CLOTH

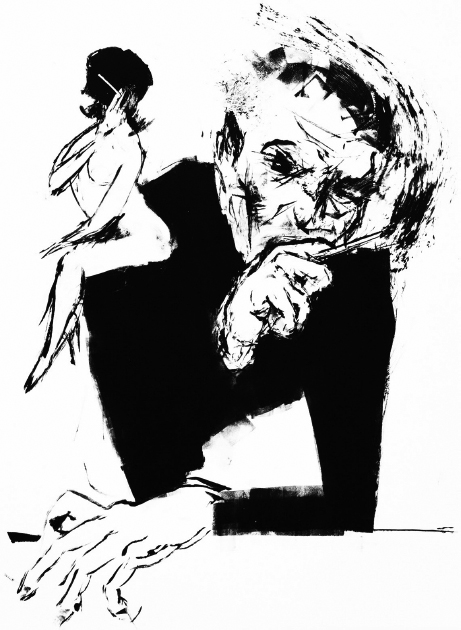

I’VE NEVER UNDRESSED my wife.

Not once have I seen her step out of the bath, climb into a bathing suit, or crawl into our bed unclothed. I can draw her body with my hands. Every dimple, mole, collapse and bulge. In the dark, I see by touch. I know the terrain of her body better than I do my own. Place me in a room absent of light, permit me to touch the faces of five women—unerringly I’d pick Gabrielle’s. My own face among four others, I’d fail the test.

It hasn’t been her choice. I’ve heard some men complain their wives have never appeared before them nude. Gabrielle would express no such reserve. The conditions are mine. Even our wedding night, I insisted her body be absent illumination. My hands store that memory.

Why?

Father’s woman danced nude. I saw her only unclothed and in a turkey trot. Always after everybody had gone to bed. James, my brother, and I’d be awakened by a shrill voice trailing back and forth in the upstairs hallway. Stark naked, she would be twirling and gesturing to her closed bedroom door, spitting out Father’s name. At a Tabernacle Church in our neighborhood I’d witnessed women dancing in the aisles, speaking in tongues as if in a trance, to collapse exhausted onto the floor and shiver paroxysmally.

Father’s woman danced like that, too. But hers was more a dance of curse. Vituperating him who lay awake on the other side of their bedroom door. She’d dip and stride, jump and twirl, point at the hallway light and cry, “You bastard! Tonight, I will jump off the Cement Dam. None of you believe it. But I will show each of you.” Young James would begin crying. I’d tell him to be quiet, and that if she tried to leave the house, we’d follow her.

“She got to jig it out of her system. It’s like the Holy Rollers “Strip the Willow.” They foam at the mouth and collapse. She will, too, back in Father’s bed. Nothing’s going to happen. Now stop your damn bawling.”

Mother lived in the same house, too. Just the four of us. But she never high-kicked, and I suspect Father never saw her naked either. Not that he didn’t want to. He loved women, all kinds of women. A light turned on inside of him when the subject was raised. But not with Mother. Profoundly religious, and clothed tight to her cervix and far below her knees. Black-laced matron’s heels. Hair in a netted bun pulled severely off her forehead, and no makeup—white as the flour she’d crank through her sifter daily. Mother’d chastise Father, James, and me for wandering through the house in a state of undress. “It’s not proper!” she’d cry, running to fetch a shirt or a pair of trousers. James and I figured when we died, Jesus would greet us in a suit and tie. That’s why they’d bury us so, too. Only the naked go to hell.

Mother wasn’t doing the hysteria shuffle at two a.m. It was Lee Ann Daugherty. Curiously enough it was the first time James or I ever saw a naked woman. There had been pornographic depictions of women in literature down at the local gas station. Artists’ renditions on men’s rooms walls. But Lee Ann caterwauling back and forth in the hallway was our introduction to how the opposite sex actually looked indecently exposed. It wasn’t pretty.

Threatening suicide off the Cement Dam that lay a mile up our road, 150-foot concrete wall that once held back the mighty Neshannock River. But decades earlier the Army Corps of Engineers diverted the river, and the Cement Dam now sat out there incongruous in the Hebron countryside, a barrier towering up inside a gorge. Wasn’t a year go by that one or two citizens didn’t take their life by leaping off it into the water-less rubble below. Townspeople began to believe it held persuasive powers, the whole terrain about the land, that if you ventured anywhere near, say even a half-mile, its elegiac pull would draw you to the dam and certain death. Even the utterance of the name frightened the youth of Hebron. Satan paled in power.

Lee Ann thrust its spell into us over her gavotte. Her swooping against the stained and unraveling wallpaper, darting like a moth against the door to our room. Her sobbing an ineluctable grief . . . for what, James nor I were ever certain. Her raw anger directed at Father and even, it appeared, at God. Why had either of them violated her so?

The coda to her lament: “You’ll see. The whole damn bunch of you will see. I’m off to Cement Dam.”

But she never went. Over time Lee Ann would wind down, her sobbing would grow less impassioned, her invectives against the closed door of Father’s room fewer. Until finally, folding into a woman-ball, she rolled into a corner. Unmoving. No more wails, screeches, imprecations or threats. Shortly Father’s door opened. “It’s time to come to bed, dear,” bending low to grasp Lee Ann’s hand. Together they’d glide back into the dark, shutting their door softly.

Bright the next morning, Mother would appear. Her house dress buttoned to her sternum and skirting her calves. A pair of white sheer anklets and string-laced ward shoes. Wearing a gossamer hair net. (Lee Ann’s hair fell to the swale in her back, barely touching her buttocks.)

James and I’d lie frigid in our bed following such performances, listening for any noise we might decipher. Grateful for the peace. Grateful that the dance would not erupt for another month. Grateful that we didn’t have to follow her to Cement Dam. We’d offer a prayer, whispering it between ourselves. “Thank you, God. Lee Ann has flown our house once again. And could You keep her away longer next time?”

Perhaps if we’d been youngsters at the time of the dithyrambs, say five or six years old, they wouldn’t have affected us as they did much later. Lee Ann’s flings, however provocative . . . it was the fact that she associated them with death that queered our vicarious pleasure. Sex, certainly—her out there springing her body off the mahogany-woodwork hallway in the flickering overhead light, the slapping of her bare feet onto the dark shellacked floors, her wailing and moaning, a larger-than-life shadowgraph billowing across the fleur-de-lis wallpaper. Hair moving rope-like about her naked torso, lashing and caressing it, a salt-and-pepper hawser. The fleshy mouth out of which lamentations shaped into mournful entreaties to God and Father. As if a plunge from 150 feet into Abraham’s water-less bosom could be the only succor up to the task.

If this was sex, we were aroused and stricken by it. Father related to both women with characteristic equanimity, however.

Until the day Lee Ann became Mother.

The early morning danse du ventres occurred with such predictable frequency for two years that eventually neither James nor I’d leap out of bed at their onset. We’d lie listening to Lee Ann’s shrieking and body slump, awaiting Father’s soothing voice, cajoling her back into their bed—caressing the door shut. Our prayers of relief had grown perfunctory. We were being lulled into the belief that Lee Ann would never carry out the Cement Dam threat.

Then James and I found employment working for a commissary at a nearby “Double A” ballpark. Three summer nights a week with a double-header on Sunday, several hundred Hebron citizens would pay to watch baseball. He worked the stands with a hot dog dispenser while I managed the refreshment booth. An August evening I was icing vendors’ soda buckets when Father appeared at the admittance gate, summoning me out to the parking lot.

“Seems you better get home, Westley.”

“Why?”

“It’s your mother.”

“What’s wrong with her?”

“Well, nothing yet. But I just think you should stick around the house.”

“I don’t understand. What’s wrong?”

“Like I said, nothing’s wrong . . . yet. I don’t like the way she’s acting.”

“Lee Ann, Dad?”

He shook his head. “She ain’t showed for some time. Now your mother’s begun talking just like her. I don’t like it.”

“Where are you going?”

“Out. You go on home now and be the man. You’re old enough.”

He climbed into his ’36 Dodge sedan and drove off. An ominous cloud of gravel dust in his trail. I took off right behind him on my bicycle. When I entered the house I called out her name.

“Ma,” I hollered. “Ma, where are you?” No answer. Maybe she’s Lee Ann upstairs, fandangoing through our empty bedrooms. Is that what he meant? Or perhaps she was balled up like tumbleweed in the corner of our hallway. And he couldn’t get her to stand up to go back into the bedroom. He spoke about my being a man now. It’s what men do—grab their Lee Anns by the arms when they get this way, and lead them back into the confines of the dark bedroom they share. In the morning they exit as the real people we know. The people who don’t dance to frighten.

Upstairs I could smell the cologne Father’d sprinkled on his body like he always did when we went out of an evening. I saw the imprint of a body on the counterpane in their room, perhaps Lee Ann’s. Though Mother’s string shoes sat neatly paired at the foot of the bed.

“Mother!” The sound ricocheted through the half-light bungalow. The only noise our refrigerator’s dull drone.

The cellar, perhaps. Hanging up clothes on the lines strung overhead. She’s ironing down there and didn’t hear me. But as I ran downstairs and entered the kitchen . . . I froze. Did I want to go down there? Bad things always happen in basements. Rarely in one’s living or dining room. The heinous acts always occur in that raw, undomesticated chamber of the house.

“Mother? Are you down there?” Father’s face—why had he alerted me? What had she done, causing him to shift this time and never before?

At the base of the cellar steps sat a two-burner cast-iron gas grill on cement blocks. It was attached to the main gas feed by a terracotta-red rubber hose. Each summer Mother placed large blue porcelain kettles filled with newly picked tomatoes on its starfish burners. For hours the fruit would simmer into a sauce she’d jar and store for winter meals. The red pulp steaming, bubbling lava-like, popping and spitting red juice onto the white-washed cellar walls. Both porcelain cocks open wide.

She sat limp on a metal stool before the unlit stove, her head and arms buried beneath a chrysanthemum print washing machine cozy. A salmon-shaded chemise stopped at her knees. Bare legs and feet dangled at the sides of the stool.

Alongside lay a crumpled “Till Death Do Us Part” note, addressed to Father and signed by Mother’s closest friend.

Caterwauling like Lee Ann, I gathered her in my arms and carried her out of the cellar, begging that she come alive. Her hair fell loose, brushing against my body each step I took. She felt cold. I cursed my departed father, cursed God, and begged that she not leave me alone.

Gone to Cement Dam in James’s and my absence. And now I bore her body through the light-dying house, wailing. But nobody heard. I laid her on the sofa, thrust each of the windows open to the evening air—then pumped her chest as if I’d lifted her out of a pond. Calling her to make a sound, any sound, even if she’d speak in tongues . . . Oh, God . . . It would be sufficient.

“Please don’t leave us!” Drumming her chest, her small frame bouncing ludicrously up and down on the mohair sofa cushions like a cloth doll. Father’s woman. The Lord-will-meet-us-in-the-hereafter-dressed-like-a-mannequin woman. The I-will-wear-my-faux-pearl-buttoned-chemise-with-black-patent-leather-shoes-and-purse-with-a-silver-clasp woman . . . no Lee Anns allowed in the house of the Lord.

But I didn’t want to be in the house of the Lord. My semi-nude headwater, the rise out of which I’d coiled fifteen years earlier, I willed to pull into the air, beat on her as they once beat on me and James—slapped us against the backside hard . . . before we bawled.

“Christ, Mother, come alive. Goddammit, come alive!” And in my mind I saw myself reaching into her balled-up soul, untangling her arms, and dancing her to the surface, watching her awake to gulp breath—suck the Hebron night air out of the gullies of all the cement dams of this world, God’s fear-and-trembling threshers . . . and ever so fragile, a smile eddied her purple-rose lips.

Me on top of her like I’d ridden my ghost across the mesa of time.

“What did you do that for?” she asked.

For which I’d no answer.