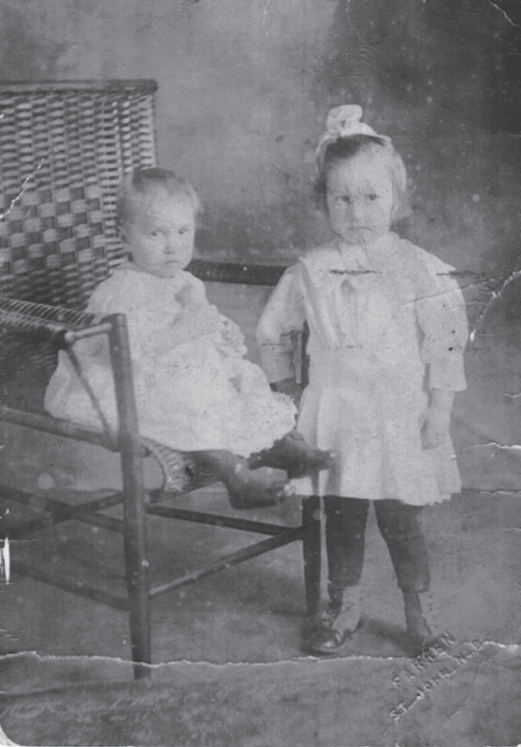

Figure 1.1 • Eldon Rathburn, age two, with sister Inez, Farren Studio, Saint John, ca. 1918.

Formative Years

From Saint John to L.A.

Early Life in Saint John

Eldon Davis Rathburn’s New Brunswick ancestors were descended from United Empire Loyalist stock. Joseph Rathbun (1745–after 1800) fled to Canada from Rhode Island in April of 1783, at the time of the Revolutionary War. Considered one of the “Loyalists of the spring fleet,” Rathbun received a land grant of one thousand acres from the Crown for his loyalty, in Queen’s County, New Brunswick. (Rathburn’s descendants changed the family surname from Rathbun to Rathburn in the early nineteenth century, though why or precisely when remains unclear.) Subsequent generations of Rathburns settled the area surrounding Pleasant Villa, Queen’s County, where Eldon was born on 21 April 1916.1 He was given his middle name in honour of his paternal grandmother Elethear Davis (1865–1917), whose husband George Rathburn (Eldon’s grandfather) once “drove the mail on Gagetown and Westfield”2 and later established a grocery business in the north end of Saint John, the province’s rapidly growing centre of fishing and shipbuilding. Caleb Davis Rathburn (1888–1944), Eldon’s father, drove a delivery team for the Irving Oil company, and sold insurance. Following in his father’s footsteps, Caleb came to own a small grocery business, and ran it with one employee and Eldon’s mother Blanche (née Puddington, 1891–1985).3 Caleb Rathburn also collected income from a few low-rent properties he had purchased in Saint John. Blanche also sold Avon products, took in boarders, and managed room rentals during the busy Saint John winter shipping season, when the Saint Lawrence passage to Montreal had become inaccessible. While balancing her many responsibilities, Blanche also tended devotedly to her two children, Eldon and his older sister Inez (1914–1988).

Eldon displayed musical talent at an early age, and although providing music lessons for the children represented a significant sacrifice for the family, Blanche Rathburn felt strongly about supporting the development of their talents. Eldon recalled his mother listening to 78 rpm recordings of classical music on the old family gramophone – he recalled Strauss’s “Blue Danube Waltz” and Rubinstein’s “Melody in F,” among other household favourites – and accompanying herself on the family’s Willis piano, singing popular Tin Pan Alley tunes such as Eddie Cantor’s “Oh Gee, O Gosh, Oh Golly, I’m in Love” (1923), a humorous but suggestive and “naughty” song in Eldon’s view.4 The piano had been purchased by Eldon’s parents for Inez,5 but when the precocious young Eldon “held his hands over his ears because he didn’t like the way she played,” his parents eventually relented and arranged for his lessons.6 He received his first piano lesson at the age of six, from a “Mrs. Craft,” who taught him until the age of nine using “the New Bellak method” (published in 1874).7 While Mrs Craft may have provided Eldon with foundational skills as a pianist, he later remembered her only in unflattering caricature: “cross-eyed, moustache, bad breath.”8 Although he always practised diligently and was intensely proud of being a musician, Eldon initially had concerns about how his piano studies might be perceived in his community. The prevalent view in Saint John during the 1920s, he recalled – among men in particular – was that the piano was an “effeminate” instrument.9 Don Messer’s biographer Johanna Bertin confirms this perception: “Rathburn was a rarity in New Brunswick … men played the violin and women played the piano.”10 A Wurlitzer Pianos ad in the October 1927 issue of Étude Magazine fully captures this gender stereotype: “[the Wurlitzer is] a mother’s choice … for her daughter’s happiness!”11 Blanche’s protectiveness and devotion to Eldon’s musical talent may have further exacerbated his concerns. She was known to have prevented Eldon from cutting wood “for fear that he might hurt his fingers.”12

Eldon attended Dufferin Elementary School (1923–27) and King George Public School (1927–30) as a child. During his teenage years he studied at the Saint John Vocational School (renamed “Harbour View High School” in 1997), a historic New Brunswick high school with a long and distinguished list of alumni including painter Jack W. Humphrey,13 painter Frederick J. Ross,14 journalist Charles Lynch, and “Stompin’ Tom” Connors, the iconic Canadian country and folk singer-songwriter. At SJVS Eldon came under the influence of William Comerford Bowden (1873–1959), a teacher who would have the most important formative influence on the young composer. “W.C.” Bowden was a well-known musician, conductor, and educator in the Saint John music community during the first half of the twentieth century. Upon graduating from Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music in 1899, Bowden accepted a staff teaching position at the Saint John High School, Canada’s oldest publicly funded secondary school.15 In 1930 he moved to the Saint John Vocational School, where he taught until his retirement in 1956. An accomplished violinist and an expert luthier, Bowden directed high school orchestras in Saint John for more than fifty years and established a number of string quartets in the Saint John area. His output as a composer was modest, but he published two string quartet movements with Ditson & Co. of Boston.16 As a musician and teacher, Bowden was known for his interest in theoretical matters. In the October 1927 issue of Étude Magazine he published one of the first explanations of equal temperament to appear in print in North America.17 He also served as secretary of the local chapter of the Musicians’ Union for a decade.

Figure 1.2 • Jack Weldon Humphrey, Old Musician – Professor Wm. Bowden, 1958.

With Bowden’s guidance and encouragement Eldon wrote Intermezzo (1933), an orchestral work (his first) “written very much in the style of Victor Herbert.”18 Intermezzo was first performed by the Saint John Vocational School Orchestra, conducted by Bowden, between acts in the school’s May 1933 theatrical production of Hamlet,19 and later that year it was performed again at Eldon’s convocation ceremony.20 Bowden’s letters to Rathburn reveal how deeply he believed in the young composer’s talent.21 “I have the greatest faith in you,” he wrote to Eldon some years later, “[and I] know that you will come out on top as I have always predicted, even from the day you wrote me that Intermezzo – remember?”22 Toward the end of his life, Bowden proudly cited Eldon’s accomplishments at every opportunity. When he retired from teaching in 1956 he told a reporter: “I taught him harmony … [and] now he’s one of the greatest modern composers; we’ll have something really big from that boy.”23 Bowden’s octogenarian dignity shines through in a 1958 portrait painted the year prior to his death (figure 1.2). The portraitist was SJVS alumnus Jack Weldon Humphrey, who had played under Bowden’s baton in the string section of the Saint John Symphony Orchestra during the 1950s.

Early twentieth-century Saint John witnessed a landmark event in the history of cinema. By the turn of the century, travelling vaudeville troupes were visiting the Maritimes less and less frequently due to the cost of transporting the performers. According to the indefatigable Walter Golding, an entrepreneurial Saint John theatre manager during the period, “motion pictures were brought in to help pay the rent, but it was not expected that they would be anything more than a passing novelty.”24 According to some film historians, when Golding hired a small live orchestra to accompany silent films at the Nickel Theatre on Saint John’s Carlton Street in May of 1907, he was among the first to do so.25 For the next twenty-five years, at movie houses throughout North America and around the world, pianists and small bands and orchestras would be hired to accompany silent films, to enhance both the film’s action and emotional impact and to mask the sound of the projector.

Figure 1.3 • Imperial Theatre, Saint John, New Brunswick, ca. 1915.

“The Nickel” closed in early 1913, but on 19 September 1913 Golding opened the Imperial Theatre with much fanfare. It was built by the Keith-Albee vaudeville chain along with their Canadian subsidiary, the Saint John Amusements Company Ltd.26 Billed as the “Finest Theatre in Eastern Canada,” the Imperial would become something of a second home for Eldon, as it did for three other important figures in movie history who spent their childhoods in Saint John: Hollywood mogul Louis B. Mayer (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer),27 MGM film star Walter Pidgeon,28 and the celebrated Canadian film actor Donald Sutherland.29 Golding continued as the theatre’s manager until 1945. In addition to Hollywood film, he brought many of the biggest names in the entertainment business to the Imperial, including actress Ethel Barrymore, John Phillip Sousa (“the March King”), and the illusionist Sir Henry Lauder, better known by his stage name “Harry Houdini.”30

During his high school years Rathburn first developed what would become a lifelong fascination with the music of the cinema. Bowden had done some work at the Imperial theatre as a pianist, conductor, and arranger for silent film, and Eldon had aspired to follow in his footsteps:

[The Imperial Hotel] had a fourteen-piece orchestra with a Wurlitzer organ for silent films that was really impressive. In the back of my mind, I would have loved playing for silent films. I was always aware of the music … [and] I had some of the music by composers who wrote for the silent films. I have a cue sheet from the old days for “Robin Hood” and I remember watching how the orchestra cued the music from dialogue cues … I was sort of brought up hearing film music. I’d come home and my mother would say, “How was the show?” And I’d say, “I don’t know. I was too busy listening to the music.”31

When “the talkies” arrived at the Imperial Theatre, Eldon lamented the loss of silent film and its accompanying musicians. “The orchestras were fired,” he recalled in conversation with Louis Hone in 1993, “which was too bad.”32 Rathburn also recalls this formative moment in biographical notes penned into his notebook: “I remember the silent films and had the ambition to be a movie pianist; the coming of the sound film put an end to that.”33 It is clear that Eldon’s lifelong fascination with the immense power of music to enhance and complement moving images on the screen had taken seed in the darkened Imperial Theatre during the 1920s.

The Professional Musician in Training: 1933–1938

Following his graduation from SJVS, Eldon continued piano studies with “professor” William Davis. Davis’s pedagogical influence seems to have been minimal, and Eldon studied with him only briefly. He would recall Davis in later years as “a very nice man: a dwarf, quite blind, who wore a cap, used a cane and used Czerny Op. 261 and Op. 299 in his teaching.”34 From Davis he moved to the teaching studio of Mrs A.H. Campbell, under whose tutelage he would ultimately complete a licentiate in piano with the McGill University Conservatorium of Music. During his last year in high school and continuing for a period of five years until 1937, Rathburn also pursued organ studies with Eric Rollinson, an organist-choirmaster and music teacher who had recently moved to Saint John from London, England.35

Figure 1.4 • The New Brunswick Lumberjacks in the CFBO radio studio (later CHSJ), ca. 1929. Left to right: Maunsell O’Neil (a.k.a. “Joe Leblanc”), Eldon Rathburn (seated at the grand piano, age fourteen), Don Messer, James MacAusland, and Roy DuPlacey. Messer provides the following caption for this scrapbook photo: “first photo of the group, taken in a radio station.”

Eldon met Don Messer, the legendary Maritime fiddler, while still a student at SJVS. Apparently impressed with the teenager’s talent, spirit, and pianism, Messer invited him to join his touring band, performing music Messer described as “not Western or cowboy music” but rather “folk tunes that have been around for two or three hundred years … passed from generation to generation.”36 From his final year in high school through to 1936, Eldon performed, broadcast, and toured with a combo that would later become known as “Don Messer and the New Brunswick Lumberjacks.”

Surrounded by Messer and his combo and dwarfed behind his grand piano, a very young Eldon Rathburn appears in an early photo of the combo – shown in figure 1.4 – taken circa 1929 in the Saint John CFBO radio studio (later CHSJ, the local CBC outlet).37 Some of Messer’s radio broadcasts were aired nationally, while others were broadcast only regionally.38 Messer also travelled widely throughout the Maritimes and New England, playing for dances in small rural communities far and wide.39 Life on the road could be gruelling, and more than once during these years Eldon arrived home from a tour with Messer and walked straight to a piano lesson, whereupon his teacher sent him directly home as he was falling asleep at the keyboard.40 “I was leading a kind of double life in those days,” he recalled in later years, “playing in a dance band all night and then trying to play Schumann at 10:00 a.m. the next morning!”41

Figure 1.5 • Don Messer and the New Brunswick Lumberjacks (1935). Front left to right: Maunsell O’Neil (a.k.a. “Joe LeBlanc”), Don Messer, Eldon Rathburn (age nineteen), Ned Landry, Wallie Walper. Back row: Jim MacAusland, Sammy Cohen, Julius “Duke” Neilson.

Messer’s band included some notorious characters. Once a circus performer, bassist Julius “Duke” Neilson, often injected his fire-eating routine into the band’s appearances as “Julius, the human volcano.”42 Fiddler Maunsell O’Neil was widely known as “Joe LeBlanc,” after his comic CBC radio personification of an Acadian lumberjack.43 Singer and guitarist Charlie Chamberlain, billed as “The Singing Lumberjack,” was the only band member who had actually worked in a lumber camp.44 Filling out the group in the early years were drummer James McCausland, plectrum banjoist Roy DuPlacey, and fiddler and harmonica player Ned Landry, Stompin’ Tom Connors’s cousin, who would become renowned as a fiddle recording artist for the RCA label. Eldon learned to mix light-hearted good humour with music making at an early age.

These were halcyon days for Eldon. Years later he wrote to Messer’s reedman Sammy Cohen: “I keep thinking of the old days … long trips with Don Messer etc.… lots of memories of our trips to Boston, the old Harvard, etc.”45 Messer’s detailed bookkeeping and notes taken during these tours reveal that the Lumberjacks travelled 5,900 miles during the summer of 1935 alone. For most shows, Eldon earned approximately $2.50, a solid fee for a musician during the Great Depression.46 However, with accommodation costing approximately $0.70/night, and meals totalling approximately $1.40/day, Eldon generally returned from these tours with countless stories of the band’s adventures and shenanigans, but with empty pockets. He was devoted to Messer and the band for the experience, the camaraderie, and for what he was learning from the musicians around him. The year 1936 was a particularly successful one for Messer and the Lumberjacks. Selected to represent New Brunswick at the annual summer New England Sportsmen’s Show, and heralded in the Boston press, they gave a number of performances and radio broadcasts there, success that only further bolstered their reputation in Saint John and throughout eastern Canada.47 During these years Eldon accepted other accompaniment work of various kinds and any other opportunities that arose to play for remuneration. He appears never to have been employed in a job that was not directly related to music, an extraordinary fact given that these were depression years.

The period 1936–38 seems to have been a turning point for Eldon. In late 1936 he took leave from Messer’s band in order to undertake a licentiate in piano performance at McGill University, and he played only sporadically with Messer during this period.48 In 1937 he accepted a position as organist at the Saint John Stone Church, where his duties included conducting weekly choir rehearsals, choral arranging, providing music leadership for the church’s Anglican worship services, and playing for weddings and funerals, which provided him with an additional income supplement. On 6 October 1937, Eldon completed a licentiate in classical piano performance from the McGill Conservatory.49 The year 1937 brought cause for celebration of another kind to the Rathburn home. On New Year’s Eve, when both Blanche and Caleb were in their late forties, and Eldon and Inez were ages twenty-one and twenty-three respectively, Joan Rathburn was born. Joan’s arrival brought not only great joy to the entire family but also new sets of responsibilities at a time when war clouds were gathering on the horizon.

Nineteen thirty-eight was a banner year for Eldon. In 1937 he had submitted two compositions, a two-piano work titled Silhouette (1936) and an art song titled To a Wandering Cloud (1938), to a nationwide Canadian Performing Rights Society competition endorsed by the Governor General of Canada. The names of the competition winners were announced on 15 April 1938, and reported in the Winnipeg Tribune the next day:

Eldon D. Rathburn, 21, of Saint John, N.B., won the $700 scholarship of the Toronto Conservatory of Music, offered by the Canadian Performing Rights Society for musical composition, it was announced … by Sir Ernest MacMillan, chairman of the selection board. Each entrant in the Dominion-wide competition was required to submit two musical compositions, one of which had to be a song. The winning compositions were “Silhouette for Two Pianos,” and a song, “The Wandering Cloud.”50

On 2 May 1938, John Buchan – Lord Tweedsmuir and Governor General of Canada – presented Eldon with the prestigious Canadian Performing Rights Society grand prize in an Ottawa ceremony held at Rideau Hall. An Ottawa Journal article listed the other winners: Frances Campbell and Louis Applebaum of Toronto, together with Leonard Basham of Vancouver, each of whom won cash awards of fifty dollars. An additional cash prize of twenty-five dollars was awarded to the eleven-year-old Clermont Pépin of La Beauce, Quebec. Pépin’s submission had so charmed the judges that they created a special juvenile class to provide him with encouragement.51 The prize winners were accommodated in style, together with Lord Tweedsmuir and other guests and dignitaries, on the steps of Rideau Cottage.

The Canadian Performing Rights Society Scholarship enabled Rathburn to pursue his studies at the Toronto Conservatory of Music during the 1938–39 academic year. In Toronto, Eldon studied piano with Reginald Godden, organ with Charles Peaker, harmony with Leo Smith, and composition with Healey Willan. Any reverence Eldon may have once had for Willan could not have run deeply, and he rarely reflected on his year in Toronto later in life. Unlike Willan, and notwithstanding his own experience as a church organist, Eldon was never particularly interested in writing sacred and vocal music. The aesthetic gulf between the young composer-pianist who had spent several years touring with the New Brunswick Lumberjacks, and the elder Willan, the “éminence grise” of British-Canadian sacred music, was undoubtedly wide. It is perhaps not surprising that little more than ten years later Rathburn would be among the first composers nationwide to join the fledgling Canadian League of Composers, an organization that was privately known among its members as the “League against Willan.”52

Figure 1.6 • Canadian Performing Rights Society composition prize winners with Governor General John Buchan (Lord Tweedsmuir), judges, and guests at Rideau Hall, Ottawa, 2 May 1938. Front row: Ms G. Dionne (Clermont Pépin’s teacher), Eldon Rathburn ($750 scholarship winner), Clermont Pépin ($25 prize winner), Frances Campbell ($50 prize winner), Godfrey Hewitt (member of the CPRS adjudication panel). Back row: Louis Applebaum ($50 prize winner), Hector Charlesworth (member of the CPRS adjudication panel), Governor General John Buchan (Lord Tweedsmuir), Henry T. Jamieson (Scottish Olympic athlete and CPRS president). Photo by Yousuf Karsh.

The War Years

Following successful organ studies with Eric Rollinson in Saint John and Charles Peaker in Toronto, Eldon hoped to complete his ARCO certification with the Royal College of Organists in 1939. In January of that year he wrote the paperwork component of the exam in Toronto,53 and in February he received a letter from the RCO informing him that he had passed. When he returned home from Toronto in the spring of 1939, Eldon accepted a new position as organist and choirmaster at Saint John’s Main Street Baptist Church, a job he would hold until the end of the war. On 1 September 1939 Hitler’s forces invaded Poland and the United Kingdom and France declared war on Germany the following week. Canada was suddenly plunged into the war effort when Mackenzie King’s government followed suit within days. In 1939 Eldon applied to the Royal Canadian Air Force to report for service, and at age twenty-three he was an appropriate age for enlistment. However he was ultimately deemed “unable to measure up to the high standard of fitness required for entry into the RCAF under existing regulations.”54 Enclosed with the RCAF’s reply was a medical certificate indicating that Eldon was not required to report for military training, due in large part to his poor vision. Since his RCO organ performance and ear-training exams would have involved travel to England, the outbreak of war also put an end to those ambitions.55

During the late 1930s and throughout the war years, Eldon collaborated closely with Bruce Holder Sr (1905–1987), a figure who would rise to such prominence in New Brunswick that he came to earn the nickname “Mr. Music of Saint John.”56 During a remarkable career spanning six decades, Holder was a well-known band and orchestral musician in Saint John, just as his father Fred Holder had been for the generation before him, and his son Bruce Holder Jr would be for the next.57 Like Eldon, Holder had been a student of W.C. Bowden at SJVS during the 1920s, and a violin student in his private studio. And like Bowden, he presided as concertmaster over both the Imperial Theatre Orchestra (1920–29) and the Saint John Symphony Orchestra (sjso).58 Having studied conducting with Pierre Monteux at the renowned French conductor’s annual summer school in Hancock, Maine, Holder would later become conductor of the sjso (1954–58).

During the war years, Holder created and directed a twenty-five-piece orchestra that gained widespread renown throughout Canada and the US. The Bruce Holder Orchestra recorded and broadcast live from a studio on top of the luxurious Admiral Beatty Hotel on Saint John’s historic King Square, beside the Imperial Theatre. These were the last years of the “Golden Age of Radio,” a time when radio provided an escape, an important source of news updates from Europe, and an entertainment lifeline for the entire North American population.59 With his orchestra, Holder created a series of popular radio broadcasts, variously titled Fundy Fantasy, Fundy Follies, Fundy Frolic, Fanfare, Show Shop Songs, Music You Like to Hear, Holiday for Strings, and Music Styled for Strings, programs that were carried on CFBO, CHSJ, and nationwide on CBC radio, as well as on the Mutual network in the US. For the younger generation at the time, Holder was perhaps best known for his lively wartime dance band that attracted revellers to the ballroom of the Admiral Beatty Hotel on Saturday nights, from all over eastern Canada and beyond.60 From 1937 to 1947 Eldon was the go-to pianist and arranger for Holder’s radio orchestra and dance band.61 Rathburn’s arrangements and rare talent and stylistic versatility as a pianist are given prominence on dozens of recordings made for broadcast with the Bruce Holder Orchestra, including arrangements of popular tunes such as “The Chauffeur and the Debutante,” “Czardas,” “Skylark,” “Cornish Rhapsody,” “Theme from the Warsaw Concerto,” and the “Jalousie Tango.”62 Reflecting on this period of his life in later years, Eldon spoke of many sleepless Saturday nights playing with the band at the Admiral Beatty Hotel, followed by early Sunday morning responsibilities leading the choral and worship music at Saint John’s Main Street Baptist Church.63 It is clear that Eldon was held in high esteem by the entire community of musicians around him during these years. Verdun (“Speedy”) Wilcox, a trombonist who had been a regular with Holder’s orchestra (and had also played with Eldon in the high school orchestra during the early 1930s), remembered him fondly: “[Eldon was] a fabulous person, both musically and in other ways. He was terrific. He could do it all. Eldon was the guy. Unlike some of the older musicians back then, he had no problem with booze. He didn’t even smoke. Everybody liked him!”64

On 20 February 1940, the Canadian Performing Rights Society sent a telegram to Rathburn, requesting a summary of his biography for use in the introduction to a forthcoming CBC national “Canadian Snapshots” broadcast of a CBC-commissioned orchestration of his Silhouette (1938, originally scored for two pianos) on 6 March 1940.65 In a biographical paragraph accompanying Eldon’s letter of reply, dated 27 February 1940, he describes himself as a “piano soloist and musical arranger for the CBC, as well as a church organist.”66 He singles out Bach and Debussy as his “favourite composers” at the time, and José Iturbi – an actor-pianist who appeared in a number of celebrated Hollywood musicals during the 1940s – as his “favourite pianist.”67 Eldon also mentions that in 1940 his most immediate compositional goal was to write a concerto for piano and orchestra. Circumstances would take him in other directions, however, and writing a piano concerto was an early ambition that he would never fulfill during his long career.

In 1941, still in his early twenties, Eldon experienced a new form of affirmation as a composer when his Union-Jack-waving patriotic ditty titled “Mr. Churchill, Our Hats Are Off to You,”68 a song co-written with Holder and vaudevillian lyricist Dave Marion Jr, was published by Gordon V. Thompson Ltd of Toronto.69 The song sold so well that it was later included in The Happy Gang Book of War Songs, a compilation of tunes that had been performed on-air by “The Happy Gang,” the wildly popular radio troupe whose CBC lunchtime variety show attracted as many as two million listeners daily during the war and early postwar years.70 In Marion’s clever lyric, Churchill has “that Nelson spirit.” He’s the one “the Nazis cannot bluff … he’ll make them cry ‘we’ve had enough’!” The song ingeniously incorporates a melodic passage from the refrain of “There’ll Always Be an England,” a tune made popular by Vera Lynn at the outbreak of the war. An excerpt from the preface to the “Happy Gang” compilation both captures the prevalent mood in wartime Canada and hints at a new trend toward government “instrumentalization” of the arts, one that would continue to prevail in Canada after the war:

Governments have recognized the morale-building value of wartime music. They have found that music inspires, cheers, and inspires efficiency. The Happy Gang has a unique mission in maintaining Canada’s morale. For many weeks they sang “There’ll Always Be an England” on every program, day after day, and are largely responsible for the song’s tremendous vogue. No one can estimate its value to Canada during the critical days of 1940 when England stood alone against the might of martialed tyranny.71

On 20 November 1944, Eldon’s father died in Saint John of colon cancer, at the age of fifty-six. At the funeral service Eldon accompanied a large choir and soloist in a rousing rendition of “Nearer My God to Thee,” and expressions of tribute and sympathy poured in from individuals and organizations far and wide, including the choir of Main Street Baptist Church, O.S. Dykeman & Son Grocers, and the Sammy Cohen and Bruce Holder orchestras.72 Caleb Davis Rathburn was laid to rest in the cemetery of St Stephen’s Anglican Church, Queenstown. At age twenty-eight, and with his sister Inez now married to William Cooper and raising her family in Victoria, BC,73 Eldon was suddenly the primary wage earner in the Rathburn household, with full responsibility for the care of his mother Blanche and seven-year-old sister Joan.

Figure 1.7 • “Mr. Churchill, Our Hats Are Off to You.” Music by Eldon Rathburn and Bruce Holder, lyrics by Dave Marion Jr.

Hollywood Bound

With the war still raging in Europe and the sorrow of the loss of his father still fresh, Eldon had one of the most exhilarating and formative experiences of his life. During the last few years he had been working steadily on a new piece for orchestra titled Symphonette. From the moment of its conception Eldon had planned to submit his new piece to one of the many competitions that had sprung up during the war years to encourage young composers. But he felt that he was still very much a novice composer, and was therefore not optimistic that his work would be well received. Although he began to study orchestration in earnest the very day he graduated from high school in 1933,74 and was very much “under the spell of Shostakovich’s First Symphony,” he “still had no real idea about certain things, especially writing for violins and the other strings.”75 In 1943, after submitting his Symphonette to a competition adjudicated by the recently knighted Sir Ernest MacMillan, Eldon was deeply disappointed when MacMillan returned the manuscript to him with no accompanying letter, no comment, and no indication that it had even been reviewed as an entry. Undeterred, “just for fun,” Eldon also submitted his Symphonette to a prestigious competition in Los Angeles in early 1944 when he “saw a notice in Étude Magazine about the contest.”76 The L.A. Philharmonic Young Artists’ Competition was co-sponsored by the orchestra in partnership with the Southern California Symphony Association, Earle C. Anthony Inc., and the Los Angeles Daily News. The contest had received more than one hundred submissions from every corner of North America, and competition was intense. Its panel of adjudicators was chaired by the renowned Austrian-American composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951), friend of Gustav Mahler, teacher of Alban Berg and Anton Webern, and arguably the most influential composer, music educator, and music theorist of the twentieth century. Schoenberg was joined on the panel by Arthur Lange (1889–1956), the American bandleader and a prolific composer of popular song and Hollywood film music, and by the Jewish Polish-French composer Alexandre Tansman (1897–1986), who had found himself exiled in Los Angeles after fleeing Europe in 1941. Schoenberg, Lange, and Tansman shortlisted ten submissions, from which the final selection was made. The prize was a premiere performance by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, and $500 in War Bonds.77 In a telegram dated 27 March 1944 and a letter dated 29 March, the jury informed Rathburn of its decision to award First Prize to his Symphonette. Schoenberg described the panel’s decision as follows: “The award was given to Mr. Rathburn unanimously by Mr. Tansman, Mr. Lange and myself. His Symphonette was among the great number of applicants by far the best, and has in addition to that qualities of merit of its own. It shows personality, sense of form and logic, true inventiveness and serious elaboration.”78

New Brunswickers were elated when Eldon’s prize was announced in the Saint John Telegram. Not only had Eldon conquered Los Angeles, the burgeoning centre of the new film and entertainment universe, but his orchestral score had wowed an esteemed panel of judges with international reputations. When the euphoria wore off, however, it was followed by anger and frustration in some circles. The incident with Sir Ernest MacMillan, who had seemingly ignored the same score in a Canadian competition held the previous year, touched a raw national-unity nerve in New Brunswick. A similar incident had occurred in 1942, when at the height of the war in Europe, an Ottawa Journal article warned of another war that was brewing in New Brunswick, closer to home. A growing sentiment of alienation among eastern Canadians came into full view, the article reports, in response to a perceived snub when Hollywood film star Anna Neagle was invited by the federal government to tour central Canada, but not the Maritimes: “Maritimers, normally mild and amiable, are good and mad … Saint John itself, it says, is evidence that political bonds can be shattered by centralization of control … Settlement by United Empire Loyalists and the subsequent breaking away from Nova Scotia are proof that New Brunswickers will stand just so much and no more … We have been warned.”79

While a deep and abiding sense of Canadian national pride has always been strong among New Brunswickers, Maritimers also have a proud history of marching to their own drummer, and their national patriotism has never been one that takes its lead from central Canadian elites. Rightly or wrongly, the general feeling conveyed by Sir Ernest’s seeming indifference to Rathburn’s music – in stark contrast to the laudatory reception it received in Los Angeles – was that Toronto viewed New Brunswick as something of a musical backwater, unworthy of much notice. In a letter to the editor submitted to the Saint John Telegraph-Journal in April 1944, author Elizabeth V. Munro expressed her contempt for what she considered to be a faux pas by the Toronto judges.80 She tried to reassure Eldon in a follow-up letter dated 26 April 1944 that “there is nothing in [my letter to the editor] which will jeopardize your position with these honorable dumbells, as I have tried to keep it purely an impersonal affair.”81 Her goal, she wrote, was to “let them know there is something cooking in Maritime music.” She closes her letter with words of encouragement for Eldon: “Keep up the good work … We are counting on you to show them up there that while they may ignore us to their heart’s content, they can’t keep us down.”82 She enclosed her letter to the editor of the Telegraph-Journal:

Saint John is enjoying a hearty chuckle these days, particularly in musical, literary and artistic circles where although the thing has happened many times before, it is still a source of never-ending amusement. It appears that the brilliant young Saint John musician, Eldon Rathburn, entered a symphony in a Toronto contest recently, as much with the hope of receiving a word or encouraging criticism from the presumably higher-ups in the musical world, as with any thought of winning the prize. Back came the symphony, accompanied by the musical equivalent of an editor’s rejection slip, and without a word of comment. Apparently they considered it unworthy of even that slight notice. Disappointed, but not undaunted – Maritimers die hard – Mr. Rathburn promptly sent it off to an International competition being sponsored in California, where – you guessed it – it won First Prize. Over a large entry of Canadian and American competitors alike. We understand it will have its premiere next year under the distinguished baton of Alfred Wallenstein. Where it will go from there, it is not possible to predict, but American conductors do not include on their programs symphonies by young Canadian composers purely on the basis of the Good Neighbour policy. A work must stand on its own merit to warrant much recognition. This is not the first time that Saint John has been able to thumb its nose at Toronto judges and it probably won’t be the last. Nor is the proclivity for having the last laugh always confined to the Maritimes. We understand that a young composer from Quebec had a similar experience some years ago, and one of the Toronto judges tried to cover up afterwards by saying: “It might be good enough for the United States, but it isn’t good enough for Canada.” Well, naturally we are all for high standards in Canadian music, but it is an incontrovertible fact that Canadian composers – not to mention poets and writers – have to go to the United States to gain recognition. After which, Canada proudly hails them as native sons. There may be a few exceptions to this rule, but sad to relate, Maritimers are not among them. And in Toronto – that Jerusalem of Canadian arts – the High Priests continue to look at one another blankly and say: “Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?”83

Figure 1.8 • Photo published in the L.A. Daily News (22 March 1945), captioned “Winners in Prize Winning Series Rehearse with Director: Composer Eldon Davis Rathburn, director Alfred Wallenstein, pianist Gloria Greene.”

Munro’s drafted letter to the editor was not published in its entirety, perhaps due to its vitriolic and none-too-thinly-veiled attack on Sir Ernest MacMillan et al., to Eldon’s tender age, and to the political sensitivity of the Maritime alienation issues it was raising at the height of the war.

Although he had never been farther away from Saint John than Boston, the following spring Eldon travelled by train to California to attend the premiere performance by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, at Philharmonia Auditorium, under the baton of conductor Alfred Wallenstein. The Los Angeles Daily News published a photo of Rathburn with Wallenstein and the young pianist Gloria Greene, a second L.A. Philharmonic award winner.84 On 24 March 1945, the day after of the premiere performance, the Daily News published an encouraging concert review:

[The featured] attraction on the program was the prize-winner Eldon Davis Rathburn’s “Symphonette” in three parts. Rather ambitious in scope for a young composer, Rathburn’s composition was divided into a somber first movement, a romantic, elegaic second movement and a more swiftly moving finale. Although the work does not as yet indicate the composer’s style … a seeking for orchestral color is evident. Whether or not it will stand on its merit, the “Symphonette” has had a hearing and this is important in the life of any aspiring composer.85

Rathburn’s 1945 sojourn to Los Angeles and his visit to Schoenberg’s Rockingham Avenue home were of pivotal importance in his life and career. We will return to them in more substance in chapter 5.