Indonesia has seemingly been plagued by instability for much of its history. Its geographic position along a major trade route made it attractive for colonization and violent exploitation. World War II resulted in the displacement of Dutch colonial rule by Japanese occupation, followed by a postwar independence struggle against the Dutch as they attempted to reassert control. Subsequent disputes arose as to what the nature of the newly independent state should be: Islamic or secular, unitary or republic, one or many states. Since that time, instability has been rather pervasive, complicating attempts to study it. The Indonesian government has been persistently challenged with secessionist movements, ethnic and religious disputes, communal clashes, and coup attempts. Governmental response has typically been repressive. It is rare that the government has the luxury of addressing one incident of violence at a time. This is further complicated by the geography of the country, which results in a dispersal of violence across the archipelago’s many islands.

This chapter examines violence in Indonesia and the factors that influence its dynamics. The analysis examines diverse cases of violence, including the ideological conflict that occurred nationwide against the Darul Islam Movement (1953–1961), Permestas (1958–1961), and the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (Permerintah Revolusioner Republik Indonesia, or PRRI) (1958–1961), and the identity-based conflicts in the regions of the South Moluccas (1950), West Papua (1965–1984), East Timor (1975–1998), and Aceh (1989–2005).

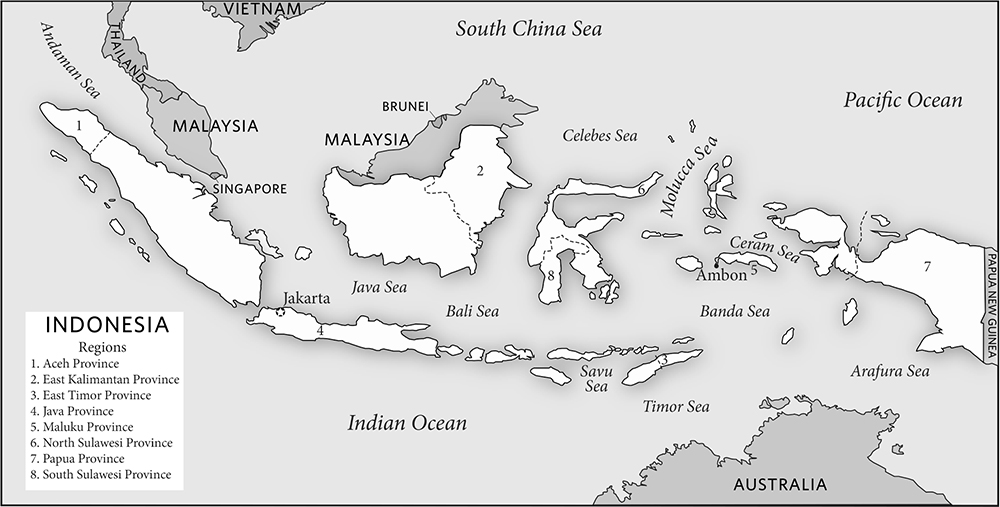

Indonesia is an archipelago of 17,508 islands, fewer than half of which are inhabited. The combined size of its territories is about three times the size of the state of Texas. The largest of the islands are Java, Sumatra, Borneo, New Guinea, and Sulawesi. The terrain that would be encountered by combatants varies by island and specific location on each island. Most of the islands that constitute the country are largely tropical lowland regions, with some of the larger islands also having mountainous highlands. The archipelago is located along the Ring of Fire, resulting in several of the islands being volcanic and relatively frequent earthquakes. Each island within the chain has its own sociopolitical makeup, cultural groupings, and economic characteristics, all of which contribute to the country’s diversity. One author has commented that “many of [Indonesia’s] problems still looked insurmountable [at the end of 2006], mostly because of the nearly impossible archipelagic geography and its implications for state organization” (Kingsbury 2007, 161). Thus, even in modern times, the country’s island makeup creates challenges for governance. One of the most important implications of the geographic dispersal of the country is that the government has been challenged, at times, by multiple foes at the same time but on different islands. These opponents differ in character, grievances, strategies, tactics, and demands.

The country’s islands are situated in the Indian and Pacific Oceans and are near the contentious South China Sea. Among the countries in relative proximity are Australia, Papua New Guinea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar. Given the neighborhood in which it is situated, it is not surprising that Indonesia was impacted by the Vietnam War and the growing importance of communism in the region. Furthermore the many different conflicts experienced within countries of the region have impacted Indonesian government and society.

Each island has its own religious, ethnic, and cultural identity. The country has been faced with numerous secessionist movements; some violent, others bloodless. In a few cases, these have been long-term activities that started at, or even before, independence. Examples of these would be the secessionist movements in Aceh and East Timor. A key division in Indonesian society, regardless of the specific island, is between the Javanese and those from other areas of the country who share the perception that the Javanese are unfairly advantaged in the system. The Javanese comprise nearly half of the country’s population and are seen as being unfairly benefited in the system. They control most of the country’s major government seats and corporate interests (Weatherbee 2002).

This is further complicated by the uneven distribution of natural resources in the country. The areas richest in natural resources are Aceh, Papua, Riau, and East Kalimantan (Tadjoeddin and Chowdhury 2009, 39). People in many regions were unhappy with the “New Order” policy of the Suharto government (1966–1998) that monopolized the use of resources in many regions of Indonesia. “People outside of the Island of Java . . . were particularly frustrated with the centralistic government. They felt that they had never enjoyed the benefits of development and probably never would because the people in Jakarta were ‘taking and eating most of the fruit’” (Ananta 2006, 3).

Natural gas and oil deposits have been exploited and controlled by the central government, with the associated revenues largely remaining in Java. Each of the resource-rich regions has attempted to secede from Indonesia in what Tadjoeddin and Chowdhury (2009) refer to as an aspiration to inequality, or a desire for the resource-rich areas to retain their economic superiority. The anger over the loss of control of their local wealth has been exacerbated, in most cases, by the control of the resources by nonlocal representatives. Typically, Javanese citizens have been sent to develop the natural resources of other areas and to manage and work in the industries that arise. This has resulted in the presence of very wealthy, well-educated “foreigners” or “others” in the resource-rich areas. Furthermore, under the Suharto transmigration policies, many Javanese and other groups moved to these regions, with the perception that the natural resource wealth would mean better jobs and higher incomes. Some of the resource-rich regions have compromised with government on their secessionist demands in exchange for the return of a greater proportion of the revenues generated by their natural resources. Aceh has achieved the most significant benefit from its struggle, with a peace agreement promising the return of up to 70 percent of the wealth generated through the sale of the region’s resources (Weatherbee 2002).

Religion has also played a role in instability. Indonesia has the world’s largest Muslim population, with over 86 percent of its citizens practicing Islam. Because of this preponderance, one of the persistent debates in the country is the role that Islam should play in governance. Through its recent history, the national government has varied between efforts to restrain the role of Islam and times when it sought to promote its interests. As the country has moved toward a more federal system in the post-Suharto era, one of the major factors in the quest for local autonomy and in the ceasefire agreements has been the role of Islam in local governance. Christian/Muslim violence is not uncommon; however, religion is not the predominant source of conflict in the country.

Violence in Indonesia is so pervasive as to have caused some to hypothesize that it is inherent in its culture (for a discussion see Varshney 2008; Coppel 2006; Collins 2002). There have even been arguments that Indonesian culture and human rights are irreconcilable (Asplund 2009). Violence permeates the country in various ways, including communal unrest, government repression, coup attempts, religious conflict, harsh police tactics, and deadly vigilantism. While it may be an exaggeration to refer to Indonesia as having a “culture of violence,” it must be admitted that the people of the country tend to be accepting of violence as a means for addressing problems. Some say this can be traced back to the colonial era, when corporal punishment was used by the Dutch to ensure compliance (Colombijn 2002, 51).

The country declared its independence from the Netherlands on August 17, 1945, but it was December 27, 1949, before it was officially recognized. The intervening years were strife ridden, as Indonesian groups fought the Dutch presence on the island, and each other in many cases. Indonesia’s postcolonial experience was tumultuous. Even during the struggle for independence, there were some in Indonesia, including many Dutch members of the military, who felt that the country should remain part of the Dutch sphere of influence. In contrast, the independence movement united others against the common Dutch enemy. Once the country was free, the differences among groups came to the forefront, sometimes resulting in independence movements. These often resulted in violence and the need for the newly formed Indonesian government to fight battles on multiple fronts and on several different islands at the same time, spreading resources thin and diluting its capacity.

Many of Indonesia’s conflicts come from the immediate post-independence period. When the Dutch, under pressure from the international system, agreed to relinquish Indonesia, an agreement called the Round Table Conference of 1949 was signed. This specified that Indonesia would be a federal republic, and that each territory had the right to join the republic or not. However, shortly after independence was granted, on August 17, 1950, Sukarno declared Indonesia a unitary state (Yaeger 2008, 216; Horikoshi 1975, 72). The state’s identity-based conflicts arose from regions’ desires for independence. The country’s one ideology-based conflict emerged after independence, as debates about the role that religion would play in the new government stimulated conflict. There were some in the country who had thought the new state would be Islamic and were disappointed at the new government’s secular nature (Arifianto 2009, 73–75).

The Dutch had also initiated policies designed to alleviate poverty in Java and Madura. Javanese were essentially paid to move to one of the less populated islands. The migrants were sometimes compensated with land rights or used the funds given to them by government to buy property (Tajima 2008, 458–459). These policies were resurrected by the Suharto administration’s transmigrasi policies, which were intended to alleviate overcrowding and poverty. By one estimate, by 1990 as many as four million were resettled “to Kalimanta, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Maluku and West Papua” (Djuli and Jereski 2002, 43). The areas of the country that were attractive to the Javanese varied depending on what territories offered the best opportunities for the migrants; this could mean available land, employment in resource extraction or other sectors, or a perception that the area was safe. Families of migrants who have lived in the host territories for generations are frequently still treated as outsiders by those indigenous to the islands.

Lethal violence was also cultivated by the government at various times (including the independence movement and the purge of Communists in the mid-1960s) when it suited its purposes. In many cases where communal violence has taken place seemingly without a government role, it has later been found out that government provided support to one side or the other. The country is remarkably diverse, with cleavages dividing people in many ways: religion, ethnicity, region of the country, language, socioeconomic status, and urban versus rural dwellers. People are also divided along the lines of major political decisions facing the country, including the desirability of independence (national movement or for any region), the value of democratization, the role that the military should play, desirability of secular government, distribution of national wealth, the value of decentralization, and natives of a region versus those who have moved there from elsewhere in Indonesia. At one time or another, in various regions across the country, each of these issues has resulted in bloodshed. This incredible heterogeneity led Wirajuda to observe that “Indonesia is a multiethnic state-nation, which means that the state plays an instrumental role in creating the nation—rather than the other way around” (Wirajuda 2002, 17).

An important factor in the civil-military relations in the country is the violence that occurred in 1965–1966. After an attempted coup was blamed on Communist actors, the Indonesian government and citizens went on a large-scale purge of Communists, resulting in the massacre of an estimated five hundred thousand (Collins 2002; Bertrand 2008). Discussing the events that occurred at that time remains largely taboo, even in the media (Collins 2002). The lasting impact is a general distrust of government and the military due to their role in the carnage. An additional challenge experienced regarding the military was the doctrine of dwifungsi, which established a dual function for the country’s military, adding domestic political stability and economic development to the more traditional role of the military as a protector from external aggression. This policy stood until 2000, when parliament dictated that the police be separated from the military (Tajima 2008).

Religious disputes have also been part of Indonesia’s identity-based conflict history. Where Christians have tended to believe Muslims are attempting to shift Indonesia to an Islamic state, Muslims have accused Christians of campaigning to convert Indonesians to their faith (Arifianto 2009, 74). Because of the preponderance of Muslims in the country, Christians have been accepting of authoritarian administrations that have tended to be inclusive of all religions. They fear the treatment they would receive under a democratic regime or, perhaps worse, in an Islamic state. Muslims, on the other hand, witnessed the mass conversion of Muslims to Christianity after the Communist purges of the late 1960s after which Muslims were accused of having been aligned with the Communists (Arifianto 2009, 81). All of these issues, in addition to the shifting preferences the Dutch and subsequent Indonesian administrations showed toward the two faiths, combined to create deep distrust and animosity. A series of religious-based conflicts erupted at the end of the Suharto regime in 1998, which resulted in nearly ten thousand deaths (Tadjoeddin and Chowdhury 2009, 38). It should be noted that the degree to which these conflicts were truly religiously motivated is debatable. Because of the many cleavages among the combatants, some may be more accurately identified as ethnic, but that may be a difficult determination to make.

The long history of violence in the country, both communal and between groups and government, has left the people of Indonesia untrusting and feeling insecure. Distrust between societal groupings is the norm, with each fearing that the others are getting more from the system or are colluding with perceived enemies. Interpersonal violence ranges from episodic to sustained campaigns. Low-level fighting between individuals is so prevalent that scholars and citizens differentiate “everyday” or “routine” violence in the Indonesian context as that which is not tied to a major, sustained violent outburst (Tadjoeddin and Chowdhury 2009, 43–44). Government participation in massacres, extrajudicial killings and other forms of violence, and human rights violations have led to public distrust of both its intentions toward them and its ability to resolve local conflicts.

Vigilantism is prevalent in the country, and the penalty for thievery is often death at the hands of villagers. This was reportedly tied back to the colonial code of Indonesia, which permitted the killing of thieves (Hefner 2003, 1005). Historical government practices may have reinforced the public tendency toward fatal vigilante justice. The most remarkable period of time in this regard was 1982–1985, when government-sponsored forces killed between five and ten thousand petty criminals and left their bodies on public display to discourage crime and foster order (Colombijn 2002, 52). This was under an “Elimination of Crime” policy program, which is sometimes referred to as Petrus, a contraction derived from indigenous words for “mysterious” and “shootings” (Pemberton 1999, 196). The public practice continues today and, in fact, has increased in the post-Suharto era, as some citizens perceive government as being unwilling or unable to address problems. Through time, bands of premans (thugs) have roamed areas of the country providing security at a cost to villagers. The premans then give over a portion of their earnings to local government officials. Post-Suharto, there has been an increase in anti-preman violence (Giblin 2007, 521).

A related phenomenon occurred in Indonesia in 1998 when the country moved from the New Order of the Suharto regime to the reformasi regime of President Habibie. Part of this, under international pressure, was an emphasis on increasing human rights protections in the country. While it would seem that this would result in improved security for the people, in some cases it led to increasing human rights violations among the citizenry. In at least some regions and among some people, the perception developed that HAM (Hak Asasi Manusia, a translation of “human rights”) interfered with the ability of government to do its job (Herriman 2006, 378). For example: “When a Muslim man who would later form an ad hoc militia asked an army officer why the military did not intervene, he replied that with only ten ill-equipped soldiers, they lacked the capacity to repel a mob of hundreds of Christians and that the military ‘could not kill the [fighters] because of human rights’” (Tajima 2008, 466). Police and military personnel could no longer, for instance, kill suspected sorcerers, so it was now up to the citizenry to punish those accused of wrongdoings (see, for example, Herriman 2006). In other cases, local militias formed to address perceived problems because human rights placed restraints on the extent to which the military and police forces could act (Tajima 2008).

An additional observation about the nature of the groups in Indonesia is that the cleavages among the people have been reinforcing, rather than cross-cutting. In Aceh, for instance, traditional Acehnese have tended to be agrarian, poor, and uneducated and to support secessionist movements. In contrast, the Javanese who moved to the area under transmigrasi are more likely to be employed in industry, wealthy, educated, and in favor of Aceh remaining part of Indonesia. Aside from potentially sharing a faith, which may not even be the case, there is little held in common among many of the disparate groups that make up Indonesian society.

All of these characteristics of the history of Indonesia and its current practices combine to create a cultural context for conflict that is both accepting of and expecting violence. There is societal distrust of government and the intentions of other groups. This combines with a lack of faith that government or any of its actors will protect individuals or groups to create a society where violence is the norm rather than the exception.

There have been five conflicts in Indonesia that have met the UCDP threshold of at least twenty-five battle deaths per year. One of these was ideological, centering on the role that Islam should play in the country. The other four were identity-based conflicts in the South Moluccas, West Papua, East Timor, and Aceh. The most significant group challenging the government in the ideological conflict was the Darul Islam (DI) Movement, though the Permestas and the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI) also participated.

The Darul Islam Movement emerged after independence as groups within society fought for different forms of government. In this case, the contention was about whether Indonesia would remain a secular state or transition into an Islamic one. It was an effort to change the Indonesian state’s form and function, rather than to secede from it (G. Brown 2005, 7). According to Horikoshi, one of the most significant factors contributing to the movement was the “personal ambition and charismatic leadership of the DI leader, Kartosuwiryo” (Horikoshi 1975, 60). He reportedly believed that the area of the Indonesian republic was daru’l-harb (the abode of war) and that it was the duty of Indonesian Muslims to engage in jihad (holy struggle) to transform it to Daru’l-Islam (the abode of Islam) (Soebardi 1983). Kartosuwiryo’s leadership was an important aspect in the capacity of the group. He was believed to have mystical powers, and his followers circulated the word that he was selected by “God to become the Imam of the World Caliphate” (Horikoshi 1975, 74). The DI adapted a traditional oath in which the faithful vowed to obey and support their religious leaders so that its members were promising obedience to and sacrifice for the movement and Kartosuwiryo himself (Soebardi 1983). He was not only his followers’ military commander, but also their Imam and a person they believed was vested with magical powers. This mystic perception allowed him to mobilize the poor and faithful Muslims of Indonesia behind the DI.

TABLE 6.1 Timeline of Key Events in Indonesian Conflicts, 1512–2005

Date | Event |

1512–1602 | Portuguese and British join the Dutch colonization of the country |

1602 | Establishment of the Dutch East Indies Company. Dutch became the dominant colonial power. |

1825–1837 | Dutch policy of religious neutrality shifted to favor Christians after Islamic-inspired rebellions (Diponegoro in Java, 1825–1830 and Padri in West Sumatra, 1823–1837) (Arifianto 2009, 76–77) |

World War II | Japanese occupation |

Post–World War II | Aceh: Acehnese initially embraced Indonesian independence but then grew restive as the new country seemed too secular (G. Brown 2005, 2) |

August 17, 1945 | Indonesia declared independence |

1948 | Darul Islam (Islamic rebellion; DI) Movement in West Java (Ricklefs 2003, 49) |

1949 | Aceh: Subdued by Indonesian forces |

December 27, 1949 | Indonesian independence recognized |

April 25, 1950 | Republic of South Moluccas: Rebels declared its independence |

1953 | DImovement engaged government in a short-lived conflict |

1956–1965 | President Sukarno’s era of “Guided Democracy” |

1958 | DI,Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI), and Permesta: Joined to engage in conflict with government |

1959 | President Sukarno dissolved the Constitutional Assembly and declared the 1945 Constitution without the Jakarta Charter (Arifianto 2009, 80) |

1961 | DI, PRRI, and Permesta: Conflict ended |

1962 | Aceh: Aceh received special region status, so it could govern its own religious affairs; Papua: Dutch handed the region off to the un |

September 30, 1965 | Five top generals were kidnapped and killed. The Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), likely with Sukarno’s help, attempted to seize power but failed. This was followed by a purge of Communists and ethnic Chinese, resulting in 500,000–1,000,000 deaths. |

1965 | Papua: Organization for a Free Papua (OPM) initiated conflict with government |

March 1968 | General Suharto removed Sukarno from power and was appointed president |

1969 | Papua: Referendum on independence (likely rigged) was held |

1970s– | Aceh: Transmigration program brought many Indonesian immigrants to Aceh |

1971 | Aceh: Oil and natural gas was found in Aceh, increasing its importance to Indonesia (G. Brown 2005, 3) |

1975 | East Timor: FRETILIN engaged government in conflict |

Aceh: Formation of the separatist Free Aceh Movement (GAM); East Timor: Indonesian military invaded | |

1981 | Papua: Operation Clean Sweep undertaken by government forces |

1984 | Papua: OPM conflict ended |

1982–1985 | Petrus killings: 5,000–10,000 petty criminals were rounded up and killed, their bodies left in public places as a warning by military personnel |

1989 | Aceh: Dispute with GAM reached conflict level |

1966–1998 | Indonesia’s New Order period. Governed largely by Suharto, who was reelected repeatedly in uncontested elections. Suharto’s transmigration policy encouraged those living in populated areas (particularly Jakarta) to migrate to less populated areas, encouraged with land grants to migrants. |

1990s | Aceh: Another peak in transmigration to Aceh from other areas of Indonesia |

1997–1998 | Indonesian economic crisis |

1998 | Suharto regime fell, followed by violent conflict; East Timor: Conflict ended |

1998–1999 | B. J. Habibie president |

April 1, 1999 | Police force separated from the armed forces |

October 1999–August 2001 | Abdurrahman Wahid president |

June 26, 2000 | Moluccas: A state of emergency was declared for Maluku and North Maluku |

August 2000 | Ambon: International and national pressures resulted in the creation of a special joint battalion of troops to deal with problems in the region. Yon Gab troops arrived on this date, but they failed to bring about peace and, in fact, engaged in the violence against civilians (Azca 2006, 440–443). |

September 2001 | Papua: OPM entered talks with government |

2001–2004 | Megawati Sukarnoputri president |

2001 | Aceh: 1,500 died in the violence. This year also saw the most substantial efforts to negotiate a peace (Djuli and Jereski 2002) |

Mid-September 2001 | Aceh: Call to declare the GAM an enemy of the Indonesian state ignited violence |

January 2002 | Aceh: Special autonomy agreement for region went into effect |

First 10 weeks of 2002 | Aceh: More than 300 died in violence |

February 2002 | Aceh: A new military command approved for Aceh, and a decree authorizing a military campaign in the region was extended (Dalpino 2002, 89) |

May 2002 | Aceh: Laskar Jihad (LJ) troops sent to Ambon to support Muslim fighters against Christians. The LJ forces were supported by the military (Azca 2006, 439, 444). |

May–November 2003 | Aceh: Indonesian Aceh campaign. Military killed about 900 GAM members and 300 citizens, arrested more than 1,800 (Charlé 2003, 22). |

October 20, 2004 | Election of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono as president |

December 2004 | Asian tsunami disaster. Aceh: Devastated. |

August 2005 | Aceh: Indonesian government signed peace agreement with separatist Free Aceh Movement (Cochrane 2012) |

Colonial experiences contributed to the religious conflict between Christians and Muslims. Early Dutch policies focused on equitable treatment of the peoples of different faiths in the country. This practice ended after a series of Muslim-led independence movements in the 1800s. After that, the Dutch openly favored Christians, granting them powerful positions in government. The conflict between the groups continued at independence. The Jakarta Charter was a set of clauses proposed for inclusion in the Indonesian Constitution. One clause read that Indonesia would be organized as “a Republic founded on the principles of the Belief in One God, with the obligation of adherents of Islam to practice Islamic law (Shari’a)” (Arifianto 2009, 79). Indonesian Christians were upset by the proposed inclusion as they thought it indicated an impending shift to an Islamic state. When the Charter was removed, Muslims were offended and became distrustful of Christians and secular intentions for the country (Arifianto 2009, 79). Indonesia’s Muslims formed their own political party, Masyumi, with the hopes that they could bring about an Islamic state through the political process, but that failed to emerge (Soebardi 1983). The DI was a country-wide undertaking, but there was limited coordination across the country’s many regions. There were, for example, uncoordinated rebellions in West Java, Aceh, and South Sulawesi.

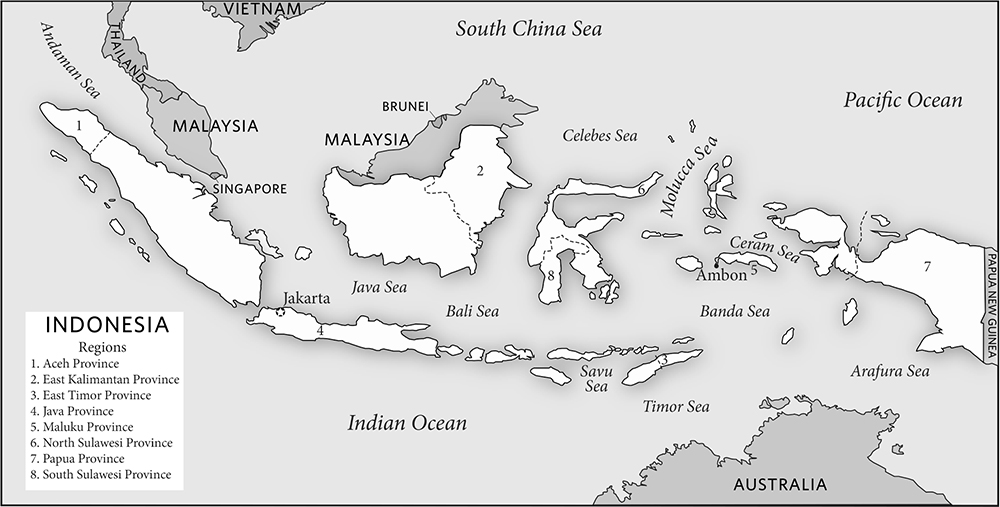

TABLE 6.2 Conflicts in Indonesia, 1953–2005

In 1959, after failed negotiations of the Constitutional Assembly, Sukarno reinstituted the 1945 Constitution without the Jakarta Charter and established authoritarian rule in the country. Conservative Muslim leaders were arrested (Arifianto 2009, 80). The most significant time period for this conflict was 1958–1961.

The Permesta conflict emerged from the rebellious period of the late 1950s in Indonesia. Weakness in the central government had stimulated many regions to seek autonomy. In March 1957, an army commander for Sulawesi and East Indonesia proclaimed regional independence, resulting in conflict from that point to 1961 (Formichi 2012, 166).

By February 1958, the Pemerintah Revousioner Republik Indonesia (PRRI) had emerged as another rebel organization. This one, however, brought together members of the military and groups that were previously seeking a political solution to the movement for Indonesia to be an Islamic state. The PRRI mobilized Masyumi, an Islamic political party. Frustration over the failure to resolve the question of the role of Islam, general mayhem in government, and poor economic performance contributed to the PRRI’S formation (Formichi 2012, 166).

Ethnic conflicts have also occurred as regions of the country with distinct identities fought for independence from the government they perceive as being dominated by the Javanese. These movements overlapped chronologically, resulting in the government facing more than one foe at a time. Major groups associated with the ethnic conflicts include the Republic of South Moluccas (RSM), Organization for a Free Papua (OPM), the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (FRETILIN), and the Free Aceh Movement (GAM).

The Republic of South Moluccas was declared independent by rebels on April 25, 1950. Fighting was relatively short-lived, lasting only about a month, and never escalated to the point of war. During Dutch occupation, the South Moluccas had been given special autonomy and were protected by the Dutch. Once the colonial power departed, the Indonesian military moved to absorb the islands into the new state. The fiercely independent Moluccans rebelled against what they saw as Indonesian colonialism.

West Papua was a Dutch colony until 1962, at which time it was handed over to the UN and then to the Indonesian government (UCDP). One of the stipulations of the handover, referred to as the “Act of Free Choice,” was that Indonesia had to hold a referendum in West Papua to determine if the population wished to remain part of Indonesia or become an independent state. Many citizens in West Papua felt that their culture was not shared with the rest of Indonesia and that they would fare better as an independent state rather than as a minority group in Indonesia. The referendum finally occurred in 1969 with the result being that the region would remain part of Indonesia. The process was designed and controlled by the Indonesian government, which permitted 1,025 elite Papuans to vote to reaffirm Indonesian sovereignty (Djuli and Jereski 2002, 39). This outcome stimulated violence in West Papua as pro-independence forces (Organization for a Free Papua, or OPM) clashed with those who wanted to remain part of Indonesia (UCDP). The violence in the area spanned from 1965 to 1984.

West Papua (also referred to as Irian Jaya in the literature) is the western portion of the island of New Guinea, while the eastern portion is Papua New Guinea. The area is natural resource rich, resulting in interest from the Dutch when it was a colony and from Indonesia after independence. It also was a destination for many Javanese during the Indonesian transmigrasi program, which led to local resentment of the resettled people. The natural resources came to be controlled by the Javanese migrants. The money generated from exploiting the resources was not distributed among the local citizens, but instead went back to the capital and enriched the government and Javanese. This exacerbated tensions. The island itself is separated from Australia by the narrow Torres Strait. Because of this geography, both Papua New Guinea and Australia participated in resolution attempts. Papua New Guinea was impacted by the conflict as the OPM crossed the border to set up bases and launch attacks, which led to some conflict between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea as Indonesian forces followed rebels into Papua New Guinea’s territory (UCDP). Flows of refugees fleeing violence also entered Papua New Guinea, creating challenges for that government.

The region of East Timor received its independence from the Portuguese in 1975. This was followed by violence as citizens who wanted to become part of Indonesia clashed with those who wanted independence. In spite of the fact that the majority of the Timorese did not favor annexation by Indonesia, military actions by the Indonesian government resulted in it becoming a province of the country in 1976. It occupies the eastern portion of Timor Island, which has natural resource wealth on its territory and surrounding seas. The Indonesian government feared that East Timor would become a Communist country. This led to twenty-four years of occupation (1975–1998), with East Timor finally gaining independence in 2002 (UCDP). The rebel group in East Timor was the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (FRETILIN).

The Aceh region is located in the far northwest tip of Sumatra, the largest of the islands that constitute the country. It has been plagued by warfare since the termination of the Acehnese sultanate, with its fight against the Dutch alone raging from 1873 to 1942 (Kurlantzick 2001). It has been one of the most striferidden areas of the country (Tadjoeddin and Chowdhury 2009, 39). At the end of World War II, the leaders of the region supported the formation of Indonesia but were soon dissatisfied as it became clear the new state would be secular. Aceh was subdued by Indonesian forces in 1949, which led to its participation in the Darul Islam Movement in the late 1950s.

Discovery of oil and natural gas in Aceh in the 1970s increased its importance to the country. This served as a catalyst for later rebellion. Aceh is so resource rich that by 1992 it accounted for 15 percent of Indonesia’s total exports (UCDP). By 1998, 40 percent of Aceh’s gross domestic product was based on the oil industry. However, while the region was prospering from the oil resources, its population was suffering. Poverty rates in Aceh increased 239 percent from 1980 to 2002, during which time Indonesian poverty rates overall actually fell 47 percent (G. Brown 2005, 3). The people of Aceh have been frustrated by several factors: the government’s failure to share proceeds of the province’s oil sales adequately with the citizens of Aceh; Javanese control of the country’s politics, to the disadvantage of minority groups; and military repression (Biswas 2009, 132; Bertrand 2008, 441). “Like other peoples in regions outside of Java, the Acehnese resent the fact that Javanese and other migrants seem to enjoy the greatest benefits from prosperity brought by oil and natural gas development in the province” (Weatherbee 2002, 28–29). As has been the case with other regions, the transmigrasi policies of the country have influenced the region’s instability. Javanese were sent to the area to manage government interests in natural resource extraction. By 1990, Javanese born in the region accounted for 56 percent of the domestic population. Indigenous Acehnese (as compared to descendants of Javanese migrants) have dramatically lower incomes, lower educational levels, higher unemployment, and significantly smaller land holdings (G. Brown 2005, 2–7).

As mentioned previously, the Darul Islam Movement grew from the discontent among many of Indonesia’s Muslims at the country not becoming an Islamic state after independence. The government faced a real challenge in dealing with the threat posed by the DI. The ideal of an Islamic state had great appeal to many Indonesians, and the government could not openly speak out against it (Vandenbosch 1952, 183). This conflict is unique as it spread across all of Indonesia while the others were geographically concentrated. In fact, there were occasions when the DI rebels would join with the regional secessionist groups (particularly those in Aceh and South Celebes) in struggles against the government (Weatherbee 2002; Van Bruinessen n.d.). The DI was a national-level movement that consisted of supportive groups in the many different regions of the country. It was particularly powerful in West Java. At times, DI would turn its violence on the citizenry, killing Christians, Communists, or Indonesian nationalists as they marauded through the country. On August 7, 1949, Kartosuwiryo refused to put his DI troops under governmental command and declared the creation of an Islamic state. He argued that the government was committing crimes against Islam, as they had failed to develop an Islamic state at independence. DI evolved to have regional political and military commands in Aceh, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, East Java, Central Java, Jakarta, West Priangan, and East Priangan, and two in West Java (Singh 2004, 50). At this point, the government was too weak to stop the DI’S activities or even to understand the extent to which it posed a threat (Elson and Formichi 2011).

From independence to 1953, the discontent simmered and DI-on-civilian violence continued, but violence and casualties in the dyad between government and the DI were relatively limited. Throughout the time that the DI was powerful, it was supported by the Council of Indonesian Moslem Associations (masyumi), an umbrella political party for the many Islamic organizations in the country that was fostered by the Japanese during their occupation (Horikoshi 1975, 65). Masyumi was a powerful force in Indonesia. Throughout the 1950s it pressured the government to refrain from an oppressive drive against the DI. It feared that if the DI lost power, the Masyumi itself would lose support among Indonesian Muslims and fail to win elections. From 1950 to 1953, the DI’S power peaked as the Masyumi sought negotiated settlement of the dispute, and the military remained reluctant to use force against the group. The Masyumi lost power in 1953 as nationalists and left-wing groups formed a political coalition, disempowering Masyumi and diminishing their ability to support the DI (Horikoshi 1975, 77). Violence by the various DI groups increased in 1953 but still remained at the minor conflict level as DI bands around the country burned homes and other buildings, assaulted rail lines, and destroyed farmland. West Java was particularly prone to instability at this time. Communists and nationalists there held demonstrations demanding that government declare all-out war on the DI and protect the citizens from lawlessness. However, other DI activities were taking place, with varying levels of intensity, in Aceh (which declared itself part of DI) and Celebes. In an August 1953 speech, Sukarno declared DI a threat to Indonesia and called for its destruction by any means necessary (Formichi 2012, 160).

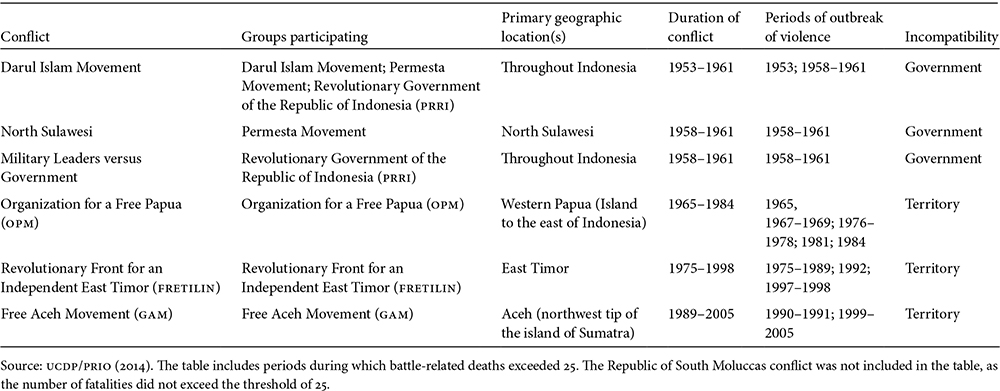

FIGURE 6.2 Patterns of Violence in Indonesia, 1975–2009

The next period of violence for the DI, which was preceded by an assassination attempt on Sukarno, began in 1958. During this period, the DI was joined by the PRRI and Permestas in their activities against the government (van der Kroef 1958b, 73). In January 1958, the Sukarno government was challenged as his top military personnel, many of whom were members of Masyumi and had regionalist tendencies, demanded that he replace his handpicked cabinet (Feith and Lev 1963, 34–35). Discontent spread throughout the country as Sukarno’s legitimacy was challenged. The objection to the cabinet centered on Sukarno’s inclusion of pro-Communists, which was consistent with his program of “guided democracy” policies in the country. Muslim groups in Indonesia were particularly against what was seen as rising influence on government by the Communists.

The problems were exacerbated by the conflict with the Dutch over West Papua (then West Irian Jaya) (van der Kroef 1958a, 59–61). In response to the disagreement, Indonesia moved to nationalize Dutch assets in 1957. Part of this effort included merchant marine assets, which Indonesia was eventually compelled to return to their Dutch owners. The loss of those ships decreased Indonesian shipping capacity and created a bottleneck in shipping that reduced both imports and exports (van der Kroef 1958b, 79–80). This caused economic deterioration in the country, which, combined with the costs of ongoing conflict, resulted in some areas of the country suffering near-famine conditions and water shortages (van der Kroef 1958b).

In February 1958, several generals (referred to at this time as the Padang group) demanded that the cabinet resign, that either Hatta or the Sultan of Jogjakarta form a new government, and that Sukarno return to his constitutionally mandated position (Feith and Lev 1963, 35). The government refused. In response the Padang group declared the PRRI as an alternate rebel government. The fact that the Padang group consisted of military personnel, some of whom were supportive of a role for Islam in governance of Indonesia, as well as being regionalists helps to explain the complexity of the conflict that ensued. Its main actors were the new PRRI, the DI (Islamic state), and the Permesta movement (regionalist separatists). The differences among the participants, however, proved more powerful than their similarities.

The DI was active in fighting that was taking place in outlying areas in support of the PRRI. During this time period the Indonesian military was spread across the islands, and many of its personnel were poorly armed. Concomitantly, the troops supporting the PRRI also lacked the capacity to fight the government (New York Times 1958). This was in spite of reports that the United States had dropped arms into West Sumatra in support of the rebels (Feith and Lev 1963, 36). The DI played a role in carrying out attacks in support of PRRI activities in West Java and South Sulawesi, as well as elsewhere. This was an important factor in diminishing the government’s capacity to fight the DI in the many places it was operational. It was reported that at one point Premier Duanda’s government ordered West Java officers to send troops to Sumatra but was refused on the grounds that they were already all engaged in the West Java conflict with the DI (van der Kroef 1958b, 73).

However, the rebellion failed to become a coordinated effort against the government, as DI in particular proved unwilling to commit its troops, and it lacked internal coordination of its activities (van der Kroef 1958a, 74). One example of this is the failure of the DI leader in Aceh to provide support. At the time Aceh had a special autonomy arrangement with the government, and it was feared that overt support for DI would end that (van der Kroef 1958a, 74). An additional challenge was that some of the PRRI leaders did not support the DI goal of establishing an Islamic state. There was also internal dissent within the DI about tactical issues (van der Kroef 1958b, 74). Furthermore, there was personal dislike among many of the key leaders of the rebellion and disputes over the distribution of arms among the many rebel entities and regions (Feith and Lev 1963, 38). All of these divisions within the rebellion kept it from developing the capacity it could have had if they had merged more effectively. So while the government’s capacity was divided as it was facing varying levels of resistance from region to region, the failure of the rebels to unite deterred them from achieving the capacity necessary to defeat the government. Furthermore, as time wore on, though the DI was gaining support, its troops were fighting further and further away from their communities, weakening their resolve and perception that they were fighting for their own people and interests (Liong 1988, 876).

In April and May 1958 the government managed to retake Padang and Bukittinggi and encountered little resistance from the PRRI. By the end of May the tactics of the rebellion had shifted from traditional warfare to guerrilla activities on the part of the prri. By the end of July there were no significant towns left in rebel hands (Feith and Lev 1963, 36). However, the conflict continued. The poor performance of the PRRI and others in the rebellion in early 1958 has led some to speculate that their declaration of independence was a bluff, and the government successfully called it (Feith and Lev 1963, 36).

The rebel groups managed to coordinate more effectively in 1959 and 1960. Initially, this took the form of radio negotiations among actors (in particular, PRRI and DI) about closer cooperation. These eventually led to a declaration of a new governing arrangement called the Indonesian Federal Republic (Republik Persatuan Indonesia, or RPI). This new federation contained ten states, each of which would be permitted to choose whether it wished to engage in Islamic governance or not, which alleviated one of the major points of contention between the rebel groups (Feith and Lev 1963, 39). This cooperation coincided with the increase in violence in 1960 from minor conflict levels to war. The violence likely emerged from the combined groups’ perception of increased capacity versus the government. The rebels were now able to confront government more effectively.

Supply issues continued to plague the rebel alliance, however. In particular, ammunition was in short supply, with rebels in some areas receiving a daily ration of only ten bullets by 1961. A major factor in the short supplies was the U.S. decision to stop providing support to the rebels in 1960. Low supply levels led to low morale, which further diminished the rebel capacity (Feith and Lev 1963, 40–41). Government offers of amnesty undermined group capacity as young rebels left to return to their normal lives (41). The combined rebellion of DI, the Permesta movement, and the PRRI ended in 1961 with the surrender of many of the rebels. Feith and Lev (1963) indicated that the ratios of arms to men in the conflict were between 1:2 and 1:4, which clearly limited the capacity for the rebels, regardless of how numerous, to effectively confront the government.

Negotiations for conflict termination were carried out by government (first by the army, then by a variety of representatives of government) and varied from region to region. The terms of the agreements were relatively forgiving, allowing rebels to return to civilian life (sometimes with three months’ severance), and some leaders were permitted to return to their roles in government or the military if they swore allegiance to Sukarno (Feith and Lev 1963, 44–46). The DI continued to exist. On June 4, 1962, Kartosuwiryo and most of his top leaders were captured. Violence associated with DI subsequently decreased below the level of minor conflict (Singh 2004, 50). The collapse of the movement was largely due to its link to the charismatic leadership of Kartosuwiryo. However, another important factor was that, without support of the other groups to boost its capacity in the many regions in which it existed, the DI lacked the capacity to challenge the government effectively.

While the DI, Permestas, and PRRI are no longer organized groups that are threatening Indonesia, the country faces continued threats from Islamists and extremists who want it to become a Muslim state. Among the many groups that have been active recently are the following:

• Jemaah Islamiya (JI) was declared an FTO (foreign terrorist organization) by the U.S. Department of State in 2002. It has carried out numerous bombings and other styles of attacks since 2001. A number of Islamist groups have splintered off of JI and engaged in campaigns of violence.

• Jemaah Ansharut Tauhid (JAT) is one successor group to JI. It formed in 2008 and has attacked government members, police, military, and civilians. JAT has also robbed banks and committed other crimes to pay for its activities.

• Mujahidine Indonesia Timur (MIT) has been referred to as Indonesia’s most active terrorist organization and has been linked to ISIL (Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant), JI, and JAT (U.S. Department of State 2015). MIT is based on Sulawesi but has been tied to terror attacks throughout Indonesia (Zenn 2013). It is a relatively small group, with only about sixty members (Alifandi 2015). It was designated a terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department on September 21, 2015 (Kerry 2015).

In addition to these groups, there are a number of supporters of the international Islamist groups, Al Qaeda and ISIL. An estimated four hundred Indonesians are thought to have traveled to Syria and Iraq to join with ISIL. In addition, the country’s recent attempts to end rebellions peacefully includes the release of more than six hundred terrorist prisoners (“Discourse” 2015).

This should not be taken to mean that all Indonesian Muslims are extremists or terrorists. In fact, the vast majority are not. The largest Muslim group in Indonesia is Nahdlatul Ulama, with over fifty million members, which is part of an anti-extremism campaign and has publicly rejected overtures from both Al Qaeda and ISIL (Varagur 2015). A dynamic struggle continues in the country. At present, it is unclear whether extreme or moderate Islam will dominate in Indonesia, but given the large population, it is likely the religion will continue to have influence.

The next conflict in the chronology for Indonesia was over South Moluccas. At the time of independence, many citizens of South Moluccas, including the approximately one thousand military personnel stationed there, thought they would become an independent state. When it became clear that this was not acceptable to the Indonesian government, the military personnel led the revolt, which was carried out through guerrilla warfare tactics (Nawawi 1969, 939). Their proclaimed basis for their actions was the government’s failure to uphold the terms of the Round Table Conference (Yaeger 2008, 216–217). Additional motivations included fear that the military personnel would be targeted for retribution (in particular by Indonesian nationalists) for their role in fighting in favor of the Dutch in the war. The rebels also complained of economic deprivation. Part of the concern centered on the replacement of the Dutch-supported military troops on the island with Indonesian military forces, which would result in unemployment for many of the former military personnel. There were also fears about how the South Moluccan Christians would fare if the country became a Muslim state (Nawawi 1969, 943). Indonesian forces were landed on Ambon, the most prominent island of the region, to bring an end to the rebellion.1

Rebels on Ambon declared that they would negotiate with Indonesia under the auspices of the UN Commission for Indonesia. The rebel capacity was boosted by the support for their cause by citizens of the region, many of whom had served in the Dutch military. The Indonesian government imposed a blockade with the intention of reducing rebel capacity and threatened troop landings if the rebels did not relent. There were between 1,500 and 5,000 trained rebel troops on Ambon alone (Mercury 1950). Negotiations facilitated by the Dutch were unsuccessful. By July 1950, the government had started increasing its capacity in the region by moving troops to islands around Ambon, with a goal of surrounding it. The force assembled by the government was estimated to be 15,000 troops, clearly exceeding the capacity of the rebels, though they were well armed and trained. The Indonesian government initiated amphibious landings, but in spite of their preponderance of power, the rebels on Ambon continued to fight. By October, the UN Commission for Indonesia was bringing international pressure to bear on the government to end the fighting, but the Indonesian government continued to send more equipment and troops into the region. By the end of 1950 the leaders of the rebellion had been captured or killed, which impacted rebel will to fight, an important element of capacity. While fighting continued until 1952, it was not sufficiently intense to meet the battle death threshold of twenty-five (UCDP). Nothing in the research indicates that this conflict has recurred since 1952.

West Papua was given to the Indonesians in 1962 by the United States and the United Nations after the United States brokered an end to an Indonesian campaign to wrest control of the region from the Dutch (Weatherbee 2002, 30). The inhabitants of the region, which is rich in natural resources, were not given an option for independence. The OPM was formed in 1965 by Nicolaas Jouwe, with the intention to “oppose Indonesia and disturb the security of eastern Indonesia’s territory” (“Papuan Leader” 2014). Because of the natural resource wealth of the region, it was a desirable location for people to move to during the Suharto transmigration campaign. The result has been the marginalization of native Papuans, the destruction of their rainforests, and exploitation of the resources of the region (Weatherbee 2002, 30).

The typical tactics employed by the OPM included guerrilla-style attacks on both government forces and industrial sites, which were typically controlled by transplanted Javanese migrants. The OPM was not a very well organized, equipped, or trained rebel force. The Indonesian military repressed the movement with indiscriminate violence, targeting both OPM members and civilians. Tadjoeddin and Chowdhury attribute this relative lack of capacity to both the tribal diversity in West Papua, which undermined efforts to create a united OPM, and the fact that there was not a Papuan diaspora community that could provide funds and other support to the movement (Tadjoeddin and Chowdhury 2009, 40).

Violence met the warfare threshold of more than a thousand fatalities in 1976 and remained at that level through 1978. This followed Australia granting Papua New Guinea independence in 1975, which created concerns in Indonesian government that West Papua would increase its agitation toward independence. The Indonesian government stepped up its activities to expedite development and natural resource reclamation in the region, though none of the benefits achieved from this were shared with the local population. By 1980, the Indonesian government had determined that the Papuans were incapable of managing the oil industry in the region. It removed all Papuans from jobs in that industry and replaced them with Javanese personnel it deemed more skilled (Brundige et al. 2004, 26). When Indonesian authorities did permit locals to have jobs in the oil industry or forestry, they were paid poorly, or even sometimes forced to work for no pay.

In 1981 the Indonesian military engaged in a military initiative called Operation Clean Sweep, in which families and friends of OPM members were targeted with violence. In some cases entire families were killed. The goal of the campaign was to diminish and deter support for OPM activities. Government forces reportedly went so far as to use napalm and chemical weapons against Papuans, which accounted for many of the fatalities (Brundige et al. 2004, 29). The campaign created a major spike in the number of fatalities, which are estimated to have been between 3,500 and 14,000 (UCPD; Brundige et al. 2004, 29). In many ways these activities were focused on diminishing OPM capacity through reduction of the number of rebel troops, diminished public support, and interference with its ability to recruit and fundraise locally. As a result of this campaign, OPM lacked the capacity to challenge the government effectively, and violence levels dropped to below 25 fatalities per year until the late 1990s (UCDP).

During the mid-1990s, violence centered on the copper and gold mines in Freeport. The government has accused the OPM of hindering the economic development of the region. The OPM objected to the fact that the wealth generated by the mines ended up benefiting wealthy Javanese and members of government, with very little of it remaining in West Papua (Australia West Papua Association 1995). In 1998 Suharto stepped down under intense pressure to do so, at least in part due to the economic situation in the country, which was associated with the Asian market problems more generally. The OPM stepped up its activities in the aftermath of his departure, given the perception that the government was significantly weakened (reduced capacity). The Wahid administration (1999–2001) may have increased the level of violence in Papua when, in 1999, he allowed locals to raise the Papuan Morning Star flag, supported changing the name of the province, and promised the area freedom of speech. Locally based armed forces were angered by these moves and created the Papuan Presidium Council (PDP), which was made up of police, academics, and other elites. OPM activities received a boost in support (capacity) from the success East Timor (discussed below) had in gaining independence in 1999. Some saw this as a sign that the government would be more willing to grant independence elsewhere. In fact, a much higher level of autonomy was granted to West Papua in 2001, but this was not enough for the independence-minded Papuans.

In September 2001, the OPM entered into talks with the Indonesian government, which offered an autonomy agreement that the OPM rejected (Djuli and Jereski 2002, 40). The OPM claimed that the people were demanding separation “because of the central government’s discriminative treatment against [Papuans], also human rights abuses and the wide disparity between indigenous locals and migrant people” (40). However, the negotiated settlement was the 2001 Special Autonomy Law for Papua, which went into effect on January 1, 2002, regardless of the locals’ rejection of it (Tadjoeddin and Chowdhury 2009, 41; Weatherbee 2002, 30–31). The PDP declared the area sovereign in June 2002, resulting in an exacerbation of the violence by some members of the military against the civilian population (Djuli and Jereski 2002, 39). One of the fundamental problems of both the Aceh and the Papuan autonomy agreements was the provisions that grant the locals a greater share of the wealth they generate. The problem here relates back to the transmigration process and policies. While the agreements gave more money to the provinces, the control of those funds was vested in the elite, migrant population. The migrants to these areas have tended to gain control of the revenue-producing areas and assets, while the locals have continued with traditional farming activities. Transmigration has made it so that the majority population in both regions is not a local, indigenous population but the Javanese and Madurese migrants (Weatherbee 2002, 31).

In 2015–2016, the Indonesian government focused on a more positive approach to responding to separatist movements, including negotiations, granting of amnesty, and the unconditional release of political prisoners (including some high-profile individuals who had been in prison for over ten years). This approach was implemented in Papua, where the government began working with people and trying to build trust. At the same time, the government threatened the use of force if rebels continued committing acts of violence (Parlina 2016). The threat resonated with civilians, hundreds of which lived in a forest for more than a month in fear of arrest after rebels killed a military officer in 2015 (Somba 2016). The government’s move toward peaceful strategies to resolve separatist problems is a positive one, likely stimulated by both the costs and failures of its previous military approach and the serious international backlash over the human rights abuses committed during those campaigns.

The situation in East Timor began shortly after it gained independence from the Portuguese. The people of East Timor rejoiced in their independence, though not for long. Indonesia declared that the region lacked the capacity to govern itself and offered the East Timorese the opportunity to join the republic. The citizens of East Timor refused. This resulted in violence in East Timor, as those who wanted independence clashed with those who wished to merge into Indonesia. In 1974, the Timorese Social Democratic Association (ASDT) formed as a political party and began mobilizing East Timor’s citizens to struggle for fair wages. The Indonesian government saw this dispute as further evidence that the area was not ready for self-governance, so in December 1975 Indonesia invaded. Large numbers of Timorese citizens fled into the mountains to avoid the Indonesian troops. In July 1976 the region was declared to be an official province of Indonesia (UCDP). FRETILIN, whose primary leader was Xanana Gusmão, formed as the ASDT transitioned itself into a national liberation movement.

Gusmão had started out as an information officer in the ASDT in 1974, became an armed resistance leader in 1978, and became the president of FRETILIN in 1981 (Cormick 1994). He understood that his meager forces were no match for the Indonesian military. Some of the regional groups in FRETILIN had to resort to taking the uniforms and weapons off dead Indonesian soldiers as a means of supplying the effort (Blenkinsop 1998). Gusmão said, “Militarily, we are very realistic, we don’t dream of great military offensives. Our strategy is conditioned by the occupier’s strategy. That’s why our motto is: ‘to resist is to win’—and not ‘to annihilate is to win’” (Cormick 1994).

FRETILIN declared East Timor to be an independent democratic republic on November 28, 1975 (Capizzi, Hill, and Macey 1976). Fighting between government and FRETILIN resulted in at least a thousand fatalities for each year from 1975 to 1978 (UCDP). The Indonesian transmigrasi policy increased tensions as the East Timorese objected to the presence of the largely Javanese migrants and the unfair distribution of the revenues from the new industries.

The Indonesian government has been accused of committing large-scale human rights violations against the Timorese people. Its actions were so violent as to subdue the citizenry, which drove the fatality rate down below fifty per year from 1978 to termination in 1998 (UCDP). Both the United States and Australia supported the Indonesian policies for East Timor as they shared concern that the region would become Communist absent the Indonesian leadership (UCDP). The Portuguese supported the Timorese independence movement, especially after the human rights violations of the 1970s became known. The United Nations began to offer its good offices to mediate the conflict in the 1980s. Guerrilla warfare continued throughout.

After years of fighting, Gusmão was captured in November 1992, tried, and sentenced to jail. He continued to coordinate the actions of FRETILIN from prison, in spite of the harsh conditions under which he was kept (Blenkinsop 1998).

The Asian economic crisis in 1997 and Suharto’s removal from office brought about an environment conducive to UN mediation, with the Portuguese and Indonesian governments participating. FRETILIN never had direct negotiations with the Indonesian government. However, both sides had reasons to support a ceasefire. For the Indonesian government, international actors were putting pressure on them to find a peaceful settlement for the situation. They also were facing domestic unrest elsewhere in the country and needed to resolve the problem in East Timor so they could focus elsewhere. FRETILIN needed to be freed up from fighting in order to raise funds, mobilize more Timorese in support of the group, and reorganize. The group also felt that the international involvement in the talks was a victory for them (Kammen 2009). In 1999, under the watchful eyes of the United Nations, a referendum was held in East Timor over whether they should remain part of Indonesia or become independent. The result of the vote was that 78.6 percent of Timorese (of which over 98 percent participated) voted in favor of independence (UCDP). The one-sided government violence that followed was some of the worst in Indonesia’s brutal history (UCDP). Many blame the human rights violations that occurred on the Indonesian government, which is accused of having utilized local premans to carry out campaigns of terror against the citizens of East Timor (Tanter, Ball, and Van Klinken 2006; UCDP). A UN peacekeeping mission arrived in the country in 1999 and remained until 2005.

East Timor became independent in 2002, at which time Gusmão became its first president, as a representative of the FRETILIN government. Gusmão later became prime minister in 2007 as the head of his own National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction Party (CNRT) and served in that role until February 2015, when he stepped down ahead of the scheduled 2017 elections, in the interest of letting a younger cadre of leaders advance. Elections in 2015 resulted in Gusmão’s CNRT forming a majority unity party by joining with FRETILIN. The position of prime minister was taken over by former FRETILIN member Rui Araujo (“East Timor President” 2015; Jane’s Intelligence 2015). The potential for political instability had arisen again by the end of 2015, however. The president of East Timor, Taur Matan Ruak, was accused of being in the process of developing a new political party to challenge FRETILIN and the CNRT. East Timorese presidents are not permitted to be involved in a political party, according to their constitution. However, Ruak was argued to have been instrumental in the formation of the Peoples Liberation Party (PLP) with the intention of running for prime minister in 2017. In addition to the PLP, the Bloku Unidade Popular (BUP), an East Timorese political party, has formed as a coalition of five smaller parties. The PLP and BUP argue that FRETILIN and the CNRT are characterized by nepotism and corruption (McDonnell 2015). This competition in government is largely positive, however, as it illustrates that groups in East Timor are thus far content to resolve their differences through the political process rather than resorting to violence.

While domestic and international communities cheered the end of hostilities in East Timor, the negotiated settlement created major challenges for the Indonesian government. Many other regions, including Aceh, Riau, and Papua, saw the peace agreement as a sign of government weakness or willingness to compromise. This is believed to have stimulated separatism, which supports arguments in the theoretical literature about civil wars stating that governments with heterogeneous populations may be reluctant to negotiate settlements and set such precedents.

At independence, Aceh was given a great deal of autonomy, but this was withdrawn in August 1950. From these early days the Acehnese rejected the formation of a secular government in Indonesia. According to Schulze, Aceh differs from the rest of Indonesia in that it was an independent sultanate until the Dutch invasion, in its ethnic and regional identity, and its “radical adherence to Islam” (Schulze 2004, 1). This led to its support of the Darul Islam Movement (discussed previously). The Acehnese also became increasingly resentful over time of the migration of people from other areas of Indonesia into Aceh, in particular those that were not Muslim or that came to profit from the oil and mineral wealth there.

In 1976, in response to increasing frustration and government repression, the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) was established. Its primary leader was Hasan di Tiro, who was a descendant of a family that was prominent in Acehnese government. He remained committed to the independence of Aceh and argued that Aceh existed before Indonesia, the Acehnese sultanate was conquered by the Dutch, Indonesia did not exist when the Netherlands withdrew in 1942, and that there was no Indonesian presence in Aceh in 1949 when the Dutch transferred sovereignty of the region to Indonesia (Schulze 2004). GAM’S targeting included Indonesian political structures, the Indonesian economy (which it targeted to increase the state’s fragility), Javanese civilians (which it saw as representatives of the colonial Indonesian will), and the Indonesian military and security forces (Schulze 2004). Di Tiro saw all of GAM’S activities as being defensive military action, which included preemptive self-defense (Schulze 2004, 40).

Most of the leadership exhibited by di Tiro and other GAM leaders was done from abroad, as they lived in exile around the world. The top leadership therefore led through middle-level members of the group’s hierarchy (Schulze 2004). They began a low-level rebellion in 1989 with attacks on military and police assets. It was 1990, however, before the conflict reached the twenty-five battle deaths threshold. This was achieved through the government’s brutal use of force against members of GAM and Acehnese civilians. As predicted by the literature (Bueno de Mesquita 2005; Bueno de Mesquita and Dickson 2007), the government’s repression actually served to increase support (and GAM’S capacity) for the rebels from both the citizens of Aceh and the international community (Biswas 2009). Government tactics ranged from traditional military maneuvers to disappearances and deaths. The period is known as DOM (Daerah Operasi Militer), which has been referred to as a systematic terror campaign that the government hoped would keep people from supporting GAM (Schulze 2004). This round of violence lasted from 1989 to 1991, at which point GAM was believed to be defeated by the government’s preponderance of power. The organization survived because its leadership was in exile, GAM members fled to Malaysia and continued to train in refugee camps, and a new generation of recruits developed because of the brutal tactics of the government. Reaction against DOM was so negative that the territory controlled by GAM actually expanded (Schulze 2004).

As with East Timor, however, the 1997 economic crisis and subsequent departure of Suharto increased instability in the region (UCDP). Both sides were also influenced by the 1999 independence for East Timor. Government was further impacted by subsequent domestic and international pressure to maintain the integrity of the country. Hasan di Tiro became convinced at this time that all GAM had to do was hold their own and wait for the Indonesian state to fail. A GAM fighter once stated that they “don’t have to win the war, we only have to stop them from winning” (Schulze 2004, 34). The government’s heavy-handed treatment of the Aceh rebels was influenced by its desire to avoid another East Timor and to build a reputation of acquiescence to rebellions (Biswas 2009, 132–133, 141). During the late 1990s GAM was more successful than previously in its attempts to seize and hold territory in Aceh, resulting in an increase in capacity as the group was able to raise funds in the dominated areas and ransom kidnapped personnel from industrial sites.

However, GAM suffered from significant factionalization throughout its conflict with the Indonesian government. As mentioned, many of GAM’S primary leaders lived in exile. Perspectives on strategies differed between the exiled leaders in Europe versus those that were in Malaysia or other Asian countries. This resulted in the most significant and persistent splinter in the group, when Majles Pemeritahan GAM (MP-GAM), a group led by Secretary General Teuku Don Zulfahri, who was in exile in Malaysia, broke with GAM. Another split in the group was between the relative level of secularity desired in the Acehnese government. Where MP-GAM followers argued for a Muslim caliphate, others preferred a more secular system of governance. There was reportedly another division within the group between the leaders in exile and the midlevel leadership on the battlefield, with those in exile taking the hard line about independence while those in-country tended to be more moderate (Schulze 2004). Finally, organizationally GAM divided Aceh into seventeen wilayah, or districts. Commanders in each wilayah had significant autonomy, and some even became warlords (Schulze 2004). GAM’S leaders were united, however, in their desire to keep the factionalization of the organization secret. This arrangement held until it became clear that di Tiro’s health was failing (about 1999), and a power struggle emerged among those who wanted to take his place (Schulze 2004).

While over time GAM participated in peace negotiations, it did not engage sincerely. Hasan di Tiro’s goal in the negotiations was to internationalize the Acehnese dispute with Indonesia. About the negotiations, di Tiro is quoted as saying: “We don’t expect to get anything from Indonesia. But we hope to get something from the U.S. and UN. I depend on the UN and the U.S. and EU. . . . We will get everything. I am not interested in the Indonesians—I am not interested in them—absolutely not” (Schulze 2004, 52). He believed that large numbers of casualties would cause members of the international community to intervene on Aceh’s behalf, creating a scenario where pressure on the Indonesian government would be coming from above and below. Because of this, di Tiro interpreted international calls for negotiations, the willingness to hold the sessions outside of Indonesia, and the presence of prominent international advisers to the process as signs of international support for the GAM agenda (Schulze 2004). Both the Indonesian government and GAM continued to engage in violence during periods when peace talks were occurring. Each side feared that laying down their arms would cause them to lose leverage in the negotiations. In addition, both sides had significant factions that believed military victory was the only acceptable solution. The persistent problem was that many in GAM believed that independence was the only acceptable resolution to the matter, while many on the government side rejected independence for Aceh as a possible solution (Schulze 2004). Furthermore, on the few occasions when there was a cessation of hostilities, GAM used the time to recruit, fundraise, train, and acquire arms. This was particularly true during the “Moratorium on Violence,” which was a ceasefire negotiated through the good offices of the Swiss nongovernmental organization (NGO) the Henry Dunant Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue that held from mid-January to July 2001 (Schulze 2004). Indonesian Army chief Ryamizard Ryacudo announced that the cessation of hostilities allowed GAM to grow from 3,000 to 5,000 men and from 1,600 to 2,150 firearms (Schulze 2004).

By 2001, both sides in the conflict realized they could not win. The GAM found itself in a changed environment (due to the international antiterrorism campaigns that followed 9/11) with dwindling support, which reduced its capacity to fight. GAM also felt that there was little support in the international system for further breaking up Indonesia after the loss of East Timor (Biswas 2009, 133). From the government’s perspective, the international system was placing pressure on it, especially as the human rights abuses inflicted in East Timor came to light, to find a peaceful solution to the Aceh situation (Biswas 2009). Both sides became willing to engage in mediation. Crackdowns from the Indonesian military continued as negotiations were being undertaken. The Henry Dunant Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue mediated a ceasefire between the two sides in 2002 (Biswas 2009, 131). On January 1, 2002, a special autonomy agreement, referred to as the legislation of Nanggroë Aceh Darussalam (NAD), was signed by President Megawati and went into effect for Aceh. The autonomy agreement gave the region a much higher level of self-rule and a 70 percent share of the oil and natural gas revenues generated by the region. It also included a provision that Aceh be permitted to enforce Sharia law within the province (Weatherbee 2002, 29).

In spite of this unprecedented level of autonomy, the struggle continued among those who saw full independence as the only acceptable outcome of the struggle for Aceh. GAM leaders argued that they had accepted NAD as a preliminary step, while full independence continued to be their ultimate goal (Schulze 2004). In February 2002, the government established a special military base in Aceh and sent in reinforcements for the troops, increasing its capacity in the region. Over a hundred people died, and human rights abuses were rampant in the violence after the autonomy agreement was promulgated, with even human rights workers and prominent people becoming targets for Indonesian forces (Djuli and Jereski 2002, 42). According to some scholars, fighting in Aceh continued because the autonomy agreement was crafted to satisfy international demands for peace rather than to address any underlying grievances, such as “repression and violations of human rights by the military and police, perception of profound economic justice, and the social change that took place as part of the transmigrasi policy” (Djuli and Jereski 2002, 41). Locals were distrustful that the funds promised will actually be delivered by the government. Furthermore, much of the wealth in the area was controlled by Javanese migrants rather than Acehnese locals, which meant even a 70 percent return of funds to Aceh might not result in any benefit to the indigenous Acehnese.

Due to the continuation of hostilities, the Indonesian government declared martial law in the region on May 19, 2003. The government further increased its capacity in Aceh by devoting over forty-five thousand troops to the region, versus the estimated three to five thousand GAM forces, in an action reportedly patterned after the U.S. “shock and awe” campaign in Iraq. This, combined with the failure of ongoing peace negotiations in May 2003, resulted in a spike in the fatalities associated with the conflict, reaching an estimated 478 in 2003 and 738 in 2004 (UCDP). Outside Aceh, both domestically and internationally, popular opinion was with the government (Kipp 2004, 62).