Here are a number of medicinal plants found in states west of the Mississippi and primarily in the Mountain West.

Asteraceae (Arnica montana L.; A. acaulis Walt; A. cordifolia Hook; A. latifolia Bong.)

Identification: Perennial that grows to 18”. Rhizome is brownish. Leaves form a basal rosette. Hairy stem rises from the rosette and has 2–6 smaller leaves, ovate to lance shaped and somewhat dentate (toothed). Terminal yellow flowers emerge from the axil of the top pair of leaves. Flowers are 2”–3” in diameter and have a hairy receptacle and hairy calyx. Tiny disk flowers reside inside the corolla and are tubular; there are as many as 100 of these disk flowers per flower head. Some variation between species.

Habitat: Typically in the shady mountainous areas, along seeps and stream banks to 10,000’, and in wet alpine meadows.

Food: Not edible; toxic—internal consumption causes stomach pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. High doses may induce cardiac arrest.

Traditional uses: Flowers and roots have been used to treat bruises; to relieve sprains, arthritic pain, muscle ache; to heal chapped lips; and to treat acne. Volatile oils in the flowers used in making perfume. Native Americans used an infusion of the roots externally for back pain. A poultice was used on edemas to reduce swelling. The plant was considered anthelmintic, antiseptic, astringent, choleretic, emmenagogue, expectorant, febrifuge, stimulant, and tonic, and was used as a topical agent for wound healing. The whole plant, used after extraction in ointment or as a compress, has antimicrobial and fungicidal action. In folk medicine, the plant was used to induce abortions.

Modern uses: Arnica preparations include tinctures, salves, lotions, and crushed or bruised plant placed externally on arthritis, bruises, muscle sprains, and strains. Theoretically, healing or comfort is induced by improving circulation to injured area. Commission E, the German compendium of therapeutic herbs for human use, approves arnica preparations for treating fevers, colds, skin inflammations, coughs, bronchitis, mouth and pharynx inflammations, rheumatism, injuries, and tendencies toward infection (weakened immunity). Medicinal parts include the roots and rhizome, dried flowers, and leaves collected before flowering. Because of the toxic nature of the plant, homeopathic doses are used to manage pain, to treat diabetic retinopathy, and to treat muscle soreness. The plant extract is used in antidandruff preparations and hair tonics. In a few clinical trials, arnica presents mixed results as an anti-inflammatory. Other studies show it may be an effective anti-inflammatory and may reduce pain after exercise (see Memorial Sloan Kettering 2014).

Notes: Arnica species are abundant in the Mountain West from the Little Bighorns through the Rockies and on into the Pacific Northwest. They are numerous in and around the slopes of Mount Rainier, Mount Adams, and Mount Baker in the Cascades of Washington State.

CAUTION: Flowers may be a skin irritant, causing skin reddening or eczema. Do not use during pregnancy. Do not use if sensitive (allergic) to members of the daisy family. Health-care practitioners warn not to use arnica on mucous membranes, open skin wounds, or the eyes. Do not use orally except in homeopathic concentrations. Arnica may interact with anticoagulants and induce bleeding.

Asteraceae (Balsamorhiza sagittata Pursh Nutt.)

Identification: Leaves are basal with a thick, tough petiole, arrow-point shaped, hairy, and rough to the touch, 8”–20” in length. Flowers are yellow, long stalked. Up to 22 yellow rays encircle the yellow disk of florets. Whole plant is 1’–2’ in height.

Habitat: Along banks and dry washes of foothills and higher elevation of the Rockies from Colorado to British Columbia on dry, sunny slopes.

Food: Young leaves and shoots are edible, as well as young flower stalks and young stems. They may be steamed or eaten raw. Peeled roots are edible but are bitter unless slow-cooked to break down the indigestible polysaccharide (inulin). The roots may be cooked and dried, then reconstituted in simmering water before eating. Pound seeds into a meal to use as flour or eat out of hand. The roasted seeds can be ground into pinole. The Nez Perce Indians roasted and ground the seeds, which they then formed into little balls by adding grease.

Traditional uses: Native Americans used the wet leaves as a wound dressing and a poultice over burns. The sticky sap sealed wounds and was considered antiseptic. Although balsam root is bitter when peeled and eaten, it contains inulin that may stimulate the immune system, providing protection from acute sickness such as colds and flu. The sap was considered antibacterial and antifungal. A decoction of the leaves, stems, and roots was sipped as therapy for stomachaches and colds. The root also used for treating gonorrhea and syphilis. In the sweat lodge, balsam root smoke and steam were reported to relieve headaches. The smoke from this powerful male warrior plant used in smudging ceremonies to cleanse a person or thing of the evil that makes them sick. It is also a disinfectant and inhaled for body aches. The chewed root applied as a poultice over sores, wounds, and burns.

Modern uses: Powdered root may be antifungal and can be applied as a poultice or salve to treat tinea cruris irritations (jock itch) and athlete’s foot. Dry root tincture in warm water or juice appears to soothe sore throats (anecdotal evidence). Plant is little studied or used in any modern scientifically proven context. Traditional uses still practiced.

Notes: Balsam root is widespread in the Bitterroots and other Idaho wilderness areas. In a pinch—should you get lost in these vast mountainous expanses—here is a food that helps you survive. But freeing the root, often deeply and intricately woven into the rock, is an exhausting task.

Polygonaceae (Persicaria bistortoides Pursh.; P. vivaparum L.)

Status of genus is in flux; the plants may also be cited as Polygonum.

Identification: Perennial to 30” with basal leaves and a few smaller leaves produced near lower end of flowering stem. The leaves are oblong-ovate or triangular-ovate in shape and narrow at the base. Petioles are broadly winged. White flowers form from a single dense cluster atop erect stalk, later forming a seed head with brownish achenes (seeds). Blooms from late spring into autumn, producing tall stems ending in single terminal racemes that are club-like spikes.

Habitat: Both species grow from New Mexico to Alaska on wet, open slopes and are abundant in the alpine meadows of Mount Rainier and the Cascades. Visit the nature center garden at Sunrise (the northeast entrance at Mount Raineer) to see this plant and other Northwest medicinals.

Food: Young leaves and shoots are edible raw or cooked. They have a slightly sour taste. Older leaves are tough and stringy. Use leaves in salads and cooked with meat. The starchy root is edible; boil in soups and stews, or soak in water, dry, and grind into flour for biscuits, rolls, and bread. The cooked roots taste like almonds or chestnuts. The seeds are edible and pleasant tasting.

Traditional uses: This vitamin C–rich plant was used to treat or prevent scurvy. The tincture is astringent and used externally on cuts, abrasions, acne, insect stings and bites, inflammations, and infections.

Modern uses: Bistort contains tannins that can help improve diarrhea and mouth and throat irritation by reducing swelling (inflammation) (see McGuffin et al. 1997). Little used today as a medicinal. Traditional uses still employed by montane-dwelling Native Americans and Europeans.

Note: Easily identified and gathered in areas where harvesting is allowed.

Rhamnaceae (Rhamnus alnifolia (L.) Her.; R. purshiana (DC.) Cooper)

Identification: Bush or small tree grows 4’–20’ tall. Has many branches, thornless, densely foliated; when mature the bark is grayish brown with gray-white lenticels. Leaves are thin, hairy on the ribs, fully margined, elliptical to ovate, 2” in length. Greenish-white flowers are numerous and grow on axillary cymes. Flowers are very small with 5 petals. The ripe fruit is red to black purple with 2 or 3 seeds. R. purshiana is taller, to 30’, a Western species, with leaves that have 20–24 veins. White flowers are in clusters.

Habitat: R. purshiana: Foothills of British Columbia, Idaho, Washington, Montana, and Oregon. A lesser known and little used species, R. alnifolia, grows throughout the dunes of Lake Michigan and other Great Lake dune areas.

Food: Not edible.

Traditional uses: Prior to World War II, cascara tablets were available over the counter as a laxative. Native Americans used the bark infusion as a purgative, laxative, and worm-killing tea. An infusion of the twigs and fruit was used as an emetic.

Modern uses: The bark extract is a powerful laxative and Commission E–approved for treating constipation. Bark infusion is a cleansing tonic, but chronic, continuous use may be carcinogenic. Use only under the care of a physician, holistic or otherwise. The laxative response may last 8 hours.

Notes: A naturopathic physician once laced my salmon with cascara extract, a practical joke. Berries from a Rhamnus species in the Midwest once ruined an anniversary dinner. These berries can be mistaken for edible fruit with rueful consequences.

Aralioideae (Oplopanax horridus Sm. Torr.; Gray es. Miq)

Identification: Shrubby, spiny, big-leafed perennial to 10’. Spreading, crooked, and tangled growth covered with thorns. Wood has sweet odor. Dinner plate–size maple-like leaves armed underneath with thorns. Club-like flower head has white flowers grouped in a compact terminal head. Berries shiny, bright red, flattened.

Habitat: Found in coastal mountains and coastline of the northwestern United States and Canada. Seepage sites, stream banks, moist low-lying forested areas, old avalanche tracks. Typically grows at low altitude, but in Canada it may grow to the tree line.

Food: Not often eaten as food, its berries are inedible. According to Moerman (1998), spring buds boiled and eaten by the Oweekeno tribe.

Traditional uses: Related to ginseng, devil’s club’s roots, berries, and especially the greenish inner bark are some of the most important medicinal plants of West Coast Native Americans used in rituals and medicine. Berries rubbed into hair to kill lice or add shine. The inner bark chewed raw as purgative and emetic or taken with hot water for the same purpose. Inner bark infused or decocted to treat stomach and bowel cramps, arthritis, stomach ulcers, and other unspecified illnesses of the digestive system. Root, leaves, and stems added to hot baths and sweat lodges to treat arthritis. The cooked and shredded root bark used as a poultice for many skin conditions. The stem decoction used for reducing fever. Tea from inner bark used for treating diabetes, a common ailment in aboriginal people who now eat a fatty and carbohydrate-rich Western diet. The dried root mixed with tobacco and smoked to treat headache. An infusion of crushed stems used as a blood purifier. Stem ashes and oil used on skin ailments. Traditional use as an abortifacient is disproven.

Modern uses: Scientific consensus reports devil’s club as hypoglycemic. There is a long history of use by Native Americans to treat adult-onset diabetes. Extracts from the inner bark are antibiotic, specifically against the bacterium genus Mycobacterium that causes tuberculosis (see: http://cms.herbalgram.org/herbalgram/issue62/article2697.html). German clinical trials show the plant has anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity. Animal studies show that a methanolic extract of the roots reduces blood pressure and heart rate (Circosta et al. 1994).

Notes: Native Americans burned devil’s club, then mixed the ashes with grease to make a black face paint that was said to give a warrior supernatural power. Bella Coola used the spiny sticks as protective charms. And they scraped bark boiled with grease to make dye. Other Native American hunters sponged a decoction of the plant’s bark over their body to remove human odor—a strategy still in use today.

Pinaceae (Pseudotsuga menziesii Mirbel Franco)

Identification: Medium to large conifer with narrow, pointed crown, slightly drooping branches (deeply furrowed bark on mature trees), and straight trunk. Coastal variety grows to 240’. Single flat needle, pointed but soft ended, about 1” long, are evenly spaced along the twigs. Cones to 4” have winged seeds, 3 pointed bracts extending beyond cone scales look like the legs and rear end of a mouse hiding in the cone; distinctive (see photo).

Habitat: Mountain West and West Coast, from Mexico north to British Columbia; grows best on wet, well-drained slopes.

Food: Shoot tips are used to flavor foods and made into a tea. Pitch chewed as a breath cleanser. Rare Douglas fir sugar accumulates on the ends of branch tips of trees found in sunny exposures on midsummer days—sugar candy looks like whitish frostlike globules.

Traditional uses: This was and is a popular and important sweat lodge plant. Its aromatic needled branches are steamed to treat rheumatism and in cleansing purification rituals. Buds, bark, leaves, new-growth end sprouts, and pitch all used as medicine by Native Americans. A decoction of buds is unproven treatment for venereal diseases. Bark infusion taken to treat bowel and stomach problems. The ashes of burned bark was mixed with water to treat diarrhea. Needle infusion said to relieve paralysis. Leaves made into tea to treat arthritic complaints. Pitch used to seal wounds and chewed like gum to treat sore throat; considered an effective first aid for cuts and abrasions, bites, and stings. Decoction of new-growth twigs, shoots, needles used to treat colds. Ashes of twigs and bark mixed with fat to treat rheumatic arthritis.

Modern uses: Important ritual plant in Native American spiritual rites; many traditional uses still employed.

Notes: Excellent firewood for cooking fish and meat. Also a top-ranked lumber tree used to make clear veneer plywood.

Ephedraceae (Ephedra viridis Coville; E. sinica Stapf)

Identification: There are several Joint-fir species. E. viridis looks like it has lost all its leaves. It is a yellow-green plant, many jointed and twiggy, 1’–4’ tall, with small leaf scales and double-seeded cones in the fall.

Habitat: Various species are found on dry rocky soil, sand, or desertlike areas of the United States: Utah, Arizona, western New Mexico, Colorado, Nevada, California, and Oregon. Numerous plants discovered on route to the top of Fifty Mile Plateau in Utah.

Food: Native Americans infused the roasted seeds. Roasted and ground seeds were also mixed with corn or wheat flour to make fried mush.

Traditional uses: E. viridis (Mormon tea) used in infusion as a tonic and laxative; to treat anemia, colds, ulcers, and backache; to stem diarrhea; and as therapy for the kidneys and bladder. The decoction or infusion considered a cleansing tonic (blood purifier). Dried and powdered stems used externally to treat wounds and sores. The moistened powder applied to burns. Native American women used the plant to stimulate delayed menstrual flow (dysmenorrhea). Seeds roasted before being brewing into tea.

Modern uses: The Chinese powder E. sinica and use it to treat coughs and bronchitis, bronchial asthma, congestion, hay fever, and obesity. It is an appetite suppressant and basal metabolism stimulant. Active alkaloids are ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, which increase body heat, stimulate heart rate, restrict blood vessels, and make breathing easier by expanding bronchial tubes (NIH). American ephedra is available as a tea or in capsules over the counter and but has little or no vasoactive effects.

CAUTION: Ephedra is a precursor in the illicit manufacture of methamphetamine. E. sinica, as a cardiovascular stimulant and central nervous system stimulant, may be dangerous to people with elevated blood pressure, heart disease, and/or tachycardia. The drug is federally regulated and not to be used during pregnancy or by nursing mothers. Numerous drug interactions documented, including death. The import and use of this drug is restricted in several countries. Deaths have been associated with its abuse.

Cupressaceae (Juniperus communis L.)

Identification: Evergreen tree to 50’ or low-lying spreading shrub; often grows in colonies. It has flat needles in whorls of 3, spreading from the branches. Leaves are evergreen, pointy, stiff, somewhat flattened, and light green. Buds covered with scalelike needles. Berries are blue, hard, and when scraped with a fingernail emit a tangy smell and impart a tangy flavor—a somewhat creosote-like taste. Male flowers are catkin-like with numerous stamens in 3 segmented whorls; female flowers are green and oval.

Habitat: Nationwide on mountain slopes, forests, dune lands.

Food: Dried berries cooked with game and fowl. Place berry in a pepper mill or grate into bean soup, lamb stew, wild game, and domestic fowl. For tea, crush 2 berries and add them to water just off the boil. Gin, vodka, schnapps, and aquavit are flavored with juniper berries. Use berries in grilling marinades. Be judicious: Large amounts of the berry may be toxic; use in small amounts like a spice.

Traditional uses: The diluted essential oil applied to the skin to draw out impurities and cleanse deeper skin tissue. It has been used to promote menstruation and to relieve PMS and dysmenorrhea. Traditional practitioners use 1 teaspoon of berries to 1 cup of water, boil for 3 minutes, let steep until cool. A few practitioners add bark and needles to berry tea. The berry considered an antiseptic, a diuretic, a tonic, and a digestive aid.

Modern uses: Mice trials suggest the berry extract in pharmaceutical doses to be anti-inflammatory, at least in the rodents. Juniper oil used successfully as a diuretic and may be useful as adjunct therapy for diabetes (GR). Commission E–approved for treating dyspepsia. The berry is diuretic, and so the extract is diuretic (Odrinil Water Pill) and therefore indicated for treating heart disease, high blood pressure, and dropsy. The berry extract is used in Europe to treat arthritis and gout. Animal studies of the extract in various combinations showed anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activity, but this is unproven in human trials. It decreased glycemic levels in diabetic rats. In human trials, the berry extract combined with nettle and yarrow extracts failed to prevent gingivitis. Juniper oil and wintergreen oil (30 ml of Kneipp-Rheumabad) may be added to bath water to reduce pain.

Notes: Chew on a berry; ripe, soft ones are tastiest. Add 5 berries to duck, goose, lamb, venison, or goat stew and heighten the flavor adventure.

CAUTION: It’s used as an antiseptic for urinary tract problems and gallbladder complaints but contraindicated in the presence of kidney disease; do not use if kidney infection or kidney disease is suspected. Pregnant women should avoid this herb because it may induce uterine contractions. It may increase menstrual bleeding. Do not use the concentrated and caustic essential oil internally without guidance from a licensed holistic health-care practitioner.

Berberidaceae (Mahonia aquifolium (Pursh) Nutt.; M. nervosa Pursh Nutt. var. nervosa)

Identification: Mahonia aquifolium is an evergreen shrub growing to 6’ tall with a gray stem and holly-like, shiny leaves that are pinnate, compound with pointed edges. Small, bright yellow flower; waxy, deep blue berries. Roots and root hairs, when peeled, are bright yellow inside due to the alkaloid berberine. M. nervosa is a smaller forest dweller with rosette of compound leaves in a whorl up to 3’ tall, berries on central spikes.

Habitat: Find M. nervosa along Mount Baker Highway in Washington State. Also in open forests and graveyards. M. aquifolium is found in Washington State and east into Idaho and Montana along roadsides and forest edges.

Food: Natives of the Northwest eat the tart berries of M. aquifolium in late summer. Native Americans smashed the berries and dried them for later use. They may be boiled into jam, but be certain to add honey or sugar because the juice is tart. Carrier Indians of the Northwest simmered the young leaves and ate them. The smaller, creeping M. nervosa is prepared and eaten in the same way, and is preferred, but it is not as abundant. Try berries mixed with other fruit to improve the taste. Berries also are pounded into paste, formed into cakes, and dried for winter food.

Traditional uses: When eaten raw in small amounts, the fruit is slightly emetic. Tart berries of both species are considered a morning-after pick-me-up. These two species of bitter and astringent herbs used to treat liver and gallbladder complaints. The bark infusion used by Native Americans as an eyewash. According to traditional use, the decocted drug from the inner bark (berberine) stimulates the liver and gallbladder, cleansing them, releasing toxins, and increasing the flow of bile. The bark and root decoction reportedly was used externally for treating staphylococcus infections. According to Michael Moore (2003), the drug stimulates thyroid function and is used to treat diarrhea and gastritis. According to Deni Brown (1995), M. aquifolium has been used to treat chronic hepatitis and dry type eczema. Blackfoot used root decoction of M. aquifolium to stem hemorrhaging. Root also used in decoction to treat upset stomach and other stomach problems.

Modern uses: M. aquifolium extractions are available in commercial ointments to treat dry skin, unspecified rashes, and psoriasis. The bitter drug may prove an appetite stimulant, but little research supports this hypothesis. Other unproven uses in homeopathic doses include the treatment of liver and gallbladder problems.

Notes: Simmer the shredded bark and roots of both species in water to make a bright yellow dye.

CAUTION: Do not use during pregnancy.

Betulaceae (Alnus rubra Bong.)

Identification: Member of the birch family that grows to 80’ in height, often much smaller. Bark smooth and gray when young, coarse and whitish gray when mature. A. rubra bark turns red to orange when exposed to moisture. Leaves are bright green, oval, coarsely toothed, and pointed. Male flowers clustered in long hanging catkins; female seed capsule is ovoid cone. Small, slightly winged, flat seed nuts.

Habitat: Species ranges from California to Alaska, and east to Idaho in moist areas.

Food: Members of this genus provide a generous resource of fire-wood in the Northwest for savory barbecue cooking. The bark and wood chips are preferred over mesquite for smoking fish, especially salmon. Scrape the sweet inner bark in the early spring and eat fresh, or combine with flour to make cakes.

Traditional uses: Sweat lodge floors often covered in alder leaf, and switches of alder used for applying water to the body and the hot rocks; alder ashes used as a paste for brushing teeth with a chewing stick. Cones of subspecies A. sinuata also used for medicine, as are other alder species. The smashed pulp of catkins is an oral cathartic (to help move the bowels). Bark mixed with other plants in decoction used as a tonic. Female catkins used in decoction to treat gonorrhea. A poultice of leaves applied to skin wounds and skin infections. In the Okanagan area of central Washington and British Columbia, Native Americans used an infusion of new-end shoots as an appetite stimulant for children. The leaf tea infusion is said to be an itch- and inflammation-relieving wash for insect bites and stings, poison ivy, and poison oak. Upper Tanana informants reported that a decoction of the inner bark reduces fever. An infusion of bark used to wash sores, cuts, and wounds.

Modern uses: This is still an important warrior plant in sweat lodge ceremonies. For more on sweat lodges, see the DVD Native American Medicine and Little Medicine (Meuninick, Clark, and Roman 2007). Black alder, A. glutinosa, is endemic to the Northern Hemisphere and used in Russia as a gargle to relieve sore throat and reduce fever. Research on betulin and lupeol in alder shows it may inhibit tumor growth (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2764818/).

Notes: To smoke meat with alder, soak the wood chips overnight in water, then place the moist chips on coals or charcoal to smoke meat. In 1961 I saw more than one hundred Native Americans smoking fish, moose, and caribou for winter storage along a 10-mile stretch of the Denali Highway in Alaska. Hunting rules at that time required any person shooting a caribou to give some of the meat to the First Peoples, who preserved it for winter food. They filleted fish, stabbed them on a stick, and smoked them over a smoldering alder fire. Ashes of alder mixed with tobacco and smoked. In hardwood-poor areas of western North America, alder burns slower than pine and is a suitable home-heating fuel. Bark is stripped and soaked in water to make an orange to rust-colored dye. Find numerous alder species across North America, often in impenetrable mazes surrounding streambeds—great bear habitat, so be careful.

Cupressaceae (Thuja plicata D. Don.)

Identification: Tall, aromatic evergreen tree. Many branched from the trunk sky-ward. Needles flattened; dark green above, lighter green below. Heavy seed crops produced every 3 years. Fertility reached at about 20 years of age.

Habitat: Windward side of the Cascades, including Vancouver Island and the Olympic Peninsula, and in northern Idaho—moist bottom-land with deep rich soils.

Food: T. plicata’s primary use is and was for making cooking boxes and planks for flavoring and cooking salmon. The cambium (inner bark) could be eaten as a survival food, but there are numerous other safer alternatives (see Meuninck 2013).

Traditional uses: T. plicata is a male warrior plant used by Native Americans in sweeping, smudging with smoke, and steam-bath rituals to clear the body and mind of evil spirits that prevent good health. Northwestern tribes make fine cedar boxes for cooking and storage. Europeans use the wood to line chests and encasements because of the fine fragrance and insect-repulsing chemistry of the wood. A decoction of dried and powdered leaves used as an external analgesic to treat painful joints, sores, wounds, and injuries. Leaf infusion used to treat coughs and colds. The decoction of the bark in water was used to induce menstruation and possibly as an abortifacient. The leaf buds (new-end growth) chewed to treat lung ailments. A decoction of leaves and boughs used to treat arthritis.

Modern uses: Thuja occidentalis is preferred over Thuja plicata as a homeopathic drug to treat rheumatism, poor digestion, depression, and skin conditions. Because of its thujone content, this is a drug used only with professional consultation and supervision.

Notes: This magnificent tree, tall and thick, is a giant of old-growth forests in the Northwest—it makes a durable, decay-resistant wood. Cedar boxes are still used to steam salmon and other foods: Hot rocks are placed on wet plants (often skunk cabbage leaves are wrapped around salmon), and the cedar box is covered with a lid, then the salmon is slow-cooked over steam or pit-cooked surrounded by wet grass under a fire. The trunk of red cedar used to make totem poles and canoes. The inner bark used as basket making material.

Asteraceae (Artemisia tridentata Nutt.)

Identification: Found on arid land, this gray, fragrant shrub grows to 7’ tall. Leaves are wedged shaped, lobed (3 teeth), broad at tip, tapering to the base. Yellow and brownish flowers form spreading, long, narrow clusters—blooms from July to October. Seed is hairy achene.

Habitat: Dry areas of US West and Southwest.

Food: Seeds, raw or dried, are ground into flour and eaten as a survival food. Seeds added to liqueurs for fragrance and flavor.

Traditional uses: A powerful warrior plant used for smudging and sweeping to rid the victim of bad airs and evil spirits. Also used as a tea to treat infections and stomachaches or ease childbirth, or as a wash for sore eyes. Leaves are soaked in water and applied as a poultice over wounds. Limbs used as switches in sweat baths to stimulate circulation. The leaf infusion used to treat sore throats, coughs, colds, and bronchitis. A decoction or infusion used as a wash for sores, cuts, and pimples. The aromatic decoction from steaming the herb inhaled for respiratory ailments and headaches. The decoction taken internally to treat diarrhea and externally as an anti-rheumatic. Decoction is cathartic.

Modern uses: Still very popular and important in Native American Church rituals, including smudging, sweeping, in sweat lodge, and as a disinfectant. For details, see the DVD Native American Medicine and Little Medicine (Meuninick, Clark, and Roman 2007).

Notes: Add this herb to your hot bath, hot tub, or sweat lodge for a fragrant, disinfecting, and relaxing cleansing. It is often the only source of firewood in the desert.

Valerianaceae (Valeriana sitchensis Bong.; Valeriana officinalis L.)

Identification: Perennial to 24”, sometimes higher. Leaves opposite, staggered up the stem, often with several basal leaves. Terminal cluster of white to cream-colored odiferous flowers, petals are feathery. Blooms April to July.

Habitat: Montane plant, typically found on north-facing slopes and plentiful in alpine meadows and along trails in the Olympics, Cascades, North Cascades, Mount Rainier, and Mount Baker, especially along Heliotrope Trail toward the climber’s route.

Food: Edible roots not worth the effort; if you have had the foul-smelling valerian tea, you are nodding your head.

Traditional uses: Stress-reducing, tension-relieving mild sedative for insomniacs. V. sitchensis roots are decocted in water to treat pain, colds, and diarrhea. A poultice of the root used to treat cuts, wounds, bruises, and inflammation.

Modern uses: A few practitioners use V. sitchensis in the traditional way. Aqueous extract of V. officinalis root in a double-blind study had significant effect on poor or irregular sleepers. Valerian combined with hops enhances the sedative effect. The effect of valerian on gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) may reduce blood pressure and help mild depression; this chemical (GABA) is also high in evening primrose seeds and several varieties of tomatoes (GR).

Notes: Take the road to the Sunrise Lodge on the north side of Mount Rainier, walk to the learning center garden, and see this plant and many other medicinal plants of the US West and Northwest—a splendid setting. The plant’s odiferous flowers are not particularly pleasant to many, but I love that stink; it means I’m back in the mountains.

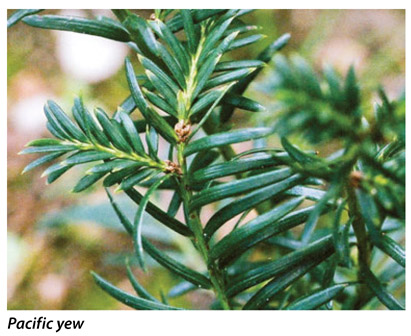

Rhamnaceae (Taxus brevifolia Nutt.)

Identification: T. brevifolia is an evergreen shrub to scanty small tree that grows to 50’. Bark is papery, reddish purple to red brown. Drooping branches. Flat leaves (needles) in opposite rows. Flowers are small cones. Scarlet fruit is berrylike, with fleshy cup around a single seed.

Habitat: From Northern California, Oregon, and Washington through Idaho and Montana, north to British Columbia and Alberta on foothills and moist, shady sites.

Food: According to Daniel Moerman (1998), the Karok and Mendocino ate the ripe red fruit, but the seed and all other parts of the plant are toxic. Unless guided by an expert, avoid eating any part of this plant.

Traditional uses: Native Americans used the wet needles of American yew (T. brevifolia) as a poultice over wounds. Natives considered needles a panacea, a powerful tonic; boiled and used over injuries to alleviate pain. Bark decoctions used to treat stomachache. Native Americans were the first to use this plant to treat cancer.

Modern uses: The toxic drug taxine (paclitaxel) from American yew is used to treat cancer. It prevents cell multiplication and may prove an effective therapy for leukemia and cancer of the cervix, ovaries, and breasts. Clinical trials continue with the drug.

Notes: Research reports that the cancer-fighting chemistry is in both species. It takes nearly 3,000 trees or 9,000 kg of dried inner bark of T. brevifolia to make 1 kg of the drug Taxol. Taxol today is grown in culture from cloned cells in huge bioreactor tanks. Researchers are attempting to produce the drug from pinene from pine trees.

CAUTION: Both species can induce abortion. All parts of the plant are toxic. Unless guided by an expert, avoid eating any part of this plant.