In 1996, the City of Scarborough celebrated its two-hundredth anniversary. Whether or not what happened in that period is worth celebrating depends upon your perspective. From forest to farm and to endless sprawl, the face of the old township has changed dramatically. Roads of four or six lanes trace the routes of the first concession roads, such as Eglinton, Lawrence, and Ellesmere, or sideroads such as Kennedy, McCowan, or Markham Roads, while Kingston Road and Danforth Road reflect early pioneer trails. At key points where these farm roads intersected, there grew vital villages. Those fields and forests have long been replaced with sprawling subdivisions, strip malls, bigbox outlets, and gridlocked traffic, even though transit has improved with GO service and TTC routes.

In 1793, when the township was surveyed, it was a land of forests, ravines, and, of course, its famous bluffs. These yellow cliffs of clay and sand inspired Elizabeth Simcoe, the wife of Ontario’s first governor, John Graves Simcoe, to name the area after the chalk cliffs of her native Scarborough, England. Before the Simcoes had departed, in 1796 Asa Danforth hacked through the undergrowth to lay out his winding Danforth Road to the Bay of Quinte, a path so tortuous and poorly located that it was quickly replaced with a straighter Kingston Road.

Still, settlers remained few. David and Mary Thomson were the first, struggling in 1799 to assemble their crude log cabin on the banks of the Rouge River beside a now forgotten trail to Markham. Over the next twenty years a small settlement grew up around their cabin and became known as St. Andrews.

Another early arrival was William Cornell, who in 1804 built the area’s first mill near the mouth of the Rouge River. Still, by 1820 the settler population of the whole township remained less than five hundred.

Transportation was the problem. Roads then were quagmires at best, on which stage drivers felt lucky to make a dozen kilometres a day. Taverns abounded on the Kingston and Markham Roads as rest and respite stops for weary teams, and wearier passengers. As stage drivers were usually rewarded by tavern owners for halting at their establishments, such rest stops were often even longer and more frequent than necessary.

Then, in the 1820s and again in the 1840s, what had been a trickle of European immigration turned into a flood. Wealthy landowners in Ireland and Scotland were driving out peasant farmers through starvation and land consolidation, and many made their way to the growing town of York. The fertile soils of Scarborough were close at hand and the population tripled in just thirty years.

Scarborough’s early road pattern was typical of an Ontario farming township. In addition to the pioneer Danforth and Kingston Roads, and the now-vanished early route of Markham Road, Scarborough’s roads were laid out in a grid. Along the concession roads (like St. Clair, Eglinton, Lawrence, and Ellesmere), which ran generally east-west about two kilometres apart, the farm lots were surveyed. Sideroads (such as today’s Kennedy, Brimley, Bellamy, and Warden) were laid out at right angles to the concession roads and about a kilometre apart.

Before the automobile, travel was tediously slow — as it sometimes still is. Roads were often scarcely passable. Farmers needed everything close at hand; the stores where they could shop and, more importantly, pick up their mail; blacksmith shops and harness shops; churches for worship; and taverns for recreation. And so, at most of the important intersections, crossroads hamlets appeared.

Until the Second World War, the township was one of Ontario’s most prosperous farming areas. Fields of hay and grain waved in the breeze, while cattle grazed lazily in lush green pastures. Farmhouses of brick or stone lined the dirt concession roads, behind them the sturdy barns. A few newfangled automobiles clattered along, raising clouds of dust and startling the teams that still plodded along, dragging their creaking hay wagons. Distant whistles and columns of smoke heralded another train with its line of red boxcars or green passenger coaches. But with the end of the war and the advent of the 1950s, that idyll would vanish forever.

Although it was due to open at the same time as the Queen Elizabeth Way, in 1939, the bypass across the north end of the township that eventually became the 401 was delayed by the war and not completed until 1955. Even without it, however, the effects of the auto age were already being felt.

Proximity to the burgeoning city of Toronto, which had until then been a boon to the farming community, would now cause its demise. With the car craze came the suburbs. Unplanned at first, many just appeared wherever the speculators wanted them, regardless of whether the municipal necessities of sewers and water existed. Mills, farmhouses, and hotels came tumbling down to make way for the endless rows of backsplits and sprawling industries. Many of the old crossroads hamlets have long been replaced by turning lanes, fast-food outlets, and gas station/convenience stores, and the mill sites cleared away for parkland or housing. The once-tranquil farm lanes were widened and paved to welcome in the auto age.

To anyone braving these six-lane car canyons, where strip malls stretch to the horizon, the place seems bereft of any history at all. Yet, thanks to groups like the Scarborough Museum and the Historical Society, there remain small islands of history — an ancient church surrounded by tall trees and aging tombstones, a few quiet one-time village streets, a handsome old stone house — surviving in this sea of suburbia.

Opened by Asa Danforth in 1799, his Danforth Road was poorly built and fell into disuse. By 1804, Kingston Road had mostly replaced it. The trail, however, carried on as a local farm road, providing access into northern Scarborough. Various local streets today follow much of that alignment, including Clonmore Drive, Danforth Road, Painted Post Drive, Military Trail and Colonel Danforth Trail.

At the intersection of Danforth Road and Birchmount Road (as it is known today), a small post office was opened on the property of one Brown on the southeast corner of the intersection. A short distance east a school stood on the south side of Danforth, while a trio of farmhouses clustered about the crossroads. Today, Danforth is four lanes wide and commercial development has taken over the intersection.

At today’s St. Clair and Danforth Road, a busy crossroads settlement developed. Known as Bell’s Corners, this was the junction of three roads — today’s St. Clair, Kennedy, and Danforth. The location included The Farmer’s Inn, Bell’s general store, and Emp’s blacksmith shop.

In 1856 the Grand Trunk built its Montreal line a kilometre to the east of the intersection, and in 1873 the Nipissing Railway chose the area for its junction point with the GT. The railway community where they came together boomed and was named Scarborough Junction. A townsite was created and new stores and houses appeared (see chapter 9, on railway towns).

Today’s multi-lane Danforth Road still follows much of its earlier alignment. Indeed, three early farm homes can still be seen on the north side of Danforth Road between St. Clair and Brimley; 770, 786, and 972 Danforth. On the northwest and northeast corners of Kennedy and St. Clair, a cemetery and condo development, respectively, have replaced the store and shops, as has a gas station at the northeast corner of St. Clair and Danforth, while small commercial malls have taken over both south corners of Kennedy and St. Clair. One of the area’s last original structures is 661 Danforth Road, a two-storey house adjacent to a car dealership.

Bendale represents Scarborough’s most historic site, the place where European settlement took root. Here, where the early trail to Markham wound its way northeastward, David Thomson and his brother Andrew erected their crude shanties. The year was 1797, when Yonge Street was only a year old, and Asa Danforth had only begun to clear the forests for his road east. It was a particularly difficult time to be trying to locate and clear land in what was then a daunting forest.

The community at first went by the name of Benlamond and was centred on Danforth Road and Lawrence. However, because that name was also used for a community near Norway on the Kingston Road, the post office name chosen was Bendale.

The community was more a scattered rural community than a concentrated village. A short distance from the Thomsons, John Wheler constructed a sawmill on the west side of Brimley and south of Ellesmere, and shortly thereafter a gristmill. The gristmill burned down in 1863.

In the 1840s, the Thomson sons built new houses, James building the house he called “Springfield” east of the family homestead, and William adding “Bonese” to the west. Between the two, the community added a handsome brick church, beside which a library building was added in the 1890s. A quiet farm road twisted its way past the Thomsons and the church, connecting Brimley and McCowan.

During this period, the Thomson family controlled most of the farmland between Kennedy and Brimley, and between Lawrence and Ellesmere. Many years later the Canadian Northern Railway line crossed the Thomson land, but apparently no station was built on it.

The suburban tide rolled through this area during the 1960s, but, rather than obliterating Bendale, left much of it intact. This preservation victory is because of the foresight of the hard-working members of the Scarborough Historical Society, who managed to save the church and both Thomson houses. All stand today on St. Andrews Road, and are celebrated with historic designations. The church, one of Scarborough’s oldest, was built in 1848, replacing the original built in 1818. A short distance west, a clapboard house was added in 1883 for the sexton, the church groundskeeper. The small building still standing in front of the church was added in 1896 as the first Bendale library. A short section of the road itself has retained many of its early characteristics, narrow and winding, as it passes through the woodland that yet surrounds the old church: a miniature landscape from the past.

St. Andrew’s is one of Scarborough’s oldest churches.

“Springfield,” at 146 St. Andrews Road, has been designated as a heritage structure, and holds associations with such Canadian luminaries as Lord Thomson of Fleet and Farley Mowat. Farther west, at number 1, where St. Andrews meets Brimley, the elegant, stone “Bonese” is also designated “historic.”

Here, too, is the Scarborough Historic Museum. The grounds include four buildings moved to the site between 1962 and 1974: the Cornell House, a clapboard vernacular-style farmhouse; the McCowan Log House, restored to its 1850s appearance; the Hough Carriage Works, displaying a collection of artisan’s tools; and a one-time farm outbuilding that now contains the Kennedy Gallery. Even a portion of the long-abandoned Canadian Northern Railway right-of-way has become a footpath through the park. Entrance to the park is from Brimley Road just north of Lawrence Avenue. Not too far away, on Bellamy north of Lawrence, sits the Taber Hill Ossuary, an Indigenous people’s burial mound.

Woburn’s place in the history of Scarborough goes beyond the few buildings that constituted the long-vanished hamlet. Here, at the intersection of the old Danforth Road and the Markham Road, an earlier pioneer, Thomas Dowswell, built a tavern and called it the Central Inn.

In 1850, Scarborough, like many other townships in Ontario, was granted municipal status. Finally, decisions that affected the township could be made by the township’s own residents. All they needed was a place to meet. Because Dowswell’s tavern stood in the middle of the township, the first councillors began to meet there. The original name of Elderslie was rejected as the name for the new post office because an Elderslie already existed in Grey County. Instead, it was named after Woburn, Dowswell’s hometown in England. Soon afterward a township hall was erected and saw many heated council sessions in the chambers. In 1922 the office was relocated to Birch Cliff near today’s Kingston Road and Birchmount, an area then just beginning to feel the pincers of Toronto’s urban growth.

Back up at Woburn, the old hall burned down in 1927, while Dowswell’s hotel lasted into the 1960s, when it was demolished to make way for Scarborough’s inevitable suburban growth. The old Danforth Road in this area now goes by Painted Post Road and is a residential street. A small parkette at the northeast corner of Markham and Painted Post offers a stone memorial to Dowswell’s historic tavern with a plaque marking the spot where Scarborough “began.” It was erected by the Scarborough Historical Society in 1975.

One year after St. Andrew’s Church was built, another church was being constructed on “Dawes Road,” an early pioneer wagon trail, just south of Lawrence. Modelled after the first pastor’s home church in England, St. Jude’s Anglican Church was described by an early writer as a “perfect gem.” Built by local farmers, its style is noticeably different from the usual symmetrical church structures then popping up all across Ontario.

Wexford began, as did so many crossroads villages, with a tavern. It was around Richard Sylvester’s “Rising Sun” tavern that a hamlet with a general store and blacksmith shop grew. On the south side of Lawrence, the Roman Catholic community added a church, and, in 1876, a Methodist church was built some distance to the east, near the corner with today’s Birchmount Road. It was known as Twaddle’s Chapel, to honour the farmer who donated the land. Despite the arrival of the Ontario and Quebec Railway in the 1880s, which added a small flag station, Wexford remained small, with many of its early buildings lining Lawrence between Dawes Road and Pharmacy. As urban growth spilled northward, Dawes Road was widened and renamed Victoria Park Avenue, bringing with it plazas, apartments, and houses, and sweeping Wexford away.

Out of place amid modern apartments, St. Jude’s could be a country church in England.

The little railway station had already gone, burned down in 1933, and the remaining buildings that clustered around the crossroads were obliterated. The Catholics replaced their old building with the more modern Precious Blood school (on Pharmacy Avenue at Inniswood Drive) and church (1737 Lawrence Avenue East), which stand today.

The most surprising vestige of the old farming community is the “perfect gem,” St. Jude’s. Looking every bit the English country church, this white Gothic building seems startlingly out of place, almost hidden among neighbouring apartment blocks. Drivers hustling along the busy lanes of Victoria Park Avenue south of Lawrence may scarcely notice the pretty wooden church, set back across from Sloane Avenue, in a grove of trees.

Now swamped by modern subdivisions, O’Sullivan’s Corners is one of Scarborough’s many vanished farm hamlets.

Close by Wexford stood the community of O’Sullivan’s Corners, little more than a hotel with a post office in it. It was at the intersection of what is today Old Sheppard Avenue, north of Sheppard Avenue’s current intersection with Victoria Park. The landscape today is one of post-war suburban homes and a large shopping mall.

The hamlet was started by Patrick O’Sullivan in 1860, and in 1892 gained the post office. For many decades after the arrival of the car, the hotel remained a favourite eatery for the area’s Sunday drivers. The hotel was demolished in 1954, but Alex Muirhead’s 1853 brick farmhouse, engulfed now by modern suburban homes, still stands at 179 Old Sheppard Avenue.

Finch Avenue is one of Scarborough’s busiest suburban routes. Six lanes of traffic hurry residents to their stores, schools, and workplaces, often via the nearby Highway 404, or on arterial roads like Leslie Street or Don Mills Road. Residential subdivisions sprawl across the former farm fields along Finch, while malls and supermarkets dominate the main intersections.

Situated around the busy intersection of Finch and Dawes Road (now Victoria Park Avenue), L’Amoreaux was named after a family of settlers who arrived in 1816. Early business surveys in 19th-century Scarborough could not agree on the spelling of the place and it appears variously as L’Amoreaux, L’Amoroux, and L’Amorioux.

The hamlet grew to include a school, blacksmith shops, a wagon factory, a sash factory, and a couple of nearby churches. On the southwest corner stood James Lang’s store — containing the all-important post office — with the blacksmith and wagon-maker sitting to the west of it.

This was one of those odd places where two roads, surveyed from opposite directions, did not meet. Victoria Park marks the boundary between the old townships of Scarborough and North York, and the townships had different road survey patterns. As a result, North York’s Finch Avenue met Victoria Park about half a kilometre north of where Scarborough’s Finch Avenue met it, creating a dogleg for through traffic on Finch. To make for a smoother traffic flow, the former has been rerouted to meet the latter at Victoria Park.

The old portion of Finch that the new section bypassed has become Pawnee Avenue and is a residential street in a subdivision, with no evidence that it was ever a tranquil farm lane.

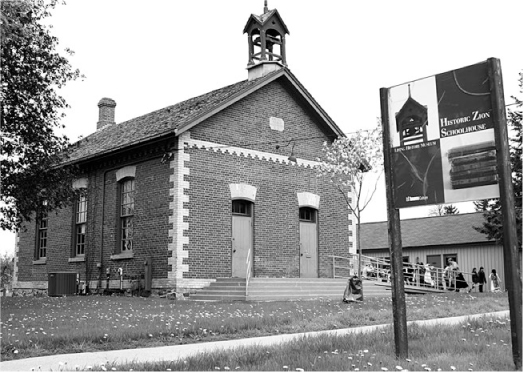

While most of the old crossroads buildings have vanished, a couple of L’Amoreaux’s more important structures still stand, strangely out of place in the sea of suburbia. Relative to the crossroads hamlet, they were both country sites, located amid the rolling farm fields along Finch east of Leslie Street. They include the North York Zion Schoolhouse, now preserved by the City of Toronto, standing as it has since 1869 on the south side of Finch east of Leslie Street. It has been restored to a 1910 appearance and functions today as a schoolhouse museum for school trips and as an event venue.

The historic Zion school is now a place where students learn how children were schooled in the past.

A short distance farther east, on the north side at 1650 Finch and built just four years later, is the brick Zion Methodist Church. In a neighbourhood of towering apartment buildings, it has become the Zion Church Cultural Centre. The graveyard around it contains the stones that commemorate many of those early settlers — who would be astonished at how the area has changed.

The old community of Hillside contains one of Ontario’s premier tourist attractions, the Metro Toronto Zoo. Yet few Zoo patrons have likely even heard of the little hamlet. Here too is the newly inaugurated Rouge National Urban Park, with its wooded hillsides, its rushing river and popular trails.

European settlement (there had already been a Seneca village nearby) began around 1840 with the sawmill operations of William Milne, located at Old Finch Avenue, and Sewell’s Road. His mill outlasted the other nearby mill operations along the Rouge River before shutting down in 1929 with the timber supply depleted. Nearby, his son, William A. Milne, in 1877 built a handsome homestead he named Hillside. The community was scattered along Finch Avenue between the Rouge River and Meadowvale Road and included a school, a church, and a number of mill workers’ homes.

While newer homes have invaded the wooded hillsides of this riverine area, Hillside has yet to be completely engulfed by the urban tide. Old Finch and Sewell’s Road yet wind through the forested valley of the Rouge, much as they have for decades, and cross the river on Ontario’s only surviving suspension bridge, a structure that was designed by Frank Barber and completed in 1912 for a mere $8,000. A 1904 descendant of the first school (ca. 1853) now serves as a daycare.

But the prize of the area remains the historic board-and-batten church, on the south side of Old Finch at the intersection of Reesor, a structure that dates from 1877 and is still surrounded by trees and open space. Some distance west, the historic Carpenter Gothic Hillside House still stands, now saved as part of the Rouge National Urban Park. Belonging to Hilltop Farms, it stands back from the road at the northwest corner of Sewell’s Road and Old Finch Avenue.

The Hillside Church’s unlikely neighbour is the Toronto Zoo.

It’s hard for anyone carried along by the ceaseless flow of traffic on Scarborough’s Eglinton Avenue, as it nears Birchmount Road, to believe that this area could ever have been a tranquil dirt trail through farm country. Yet this very intersection, mere decades ago, heard only the sound of horses’ hooves hauling hay wagons past fields of blowing grain.

In 1804 John Hough settled in the area and a decade later was operating a sawmill and a wagon shop and blacksmith shop, all on the southwest corner. A school and church were soon added nearby, and the crossroads became a busy farm hamlet. However, after the Second World War, Scarborough’s township council began promoting the area as the “Golden Mile of Industry,” and the farmland and hamlet vanished beneath sprawling factories. The area keeps changing. Malls have replaced the factories, and a rapid transit line, to be completed along Eglinton in 2021, will change the face of Scarborough once more. Apartments and houses took over Birchmount and the hamlet has vanished. All that’s left is the cemetery, on the east side of Kennedy south of Eglinton.

A lost village of sorts, too, is the Second World War munitions complex that was created south of Eglinton and east of Warden. Home to the legendary female workforce known as the “Bomb Girls,” some of the wartime buildings and a few of the tunnels that linked them still survive along roads like Civic Road, Manville Road, and Sherry Road.

The name will be familiar to many, but for the wrong reasons. Today’s generation knows it as yet another of those traffic arteries responsible for the usual suburban noise and pollution, today dominated by malls and cut-rate retail outlets. Yet the name derives from a busy farm village that once centred on the intersection of Ellesmere and Kennedy.

In 1820, Archie Glendinning braved the then wilds of distant Scarborough to build a general store for the nascent farm community. The place grew slowly, and it wasn’t until 1853 that a post office was finally permitted in Glendinning’s store, which he operated from his fine stone farmhouse. By then the place could boast two blacksmiths and two general stores, along with carpenters, jewellers, and shoemakers, and a number of houses on the northeast corner. The Forfar (or Forfair) family had three members involved in the hamlet’s businesses, including a butcher shop, one of the blacksmith shops, and a wagon factory. The directories of the day estimate the community’s population at around one hundred. In 1884, the CPR built its line through Agincourt to the north, and Ellesmere became a backwater.

The farm hamlet of Ellesmere is unrecognizable today. It has been obliterated by wide suburban streets.

Nonetheless, many of these buildings still stood into the 1960s and ’70s, when Kennedy Road began to develop into a commercial strip. Sadly, the historic Glendinning store, built in 1830, was short-sightedly demolished as recently as 1980 to make way for a new, cookie-cutter-style bank building. All other evidence of this historic community has utterly vanished, replaced by Scarborough’s urban sprawl.

Today, this one-time pioneer crossroads hamlet has become the centre of the Toronto area’s newest residential community, which makes it even harder to visualize it as a place where teams of horses plodded along, and wheat fields waved in the warm summer breezes.

Milliken was at the intersection of Kennedy Road and Steeles Avenue. The area’s earliest settler was a Loyalist named Norman Milliken, who arrived in 1807 and established a sawmill and hotel. Soon after came Ferguson’s general store, and Henry Boatten took over the hotel. Still later, the Toronto and Nipissing Railway built a small, shelter-sized flag-stop station to serve the community.

This was another of those disjointed intersections. Scarborough’s Kennedy Road met Steeles about half a kilometre west of where Markham Township’s version joined it. Most of the hamlet centred on the easterly of the two corners and survived more or less intact well into the 1960s, when the area was still popular for its market gardens and pick-your-own vegetable farms. It was one of the last areas in Scarborough to become engulfed in the tide of suburbia: monster homes and mega malls have replaced the farms.

Only a few older village houses survive on the east side of Old Kennedy north of Steeles, amid a clutter of industrial buildings and storage yards. The GO commuter station south of Steeles stands on the grounds of the old station flag stop and is today the only visible reminder that a “Milliken” even existed.

Milliken’s most prominent landmark today lies at the intersection of Steeles Avenue with “new” Kennedy Road: the massive Pacific Mall complex, dominated by Chinese shops and restaurants.

Malvern, at Markham Road and today’s Sheppard, was one of those places that had dreams of becoming a thriving village in its own right. It got off to a promising start, but the railways bypassed it and it became a backwater, almost an early “ghost town.” While the early street patterns remain visible amid the new housing, the intersection today is dominated by six lanes of traffic, local malls, and gas stations.

Markham Road, although less well travelled than Kingston Road, nevertheless was a busy pioneer artery, linking Kingston Road with the thriving settlement of Markham that the Berczy settlers had founded. Here, at the intersection of Markham Road and what was then the Lansing Road (now Sheppard Avenue) that led to Yonge Street, John and Robert Malcolm opened the Speed the Plough inn. The place’s early name was Brown’s Corners, after the area’s first postmaster.

The large station that the Canadian Northern Railway added in Malvern did little to help the village grow.

Not content to leave the place as just another crossroads hamlet, in 1857 David Reesor laid out, on the northeast corner, a town plot with a half-dozen village streets and numerous house lots. But he needed to give it an appealing name if he was to attract buyers. Having heard from locals of a nearby spring whose waters had curative powers, Reesor gave it the name of Malvern, after a place in England whose waters were also reputedly “magic.”

The place started promisingly enough, adding a church, two stores, two blacksmiths, a wagon shop, Badgerow’s woollen factory, and a couple of hotels. But its early promise faltered when the Grand Trunk Railway built its line well to the south. With new businesses flocking to rail-side, Malvern’s growth slowed. Many of the housing lots remained vacant, and the community resigned itself to being just another crossroads hamlet.

Malvern did become widely renowned for its popular Mammoth Hall. Built in 1879 (replacing a smaller version destroyed by fire), it included a curling rink, a dance hall, and a hall for the area’s many political meetings. Although Mammoth Hall was designated as a heritage building, an arsonist ended its life in 1988, to local controversy, just as the area was opening up to new development. (Possibly a case of “heritage lightning”? That is the term those concerned with heritage preservation sometimes use to explain the odd coincidence that arises when a structure is designated “historic,” and then suddenly burns down.)

Hopes were raised in 1911, too, when the railway-building duo of William Mackenzie and Donald Mann announced that Malvern would have a station on their new Canadian Northern Railway line to Ottawa, and indeed the station was a handsome, wooden, two-storey building with operator’s living quarters on the second floor. But Ontario did not need three main lines running east from Toronto, and the Canadian Northern Railway failed. It was absorbed by the Canadian National a few years later and abandoned. Indeed, by the 1960s, most of Malvern’s early functions had ended, and the fringe of suburban growth crept closer.

Only one of the village homes has managed to survive, that at 16 Ormerod, one of Reesor’s village streets. It leads east from Markham Road, just north of Sheppard. The remaining village streets are now home to rows of new housing. As the farm fields once did, suburbia now sprawls in all directions.

Amid a sprawling industrial area, the Armadale church, one of Toronto’s oldest Free Methodist churches, is a designated heritage structure.

Short-sighted modern-day developers have typically chosen to ignore the area’s heritage, and the rest of the village site lies beneath condos and shopping plazas. For David Reesor, that would have been good news, but it came too late.

If anything survives of Scarborough’s early crossroads hamlets, it is usually the church. This holds true with the vanished hamlet of Armadale. Here, near the intersection of today’s Markham Road and Steeles Avenue, now a vast expanse of industrial sprawl, the hamlet contained the usual tavern, blacksmith, and general store, as well as a temperance hall and a brickyard. The post office opened in 1869 with the unusual name of Magdalla. However, the name was soon changed to Armadale and stayed that way.

The hamlet’s first store sat on the southwest corner, another just south of that, with a blacksmith shop behind it. Here too stood the temperance hotel. All are gone. Still standing, however, is the Armadale Free Methodist Church, Canada’s oldest functioning Free Methodist Church. Built in 1880, it is now designated under the Ontario Heritage Act. It stands south of Steeles, incongruously surrounded by modern factories and industrial supply houses, less than a kilometre west of Markham Road on Passmore. The burial ground stretches to its east, while a board-and-batten house of similar period stands to its west.

East of the Armadale church, the historic Weir house, one of Scarborough’s wonderful early stone farm homes, was rescued from demolition by the Runnymede Development Corporation, which moved it away from the tracks and closer to the road. It stands at 1051 Tapscott Road, south of McNicoll Avenue. Built in 1861 by Scottish immigrant James Weir, its stone lintels were imported from quarries in Kingston, while local fieldstone was used for the walls, which are sixty centimetres thick. This solid home included three fireplaces and three bedrooms.

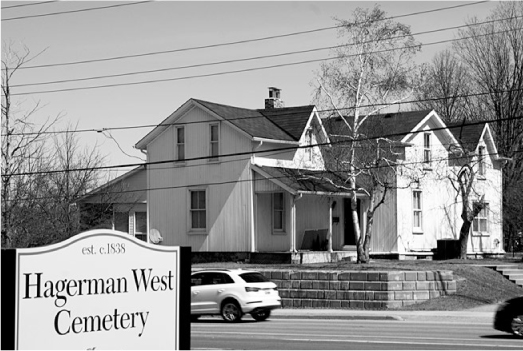

Named after Nicholas Hagerman, one of the early German settlers who accompanied William Berczy into the remote forested lands, Hagerman’s Corners is at the now-busy corner of Kennedy Road and 14th Avenue. Suburban housing spreads to the east, and large event venues mingle with industries and restaurants to the west. Today’s landscape is a far cry from the original, when it contained only a hotel, a store, a shoemaker, and two cabinetmakers, and a population estimated at one hundred. A church was built beside the Hagerman’s private burial grounds.

One of the few buildings to survive the obliteration of Scarborough’s Hagerman’s Corners, this historic house is now part of a Montessori school.

William McPherson opened the hamlet’s first general store in the 1830s, and James Fairless added another in the 1850s. That one later became Galloway’s and lasted until recent times. The hotel known first as Webber’s was taken over by “Tom” Hemmingway and renamed the Beehive, with a poem on its sign that read:

“Within this hive we’re much alive

Good liquor makes us funny

So, if you’re dry, come in and try

The flavour of our honey.”

Much of this little community still survived into the 1970s, when the suburban fringe appeared on the horizon and then swept into the community. About a kilometre to the west of the intersection, the former school lives on at 4121 14th Avenue, converted into a fine-dining restaurant. Only one 1850s-era home has withstood the onslaught. It is part of the Kennedy Montessori School, on the east side of Kennedy, just north of 14th Avenue. The church is long gone but its two-part cemetery remains, one part on the east side of Kennedy by the Montessori, the other part across the road. Another early heritage home has been relocated a short distance west to 4011 14th Avenue, next to the Hagerman West Industrial Park, and is now the Ontario Early Years Centre.

The traffic today roars through the intersection of Woodbine Avenue and Highway 7, looking for turn signals or big-box stores, scarcely aware that there was once a quiet little hamlet at this point, surrounded by fields. Yet, on the northeast corner there was a shoemaker, George Feeley; John White’s blacksmith shop; Tom Amos’s store; and an Orange Hall. On the northwest corner, on the farm of the Brown family, after whom the hamlet was named, John Clark operated a tavern. A blacksmith shop stood on this corner, as well. Other businesses on the southwest and southeast corners were run by a shoemaker, a carpenter, and another blacksmith. A couple of sawmills operated in the neighbourhood.

Most of the intersection today is taken up with turning lanes and parking lots. The only reminder of the crossroads hamlet is the home of Alex Brown, built in 1850, and now located at 8980 Woodbine Avenue, north of the intersection with Highway 7. West of the intersection, the old church has been remodelled as the Zion Alliance Church. A short distance farther north of the intersection, Buttonville’s early main street (Woodbine Avenue) offers a well-preserved heritage landscape. (See chapter 8, on mill towns.)

West of Brown’s Corners, at the intersection of what is today Leslie Street and Highway 7, a little hamlet called Dollar struggled to survive. True to form, it contained a store, a post office, a blacksmith shop, and a church. With railways and main roads bypassing it, it remained a backwater on the landscape and a footnote in history. In the 1950s, Highway 7 was paved and later widened. Traffic increased and country homes began to appear. In 1972, the northeast corner was cleared of the last three houses for a motel, and for many years the only evidence of the hamlet was a vacant lot on the northwest corner where the store had stood. Then the suburban boom struck with a vengeance in the late 1980s and early ’90s. Today the roads have been widened even more; the farm fields have been covered with office buildings, restaurants, and stores; and prominent among them is the grandly named Times Square Richmond Hill a curving building that dominates the northwest corner housing shops and offices. Today, all memory of Dollar has gone, mostly in the name of … the dollar.