Chapter 31

THE AMERICAN CHURCH

No missionary territory in the nineteenth century registered more sensational gains than the Catholic Church in the United States. Thanks to a massive influx of Catholic immigrants—Irish, German, Italians, Poles, and others—the growth of the Catholic Church far outstripped the nation’s growth. The American bishops were able to successfully integrate these heterogeneous, polyglot newcomers into the Church structure and provide a huge network of schools, hospitals, and other institutions for them that were soon the envy of the Catholic world.

THOSE WHO FIRST planted the Catholic Church in North America—outside the original thirteen colonies but within the present boundaries of the United States—were bands of Jesuit, Franciscan, Capuchin, Recollet, and other missionaries. Moved by tremendous zeal to save the souls of the Native Americans, they suffered every form of hardship, even torture and death, to build their little churches and gather around them the nucleus of a Catholic parish. The Franciscan Junípero Serra and the Jesuit Father Eusebio Kino are the most famous of the hundreds of priests who evangelized the Native Americans in the vast Spanish territory stretching from Florida to California. They taught them the arts of civilization as well, and left souvenirs of their labors in names like San Francisco, San Antonio, and Los Angeles.

Northward lay the huge French area, which also drew many Catholic missionaries, Jesuit, Capuchin, Recollet, and others. The Jesuit Père Jacques Marquette, discoverer of the Mississippi, and the Jesuit martyrs Isaac Jogues, Jean de Brébeuf, and their companions were among the many who ministered to the spiritual and temporal needs of the Hurons and other Indian tribes. The missionaries also helped establish French Catholic outposts on the Great Lakes and down through the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, a chapter in Catholic history that is recalled by names like Detroit, St. Louis, Vincennes, Louisville, and Marietta.

Within the thirteen English colonies, Catholics faced a different type of situation. Like the Puritans and Quakers, the English Catholics had come to America to escape persecution. The opportunity to do so was afforded them by their coreligionists, George Calvert, the first Baron of Baltimore, and his brother Leonard, who founded Maryland as a haven for persecuted Christians. At first the colony hewed to the Calverts’ ideal, and Catholics and Protestants lived peacefully side by side in a spirit of mutual toleration that was embodied in the famous Act of Toleration of 1649. But when political predominance passed to the Protestants in Maryland, Catholics were subjected to severe restrictions on their religious liberty. The only other colony where Catholics were found in any significant number before the Revolution was Pennsylvania, where the liberal policy of the Quakers encouraged Catholics to settle.

The American Revolution brought about a big change in the fortunes of American Catholics. The legal disabilities under which they labored were gradually lifted, beginning with Maryland’s and Pennsylvania’s adoption of religious liberty in 1776.

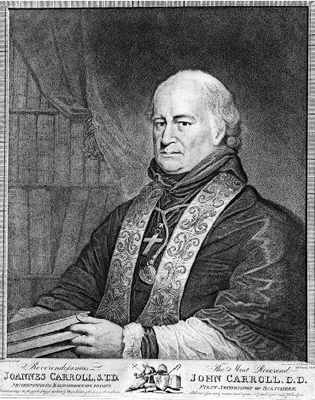

Until the Revolution, Catholics in the colonies were under the rule of a vicar apostolic resident in London. But with the advent of American independence and the more favorable climate for Catholics in the United States, Rome felt it was time for them to have a bishop of their own. The man chosen was John Carroll.

The American Church was singularly fortunate in this man chosen to guide its destiny and to lay the groundwork for its future expansion. As head of the American Catholic missions, John Carroll had already proven to be a wise and humane superior, and his priests showed their feelings about him when in 1789 they elected him the first American bishop by a nearly unanimous vote (twenty-four to two). He came from an old and distinguished Maryland family. One of his cousins, Charles, signed the Declaration of Independence, while his brother Daniel was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. A Jesuit until the order’s suppression in 1773, John Carroll was a highly educated scholar and a man of broad vision and genuine spirituality, totally dedicated to the arduous task that lay before him.

John Carroll (1735–1815), first Roman Catholic bishop in the United States, in 1812. Engraving by William Satchwell Leney (1769–1831) and Benjamin Tanner (1775–1848). Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. © National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, New York.

In building the institutions necessary for the growth of the Church he received much assistance from the various religious communities of men and women who began entering the States during his tenure. The first to arrive were four cloistered Carmelite nuns, who opened a contemplative convent in 1790. A few years later three Poor Clare nuns founded a school for girls at Georgetown, which shortly afterward was taken over by the first group of Visitation nuns who came to the United States. The first native sisterhood, the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph, was founded by Elizabeth Seton (canonized in 1975) at Emmitsburg, Maryland, in 1809, and they opened Catholic elementary and secondary schools in a number of communities.

Male religious orders also played an important role in laying the foundations of Catholic institutional life in the United States. Four French Sulpicians came in 1791 and opened the first seminary, St. Mary’s, in Baltimore. And when the Jesuit order was re-established in the United States in 1806, members of this order took over Georgetown College. The first Augustinian, Matthew Carr, arrived in 1795, while the Dominicans began their history here when Edward Fenwick, later first bishop of Cincinnati, and several companions inaugurated the first American Dominican house at St. Rose Priory near Springfield, Kentucky, in 1805. Many other religious communities eventually settled in the United States, and together with various native ones played an immense role in building the Church in the United States.

A problem that was to haunt the American bishops for many decades surfaced during Carroll’s administration: the attempt by laymen to get control of the property of the Church and to arrogate to themselves the right to choose their own pastors and dominate Church affairs. Carroll had only limited success in dealing with this problem, but in other respects he was more fortunate. He saw his little flock, which at his consecration in 1790 numbered some 35,000 (out of 4 million Americans), grow to nearly 200,000 by his death in 1815. His diocese was subdivided in 1808, when four other dioceses were added: Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Bardstown (later Louisville).

While thoroughly loyal to Rome, Carroll was also thoroughly American, enthusiastically and profoundly committed to its basic principle of separation of Church and state. He stamped this positive attitude toward the American system indelibly on the mentality of American Catholics, who in this sense at least remained consistently in the liberal Catholic camp.

The Age of Carroll was followed by the Age of John England, first bishop of Charleston and for over twenty years the most powerful voice in the American hierarchy. John England was very much alive to the possibilities for the Catholic Church in the new land, and he earned an early grave for himself by his unremitting toil in behalf of the Church. No American bishop was more anxious than John England to break down the walls of prejudice that kept his fellow Americans from a true understanding of the Catholic Church. He jumped at any chance to speak before non-Catholic audiences, and his reputation as a speaker put him somewhere in the galaxy of Webster and Calhoun. His two-hour address before the United States Congress was undoubtedly the greatest triumph of his career. Extremely conscious of the need to adapt the Catholic Church to the American spirit, he set up a system of ecclesiastical government that enabled the clergy and laity to participate in formulating diocesan policy. As an exercise in democracy it was unfortunately too far ahead of its time to survive when England died in 1842.

Not the least of John England’s contributions to the American Church was his insistence that the archbishop of Baltimore gather the American bishops together in council. England’s advice finally prevailed, and the subsequent councils held at Baltimore from 1829 to 1884 (seven provincial and three plenary councils) represented the most persistent and successful exercise in collegiality carried on by any group of Catholic bishops during the nineteenth century. Led by a number of remarkable prelates—besides England himself, men like the scholarly Francis Patrick Kenrick, bishop of Philadelphia; Martin Spalding, archbishop of Baltimore; John Hughes, archbishop of New York; John Purcell, archbishop of Cincinnati, and frontier bishops like Simon Bruté and Benedict Flaget—the bishops steered the burgeoning young American Church through crisis after crisis.

Under their able leadership, new dioceses proliferated as the Catholic Church kept pace with the rapid westward movement of the American frontier. By the time of the fourth provincial council in 1840, the archiepiscopal see of Baltimore presided over fifteen suffragan sees: Boston (1808), New York (1808), Philadelphia (1808), Bardstown (1808), Charleston (1820), Richmond (1820), Cincinnati (1821), St. Louis (1826), New Orleans (1826), Mobile (1829), Detroit (1833), Vincennes, (1834), Dubuque (1837), Nashville (1837), and Natchez (1837). Nowhere in the Catholic world was the spread of the Church so impressive, as each council at Baltimore marked another step forward in organizational expansion. When we come to the first Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1852, we find six provinces now organized: Baltimore, Oregon City, St. Louis, New York, Cincinnati, and New Orleans, each with an archbishop, and under these provinces were ranged twenty-six suffragan sees. By the time of the third plenary council in 1884, the number of archiepiscopal sees had increased to eleven, Boston, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Santa Fe, and Chicago having been added, while the number of dioceses had increased to fifty-four.

In their work at the councils in Baltimore, the bishops were obliged to adhere to the norms laid down by the Council of Trent (1545–63), and they were concerned with applying Trent’s decrees to the particular circumstances of the American Church. In doing so they ranged over a multitude of concerns. They prescribed the proper rites for the administration of the sacraments, determined the age of confirmation, laid down rules for the reverent giving of Holy Eucharist to the sick, determined qualifications for Catholic burial, discountenanced funeral orations, fixed the amount of the stipend offering for Mass, ordered confessionals to be erected, and laid down the conditions for conferring plenary indulgences. Recognizing the importance of marriage, they commanded marriages to be celebrated in the parishes of one of the couples marrying, and they warned Catholics against mixed marriages while requiring a pledge from the non-Catholic party in a mixed marriage to allow the children to be brought up Catholic. They tried to regulate the daily life of the priest in minute detail, down to such particulars as his mode of dress (making the Roman collar obligatory in 1884), his type of recreation (forbidding him to attend theaters or horse races), and the furnishings of his rectory. They showed an increasing concern about the dangers to the faith of Catholic children attending public schools and gradually forged the policy that led to making parish schools mandatory in 1884.

The uniform system of discipline enacted by the bishops at Baltimore was a magnificent achievement and laid a solid foundation for the Catholic Church in the United States.

One of their most pressing concerns was the constant influx of immigrants, who persistently swelled their congregations. This flood began in the 1820s, with the first wave of Irish immigrants. Largely because of Irish immigrants, the number of Catholics jumped from about 500,000 (out of a U.S. population of 12 million) in 1830 to 3,103,000 in 1860 (out of a U.S. population of 31.5 million)—an increase of over 800 per cent—with the number of priests and the number of churches increasing proportionately. So large was this increase that by 1850 Roman Catholicism, which at the birth of the nation was nearly invisible in terms of numbers, had now become the country’s largest religious denomination.

The next era, 1860 to 1890, was equally impressive, as the growth of the Church far outstripped the growth of the national population, the Church tripling in size while the nation was only doubling. By 1890 Catholics numbered 8,909,000 out of the nation’s 62,947,000. German Catholics, who were previously far less in number, now began nearly to equal the number of Irish immigrants. The wave of immigration, lasting from 1890 to the immigration laws of the 1920s, brought a preponderance of Italians and eastern Europeans. Over a million Italians alone came during the two decades from 1890 to 1910.

The reaction of the ordinary American to this invasion of Catholics was understandably one of concern. He did not relish the prospect of being in-undated by people whose habits, customs, and religious practices appeared foreign and threatening. Sometimes these vague fears were exploited by unscrupulous demagogues, and mobs would vent their wrath on the nearest Catholic institutions. One of the most conspicuous of such episodes occurred in 1834 after the appearance of a series of books and pamphlets vilifying the Church and depicting nuns and priests as hypocritical demons of lust and greed. The Reverend Lyman Beecher stirred up a mob that proceeded to burn down a convent and school conducted by Ursuline nuns at Charlestown, Massachusetts. In the ensuing years “No Popery” gangs burned some Catholic churches and lynched a number of Catholics. In the 1850s the Know Nothings succeeded the Nativists. The Civil War and its aftermath distracted the “No Popery” advocates, but the movement flared up again when the American Protective Association was organized in 1887. Its members swore never to vote for a Catholic and never to hire one or go on strike with one if at all possible. Anti-Catholic feeling was still strong enough as late as the 1920s to enable the Church’s enemies to pass the Immigration Restriction Laws of the 1920s. Anti-Catholic sentiment also figured in the activities of the Anti-Saloon League of the 1920s and the campaign against Al Smith, the first Catholic of a major party to run for the presidency.

In order to survive in such hostile surroundings, the American Catholic Church naturally developed a defensive and aloof attitude, turning inward on itself and devoting its best energies to building up a little world of its own that would provide an alternative to the culture dominated by the Protestants. Central to this scheme of things was the parish school. To understand the origins of the Catholic parochial school system we must remember that the first big wave of Catholic immigrants coincided with the spread of the public school system in this country. But when Catholics entered their children in these public schools they soon found the Protestant atmosphere of the public school a detriment to their children’s Catholic faith. In the New York schools, for instance, the Protestant version of the Bible was the only one allowed, and when Bishop Hughes protested, he met with an angry rebuff. So the bishops at Baltimore gradually became more insistent on the need for Catholics to build and operate their own schools. As a model they turned to the type of school opened by Elizabeth Seton and her Sisters of Charity at Emmitsburg, Maryland, in 1810. By 1840 there were at least two hundred of these parochial schools in operation, half of them west of the Alleghenies. They formed the nucleus of what was to become the largest system of private schools in the world. The biggest turning point in their expansion occurred when the third plenary council at Baltimore in 1884 decreed that every parish should have a school.

Besides the parish school, the bishops found it necessary to establish many other types of institutions in order to protect their flock from the contaminating influences of a Protestant and secular society. What was to become a huge network of orphanages, hospitals, old-age homes, etc., began in October 1814, when three of Mother Seton’s Sisters of Charity opened the first Catholic orphanage in Philadelphia. Fourteen years later the same order of nuns opened the first American Catholic hospital in the same city; it was the forerunner of some nine hundred such institutions that now exist in the United States. Another means found most effective in safeguarding the faith of the faithful and molding them into a loyal body was the Catholic press. Here as in other fields it was the imaginative John England who led the way in 1822, with his United States Catholic Miscellany, the first American weekly Catholic newspaper. The idea quickly caught on, and many other dioceses could soon boast of a weekly journal, though few of them could rival the intellectual content of England’s paper.

The number of German Catholic immigrants began to increase rapidly during the 1840s and 1850s, and in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, surpassed the number of Irish Catholic immigrants. The Germans naturally wanted their own parishes where they could hear sermons in German, confess in German, and have their children instructed in German, a parish where they could also preserve their own religious customs. To meet these needs a German national parish, St. Nicholas, was organized in New York City in 1833. As the number of German immigrants grew, these German parishes multiplied especially in the Midwest, where a high concentration of German immigrants were found in the so-called German triangle formed by Milwaukee, Cincinnati, and St. Louis. The German parish exhibited a distinctive character as its members took a special pride in maintaining their Old World customs and were much devoted to pomp and ceremony and elaborate musical programs as a feature of their liturgy. They also often indulged their fondness for processions when their many different parish societies took part, each marching under their own banner to the strains of a military band.

Conflict between the German element in the American Church and the Irish, who dominated the American hierarchy, was an old story by the 1880s. Many parish chronicles told how the two groups often bickered over a host of issues. But in the 1880s and 1890s the antagonism between Irish and Germans was intensified for various reasons and turned into a crisis of major proportions for the burgeoning American Church.

The crisis began when a number of prelates of outstanding ability began calling for an end to the separatism and aloofness of American Catholics and urged them to move into the mainstream of American life. Foremost among those calling for a thoroughgoing Americanization of the Catholic Church in the United States were Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul; Monsignor Denis O’Connell, rector of the American College in Rome; Bishop John Keane, first rector of Catholic University of America; and John Lancaster Spalding, ordinary of Peoria. Their aims were similar to the liberal Catholics in Europe insofar as they shared their desire to reconcile the Church with modern culture. Like the European liberal Catholics, they were optimistic about the direction taken by modern political and intellectual movements and wanted the Church to adjust its traditional positions in order to endorse political democracy, modern scientific methods of research, efforts at social reform, and ecumenism. The most powerful advocate of Americanization, Ireland was inspired by his experience on the American frontier to believe that the United States was ripe for conversion if the Church could only shake off its foreign image. With his friends in the hierarchy, backed by most of the Irish clergy in the Midwest and West and by his favorite religious congregation, the Paulists, as well as most of the faculty at the Catholic University of America, he orchestrated a campaign to demonstrate the profound agreement of Catholic aspirations with the aspirations of the American people. Endowed with tremendous vitality and enormous oratorical talent, Ireland stirred up a controversy that shook the American Church to its foundations.

His main adversaries were the German Catholics, who in these decades were pouring into America in great numbers. Attached as they were to their Old World traditions and language, they instinctively rejected Ireland’s plea to Americanize. Moreover, they had long-standing positive grievances against the Irish-dominated hierarchy. They wanted more bishops of German extraction and more independent German parishes. Their attempts to sway Rome along these lines, however, were frustrated by Ireland’s ability to outmaneuver them in the Curia. A furious storm broke when a German Catholic layman, Peter Paul Cahensly, backed by various European Catholic organizations, presented a memorial (the Lucerne Memorial) to Pope Leo XIII in 1891. It sketched a dark picture of the plight of German Catholics in the United States and called for remedies, including more bishops of German background in the United States hierarchy and more separate German parishes. The Americanist bishops were deeply disturbed by this intrusion of the outsider, Cahensly, into their affairs and succeeded in convincing Rome that Cahensly’s plan would divide the hierarchy into antagonistic nationalist blocs and fragment the American Church into separate ethnic ghettos. Ireland’s victory, however, only hardened the German Catholics all the more against his program of Americanization.

No words of Ireland’s incensed the German Catholics more than his address to the National Education Association at St. Paul in 1890, when he delivered a glowing hymn of praise to the public school system, spoke of the Catholic schools as an unfortunate necessity, and proposed a compromise that would allow Catholic schools to be run as public schools during regular school hours and only used after hours for religious instruction. (Rome eventually gave grudging approval to Ireland’s alternative but at the same time encouraged the Catholic bishops to continue building a separate Catholic school system.)

The school issue definitely crystallized the anti-Ireland forces into a large coalition made up of the mass of German Catholics, the Jesuits, and some potent allies among the Irish Catholics, principally Archbishop Corrigan of New York and his suffragan Bishop McQuaid of Rochester, who were generally unsympathetic to Ireland’s liberal ideas and found his blustering personality offensive. The newly founded American Ecclesiastical Review acted as one of the main organs of this faction, and it often aimed its fire at the Paulist Catholic World. Another strong voice on the German side was Monsignor Joseph Schroeder, professor of dogmatic theology at the University, an imported continental scholar who attacked the ideology of the liberals.

The differences between the two forces were compounded by other divisive issues. The progressives wanted Catholics to get involved in movements for social reform and, when necessary, even to join with non-Catholics in various societies whose aim was social betterment. The conservatives opposed Catholic participation in such societies, especially if they involved a secret, oath-taking ceremony, as many of them did. The conservatives could point to the Church’s prohibition of Catholic participation in the Masons as an indication of the Church’s general attitude toward secret societies, and for this reason the conservatives opposed Catholic participation in the Knights of Labor, the largest labor organization of the day, and they wanted Rome to condemn the Knights. But Cardinal Gibbons, who generally favored the progressive point of view, succeeded with the help of Ireland and Keane in dissuading Rome from such a move. But the progressives were not able to keep Rome from condemning Catholic membership in other secret societies, such as the Odd Fellows and the Knights of Pythias.

Another focal point of controversy was Catholic University of America. As the brainchild of John Spalding, and with Keane as its first rector when it opened in 1889, it quickly became the stronghold of the progressives, who hoped it would provide a Louvain-style intellectual atmosphere in training leaders for the American Church. But the fledgling school drew constant fire from the conservatives and for a long time had great difficulty measuring up to its founders’ expectations.

As the debate became increasingly acrimonious, Pope Leo became seriously worried lest the American Church tear itself apart. He decided to step in, and in October of 1892 he sent Archbishop Francesco Satolli to become his first apostolic delegate to the American Church with the hope that Satolli would be able to heal the breach between the two factions. This plan misfired, however, when Satolli was rebuffed by Corrigan and taken in tow by Ireland and Keane.

At this point the conservatives sharpened up their strategy—basically the old idea that the best defense is a good offense. Led by Monsignor Schroeder, they began to harp on the theme that the Americanizers were guilty of the false liberalism already condemned in the Syllabus of Errors as well as being tainted by doctrinal minimalism and antipapal tendencies. The progressives played into their hands by participating in the World Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in September 1893. Bishop Keane delivered a speech for Cardinal Gibbons, who was ill, and delivered several other papers.

Whether Satolli really believed the progressives guilty of false liberalism as charged, it is difficult to say, but the fact is that he did begin to distance himself from the progressives while showing evident signs of favor toward the conservatives. Several blows suffered by the liberals showed which way the wind was blowing. Monsignor O’Connell was removed from his post at North American College in 1895 and Keane from his at the University.

The din of the American controversy reached to Europe, and it was there that the final decisive battle was fought. Ireland had stirred up great interest in his ideas when he barnstormed France in 1892 and was warmly toasted as a symbol of American democracy. The French liberal Catholics hoped that he might have some influence on their royalist fellow Catholics and help to change their negative attitude toward democracy and social reform.

Ireland’s visit stirred up some debate in the French Church, but the whole affair was pretty well forgotten until a book appeared, Le Père Hecker Fondateurdes “Paulistes” Américains, 1819–1888, that celebrated the leading ideas of Ireland and the Americanizers. This was a French translation of an American biography of Father Isaac Hecker, edited with a preface by Abbé Klein, a French priest and stanch admirer of Ireland and containing an introduction by Ireland himself. Hecker was one of the most notable of the converts to the American Catholic Church in the nineteenth century. After entering the Church in 1844, he joined the Redemptorists and was ordained in 1849. After some difficulties with his superiors, he left the community and founded his own order, the Paulists. It was at this point that he began to develop his very personal ideas on how the Church must adapt to the American mentality if it wanted to make any real progress in converting Americans. Hecker had considerable influence on the American liberal Catholics. In his preface to the French edition of Hecker’s life, Ireland extolled the convert priest as one predestined to teach the Catholic Church how to adjust to the modern spirit of freedom and democracy.

The book was widely acclaimed and aroused considerable interest. And a strong body of opinion hostile to the book was soon formed: Hecker’s main ideas were labeled “Americanism” and denounced as the same heretical liberalism condemned by the Syllabus of Errors. The attack on Hecker broadened out to a general attack on the ideas of Ireland and the Americanizers. A whole stream of books and articles appeared in France accusing the Americanists of propagating erroneous opinions about the role of authority in the Church, of favoring the natural over the supernatural virtues, and of weakening the dogmas of the Church.

In time Pope Leo felt compelled to step in. When rumor spread that the Pope was about to condemn Americanism, Ireland rushed to Rome and Gibbons cabled a protest. But they were too late. The Pope’s letter to Gibbons, Testem Benevolentiae, appeared in early February 1899. It took note of the view that some ideas and tendencies labeled “Americanism” were circulating in the Church: namely, false ideas about adapting the Church to modern ideas of freedom and authority, a tendency to esteem the so-called natural and active virtues over the passive and supernatural ones, and finally a rejection of external spiritual direction in favor of interior guidance by the Holy Spirit. If this is what people meant by Americanism, the Pope said, then Americanism was to be condemned. While the encyclical mentioned no names, it was obvious that the letter was aimed at the liberal Catholic camp. While he privately bemoaned the Pope’s letter, Ireland publicly displayed a nonchalant attitude and denied that he or any of his friends ever held the ideas condemned by the Pope. The Pope’s letter did usher in a period of relative peace in the American Church, as German and Irish calmed down. Nobody changed sides as a result of Testem. The Americanists continued to hope for changes that now seemed most remote, while their opponents continued to work against them. The Catholic Church in the United States remained authoritarian and entrenched in its ghetto.

One of the concerns of Ireland and his followers was to change the attitude of their fellow Catholics toward social reform, an attitude that was extremely conservative. Catholics were urged customarily to practice individual acts of charity and the traditional corporal works of mercy, and they were taught that spiritual reform, not social change, was what really mattered.

It was not until the mid-1880s that the progressive Catholics began to take an interest in such questions as trade unionism and justice for the poor, but these questions remained secondary in the Church during the decades of controversy over Americanism. While many Protestants tried to explore the social implications of the Gospel, Catholics expended their energies mainly in the quarrel between German and Irish Catholics. However, as an urban Church composed mainly of working people, the Catholic Church remained in close touch with the problems of labor at the grassroots level and veered naturally to the side of labor during the harsh industrial disturbances associated with such names as Homestead, Pullman, and the Haymarket. Pope Leo’s encyclical Rerum Novarum helped to quicken American Catholic sympathies with the cause of labor, and gradually a number of leaders came forward to educate the Church on its responsibilities in bringing about social reform. Outstanding among them were two priests, Peter Dietz (d. 1947) and John A. Ryan (d. 1945). Dietz worked with Catholic members of the AFL and opened a social service school in Cincinnati. It inculcated in its hundreds of graduates the necessity of systematic, organized effort if the Church’s impact on social reform was to be effective. The demise of his school in 1923 at the hands of Archbishop Moeller and some conservative Republicans of Cincinnati was a big setback for social Catholicism in the United States.

John A. Ryan came to national prominence and began his forty years of tireless efforts to arouse the Catholic social conscience with his book A LivingWage (1906). It was not, however, until the hierarchy began to move as a body that Catholic social action began to exert significant influence on the nation’s life. This involvement of the hierarchy in social issues dates back to World War I, when the National Catholic War Council was founded to coordinate the Catholic contribution to the war effort. Out of the council came a permanent organization, the National Catholic Welfare Conference, a peacetime coordinating agency for Catholic affairs. Its eight departments included one devoted to social action, which under its director, John A. Ryan, turned its attention to the pressing social problems of the United States.

It immediately displayed the liberal thrust it has maintained over the years in its first major statement: a document drawn up by Ryan and issued as the bishops’ pastoral for 1919. Popularly known as the Bishops’ Program, it became more widely known than any of the other sixty or so postwar proposals for social reconstruction. It called for legislation to guarantee the right of workers to bargain collectively, a minimum-wage act, social security, and health and unemployment insurance. Though denounced in the New York State legislature as socialistic, it proved astonishingly on target: All but one of the proposals were later incorporated into the New Deal legislation of the thirties. In the meantime, however, Catholic social actionists had to pass through the discouraging twenties, when America retreated from its historic commitment to securing greater liberty and justice for all.

There were definite signs of an awakened Catholic social consciousness as the nation moved into the thirties. And most Catholics welcomed the New Deal as a consonant with their vision of social justice as most recently explicated in Pope Pius XI’s encyclical Quadragesimo Anno of 1931. No Catholic was more enthusiastic about the New Deal than John A. Ryan, who was generally recognized by this time as the leading Catholic spokesman on social issues. For his multitude of admirers, Ryan’s scholarly and measured words seemed to combine the best of social Catholicism with the best in the American progressive tradition. Ryan’s was the most persistent Catholic voice among those calling for strong government action to promote a humane social order, and he exercised a tremendous influence in moving Catholics to a positive understanding of their social responsibilities.

In sharp contrast with Ryan’s scholarly endeavors to educate American Catholics stood the performance of the sensational and demagogic Charles Coughlin, the radio priest of Royal Oak, Michigan. The immense size of the audience that listened in on his Sunday afternoon broadcasts testified to his uncanny talent for articulating the fears and suspicions of millions of Americans, both Catholics and otherwise, who felt victimized by the Depression. Coughlin drew on Scripture, the papal social encyclicals, and American populist and even radical literature in excoriating the legions of enemies he found responsible for the plight of the poor and wretched. At the peak of his power in 1936 he felt strong enough to challenge Roosevelt himself—a move that proved disastrous—and Coughlin’s influence began to wane. He also alienated many of his former supporters by his hysterical anti-Semitic tirades, his fascistic tendencies, and his opposition to America’s entry into the war until he was eventually silenced by Archbishop Mooney of Detroit. While no one did more than Coughlin to dramatize the fact that the Catholic Church was concerned with social justice, his contribution otherwise to American social Catholicism was small.

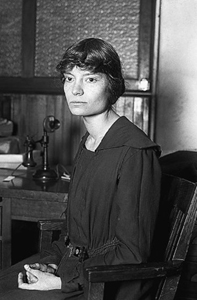

Consistently opposed to Coughlin were the members of the Catholic Worker Movement founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin. Their aim was to identify as completely as possible with the poor and downtrodden. With this in mind, Dorothy opened a House of Hospitality in the New York Bowery in 1933, the first of many that spread around the country. They offered a warm welcome and a warm meal to the homeless, unemployed, and hungry. These houses drew together a large number of apostolic and socially conscious young Catholics who practiced voluntary poverty and acted as effective propagandists of the Church’s social doctrine by applying papal social teaching in a wide variety of social action. Their paper, the Catholic Worker, was devoted to the cause of labor and soon reached a circulation of one hundred thousand. The Catholic Workers protested against the impersonal, mechanistic character of a technological society and stressed one’s personal responsibility for injustice. They formed small communities of persons committed to living in solidarity with the afflicted and suffering while devoting themselves to prayer and frequent reception of the sacraments. Unlike most social Catholics, the Catholic Workers did not hesitate to point out the tremendous failures of the American system, its materialism, racism, and imperialism. As pacifists, they condemned America’s entry into World War II and in consequence lost much of their support. But they played a prophetic role in the Church. By challenging the prevailing narrow Catholic mentality that equated morality with opposition to indecent movies and birth control, they helped many of their coreligionists to adopt a more profound view of social reconstruction.

Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, in 1933. © Bettmann/Corbis.

The advent of mass unionism in the United States with the formation of the CIO in 1935 stirred interest among Catholics in the social encyclicals, and a sizable number of priests began to educate themselves in industrial problems. A new type of priest appeared, the labor priest, who picketed with the workers and set up schools in order to instruct labor organizers in the basics of Catholic social doctrine. Eventually there were more than a hundred of these labor schools, where priests acted as advisers to Catholic members of the big unions in their struggle against Communist infiltration, racketeering, and union bossism. But in spite of the work of the labor priest, and in spite of the high percentage of Catholics in the ranks of organized labor, Catholic thought, as the historian David O’Brien says, exerted little influence on labor’s development.119

One issue of social justice that remained largely ignored by the Church in the 1930s was racial prejudice. Until the end of World War II, Catholics conformed to the general practice of Americans in segregating their schools and churches. Few Catholic voices were raised in protest, although Father John LaFarge, S.J., and the Catholic Interracial Council, which he helped to found, worked heroically to change Catholic attitudes. It was only after the war, however, that a number of Catholic bishops, led by Archbishop Rummel of New Orleans, Cardinal Meyer of Chicago, Cardinal O’Boyle of Washington, Cardinal Ritter of St. Louis, Archbishop Lucey of San Antonio, and Bishop Waters of Raleigh, North Carolina, began to desegregate their schools and churches and urge their people to change their attitudes. Many of the clergy began in earnest to fight racial prejudice and discrimination, but it proved immensely difficult to arouse the conscience of the average Catholic, priest or layman, on this score.

The immigration restriction laws of the 1920s brought an end to the massive and constant increase of the Church’s numbers. Henceforth its rate of growth followed basically the same curve as that of the Protestant Churches. In 1950, for instance, Protestants constituted 33.8 per cent of the population, and Catholics, 18.9 per cent. By 1958 the Protestant percentage had increased to 35.5 and the Catholic to 20.8. Organizationally the Church in the United States continued its remarkable progress: Metropolitan sees were erected at San Antonio (1926), Los Angeles (1936), Detroit, Louisville, and Newark (1937), Washington (1939), Denver (1941), Indianapolis (1944), Omaha (1945), Seattle (1951), and Kansas City, Kansas (1952), while a number of American bishops were made cardinals: Dennis Dougherty of Philadelphia (1921), George Mundelein of Chicago and Patrick Hayes of New York (1924), Samuel Stritch of Chicago, Francis Spellman of New York, Edward Mooney of Detroit, and John Glennon of St. Louis (1946), James McIntyre of Los Angeles (1953), John O’Hara of Philadelphia and Richard Cushing of Boston (1958), and Albert Meyer of Chicago and Aloisius Muench of Fargo (1959).

Catholics continued to pour their best energies and resources into the educational effort. By 1954 there were 9,279 elementary schools enrolling 3,235,251 pupils, 2,296 secondary schools with 623,751 students, 224 colleges with over 280,000 students, and 294 seminaries with 29,578 students.

One sign, perhaps, of growing spiritual maturity among American Catholics was the great increase in vocations in the contemplative life. After World War II hundreds of young men began filling up the contemplative, mainly Trappist, monasteries scattered around the country. This influx was due in part to the widespread influence of a convert, Thomas Merton, whose autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, provided a fascinating account of the spiritual odyssey that led him into the Trappists.

By the 1950s it was quite obvious to most observers that the Catholic Church in the United States had become a thoroughly American institution. The era of Protestant dominance was over. The political significance of this fact was underscored when John F. Kennedy was elected the first Catholic President of the United States, an event that coupled with the reign of Pope John and the calling of his council definitely marked the beginning of a new era in the history of American Catholicism.