CHAPTER SEVEN

THE INTERPERSONAL THEORY OF SUICIDE

We have explored suicides and near-suicides and identified common risk factors, such as substance abuse, mental health disorders, and access to lethal means. We’ve learned how suicide can be contagious and develop into a cluster, and how a propensity for suicide can be passed down directly through genes and also through the modification of gene expression, called epigenetics. We’ve explored many of the signs of suicide, and learned the importance of opening a conversation with those we fear are at risk. We’ve seen that one should remain with those in a suicidal crisis, remove lethal means from the environment, and accompany them to safety.

Taken together, we can’t help but reach the same conclusion experts do: suicide is highly complicated. And no part of suicide is more complicated than predicting who is planning to kill themselves. The warning signs are almost all we have, but they are not enough. Promising technologies such as PET scans may in the future make anticipating suicidal behavior routine, at least among psychiatric patients who make themselves available for treatment. But for the time being, if a patient makes it to care at all, clinicians have little chance of determining whether they will kill themselves. To say nothing of the majority of suicide victims who neither tell anyone of their plans nor seek medical help.

With a team of researchers, Joseph Franklin, PhD, associate professor of psychology at Florida State University, studied 365 suicide case studies and found that the traditional risk factors we’ve discussed, such as depression, substance abuse, and previous suicide attempts, are not solid predictors of suicide. He said about clinical forecasting, “Nothing was better than luck. Guessing or flipping a coin is as good as the best suicide expert in the world who knows everything about a person’s life. That was a wake-up call for us and for the field as a whole, because it showed that all the work we’ve done over the past fifty years hasn’t led to any real progress in terms of forecasting.”

In fact, in the last half century, scientists, physicians, and therapists in the United States have made little sustained progress in either forecasting or preventing suicides. Crisis hotline centers have been set up in most American cities and a whole new generation of antidepressants has been invented. Yet in 2008, at the start of a national recession, the suicide rate in the US was almost exactly what it was in 1965: eleven deaths per one hundred thousand people. And between 2007 and 2018 the numbers have grown on average by about 35 percent, and about 57 percent for young people between the ages of ten and twenty-four. There was a brief dip in rates in 2019, but by 2020, suicide was back on the rise. Experts agree that in the United States an annual increase in the number of suicide deaths is all but certain for the foreseeable future.

Ahead we’ll look into the possible sources of this crisis, but disturbing trends appear when you examine the rates of major causes of death—suicide, murder, and car accidents—over time. In the 1970s, you were more likely to be killed by someone else or die in a car accident than to kill yourself. Today you are much more likely to kill yourself.

In an auditorium in the psychology department at Florida State University, a seventy-inch projection screen plays an interview with Fonda Bryant. The big screen and speakers amplify her already supersize personality. She’s talking about her four suicide attempts and the pain she felt prior to each.

With uninhibited candor she says, “It feels like a bear is squeezing the life out of you. Your brain, the most powerful organ in your body, is saying you’re a loser, kill yourself, nobody’s gonna care.”

Watching Fonda, at my request, is an athletic middle-aged man with a shaved dome who though sitting down looks large in every dimension, like the college football player he once was.

Thomas Joiner, PhD, the Robert O. Lawton Distinguished Professor of Psychology at FSU, is a rarity among suicidologists—a celebrity. He achieved this status by developing a unified field theory of suicide, a theory he claims explains “all suicides at all times in all cultures across all conditions.” Called the interpersonal theory of suicide, it ought to be one of the Rosetta Stones suicidology has been looking for—a general model that explains suicides and may be able to help anticipate which patients are going to kill themselves.

Joiner’s bona fides include hundreds of published papers, several books, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a tragic origin story befitting the hero he’s become in the world of suicidology. When he was a twenty-five-year-old graduate student in psychology, his father killed himself. For Joiner it was foremost a tragedy and later a puzzle. Then, suicide was seen as a weak person’s out, an escape from the vicissitudes of life for those not strong enough to weather its storms. But Joiner’s father was a former marine, an outdoorsman, a successful businessman—a man who didn’t shirk from hard work and physical challenges. In Joiner’s eyes his dad was immune to pain or frailty of any kind. He was anything but weak.

His death stirred Joiner personally and professionally. He recalibrated his academic focus and, to quote one writer, began “interrogating suicide as hard as anyone ever has, to finally understand it as a matter of public good and personal duty.”

Joiner felt that suicidology needed organizing principles to make sense of its overwhelming complexity. When he and a colleague sat down to count risk factors for suicide—things like genetic loading, alcohol abuse, and childhood trauma—they recorded hundreds. Academically, this was interesting, but for someone who treated patients on a daily basis it was “a chaotic mess.” How could a clinician track patients’ risk factors and figure out which ones might add up to suicide? Joiner realized that risk factors are relevant, but the field needed to discover broader psychological patterns in the lives of people who died by suicide. And the patterns, which Joiner calls processes, should allow his model to help predict lethal outcomes. He created the interpersonal theory of suicide to fill the gap.

In the FSU auditorium, Joiner left his seat and took a stance at the whiteboard up front, a spot where he exuded ease. In his long career, he had probably spent months of his life at boards like this one.

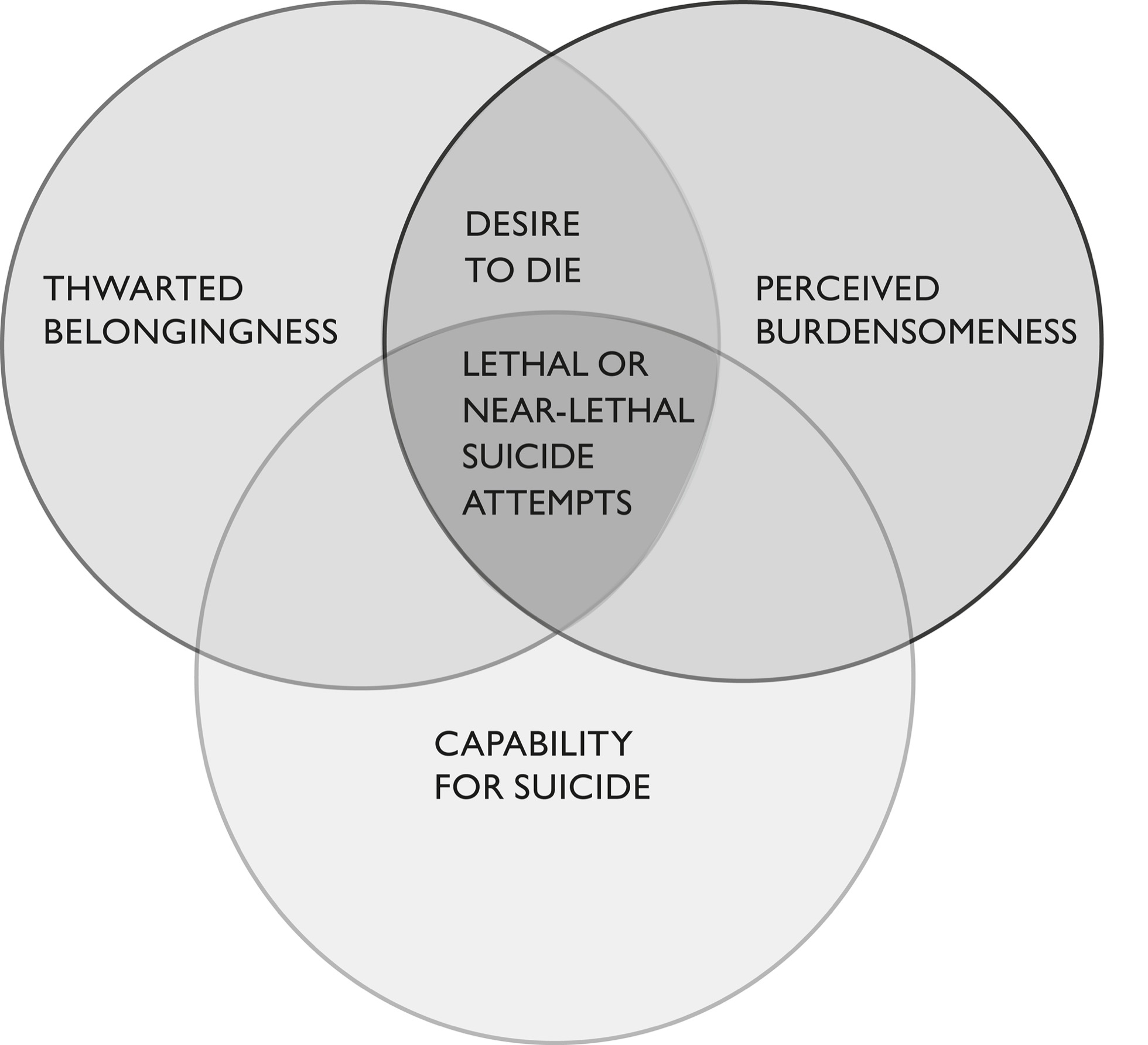

“The interpersonal theory of suicide points to three processes that are key, and the idea is that when those three processes all converge in the same individual, that’s when death by suicide becomes likely.” Joiner drew a large circle and labeled it Perceived Burdensomeness.

“The first process is perceived burdensomeness. That’s the idea that one’s death will be worth more than one’s life to other people. The perception of this feeling is true, though in reality it is almost never true.”

Being a burden to others is a powerful idea but not quite as simple as it seems. What constitutes burdensomeness in the context of a family? Of a community? One might be a financial burden by not helping to support oneself or family members. One could be an emotional burden by consistently engaging in arguments or demanding attention. On the Flathead Indian Reservation, Kimberly Swaney’s boyfriend, Dave, was an argumentative, disruptive force within Kimberly’s household, so much so that she asked the police to remove him for treatment. Whether or not Kimberly and her daughter would have agreed, Dave might easily have viewed himself as a burden before he killed himself.

Michelle Matt dearly loved her brother, John, and would never have labeled him burdensome. But he was addicted to drugs, had clocked at least one stint in rehab, and often changed jobs. It’s not hard to imagine that he thought of himself as someone who contributed nothing but disorder to his loved ones before he too killed himself. A burden.

In his seminal book Why People Die by Suicide, Joiner more closely defines “burdensomeness.” One feels like a burden, Joiner writes, when one feels incompetent and ineffective, and worse, unfixable. In other words, we have a deep need to be competent and effective—to be good and impactful at our work, at our caretaking, at key aspects of our lives. Our competence permits us to contribute to our social group emotionally and materially. When none of this is true, and there’s no way to repair it, we feel like a burden. It bears reiteration that the perceived harm to others is magnified by irregularities in the brain, as described by Dr. John Mann.

What happens then? In this merciless view of yourself in these circumstances the only alternatives are to continue sapping the love and energy of those around you, making them and you feel even worse, or taking your own life. Getting help and recovering aren’t on the table.

Fonda Bryant claimed that she was doing her best as a mother but reasoned that if she killed herself, “My son would be better off.” Generally, being a good mother and suicide are not compatible, but as Mann might argue, these sorts of ideas make sense to a mind reconfigured by suicide-grade depression. I found Fonda Bryant to be a doting mom to her son, Wesley. Wes is the too-rare son who genuinely enjoys hanging out with his mother. Their loving banter is life-affirming. As a boy of twelve, would Wesley have been better off if Fonda had suddenly taken her life, leaving him to be raised by members of their extended family? The pain he would’ve felt at his mother’s suicide isn’t hard to imagine. It would have been crippling and disorienting and it would probably have never really gone away. The impact on his development, and how he might have fared within a family of relatives, is impossible to gauge.

Greg Whitesell never discussed feeling like a burden to me. But after he was prevented from killing himself, he recognized that his death, not his life, would have imposed a burden on the lives of his friends and family, particularly his mother. He said, “I was only worried about myself, but my mom would be living the rest of her life without me. My pain would just be ending, but everybody else’s around me would just be starting.” As we’ve noted before, the catastrophe of losing a loved one to suicide dramatically increases the odds of taking one’s own life.

Joiner holds that perceived burdensomeness is the idea that you strongly believe “everyone would be better off if you were gone.” He said, “It’s important to underline that word ‘perceived,’ because the idea is not that suicide decedents are actual burdens. I would never say such a thing, that is not my take on it. My take, rather, is that the soon-to-be suicide decedent has misperceived things. They think they’re a burden on others and reason that ‘if that’s true then it follows that if I die I would remove the burden from everyone.’ But they’re mistaken about that. The tragedy of suicide is they don’t realize that they’re mistaken and they die on that basis.”

However, in the past some people who killed themselves were not quite mistaken. Joiner points out that some historical cultures considered elderly people an excess cost to be respectfully done away with. These individuals may view their death as a way to alleviate their burdensomeness on others. Eskimo, ancient Scythians, and many other peoples separated by geography and time practiced versions of “senicide,” or the killing or abandonment of the elderly, and enacted them especially during times of famine.

Senicide is connected to the concept of altruistic suicide, which occurs when people are so integrated into social groups that they lose their sense of individuality and are willing to give up their lives for the good of the group. Military history records many instances of soldiers falling on time-fused grenades to save their comrades. Joiner’s theory holds that a sense of obligation to others—not the goal of killing oneself—is a form of extreme burdensomeness that drives altruistic suicides.

With regard to Fonda Bryant, Greg Whitesell, and others we’ve discussed, it’s important to point out how internal the feelings of burdensomeness are, that being an unredeemable burden deserving self-execution is a construct of an unwell mind. In Joiner’s model, burdensomeness brings about grueling psychological pain and shame. But it is not sufficient to bring about death. Suicide has two more formidable weapons in Joiner’s model, and it needs all three to kill.

At the whiteboard, Joiner drew another large circle, which overlapped the first in an almond shape. He labeled the circle Thwarted Belongingness. He said, “Thwarted belongingness is really just a long way of saying loneliness. And mainly it’s the subjective element of loneliness, not the objective one. The idea is not so much that people’s worlds are literally unpeopled but they feel subjectively their internal world is unpeopled.”

Loneliness, or lack of belongingness, also calls for fleshing out. In Joiner’s view, like burdensomeness, loneliness reflects the absence of a bedrock need: to frequently interact with those who care for you. What’s more, those interactions should be positive ones, and the people who care for you should represent stable relationships, not “a changing cast of relationship partners.”

Joiner told me, “Say for instance there are popular high school students or college students who are objectively popular and yet they feel very lonely despite their popularity. Internally they feel alienated and lonely and die by suicide at times, leaving everyone so puzzled. ‘How could that be?’ ” Joiner looks legitimately confused. “They were popular. And yet they didn’t feel that way about themselves. They felt lonely.”

No one better epitomizes a popular high schooler than Arlee Warrior Greg Whitesell. Describing his feelings on the night he almost killed himself, he said, “Lonely. Really lonely, like I knew I had a lot of people on my side, I knew I had a lot of people that cared…but I was just pushing them away…”

It has become a cultural cliché that popular personalities who are much loved and presumably have no shortage of friends nonetheless die by suicide. Loneliness imposed by fame is often implicated. “I have very few friends,” Marilyn Monroe once told an interviewer. And about her childhood, “I often felt lonely and wanted to die.” In 1963 she died by overdose. Shortly before his 2018 suicide, author and TV celebrity Anthony Bourdain texted to his wife, “I hate being famous. I hate my job. I am lonely and living in constant uncertainty.”

If loneliness kills, connections can keep us alive. As you may recall at the powwow on Patty and Billy Stevens’s spread in Montana, Patty’s granddaughter Erica told me she thought about suicide every day. She said only the pain it would cause her family keeps her from killing herself. And that’s a feeling she knows well—her father had killed himself just three years before.

As we’ve seen, for people like Fonda Bryant the connections conferred by church membership and having children are protective. Connection, or belongingness in Joiner’s terms, is a persistent protector that reduces the odds of suicide. On the other hand, thwarted belongingness is an odds-raising condition.

For example, being married is a protective buffer, but being single nudges your odds in the other direction. Getting divorced is a double whammy because it supports feelings of incompetence as a spouse and can cost the divorced their primary social connection and potentially children and friends, to say nothing of adding a possible financial strain. Generally speaking, being pregnant is a plus. Interestingly, so is being a fraternal or identical twin (but parents of multiple births are more likely to be depressed or anxious). Conjoined twins should be the exemplar of connectedness, but they haven’t been studied.

Suicide rates tend to fall after big events experienced together by a lot of people. This is called the pulling-together effect. It helps explain why there are fewer suicides on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Super Bowl Sundays, when groups of family and friends get together for a common purpose. The suicide death rate dropped by 5.6 percent between 2019 and 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck. For 180 days after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, suicide rates in New York fell “significantly.”

Now two ominous circles dominate Joiner’s whiteboard—Perceived Burdensomeness and Thwarted Belongingness. Joiner gives a name to the almond-shaped oval where the circles overlap. He writes the Desire to Die. In other words, when these two psychological states exist in someone, they want to die but they do not necessarily kill themselves. Dr. David Jobes, who created the suicide prevention strategy CAMS (Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality), cowrote a paper with Joiner that concluded that each year, there are on average 50,000 suicides in the United States and about 1.5 million attempted suicides, but there are about 15 million people who suffer from suicidal ideation—persistent, agonizing thoughts about killing themselves. Jobes says, “That’s a lot of unnecessary suffering.”

In Dr. John Mann’s view, these individuals probably suffer from the brain abnormality that causes depression, plus the abnormality that causes suicidal ideation. But while their chances of suicide are dramatically enhanced, they don’t kill themselves. In Dr. Joiner’s view, these sufferers lack a psychological state that everyone who kills themselves has, including his own father. Joiner calls it the Capability for Suicide. He draws and labels the Capability for Suicide, the third and final circle in his suicide model.

While the other two processes set the stage for suicide, and untold suffering, it’s the capability for self-destruction that completes the lethal puzzle.

Joiner said, “The capability for suicide has three elements and one of them is the fearlessness of death itself. The way I think about it is that it’s natural to fear death. Creatures the world over avoid and fear death. We have brain circuits that lead us to avoid states like physical pain and illness and death itself. It’s natural. And so one of the puzzles of suicide is that people are approaching death largely without fear, or at least they’re able to stare down that fear.”

Capability also requires tolerance of physical pain. Joiner said, “A lot of suicide methods are painful, not all but most. People imagine overdose scenarios won’t be painful, then get surprised by the ordeal of it. So there are three elements of capability—fearlessness of death and physical pain tolerance, and finally pragmatics. How do you do it? A lot of people don’t know how to operate a firearm, for example. An insight of the theory is that if you don’t have the capability, it really doesn’t matter how much desire for suicide you have, you’re not going to be able to actually die. You’ll feel a lot of anguish and that’s an important thing in its own right, but you’ll be protected from the worst outcome of all, death, because that final piece is not in place.”

This strikes me as cold comfort. To have all the agony of suicide while desperately sought relief is out of reach. It almost seems like cruelty heaped upon cruelty. But of course this is shortsighted thinking. There are solutions for suicidal ideation, and we’ll explore some. People with all sorts of mental health issues do get better and go on to live satisfying and happy—yes, happy—lives. Greg Whitesell and Fonda Bryant are two such people, and I’ve spoken with others. The relief that death would bring is no relief at all but a transferal of pain, like waves in a lake caused by an asteroid, not a pebble. Waves that will cripple or even hasten the deaths of those closest to you.

How, then, does one acquire the cornerstones of capability, fearlessness of death, and tolerance for pain? As it turns out, mostly by practice.

In Why People Die by Suicide, Joiner writes, “A main thesis of this book is that those who die by suicide work up to the act. They do this in various ways—for instance, previous suicide attempts…. They get used to the pain and fear associated with self-harm, and thus gradually lose natural inhibitions against it.” A prior suicide attempt is the leading indicator of suicide for this reason—individuals often try repeatedly and gain proficiency.

Recall that Fonda Bryant said, “To be honest I attempted suicide four times. Two times where I just thought this would be the best way for me and two times where I actually had a plan.”

The fourth time, in 1995, Fonda had fine-tuned her approach for conclusive results. She never got that far because her aunt Spankie saw the signs and had her committed. But what about Greg Whitesell and Chris Dykshorn? Neither had a history of suicide attempts. Neither worked up to the act. But as we’ll see, in Joiner’s view preparing for suicide is a big tent that contains those who grow accustomed to pain but also those who inflict pain and violence on other beings. Take people who’ve grown accustomed to pain and experience higher suicide risk than average. They include athletes, intravenous drug users, prostitutes, tattoo aficionados, bulimics, and those who engage in self-cutting. They are people to whom pain doesn’t have the customary sting. Studies have shown that people who are suicidal have higher tolerances for extreme temperatures of heat and cold and for electrical shock, and can endure more pain as the result of traffic accidents. Even preschoolers who have displayed signs of wanting to kill themselves show less pain and crying after getting hurt than a control group.

Hunters, physicians, and military personnel become habituated to acts of physical intrusion and violence, and also suffer from higher than average suicide risk. Both Greg and Chris hunted and came from hunting cultures. In Greg’s case, hunting deer and elk is a deeply embedded feature of Native life in Montana. It’s not a stretch to say most adolescents and adults on the Flathead Indian Reservation are familiar with firearms and with hunting and butchering animals to fill their freezers. Hunting is also a big part of rural life, and as a farmer, Chris Dykshorn was accustomed to slaughtering farm animals and game for the table. And he was an avid fisherman. Chris killed himself with the rifle he had used to hunt deer. Greg planned to shoot himself with his hunting rifle, but fortunately he was interrupted.

In Joiner’s view, people get used to the pain and fear associated with self-harm in other ways besides hands-on experience. Joiner reports that rock icon Kurt Cobain obsessively watched a video of a politician shooting himself to death on live TV, perhaps preparing for his own suicide by gun. He was reportedly afraid of needles, heights, and firearms; however, he gradually trained himself to inject drugs, climb high above his stage on scaffolding, and recreationally shoot guns.

Joiner isn’t quite finished with the whiteboard yet. Overlapping in a textbook Venn diagram are the three circles of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide: Thwarted Belongingness, Perceived Burdensomeness, and Capability for Suicide. The first two intersect in an oval shape labeled Desire to Die. Now Joiner labels the small triangle where all three circles converge. If Hell has a center, this is it. He labels it Lethal or Near-Lethal Suicide Attempts. It is here at the convergence of three psychological processes that attempting to kill yourself becomes at least very likely, at most a certainty.

Since Joiner first introduced it in 2005, the interpersonal theory of suicide has become psychology’s most debated and commented-upon suicide model, though to be fair, there aren’t that many. Joiner has rebuffed many critics, acknowledged others, and revised the theory as it garnered adjectives from the psychology community such as elegant, insightful, and effective. It has fans and detractors around the world, but it’s been thoroughly tested and generally found to measure up.

The theory’s major achievement is that while it acknowledges the risk factors that have been linked to suicidal behavior, it doesn’t get bogged down in them. It suggests that we instead take a step back and focus on the impacts of those factors on the mental state of individuals. What’s happening in their internal, subjective reality? For therapists, that’s an invaluable tool. Broadly, it permits them to determine which patient has a foot in any of the circles. Who is challenged by feeling like a burden? Who is painfully lonely? Who has both feet planted in the center circle and probably won’t live long without speedy intervention? Interestingly, of all the links offered by the theory, it’s the one between feeling like a burden and having capability that critics find most persuasive. Apparently, extreme loneliness doesn’t hurt us as much as burdening others.

If therapists can anticipate with only 50 percent certainty which of their patients will kill themselves, it would seem certain that applying the theory would tip the odds toward identification and survival. Despite how robust his theory has proven to be, however, Joiner doesn’t fully buy this conclusion.

“You’re asking yourself the impossible—to try to identify up front who will kill themselves and when. It’s beyond us. What you can do is have a sense of where people are on a spectrum of risk. And once you know that, there are actionable things that you can do as a consequence. It’s still very challenging because the array of risk factors is so variable. But I think the value of the theory I’ve developed is that it tries to boil that down a little bit and make it more manageable.”

Joiner’s life’s work has grown beyond his landmark theory to training future clinicians and researchers. What began as a quest to understand his father’s self-destruction has grown into a mission to help prepare the next generation of suicidologists to take on America’s least understood and most painful epidemic.

Joiner told me, “This theory, this day-to-day work really is not about my dad’s suicide anymore. What it’s about is the fact that tomorrow in the United States, over one hundred families are going to be bereaved by suicide. One hundred. Just tomorrow. And then the next day. And then the next day after that. And so on and so forth. And that’s just in our one country. That’s a human tragedy, and I want to prevent that.”

If you are thinking about suicide or if you or someone you know is in emotional crisis, please call or text 988 at any time to reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline for confidential, free crisis support.