Chapter 33

THE RESURGENT LIBERAL CATHOLICS RING DOWN THE CURTAIN ON THE POST-TRENT CHURCH AT THE SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL

John XXIII announced his intention of calling an ecumenical council at the ancient Roman basilica of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls on January 25, 1959, which would have as its task to promote the unity of all Christian peoples.

John attributed his idea simply to an inspiration of the Holy Spirit. Another way of putting it would be that the council was John’s solution to a problem that was beginning to preoccupy thoughtful Catholics everywhere: How could an ancient Church that prided itself on being unchangeable and antimodern survive in a world undergoing social, political, and cultural transformations of unprecedented magnitude?

By the year 1959, in fact, the world and Europe seemed on the threshold of an entirely new era. In the short space of fifty or so years, profound scientific, technological, cultural, and social developments had so changed the conditions of life that one felt separated from the previous four hundred years by a wide gap. A term had even been coined—“post-modern”—to describe this sense of living in a new historical period.

To single out any one factor responsible would seem quite arbitrary, but many historians would agree that scientific and technological developments should be listed first in the order of importance. Just to single out the most important in a continuing stream of inventions would consume too much space here. Many of them, like electricity, the internal-combustion engine, the telephone, telegraphy, the microphone, the camera, the record player, the bicycle, and the typewriter had already made their appearance before 1900, but it took more time for them to be fully exploited. And in most cases it was only after World War I that their full impact was felt. Other epoch-making inventions—alloy steels and aluminum, synthetic rubber, plastics, and artificial fabrics like nylon—have radically changed the material basis of society.

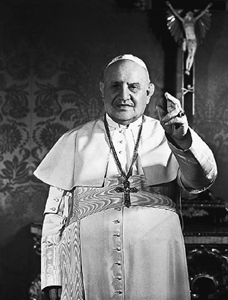

Pope John XXIII gives the benediction. © Bettmann/ Corbis.

Technology also revolutionized modes of communication and transportation: The automobile, the airplane, radio, movies in color and sound, and television have ushered man into the era of the global village.

So it was to a world swept by hurricane winds of change that news came of John’s decision to call an ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The announcement struck the Roman Curia like a thunderbolt. The word “council” sounded too much like “revolution”: Only the Lord could predict what three thousand bishops might do if they got out of hand. And so they girded themselves for battle. Their strategy was clear. Evidence indicates they intended to secure control of the council and make sure they kept control. At first they succeeded. Curial officials monopolized the key positions on the preparatory commissions that drew up the proposals or schemata. After sifting through thousands of suggestions sent in by the bishops of the world, they drew up seventy proposals or schemata to be submitted to the council. These ranged over a bewildering variety of subjects—revelation, ecclesiastical benefices, spiritualism, reincarnation, etc.—and were larded with the traditional denunciations and anathemas. If all went as planned, the Curia expected the bishops simply to put their stamp of approval on them and return home. The council would then slip into the past and be remembered only as another glorious Roman pageant.

It was an open question in the minds of astute observers whether this Curial strategy would succeed when the council opened on October 11, 1962. The occasion was marked by ceremonies of dazzling brilliance, an endless procession of bishops vested in flowing white damask copes and miters moved majestically past the towering obelisk of the Bernini piazza and up the broad steps into St. Peter’s basilica. As the Pope entered—borne aloft on his portable throne—he was greeted with a huge burst of sound as the organ boomed and applause roared from the assembly. Dismounting, he made his way between the tiers stacked with bishops stretching the entire length of the nave, and reaching his place at the twisted bronze canopy, he turned toward the bishops and intoned the opening liturgy.

At its conclusion five hours later, John mounted the rostrum and delivered one of the most remarkable papal addresses in the entire history of the Church. In subtle but unmistakable language he disassociated himself from the Curia’s narrow, defensive view of the council and urged the bishops instead to undertake a great renewal or updating of the Church. Unlike the prophets of doom and gloom among his counselors, he said, he preferred to take an optimistic view of the course of modern history. And he emphasized the need for the bishops to take a pastoral approach: They must not engage in sterile academic controversies but must find meaningful, positive, and fresh ways of stating the Church’s age-old doctrine—having no doubt in mind as he spoke the seventy ludicrously Scholastic and outdated proposals already prepared by the Curia as the basis for the bishops’ discussions.

But it was obvious to his listeners that to succeed in carrying out John’s wishes, they would first have to break the stranglehold the Curia already held over the council. The key to control over the council were the ten commissions (operating much like U.S. congressional committees), each of which had a more or less defined area of competence, such as theology, liturgy, missions, etc. Their task was to draft the documents that were submitted to the bishops for debate and then hammered out in the light of this debate and re-submitted for final approval by the bishops. In an unwieldy assembly of several thousand, the commissions exercised enormous discretionary power over what was finally to be included or excluded from the documents.

So the power struggle between the bishops and the Curia focused immediately on getting control of these commissions, each of which was to have sixteen elected and eight appointed members. The Curia had already handpicked lists of candidates, which they submitted to the bishops on the very first day, hoping to get their nominees elected before most of the prelates really caught on to the game. However, the very first speaker, Cardinal Lienart, upset their applecart when he asked how the bishops could be expected to vote intelligently for total strangers, and he moved for more time so the bishops could draw up their own lists. His motion was adopted, and the bishops adjourned.

“Bishops in Revolt!” the headlines screamed. The result, in fact, was a startling defeat for the Curial party; the men elected were, in general, independents who reflected rather well the various tendencies among the world episcopate.

They soon found that sixty-nine of the seventy draft documents already drawn up were so outdated and textbookish as to be useless even as starting points for debate and had to be completely rewritten. Fortunately, however, for the morale of the assembly there was one schema (as these documents were called) that could be immediately debated—the one on the liturgy; it was also a forward-looking and balanced document and also an ideal starting point, since as events were to show, it was the reform of the liturgy that dramatized for the average Catholic the meaning of the council.

The subsequent debate on the liturgy revealed a growing progressive mood among the bishops, who showed themselves humble enough to call in the best theologians available to bring them up to date on the latest developments. Their whole performance confirmed Pope John’s genial intuition that powerful if latent forces for change were running strong in the Church.

Voices of impressive authority spoke on both sides of the issues during the debate by the bishops. But it was soon obvious that those favoring sweeping changes were in the ascendancy. Archbishop Hallinan of Atlanta, Georgia, one of the champions of reform, noted how amusing it was at times to hear bishops speaking in elegant Ciceronian Latin while arguing for the use of the vernacular languages.

The division into liberals and conservatives or progressives and traditionalists appeared, which was soon to manifest itself time and again during the next four years: Cardinals Doepfner of Munich, Alfrink of Utrecht, Koenig of Vienna, Suenens of Belgium, Doi of Tokyo, Leger of Montreal, Ritter of St. Louis, Meyer of Chicago, and Maximos IV Saigh of Antioch, with the African bishops in a solid bloc, threw their weight regularly on the side of change, against a conservative minority. Led by Curialists, Ottaviani, Staffa, Bacci, the U.S. apostolic delegate, Vagnozzi, Irish Dominican Cardinal Browne, and U.S. Cardinals Spellman and McIntyre, the conservatives tried in vain to stem the tide. “Are these fathers planning a revolution?” Ottaviani exclaimed.

But the critical test of strength between the two mentalities came on Wednesday, November 14, 1962, when Ottaviani introduced the second draft document, On the Sources of Revelation. The first speaker, Lienart, criticized it harshly as an unsuitable statement of the Catholic position on this key issue; others noted its monolithic preference for one school of theology; its cold, Scholastic formulas; and its condemnatory and negative tone. Prestigious scholar cardinals like Alfrink and Bea echoed the same sentiments, and finally Bishop De Smedt of Bruges voiced an eloquent plea for a completely new document drafted in the spirit of dialogue with other Christians.

The fate of the council and the future of the Church really hung in the balance as the votes were gathered, for unlike the one on the liturgy, this document dealt with absolutely fundamental principles of theology and doctrine; its viewpoint was the one that had governed the Church’s thinking since Luther, the one the bishops themselves had assimilated in their seminary training and had used all their lives as their spiritual compass. To reject it would take a real act of intellectual courage on their part, for it would mean nothing less than a rejection on the intellectual level of the whole state of siege mentality characteristic of modern Catholicism.

As it turned out, the vote to reject it failed by a tiny percentage to secure the necessary two-thirds majority. At this point, the Pope intervened to break the deadlock rather than have the bishops discuss a document which nearly two thirds of them already rejected in toto. He ordered it sent back to a special commission to be completely rewritten. This was a most decisive step, and if any one conciliar act signalized the end of the Tridentine era, it was surely this.

Nevertheless, the bishops were still floundering around, and a deep sense of frustration could be felt in the baroque aula of St. Peter’s. After nearly two months of deliberations and interminable speeches, they still had no definite sense of direction. It was at this juncture that Cardinal Suenens, primate of Belgium, proposed a blueprint: Focus all debate around the idea of the Church, he urged, so that as Vatican I was remembered as the Council on the Pope, Vatican II might be remembered as the Council on the Church. Study the Church, he suggested, first in its inner mystery and constitution and then in its relation to the world. This would mean engaging in a triple dialogue: with the faithful themselves, with the separated brethren, and with the world outside. An immense outburst of applause (in violation of council rules) showed that he had hit a bull’s-eye, as did the subsequent endorsement of the idea by such cardinals as Montini and Lercaro.

Having found their way at last, the fathers were happy to take their first recess, on December 8, 1962. Before they reconvened, Pope John was taken from the world he had so captivated, and the council faced a new crisis: Would the new Pope carry through John’s bold adventure?

It was with a sigh of relief that the progressives learned of the election of John Baptist Montini as his successor, a progressive obviously committed to the Johannine revolution. Pope Paul VI was sixty-five years of age, a northern Italian of diminutive stature and solid middle-class family. His father was a journalist and member of the Italian parliament during the pre-Fascist era and very much involved in the defense of the Church against anticlericals and socialists. The bookish young Montini, whose frail health kept him from residing in the seminary during his priestly studies, was ordained in Brescia and then sent for further study to Rome, where he was invited by Monsignor Pizzardo in 1922 to join the Vatican diplomatic staff. After a brief spell in Warsaw he returned to the Eternal City, where for the next thirty years (1924–54) he served in the Secretariat of State while also acting as chaplain for a time to the Federation of Italian Catholic University Students—work that brought him into a few rowdy encounters with Mussolini’s thugs. He also worked in close association with the then Cardinal Pacelli, (later Pius XII), and traveled widely, even to the New World, and made many contacts in many countries. In 1954 Vatican politics led to his ouster and exile to Milan, where as archbishop he plunged into a ceaseless round of pastoral activity—saying Mass in foundries and industrial plants, attending sport and festival activities, and showing a constant concern with the problems of the poor and the alienated workers. Pope John made him his first cardinal and dropped broad hints of his desire to have him as a successor.

The new Pope opened the second session of the council (September 29 to December 4, 1963) with a magnificent address that reiterated the goals enunciated by Suenens: renewal of the Church, unity of all Christians, and dialogue with the world.

The debates in the second session ranged over such topics as ecumenism, religious liberty, modern communications, and anti-Semitism. The first document to command their attention was On the Church, a lengthy treatise which, as finally approved (Lumen Gentium), is one of the most important statements of the council. Its most controversial chapter proved to be the second one, which dealt with the doctrine of collegiality or the right of the bishops to participate as a body in the full and supreme authority of the Pope over the Church. Although this idea was deeply rooted in tradition, it appeared heretical to the conservatives accustomed to Pacelli’s type of absolute monarchy.

The sharp division of opinion over the issue precipitated another crisis. The theological commission, headed by Ottaviani and charged with making the necessary revision in the document, moved at a snail’s pace, and, in fact, a significant number of its members were opposed to the idea of collegiality as a dangerous infringement on the Pope’s authority; they filibustered while seeking a way of watering down the statement.

But the four moderators led by Suenens circumvented them by submitting five questions containing the substance of the chapter directly to the assembly. The answers, they figured, would clearly indicate the mind of the bishops on collegiality and hence would stop the filibuster and force the commission to incorporate the results of the vote in their document. But the other directing agencies of the council—the presidents, the coordinating commission, and the secretariat—questioned the moderators’ right to submit such a vote to the assembly. A conflict raged behind the scenes; finally, a compromise was reached: The moderators would be allowed to submit their orientation votes this one time, but not again. The accord was reached, no doubt, with the help of Paul VI, who showed his attitude at a special Mass when he warmly embraced the cardinal of Malines, who had just delivered a sermon urging the bishops not to lose courage but to continue to respond to the Pope’s invitation to travel the road of dialogue and openness.

The vote by the bishops showed a definite preponderance in favor of collegiality, resolving the issue and decisively confirming the progressive tendency of the council.

Another moment of drama occurred a little later, when Cardinal Frings of Cologne sharply criticized Ottaviani’s Holy Office for its methods, such as condemning writers without even a hearing; Frings called them a scandal to the modern world. The object of the attack—the old, nearly blind son of a baker from the tough Roman Trastevere slums—rose to his feet and vehemently rejected the accusation as due to ignorance.

The third session (September 14 to November 21, 1964) opened with a liturgical demonstration of collegiality as the Pope and twenty-four bishops concelebrated a Mass. One of the most important debates of this session had to do with the previously mentioned schema, On the Sources of Revelation, now called simply On Divine Revelation; it was now completely rewritten and reflected progressive theological tendencies in its acceptance of the results of modern biblical and historical research.

Debate was also begun on Schema 13, The Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes), undoubtedly the most ambitious project of the Council both in its length and scope as well as in its objective, which was to begin a realistic dialogue with the modern world. During the debate on this schema, Cardinals Leger, Suenens, and Alfrink created a great stir when they called for reappraisal of the official Catholic teaching on marital morality, especially in regard to the problem of artificial birth control.

Another delicate topic that required treatment in any dialogue with the modern world was the question of religious liberty. If the Church was to speak with any effectiveness to the world, it certainly had to update its stand on this matter. The classical Catholic position, as enunciated in the Syllabus of Errors, claimed preferential treatment of the Catholic Church by the state while according only tolerance to other religions. This was a terribly burdensome anachronism for progressives and, led by the Americans, they asked for a statement proclaiming the Church’s total commitment to complete religious liberty. A draft statement was finally drawn up by Cardinal Bea’s secretariat for Christian unity.

It was generally known that a powerful minority led by Ottaviani still held to the old principle that error has no rights and were trying to bottle up the document in the commissions. Many of the bishops therefore were very ill at ease and wanted the vote taken as soon as possible. So they reacted strongly when on November 19, Cardinal Tisserant suddenly announced that no vote would be taken at that session on the question of religious liberty. The words brought the bishops to their feet; they swarmed into the aisles and milled around, obviously dismayed and upset. Someone grabbed a piece of paper, and a petition was hastily drawn up on the spot, quickly signed by more than four hundred, and then presented immediately to the Pope by a delegation led by Cardinals Meyer and Ritter. Paul refused, however, to contravene Tisserant’s decision, and the matter was left hanging in suspense until the fourth session.

The bishops were also annoyed by a number of unilateral papal interventions instigated, no doubt, by the conservatives: The Pope, in order to pacify the minority, made last-minute changes in several key documents. One such change, in the constitution On the Church, emphasized papal primacy and the independence of the Pope at the expense of collegiality; another rendered the decree On Ecumenism less conciliatory toward the Protestants. Since these insertions were made right before the final voting on the documents, the bishops were practically forced to accept them or otherwise risk losing the entire documents. Distasteful as they were to the majority, they were nevertheless the price of obtaining virtual unanimity in the final balloting.

In the interim between the third and the final session Paul journeyed on a pilgrimage to the Eucharistic Congress in Bombay, where his reception by millions of Indians surpassed all expectations. Even the Communist press admitted that the exuberant crowds, the cheers, and the excitement exceeded anything in recent memory. He returned in time to open the fourth session (September 14 to December 8, 1965) and received a thunderous “Viva il Papa!” when he announced that he would personally go before the United Nations General Assembly to make an appeal for peace.

Tops on the agenda was the statement on religious liberty, which after much revision appeared satisfactory to the progressives. It affirmed the right of persons not to be coerced in any way in their religious beliefs and practices, and it acknowledged that the Church had at times sinned against this principle. American cardinals Cushing, Spellman, and Ritter gave the draft statement ringing endorsements. Cardinal Heenan quoted Newman’s famous toast to conscience first and then to the Pope. But the intransigent traditionalist leaders Ruffini, Siri, and Carli, with the majority of the Spanish bishops, worked strenuously to delay voting. But this time the Pope stepped in and insisted on a vote being taken immediately. He did not dare to appear before the United Nations without a decisive vote of the council in favor of religious liberty. The balloting indicated an overwhelming majority in favor of the document’s strong affirmation of freedom.

Paul’s visit to the UN in October was synchronized ingeniously with the discussion in the Vatican Council of the fifth and final chapter of Schema 13, “The Community of Nations and the Building Up of Peace.” The Pope’s ratification of the UN as he spoke to the assembled nations in person was one of the great moments of the Vatican Council. A TWA Boeing 707 sped him afterward back to Rome, and forty-six minutes later he alighted from a black Mercedes at the portico of St. Peter’s and again received a tremendous “Viva il Papa!” from the bishops.

They were kept extremely busy putting the final touches to a wide variety of documents that were promulgated at that session: They dealt with the pastoral office of the bishop, priestly life and ministry (which skirted clear of the vexing problem of celibacy), a condemnation of anti-Semitism, the renewal of the religious orders, seminary training, Christian education, the missions, the lay apostolate, and non-Christian religions. Two documents in particular—the constitution On Revelation and the pastoral constitution On the Church in the Modern World—generated intense debate before they were finally approved and promulgated.

The final voting session was attended by 2,399 bishops, and then the closing was celebrated with a ceremony outside in the piazza witnessed by thousands of pilgrims and sightseers and carried to the world by television.

The Second Vatican Council, the twenty-first in the history of the Church, was undoubtedly the most important religious event of the twentieth century to date. It brought some 2,500 of the top leaders of the world’s largest religious body together for four three-month sessions over four years and engaged them in debate on most of the vital religious issues facing mankind. It issued all told some sixteen documents (four constitutions, nine decrees, and three declarations), which won the virtually unanimous consensus of the participants and which when implemented would produce far-reaching changes in Catholic communities around the world. It was the first ecumenical council in history to assemble with hardly any interference from secular governments, and the first to have other Christians in attendance as official delegates of their respective Churches.

Only time would tell, of course, which of the documents issued by the Council would prove of lasting significance and which would be remembered only as a celebration of the Zeitgeist. But it seems that at least five of its major changes will have a lasting effect.

First, the changes brought about in the liturgy—principally in the Mass—were the most visible and startling to the average churchgoer. The decree on the liturgy provided for translating the Latin text into the modern languages, and urged all concerned to make the liturgy intelligible to the layman and to secure their participation in the fullest manner.

Second was the definite advance in the Church’s self-understanding as reflected especially in Lumen Gentium. Since Luther’s day at least, the Catholic doctrine of the nature of the Church—as formulated in the works of theologians like Bellarmine—put much emphasis on its institutional, juridical, and hierarchial character; a rigid separation was posited between the clergy and laity—the clergy ruled, the laity obeyed. Treatises on the Church made much ado about who had what power over whom. This kind of thinking reached its apogee at Vatican I, which conceived of the Church in a very authoritarian way.

Vatican II definitely moved away from such a legalistic view. Lumen Gentiumshifts the emphasis from the Church as a pyramidal structure to the Church as the whole people of God, and it lays stress on the fundamental equality of all as regards basic vocation, dignity, and commitment; it dwells on the common priesthood of the faithful. Office in the Church is seen as primarily one of service to the community. Authority is seen as the means of promoting the intimate fellowship of the Church, a fellowship that finds its principle of unity indeed in the collegial fellowship of Pope and bishops as successor to the apostolic college but that widens out to embrace all the members in a sweet fraternity of love and mutual service. The affirmation of the collegial relationship of Pope and bishops was, no doubt, the most important single contribution of Lumen Gentium, since it corrected the tendency to see the Pope as somehow isolated and set over the Church. The practical import of all this created a veritable revolution in the machinery of the Church as a greatly increased number of persons were drawn into the decision-making process on every level.

Third was the change in attitude and practice as regards other Christians. Rome held aloof from the ecumenical movement among Protestants until Pope John’s arrival on the scene. Then the council slowly caught on to the spirit of his new approach to Christian unity. Its document on ecumenism (Unitatis Redintegratio) put the whole matter of Protestant-Catholic relations in an entirely new perspective. The ultimate goal of ecumenism was no longer viewed as the return of individual Protestants to the Catholic Church; the objective now was rather the reunion of all the separated brethren, whose status as true ecclesial communities was recognized. To hasten the day of reunion, Catholics were encouraged to enter into dialogue with other Christians, to engage in common prayer with them, and as far as possible to work in concert with them on social problems. Doctrinal difficulties were not minimized, nor did the council renounce the Catholic Church’s claim to unique ecclesial status as containing the fullness of the means of salvation, but attention was drawn to the vital elements of the Christian tradition that were already held in common with most other Christians. Finally, the Catholic Church publicly confessed its own share of guilt in causing and perpetuating Christian disunity and committed itself solemnly to a continual self-reformation—which would involve correcting its own deficiencies, even extending to its past formulations of doctrine.

Fourth, the Council showed a much greater regard for the historical dimension in the Church’s faith and life. In place of the nonhistorical Scholastic theology, with its emphasis on immutable ideas and essences, which since the days of Thomas Aquinas characterized Catholic thought, Vatican II manifested an openness to the totality of Christian and human history and fully recognized the historical conditioning that has affected every aspect of its tradition; even its sacred books, which previously were regarded as the work of a few human authors whom God had inspired to reveal his message, were now viewed as intimately involved in human history. “Liturgical forms and customs, dogmatic formulations thought to have arisen with the apostles now appeared as products of complicated processes of growth within the womb of history.”123 The use of the historical-critical methods of research was countenanced by the fathers, who finally faced squarely this portentous issue first raised by the Modernists.

Finally was the council’s call for dialogue with the modern secular world. This is especially the theme of its pastoral constitution, On the Church in the Modern World—a statement that marks a new departure in ecclesiastical literature in many respects, but especially in its language—so free of all archaic terminology—and in the utter realism with which it faces the Church’s situation; it seems to embody more clearly than any other documents of the council the big heart of Pope John himself, pervaded as the document is with the spirit of love and concern for the whole human family. For the first time in modern history, the Church accepts the progressive cultural and social movements of modern history, which it previously regarded with much skepticism if not outright condemnation. It notes without regret the passing of old forms of thought and feeling and social relations, and while not indulging in naïve optimism, it sees the possibilities for human liberation that all of this entails. Abandoning its Constantinian and Tridentine triumphalistic manner, it places itself humbly at the service of humanity and points out how both Church and world can find common ground in their mutual recognition of the dignity of the human person and the nobility of his vocation to build the human community.