Chapter 23

THE CHURCH TORN BY INTERNAL STRIFE: JANSENISM AND GALLICANISM

While the Church continued to lose ground in its struggle with critical rationalism and liberalism during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was also weakened interiorly by several violent controversies—over Jansenism and Gallicanism—which divided it and hindered it from adequately responding to the free thinkers.

Jansenism originated with the bishop of Ypres, Cornelius Jansen (d. 1638), a professor at Louvain University, whose book Augustinus was only published after his death. Jansen appealed to the authority of St. Augustine in expounding theories on the nature of original sin, human freedom, and the nature and efficacy of God’s grace. At the root of his system was a belief in the radical corruption of human nature, which to the authorities smacked suspiciously of Calvinism. After a decade of violent debate in France his whole theology was examined by a papal commission at the request of the French bishops, reduced to five succinct propositions, and condemned by Pope Innocent X in the bull Cum Occasione of 1653.

But this did not put an end to the affair. Jansen’s followers, led by Antoine Arnauld (d. 1694), and with unofficial headquarters among the nuns of the convent of Port Royal, refused to capitulate. They trumped up a clever distinction between “fact” and “law” to salvage their orthodoxy: The five propositions condemned by the Pope were indeed heretical, they maintained, but they did not accurately reflect the true doctrine of Jansen’s Augustinus. Moreover, the identity of the five propositions with the authentic teaching of Jansen, they asserted, was a question of fact and as such did not fall under the purview of the Church’s infallibility. The French Assembly of the Clergy, however, in 1654 affirmed—to the contrary—that the doctrine condemned by the Pope was indeed identical with Jansenism.

Cornelius Jansen, bishop of Ypres (1585–1638), signed Louis Dutielt and dated 1659. Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles. © Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, New York.

But the Jansenists were able to hold their own; their convent of nuns at Port Royal was famous for its austerity, its intense contemplative life, its studious atmosphere, and the many novices it attracted; it served at the same time as a center for an intellectual and spiritual elite of Paris who included some of the most influential members of Parisian society. Their most valuable convert was the brilliant mathematician and inventor Blaise Pascal, who after joining their ranks penned in their defense his masterpiece of satire, the Provincial Letters(1656–57)—a devastating attack on their chief enemies, the Jesuits.

The Jesuit and the Jansenist theologies proceeded from a different view of the nature and effects of original sin—coming to different conclusions on a number of crucial points. According to the Jansenists, original sin completely vitiated human nature, subjecting man to concupiscence, unruly passions, all imaginable physical and psychic ills, ignorance, and finally death. The Jesuits, on the other hand (following their favorite authority, Luis Molina [d. 1600]), did not subscribe to so pessimistic a view of the effects of original sin; they held that it merely deprived man of the supernatural gifts bestowed on him—leaving him in the condition of nature, in possession of the powers and subject to the debilities he would have had if he had never been raised to the supernatural state.

Both views had important implications for morality. Because of their optimistic view of human nature, the Jesuits stood for a morality that in many ways resembled the purely naturalist morality of the enlightened Deists and rationalists. Like them they preached the dignity of human nature, and like them they made “nature” the norm of morality, although they did not understand nature in exactly the same way. The Jesuits affirmed that even without grace a person could observe moral rectitude at a natural level and by his own free will perform acts that were morally good.

The pessimistic theology of the Jansenists was reflected in their moral rigorism; since they held that without the constant help of grace man remained totally depraved, all his actions were wicked and even his pretended virtues were vices. Grace was only given to the predestined; others were inexorably doomed to eternal punishment for their sins through no fault of their own, since they simply did not receive the necessary grace.

From the start the Church leaned toward the Jesuit theology and eventually decided in its favor. It was definitely more suitable for a Church that aimed to embrace all men and that traditionally offered a saving grace in its sacraments that was available to all, and that always taught that human effort counted for something in the work of salvation.

But for a time Blaise Pascal and the Jansenists were able to put the whole Jesuit system of morality in a bad light. They accused the Jesuits of preaching an easygoing morality in order to gain power and influence over the masses. By an ingenious use of quotations from Jesuit authors in his Provincial Letters,Pascal won over a considerable number of readers. Fortified by the support of public opinion and led by the indomitable Arnauld—an incredibly prolific writer—the Jansenists continued to defend their position and won over some of the clergy and even some of the bishops.

Finally, the Jansenists were ordered by the King, Louis XIV, and the Pope, Alexander VII, to sign a statement renouncing their errors. Under extreme pressure they resorted to another stratagem—the position of “respectful silence”—meaning that while refusing to accept papal infallibility as to questions of fact, they promised to maintain a respectful silence regarding the accuracy of the papal bull. At this point a new Pope, Clement IX (1667–69), was elected, and as a desire for peace was manifest on both sides, a truce was arranged whereby the Jansenist bishops signed the formulary with certain reservations of their own.

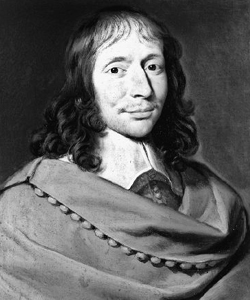

Blaise Pascal. Philippe de Champaigne (1602–74). Private collection, Paris. © Giraudon/Art Resource, New York.

An uneasy peace ensued during which the Jansenists, led by Arnauld, fortified their position. Pope Innocent XI (d. 1689) himself seemed to lean in their direction by his condemnation of 65 propositions drawn from Jesuit moral authors; the Jansenists also had the satisfaction of seeing one of their sympathizers, De Noailles, consecrated archbishop of Paris. However, a new offensive was mounted against them at the turn of the century when the Jesuits attacked Quesnel, Arnauld’s successor, whose book Réflexions Morales (1693) reaffirmed all the substantive tenets of Jansenism. The recently elected Clement XI (d. 1721) was also unfavorably disposed, and in his bull Vineam Domini (1705) he condemned their tactic of “respectful silence.” The King drove the nuns out of Port Royal and leveled it to the ground. Finally, Clement launched his bull Unigenitus, which condemned 101 propositions drawn from Quesnel’s book. The reaction revealed a deep division in the French Church; sixteen or so bishops, led by the cardinal archbishop of Paris, and a large number of the clergy refused to submit, claiming that a papal bull was infallible only if it obtained the assent of the universal Church, and they appealed over the head of the Pope to a future general council.

But the Jansenists were unable to maintain their position. Cardinal de Noailles submitted in 1728, the Sorbonne in 1730; by 1760 only half a dozen bishops showed any Jansenist leanings, and their support was mainly confined to the lower clergy and laity. They became a small, hunted, and persecuted sect, but with the exception of the Dutch Jansenists, who nominated for themselves a schismatic bishop of Utrecht, they never formally broke with the Catholic Church.

Gallicanism was another movement that greatly agitated the Church during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Gallicans were opposed to Roman papal centralization and wanted to restrict the scope of papal interventions in the affairs of the national Churches. They also insisted on the dignity and independence of the bishops and severely limited papal authority over temporal rulers. On the theological level, they denied the personal and separate infallibility of the Pope, since they held that infallibility belonged only to the whole Church and therefore could be expressed either through general councils or through papal decisions if these were ratified by the assent of the universal episcopate.

Though Gallicanism received its name from the French Church (in Latin, ecclesia gallicana) it was not a phenomenon restricted to the French Church. In part it reflects a general trend of European governments to subordinate the Church and make it a department of the state. Whether we take the Church of England, the Lutheran Churches in Germany and Scandinavia, or the Catholic Churches in the Habsburg or Bourbon dominions, the picture is basically the same: a tight union of Church and state, with the Church reduced to the junior partner.

The Catholic Church, with its independent head located outside the country, was in a better position to resist the trend. But even in Catholic countries the monarchs managed to obtain a large amount of control over their Churches. By concordats, for instance, the Bourbons and Habsburgs acquired the right to nominate bishops and to prohibit the publication of papal decrees.

In the latter part of the seventeenth century, Louis XIV nearly led the French Church into schism in his efforts to dominate the Church.

Louis was the greatest monarch of the time and carried France with him to the pinnacle of European power. After finally stripping his nobles of their power, he brought them to Versailles to ornament his grandiose palace. With the aid of ministers of genius such as Colbert and Louvois, he succeeded in greatly strengthening the national economy, establishing sugar refineries, iron works, glass factories, and textile industries to enrich his nation of twenty million people. The army organized by Le Tellier and Louvois reflected the strong centralization Louis imposed on France; no longer were its commanders to run things on their own—from top to bottom, its four hundred thousand men were subjected to elaborate discipline. In his foreign policy, Louis was intent on extending the frontiers, with the ultimate aim, it seems, of restoring the Holy Roman Empire, with himself wearing the imperial crown.

Louis XIV of France (1638–1715), painted in 1701. Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659–1743). Louvre, Paris. © Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, New York.

In his policies toward the Church, Louis was governed by the prevailing Gallicanism and constantly encroached on the spiritual power. He unilaterally extended the royal right of regale, a traditional prerogative that allowed the King to administer and appropriate the revenue of a diocese and make appointments on the death of a bishop and during the interim before the election of a new bishop. In flagrant contempt for Canon Law, Louis extended this right to cover the new territories conquered by his army.

The Pope at the time, Innocent XI (d. 1689), austere, scholarly, unworldly, beloved for his piety and generosity, would not be intimidated by the awesome power of the “Sun King.” He dispatched a brief condemning the King’s action and entreating him to forgo the right of regale. At first the King tried to evade the issue. But when the Pope insisted and even threatened Louis with spiritual sanctions, Louis finally resorted to a time-honored custom: He rallied the clergy to his side and hurled his defiance.

The Assembly of the Clergy, which he convoked, lasted from October 30, 1681, to May 9, 1682. Under the leadership of bishops like Bossuet, whose sermon “On Unity” urged the prelates to moderation, it formulated its Gallican standpoint in the notorious Four Articles. While acknowledging the primacy of the Popes as successors of Peter, the articles denied their authority over temporal affairs; reasserted the validity of the decrees of the Council of Constance, which affirmed the superiority of general councils over a Pope; made the authority of papal decrees conditional on their acceptance by the Church; and rejected the separate infallibility of the Pope.

The King ordered these articles to be taught in all universities and seminaries as official doctrine. Rome was outraged; in its eyes the Assembly had overstepped the bounds of its authority by treating of matters that properly belonged only to a general council. Moreover, the declaration itself was seen as opposed to the constant teaching of theologians and hence were at least suspect of heresy.

A veritable war broke out between France and the papacy, which lasted until the death of Innocent in 1689. But both sides refrained from pushing the matter to its logical conclusion: schism. The Pope refused to canonically install the King’s episcopal nominees—which soon left many dioceses without bishops. The King threatened Italy with invasion and seized the papal province of Avignon, but as a recent convert to a devout practice of the Catholic faith he resisted the temptation to take the fatal course of Henry VIII.

The intransigent stand of Innocent proved wise in the long run. After his death a compromise was arranged: The King agreed not to require the teaching of the Four Articles, while the Pope yielded on the matter of the regale. The issue of papal infallibility was side-stepped, since it was not yet considered ready for definition. Gallicanism, therefore, as a theological position—covered by the authority of the incomparable Bossuet—continued to be taught in the universities and seminaries, and in its parliamentary form it dominated Church-state relations during the eighteenth century. But by his firm handling of the crisis, Innocent prepared the way for the papacy’s eventual victory over Gallicanism two centuries later at the First Vatican Council.

Gallicanism was also sprouting in German soil, and in the eighteenth century it took a form named Febronianism, after its leading spirit, Nicholas von Hontheim (d. 1790), who wrote his tracts under the pseudonym of Febronius. Like Gallicanism, it espoused the superiority of a general council over a Pope, the right of appeal to a general council against a papal decision, the denial of the separate infallibility of the Pope, and affirmation of the divine right of bishops. Moreover, the Pope was allowed no direct jurisdiction over the affairs of the individual Churches. It was also ecumenically oriented in its program of reform, aiming at a restoration of the Church to the primitive purity of its original constitution in the hope of rendering possible a complete reunion of all the Christian Churches. A major source of its inspiration was extensive historical research into the history of the early Church.

Febronius’s ideas found a ready acceptance among the German prince bishops who chafed at the controls exerted over them by the papal nuncio and Curia—controls that were doubly odious since they were much tighter in Germany than in other countries, where royal absolutism generally kept the Curia at bay. Sixteen of the twenty-six German bishops refused to publish Rome’s condemnation of Febronius; his own superior, the archbishop-elector of Trier, would not take action against him. Hontheim, himself, however, finally submitted and wrote a somewhat ambiguous retraction. But his ideas continued to ferment, and in 1786 the archbishops of Cologne, Trier, Mainz, and Salzburg met at Bad Ems and issued a kind of declaration of episcopal independence from Rome that closely adhered to Febronius’s program. It failed to rally the other German bishops, however, who in the crunch preferred Rome’s yoke to that of the archbishops. But Febronian episcopalianism was only definitively stamped out, like Gallicanism, at Vatican I.

All told, the eighteenth century was not a great era for the papacy. Challenged in its spiritual authority by Jansenists, Gallicans, and Febronians, it also suffered from the constant encroachments of the secular governments on its traditional rights and prerogatives.

The big rival Catholic powers—the Bourbons and Habsburgs, rulers of France, Spain, and Austria—exerted heavy influence on the papal elections, and by their power of veto were able to block any candidate regarded as unfriendly to their interests. This meant that the men elected were invariably compromise candidates. As a consequence, the eight Popes who ruled from 1700 to 1800 were, with the exception of Benedict XIV (1740–58), mediocre personalities—several of them very old when elected, one being nearly blind—and unable to reverse the constant decline in the Church’s fortunes and influence.

Moreover, their spiritual authority was gravely compromised by their status as temporal rulers of the Papal States—still as in the Middle Ages a narrow strip of land, economically poor and with the reputation of being one of the most weakly administered and backward countries of Europe. Theoretically the Papal States were supposed to guarantee the spiritual independence of the Holy See, but actually they often forced it into the game of shifting alliances and power politics at the expense of its spiritual mission. The atmosphere of the Curia struck many observers as unreal; its official communiqués, couched in pretentiously grandiloquent terms, were in glaring contrast with its actual prestige. And as the century wore on, much of the intelligentsia of Europe came to regard the Roman Church as a venerable anachronism more and more identified with political and social structures doomed to collapse as the world moved toward a profound transformation.

This weakness of the papacy was clearly revealed in the suppression of the Jesuits. The most successful of the orders founded during the Catholic Revival of the sixteenth century, the Jesuits consistently held their membership near the thirty thousand mark and maintained leadership in many fields of the Church’s apostolate—theology, teaching, the missions. They even succeeded in stamping the whole Church with their characteristic form of spirituality, with its emphasis on the practical and its exuberance in external devotions. Of course, their very success soon gained them an abundant supply of enemies and critics: Jansenists, who accused them of dispensing cheap grace and encouraging laxity in their moral direction; Gallicans, who resented their zealous loyalty to the Pope; resentful politicians, who envied their influence as confessors of Kings and princes. Nevertheless, they seemed stronger than ever at the beginning of the eighteenth century. But then a swift decline began, which finally ended in their suppression by Pope Clement XIV in 1773.

Why? Some point to the Jesuits’ reputed arrogance and to an exaggerated esprit de corps that alienated the sympathies of many would-be friends. But more important, it seems, was their failure to adapt intellectually to the demands of the age; they were the most respected and progressive educators in the seventeenth century, but they failed to keep up with the progress of the exact and experimental sciences. The Jesuits were also too conservative in theology and philosophy and so lost their pre-eminent position in these domains also.

In addition, a series of mishaps occurred in the eighteenth century that exposed them to the vengeance of their numerous enemies. First, there was the papal condemnation of their mission strategy in China, which embraced a policy of accommodating the Christian faith to Chinese Confucianism and ancestor worship. Their opponents, the Franciscan and Dominican missionaries, accused them of making dangerous concessions to paganism. Finally, Pope Clement XI condemned the Jesuit practice in his constitution Ex Illo Die (1715), reiterated by Benedict XIV in 1742.

Another severe blow to their prestige struck when they came into conflict with the Portuguese and Spanish governments over a communal system they had developed in Paraguay to protect the Indians from exploitation by colonial traders. The Jesuits were accused of fomenting revolution among the Indians and were chased out in 1750. The whole affair aroused the enmity of the two governments against the Jesuits.

The final blow fell with the financial collapse of the order in France, caused by an enterprising wizard, Father Lavalette, who ran a maritime business that practically monopolized commerce with the island of Martinique. When his company went bankrupt, the whole Jesuit order in France was made to bear the responsibility. All of its property in France was confiscated, and the order itself was completely suppressed in France in 1764. They were also driven out of Spain and Portugal at the same time.

It only remained for a Pope to be elected who would succumb to the mounting pressure from all sides for the complete suppression of the order. This happened in 1769 with the election of Clement XIV (Ganganelli), a man of rather weak character, whose promise to suppress the Jesuits undoubtedly figured as a prime factor in his election. The suppression was an ugly affair. The Pope showed less than candor in his letter of suppression, which made no mention of the political pressures involved. The Jesuit general was thrown into prison, where he died in misery. It meant the destruction of some six hundred religious houses, the closing of hundreds of schools, and the uprooting of over twenty thousand priests and brothers. It was indeed a fitting prelude to the terrible disasters about to afflict the whole Church.

During the eighteenth century the Church reached a nadir of its prestige and influence. The scholastic and sterile controversy over the nature of grace, the decline of the papacy’s vigor, the suppression of the Jesuits, the failure to come to terms with the new insights of the philosophers and scientists—these are only some of the manifestations of a general spiritual and intellectual debility. There were also others we have not discussed, such as the languishing of missionary effort and the decadence of the religious orders. No doubt a major cause of this dismal state of affairs was the alliance of throne and altar that had come to mean in practice the subjection of the Church to the state. But extricating the Church from a system that had lasted since Constantine could hardly occur without a tremendous social and political upheaval.