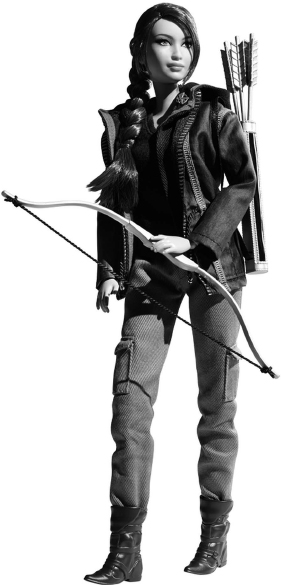

Figure 0.1 ‘The Katniss Barbie’

© Mattel

This book explores the Hunger Games films, produced by Lionsgate between 2012 and 2015. One of the most successful recent youth-directed film franchises, the series consists of: The Hunger Games (Ross 2012, from now on Film 1), The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (Lawrence 2013, Film 2), The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 1 (Lawrence and Ross 2014, Film 3), and The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 2 (Lawrence 2015, Film 4). We will consider a range of approaches to these films across the following chapters, but centrally as a spectacular hybridization of teen, action, and science fiction film which, in their contemporary media environment, we argue could only have a girl hero. Drawing on the films, Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games novels (2008–2010) on which they are based, and the merchandising and fan practices to which they are tied, we situate these films as a crescendo in a long trajectory of representing girl heroes on screen. We will emphasise how these films draw on recent developments in representing gendered youth on film and television, as well as on the distinctly cinematic tone and pacing of Collins’s novels, and link the franchise to a 1990s turn in popular discourse on girlhood often associated with the slogan ‘girl power’. This orientation towards changing images of and discourses on girls is central to how the Hunger Games films function as ‘youth cinema’.

The impact of family and gender on young lives, the limits and significance of agency within the highly institutionalised monitoring of youth, the meaning of immaturity and adolescence, and the association of youth with social continuity and cultural change are all important to these films. Moreover, the Hunger Games narrative requires that these themes are framed as political questions and staged through a story about rebellion against an oppressive state. This book thus does not centrally deal with the Hunger Games films from an aesthetic point of view. Instead, we are interested in taking these films, and the broader franchise they now dominate, as a collective text for discussing how twenty-first century cinema imagines youth, and especially girls. We will particularly focus on the franchise’s hero, Katniss Everdeen: as a spectacle of power, vulnerability, resilience, and transformation; as an icon of virtue, reward and promise; but also, paradoxically, as a figure for the risks attendant on the complex significance of girlhood today. There are, of course, other characters in the Hunger Games story, and other narratives in play than the ones centred on what Katniss can and cannot do, and at what price. But Katniss dominates all elements of the franchise, and that dominance is crucial to understanding its success at this point in the cinematic history of representing youth.

We will also use the Hunger Games films to explore how cinematic stories about youth interact with other aspects of the contemporary media environment. The following chapters not only emphasise the adaptation processes that situate the Hunger Games films in ‘intertextual’ relations to the Collins novels. They also take the Hunger Games as a ‘transmedia’ object, incorporating the fields of promotion, commentary, and critical and fan reception that surround the films. Just as importantly, however, we want to give historical context to the ideas about youth, girlhood, genre and narrative from which the Hunger Games films emerge, and approach the films using textual and theoretical analysis with due attention to the cultural historical moment they represent. The rest of this chapter introduces some key themes and critical tools that weave through our analysis in the following five chapters.

The Collins novel trilogy, The Hunger Games (2008, Book 1), Catching Fire (2009, Book 2) and Mockingjay (2010, Book 3), are the obvious starting point for any discussion of the Hunger Games, and Katniss’s centrality to these is clear. Each novel is narrated from her first-person point of view, Book 1 opening as follows: ‘When I wake up, the other side of the bed is cold.’ (2008: 3) What Katniss perceives and knows largely limits our reading experience, so that we must gradually accumulate what this opening means across the first paragraph: that the cold is noticeable because that other side should be occupied by someone called Prim, from whom ‘I’ seek warmth, but who has bad dreams and might seek comfort elsewhere. We quickly learn that Prim is the narrator’s younger sister, but other details need to be more actively gleaned from Katniss’s narration, including how their shared bed of ‘rough canvas’ signifies the family’s poverty. This narrative style means the reader only gradually comes to doubt whether Katniss knows all we might want to know. She is also what literary critics call an ‘unreliable narrator’: sometimes clearly mistaken and very often unsure of events she cannot see or the motivations of others.1 Yet she is already the moral compass of the story before this becomes clear. The books never invite us to doubt Katniss’s intentions, or whether she should triumph, but gradually important limits on her knowledge and understanding do invite doubts about how completely she will triumph.

The films build on this identification with Katniss, substituting the ‘I’ of Katniss’s narration with the camera’s identification using both her visible responses and her visual perspective. Although they also contain original material allowing the viewer to see and know things Katniss does not, including all the behind-the-scenes elements of ‘The Hunger Games’ as a television text within the text (from now on The Games), this informs how we look through and at Katniss rather than qualifying her centrality. As theorists of the ‘cinematic gaze’ have long argued, film as a rule relies on character identification (far more commonly than first-person narration is used in literary texts), and so the equivalent opening scene of the movie does more than tie us to Katniss’s point of view.

Film 1 opens with a series of prologue screens and establishing shots that build a picture of Katniss’s world: the nation of ‘Panem’ (all that remains of Earth, as far as we know) and, more specifically, Katniss’s home in ‘District 12’. The prologue text establishes the facts of Panem’s post-war treaty, which requires the annual ‘Reaping’ of teenagers (one boy and one girl chosen by lottery from each of twelve districts) for a nationally televised fight to the death. The accompanying shots juxtapose the polished media framing of The Games as television broadcast and the poor rural setting in which we meet our protagonist. The first shot of Katniss (Jennifer Lawrence) is not of her waking but of her comforting Prim (Willow Shields), whose fear at her first Reaping, now she has turned 12, underscores the necessity of resisting this brutal ritual even as it indicates Katniss may be the one to help. The simple styling of the Everdeen sisters and their home contrasts starkly with the ornate styling of the media commentators, just as the nursery song Katniss sings to soothe Prim counters the public callousness of their discussing the political necessity of The Games. Although both Book 1 and Film 1 take time to confirm that Katniss will be the hero such a situation demands, the film conveys far more certainty that the audience should identify with Katniss, using lighting, framing, and editing to keep Katniss’s presence visible in shots and sequences ostensibly focused on other characters. Although she will still soon have enough evident flaws to be an interesting character, the film rapidly identifies with Katniss’s strength and virtue, inviting a different set of audience and fan dynamics. It expands the franchiseable potential of Katniss, and at the same time opens up space for alternative readings focused on characters or stories marginalised by this dominance.

Our focus on the Hunger Games franchise is not a matter of stressing its popularity. In a franchise, the named object is duplicated, elaborated, and repurposed across media, multiplying not only instances but meanings and opportunities for attachment. Discussing the Hunger Games as a franchise stresses the inseparability of the different components it unites, including lateral ties between the four films but also connections across different media. The success of the film adaptations starring Jennifer Lawrence as Katniss, grossing nearly US$1.5 billion in North American theatrical box-office revenue alone, and similarly successful in many other countries,2 fed back into sales of Collins’s novels, the expanding fandom for which provided dedicated repeat film viewers. This is clear from online fansites and in the promotional covers added to re-issues of the books, featuring iconography from the films’ promotions. Somewhat paradoxically, this iconography consists chiefly of symbols generated to sell Katniss as rebel figurehead in propaganda recruiting for a war against the dictatorship of President Coriolanus Snow and the indiscriminate consumption of life in the Capitol (Panem’s capital). Using this iconography to sell myriad Hunger Games objects, from school stationery to makeup lines, has an at least ambivalent meaning for audiences familiar with the story.

The range of ‘Katniss Barbie’ dolls (Figure 0.1) is exemplary. The three available dolls, designed with reference to Katniss’s style in the films, throw into sharp relief the internal story about marketing Katniss and highlight the importance given to Katniss’s various ‘looks’ in the films compared to the books. For example, the Katniss Barbie wears her hair in a single over-the-shoulder braid. This is a signature Katniss style in the films, identified as her authentic at-home look and emphasised as essentially Katniss by various forms of appreciation. When he thinks he will die, her love interest Peeta (Josh Hutcherson) lifts and caresses this braid, and fans in the Capitol are seen to wear their hair this way to identify themselves with Katniss. Just as importantly, fan identification with or cultural commentary on Katniss’s character uses this braid as a succinct way of signifying Katniss that is only minimally supported by the books.

Although such transmedia strategies as those linking the films, the fans, and the Katniss Barbies are by no means confined to youth-centred narratives, they are common in marketing to the young. The concept ‘transmedia’ was first coined by Marsha Kinder (1991) to discuss the relation between advertising and popular media texts’ address to children, stressing how their interest moved fluidly across different fields of consumption. Kinder’s account of transmedia objects positions them as a form of ‘intertextuality’, citing Mikhail Bakhtin’s argument that meaning is always ‘understood against the background of other concrete utterances on the same theme … made up of contradictory opinions, points of view and value judgments’ (1991: 2 quoting Bakhtin). For Kinder, this is principally a way of understanding how audiences operate – how, for example, children might understand the relations between a television programme and advertising juxtaposed with it. Her ideas influenced the more famous work of Henry Jenkins and other writers discussing how audiences participate in the production of meaning. Across Jenkins’s work, this participation has been understood in different ways, but consistently draws on theories insisting that the meaning of popular culture can never be fully determined by authors/producers.3 We also accept this premise, with reference to the shifting relations between: different elements of the Hunger Games franchise, how different citations and tropes become visible to different audiences, and relations between the franchise and its possible – at times, contradictory – interpretations.

Roland Barthes’ theory of intertextuality, which posits that any text is ‘a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture’ (1977: 146), is not only a theory of textuality but also, as John Frow suggests, of how genres work (2014: 45–50). We are also interested in genre as a way of understanding how audiences make meaning of the Hunger Games, and as a way of understanding how the Hunger Games films work as adaptations. Intertextuality describes a field of connections between texts, but genre helps explain how some such connections become dominant guides for interpretation. Any individual textual component can invoke generic associations that transform the meaning of other components (see Altman 1984). These generic attachments may be simultaneously about narrative content, visual style, and audience relations, and the Hunger Games’ guiding generic associations are not only to science fiction/fantasy, romance, action, horror, and teen/youth film genres, but extend to literature, television, video games, and music video. They also draw on genres which do not ostensibly take cinematic form – most importantly, reality television and fanfiction.

The impact of genre on the Hunger Games is not only a matter of identifying groups of texts the films resemble or invoke. The word ‘genre’ slips from that kind of categorization into an opposition between film more broadly and ‘genre film’, a label identifying some kinds of film as more predictably tied to known plots, styles, and modes of address. The Hunger Games films are also ‘genre films’ in this sense, aligned with film genres that more visibly deploy their conventions. This alignment with formulaic popular culture is furthered by their having at their centre a beautiful girl. The association between girls and commodity culture has a long history and the conjunction of generic conventionality, visible fan culture, and prolific merchandising all accentuated this association for the Hunger Games films.

This brings us to two influential critical templates which have underwritten much scholarly and popular discussion of the Hunger Games films (although often only implicitly in the case of popular discourse). Each will return in different forms across the following chapters. The first is a Marxist critical framework which emphasises the association between modern girlhood and capitalist commodity culture, centred on the use of girl images to sell to every marketing demographic. While this book cannot be a theory primer, we will attempt to adequately contextualise our critical tools; and to consider the working of commodity culture, both in Panem and the worlds of its audiences, one must start with ‘commodity fetishism’. This concept was coined by Karl Marx, in 1867, to describe the way commodities are detached from the complex industrial and social relations that produce them, leaving them almost magical objects of ‘worship’ (Marx 1976). In the later work of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, this analytic shifted to focus on media as the primary object of consumption. Their model of media consumption positioned girl fans of popular movies and music as exemplifying the false promises and inauthentic pleasures of mass culture (2002: 97). And in 1967, Guy Debord used commodity fetishism as the basis for his Situationist Society of the Spectacle, arguing that modern media-saturated social relations were detached from sociopolitical structures and also human interest.

We will consider how Debord’s spectacle applies to The Games themselves, and Katniss’s navigation of them, but the Situationists also argued that a girl ideal is crucial to this alienated society. This was phrased superlatively by the collective Tiqqun’s Raw Materials for a Theory of the YoungGirl (1999; see Driscoll 2013), which can be summarised by the following quotations: ‘The YoungGirl is the place where the commodity and the human coexist in an apparently non-contradictory manner’ (17); and ‘The YoungGirl occupies the central kernel of the present system of desires’ (9). Drawing on Debord, Tiqqun identify the problem of commodity fetishism, and capitalism itself (24), with what they see as girls’ own efforts to become commodities. Given that girls have thus long been viewed as the ‘model citizen’ of ‘commodity society’ (Tiqqun 2012: 4), and that both commodity society and model citizens are oppressive forces and enemies in the Hunger Games story, there are necessarily contradictory forces energising the girl image in this franchise.

This overlaps with the second critical template we want to introduce here: the long history of passionate feminist debate about the objectification of girls and women. The Hunger Games films belong to the context of these debates in the second decade of the twenty-first century, when commodification has long been not only something decried by feminists but also a tool used to express feminist ideas. Across the following chapters we will situate the Hunger Games in a feminist history too easily simplified by a ‘waves’ model that pits ‘second wave’ critique of the traps of girlish pleasures against ‘third wave’ demands for access to all pleasures, and a ‘fourth wave’ still tentatively entering this debate through both individual and collective forms of media celebrity. In locating the Hunger Games franchise in this historical situation (a word we choose advisedly), we want to consider both this story’s emphatic critique of the reduction of people to images and the role of image and imagination in possibilities for positive change. The Hunger Games films offer possibilities for identification with multiple versions of Katniss, and the objectified iconic versions cannot be separated from the critical ones even while they remain incompatible. Katniss is not simply a female type, of the kind Virginia Woolf stressed women writers would not produce (1945: 95–100), and she is not reducible to the impossible ideals Betty Friedan saw as tormenting women and distracting girls from more specific life-goals (2001: 126–135). She also cannot be reduced to the erotically dissected object of the cinematic gaze analysed by Laura Mulvey in the 1970s, operating both as the central agent of action and perception on screen and the primary screen object ‘to-be-looked-at’ (1975: 11). Moreover, Katniss is highly conscious of her double role as agent and object, and her story is partly about the different forms that role can take, making the Hunger Games films particularly interesting for feminist analysis.

Fantastic stories in which a girl saves a universe that both is and is not ours are now very numerous. They appear not only in literary and cinematic texts, but on television, and in comics and video games, among other examples. This figure of a singularly special girl clearly appeals to millions, but she is also clearly distinguished from a real world (if only by the spectacular powers she fights). Perhaps she: leads a team safeguarding the universe against evil overbalancing good (Sailor Moon in Naoko Takeuchi’s Sailor Moon franchise, beginning with a 1991–1997 manga); leads defence of the human world against continual attempts to overrun it from dark other-worlds (Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer franchise, beginning with a 1992 film); is pivotal to preventing the rise of an evil wizard-lord (Hermione Granger in the Harry Potter franchise, beginning with J.K. Rowling’s 1997–2007 books); galvanises defence against a tyrannical new government (Tris in the Divergent franchise, beginning with Veronica Roth’s 2011–2013 books); or re-frames the interstellar struggle against tyranny as a girl as much as a boy story (Rey and Jyn in the 2016 and 2017 iterations of the Star Wars franchise, beginning with George Lucas’s 1977 film). Other speculative franchises feature girl screen heroes and many more discrete films or series could be listed, but the increasing visibility is undeniable.

We call the figure that unites these increasingly popular stories since the 1990s, ‘the speculative girl hero’ (Driscoll and Heatwole 2016). If fantasy and science fiction books seem to have led the way in reimagining girl heroes in this period, they were always importantly influenced by new screen images of the girl who fights, or at least fights back, and film and television have in turn taken up and extended this literary shift. Film and television adaptations of older fantastic stories now highlight girls in more heroic roles: reorienting the girl roles for films based on C.S. Lewis’s Narnia (2005–2010); expanding (Arwen) and adding (Morwen) youthful-appearing female roles in the Peter Jackson Tolkien films (2001–2014); or fleshing out the girlhood of Wonder Woman for Patty Jenkins’ 2017 film reboot. It may seem, in the present dominance of super-heroic action films, that there are few equivalent female-centred screen images, with ‘super-heroines’ appearing as off-siders (Batgirl through to the Black Widow) or secondary villains (early Catwoman or Poison Ivy). The minor exceptions, Catwoman (Pitof, 2004) and Elektra (Rob Bowman, 2005) – both injured women fighting back against a world that failed to protect them – are dwarfed by the success of Wonder Woman, a ‘golden age’ superhero (Klock 2002) supported in her world-encompassing virtue by a newly full girlhood story. But the apparent singularity of Wonder Woman requires some qualification.

First, despite several film series about the boy superhero Spider-Man since the 1990s, the other heroes of the Marvel and DC studio blockbuster wave are not boys in the sense that the previous lists feature girls. Youth has been more important to recent super-heroic screen narratives on television, where series like Smallville (WB/CW, 2001–2011) and The Flash (CBS, 2014–ongoing) sit alongside girl-centred stories like Supergirl (CBS/CW, 2015–ongoing) and Crazyhead (E4, 2016–ongoing), as well as alongside more ensemble narratives, like Misfits (E4 2009–2013) and DC’s Legends of Tomorrow (CW, 2016–ongoing). Speculative television more generally tends to feature adolescent and younger adult characters, as in Supernatural (WB/CW 2005–ongoing), Being Human (BBC3 2008–2013), The Vampire Diaries (CW 2009–2017), and Teen-Wolf (MTV 2011–ongoing); although, as with Buffy (WB/UPN 1997–2003), longer series eventually qualify their youth-centred narratives. This is partly because television is more easily consumed in domestic spaces and often without special access requirements. Television and books have thus together furthered demand for cinematic girl heroes like Katniss.

The broad characteristics of this speculative girl hero should also be sketched here. She is fundamentally brave and honest, with courage extending both to intrepid physical action, even when she fights reluctantly, and to critique of the way the world works around her, although she is often less insightful about herself. She thus opposes the traditional representation of girls as prizes rather than agents in myths, legends, and folktales. She also always represents the challenges posed by expected gender roles, as well as the comforts and pleasures they can offer. She often positions these contradictions as unresolvably complex, with the sacrifice of some pleasures or forms of self-validation required to choose others. Our interest in this girl hero arose from the way that, despite her strengths, this girl thus seems open to feminist critique because her action and achievement are often accompanied by images of femininity.

Of course, girl heroism is not the only aspect of the Hunger Games films worth discussing in a book about their representation of youth. Katniss herself does not exhaust the significance of youth to imagining a new future for Panem, and an overview of the roles played by age in the franchise will be helpful here. There are, broadly, four types of individuated characters, and the symbolic importance of youth crucially defines them all. The first (small) group consists of Katniss’s sexualised love interests: Peeta and Gale (Liam Hemsworth). These strongly differentiated characters do more than flesh out Katniss’s character by way of her options, drawing on highly recognisable teen romance conventions. They also stand for social difference in District 12, and different sociopolitical choices, and their youth means Katniss must try and ascertain not only who they are but who they are becoming in terrible circumstances. Like all youthful characters in this story, their suffering seems more tragically serious because of other experiences foreclosed on, and in this respect, not only Peeta but also Gale is a tribute to The Games, indicating its destructive impact.

The second (largest) group of characters consists of the Hunger Games competitors. There are twenty-two tributes, other than Peeta and Katniss, in the 74th Hunger Games (Film/Book 1) – all adolescents aged between 12 and 18 selected as ideal for television spectacle as well as for political suppression because they are young. The most prominent are Rue (Amandla Stenberg) – the youngest, whom Katniss takes as a sister-substitute and tries to save, then mourns – and Cato (Alexander Ludwig) – the final antagonist who represents everything villainous that childhood training for The Games can produce. There are not strictly any ‘tributes’ in Book/Film 2 because the 75th Games are a special ‘Quarter Quell’, with past Games ‘victors’ reaped again. There are once again twenty-two competitors, beyond Peeta and Katniss, this time of various ages. The five significant characters include the elderly Mags (Lynne Cohen), and two middle-aged victors, Beetee (Jeffrey Wright) and Wiress (Amanda Plummer), but the two most important are young adults – Finnick Odair (Sam Claflin) and Johanna Mason (Jena Malone). This range finally proves Katniss’s authority to represent Panem, rather than merely the symbolic power of sacrificing youth. Perhaps in part because they know they are at risk as part of a plan to end Katniss’s popular influence, and certainly because many are conspirators in a plot to save her and spark a revolution, all the competitors focus their attention on Katniss – either as the one they must defeat or the one they must save. Of those who survive, only Beetee is not youthful, and in Book 3/Films 3–4 he is quickly incorporated into the social structure of District 13 while Johanna and Finnick remain important indices of the damage done by The Games, even to winners.

The third group – the first we meet as they help convey what kind of girl Katniss is – are her family and neighbours, the ‘people’ of District 12. In the films, neither the mayor nor ‘peacekeepers’ are characterised, so these residents represent the downtrodden ordinary life of Panem. Only three are important, with recurring characters from the novels like Gale’s family, Greasy Sae from the black market, or Madge the mayor’s daughter, reduced or merged to throw these few into sharper relief. Haymitch Abernathy (Woody Harrelson) needs separate consideration later, as his mobility between District 12 and the rest of Panem sets him apart, leaving only Katniss’s sister and mother. Her mother (Paula Malcomson) seems largely helpless in Film 1, and does not even have a given name. Although given a minor healing role in the later films, she mainly functions to show why Katniss has developed superior self-reliance. This is dramatised further by Prim. As the only other individuated adolescent in District 12, and the first whose name we see called for Reaping, only for Katniss to volunteer in her place, Prim first stands for vulnerability (Figure 0.2). She demonstrates Katniss’s capacity to nurture and empathise when her other attitudes and actions might seem harsh. In the later films, Prim becomes more independent, but this only heightens the tragic impact on Katniss when her sister is killed during the war. As heralded by Rue’s fate, Prim only just seems to begin growing into whatever would have been herself when Panem kills her.

The final group unites Katniss’s adult supporters and enemies who together form the social field that Katniss must struggle to defeat, save, and renew. They are principally the results of what is wrong with Panem. As the previous rebellion ended with The Games treaty seventy-four years before Book/Film 1, even President Snow (Donald Sutherland) and the rebel president Alma Coin (Julianne Moore) grew up under its influence – Snow being 75 and Coin around 50 when first introduced. Snow is evil the way The Games are cruel, and it is thus fitting that his whole life is coextensive with them. He also represents Panem’s failure to nurture anything of value, symbolised by his undying/un-aging white roses – an image of artifice unmarked by experience. Most characters, however, like Plutarch Heavensbee (Phillip Seymour Hoffman) and Coin, represent more complex versions of the harm done by self-interested exploitation of others. The audience is invited to share Katniss’s uncertainty about their motivations and likely actions, and to reconsider them as Katniss does. The most fully characterised is Haymitch, who is also the hardest to place in our taxonomy. He is a surviving victor-tribute, although never in the arena during the films; he is one of the District 12 constituents Katniss represents; and he works variously as Katniss’s antagonist and supporter, often positioned as having a special understanding of her weaknesses and potential. The novels specify that Haymitch won the 50-year Quarter Quell, and is thus somewhere between 37 and 53, but he continues to represent the sacrifice of youth imposed by The Games. Having spent twenty-four years training the children of his district for death, Haymitch is routinely drunk, and his eventual role in Katniss’s survival and the rebel victory never changes this. Haymitch is never quite redeemed, but also never quite at fault. In many respects he is Snow’s opposite – a critical guide who knows and represents the failings of Panem but cannot change them directly.

Although Katniss survives the eventual showdown with both presidents, and they do not, it is never entirely clear that she is victorious, or what she has won. In this respect, Katniss’s story resembles many youth film dramas in which the achievement of a more mature understanding of the world is a very ambivalent victory. Katniss’s increasing maturity is tracked by her changing relations to others, including her love interests, as the conventions of youth cinema would expect, but also to the world of adults defined by their occupations whom Katniss must either oppose or rely on for survival and, later, achievement of her changing goals. Most effective emotional and practical support is offered by the stylist Cinna (Lenny Kravitz); and the irony of a stylist being the only entirely trustworthy and reliable adult is an important one. Although the overall narrative is highly ambivalent about their work, professionals in image production are among Katniss’s most reliable supporters. These include the public relations representative Effie Trinket (Elizabeth Banks), and Katniss’s makeup team in the first two films and her film production crew in the final two films. That the dramatic conflict propelling the overall narrative is centrally about image production becomes clearer when we notice that her most important adult antagonists are also focused on image control. In addition to the two presidents, there are the two Gamemakers, Seneca Crane (Wes Bentley) for the 74th Games and Heavensbee for the 75th, and the television host Caesar Flickerman (Stanley Tucci). Compared to these image-workers, there is far less agency among the peacekeepers and soldiers who are occasionally distinguished by particular events. Though their responses may range from oblivious brutality to self-sacrificing sympathy, they generally follow the orders of politicians. Politics and the media are represented as violent forms of cooperating image manipulation that the military merely reinforces. They constitute concrete regimes of oppression against which better stories/images are a necessary, and perhaps the most effective, response.

The importance of youth to fantasy and science fiction is continuous with the importance of youth to social analysis, which takes youth as an index of the present and sign of the coming future. To conclude our introduction, we turn to some dominant ideas about the social context in which the speculative girl hero emerged. Just as youth cinema is not exclusively Anglophone (Shary and Seibel 2007; Driscoll 2011: 149–162), the social and cultural theories that surround this girl hero’s renovation since the 1990s have an international frame of reference. They are, however, principally produced in, and principally refer to, societies dominated by transnational commodity capitalism and its tensions with forms of national state welfare. This section introduces a series of concepts that seek to understand this context, and which help us understand the world imagined by the Hunger Games. We will briefly introduce the Foucauldian concepts of disciplinary power, governmentality, and neoliberalism, then discuss postfeminism, and finally turn to the concept of risk society.

Collins has repeatedly said that her Hunger Games novels are ‘basically an updated version of the Roman gladiator games’, and that she was inspired to write it while

channel surfing between reality TV programs and actual war coverage. On one channel, there’s a group of young people competing for I don’t even know; and on the next, there’s a group of young people fighting in an actual war. I was really tired, and the lines between these stories started to blur in a very unsettling way.

(Collins, quoted in Margolis 2008)

In drawing on this contemporary media collage to tell her story about bread and circuses (Panem being named after the Latin word for bread and The Games operating as its circus), Collins produces a sharp historical contradiction that adds frisson to the story. And the figure of young people competing for media supremacy offers a powerful interpretation of the contemporary world.

Across a number of publications, Michel Foucault argues that modern social power shifted away from the direct display of a sovereign’s right to kill. In ‘Society Must Be Defended’, Foucault states:

I wouldn’t say exactly sovereignty’s old right – to take life or let live – was replaced, but it came to be complemented by a new right which does not erase the old right but which does penetrate it, permeate it. This is the right, or rather precisely the opposite right. It is the power to ‘make’ live and ‘let’ die.

(1997: 241)

Foucault called these new technologies for assessing and managing populations ‘biopower’. The operation of state power was supplemented by the management of people, which he also refers to as ‘disciplinary’ power. While the iconic Foucauldian account of disciplinary power is the self-monitoring of prisoners who are institutionally compelled to fear they might be being watched at any time (1977: 202–203), in The History of Sexuality he clarifies that this shift to disciplinary power encompasses new modes of education and parenting, as well as new ideas about the sexed self (1978: 104). Given these historical shifts, the capital punishment aspect of The Games that makes Panem seem so archaic is made ‘almost believable’ (Todorov 2000) for the twenty-first century by media technologies that tie it to contemporary anxieties. Panem works through a mesh of sovereign and disciplinary power – through schools as well as gladiatorial combat, through the state-media complex and biopower as well as through floggings, torture, and war.

These modern modes of government centre on the birth of ‘liberalism’, the philosophy of democratic government grounded in a social contract between free-acting individuals and the state embodied in civil institutions. In his analysis of liberalism, Foucault also coined the term ‘governmentality’ to discuss how states developed mechanisms for ‘the conduct of conduct’ (Gordon 1991: 2) that require, encourage, and reward the self-government of individuals through laterally dispersed operations of governance. These lead to his accounts of ‘neoliberalism’, a now very widely used term – in popular as well as academic contexts – to describe the integration of these governmental operations with free market economics. The concept of neoliberalism has been progressively detached from economic theory and is now used to describe Western society in general. As Wendy Brown exemplarily puts this argument, in ‘neoliberal society’ ‘everything is “economized” and … human beings become market actors and nothing but, every field of activity is seen as a market’ (Brown 2015).

The concept of ‘postfeminism’ now operates as an account of what neoliberalism means for, and does with, the achievements of feminism (although it too once meant something far more specific). In its popularisation since the 1990s, it has become closely linked to images of successful girlhood – what is sometimes called ‘girl power’ feminism and which Anita Harris discusses as the rise of iconic ‘can-do girls’ (2004a). Can-do girls, appearing in a variety of popular media sold predominantly to girls and women, are more imagery than reality – they are a girl spectacle in Debord’s sense. As Harris argues,

What is not highlighted, but is fundamentally important here, is that material resources and cultural capital of the already privileged are required to set a young woman on the can do trajectory. Instead, the good or bad families, neighbourhoods, and attitudes are held to account.

(Harris 2004a: 35)

The contemporary girl-powered girl faces an equally contemporary potential for failure, making girlhood a subjectivity in need of special concern and protection. It matters in this sense that speculative girl heroes belong to worlds in which many recognisable contemporary obstacles to girlhood success have been removed. For example, the importance of class is often demobilised (the Hunger Games is interestingly an exception), often by loosely feudal social orders in the case of fantasy or by technocracy in the case of science fiction; and while central characters are often unmarked by race (implicitly white), the possibilities of an imaginary world can obscure this for both creators and audiences.

While invocations of girl power now seem intrinsic to post-1990s preteen and adolescent girl culture, this emerged simultaneously from girls’ activism – the slogan itself belonging to post-punk musicians and zine-makers in the United States (US) in the early 1990s – and from a media-driven moral panic with the girl at its centre. The ‘riot grrrl’ origins of girl power have over time been dwarfed by less confrontational versions of popular music and publishing for girls, most famously the Spice Girls in the United Kingdom (UK) later that decade. But girl power also took its force from campaigns stressing girls’ capacities among parents and institutions, inspiring new popular texts and lobbying for new girl-centred policies, although these clearly supported the interests and presumed the opportunities of some girls more than others. These campaigns can be summarised using Mary Pipher’s influential popular psychology text, Reviving Ophelia, which famously referred to girls entering adolescence in the era after ‘second wave’ feminism as ‘saplings in a hurricane’ (1994: 22). This hurricane was driven both by the resilience of traditional images of ideal girlhood and by the choices made available to them by feminist success in the areas of non-reproductive sex, careers for women, and life narratives independent of marriage and family. The burden and costs of fulfilling the hope created by those successes generated what later theorists refer to as a self-destructive ‘melancholia’ (McRobbie 2009: 111–119) in response to a ‘postfeminist sensibility’ pervading media culture (Gill 2007).

In the realm of speculative fiction, the risks heroines face are often concrete and immediate – death, injury, social or even world-destruction – but less tangible risks associated with postfeminist girlhood are also evident. Beyond staying alive and saving others, Katniss and other contemporary ‘young adult’ (YA) heroines remain anxious about how they should appear and relate to others in often very traditional ways. Hegemonic expectations for gender performance are important in many of these narratives, but in the Hunger Games, resistance to them could mean death. Katniss’s survival is linked to her ability to represent a desirable and desiring subjectivity. She is called upon to be both special and a manageable citizen in some fundamentally girl-oriented ways as well as to fight savagely for her own survival while proving her individual worth by generosity towards others. In particular, she must learn to embody a femininity articulated through fashionable style that she finds baffling and pointless in ways that echo much of McRobbie’s argument about a ‘postfeminist masquerade’ that encourages girls’ complicity in hegemonic gender codes (2009: 59–72). Performance of this masquerade is required even while its superficiality is stressed, and as the typical goals of a bildungsroman must be subverted in favour of survival.4

What ‘can-do’ girls can do is achieve successful womanhood, and because of the impossible vagueness this involves and the immanent risk of failure, this goal is framed as a process of risk management. Thus, the postfeminist story of girl empowerment aligns with neoliberalism in that successful life outcomes are determined by detecting and avoiding risks and managing opportunities by making the right personal choices. Such individualisation downplays structural and cultural inequities, including in presuming that gender itself is no longer an obstacle given past feminist successes. Evaluating Katniss’s choices by any of these standards is, however, largely rendered meaningless by the fact that youth in Panem do not face similar struggles to produce a viable adulthood, and our presumptions about girlhood risks are made strange when thrust upon Katniss. Except for those born in the Capitol, and we know very little of youth there, who one will be is largely a foregone conclusion. When chosen as tribute Katniss is hurled from a world relatively unconcerned about youthful identities to one where construction of such an identity is necessary for survival. Her identity is suddenly mediated by the values of the Capitol, where ‘sponsors’ can decide whether she lives or dies and management of one’s self-image is a principle concern. Only on television, that is, does Katniss become a hyperbolic parable of contemporary girlhood.

The promotion slogan for The Games is ‘May the odds be ever in your favor’, but we first hear this phrase used sarcastically in a conversation between Katniss and Gale, which makes clear how well the people of the districts know the odds are stacked against them all. There is always a good chance of being chosen in the Reaping, especially for the more disadvantaged who will trade extra inclusions of their name in the lottery for food tokens called ‘tesserae’. There is little chance of winning those Games, especially for those already undernourished. And there is no chance of living a life not dominated by continually weighing the risk of starvation against the fear of being apprehended for violation of trade, labour, hunting, and myriad other rules and the risk of the tesserae. This brings us to the concept of ‘risk society’, another interpretation of neoliberalism which at first glance is also tied to a society very different from Panem. Risk society is also discussed as ‘reflexive modernity’ in order to argue that it is organised around the ‘hazards and insecurities’ produced by modernity itself (Beck 1992: 21), from environmental degradation to systemic poverty. Here it matters that Panem is not just a fictional world, but an imagination of the US in the future, after an environmental disaster that flooded the land, reshaping society. The risks and insecurities underpinning life in Panem are meant to be both like and unlike our own, including in situating youth as the pre-eminent image of our future-oriented social anxieties at both personal and world-shaping levels.

In a 2008 review of Book 1, novelist Stephen King declared that ‘Reading The Hunger Games is as addictive (and as violently simple) as playing one of those shoot-it-if-it-moves videogames in the lobby of the local eightplex; you know it’s not real, but you keep plugging in quarters’ (King 2008). He felt Katniss was too conveniently spared actual harm, need, or horror, but also that the books hinged on whether or not you cared about what happened to her, and he did. However, once Film 1 had become a blockbuster hit, in 2013, King revised his opinion, saying he ‘didn’t feel an urge to go on’ with the story. While reserving his more detailed disdain for the Twilight and Fifty Shades franchises, King now grouped them all as obviously stories for girls because nothing was really at risk in them (King, quoted in Stedman 2013). King’s own stories specialise in encounters between innocence and monstrosity, but in this case he is looking for the wrong kinds of harm and risk. There are no killer clowns hiding in sewers in the Hunger Games, but there is an oppressive web of institutional and individual limits that make youthful engagement with the future feel impossible. It is Katniss’s confrontation with, and transformation of, this system that makes her not simply heroic, but a girl hero.