Chapter 21

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH RECOVERS ITS SPIRITUAL ÉLAN

The Catholic Church’s history from the very beginning has been punctuated with terrible crises: the persecutions by the Roman Empire, the rise of Arianism, the barbarian invasions, the struggle over lay investiture, the Schism of the East, the Great Schism. But it would hardly be an exaggeration to say that Luther’s revolt was the most devastating of them all. Never before was there so widespread and sudden a desertion of its altars, and never before had so many priests and nuns abandoned their cloisters, almost overnight. When it was all over, half of Europe was lost to the Roman obedience, and the unity of Christendom was but a fading memory.

However, there is for Catholics a brighter side. An interior and spiritual renewal occurred within the Catholic Church during the sixteenth century that made it once more a vital and sturdy spiritual household—worthy of a Gregory VII or an Innocent III. There is much evidence, as we have seen, that this spiritual and interior reform antedated Luther and hence cannot be explained as a mere defensive reaction or Counter Reformation. On the other hand, there is no doubt that the Lutheran Reformation intensified the feeling of urgency—carrying forward the Catholic effort toward a deepened spirituality.

THE ORIGINS OF this renewal can be traced to certain initiatives taken in Italy and Spain. We have already mentioned the Spanish reform centered around Ximenes de Cisneros. The usually accepted starting point in Italy was the founding of the Oratory of Divine Love in Genoa in 1497; it was dedicated to personal spiritual renewal through the practice of regular religious devotions and the works of mercy. Its membership was half lay and half clerical. Similar groups soon spread throughout Italy, and around 1514 one even took root in the Roman Curia. Although it was predominantly a lay affair, it included in its membership some of the outstanding prelates of the day and numbered among its leaders a Venetian, Gaspar Contarini, who has been called “the heart and soul” of the reform movement in the Curia.88

A direct offspring of the Oratory was a new type of religious order, the Theatines, founded by members of the Roman branch of the Oratory, Gaetano de Thiene (d. 1547) and Gian Carafa (d. 1559), later Pope Paul IV. They were convinced that reform had to begin with the parish clergy, and so their object was to organize secular priests into communities based on the common observance of poverty, chastity, and obedience and to raise the level of clerical spirituality. The order became a seminary of bishops, a byword for austerity, and a continual force for the reform of the Italian clergy.

The idea caught on, and a number of similar orders sprang up—the Somaschi, founded in 1532 by Jerome Aemiliani and centered in Venice; the Barnabites in 1530; and the most successful of all, the Jesuits, who began as a small band of men personally recruited by Ignatius Loyola in Paris in 1534. They moved shortly afterward to Italy and Rome, where they received papal approbation in 1540. Another sign of the forces of renewal working in the Church in Italy were the Capuchins, founded in 1528 as an offshoot of the Franciscans; they wanted to restore the Franciscan Order to its primitive ideals. They multiplied rapidly and soon became a familiar sight in their coarse garment with its large square hood. They rivaled the Jesuits in numbers and in their influence on the course of the Catholic Reformation.

Another great influence on the spiritual revival of the Italian Church was Gian Matteo Giberti, a member of the Oratory of Divine Love and bishop of Verona from 1524 to 1543. The terrible sack of Rome in 1527 by invading German troops appeared as a divine warning to him, and he plunged into the work of pastoral reform in his diocese of Verona, which up to this point he had neglected. In an age when absentee bishops proliferated, Giberti showed the difference an energetic resident bishop could make for the life of the Church. Carrying on a ceaseless round of searching visitations, he left no aspect of Church life untouched: Liturgy, parochial work, preaching, monastic communities, the social apostolate—all were the object of his wise reform decrees. Many of them were later incorporated verbatim into the general legislation of the Council of Trent. Even more important than Giberti’s legislation was the example he gave—which showed the bishops of his day what could be accomplished by a full-time bishop resident in his diocese and wholly intent on reform.

But the problems facing the Church—doctrinal confusion, fiscal abuses, widespread ignorance, and organizational breakdown—were on too grand a scale to be tackled merely at the local level. And it is one of the great tragedies of Reformation history that it took so long to call a general council of the Church. It required no less than twenty-eight years after Luther first raised his cry! Numerous obstacles stood in the way: papal fears of a revival of conciliarism, opposition from antireform members of the Curia, the hostility of the German princes, and the political rivalry of France and Spain. It is to the enormous credit of Pope Paul III (d. 1549) that he was able to surmount them all by his dogged perseverance and finally convoke the council that opened on December 13, 1545, in the northern Italian city of Trent, with some thirty bishops in attendance.

Pope Paul III Farnese (1534–49). Titian (1488–1576). Museo Nazionale de Capodimonte, Naples. © Scala/Art Resource, New York.

It took eighteen years for the council to complete its work, from 1545 to 1563, although it was in actual session for only a little more than three of these years. The first session came to an end in 1547, when Charles V returned to his policy of seeking reunion by dialogue between Catholics and Protestants in the hopes of finding an acceptable compromise. The long interlude of ten years between the second session (1551–52) and the third (1562–63) was due to a variety of causes: A new generation of political leaders appeared who were less concerned about religious problems, while Pope Paul IV, a vigorous, reform-minded Pope who reigned from 1555 to 1559, preferred direct papal action to a council. But his successor, Pius IV (d. 1565), reverted to the previous papal policy, and by dint of much diplomacy and tenacity finally succeeded in reassembling the Council for its third and last session.

The Council addressed itself to the problems of doctrinal confusion and organizational breakdown. In a series of important decrees—answering Luther’s resounding denials with ringing affirmations—it drew a sharp line of demarcation between the Catholic and the Protestant teaching. Scripture and tradition were both declared necessary in determining the faith of the Church. On the issue of justification, which Luther considered the key to the whole dispute, Trent refused any compromise. The bishops denied man’s total corruption by original sin and asserted that our justification was not actualized by faith alone but also by hope and charity as well. Moreover, charity had to be expressed in good works carried out by the co-operation of the human will with God’s grace. Against Luther they also asserted the dogmas of the divine validity of the seven sacraments, the hierarchical nature of the Church, the divine institution of the priesthood, the traditional teaching on transubstantiation, and the sacrificial character of the Mass.

The doctrinal definitions they laid down were quite narrow. Not all Catholics agreed with them, but there was no longer any question about the limits of orthodoxy on important issues. The trend as a whole at the council was extremely conservative; the liberals were not given much of a hearing. Thus in requiring seminaries for the future training of priests, the bishops made sure that the training given would be highly traditional, and they paid little heed to the progress in biblical studies made by the humanists.

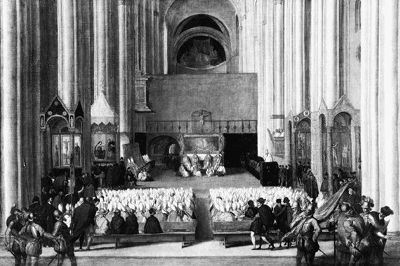

Council of Trent (1545–63). Anonymous, Italian School, sixteenth century. Louvre, Paris. © Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, New York.

In the same way they reaffirmed tradition as regards the structure of the Church. Their most important measure, no doubt, was acknowledging papal supremacy and so laying to rest the ghost of Constance. And by submitting its decrees to the Pope for confirmation and entrusting to him the task of carrying out its incomplete work, they further strengthened the hold of the Pope over the Church. Under the papal autocrat they placed episcopal autocrats by giving the bishop absolute control over his diocese. And they left no room for participation by the laity in the administration of the Church. In sum, they bequeathed to modern Catholics a highly authoritarian, centralized structure that was still basically medieval.

For the everyday life of the Church, probably nothing Trent did was more important than its reform of the Mass. The need for reform was obvious. The medieval Mass had become a theatrical-type spectacle, the faithful having lost the sense of participation that was at the heart of the ancient liturgy. Moreover, owing to the copying of liturgical books by hand and other factors, a great variety of local variations had crept in, some of them bizarre, disedifying ceremonies; and besides, there were celebrants who indulged their own eccentricities to the amusement and sometimes the scandal of the faithful. “A tangled jungle” is the way Jesuit scholar Joseph Jungmann describes the state of the Mass at the end of the Middle Ages. There was also a good amount of simony (priests hawking Masses) and superstition (Masses that had to be celebrated with twelve candles or seven candles or whatever in order to guarantee the promised benefits). The Protestants had been most vehement in denouncing such abuses.

The commission that Trent set up to reform the Mass did their work rather quickly, and in 1570 it issued the Missale Romanum, which was made binding on the universal Church and which remained virtually unchanged until the 1960s. Its introduction marked a new era in the history of the Mass: In place of the allegorical Mass there would now be the rubrical Mass—the priest being obligated under penalty of mortal sin to adhere to its most minute prescriptions. Here again it is the extreme conservatism of the council that strikes the eye. It is at least conceivable that they might have taken a creative approach. They might, for instance, have introduced the vernacular, which the Protestants had done so successfully. But instead they acted defensively and protectively. One reason for this was that in the polemical climate of the times they could not afford to admit that the Protestants could be right about anything. This would impugn the claim of the Roman Church to divine authority. Another reason was the still rudimentary state of historical knowledge. Scholars had not yet uncovered the complex history of liturgical evolution and the slow formation of the main liturgical families. Common opinion at the time believed that St. Peter had instituted the Catholic way of saying Mass.

The Tridentine Mass was tremendously effective in securing a uniform religious expression for Catholics throughout the world. And as a pedagogical tool for instilling the Catholic sense of tradition and emphasizing the clarity, stability, and universality of Catholic doctrine, it was superb. But on the negative side it helped engender the myth of the unchangeable Mass, the sign and proof of the unchangeableness of the Roman Church (a myth whose overthrow has lately caused such confusion). And above all it failed radically to restore to the people a sense of participation—forcing them to run after a multitude of extraliturgical devotions in order to satisfy their need to feel involved in the worship of the Church.

In spite of its notable limitations, the Council of Trent was certainly the pivotal event of the Catholic Reformation. It dramatically mirrored the vital spiritual energy once more pulsating through the Church; it defined the key doctrines of the Church; and it set the whole Church on the path of reform. All of this we can now see in retrospect. But at the time, any pessimist familiar with the history of the previous reform councils might well have wondered whether all those decrees might simply remain dead letters.

But the pessimists were wrong for a change. One of the main reasons for this was the Roman Popes, who fortunately for the future of the Church were sincerely dedicated to carrying out the reforms dictated by Trent. Without their dynamic leadership the cause of reform would certainly have remained a mere vain aspiration.

The first and greatest of these reform Popes was Pius V (d. 1572), previously renowned as a relentless inquisitor; he set such a high standard of papal morality that it has never again suffered any serious relapse. An ascetic, mortified man who loved nothing more than prayer, he transformed the Vatican—by rigorous measures and example—into a kind of monastery. Throwing himself into the work of reform with indefatigable energy, he published the Catechism of the Council of Trent, a clear, concise summary of Catholic beliefs and practices, and also the previously mentioned Missale Romanum,or Revised Roman Missal, which imposed a uniform liturgy on the whole Catholic world. But probably his most important contribution was cleaning out the long-entrenched curial bureaucracy, with its notorious policy of selling office to the highest bidder. Only a man of his tough fiber would have dared to tackle such a job, and he succeeded only by dint of heroic determination.

His successors kept steadily at the work of reform. Gregory XIII (d. 1585), who won a lasting niche in history by his reform of the calendar (1582), was not an ascetic like Pius. But assisted by Charles Borromeo, Gregory kept his administration fixed on the goals of reform. To guarantee the most rigorous execution of Trent’s decrees, he appointed a committee of four of the most zealous reforming cardinals. His successor, Sixtus V (d. 1590), was energy personified. Elected at sixty-five, he was an unhandsome man whose countenance was dominated by a large and heavy nose hanging over a dark chestnut beard tinged with gray; his arched and extraordinarily thick eyebrows framed small eyes whose glance was so piercing that one look from him sufficed to secure compliance. The towering obelisk he erected in St. Peter’s Square still reminds us of the imaginative and grandiose urban renewal programs he initiated. He was a man of big ideas, though some of them—like his plans to conquer Egypt—were too ambitious to carry out. He showed the sternness of his nature by the ruthless measures he took against the bandits who infested the Papal States. A report from Rome in 1585 stated that there were more bandits’ heads exposed on the bridge of St. Angelo than melons sold in the markets. On the other hand, he was less severe in his treatment of crimes against the faith. Only five persons were executed for this reason under Sixtus, three of them priests who were burned at the stake in one autoda-fé in 1587. Although he lapsed into some of the inappropriate fiscal policies of bygone days, he did continue the work of reform—appointing only men of sterling qualities to the cardinalate. He left behind a permanent mark on the Church’s administration by his reorganization of the Curia, which gave it the basic centralized and uniform structure it has retained throughout modern history.

St. Charles Borromeo. Orazio Borgianni (1578–1616). San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome. © Scala/Art Resource, New York.

At the death of Sixtus it was evident that the Popes once more had a firm hand on the helm of the Church. Though their domain was no longer the whole of Western Europe, as in the Middle Ages, they once again wielded an influence over the Church that they had not exercised since the Great Schism.

One of the most potent instruments used by these Popes of the Catholic reconquest was the Inquisition. A creation of the medieval papacy, it had fallen into virtual disuse—outside of Spain—until it was reconstituted by Pope Paul III in 1542. This Roman Inquisition, supplemented by the Congregation of the Index (established in 1571 and which periodically issued a list of condemned books), proved very effective in suppressing heresy in Italy and Spain. No one, however high in office, was beyond its fearful reach. The primate of Toledo, Archbishop Carranza (d. 1576), was himself arrested and kept for seventeen years in its prisons on the mere suspicion of heresy. Intolerance and repression, we might add, were not confined to the Catholics; Protestants also used similar coercive methods against dissenters.

BESIDES THE REGENERATED papacy, another institution proved of singular importance in the success of the Catholic reform: the Jesuit order. In fact, no single Catholic did more than its founder, Ignatius Loyola, to offset the devastation inflicted by Luther. Of course, the bantam-sized ex-soldier could not foresee this when he gathered a small band of men around him in Paris and induced them to join him in a little church on the hill of Montmartre in 1534 to take vows of chastity, obedience, poverty, and a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Loyola created a force that would help transform the Catholic Church and shape much of its history for the next four centuries. He was a God-intoxicated soul, a mystic with a unique genius for communicating his own love of God. His Spiritual Exercises— the fruit of his religious experience—became the chief instrument in molding the spirituality of his order and proved many times over their remarkable power of changing men. The effectiveness of this amazing little book was due to the extraordinary fashion with which Ignatius combined—by an uncanny instinct—the accumulated spiritual wisdom of the past with the immediate lessons he drew from his own unusual experiences. It deeply influenced the whole Catholic Reform movement by its insistence on the necessity of a profound interior life of prayer as the source of the apostolate and of all effective action in the Church. And as used by the Jesuits, especially in their retreats, it proved capable of being applied to men at all levels of spiritual need.

St. Ignatius Loyola receives the papal bull from Pope Paul III ordaining the Jesuit order. Juan de Valdés Leal (1622–90). Museo de Bellas Artes, Seville. © Scala/Art Resource, New York.

The Jesuits were committed to serve God by serving the Pope and the Church in whatever capacity they were needed. They were flexible and even revolutionary in the way they changed and even discarded traditional religious practices. Daily prayers in common according to a fixed schedule were dropped, for instance—a move that shocked contemporaries. They re-examined everything traditional, in fact, only retaining what promoted their pastoral aims and main tasks: preaching, giving retreats, teaching, and administering the sacraments.

The progress of the order was astounding. At the time of Ignatius’ death in 1556 it numbered some 936 members and had sunk its roots into most of the Catholic countries of Europe. Its members distinguished themselves in every form of the Church’s apostolate and won renown as preachers, builders, teachers, writers, founders of colleges, pastors of souls, and confessors. Many of them carried the Gospel overseas as missionaries. All in all, they engaged in a range of activity unparalleled by any of the other orders. The results were especially dramatic in German-speaking lands and in central Europe, where whole regions—including Poland in its entirety—were brought back to the Roman obedience.

Next to Ignatius himself, no Jesuit was more influential than Peter Canisius (d. 1597)—called the second apostle of Germany—a priest who engaged in a multifarious range of religious activities with singular success. Though the volume and manifold nature of his work had an almost chaotic effect on his daily life, he was able to remain essentially a man of prayer. He was a remarkably effective preacher, organizer, and confessor, but his greatest gift to the Catholic Reform movement in Germany was his Catechism—a compendium of Catholic doctrine that he published in varying forms to match different levels of age and education. It enjoyed over 130 editions and was so popular that, as Lortz says, Catholicism in Germany was henceforth inconceivable apart from it.89 We might add that from our standpoint today it compares unfavorably in some ways with the Roman Catechism of Pius V, which was more positive in its approach and more ecumenical: Pius’ work aimed mainly at the renewal of the inner life of the Church and presented the Christian message in more positive and comprehensive terms. Canisius’ catechism, on the other hand, shows how this earlier spirit of ecumenism was blighted by an increasing emphasis on controversy.

Canisius was also largely responsible for the foundation of colleges at Augsburg, Munich, and Innsbruck. This educational work was, in fact, one of the principal means used by the fathers in their efforts to promote the Catholic renewal. Here again they had a major influence on something quite new in the history of the Church—the founding of religious orders organized solely to carry on teaching as a Christian work of charity.

Besides the papacy and the Jesuits, the other major agency in the success of the Catholic Reformation was the bishops. The Council of Trent viewed the reform of the bishops as the key to the reform of the rest of the Church. They were ordered to reside in their dioceses and not leave without permission; they were to preach regularly, visit their parishes, hold annual synods, build seminaries, ordain as priests only candidates who were rigorously tested, root out concubinage among priests, keep an eye on the discipline of convents and religious houses, and give good example in their own dress, charity, and modesty. Their authority was strengthened to enable them to deal effectively with abuses.

It was a high ideal but not an impossible one, and soon there were many bishops who measured up to the standards set at Trent. The severely ascetic Charles Borromeo of Milan was undoubtedly the most important example of this reformed episcopate. From 1565 to 1584 he ruled the diocese of Milan, embracing more than a half million souls, where he followed the prescriptions of Trent to the letter. The reform legislation, which he promulgated in numerous synods, was copied by bishops around the Catholic world. Through his influence and that of other men, like St. Thomas of Villanuova (d. 1555), the spirit of Trent gradually penetrated the entire Catholic episcopate and stamped the entire Church with a characteristic physiognomy. A Catholic diocese would henceforth be run in military fashion. Trent’s strengthening of episcopal authority enabled the bishop to stamp out quickly any challenge to orthodoxy or uniformity.

IN CONJUNCTION WITH the Tridentine Reformation a new type of Catholic spirituality appeared that was to remain the standard for the following centuries. The Tridentine decree on justification stressed the importance of good works—exerting a decisive influence on the direction taken by this spirituality in the modern era. It meant that Catholics would conceive spiritual perfection as involving a high degree of personal activity—combining an active striving after self-control, the acquisition of virtue, and a zeal for the good works of mercy and charity. At the same time the decree also encouraged a meditative form of mental prayer, which was already highly cultivated in the fifteenth century. Under the influence of such masters as Loyola, Scupoli, Francis de Sales, Vincent de Paul, and de Bérulle, this developed into the very quintessential act of Catholic reform spirituality. A science of meditation originated, which became one of the most important tools used by Church leaders in the reform of clergy and laity.

To balance this emphasis on one’s own activity, there was an equal insistence on the priority of God’s grace; in a sense it is God who does all. And so there was also great emphasis placed on those visible channels of God’s grace—the sacraments. A eucharistic piety was fashioned that became the distinguishing feature of modern Catholicism: Devout Catholic laymen now began to receive Communion once a week and confessed their sins frequently rather than once yearly, as in the medieval Church. Many priests and bishops now began the daily celebration of Mass. This eucharistic piety was extended to include a wealth of nonliturgical practices, such as the adoration of the host in such services as benediction and forty hours.

Tridentine spirituality was then sacramental, centered on the Eucharist. It was exacting, making stiff demands on its practitioners: self-discipline, self-control, and regularity in prayer. It was practical in the way it closely associated good works with self-improvement. And finally, in accordance with the dominant cultural trend of the times, it was humanistic—at least in its assumption that each person had it in his power, to some degree, to determine his own fate.

This spirituality found its finest expression in a considerable number of vigorous, colorful men and women whose impact was strong enough to create distinct schools (Oratorian, Carmelite, Salesian, etc.) modeled after their example. One of the most influential of these saints was no doubt Philip Neri (d. 1595), founder of the Oratorians. A man who combined whimsical cheer-fulness and zest for life with a deep interior spirituality, Neri exerted extraordinary influence over people of every walk of life in Rome during the latter part of the sixteenth century, and as confessor of Popes and cardinals he assisted in the transformation of the Roman Curia itself. His school of spirituality—called Oratorian from the community of priests he founded by that name—included another outstanding exponent in the French author de Bérulle (d. 1629), a cardinal and leading statesman.

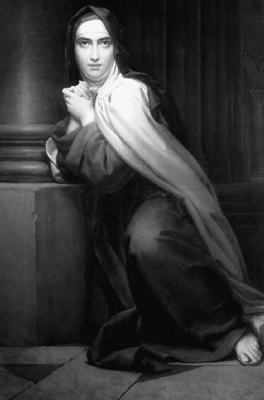

The leaders of the Spanish Carmelite school, Teresa of Ávila (d. 1582) and her friend and disciple, John of the Cross (d. 1591), were both reformers of their respective Carmelite orders in the face of savage opposition. Both were endowed with great mystical powers and both were gifted with unrivaled literary skill in depicting the various stages of mysticism. Teresa was the first to give a scientific description of the entire life of prayer—from meditation to the mystical marriage. Her finest mystical work is Las moradas or El castillo interior (1583). John’s best loved poems include Noche oscura del alma, Llama de amor viva and La subida al Monte Carmelo.

The Salesian school was founded by Francis de Sales (d. 1622), who as bishop of Geneva successfully accomplished the difficult and dangerous mission of winning the people of the Chablais district back to the Catholic faith. His writings are not only highly regarded guides to the spiritual life but also are considered among the classics of French literature.

Other notable examples of Catholic spirituality during this period were Jane de Chantal (d. 1641), the protégé of Francis de Sales who founded the Congregation of the Visitation Sisters, and Vincent de Paul (d. 1660), whose Congregation of the Mission (1625) did much to raise the standards of the French clergy. With Louise de Marillac he founded the Sisters of Charity in 1633, the first Catholic female religious society without enclosure. The sisters were dedicated to work among the poor and sick. Vincent’s life span coincided with a remarkable renaissance of mysticism in the French Church, when many saints of lesser fame also flourished.

St. Teresa. 1827. François Gérard (1770–1837). Maison Marie-Thérèse, Paris. © Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

ANOTHER MANIFESTATION OF the revitalized spirituality of the post-Trent Church was the imposing theological and intellectual revival associated with the leading Catholic universities: Salamanca, Rome, Paris, and Louvain. Central to the whole enterprise was the renaissance of interest in Thomas Aquinas, whose works, thanks to the Jesuits, won nearly universal acceptance as basic texts.

Robert Bellarmine (d. 1621), professor of theology at Gregorian University in Rome, was the most illustrious defender of the traditional faith in the polemics with the Protestants. His Disputationes de Controversiis Christianae Fidei (1568–93) was a massive, systematic presentation of the Catholic position. Its defense of papal prerogatives exerted enormous influence on the development of the doctrine of papal infallibility. His concept of the Church appears extremely juridical today, but it remained the standard Catholic one until Vatican II. His fellow Jesuit luminary, Francis Suarez (d. 1617), wrote commentaries on Aquinas marked by a definite originality. Suarez’s systematic approach and careful attention to historical data gathered from patristic and conciliar documents set a high standard for modern Catholic theology. Although his thought occasionally soared to the pinnacles of Trinitarian speculation, his most substantial contributions occurred in speculations about the nature of grace and in the field of international law.

Another sign of the spiritual energy stirring the Church to renew itself is found in the work of the missionaries who crossed the oceans in constantly increasing numbers during the sixteenth century. At the dawn of the age of discovery, Catholic priests would invariably accompany the explorers and, as they opened up a whole new era in Europe’s relations with the rest of the world, this missionary effort remained an important part of the whole enterprise. Prince Henry the Navigator’s pioneering explorations of the African coast led to the establishment of Catholic missions there. Then Columbus carried missionaries to America, where three episcopal sees were organized as early as 1511. These missions flourished and were the basis for the conversion of all of Central and South America.

Some attempts had been made during the Middle Ages to bring the Gospel to the Far East; the Franciscan John of Montecorvino went to Peking as archbishop in 1307. But the promise was cut short by the rise of the hostile Ming dynasty in China and the coming of the Black Death to Europe. The modern missionary movement to the Far East goes back to 1498, when the Portuguese reached India and made Goa the center of missionary work. But the really significant date is 1542, the year Francis Xavier, S.J., landed in Goa after a thirteen-month voyage from Lisbon and began to preach, baptize, and convert multitudes. After numerous trips to the cities and ports of India and Indonesia, he landed at Kagoshima in southern Japan. Two years later he set out for China but died on a desolate offshore island in 1552. The mission he left in Japan at first made progress, but a terrible persecution broke out in 1638 that took the lives of thirty-five thousand Christians and left behind only a remnant, who were forced to practice their religion underground until missionaries arrived again in the middle of the nineteenth century.

The Chinese mission dated from 1581, when a number of Jesuits led by Matteo Ricci arrived. Ricci won prestige among the Chinese by his scientific knowledge, his clocks, and his maps. He converted many Chinese by skillfully adjusting the message of Christ to accommodate Chinese ideas. But his toleration of the continuation of semireligious rites by Chinese converts later occasioned much controversy among missionaries and was only finally settled by Pope Clement XI (d. 1721), who decided against Ricci’s methods. This decision meant that potential converts were made to feel that accepting Christianity meant repudiating their whole culture. The tragic consequences of the Pope’s act coupled with the decline of Portuguese power in the East greatly crippled the missionary effort in China. As with Japan, the whole work had to be started over again in the nineteenth century.

A work somewhat similar to Ricci’s was begun in India by Robert de Nobili, S.J. (d. 1656), who adopted the lifestyle of the Brahmins. An eminent linguist, he wrote more than twenty books in Sanskrit, Tamil, and Telugu, including hymnals and catechisms. The most successful Catholic missionary effort in Asia took place in the Philippines, where a bishopric was set up in 1581. By 1595 a college was opened in Manila. Today there are some twenty million Catholics in the country, about 80 per cent of the population.

Until the end of the eighteenth century, missionary work was carried on almost exclusively by Catholics; but in the Far East, as we have seen, it had only marginal effect. In part this was a result of the advanced state of culture and religion among the natives, who were inclined to eye the foreigners with a certain disdain; it was also related to the missionaries’ close connection with European colonialism. A most important act for the future of the Catholic missionary effort was the establishment in 1622 of the papal Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith) whereby the Pope centralized all mission activity under his authority. It struck at the system of royal patronage, which enabled Catholic governments to control and often exploit the Catholic missionary movement for political purposes.

BY THE END of the Council of Trent in 1563 Protestantism had already established its sway over half of Europe. This trend was reversed, however, during the remainder of the century. With the publication of Trent’s decrees and with the upsurge of new vitality in the Church—manifest especially in the Jesuits and the regenerated papacy—the Catholic Church began to recover large blocs of territory. Poland turned back to Catholicism; large parts of Germany, France, and the southern Netherlands were likewise restored to communion with the Holy See, while the Protestants made no significant gains after 1563. And overseas Catholic mission gains compensated for the losses suffered in Europe.

One must not underestimate the part played by political forces in fixing the religious map of Europe in the sixteenth century. We cannot forget that there were inescapable political consequences involved in the decision to accept or repudiate Rome. It meant for each government having greater or lesser power over ecclesiastical affairs or the power to seize ecclesiastical property.

The most powerful late sixteenth-century monarch, Philip of Spain, was a zealous champion of the Roman Church and did all he could to restore Europe to obedience to the Pope. He launched his mighty armada in 1588 against England partly with this purpose in mind. Its defeat was a big setback for the political Counter Reformation. Elizabeth, Queen of England, for her part used political methods to fasten Protestantism on her kingdom. France was the theater of a seesaw struggle between Catholics and Huguenots that lasted forty years and only came to an end when the victorious Protestant King Henry IV embraced Catholicism and in his Edict of Nantes (1598) decreed freedom of conscience for all of his subjects. Sweden narrowly missed being forced back to the Roman obedience by its Catholic King Sigismund. He was defeated by his Protestant Uncle Charles at the Battle of Stangebro in 1598 and driven out of the country together with his Jesuit allies.

The last of these religious wars took place in Germany—the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48). It signalized the breakdown of the Peace of Augsburg (1555) and the increase of Catholic power in Germany thanks to the dynamism of the Tridentine reform. The Catholic Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand of Austria was victorious in the first phases of the war and was on the verge of establishing the political ascendance of Catholicism over Germany. But at this point King Gustavus of Sweden intervened—ostensibly to save the Protestant cause. But his alliance with a cardinal, Richelieu of France, against Catholic Austria in 1631 showed how political considerations had already begun to overshadow religious ones in the grand game of European politics. The Treaty of Westphalia (1648) brought the Thirty Years’ War to an end. Catholics, Lutherans, and Calvinists were accorded equality before the law in Germany.

It was certainly clear at this point that the unity of medieval Christendom was gone forever. The demarcation of territory between the Catholic Church and other forms of Christianity was settled for the next three hundred years. It was significant that the most populous countries and (except France) the most powerful ones—the ones that were in the next century to dominate diplomacy and politics—England, Sweden, and Prussia—had all turned Protestant.

The post-Trent Church obviously could not hope to dominate Europe as the medieval Church had. But thanks to the Council of Trent and the tremendous movement of reform it engendered, the Catholic Church in the seventeenth century was once more a strong, self-confident, spiritually revitalized organization. Faced with a phalanx of innovators who seemed bent on jettisoning the entire medieval heritage, the bishops at Trent had reaffirmed almost every jot and tittle of the tradition. It was a rigoristic and authoritarian institution they set up, but it was also a dynamic spiritual force capable of meeting once more the religious needs of a large portion of the human race. Thanks to Trent, the Pope was once again in complete command of the Church. Under him and with the help of the regenerated old orders and enthusiastic new orders and aided by the better-trained diocesan priests, the bishops were able to carry out a vast reformation. On every front—spiritual, intellectual, cultural, and missionary—they scored great victories. The spiritual élan of this Tridentine Church was marvelously captured in stone by the twin masters of the baroque, Bernini and Borromini. Under papal patronage, they filled Rome with fountains, statues, and churches in the new style to celebrate the resurrection of the Church of Rome. Two of them are of incomparable power: Bernini’s immense elliptical colonnade that frames the piazza of St. Peter’s, and his towering, twisting bronze baldachino over St. Peter’s tomb. Contemplating them today one can still feel the excitement and the drama of this amazing chapter in the history of the Church.