CHAPTER EIGHT

STABILIZATION AND SUICIDE-FOCUSED INTERVENTION

Emergency treatment of people who are suicidal in the United States is a patchwork of services that differ from state to state and even county to county. There is no working national policy in place for suicide treatment or prevention. This is in part because the US Constitution does not explicitly delegate health care concerns to either the states or the federal government. The Tenth Amendment holds that powers not assigned to the federal government are reserved for the states or the people. Suicide treatment therefore varies, depending on what state you’re in. Presumably the federal government could take control of suicide prevention just as they’ve taken charge of monitoring workplace safety standards through OSHA (the Occupational Safety and Health Administration) and the production of drugs through the FDA (the Food and Drug Administration). But federal powers are more likely to leave specific decisions to the states. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic the CDC, a federal agency, issued guidelines, but decisions about mask wearing, social distancing, and school closures were made by the states.

As it stands across the nation, a suicidal person might expect one or two nights in an emergency department under observation, and a therapy session that may or may not be conducted by a mental health professional. Before the patient is released, he or she may receive a referral to a professional, but once released, hospital staff generally will not follow up to inquire about how they are feeling or if they are receiving therapy. Once discharged, many patients do not engage in follow-up care, which puts them at a greater risk for suicide. As we’ve discussed, there is a dangerous gap between emergency psychiatric treatment and vital follow-up therapy.

But whether those follow-up therapy sessions are weeks or months away may make no difference if the patient has no health insurance or cannot afford their prohibitive cost. As we’ve learned, there are paths to low- or no-cost mental health care, and we’ll discuss one ahead. However, with few exceptions, they are complicated for anyone to navigate, more so for someone in the aftermath of a suicidal crisis or who lacks funds. As Erica told me on the Flathead Indian Reservation, “If you’re not rich you might as well just die.”

That’s the tragic state of affairs for many people suffering a suicidal crisis, to say nothing of other mental health conditions, here in the nation with the world’s largest economy. Again, in some states and some counties within states, the situation is better, sometimes much better. But generally speaking, a deficit in mental health care costs the lives of countless Americans. Their families, friends, and loved ones subsequently bear suicide’s traumatic aftershocks.

Fortunately, a new kind of help is on the way in every state. Sponsored by US senators Roy Blunt and Debbie Stabenow, the Excellence in Mental Health and Addiction Treatment Act in 2014 provided funding for Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs) around the country. Every state receives money for mental health clinics in their communities, paid for by Medicaid and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a branch of the US Department of Health and Human Services. The money comes with strict conditions. CCBHCs are required to provide a comprehensive set of services, which include 24-7 crisis support, outpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment services, immediate screenings, risk assessments, and diagnoses, care coordination, and partnerships with emergency rooms, law enforcement, and veterans’ organizations.

What this can mean for individuals in suicidal crisis is breathtaking. Any adult or child who walks through clinic doors can receive care whether they can afford it or not. For homebound patients who have a CCBHC in their region, a mobile crisis team will be dispatched to provide care. People in urgent need but not imminently suicidal will receive an appointment within twenty-four hours. For more routine mental health needs, patients can get an appointment within ten days. Currently, there are 480 CCBHCs across forty-nine states and territories, with plans to add more centers every two years until at least 2025.

David DeVoursney, MPP, a division director at SAMHSA, heads a department with hands-on input into CCBHCs. “I’m really excited,” he told me. “This effort is really hopeful. Since the 1960s, there’s been a long narrative of taking mental health patients out of institutions and serving their needs in outpatient facilities. The second part of the plan never happened. Finally it’s coming about. And CCBHCs are our best hope of developing those services.

“To be able to solve this decades-old problem with the mental health care system is amazing.”

If CCBHCs sound too good to be true, they kind of still are. While the clinics number in the hundreds, they’re not evenly distributed across the country, and for many people, care can be prohibitively distant. The federal government has had trouble consistently funding the clinics, which are often run by local governments or nonprofits. This has made it hard to keep staff and pay for services.

Nevertheless, CCBHCs are a welcome bright light in our nation’s murky patchwork of suicide and mental health interventions.

Fortunately, there is a tool that is available to almost everyone in a suicidal crisis who reaches care, and it doesn’t suffer from funding or staffing problems. This simple intervention is used in emergency departments and clinics across the United States and abroad and has saved innumerable lives. It even meets Denmark’s laudably high standards for mental health care and is used throughout that country. It’s called the Safety Planning Intervention, and it was developed in 2008 by clinical psychologists Drs. Barbara Stanley and Gregory Brown. They explored the critical flaw in suicide care—the time gap between a patient’s visit to an emergency department and the initiation of critical therapy sessions—and found it to be a dangerous place indeed. A 2017 study concluded that during the first three months after discharge from a psychiatric hospital, a patient’s suicide rate is about 100 times greater than average. A 2019 study showed that for a year after their visits, Californians treated at an emergency department for deliberate self-harm had a suicide rate 57 times higher than average.

Barbara Stanley is a gifted psychologist and professor who told me, “The Safety Plan Intervention came about because there was a huge dearth of evidence-based interventions to prevent suicide. Which is really surprising because there is no problem in psychiatry that has greater mortality than people who become suicidal.” She added, “There was a lot of room for a brief intervention that clinicians could use and make accessible to many people.”

To fill that empty room, Stanley and Brown created the Safety Plan Intervention, a list of strategies that will help people who are suicidal get through a suicidal crisis. The intervention involves the clinician and patient collaboratively completing a safety plan form to identify coping strategies and resources that can be used whenever they feel like a suicidal crisis is emerging. It works like this.

At a conference table in the department of psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Stanley and Ron Joss are deep in conversation. Joss is a real estate agent in his forties with salt-and-pepper hair and a hangdog demeanor. Yesterday he tried to kill himself by overdosing on pain medication. Stanley assesses his suicidality by having him reveal the facts of his attempt.

Distracted by his recent divorce, Joss has seen his home sales slip and his boss told him his job was in jeopardy. On top of that, his ex-wife moved out of state with their two children, and he’d had painful knee surgery, which had not healed well. He’s also in recovery for alcohol abuse. In tremendous emotional distress, Joss tried to take his own life. When he missed a scheduled phone call with his children, his ex-wife intervened.

Stanley listened carefully to Joss’s story about how the crisis unfolded and then resolved. It escalated to the point of overdosing and then diminished once Joss was rescued by his ex-wife and brought to the hospital to see Stanley.

“Things really snowballed for you, didn’t they?” said Stanley. She tells Joss she’s sorry he felt so bad that he wanted to end his life but is glad that he is willing to discuss what happened. “Would you be interested in learning about a tool that could help you through rough times?”

Joss answered, “Absolutely. I didn’t want to die. I just wanted to stop the pain.”

Stanley said, “That’s good to hear that you actually didn’t want to kill yourself. It sounds like it would be helpful to discuss some strategies to get through a crisis without acting on the urge to die.” Stanley went on to tell him, “There are six steps on the safety plan, and the first step is to identify warning signs. Warning signs are thoughts, feelings, or behaviors that tell you you’re headed for emotional trouble. So now we’re gonna identify your warning signs so that you know when you need to grab the safety plan and start using it. We don’t want you to make another suicide attempt, okay?”

Joss nodded.

“And what are some of your warning signs? What made you think about hurting yourself?”

“My boss. When he threatened to fire me. It brought up everything else that had been going wrong. And it just made me angry at myself and it kept building up.”

“How did that feel?”

“It was tight and numb at the same time. It’s like a ball of numbness in my chest, a ball of darkness. And an overall feeling of dread.”

“And that happened at work?”

“No, when I got home. I was trying to figure out what I could do to make myself feel better. And the more I thought about how to get out of the funk I was in, the hole I had dug for myself just kept getting deeper.”

“How awful.”

“And it just got to the point where I thought my kids would be better off without me. I couldn’t think of a single person in my life who wouldn’t be better off if I was just not around.”

Both doctor and patient fell silent. Even the seasoned Stanley seemed at a loss over Joss’s bleak assessment of his own value.

“So I swallowed the pills.”

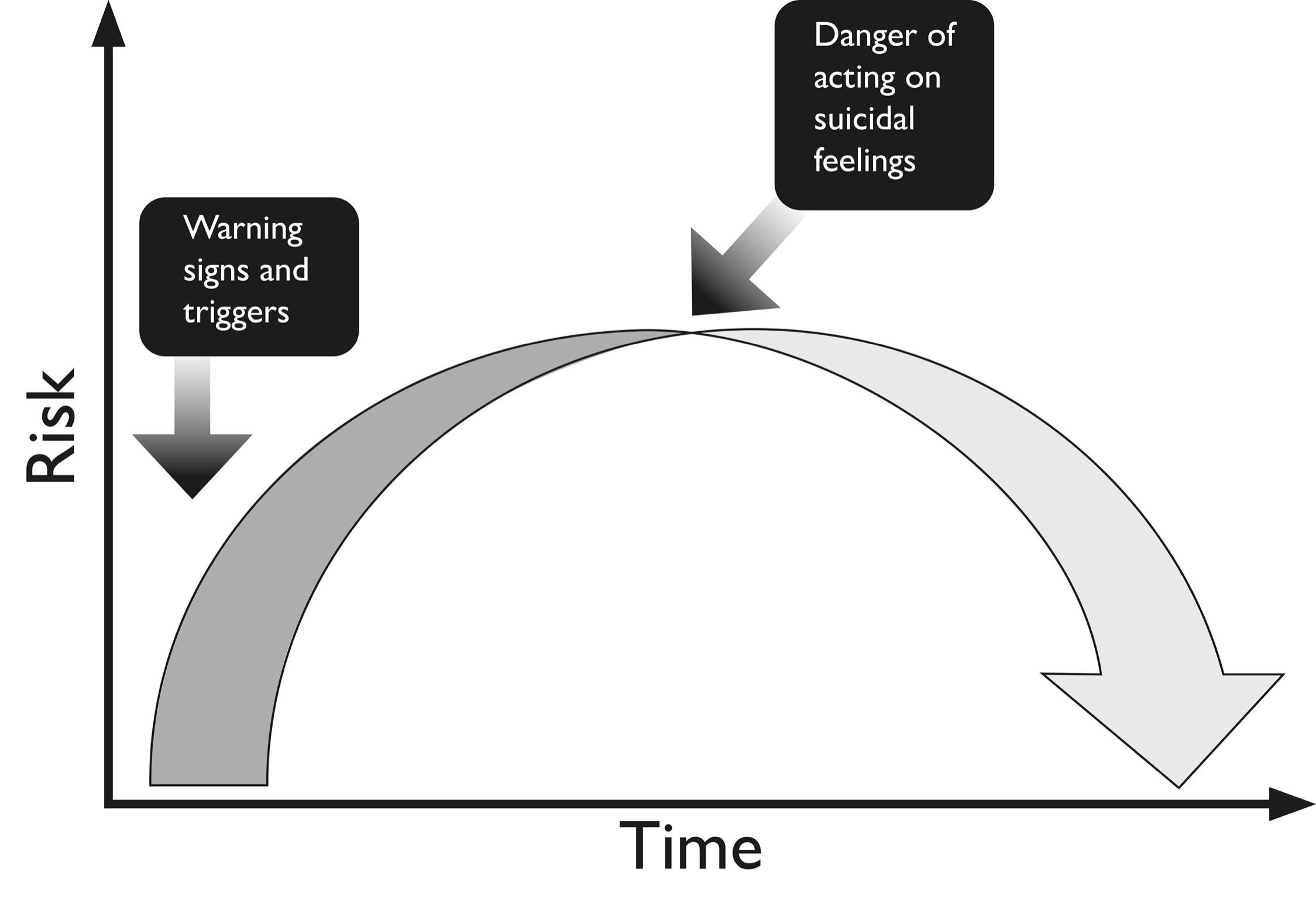

Stanley had Joss’s full attention as she drew a simple axis graph in her notebook. She labeled the horizontal axis Time and the vertical axis Risk. She drew a line shaped like a hill. It began at the bottom left, went upward, then curved back down again on the right.

Stanley said, “This is the suicidal risk curve. We want to try to get you off this curve before you get to the top.” Stanley tapped her pen at the top of the hill. “But the other part that is really important to notice is time. You are not having suicidal thoughts now, right?”

Joss shook his head. “Absolutely not.”

Stanley tapped the lowest part of the hill on the right. “That shows that suicidal thoughts do come down and it’s really important for you to remember that fact. Even without the safety plan, the passage of time enables you to become less suicidal. Nobody stays suicidal forever. And if you don’t act on your suicidal feelings, they eventually come down no matter what.”

Joss looked relieved. “Okay.”

“The passage of time is your friend. And I’m not as interested in what your boss said as I am about how it made you feel. How did you feel when he told you he might have to let you go?”

Joss thought about it. “Helpless. I hadn’t known my sales numbers were so bad. I didn’t know that I was that far behind and I felt helpless about how to get the numbers back up.”

Stanley drew a line near the start of the curve and wrote Helplessness. She said, “I don’t want to put words in your mouth but I’d say feeling helplessness is one of your warning signs. Later you said you felt a tightness in your chest and you felt numb, right?”

Joss nodded.

Stanley drew another line above the first and wrote. Numbness in chest.

“Then you said something very striking that you felt right before you took the pills. Remember?”

“Everyone would be better off without me.”

“Exactly.” Stanley wrote that down at the highest point of the curve, the top of the hill. “And that to me is like, wow, you’re very close to doing something to hurt yourself.”

Stanley reiterated an important point about warning signs. They may begin with an emotional event, such as Joss’s talk with his boss or an argument with a spouse. But what’s important is the person’s internal reaction to that event.

Stanley’s position is consistent with what Drs. Mann and Joiner assert about the internal state of people who attempt to kill themselves. Events in life might objectively be bad, but in the internal life of persons in crises those events feel much, much worse. Academia has a phrase for it—the “diathesis-stress” model of psychological disorders. Diathesis comes from the Greek word for “disposition.” The model holds that everyone has a certain amount of natural disposition for developing a disorder, such as thoughts of suicide. Some have a greater disposition than others, and these are the people whose feelings are more intense and who tend to kill themselves. Stress triggers, such as a fight with a spouse or a threat from a boss, can make their inclination grow.

And therein lies an insight into one of the major Whys of suicide. When someone we care for takes their life, we’re saddled with a lifetime of Whys. Why did they do it? This answer is painfully simple; we cannot really know what someone else is feeling, especially someone in suicidal crisis. To quote Dr. John Mann, “It’s because what you see is not what they see.” We cannot know this major Why.

Fortunately, the safety plan can stop a suicidal urge in its tracks.

Dr. Stanley had Joss write his warning signs on the safety plan template. Having the patient fill in the plan increases his or her buy-in to the intervention and the likelihood they’ll follow it.

And it’s important to note that the safety plan is designed to be completed with a mental health professional who is competent in the intervention. Their training ensures that the rationale for the plan is thoroughly explained, then collaboratively filled out with the patient to identify the most helpful and feasible strategies, with no omissions or shortcuts. People who are given a blank safety plan and told to fill it out on their own often don’t, and if they do, they’re not always likely to follow it. Completing a safety plan with a loved one is not optimal but it’s better than winging it on your own. That said, some particularly disciplined people have been known to download the safety plan from the internet, where it is easily found, fill it out, and work it to a T on their own.

If Joss experienced any of the warning signs, he would grab the completed safety plan and follow it by proceeding to step 2—internal coping strategies. Stanley told me, “We have them identify the things that they can do just by themselves because a lot of the times people get suicidal at night when they are alone. Something that will engross them even for a little while from their suicidal thoughts. Really simple things—this is not rocket science.” Stanley suggest playing with your dog or watching favorite programs on television. “Like The Simpsons for example,” she said. “Comedies are good. Have them record their favorite comedies in advance so they don’t have to go searching for these things when they’re suicidal.” Video games can be good, but long, dense books—probably not. Dostoevsky, for example, isn’t guaranteed to make you feel better. And music. “If they want to listen to music, we work with them to identify what kind of music is certain to not make them feel worse and, hopefully, makes them feel better.”

Ron Joss volunteered that he liked to run. “You know, usually when I’m running, I’ll put on a podcast and no matter what’s going on, I’m kind of in a zone.”

“Okay,” said Stanley, “but we’ll put a couple of cautions on that. One, pick what you’re going to listen to very carefully because we want to make sure it’s not something that’s going to make you feel worse. And second, it’s fine to put down running with your headphones on, but you’re not gonna do that in the middle of the night should you get suicidal.”

“No.”

Stanley helped Joss think of another activity to keep his mind occupied, then they moved on.

“Okay,” said Stanley. “So now we have three distracting activities that you can do on your own without contacting anybody else. These activities may help you not become suicidal. They may just take you right down. And so you put the safety plan away and you go on with whatever you are doing. If it doesn’t work, then you go on to the next step.”

Step 3 is writing down people and social settings that provide distractions. Stanley issued more cautions. Call people you should speak with, such as old friends and relatives. Don’t call your ex-wife and inflame your feelings. Don’t phone your boss and give him a piece of your mind. Included here are visits to social settings such as a friend’s house or a park or a gym but probably not a bar, for obvious reasons. Find places where you feel at home and engaged and, most of all, distracted. Interestingly, with these people and places, you don’t talk about your suicidal feelings. As Stanley says, “Sometimes people have a hard time telling other people that they are feeling bad or that they’re feeling suicidal. But social support and social engagement are really helpful at taking a person outside themselves. So, at this stage, you’re just seeking interaction.”

So far the safety plan has relied on self-help measures, but now it shifts gears. If the suicidal crisis has still not passed, the plan starts pulling out all the stops. In step 4, you ask for help from family and friends who you think would be helpful to you. Stanley told Joss, “The next step is people who you could turn to and say, ‘I’m in trouble. I’m having a crisis.’ Or, hopefully, you could say, ‘I’m feeling suicidal.’ ” Joss was instructed to come up with three people closest to him. And he will have to tell them they are in his safety plan. That is so they won’t be unprepared should he call. And that means telling them he’s made a suicide attempt. That’s a big step.

Stanley shared the tough news. “That would mean having a conversation with that person and letting them know what’s been going on underneath and whether you could rely on them. And often the people you would use as distractions are not gonna be good for telling them you’re in a crisis.”

Going over these steps is not for the squeamish, but patients understand their lives may hang in the balance. The temporary discomfort is worth it.

Now, at this point, despite your best efforts with all the earlier steps, your crisis may still threaten your life. Step 5 is where you talk to a professional, a therapist, a pastor or other spiritual adviser, or call or text the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 for confidential, free crisis support. Step 5 may lead you to an emergency department or a psychiatric hospital, but if that’s the advice of professionals, that’s where you need to be. In this step and others it’s important to write down relevant phone numbers because a person in a suicidal crisis should not face additional complications such as locating telephone numbers.

The importance of the last step of the safety plan cannot be overstated. By now we know that ridding the environment of deadly means of suicide is vital in the treatment of a person in crisis. Step 6 is called making the environment safe.

Stanley said, “What we mean by that is how do we put time and space between the suicidal person and the means they would use to kill themselves? It’s with the same idea of why we use the safety plan to begin with.

“On the risk curve, suicidal urges don’t last forever—they’re relatively short lived. This is why it is very, very problematic if there is a suicidal person in the home and there are loaded guns around the house. We know that more than ninety percent of people who use a firearm in a suicide attempt die. So, they are extraordinarily lethal and often readily available. This is very difficult especially with firearms because people are very attached to their guns and they don’t want to give them up.”

Locking up guns and ammo separately is generally not optimal because the person in crisis may have the combination to the gun safe or keys to gun locks and may be tempted to use them if another suicidal crisis occurs. It’s better to temporarily store firearms with a friend or with a local police department. Patient Ron Joss volunteered that he’s a member of a gun club that will store firearms for members. He owns a rifle; he agreed to take it in. Stanley will contact him after he leaves the hospital to check on whether the firearm is safely stored.

Stanley told me, “Another big one is pills. A lot of people have lots of extra medications lying around the house. We talk with them about disposing of those medications. If somebody is on a psychotropic medication like an antidepressant or an antipsychotic medication, we talk with them about limiting the number of pills they have in their possession at any one point in time. But that often means having a trusted person in their life with whom they feel comfortable saying, ‘I have a month’s worth of medication; I’m gonna keep a week’s worth; can you hold the other three weeks for me?’ ”

Over-the-counter pain and cold medications should not be overlooked. In sufficient quantities, medicines containing ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and aspirin can kill you. Advil and Tylenol are trade names for ibuprofen and acetaminophen, respectively. Some cough and cold medicines can cause extreme harm too.

Stanley said, “That’s another good reason to have a clinician help a patient fill out the safety plan. The clinician has a lot of experience with trying to figure out in a creative and respectful manner the ways that we can limit the patient’s access to medicines for a relatively short period of time.”

At the bottom of the safety plan is a later addition that is perhaps its most potent step. It’s a kind of safety net hanging beneath the whole strategy. It asks about reasons for living that are important.

Back in the conference room, Stanley asked Joss, “So what is that for you when you think about it?”

Joss answered, “My kids. Jack and Sarah. They just moved out of state with their mom, but I talk to them a lot.”

“So it sounds like they’re very special to you. Very important. Okay. So why don’t you write them down?”

Of course many people don’t have children, but many people have beloved brothers and sisters and other relatives and friends who’d grievously suffer should they die. Some have pets that are dependent upon them. Others have lifetime goals they have not yet achieved, or a spiritual faith that is the one thing they live for. There are many good reasons to stay alive.

In the big picture the safety plan does not substitute for prompt, ongoing therapy following a suicidal crisis. But it has been proven to be a durable stopgap and even a kind of therapy on its own to be used until alternatives are available. Patients have dubbed its list of things to do “working the plan,” after the Alcoholics Anonymous saying “working the program.” One military veteran told Stanley, “This is really helpful to me because I’ve had many suicidal crises where I feel like I just had to white-knuckle it through. Like, just hang on ’til the crisis passed. And now I have something to do instead.” Many thousands of individuals share this sentiment.

Stanley said, “The whole idea behind the safety plan is that we want people to learn how to cope on their own as much as possible. Of course, we want them to reach out when they need to reach out, we have people on their plan they reach out to, but it’s on their own initiative.”

Joss would take his safety plan with him as his appointment with Dr. Stanley came to a close. But as a final measure, Stanley had him take a photo of the plan to keep on his smartphone so it’s never far away.

What happens to Ron Joss, then? The safety plan is what’s known as a “stabilization plan.” It is meant to prevent another suicide attempt, but it doesn’t address psychological disorders or risk factors that led to his attempt in the first place. In a perfect world, Joss would quickly begin therapy through his employee health benefits plan. His hospital would follow up with messages of interest and care, which are proven to reduce suicide attempts. Or, if he isn’t covered by insurance or doesn’t have the means, he might get himself to a CCBHC, if one is close by.

Joss might benefit from talk therapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT). According to research, CBT is typically the more successful treatment for conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, phobias, depression, and anxiety. DBT is frequently the best option for treating borderline personality disorder and self-harming behaviors. Both therapies are effective in reducing suicide attempts. Until therapy begins, Joss can ward off additional attempts by “working the plan.”

Many studies have tried to determine which interventions are most successful against suicide. Therapists have created versions of both CBT and DBT that are customized to address suicidal behavior. And there are other stabilization plans and therapy types as well. A quick method called the Crisis Response Plan (CRP) is a calming technique developed by a suicidal person in collaboration with a trained clinician. It’s often handwritten on an index card for easy access. Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) builds a therapeutic alliance with suicidal patients from a place of empathy.

Some interventions are good at stopping suicide attempts but don’t reduce suicidal ideation. If you treat people who attempt suicide, you may fail to address the causes of their underlying ideas and thoughts about killing themselves. But if you could treat sufferers of ideation, you’d generally get fewer downstream suicide attempts.

Each year in the United States some 15 million people suffer from suicidal ideation—persistent, agonizing thoughts about killing themselves. About 1.2 million of them attempt suicide. About 47,000 of those individuals end their lives. What moves those who suffer from suicidal ideation to go further and make a suicide attempt? As Thomas Joiner observes, the capability for suicide is what separates the thought from the act. And that capability can be learned. Far better to start upstream and attack ideation before suicide’s progression goes any further.

In a classroom a youthful middle-aged man with styled white hair said, “With patients I’m really transparent and I’ll say things like of course you can kill yourself. But is that the best thing to do? Since you’re here with me and I’m a licensed therapist, I’m thinking a part of you is not quite prepared to terminate your biological existence. And if that’s true, then we should consider what we can do together to make your life more worth living. You have everything to gain and nothing to lose. And the fact of the matter is, you can always kill yourself later.”

You can always kill yourself later. That floored me. Even though he said it in a matter-of-fact way, the statement seemed at odds with the warm, optimistic demeanor of David Jobes. But the Catholic University of America professor was making a point about the therapy he created, CAMS. At thirty-five years old, CAMS is a relative newcomer in the therapeutic world, but its ability to reduce suicidal ideation is backed by randomized controlled trials and the enthusiasm of some thirty thousand clinicians around the world who have been trained in CAMS. I encountered CAMS in use everywhere from Charlotte, North Carolina, to Copenhagen, Denmark. It has achieved success because it reduces symptoms of depression and hopelessness and suicidal ideation in six to eight sessions. When you consider that some suicidal patients have been hospitalized for years on end and some undergo CBT and DBT also for years, CAMS is a breakthrough.

The point Jobes was making was about CAMS’s radical honesty. Honesty is perhaps the most important of the therapy’s four guiding principles, or “pillars,” as Jobes calls them. The point of honesty is to pull down the wall separating therapist and patient, to put all your cards on the table. In most places by law, if a therapist thinks you’re an imminent danger to yourself, they can put you in a hospital. Jobes puts that card on the table. You are a free individual with your own volition—you can go kill yourself if you want. That card goes on the table. Radical honesty helps neutralize the traditional power dynamic between patient and therapist, in which the therapist has all the power—including the ability to have you committed to a psychiatric hospital—and the patient has none, except to take their own life. In Jobes’s experience, dispensing with the power dynamic strengthens the therapeutic alliance needed for treatment.

And honesty helps patients keep their sense of autonomy. Someone willing to tell you “You can always kill yourself later” is more invested in your free will than someone threatening to put you in a hospital. And one of the carrots Jobes dangles is that with CAMS you don’t have to go to a hospital at all. With CAMS the emergency-department-therapy-session-referral pipeline doesn’t exist. You go straight from suicidal incident to evaluation and CAMS. No hospital and usually no medicines. What have you got to lose? You can always kill yourself later.

Jobes told me, “From a clinical standpoint, we wanna hit the pause button and say, ‘Before you kill yourself forever, have you turned over every stone? Can we help you do that to see if there’s a way to make this life livable?’ And I think that’s a compelling argument since we’re talking about forever. We all get to be dead soon enough, what is the hurry?”

In tens of thousands of rooms all across America, therapists and patients talk about forever. We are familiar with the traditional couch and chair, the two facing chairs, the two chairs with a table between—variations on the static geography of most therapy rooms. Butts planted, nobody moves. But as I witnessed a CAMS therapy session with an undergraduate student, Maggie, it wasn’t static. There were three chairs in the room, one for Maggie, one for Jobes, and an empty chair beside Maggie. Maggie was a student in her early twenties, a brunette athlete whose face reflected abject pain.

The session began much like the safety plan, with Jobes gaining a baseline understanding of Maggie’s situation in her own words. In brief, Maggie’s boyfriend, Tyler, suddenly died of an undiagnosed heart ailment. Both were on the university swim team and had many friends in common. Upon her boyfriend’s death, Maggie sank into depression. Her roommates were cruelly unsympathetic.

“Nobody really wanted to be around me because I was so sad. My roommates kicked me out. They said they didn’t want to room with me because I was too much to handle, so I got moved to another room. And this whole time I’ve been so alone in this grieving process.”

One night, Maggie set a timer for ten minutes and texted her team group chat. “Somebody help,” she said. She decided that if nobody came within ten minutes, she would swallow medication she’d been prescribed for depression. Fortunately, two women showed up to talk. She was referred to the counseling center and given an appointment with Dr. Jobes.

Jobes expressed heartfelt sympathy and concern, then introduced CAMS by saying, “I suspect there are things on your mind that we can address together. I’ve found that going through a written assessment together can help us understand the nature of those things. It’s a tool that I’ve used many times and it kinda helps me understand what you’re going through.”

“Okay.”

“And we fill it out together, if that’s okay.”

“All right.”

“And to do it, I could take a seat next to you if you don’t mind.”

Then it happened. The action. With Maggie’s assent, Jobes rose and took the seat next to her, bringing along his clipboard and papers. It was like a chess move. Now they were close together but not too close. This therapy jujitsu accomplishes a couple of things. Like Stanley and Brown’s safety plan, it pulls back the curtain on what the therapist is writing and thinking about, because therapist and patient fill out the document, called the CAMS Suicide Status Form, side by side. No secrets, and that reinforces buy-in and collaboration. Second, it promotes another one of CAMS’s primary principles—empathy. Empathy doesn’t mean as much coming from the other side of the room. Empathy needs proximity.

Jobes told me, “We used to have a different approach. At school in the eighties and nineties, the bulk of inpatient psychiatry was like, Have you thought about suicide? Yes I have. You can’t kill yourself. Oh yeah? It’s my life, I can do what I want. No you can’t! Yes I can. Wanna bet?”

Boom, off to the psychiatric hospital.

“And that’s the dynamic we’re trying to avoid,” said Jobes. “Because one of our pillars is empathy. But when you think of empathy with people who are suicidal, there are some issues around it. Why would it be difficult for clinicians to be empathic of suicidal risk?”

First, therapists are afraid they might lose a patient who, despite therapy, kills themselves. Jobes has lost patients. Many therapists have lost patients. It’s devastating. Therapists either shoulder the risk of attaching to somebody and possibly having them take their life, or they keep a “professional” distance and neglect empathy.

And second, lawsuits. “There’s a tremendous fear of malpractice,” said Jobes. “And for some clinicians it’s just paralyzing. Because they’re afraid if they lose a patient, the family is going to sue them. So even though the patient is not extremely suicidal, it’s better to put them in the hospital. Better safe than sorry. Have your rear end covered, so to speak, right?”

But with rear ends covered, empathy will have flown, and with it honesty and the kind of alliance Jobes and Maggie are beginning to forge. Three pillars come into play now, with honesty and empathy supporting collaboration.

Maggie fills in the CAMS Suicide Status Form and together she and Jobes build a baseline for her condition. On a scale of 1 to 5 they rate feelings like psychological pain, agitation, and stress, and indicate the source of those feelings. For example, Maggie’s psychological pain is a 5—the worst—and its source is “not being able to talk to Tyler,” her deceased boyfriend. She rates her agitation level as a 5 too. She writes the source of this stress is when she’s in the pool because it reminds her of Tyler.

Next the plan addresses Maggie’s reasons for wanting to live. But unlike the safety plan, CAMS also takes onboard her reasons for wanting to die. In order of importance, Maggie’s reasons for living are to honor Tyler’s memory, to graduate from university, and to get a dog. For dying, Maggie cites that she’s alone now, she cannot have fun, and she feels useless. Then, alarmingly, she rates her desire to live a 2 out of 8. Not very high. But she rates wanting to die as a 2 also, which is at least better than a 3 out of 8.

Jobes learns Maggie’s suicidal ideation appears as soon as she wakes up in the morning. She remembers Tyler is gone and she wants to die. This rumination lasts for two or more hours. She’s thought about how she might kill herself. She’s a frequent metro train rider. There’s a station on campus.

Maggie says, “I think if I really wanted to go through with it, I could just jump in front of the metro.” One night she thought about going to the metro station, but she learned it was closed.

It all goes down on the form in Maggie’s hand, along with more of what we recognize as risk factors and warning signs. Maggie’s been drinking alone, she’s sleeping poorly, she feels like a burden, and she’s suffered two significant losses. Tyler of course, but also her lifetime joy, swimming. And her friends have abandoned her.

In Thomas Joiner’s interpersonal theory of suicide she’s got both feet firmly planted in Thwarted Belongingness (Loneliness) and Perceived Burdensomeness. Does Maggie have the Capability to kill herself as well?

From an observer’s perspective, Maggie is lost deep in the woods. The CAMS Suicide Status Form breaks down her suicidal ideas into precise, painful parts. In total so far, they are alarming, almost like a psychological autopsy of a suicide that’s already occurred. And you can understand why some therapists might get her to a hospital pronto. Not Jobes. In his view, hospital treatment would not save her from suicide and CAMS is focused on suicide, as he put it, “like a dog with a bone.”

In fact, the laser focus on suicide means there’s much that therapist and patient will not talk about if it is not connected to suicide. No one’s going to ask about your relationship with your parents. Your birth order among your siblings isn’t very important here either.

Jobes says, “We’re not going to talk about a whole lot of other things while you’re engaged in this intervention because we’re trying to take suicide off the table. Now, here’s the thing, for some people that’s good news. You know like ‘Phew, I really don’t want to have these feelings anymore. I can’t go to sleep at night.’ For other people it’s kind of like, ‘Uh, this is my thing. This is actually a way that kind of keeps me alive. This is sort of like my warm blanket and you’re trying to take it away from me.’ ”

Is this Maggie? No, while she has evaluated her own risk for suicide as a 3 out of 5—bad news—she’s also told Jobes that her suicidal ideas frighten her. They don’t bring her comfort. And Jobes indicates on the form that in his view Maggie is not in imminent danger of suicide.

On the other hand, he understands those who find suicide comforting. For them, it represents the promise of relief from the pain of depression and suicidal thoughts. In a 2014 study of 217 patients with a history of recurrent depression and suicidality, 15 percent reported feelings of comfort from thoughts of suicide. CAMS may not be the answer for these patients or for the chronically suicidal. And it may not be as effective as more traditional approaches to deeply entrenched conditions. “So this addresses the idea that if you’ve got a hammer, all the world’s a nail,” Jobes says. “CAMS isn’t always the best therapy. What we really need are different tools for different kinds of needs.”

CAMS brings a large toolbox to its treatment plan that may include elements of behavioral therapies. Its forte is bringing the tools to bear on someone who’s having their first or second phase of persistent thoughts about suicide, and who finds that ideation disturbing. Like Maggie.

Contained within the CAMS Suicide Status Form is a stabilization plan that covers now familiar ground. Maggie agrees to remove lethal means from her room, which means giving her medication to a friend and having the friend dispense one pill at a time. It also means avoiding the metro, going on the metro with a companion, or taking a taxi. It means getting rid of ropes and knives.

Jobes tells her, “The thing about lethal means is that when they’re available, they’re a temptation. And this intervention is designed to save your life. But to save your life, we’ve got to keep you alive and not have you tempted by other means.”

Maggie thinks up coping activities, things to keep her mind off suicide, including watching a movie, working out in the gym, journaling, and listening to music. She writes down people she can contact to decrease her isolation as well as the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, which she can call or text anytime for confidential, free crisis support. Jobes gives her his personal cell number in case of an emergency.

Maggie plans to stay away from the pool for the foreseeable future because of its painful associations.

The collaborators have one more task to complete—a treatment plan. Jobes proposes six sessions. “Most people respond to this intervention by six sessions. And that may seem crazy, but that’s what the research shows.” Jobes then asks Maggie to identify two problems that have the most potential to her for self-harm. He calls them drivers. “These are the things that made suicide become an option for you.”

Being alone has come up repeatedly as a source of agitation and suicidal ideation. Jobes says, “There’s a number of things that we can do to attack this particular issue. We want to decrease your isolation and increase your social support. We’re going to do something called behavioral activation, which is a part of cognitive behavioral therapy. Behavioral activation helps us understand how behaviors impact emotions.”

The second big driver is Tyler being gone. For that, Jobes prescribes grief therapy. Maggie needs to grieve her loss. “I’d like to learn more about Tyler,” says Jobes.

Maggie nods her assent.

“And about your relationship. And there’s some bibliotherapy for grief too. I’ll prepare some readings for you.”

Maggie looks a little wiped out. Jobes says so far what has only been implied. Her stabilization plan will help keep bad thoughts at bay until their next session. And with each session as they address her feelings, her overall ratings of risk should go down. As treatment of her drivers evolves, overall distress will decrease along with her suicidal ideation. Toward the end of CAMS she can look forward to meaningfully reduced suicidal ideation, an increased sense of hope, and a gradual reconsideration of a life worth living.

Maggie smiles hopefully. “That would be nice.”

Jobes says, “Most people do get better with this intervention. It’s very focused on suicide but it’s also focused on what’s on your mind. We’re going to see what fits and tailor your treatment as we go. Every session, we’ll update the treatment plan to make sure we’re getting at the drivers that put your life in peril.”

It’s been a productive albeit emotional meeting of the minds over the sources of Maggie’s crisis. A majority of CAMS patients report that they enjoy the therapy. In a final collaborative act, Maggie and Jobes sign and date the CAMS Treatment Plan, along with copies that patients take from every session.

Jobes notes, “CAMS does not eradicate every vestige of suicidal thoughts and feelings; instead, it helps patients better manage such thoughts and feelings while becoming more behaviorally stable. The single biggest effect of CAMS from clinical trials is that it increases hope and decreases hopelessness, and to me that is the secret sauce of lifesaving work!”

STANLEY & BROWN SAFETY PLAN

Step 1: warning signs:

Step 2: Internal coping strategies—things I can do to take my mind off my problems without contacting another person:

Step 3: People and social settings that provide distraction:

-

Name

Phone

-

Name

Phone

-

Place

-

Place

Step 4: People whom I can ask for help during a crisis:

-

Name

Phone

-

Name

Phone

-

Name

Phone

-

Name

Phone

Step 5: professionals or agencies I can contact during a crisis:

-

Clinician/Agency Name

Phone

Clinician Pager or Emergency Contact #

-

Clinician/Agency Name

Phone

Clinician Pager or Emergency Contact #

-

Local Emergency Department

Emergency Department Address

Emergency Department Phone

-

Suicide Prevention Lifeline Phone: 988

Step 6: Making the environment safe (plan for lethal means safety):

Step 7: List the reasons for living that are most important:

The Stanley-Brown Safety Plan is copyrighted by Barbara Stanley, PhD, and Gregory K. Brown, PhD (2008, 2022). Permission to use and additional resources are available from www.suicidesafetyplan.com