To many of us, they are Toronto’s “ghost towns”; to others, they are simply their own neighbourhoods. However Toronto’s “lost villages” are perceived, they offer visible reminders of the lost hamlets, villages, towns, and even early sites of Indigenous Peoples, that have, over the decades, been overwhelmed by the unrelenting urban growth of the Toronto area.

Human activity began with the retreat of the glaciers roughly twenty thousand years ago. Into that tundra-like landscape came the Clovis people, as anthropologists call them. They hunted species like muskox, caribou, elk, possibly mastodons, and other Arctic animals. As the climate warmed, vegetation took hold and many Indigenous groups began a culture of farming. Concentrated primarily around the area south of Georgian Bay, they lived in villages consisting of long-houses and surrounded by palisades. In their fields they grew corn, beans, and squash.

Into this landscape came the Europeans, seeking both furs and souls. Wars erupted between Indigenous Peoples looking for exclusive rights to trade furs for the pots, axes, trinkets, and guns offered by the European traders. As competition intensified during the 1600s, wars over the fur trade erupted, decimating many First Nations people, especially those farming communities of the Huron-Wendat. And what the Beaver Wars didn’t claim of the Indigenous people, imported diseases did. Evidence of early Iroquois villages have been uncovered at Baby Point on the Humber River and at Bead Hill on Scarborough’s Rouge River.

As the late 1700s and early 1800s progressed, waves of immigrants swept in from the beleaguered new American states, as well as from Britain, Scotland, and Ireland. Most of their early settlements centred on little ports and harbours. As roads were hacked into the woods, mill villages and farm hamlets began to appear. Toronto quickly grew from a newly minted colonial capital named York, laid out beside a large protected harbour.

The arrival of the railways in the 1850s drew new growth to trackside, where stations and larger divisional yards formed the nuclei of more villages. Attracted by the opportunity to ship products by rail, more industries grew where rail and water converged. The rail era began to fade after the end of the Second World War. Housing swept across the farm fields, and auto travel, the more convenient mode, replaced the passenger trains.

Through the latter years of the 20th century, developers ruled the day, turning more farmland into big-box malls and sprawling subdivisions, while condo towers soared above the Toronto skyline. The early pioneer trails evolved into the four- and six-lane car corridors of today. Heritage buildings and streetscapes held little interest for municipal politicians and developers, and history began to disappear.

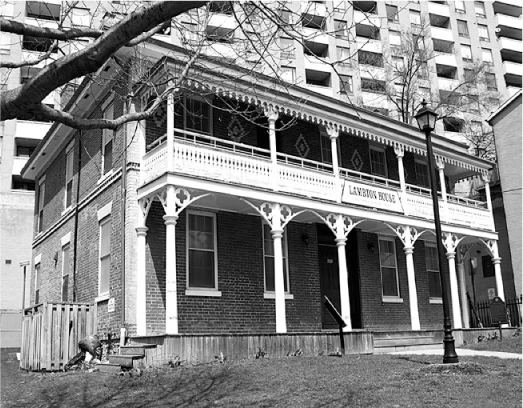

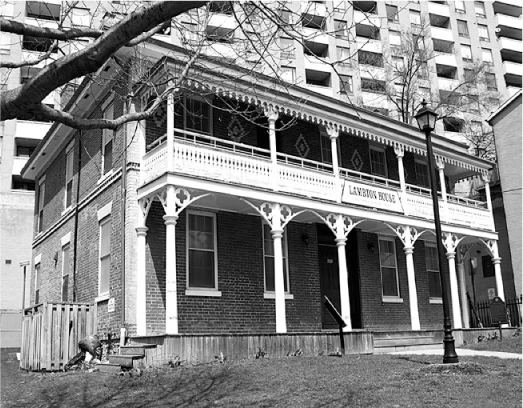

The iconic Lambton House on Dundas is one historic structure that has been rescued and restored.

Amid the chaos, there emerged a few saviours. Local historical societies began to draw attention to the vestiges of Toronto’s past; the Scarborough Historical Society and the East York Historical Society helped create museum villages, including Todmorden Mills and Thompson Memorial Park, while the Etobicoke Historical Society was instrumental in restoring the Montgomery’s Inn on Dundas West, and the North York Historical rescued the old Lambton House. (Numerous similar examples appear throughout the pages of this volume.)

Business Improvement Associations (BIAs) also began to realize the commercial value of preserving and celebrating their various heritage main streets and buildings. The Islington BIA is now leading walking tours of its heritage main-street murals.

Other “ghost villages” have morphed into trendy neighbourhoods, such as Leslieville, Cabbagetown, and Yorkville. In a few instances, entire historic villages have been designated as “heritage districts.” Most noteworthy are Buttonville, Old Meadowvale, and Churchville. Others, despite being overwhelmed by the city’s relentless growth, carry on … West Toronto Junction, East Toronto, and New Toronto are cases in point.

As a result, hidden in the congestion and sprawl that marks much of Toronto, we may yet find traces of Toronto’s past.

This volume (in which I have revisited and updated the 1997 version) presents an opportunity to explore a city to find that evidence of a distant legacy; these are Toronto’s lost villages.