As the horse was to the Plains People and the dog sled to the Eskimo, so the canoe was to the people of the Pacific Northwest. The coastline here is rocky and heavily forested, making land travel difficult at best. The canoe allowed travel to summer hunting and fishing grounds and efficient transport of people and goods over long distances.

These superbly crafted dugout canoes were beautiful vessels with graceful, curving lines and smooth, well-finished hulls. Canoes were of various sizes depending upon use. Larger ones were fifty feet long and eight feet wide and could carry as much as six to eight tons—some could seat thirty people. The Haida and Makah people were noted for their ocean-going canoes, fashioned with high bows and sterns to cut through the waves. Some canoes were fitted with sails of cedar bark, and later, canvas.

After being neglected for several generations canoes are again being built by many tribes in the region. Tribal leaders have come to realize that the canoe is an important connection to the past and a powerful symbol of Native identity.

In 1989 a flotilla of more than thirty canoes from throughout the region traveled or pulled to Seattle during Washington State’s Centennial Celebration. This canoe journey, called a paddle, showed the participating tribes the power of the canoe journey to unify and instill tribal pride. This Centennial paddle marked the beginning of the resurgence of the canoeing tradition. Since then, annual canoe races and paddles have been held up and down the coast, and yearly canoe journeys to initiate young people into adulthood have been taking place in many tribes.

In 1993 the Suquamish Traditional Canoe Society was formed to help revive the West Coast Salish canoe culture. Since then the Society has joined other Northwest tribes in making an annual canoe journey to various locations throughout western Washington and Canada. Many of these journeys involve hundreds of miles of water travel over many days and nights.

Traditionally canoes and canoe building had a spiritual dimension, and in some tribes the builder practiced a highly elaborate ritual of purification and prayer before and during the carving. It was a highly prized skill that took many years to master.

I want to see the canoes again

I need to feel the rain on my face

And wipe the drops from my eyes

Hug my drum under my jacket

Sing with Lela May

Wake up in the tent

Break camp

Find the next beach.

I would like to stand on the sand

With all the other Tribes

And watch, proud

And full of understanding

As the canoes

Once again bring to us

Our culture

Our future

Look, get your songs ready

See the canoes come

Around the point!

Again.

This is our ancestors

And our future.

Sing out with pride

Again.

—Peg Deam, Suquamish

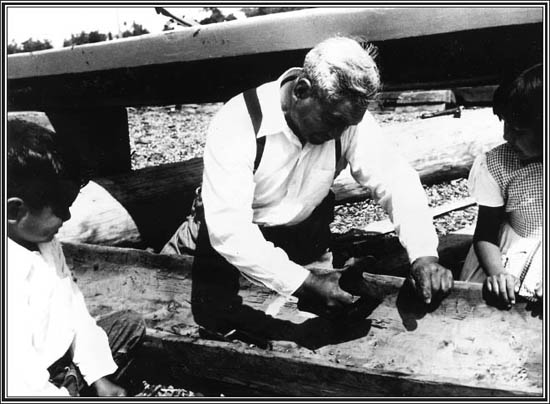

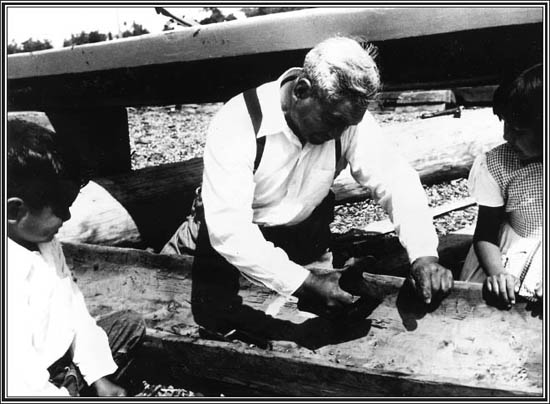

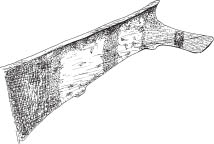

The first step in the building of a canoe was to locate a suitable tree—it had to be growing near water and have a soft place to fall. For moderate size canoes only half the log, split horizontally, was used. For larger canoes, like the war canoe or cargo canoe, a whole log from a 400- to 800-year-old tree was needed.

The best canoes were traditionally constructed from red or yellow cedar. Once down, the log was cut to length, shaped to a rough form, and floated back to the village to be finished. Here the log was shaped with a stone adze and hollowed out with fire and adze. (After Euro-American contact, metal adzes were used.)

When the shape was right, the canoe was filled with water and hot rocks and covered with cattail mats until the wood became pliable enough to be spread to the proper shape. In order for the wood not to split during this process, the sides and bottom had to be quite thin. A midsize canoe 44 feet long was ¾ inch thick on the sides and 1½ inch thick at the keel. Spreading a log in this fashion was quite effective. A log three feet in diameter could be spread to four feet with this method. The total process, from locating a tree to a finished canoe, could take up to a year to complete. (Lincoln, 1991)

The [canoe] journey is a ceremony. The canoe journey is very spiritual. Every motion in the universe has an equal and opposite force. This is a law of physics and a law of spirituality. When we put our canoes in the water, we made a motion in the universe. Before the canoe ever touched the water to initiate that first motion, there was thought. First we think, then we say, and then we do. The ceremony was created from thought, from a dream or vision the Creator put in our minds. Then the thought became words, then action. (Lugwub, Suquamish Newsletter, February, 1997)

In some tribes, chiefs and prominent people were given a canoe burial when they died. The deceased would be wrapped in robes and laid to rest in the bottom of the canoe along with personal effects that they had used during their lifetime—weapons would be put with a warrior or household items with a woman. The canoe was then covered with boards and mats to keep out scavengers and placed on a structure of posts and beams or in the boughs of a tree. After a year the body was removed and put in a cave or taken out to open water and buried at sea. Chief Seattle’s grave site has two symbolic burial canoes supported on a large post and beam structure over his head stone.