Chapter 24

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION SHATTERS THE CHURCH OF THE OLD ORDER

In spite of the many signs of interior decay, the Catholic and Protestant Churches of Europe in 1789 were outwardly prosperous and powerful—if anything, too much an integral part of the social order. They were established as official religions, and their hierarchies held privileged positions and enjoyed all the prerogatives and trappings of the aristocracy. This union of Church and state was a system that had lasted more than a thousand years and seemed destined to go on for yet a long time. But the storm of revolution suddenly burst across France and then Europe as a whole, and struck the Churches everywhere with a hurricanelike force. The first to feel its full impact was the French Church, which was so gravely shattered by the blow that it could never permanently recover its traditional dominant position. Catholic Churches elsewhere in many cases soon met a similar fate. The Protestant Churches were not as severely affected at first, but the forces set in motion by the revolution—liberalism and democracy—eventually had a similar disrupting effect on all the Churches.

IN MANY WAYS the French Revolution was the climax of the Enlightenment. The French Revolution began as a nonviolent experiment in reforming the French Government: Twelve hundred selected deputies came to Versailles from every corner of France at the bidding of the King to solve a grave financial crisis in the spring of 1789. Once gathered there, the six hundred commoners or Third Estate decided that France needed a much more radical and comprehensive reform than any envisaged by the King. They wanted to replace the ancien régime by a society based on the political and economic ideas of the Enlightenment, the experience of the British with representative government, and the social and economic realities of late-eighteenth-century France. This meant doing away with all privileges due to birth, giving the middle class political power, and putting an end to arbitrary government. They also stood for complete economic freedom and abolition of all controls—allowing each the unrestricted enjoyment of his private property. Feeling themselves the vanguard of a European crusade, they hoped to build a society that would be more efficient, more humane, and more orderly than the old order was.

The first step they took was to declare that Louis XVI would no longer be allowed to rule as a monarch by divine right but would have to share his power with the elected representatives of the nation. At first, the King and the nobles resisted this startling proposal. But in their oath taken on the Tennis Court (June 20, 1789), the Third Estate manifested its unflinching determination, and when the King ordered them to desist, they defied him. Unwilling or unable at the moment to use force, Louis capitulated and allowed them to meet as the National Assembly.

The Revolution turned bloody when Louis brought in mercenary troops to re-establish his absolute power. The people of Paris stormed the Bastille and formed their own army, the National Guard, while a general uprising throughout the country put power in the hands of the revolutionaries. No longer master of events, the King was left with no option but submission. His only chance of retaining some measure of authority depended on how skillfully he would deal with the National Assembly. As it turned out, he gradually alienated public opinion by engaging in treacherous plots against the Revolution, and so brought on his own execution and the establishment of the Republic.

As an integral part of the old order, the Catholic Church was bound to be intimately affected by its overthrow. But few at the outset seemed to have any presentiment of the tremendous upheaval in store for an institution that in 1789 held a privileged position as the only form of public Christian worship allowed by the state; whose hundred thousand or so clergy—the First Estate—formed virtually a state within the state and controlled all education and public relief; whose parish priests were the sole registrars of births, marriages, and deaths; and whose officials had power of censorship over publications deemed harmful to faith and morals.

There were, it is true, signs of a widespread impatience with the organization of the Church, as indicated in the cahiers—petitions for reforms drawn up by the voters. The cahiers called for sale of Church lands, end of payments to Rome, and the reduction or dissolution of the monastic orders. Again, Voltairean skepticism had made some inroads, especially among the aristocrats and upper levels of the middle class. But the Church still had a strong hold on the majority of Frenchmen.

At first there was no conflict between the Revolution and the Church. The clergy, in fact, acted as saviors of the Revolution when they voted with the Third Estate against the nobility and the King in favor of constituting a National Assembly. And the clergy continued to co-operate by willingly surrendering their privileges; they even accepted the confiscation of the Church’s extensive property (with its consequence the suppression of the religious orders)—a measure taken to deal with the country’s bankruptcy.

On their part, the laymen of the National Assembly showed at first no animus toward the Church. They agreed to recognize the Catholic Church as the official form of worship, even though—against clerical wishes—they accorded civil rights to Protestants and Jews. But the leaders soon blundered into a quarrel with the Church—provoking a schism between the Church and the Revolution that retarded for over a century the reconciliation of the Church and liberalism.

The conflict with the Church began when the Assembly took up the reform of the Church—embodied in the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. As with all areas of French life, such a reform was long overdue, as the clergy themselves were ready to admit. Nor was there repugnance at the idea of the state undertaking such a reform—it seemed a logical corollary of the union of Church and state. Moreover, many of the reforms proposed were obvious and well thought out: The parasitic chapters attached to cathedrals were swept away; pastors were at last to be given a decent income; and new and logical parochial and diocesan boundaries were drawn up.

But the decrees went beyond the reform of abuses and aimed at a revolution of the Church’s structure: They democratized the French Church, eliminating all control of the Pope over its internal affairs, providing for election of bishops and priests like other civil servants. Then they took the fatal step— the capital error that was to split France and the Revolution right down the middle: They tried to force the clergy to accept this radical reform of the Church by imposing on all Church office-holders an oath of compliance that they could not refuse without forfeiting their office. It was formulated with deliberate ambiguity; it obliged them to “maintain . . . the Constitution decreed by the National Assembly and accepted by the King,” so that those who refused could be accused of being disloyal to the Revolution.

A compromise might conceivably have been worked out. One thinks of how Napoleon and the Pope later on were able to reconcile differences over the reorganization of the French Church through long and patient negotiations. But the National Assembly showed little disposition toward compromise. They remembered how cavalierly Joseph II had reformed his Austrian Church, how Catherine II of Russia had reorganized the Polish dioceses. Perhaps they genuinely believed their reforms only embraced temporal matters. Perhaps they did not believe bishops and priests heroic enough to sacrifice their revenues and their livelihood over a matter of principle or that priests would desert the Revolution that the priests themselves had helped create.

In any event, there were two ways that approval of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy might have been secured: either through a national council of the bishops or by appeal to the Pope. The first method was ruled out by the National Assembly for fear that such a council might become a forum for counterrevolutionary propaganda. So the clergy were left with only one alternative: to appeal to the Pope to authorize them to accept. Pius VI, an absolute monarch himself and already very cold to the French Revolution, took eight months to come to a decision: On March 10, 1791, he issued a condemnation and forbade the clergy to take the oath.

But by this time the French clergy had already been forced to declare themselves. The previous January they were presented with the oath and made to decide. All but seven of the bishops and about half of the clergy rejected the oath. While many of the bishops as members of the nobility may have been motivated by plain hatred of the Revolution, this would not account for the lower clergy, many of whom were profoundly committed to the Revolution and its promise of social regeneration. Moreover, by refusing they exposed themselves to privation, exile, and even death. But their primary allegiance was to the Church, whose spiritual sovereignty they felt was at stake in the matter. It seemed clear to them that the representatives of the nation had violated this sovereignty by legislating in matters ecclesiastical on their own authority and in high-handed fashion demanding adherence to their decrees before the Church itself had spoken.

On the other hand, those who took the oath could invoke honorable arguments for their stand. They believed that in taking the oath to the “Constitution” they were merely giving a broad general assent to the new order in France, not necessarily approving of its specific religious stipulations. After all, they could reassure themselves, the King had himself accepted it, and they could assume that the Pope—whose delay in the meantime was most perplexing—would likewise yield. They could also appeal to Gallican precedents. Unfortunately, their bishops were of little help in the quandary, with their tradition of aloofness from the lower clergy and their obvious identity of interest with the old regime.

In this state of confusion and ambiguity, it was only natural for the priests in any one area to stick together for mutual support. This would explain the pattern we find. In some parts, 80 per cent or more of the clergy refused the oath, while in others a similar percentage accepted it. The Civil Constitution was almost totally accepted in the center, the Ile de France, and the southeast, and almost totally repudiated in Flanders, Artois, Alsace, and Brittany.

Henceforth two Catholic communities faced each other in almost every town and village of France: the Constitutional Church, led by the bishop and clergy who took the oath and who were installed in their posts after election by the people; and the nonconstitutional or nonjuring Church, whose clergy remained loyal to Rome. Farce and tragedy often intermingled when a constitutional priest came to take possession of a parish where sentiment ran high in favor of the incumbent nonjuring priest. In one town someone put a cat in the tabernacle, which jumped out and clawed the face of the new priest who unsuspectingly opened it during Mass. One poor constitutional priest made the mistake of accepting a dinner invitation from a dissident parishioner, who split his skull with a hatchet as he crossed the threshold.

At first, the nonconstitutional priests were only subject to ouster from their rectories and churches. However, the mere fact of refusing the oath to the Civil Constitution was enough to render them suspect of disloyalty to the Revolution itself in the eyes of many. They were lumped with the aristocrats who were openly or secretly scheming to overthrow the Revolution.

The logic of events soon fortified these suspicions and made the position of the nonconstitutional clergy very precarious. Nor were they helped by the papal legate to Germany, who preached counterrevolutionary sermons to French aristocrat refugees. The flight of the King also affected their situation adversely, since he openly displayed his sympathy with the nonjuring clergy, and his treason seemed to implicate them. Finally, when Austrian and Prussian troops invaded France to put down the Revolution, a persecution began of all those looked on as potential traitors. A savage decree was passed on May 26, 1792: Every nonjuring priest who was denounced by twenty “active” citizens was to be deported. Some thirty thousand to forty thousand priests were thereupon driven out of their native towns and hounded into hiding or exile. Later (on March 18, 1793) the death penalty was imposed on those deportees who dared to return. But even at the height of the Reign of Terror a good number of nonjurors heroically remained and exercised their ministry in cellars and garrets, offering Mass for a handful of faithful or giving absolution surreptitiously to upcoming victims of the guillotine.

The first slaughter of priests occurred as the Duke of Brunswick approached Paris with his hussars. With the city in the grip of hysteria and panic, a mob rushed to the prisons, whose inmates were considered the chief source of conspiracies against the Revolution. It so happened that the first victims taken and lynched were 20 priests awaiting deportation, and in the bloodbath that followed from the second to the fifth of September, 3 bishops and 220 priests lost their lives.

But for the loyal constitutional clergy, things went well at first. They intoned the traditional “Te Deum” to celebrate the victories of the revolutionary armies and proclaimed new laws from their parish pulpits. But these happy relations did not last long. After the overthrow of the monarchy, friction developed between the constitutional Church and the state, and relations became increasingly abrasive. Political factors may have had something to do with this: The clergy as a rule were still royalist and opposed the execution of the King; many of them were linked with the Federalist movement, which flared into open rebellion in Bordeaux in May of 1793.

But actually more fundamental reasons were responsible: The Revolution began to take on the character of a religion in itself. Some of its patriotic ceremonies featured sacred oaths and sacred trees, and some of the localities substituted patriotic names for the religious names of its streets. Compiègne replaced the names of the saints with revolutionary heroes, as did many others. Infants were given “un-Christian” baptismal names. Church bells and chalices were seized and melted. The resulting tension between the values of the Revolution and those of Christianity was exacerbated by the anticlericals, who attacked the clergy for being different: Why shouldn’t they get married like everyone else and increase the number of patriots?

It was only one step from this to the effort to uproot Christianity from France altogether. The first move in the dechristianization was the adoption of the Republican calendar on October 7, 1793. It was designed to remove all vestiges of Christianity: The Gregorian calendar was discarded; the Christian Sunday and the seven-day week were suppressed, and a ten-day week was put in its place; all religious holidays were canceled, and all reference to the birth of Christ was dropped by establishing a new era dating from the start of the French Republic, September 22, 1792. The new calendar was supposed to epitomize the cult of “reason” and reverence for an idealized “nature.”

The second move to dechristianize France began in the provinces under the aegis of the agents of the National Convention—men sent out with virtually unlimited powers to deal with the emergency situation created by the invasion of France and the counterrevolution within the country itself. One of these, a fanatical, bloodthirsty ex-priest named Fouché, opened up a dechristianizing campaign in the Church of Saint-Cyr at Nevers on September 22, 1793, by unveiling a bust of Brutus, a saint to revolutionaries, and denouncing “religious sophistry” from the pulpit. Thenceforth, wherever he traveled he turned the churches into “Temples of Reason” and presided over ceremonies that caricatured the Catholic liturgy; he pressured the clergy to resign and to marry, he ransacked the churches and ordered the burial of all citizens in a common cemetery whose gates he marked with a sign: “Death is an eternal sleep.” A host of imitators soon undertook the same kind of tactics throughout France.

Paris had to show that it was not to be outdone by the provinces. Its churches were all closed by order of the Commune. Its constitutional bishop, Gobel—poor man—was startled out of his sleep and ordered to resign by a band of sansculottes (the proletariat have-nots). He obliged them and went back to bed. The new cult of Reason was celebrated with great éclat in Notre Dame, where an actress was enthroned on the high altar as Reason’s goddess.

One of the most formidable voices in the anti-Christian chorus was Hébert, hero of the Parisian underdogs; his journal, Père Duchesne, specialized in scathing denunciations of rich and corrupt politicians. But he reserved his juiciest four-letter words for the priests—power-mad hypocrites, he called them, who betrayed Jesus, “le bon sans-culotte”— the best Jacobin who ever lived.

Regional studies, while not complete, show that by the spring of 1794 the dechristianizers had achieved a wide measure of success. The cathedrals and parish churches of most towns and villages were turned into “Temples of Reason.” But in rural France, where the majority clung to the old religion, the operation could only be carried out by armed force.

Many priests and even bishops abandoned their ministry—some of them taking wives as a proof of their break with orthodox Catholicism. At Beauvais about fifteen priests, including the bishop, married, and by 1803, a total of 50 of the 480 priests in the Department of the Oise had done so. All told, about 4,000 priests married during the Revolution. The motivations, as one would suspect, were mixed. Many were only temporizing until better times and simply married their housekeepers pro forma. Others used dechristianization as an excuse for doing something they had always wanted to do. Some justified themselves by pointing out that celibacy was merely an ecclesiastical law.

A number of renegades willingly defrocked themselves and even took a lead in the dechristianization, and like Fouché and Lebon, figured prominently in the chronicle of sacrilege. Some of them embraced the social egalitarian ideas of the extreme left; others succumbed to the fashionable sexual romanticism spawned by writers like Rousseau. But most of those who abdicated did so under pressure and in desperate and feverish circumstances.

The total number of priests who put aside the cloth would, it seems, number around 20,000—most of them constitutionals who were an easier target for the dechristianizers than the nonjurors, most of whom had already been forced to emigrate or go into hiding. But though acting under compulsion, their “apostasy” had the effect of wrecking and discrediting the constitutional Church.

In attempts to destroy Catholicism, the dechristianizers did not intend to leave a religious vacuum, for they still shared the ancien régime ’s principle that no state could survive without a public religion. The new French religion, they decided, would be philanthropic Deism. In devising its liturgy, they followed at first the example of Paris, whose festival of Reason featured, as we have seen, the enthronement of a young girl as goddess of Reason. So innumerable young girls decked out as Reason or Liberty or Nature led processions through innumerable towns to altars erected to the new religion.

However, Robespierre found the worship of reason too close to atheism for comfort and preferred something a little closer to Christianity: his cult of the Supreme Being. And he succeeded in carrying a motion in the Convention, on May 7, 1793, which dedicated France to this cult. He envisaged it as a religion that would be all-embracing and would gather Catholics and Protestants around the same altar. It would have only one dogma (the immortality of the soul) and only one precept (do your duty as a man).

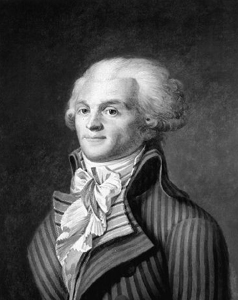

Maximilien de Robespierre (1758–94). Anonymous, eighteenth century. Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris. © Giraudon/Art Resource, New York.

His new liturgy was inaugurated on a beautiful day in June 1794, with himself as high priest: Dressed in a sky-blue coat, his hair carefully powdered, he led a procession from the Tuileries bearing a bouquet of berries, grain, and flowers. The people sang republican hymns, and after a sermon, Robespierre ignited an artfully made cardboard figure labeled Atheism; it crumpled, and then out of its ashes stepped another figure representing Wisdom.

Robespierre himself crumpled shortly afterward, and with him his cult of the Supreme Being. For a time a number of revolutionary and Deistic cults vied with each other for public favor, one of the most successful called Theophilanthropy and influenced by the ideas of Rousseau. But none of them lasted. In spite of curious imitations of Catholic practice, such as the altar to Marat, the republican sign of the cross, or feasts in honor of revolutionary events, they were all too vague and abstract to catch the imagination of a largely illiterate populace. A momentary delight might be taken in a “Republican Lord’s Prayer” with its petition: “Give us this day our daily bread, in spite of the vain attempts of Pitt, the Cobourgs, and all the tyrants of the Coalition to starve us out,” but the novelty soon wore off and the homilies of the local politicians proved a stifling bore. The new religions were never abolished; they just faded away.

Dechristianization itself had spent its force by 1794, and with the decree of February 21, 1795, which guaranteed the free exercise of any religion, there was a rush to open the Churches again.

At the very moment that the Catholic Church in France seemed on the point of revival, the Revolution struck at the person of the Pope himself. This was brought on by Napoleon’s startling Italian campaign of 1796, when he occupied Milan and set up a number of republics in northern Italy on the French model. At first he spared Rome. In the Treaty of Tolentino he recognized the sovereignty of the Pope over the Papal States and only demanded some moderate spoils of victory. But when on December 28, 1797, a corporal of the pontifical guard assassinated a French general, French troops were sent into Rome, and Pius VI was taken prisoner. General Berthier was then ordered by the Directory to remove the Pope to France—away from the Austrians, who might try to rescue him. The rigors of the journey were too much for the eighty-one-year-old Pontiff, and he expired at Valence.

The conclave for the election of the next Pope opened on November 30, 1799, at Venice, under the protection of the Emperor of Austria because of the great political instability at Rome. A compromise candidate, the Benedictine bishop of Imola, Chiaramonti, was chosen after a long and wearisome conclave. It proved to be a happy choice, for the new Pope, Pius VII, proved to have just the right combination of qualities to meet the crisis in the Church.

While the conclave was in progress, Napoleon had again moved his troops into Italy, and a few months later, on June 14, 1800, he decisively defeated the Austrians at Marengo and made himself master of Italy.

The future of the Church in a worldly sense now seemed to hinge on the intentions of this strange genius who had vaulted into power over France—a country whose continuing revolutionary élan made her the most powerful state in Europe. He liked to think of himself as the heir of all that was “reasonable, legitimate, and European in the revolutionary movement,” in Goethe’s phrase—and in fact, Napoleon’s Code did embody the essential elements of the Revolutionary program by its affirmation of the equality of all citizens before the law, the right of the individual to choose his profession, the supremacy of the lay state, and a regime of tolerance for all religious beliefs. On the other hand, by his willingness to curtail individual liberty in the interests of government and by his own autocratic policies, he foreshadowed the reactionary attitude that was to dominate European courts after 1815.

Pope Pius VII (1742–1823) in 1800. Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825). Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles. © Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, New York.

In regard to the Church, Napoleon showed his wonted genius for grasping the complexities of an intricate situation. Religious peace being his goal, he realized that it could not be obtained without recognizing the great power that the Catholic Church still held over the souls of Frenchmen. The bankruptcy of dechristianization was obvious to him, if not to wishful-thinking liberals. But how to heal the now deeply rooted and bitter division between constitutional and nonjuring clergy? This he again realized could only be accomplished by winning over the nonjurors, who were much more numerous and influential than the constitutionals, to accept a settlement along the lines of the earlier Civil Constitution—a maneuver he knew would be impossible without the aid of the Pope. So he told Cardinal Martiniana: “Go to Rome and tell the Holy Father that the First Consul wishes to make him a gift of thirty million Frenchmen.”94

The agreement between Napoleon and the Pope was contained in the Concordat of 1801—the prototype of subsequent nineteenth-century concordats. Its signing was celebrated with fitting pomp at Notre Dame Cathedral on Easter 1802. The First Consul was met at the great west door—like any Bourbon King—by the archbishop, and at the elevation the troops presented for the thirty-two-year-old Corsican general: The Church was recognized “as the religion of the great majority of Frenchmen,” the agonizing schism between the constitutional and nonjuring clergy was ended, and Napoleon had solved one of the most vexing problems he inherited from the Revolution.

The chief points of the Concordat were five: All bishops, both constitutional and nonjuring, had to hand in their resignation to the Pope; the First Consul had the right to name the bishops, and the Pope had the right to institute them canonically; the Church would not seek to recover its alienated property; the clergy would derive their income from salaries paid by the state; and the practice of the Catholic religion would be subject to whatever police regulations were required for the public order.

This last article was in Napoleon’s mind the heart of the Concordat and the means by which he intended to minimize papal control over the French Church and to make it actually as Gallican as in the old regime. He unilaterally attached seventy-seven organic articles to it, which severely limited communications between Rome and the French bishops. He also made the teaching of the Gallican articles of 1682 obligatory in all seminaries.

Subsequent relations of Napoleon with the Pope were stormy. He induced Pius to attend his coronation as Emperor—to dramatize for all Europe the fact that the papacy, which condemned the Revolution, bestowed its blessing on its firstborn successor, the Empire. But he soon learned that the Pope would not be a puppet when Pius refused to compromise the neutrality of the Papal States by joining in a blockade against England, as Napoleon demanded. When the Emperor seized the Papal States, Pius excommunicated him. Napoleon had him arrested (1808) and carried off to France—his captors not even allowing him the time to change his clothes. For nearly six years the Supreme Pontiff had to endure a humiliating captivity. Often he was deprived for long periods of time of counselors and even cut off from all communication with the outside. But he passed his days serenely—like a monk— reading and praying and remaining steadfast in his determination not to yield in matters of principle. He also made good use of his only weapon by refusing to institute any new bishops canonically. By 1814 there were many vacant French dioceses. After Napoleon’s defeats in Russia, with his enemies encircling him, he finally made a virtue of necessity and ordered the Pope restored to Rome. On May 24, 1814, the Holy Father once more entered his city, surrounded by children carrying palms and a wildly applauding crowd.

The consecration of Emperor Napoleon I and the coronation of Empress Josephine in the cathedral of Notre Dame, December 2, 1804. Jacques Louis-David (1748–1825). Louvre, Paris. © Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

The Congress of Vienna (1814–15) brought a general peace to Europe after nearly thirty years of war—a peace that lasted a hundred years. It disavowed the Revolution, restored the old order, put the Bourbons back on the throne of France, and perched Napoleon on a rock two thousand watery miles away. It also restored the Pope as the absolute monarch of the Papal States. But it could not undo the work of the Revolution—the magnitude of social and political transformation was too extensive. France and the rest of Europe could never return permanently to a hierarchical society—held together by an alliance of throne and altar, where status was determined by birth and where monarchs ruled by divine right.

The bitterness, hatred, and enmity aroused by the Revolution would poison the life of France for a long time and create such a fundamental cleavage in French politics that no regime until 1870 was able to maintain itself for more than two decades. Moreover, the schism between a considerable body of Frenchmen and the Church was final; dechristianization as a program failed, but anticlericalism remained as its permanent vestige. The Church lost in large measure its control over the daily life of the people. The process of secularization introduced by the laws of 1794 opened a new chapter, and the secular spirit continued to spread. Civil divorce, civil marriage, and the secular school system were its most visible expressions.

Elsewhere the Catholic Church was also profoundly transformed by the Revolution, and nowhere more dramatically than in Germany. Here the Catholic prince bishops lost their feudal princedoms. And when the reorganization of the Church was carried out at the demise of Napoleon, a large proportion of Catholics were put under Protestant rulers. Church property was taken over and monasteries dismantled. The Church was reduced to an agency of the state; its schools and clergy were supported by the state.

But though the Church suffered grave damage, the effect of the Revolution on the papacy was beneficial—in fact, it helped to create the more powerful papacy of the nineteenth century. The fact that Napoleon and the Pope alone settled the fate of the French Church foreshadowed things to come. And Pius VII greatly enhanced the papal image by his heroic stand against the tyrant. But more fundamental reasons were ultimately responsible. In shattering the ancient monarchies, the Revolution liberated the Church from the servitude to Gallican monarchs and the so-called enlightened despots who placed their creatures on the throne of Peter, co-opted the Catholic missionaries for their colonial aims, and installed puppet bishops in their kingdoms. With the end of the old order the Popes could now make Rome once more the vital center of Catholicism and guide the Church back to its true spiritual mission. Gallicanism was not yet completely dead—many bishops still embodied its spirit—but the clergy would become more and more ultramontane, looking to Rome for leadership, while the overseas missions were to revive under Roman command.