline of the medieval Mass but at crucial points inculcates Protestant doctrines. However, Cranmer himself soon found it too conservative, influenced as he now was by his personal contacts with Martin Bucer, whom he had invited to England. He helped to secure its revision and the Second Book of Common Prayer (1552) reflects his efforts to simplify the English liturgy along Calvinist lines and move its Eucharistic formulas closer to the doctrine of the Swiss reformers.

The work of the Protestant Reformers in England was interrupted by Mary Tudor, who succeeded Edward in 1553 and was absolutely devoted to restoring papal authority in England. To that end she engaged in a full-scale persecution of dissenting Protestants and sent Cranmer himself to the stake. She only succeeded, however, in moving the English people closer to a genuine acceptance of Protestantism.

With the arrival of Anne Boleyn’s daughter, Elizabeth, as Queen in 1558, the Calvinists strove in earnest to take over the English Reformation and shape it along their lines. Nicknamed “Puritans” they sought to cleanse the English Church of everything they considered superstitious, idolatrous, and popish. The Book of Common Prayer, revised again in 1559, especially bothered them for though it called the altar a table and no longer referred to the Lord’s Supper as a sacrifice, it still retained much they thought unwarranted by Scripture, such as vestments, the sign of the cross, kneeling at communion and formal prayer. Their other main target was the office of bishop, which they wanted to replace with a presbyterian form of church government such as prevailed in Scotland. Elizabeth turned a deaf ear to them, however, for she was committed to a policy of expediency in religious matters and wanted a national religion that would blend the Catholic, Lutheran, and Calvinist elements in a way that would unify all Englishmen in one Church. Although the Puritans had considerable influence on the formulation of the Thirty-Nine Articles (1563) they never succeeded in establishing a Calvinist system in England but remained under Elizabeth an important wing of the English Church fiercely hostile to their adversaries the Episcopalians, who still believed in bishops.

Queen Elizabeth I of England, the Siève portrait, c. 1575. Federico Zuccaro (1543–1609). Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena. © Scala/Art Resource, New York.

Under the Stuart Kings of England in the seventeenth century the struggle between Puritans and Episcopalians became extremely bitter. Both James I (1603–25) and Charles I (1625–49) steadily discouraged the Puritan and encouraged the anti-Puritan party within the Church of England. During Charles’s reign the archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud (d. 1645), undertook an aggressive campaign for a full revival of the Catholic tradition in the Church and tried to force the Puritans to conform by the use of severe penalties. This led to the great Puritan migration to the New World. Some twenty thousand Puritans left England in the 1630s to join others already in New England in founding holy commonwealths based on Calvinist doctrine. Under the leadership of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Calvinism flourished and greatly influenced the shaping of the new nation.

CALVINISM HAS NOT been immune to the shocks that all systems suffer as they pass through the crucible of history. Its adherents eventually split into a host of separate churches that often bickered with each other over trivial issues. Some of its key doctrines had to be abandoned as knowledge advanced and no one today accepts it as a complete system. But few would deny that Calvin’s contribution to Christian life and thought has been of the highest order. And we can still meditate with profit on what he has to tell us about the transcendence and sovereignty of God, the depths of man’s depravity, the absolute freedom of grace, and our call to a deep interior response of faith.