The mid- to late-1700s was the beginning of European contact for these indigenous people, almost 300 years after east coast Native people first encountered them. The first written record of contact was in 1741 between a tribe in Alaska and a group of Russian explorers. In 1772, Spanish explorers landed on the Olympic Peninsula to lay claim for Spain. They were driven away by warriors of the Makah people who still live on the northern portion of the peninsula and believe they have claim to this area since the beginning of time.

In 1778, Captain James Cook sailed through these waters with William Bligh (later of H.M.S. Bounty fame) and George Vancouver as junior officers. One of the many places Cook explored was Nootka Sound, off Vancouver Island. While there he wrote in his log: “A great many canoes filled with the Natives were about the ships all day, and a trade commenced betwixt us and them, which was carried on with the strictest honesty on both sides. Their articles were the skins of various animals, such as bears, wolves, foxes, deer, raccoons, polecats, martins and in particular the sea beaver, the same as is found on the coast of Kamtchatka.”

Captain Vancouver returned to this area with his own ship Discovery in 1792. He sailed into Puget Sound to map the territory and claim the area for Britain. In 1805 Lewis and Clark explored the lower reaches of the Columbia River and claimed that region for the United States. And so this beautiful area of the country with its unimaginably rich resources was finally “discovered.” Thus began the destruction of the indigenous Native culture.

During initial contact with Native people, explorers noticed their luxurious fur capes and hats. Inquiring, they learned it was from the sea otter, an animal with the softest and thickest coat of all fur animals. Captain Cook discovered that merchants in China would pay high prices for such pelts. There soon developed an active maritime fur trade, as agents of the Hudson Bay Company of Great Britain arrived to exploit this valuable resource.

The Native people were eager to trade. For their furs they could get iron blades, guns, blankets, and food stuffs that the Euro-Americans offered. It wasn’t long before the Pacific Fur Company of the United States set up trading forts and began to compete with Great Britain for control of this lucrative trade. The Pacific Northwest quickly became a major center supplying furs to Asia, Europe, and cities of the eastern United States. Great fortunes were made, for in those days a bail of sea otter pelts could bring as much as $10,000.

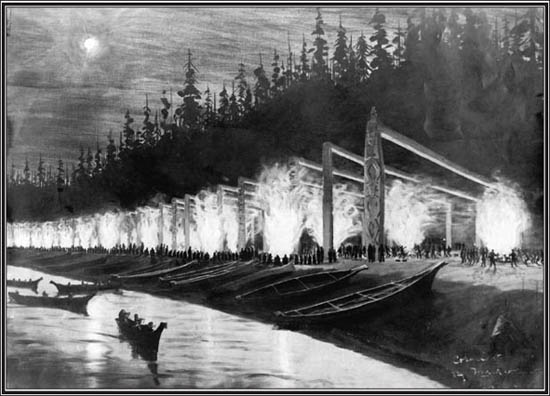

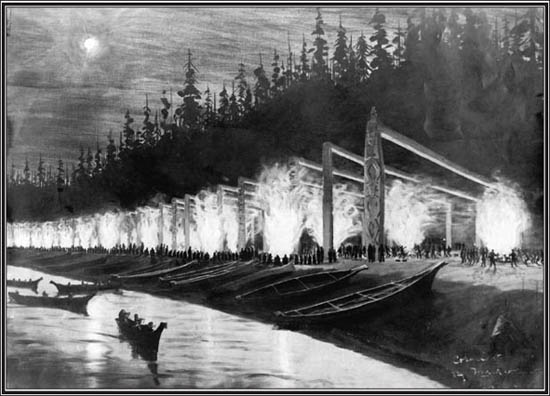

The fur economy continued for more than twenty-five years and created much wealth. Among Native people this wealth stimulated cultural and artistic activity, and many fur trading tribes were able to support full-time artists. In the span of three years, between 1799 and 1802, more than 48,000 sea otter pelts were taken. For the next eighteen years the sea otter was relentlessly hunted. By 1820, the animal was close to extinction and the fur trade collapsed.

Author’s note: The Fur Seal Treaty of 1911 saved the otter from extinction, and today they number more than 120,000.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, this region was experiencing tremendous change. Along with trade items, non-Native people brought diseases such as smallpox and cholera, to which the indigenous population had no resistance. Whole villages were wiped out, and in some areas populations were reduced by as much as ninety percent. The first epidemic of smallpox struck Puget Sound in 1830 and claimed many victims.

In 1841 Canada and the United States settled their border dispute, and the new boundary was marked on the 49th parallel. On January 24th, 1848, James W. Marshall discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California. In the short span of five years, California was transformed from a sparsely populated Mexican province into a multinational melting pot of tens of thousands of people. (Nunis, 1993) This expanding population needed vast amounts of supplies, and because of its abundant natural resources, the northwest again became an active trading center. Canneries were located up and down the coast to exploit the rich fish and shellfish resources, and a thriving lumber industry developed.

By the 1850s the American westward migration was well under way, pushed by a depression and expanding populations back east. An effort by the Federal government to “induce settlements on the public domain in distant or dangerous portions of the nation” resulted in The Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850. This act of Congress allowed new settler families to claim up to 320 acres of land and allowed those already in the region to claim 640 acres. This was before any treaties were made with the Native people of the region.

Surveys were being conducted in the region to locate the best route for a railway line to connect with cities east of the Rocky Mountains. In 1853 Washington Territory, once part of Oregon, was established. Gold was discovered in eastern Washington in 1855 and a few years later in British Columbia, causing an influx of more people.

The region very soon had a growing population competing with Native people for land and other resources. One estimate in the 1850s puts the population of the territory at 5,000 settlers, all looking for the best places to settle.

Like other tribes before them, the Native people here were treated with little regard for their natural rights. Manifest destiny, an ostensibly benevolent policy of imperialistic expansion practiced by the U. S. government at the time, was the operating principal and justification for this exploitation.

In 1850, a federal law was passed authorizing the removal and relocation of all the Northwest tribes from their homelands to an area east of the Cascades. Fortunately this law was never acted upon, and many tribes were able to stay in their accustomed areas when the treaties were ratified. Chief Seattle didn’t know of these and other plans for relocation by the federal government when he spoke to a group of American settlers:

My name is Sealth and this great swarm of people that you see are my people; they have come down here to celebrate the coming of the first run of good salmon. As the salmon are our chief food we always rejoice to see them coming early and in abundance, for this insures us a plentiful quantity of food for the coming winter. This is the reason our hearts are glad today, and so you do not want to take this wild demonstration as warlike. It is meant in the nature of a salute in imitation of the Hudson Bay Company’s salute to their chiefs when they arrive at Victoria. I am glad to have you come to our country, for we Indians know but little and you Boston and King George men know how to do everything. We want your blankets, your guns, axes, clothing, tobacco, and all other things you make. We need all these things that you make, as we do not know how to make them, and so we welcome you to our country to make flour, sugar, and other things that we can trade for. We wonder why the Boston men should wander so far away from their home and come among so many Indians. Why are you not afraid? (Bagley papers)