An unfinished copy?1

The last piece in The Art of Fugue is the one marked in the Original Edition as Fuga a 3 Soggetti.

Was that also Bach’s last composition? Furthermore, was the whole cycle, called The Art of Fugue, Bach’s last composition? The person whose acquaintance with the subject matter was considered totally reliable did answer this question. Johann Sebastian Bach’s obituary was written by Carl Philipp Emanuel and Johann Friedrich Agricola.2 In this document, which includes one of Bach’s earliest biographies, it is unambiguously stated: ‘Die Kunst der Fuge. Diese ist das letzte Werk des Verfassers …’.3

Nevertheless, and despite the credibility of this source, the information issued in the obituary was decisively rejected by scholars in the 1980s and 1990s. At the musicological conference dedicated to Bach’s 300th anniversary (Leipzig, 1985), Yoshitake Kobayashi presented results of a handwriting analysis in Bach’s manuscripts from the composer’s last years. The data of Kobayashi’s analysis led to major revisions in the dating of many of Bach’s compositions, including The Art of Fugue. Particularly dramatic was the scholar’s conclusion that ‘Nunmehr ist nicht die Kunst der Fuge, sondern die h-Moll-Messe als Bachs Opus ultimum anzusehen’.4 Kobayashi repeated this statement in his major study,5 for which he used diplomatics.6

Kobayashi’s results looked so convincing that in the following (1990) international Bachakademie summer meeting in Stuttgart, a book calling the Mass in B minor Bach’s ‘Opus ultimum’, was issued.7 The book’s title implies a universal acceptance of the status of the Mass in B minor as Bach’s last opus. This was, indeed, the general impression: a year after Kobayashi’s publication, Christoph Wolff declared that ‘we must take leave of the time-honored idea that The Art of Fugue was Bach’s “swan song”’.8 Yet, there are substantial reasons, grounded in Bach’s manuscripts and various other documents, to doubt this premise.

Documents

The most important source is the preserved handwritten fragment of the quadruple fugue. To clarify, however, what the fugue was as a whole, it is essential to understand its structure and position within the entire cycle and to juxtapose its autograph with available documents that reflect the publication process of The Art of Fugue. Several sources, beyond the musical materials, are needed for this undertaking. Listed in chronological order, these are:

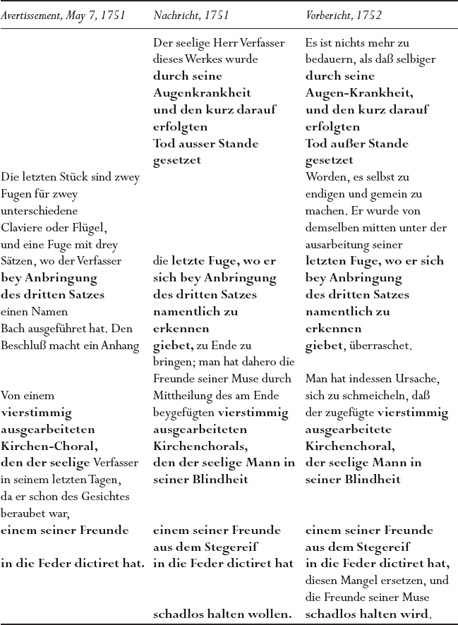

• Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s advertisement of subscriptions for The Art of Fugue in the Critische Nachrichten aus dem Reiche der Gelehrsamkeit, published in Berlin, on May 7, 17519

• C.P.E. Bach’s notice (‘Nachricht’) on the verso of the title page in the Original Edition, offered for sale on September 29, 1751 (Figure 18.1)10

• Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg’s preface (‘Vorbericht’) to the second edition of The Art of Fugue (written probably in February or March 1752; the edition was offered for sale on April 2, 1752)

• Philipp Emanuel and Johann Agricola’s description in the obituary of the ‘unfinished’ fugue’s peculiarities (published in 1754)11

• C.P.E. Bach’s NB on the last page of the ‘unfinished’ fugue’s autograph (written after 1780)

Excerpts from these documents, related to the completion of the ‘last’ fugue and of The Art of Fugue in general are compiled here following their chronological order:

• From Carl Philipp Emanuel’s advertisement (Berlin, May 7, 1751):

Es ist aber dennoch alles zu gleicher Zeit zum Gebrauch des Claviers und der Orgel ausdrücklich eingerichtet. Die letzten Stück sind zwey Fugen für zwey unterschiedene Claviere oder Flügel, und eine Fuge mit drey Sätzen, wo der Verfasser bey Anbringung des dritten Satzes einen Namen Bach ausgeführet hat. Den Beschluß macht ein Anhang von einem vierstimmig ausgearbeiteten Kirchen-Choral, den der seelige Verfasser in seinem letzten Tagen, da er schon des Gesichtes beraubet war, einem seiner Freunde in die Feder dictiret hat.

[Nevertheless, everything has at the same time been arranged for use at the harpsichord or organ. The last pieces are two fugues for two keyboard instruments and a fugue with three themes, in which the author, writing the third theme, has displayed his name Bach. The conclusion is made with an appendix of a four-part church hymn, which the late author, during his last days, already deprived of his eyesight, dictated to the pen of a friend.]12

• From Carl Philipp Emanuel’s notice on the verso of the Original Edition’s title page:

Der selige Herr Verfasser dieses Werkes wurde durch seine Augenkrankheit und den kurz darauf erfolgten Tod ausser Stande gesetzet, die letzte Fuge, wo er sich bey Anbringung des dritten Satzes namentlich zu erkennen giebet, zu ende zu bringen; man hat dahero die Freunde seiner Muse durch Mittheilung des am Ende beygefügten vierstimmig ausgearbeiteten Kirchenchorals, den der selige Mann in seiner Blindheit einem seiner Freunde aus dem Stegereif in die Feder dictiret hat, schadlos halten wollen.

[The late author of this work was prevented by his disease of the eyes, and by his death, which followed shortly upon it, from bringing the last fugue, in which at the entrance of the third subject he mentions himself by name [through the notes BACH, that is, B -A-C-B

-A-C-B ], to conclusion; accordingly it was wished to compensate the friends of his muse by including the four-part church chorale added at the end, which the deceased man in his blindness dictated on the spur of the moment to the pen of a friend.]13

], to conclusion; accordingly it was wished to compensate the friends of his muse by including the four-part church chorale added at the end, which the deceased man in his blindness dictated on the spur of the moment to the pen of a friend.]13

• From Marpurg’s preface to the second Original Edition (1752):

Es ist nichts mehr zu bedauern, als daß selbiger durch seine Augen-Krankheit, und den kurz darauf erfolgten Tod außer Stande gesetzet worden, es selbst zu endigen und gemein zu machen. Er wurde von demselben mitten unter der Ausarbeitung seiner letzten Fuge, wo er sich bey Anbringung des dritten Satzes nahmentlich zu erkennen giebet, überraschet. Man hat indessen Ursache, sich zu schmeicheln, daß der zugefügte vierstimmig ausgearbeitete Kirchenchoral, der seelige Mann in seiner Blindheit einem seiner Freunde aus dem Stegereif in die Feder dictiret hat, diesen Mangel ersetzen, und die Freunde seiner Muse schadlos halten wird.

[Nothing could be more regrettable than that, through his eye disease, and his death shortly thereafter, he was prevented from finishing and publishing the work himself. His illness surprised him in the midst of the working out of the last fugue, in which, with the introduction of the third subject, he identifies himself by name. But we are proud to think that the four-voiced chorale fantasy added here, which the deceased in his blindness dictated ex tempore to one of his friends, will make up for this lack, and compensate the friends of his Muse.]14

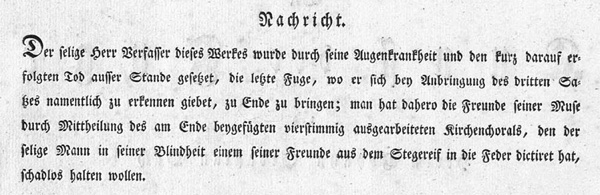

• From C.P.E. Bach and Agricola’s obituary, published in 1754 (Figure 18.2):

Die Kunst der Fuge. Diese ist das letzte Werk des Verfassers, welches alle Arten der Contrapuncte und Canonen, über einen eintzigen Hauptsatz enthält. Seine letzte Kranckheit, hat ihn verhindert, seinem Entwurfe nach, die vorletzte Fuge völlig zu Ende zu bringen, und die letzte, welche 4 Themata enthalten, und nachgehends in allen 4 Stimmen Note für Note umgekehret werden sollte, auszuarbeiten. Dieses Werk ist erst nach des seeligen Verfassers Tode ans Licht getreten.

[The Art of the [sic] Fugue. This is the last work of the author, which contains all sorts of counterpoints and canons, on a single principal subject. His last illness prevented him from completing his project of bringing the next-to-the-last fugue to completion and working out the last one, which was to contain four themes and to have been afterward inverted note for note in all four voices. This work saw the light of day only after the death of the late author.]15

• Carl Philipp Emanuel’s note (written after 1780) on the last page of P 200/1–3 (the ‘unfinished’ fugue):

NB. Ueber dieser Fuge, wo der Name BACH im Contrasubject angebracht worden, ist der Verfasser gestorben.

[NB. While working on this fugue, in which the Name BACH appears in the countersubject, the author died.]16

Even a superficial glance at these documents reveals some remarkable similarities among the three first documents. There is general agreement that the first two documents (the advertisement of the subscription and the preface to the 1751 edition) could have been written only by Emanuel.17 The text of the third document (Vorbericht, 1752), although written by Marpurg, considerably depends on the first two (see Table 18.1, text in bold letters). Finally, the last two documents, too, are traced back to Emanuel.

Thus, although Marpurg is named the author of the 1752 preface and Johann Friedrich Agricola, J.S. Bach’s student, might have contributed to the obituary, all five sources lead back to the same person—Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. If this is correct, there should be no contradictions between the documents concerning the conclusion of the whole cycle in general, particularly concerning the last fugue.

Nevertheless, there are significant—and quite essential—incongruities between the documents, reflecting the changes in C.P.E. Bach’s perception of the ways in which The Art of Fugue remained unfinished.

According to the first three documents, Emanuel was initially convinced that only one fugue remained unfinished, the one that should be the last in the cycle. This fugue appears in the Original Edition as the unfinished Fuga a 3 Soggetti, the fugue on three themes, the last of which was the B-A-C-H theme.

However, the excerpt from the obituary disagrees not only with perceptions about Bach’s last days, as they are established in Bach studies, but also with other documents that were issued by Emanuel himself.

The text of the obituary implies that it is no later than the beginning of 1754 (more probably even earlier)18 that Emanuel became aware that in fact there were two unfinished fugues: one ‘penultimate’ (‘die vorletzte Fuge’), and another one ‘last’ (‘und die letzte’). The essay specifies that the ‘penultimate’ was the Fuga a 3 Soggetti, while the ‘last’ was another fugue, one that had not been mentioned in previous documents. That last fugue was not on three but on four subjects.

The discrepancy between the 1751 announcement of the subscription and the obituary, published in 1754, shows that something must have changed Emanuel’s perception of the intended content of The Art of Fugue. It is clear that his 1754 view of the work drastically differs from the one presented in his first and second editions, three and two years earlier, respectively.

This new perception of the cycle’s ending could have been changed only by new information which Emanuel must have considered to be fully reliable. Who was his source?

Philipp Emanuel’s informant

The competent informant, whom Emanuel could completely trust, was a person who watched the process of the last fugue’s composition and perhaps even participated in the process in one way or another. Theoretically, it could be any member of the Bach family who was present at the composer’s house when this process took place. The materials related to the last fugue show that one of Bach’s younger sons, Johann Christoph Friedrich, who at that time was 17 and a half years old, was indeed deeply involved in this composition, and traces of his contribution as copyist and corrector are visible in the Autograph. However, he left Leipzig in the very last days of December 1749 for a new position at Bückeburg.

Christoph Friedrich’s close involvement with The Art of Fugue’s composition process schooled him in fugue writing. It is not a coincidence that it was he, of all Bach’s sons, who chose to follow his father’s tradition in the field of fugue up to its highest degree. His own obituary states: ‘Die Fuge war sein Element. Hier zeigte er sich jedesmal in seiner wahren Bachischen Gestalt’.19 Charles Burney wrote that Christoph Friedrich was ‘regarded as the greatest fugist, and most learned professor in Germany’.20

When and how could Christoph Friedrich convey to Philipp Emanuel important information about the concluding fugue (and further, about two closure fugues rather than one)? The only personal contact between Friedrich and Emanuel could take place in Bückeburg, at the end of July 1751, during the Prussian King Frederick II’s visit to bestow upon Wilhelm, the Count of Schaumburg-Lippe-Bückeburg, the Order of the Great Prussian Eagle for military merits.21 Christoph Friedrich left his father’s home, probably shortly after Christmas 1749, to serve as musician in that court. Emanuel was part of the King’s entourage and thus could have met his brother and learn new information, hitherto unavailable to him, about The Art of Fugue. Thus, by the end of July or, at the latest, the beginning of August 1751, C.P.E. Bach could have gained reliable information about the finalising particulars of The Art of Fugue, realising that Friedrich could tell his brother about the last fugue of the cycle only as it stood by the time of his departure from Leipzig to Bückeburg, that is, before January 1750.

This means that the new information about the existence of two closing fugues could have been introduced into the obituary only after the two brothers had met in July 1751. This news, with specific additional features concerning the last fugue, was sent to Mizler for publication in his Musikalische Bibliothek (albeit published only three years later). What did this new communication consist of?

The new information

The style of the paragraph that describes The Art of Fugue in the obituary differs from the rest of that text. It uses contemporary professional terminology, the meaning of which may be missed by the modern reader. The central sentence in this paragraph (quoted above in full, also in Figure 18.2) states:

Seine letzte Kranckheit, hat ihn verhindert, seinem Entwurfe nach, die vorletzte Fuge völlig zu Ende zu bringen, und die letzte, welche 4 Themata enthalten, und nachgehends in allen 4 Stimmen Note für Note umgekehret werden sollte, auszuarbeiten.

[His last illness prevented him from completing his project of bringing the penultimate fugue to completion and working out the last one, which was to contain four themes and afterwards to be inverted note for note in all four voices.]22

This description may seem peculiar or even inarticulate, unless it is seen within the context of eighteenth-century fugue theory and, more specifically, of mirror fugues and their paradoxes.

The paradoxes of mirror fugues

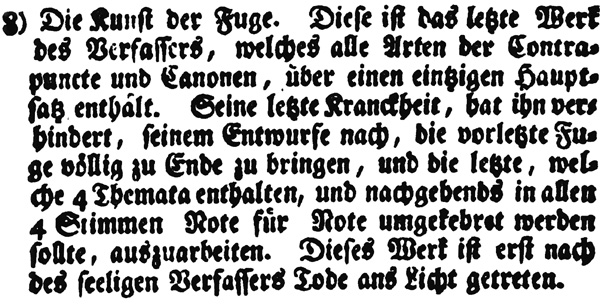

This type of fugue has one curious characteristic. Each mirror fugue is, in fact, two fugues, thus creating what could be perceived as a numerical paradox. The two fugues that make for one mirror fugue are written usually one above the other within one brace, thus highlighting their mutual kinship and exposing how the lower system originates in the top one. The first, Contrapunctus 12, is a four-voice mirror fugue, and Contrapunctus 13 is a three-voice one. Each one of the above is actually two fugues: recta and inversa. The Autograph score of the four-voice fugue presents its components separated by a row of short double strokes (Figure 18.3):

The fugue at the bottom of the braced system, copied in inverse counterpoint, mirrors the top one. The initial combination (written at the top) is the fuga recta and its derivative—the fuga inversa. Hence, while composing the fuga recta, one should keep in mind that its material will be inverted, and once the initial combination is done, the composer has in mind its derivatives, too.23 The remaining task is their realisation: writing them out, which in the musical theory of Bach’s times was termed elaboratio, evolutio, or Ausarbeitung. Clearly, such operation does not require the same intellectual effort that was needed for the creation of the initial combination: the author knows the result ahead of its being written down.

One case, however, deserves special attention, in spite of being seemingly obvious. For a mirror fugue, one should first compose the whole fuga recta, and only afterwards invert all its parts, thus creating its mirror, the fuga inversa.

The paragraph in the obituary about The Art of Fugue is now clearer. Taking into account the paradox of mirror fugues and the terminological specificity of Ausarbeitung, Note für Note, nachgehends, and the like, the description of Bach’s actions, implied in the obituary’s paragraph about The Art of Fugue, becomes transparent.24 Moreover, it is now apparent that the fugue described by Philipp Emanuel was the quadruple mirror fugue; Bach did not finalise the fuga recta, hence he could not elaborate upon (Ausarbeiten) its inversion—the fuga inversa. Bach intended to end The Art of Fugue precisely as it is described in the obituary, with the quadruple mirror fugue. The set of two fugues that Emanuel described as the penultimate and the last are in fact the one mirror fugue that was to conclude of The Art of Fugue.

What are the four subjects?

As Gustav Nottebohm showed already in 1881,25 the answer to this question is quite simple. Since the last piece is a mirror fugue, then both the penultimate and the last fugue (the fuga recta and the fuga inversa) use the same set of four themes. Three are known: they appear in the Original Edition, as the ‘unfinished’ fugue, under the title Fuga a 3 Soggetti.

The fourth theme is not difficult to figure out: the obituary mentions that the whole cycle is composed ‘über einen eintzigen Hauptsatz’ [on a single principal subject] which is precisely the theme missing in the autograph of the ‘unfinished’ fugue. Bach could not have finished the cycle with this fugue without this particular theme.

Nottebohm showed that the three themes on which the Fuga a 3 Soggetti is written indeed combine well with the main theme of the cycle (see Example 18.1). It is hard to imagine that such a combination could exist just by coincidence. When combining contrapuntal materials Bach always strived to achieve a texture in which each theme would be easily identified, clearly heard and not intermingle with the others. In this respect, the high correlation of the main theme of the cycle with each one of the other themes and also of the whole construction in general, is evident.

However, the combination could sound even better if the main theme were presented not in its original form, which includes 12 notes, but in its more elaborate presentation, which consists of 14 notes (Example 18.2):

In such a form, the first motive of the cycle’s main theme (in the alto) creates imitational correspondence with the first theme of the Fuga a 3 Soggetti (in the bass), the latter presenting the first four notes in an augmented imitation. The result of inverting this combination, in the fuga inversa (Example 18.3) sounds no less natural than the one of the fuga recta, strongly suggesting that Bach had already planned it during the composition process. Thus, although not proven beyond doubt, Nottebohm’s hypothesis that Bach planned the simultaneous statement of the four subjects in the last fugue seems quite convincing.

For a long time, the thesis according to which J.S. Bach intended to end the cycle with the fugue on these four themes, implying that the simultaneous combination of the four themes should appear at the end of the ‘Unfinished’ Fuga a 3 Soggetti, remained undisputed. In 2008, however, Gregory Butler challenged this conception, rejecting ideas he formerly supported and offering instead two sensational assertions:26 the first was that Bach had never planned to include the Fuga a 3 Soggetti in The Art of Fugue.27 The second, that Nottebohm’s contrapuntal combination is inadequate. Butler presented several arguments to support these claims:

• Emanuel did not regard this fugue as composed on the cycle’s principal theme, since in his announcement of the subscription to the Original Edition28 this fugue is grouped with the mirror fugue for two claviers and the arrangement of the chorale—pieces that do not belong to the cycle, listing them after his discussion of the fugues that are ‘composed upon one and the same principal theme’ (Butler’s emphasis).

• The autograph paper on which the Fuga a 3 Soggetti is inscribed, its watermarks and handwriting all relate to the very last period of Bach’s life, too late, in Butler’s opinion, for the time in which the composer worked on The Art of Fugue.

• Unlike the rest of the cycle, the Fuga a 3 Soggetti is written in keyboard score.

• ‘The principal subject of the Art of Fugue is uncomfortably close in its formulation to the first subject’ [of the Fuga a 3 Soggetti—A.M.].29

• The main subject’s ‘supposed combination with the three subjects of this fugue is far from convincing, contrapuntally’.30

• Concluding the work with the group of four canons would be more congruent with Bach’s modus operandi.

From the above, Butler infers that ‘despite the fact that there is not a shred of evidence that this work belongs in the collection, and much that argues against this assumption, Bach scholars are unwilling to give it up, and so the myth endures’.31 In lieu of this ‘myth’, he offers his own alternative interpretation:

• The piece under discussion had to be a triple fugue, just as its title indicates: Fuga a 3 Soggetti.

• The Fuga a 3 Soggetti was prepared by Bach for print as his due contribution to the Society of Musical Sciences for the year 1750, and not for The Art of Fugue.

• The autograph of the fugue (P 200/1–3) is a clean engraver copy (Abklatschvorlage).

• The Fuga a 3 Soggetti was completed at that particular time because Bach intended to take advantage of the opportunity, sending it to print together with The Art of Fugue.32

Butler does not explain his claim that the combination of the four themes is ‘far from convincing, contrapuntally.’ In fact, the good combination of the fugue’s three themes with the main theme of the cycle actually suggests that this fugue does belong to The Art of Fugue. The high compatibility of rhythm, melody and harmony in the joint statement of all four themes meets all criteria of normative counterpoint. On the other hand, though, Butler’s argument here relies on two typical mistakes that circulate in Bach studies. The first is that the resemblance between The Art of Fugue’s principal subject and the first subject of the Fuga a 3 Soggetti is ‘uncomfortably close in its formulation’ [my emphasis—A.M.]. This claim, valid only for the 14-note version of the main theme, ignores that the relation between these two parts is a contrapuntally adequate imitation in augmentation (see Example 18.2). This emphasises the themes’ compatibility as well as the innate coherence of the entire combination, an absolutely typical feature of Bach’s compositional style. The second mistake is the claim that Nottebohm’s combinations of the four themes are impossible to perform on a keyboard.33 While Nottebohm’s goal was to show the theme’s contrapuntal compatibility rather than the possibility of performance, it is clear that all of his combinations can easily be performed on an organ.

Butler’s reliance on the fugue’s presentation in keyboard score, unlike the open score in which the rest of the cycle is written, to reinforce his claim that the Fuga a 3 Soggetti does not belong to The Art of Fugue is unconvincing. A similar case exists in the Musical Offering, where the six-part ricercar appears in both open and keyboard scores. Never was this fact presented as an argument claiming that this ricercar does not belong to that cycle. Indeed, the Fuga a 3 Soggetti appears in Philipp Emanuel’s announcement among the last pieces that are unrelated to the cycle. However, since all these pieces are eventually included in the Original Edition, it is hard to accept this as a valid argument.

Butler highlights the long period of time that separates the composition of the main corpus of P 200 and P 200/1–3 and dates the Fuga a 3 Soggetti at the very end of the composer’s life. This is quite an indefinite period, which requires a more precise chronological perspective. The manuscript is dated as written between August 1748 and October 1749,34 and the main body of P 200 as completed during 1746.35 Bach, however, continued to work on The Art of Fugue during 1747 until August 1748, with several intermittent breaks, which occurred naturally.36 This specific time gap coincides with the period of approximately one year between the first and the second versions of The Art of Fugue. During this time Bach worked on the composition of the Mass in B minor, making it comparable to other events that took place during the composition process of The Art of Fugue. This timetable can hardly support an assumption claiming the Fuga a 3 Soggetti to be chronologically unconnected to The Art of Fugue.

Why does Bach’s autograph of the Fuga a 3 Soggetti (P 200/1–3) end on bar 239?

It is often considered that The Art of Fugue remained unfinished, the widespread notion being that the composer had not succeeded in completing it. The manuscript of the last Contrapunctus (BWV 1080/19 in Schmieder’s Catalogue)37 seems abruptly cut off on bar 239, at the point where the final section of the fugue should normally appear. While this seems to exclude any doubts on this account it may nevertheless be worthwhile to consider whether the break in this bar simply means that the fugue is unfinished, or whether this fact may have some additional meaning.

There are several scholars who question the prevalent notion and consider the possibility that the fugue had been completed.38 Christoph Wolff writes: ‘The last fugue was not left unfinished as it appears today and, in fact, The Art of Fugue must have been a nearly completed work when Bach died’.39 The author also offers an explanation as to why the piece stopped at this particular place, confirming that the fugue was finished and the stop was not coincidental.40 Stating that Bach did not intend to continue the process of composition, he presents three propositions:

• The autograph under consideration is a ‘composition manuscript’, that is, a manuscript created during and through the process of composition.41

• The composition of a quadruple fugue should start from some draft fragment (which Wolff named ‘fragment x’), in which all four themes are stated together. This fragment had to exist in reality, but eventually was lost.42

• Bach did not intend to continue writing after bar 239,43 because it had to be followed by the closing part of the fugue, built (in a normative fugue fashion) as a sequence of joint statements. The next step would be, therefore, writing it down, using fragment x as a model and intercalating the voices in various combinations. It was thus unnecessary to continue the composition: the rest of it would be derived from said fragment x.44

There is no reason to deny that prior to composing a quadruple fugue, some preliminary work has to be done. The purpose of such work is to provide options for simultaneous combinations of all of the themes. Without such preparation work the composition of a multi-theme fugue is simply impossible.45 Moreover, it makes perfect sense that such a combination did exist as a draft on paper.

Wolff’s assumption that Bach did not intend to continue the manuscript after bar 239 seems further substantiated by the fact that the bottom part of the fifth and last page of the autograph is so carelessly lined that it is impossible to continue writing on it. The sheet had been so spoiled that if Bach nonetheless decided to write on it, he had in mind only a few bars, needing just the top part of the page.46

Nevertheless, Wolff’s explanation for the cut at bar 239, according to which the rest of the fugue was already imparted in fragment x and was therefore unnecessary here,47 is yet not convincing enough. First, there could be more than one reason for the cut (other reasons will be suggested below). Second, and more important: the existence of fragment x does not necessarily imply that the fugue was completed; this fragment could provide a basis for many variants that would function as the composition’s closure. If the fugue had not been explicitly written down to its end (at least as a draft), a whole process of composing, albeit simplified by Bach’s well-prepared fragment x, was still to be implemented. After all, the closure of a multi-theme fugue may contain any number of statements and various episodes or none at all. It is impossible, thus, to determine the closure—or the actual length—of a specific fugue based solely on one fragment x, even if its existence is highly plausible. The exclusive reliance on such a possibility does not provide enough grounds to conclude that the last fugue ‘was not left unfinished’, or, moreover, that the entire Art of Fugue had been completed.

While the question of whether this fugue was completed or not remains open, it is closely connected with another important starting point: the nature and the function of this particular autograph. The widely accepted assumption, shared by most scholars, is that the autograph is a composition manuscript. This point, however, is not so obvious and requires further consideration.

A composition manuscript or an engraver copy?

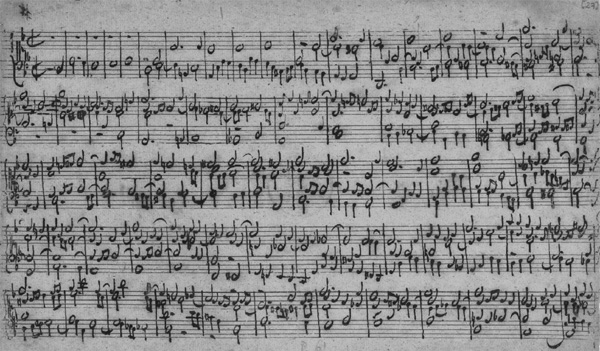

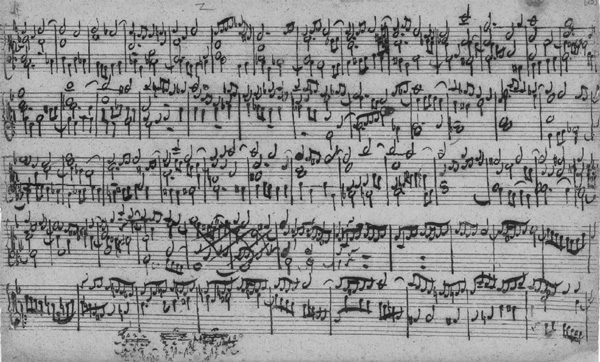

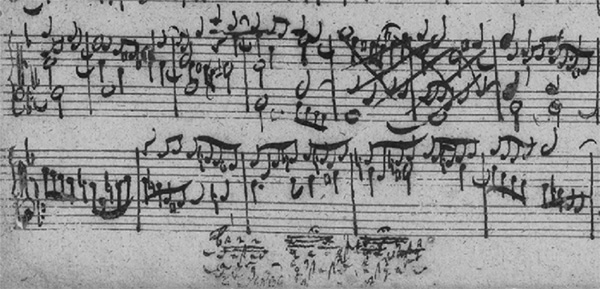

Indeed, the manuscript does look like a composition copy. It would suffice to look at its fifth page (Figure 18.4) in order to confirm this impression.

The first thing that one may notice in this page is its messiness: the handwritten notes—note stems flung carelessly in various angles, smears and expanding ink stains—suggest quick writing. The musical content on this page is drafty, too: each one of the four voices ends on a different point. Indeed, all this points at a composition process abruptly interrupted. The inscription made by Carl Philipp Emanuel, ‘Ueber dieser Fuge … ist der Verfasser gestorben’ [Over this fugue… the author died] only reinforces this impression. How else could one interpret the given manuscript, if not as one created in the process of composition?

If, however, the autograph in its whole is critically analysed, some facts surface which might puzzle supporters of the ‘compositional draft’ theory. For example, the paper’s quality, the handwriting’s features and the specific corrections of the autograph’s first page (Figure 18.5) show traits that would hardly fit the notion of a composition manuscript.

All of these elements deserve closer examination.

The paper

The paper of this manuscript is thin and porous. Such paper was used for engraver copies (Abklatschvorlagen). It had to be porous in order to better absorb the oil varnish and thin, to allow the mirrored text to be better seen in the verso after the oiling. Examples of Bach’s compositional manuscripts written on paper of this kind have never been seen and as of today are unknown.

Still in agreement with traditional engraver copies, the music text is written only on the recto of each sheet; all verso sides were left blank. The bulk of evidence showing that Bach did his best to save on the high cost of paper makes such uncharacteristically prodigal use of paper for a draft highly unlikely.48 The list of errata prepared by Carl Philipp Emanuel after his father’s death and written on the verso of the fifth sheet only confirm this impression. In addition, his other son, Johann Christoph Friedrich mentions some ‘new conception’ [‘… und einen andern Grund Plan’] that his father implemented in the last version of The Art of Fugue. The paper, therefore, supports the view of the discussed manuscript as an engraver copy rather than as a compositional draft.

The handwriting

The handwriting on the first page of the manuscript is very tidy. The writing pace is slow, as when meticulous attention is paid to calligraphy; the notes are large, particularly the note heads which are here larger than usual. Similar examples in Bach’s scores exist exclusively in engraver copies and in most fair manuscripts (sometimes intended as gifts) but never in composition manuscripts.

The polyphonic writing is rhythmically aligned. This would be fairly impossible in draft, particularly when composing polyphonic music, let alone one rich in imitations and complex counterpoint combinations.

The rastering of the first four pages was performed with a ruler. Bach had stave-lined with a ruler only engraver and gift copies, but never his composition manuscripts. The fifth sheet, however, looks different. It is rastered by hand with no use of a ruler.

Some scholars believe that the four first pages of the fugue were on leftovers of paper that remained unused after Bach finished the four canons, because Bach used here the same kind of paper, and these pages were similarly lined: five two-stave systems on each page.49 Judging by the Original Edition of 1751, however, we see that Bach prepared the engraver copies of the canons himself, which means that he knew precisely how much room he needed to write them down and the amount of paper this would require. Taking into account that Bach always minimised his use of paper, the hypothesis that he prepared four additional pages without being sure that he would fill them up seems improbable.

Thus, not only the peculiarities of the paper, but also the characteristics of the note writing on the first four pages contradict the appearance of Bach’s composition manuscripts. On the other hand, they reinforce the argumentation for the first four pages to be interpreted as engraver copies.

Corrections and amendments

In many cases the kind of corrections on a page allows detection of the circumstances under which they have been performed: during the composition or the copying, after the composition or after the copying. Not focusing now on the specific features of Bach’s corrections (which are meticulously researched and classified in the two-volume study by Robert L. Marshall),50 I will only bring examples of the corrections that are relevant for the present discussion.

The first correction appears at the very first page of the manuscript (Figure 18.5, bars 19–20). It is difficult to establish what exactly was written in bar 19 before the correction. However, it can be clearly seen that the previous writing had been scraped off with a knife,51 the stave lines accurately restored and the new musical text written on them. The new note writing was performed carefully, keeping the calligraphic style before and after this point. Why, all of a sudden, would Bach care so much about calligraphy in a composition manuscript? He never did so in composition manuscripts, and not even in many fair copies, as, for example, in the main body of P 200.52 Once an error was noticed, or when Bach changed his mind right after he wrote something down, he would usually insert the correction above or, if that was impossible, simply strike out what should be corrected and continue to compose or to copy further on the same stave. Examples of this practice can be seen in other autograph manuscripts, for example, in the Confiteor section from the Mass in B minor, BWV 232, where whole bars are crossed out and the correction written below the system.53 This is exactly the type of amendment that appears on the second page of P 200/1–3. Its appearance—quite messy, with multiple corrections—points at an entirely contradictory conclusion, suggesting that this is, actually, a composition manuscript (Figure 18.6).

Two bars—113 and 114—were crossed out and three bars indicated to be inserted instead. Note that the correction, in German organ tablature, is written at the bottom margin of the page.

Our attempt to reconstruct the process of this correction starts with the notes that were originally written in bars 109–15 (Figure 18.7).

The musical text seems fairly typical, except for two questionable points that are not quite attuned to Bach’s style. The first point is the absence of a subdominant before the dominant–tonic closing cadenza in bars 113–14; the second is the melodic motion of the bass in bars 112–13, which is atypical for Bach when preparing a dominant in cadenzas. Such motion cannot be found anywhere in the entire Art of Fugue. The coincidence of these two uncharacteristic gestures may suggest that one bar, presenting the subdominant degree, was missed. Such proposition is supported by Bach’s own correction (Example 18.4).

Clearly, Bach did not notice the mistake on the spot. If he had discovered it on time (that is, immediately after writing the following bar, in this case, bar 114 or even bars 113–14), and if this were indeed a composition manuscript, he would most probably have acted like he did in similar cases: either write the correction above the already written bars or cross out the incorrect bar(s) and continue his writing thereafter. This analysis indicates, then, that Bach made the corrections while copying and not in the process of composition.

A whole complex of factors—the quality of paper, the style of musical graphics and the character of corrections—conveys that the writing of these pages took place not in the process of composition but while copying. Moreover, many other signs suggest that this was not intended just as a copy, but rather as a copy for engraving.

This first conclusion deduced from the analysis of the first four sheets of the autograph is, then, that this is an engraver copy on which a mistake was found, requiring a correct copy to be written on a new page. The fifth sheet of P 200/1–3 (Figure 18.4), however, presents a completely different picture.

The fifth sheet of P 200/1–3

As mentioned earlier, this last sheet looks significantly different from the other ones in this supplement: its format and the sort of paper differ from the first four pages; there are many stains, making the page look quite messy; the writing speed is higher, the notes are smaller than on the previous pages, and the handwriting does not manifest any intention of calligraphic writing. Finally, the staves are rastered by hand and quite negligently, to the point that music cannot be written on the bottom staves. On the other hand, the musical text is absolutely clear, and furthermore all proportions of the musical alignment are carefully kept, enhancing the clarity of the musical text.

Consequently, it is quite safe to state that all the characteristics of the fifth page reflect Bach’s striving to achieve one single goal: readability.54 All the rest does not seem to be essential. A manuscript of this kind would usually be given to a copyist; it only needed to be clear, to minimise the chances of copyist errors.

What could be the reason for this difference between the first four pages and the fifth one, which looks as if it belonged to another manuscript? What change of intentions could it reflect?

In our view, the discussed autograph reflects quite an unusual process of copying, during which the relation of the composer to this manuscript had changed, which leads to a second and more accurate conclusion concerning P 200/1–3: while the first page is, indeed, an engraver copy, the fifth (and last) one is just a plain copy, intended for a copyist who would prepare of it an engraver copy.

The situation is quite unusual, and we cannot but be curious why it emerged. Other circumstances accompanying this story are equally intriguing. For what did Bach need an engraver copy? Why did he need a plain copy? And, why did he abandon the initial idea in the process of preparing the manuscript?

The purpose of the engraver copy is unequivocally clear: Bach intended to send this fugue to print. Note, however, that the fugue is written on a two-stave system (clavier version), while all the other contrapuncti of The Art of Fugue are written in open score. This is crucial, because this version could not be used for the publication of The Art of Fugue. Hence the purpose of this two-stave variant of the fugue is utterly unclear. It was mainly this discrepancy that drew the attention of Gregory Butler, who concluded that Bach did not intend to include this fugue in The Art of Fugue.55 The facts, however, suggest another interpretation.

The Fuga a 3 Soggetti in the context of Bach’s social life

The period between March 21, 1749, and the beginning of March 1750 is a meaningful time in Bach’s life: on March 21, 1750 he would celebrate his 65th birthday. This age had special significance for a member of the Society of Musical Sciences,56 to which Bach had belonged since 1747. According to the constitution of the Society, each member had to make an annual contribution of an original work. To create a work was not enough: it should be published. The members who reached the age of 65 were assigned to the category of pro emerito and were released from the obligation of this annual contribution, as well as from the annual membership fee.57

Bach’s contribution for 1747 appears in the portrait made by Elias Gottlob Hausmann (1746), in which the composer holds the score of the six-part triple canon. In this form, however, it can be considered as a ‘legitimate’ publication only conditionally. In reality, it had been published in Mizler’s Musikalische Bibliothek. In 1748 Bach most probably contributed the Einige canonische Veraenderungen über das Weynacht-Lied: Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her, BWV 769. The piece was engraved by Balthasar Schmid58 and printed in Nüremberg.

The year 1749 was supposed to be the last time that Bach would be expected to contribute to the Society. From 1750 on, he would become one of the pro emeriti and be released from this obligation. However, looking through the works he composed in 1749 (as far as the preserved manuscripts allow), one cannot attest to any particular piece as fitting this purpose. The only one that meets the criteria is The Art of Fugue. Indeed, the hypothesis that the composer could use it for this purpose is quite popular among Bach scholars and most categorically fostered by Hans Gunter Hoke.59 His principal arguments are based on the facts that The Art of Fugue completely met the requirements of the annual contribution and that in 1750 Bach turned 65. Accepting Hoke’s argumentation, we would like to draw attention to some details that are important for the present discussion, but were not addressed in his work.

One of the peculiarities of the Society of Musical Sciences was that it worked by correspondence; even the title of its constitution includes the words ‘correspondirenden Societät’.60 There was a particular ‘packet’ that circulated among its members through the post service. The packet contained various materials: information on current events, discussions of works composed by the Society’s members, the works themselves (including those that had been considered as their annual contributions (in case they were not published in the MMB). Mizler’s letter from September 1, 1747, from Końskie (Poland) to the Society member Meinrad Spieß from the Irsee Monastery gives us an idea about the size of the material that the envelope could contain.61 The piece Bach mentioned was obviously the six-part ricercar from the Musical Offering. The size of its printed copy is seven pages on four sheets. As already mentioned, Bach’s contribution to the Society in 1748 was the Einige canonische Veraenderungen über das Weynacht-Lied: Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich her, BWV 769. Its size in print was six pages on four sheets. It is plausible, therefore, that the size of a contribution within four sheets was considered optimal for these contributions, and Bach took every step to fit into this. In the case of BWV 769, for example, the first, second and third variations present the canon’s risposta in a cryptic form (while even in the autograph of this work it is written in full). Else, for a full presentation, Bach would need 18 more staves, which would exceed the four sheet required format (printing the end of his music on the back cover of an edition would not have been considered bon ton). Further, it is clear that in this edition Bach strove to avoid a page turn in the course of any single variation. Were the canon of the first two variations not cryptic, the fifth (last) variation would have a page turn in the middle of its third canon. Encrypting certain parts allowed Bach to provide the performer with a comfortable reading, to save a whole page and to fit the composition into the desirable format of four sheets.

The Original Edition of The Art of Fugue is large (70 pages) and weighty. Clearly, its dimensions would not allow fitting into the Society’s packet. However, if only the Fuga a 3 Soggetti were submitted, and not as a score but in clavier format, presenting only the fuga recta, its size and weight would perfectly fit the Society’s ‘packet’. Indeed, as calculation shows, the size of the fuga recta of the last piece of The Art of Fugue would require nine pages if written in open score62 and even less if written in a clavier reduction. For comparison: the six-part ricercar from the Musical Offering is seven pages long in open score and only four pages in clavier reduction.63 Bearing in mind that after bar 239 of the last fugue there were still approximately 90 bars of music to be written, and judging by the density of writing in P 200/1–3, this would take less than two pages that should be added to the existing four. In other words, the completed fugue in clavier layout would be about six pages long. Including the title page and the empty verso of the last sheet would render four sheets, the exact format of materials hitherto sent to the Society’s mail. Considering the likelihood of such a sequence of events, Bach’s intention to publish this fugue in clavier layout for Mizler’s Society seems quite feasible: at least in size it fully corresponds to the format of the Society’s ‘packet’. Our third conclusion, thus, is that Bach was preparing the engraver copy in order to publish it in clavier layout as his creative contribution to the Society of Musical Sciences for 1749.

Why, however, would Bach desert the idea of making this engraver copy and, during the course of his work, switch to the preparation of a plain copy?

The first four pages of the fugue exhibit characteristics that prove Bach’s diligent concern for calligraphic quality, which was a necessary condition for an engraver copy. However, the bar missed in the process of copying and the subsequent correction spoiled the second page, forcing Bach to abandon his original plan.

In its clavier version the fugue could not be added to The Art of Fugue: for that Bach would need to prepare an engraver open score of this fugue. At this stage, however, he was physically too weak to do it himself and, besides, he realised that his calligraphic efforts would not match the required quality anymore. The next step would be to use the service of an engraver, for whom a plain and easily readable copy would be provided. It is highly likely that this is exactly what happened. Failing to prepare the engraver copy on his own, Bach simply decided to use these five pages as copies for a copyist.

Bach had to copy these pages from some draft. As mentioned earlier, prior to composing a quadruple fugue one should have a thoroughly checked combination of all the four themes in one common statement. Only following this procedure, other sections based on each of the themes could be written.64 It is in such sections that most of the corrections, so typical of a composition manuscript, can be found, particularly in the contrapuntal constructs characteristic of fugues. An analysis of the preserved part of the P 200/1–3 indeed presents such structures in high density. The draft of this fugue surely was brimming with corrections, making it hardly readable. While the composer was able to understand it, a copyist would most probably find it absolutely undecipherable. On the other hand, the closing section of the fugue had to be built upon the previously prepared joint statement of all of the themes. It is very likely, then, that this particular section of the fugue’s draft was clear enough to provide a reference for an engraver copy.65 It was unnecessary, therefore, to copy it yet again, particularly considering its size—about 90 bars—and the fact that Bach was enduring, by then, serious difficulties with his vision.

Our fourth conclusion, therefore, is that there are grounds to assume that Bach wrote the first four pages of the P 200/1–3 as an engraver copy, while the 12 remaining bars, written on the fifth page, were a fair draft intended for a copyist.

Our main (and last) conclusion, however, is that based on our interpretation of the data found in the analysis of P 200/1–3 there is reason to contemplate The Art of Fugue as a completed composition. Consequently, it might have been published by Bach himself, were he still alive, rather than by his sons, which would have been possible if not for the unfortunate visit of the guest celebrity, the oculist John Taylor, in Leipzig.

The fate of the copies

What happened to the copies of this fugue, the one for clavier and the second in score layout?

The clavier layout copy

There are still no traces of the copy intended for submission to the Society of Musical Sciences. For the time being it can only be regarded as Bach’s intention, deduced from the P 200/1–3. It is highly probable that it was never actually created, but incompletely preserved only in this autograph. This would mean that Bach’s duties for the Society of Musical Sciences for the year 1749 were not fulfilled. It is unlikely that Bach put himself in an awkward position versus his colleagues, violating the constitution of the Society. However, the eighth clause of the Society’s constitution specifies special conditions, among which health problems are considered. According to this clause, only a prolonged illness of a Society’s member can justify missing the presentation of an annual contribution: ‘Wer es unterlässet, liefert zur Casse 1 Rth. und entschuldiget nichts, als langwierige Krankheit’.66 Indeed, this is exactly what happened to Bach.

The open score copy

We would hardly know anything about the existence of this engraver copy, except for the copyist’s mistake.67 The additional pagination that Bach used in the second part of The Art of Fugue allows us to delineate the number of pages reserved by the composer for the quadruple fugue. The copyist tried to save one page, writing the musical text of the fugue more thriftily than the composer had planned. Subsequently, Bach had to exchange the position of several pieces within the cycle. The traces of this story can be found in another autograph, which could serve as topic for another discussion.68 Here, however, the most important point is that the engraver copy of the score for the edition of The Art of Fugue was executed by the copyist to whom Bach handed the following materials: five pages of P 200/1–3 (four written as engraver copies and one as a fair draft) and the end of the (now lost) draft in which the text was clearly legible, because it was based on the (now lost) composition fragment x.69

Notes

1 The chapter was formerly published in Russian as an article: Anatoly Milka, ‘O sud’be poslednego vznosa I.S. Bakha v “Obshchestvo muzykal’nykh nauk”’ [On the fate of J.S. Bach’s last contribution to the Society of Musical Sciences], in A. Dolinin, I. Dorochenkov, L. Kovnatskaya and N. Mazur (eds.), (Ne)Muzykal’noe prinoshenie ili Allegro Affettuoso [(Non)-Musical Offering or Allegro Affettuoso]: Collection in Honor of Boris Katz toward his 65th Anniversary (St Petersburg, 2013), pp. 7–21. Also in German, Anatoly Milka, ‘Warum endet die Fuga a 3 Soggetti BWV 1080/19 in Takt 239?’, BJ 100 (2014): pp. 11–26.

2 The obituary was first published in MMB IV (1754): pp. 158–76; reprinted in BD III/666, pp. 80–93; translated to English in NBR, no. 306, pp. 295–307.

3 [The Art of The Fugue. This is the last work of the author …] MMB IV (1754): p. 168; BD III/666, p. 86; NBR, no. 306, p. 304.

4 [From now on it is not The Art of Fugue, but the Mass in B minor that should be regarded Bach’s opus ultimum.] Yoshitake Kobayashi, ‘Bemerkungen zur Spätschrift’, p. 462.

5 Yoshitake Kobayashi, ‘Zur Chronologie’, p. 66.

7 Ulrich Prinz (Ed.), Johann Sebastian Bach: Messe H-Moll: ‘Opus ultimum’, BWV 232—Vorträge der Meisterkurse und Sommerakademien J.S. Bach, 1980, 1983 und 1989 (Stuttgart, 1990). For particular interest in this volume see Robert L. Marshall, ‘Bachs H-moll-Messe: Zur Quellensituation und Überlieferung’, pp. 48–67. Hans-Joachim Schulze, ‘J.S. Bachs Missa h-Moll BWV 232-I. Die Dresdener Widmungsstimmen von 1733: Entstehung und Überlieferung’, pp. 84–102, and Yoshitake Kobayashi, ‘Bachs Spätwerke: Versuch einer Korrektur des Bach-Bildes’, pp. 132–50.

8 Wolff, Bach: Essays, p. 27.

9 Wilhelmi, ‘Avertissement’, pp. 101–5; BD V/C 638a, pp. 182–3; NBR, no. 281, pp. 256–8.

10 BD III/645, pp. 12–13.

11 Editor’s note: in Bach literature, this essay is usually referred to as the ‘obituary’. To avoid confusion, this term is kept here, too. This, however, is not the original title of Philipp Emanuel and Agricola’s essay. The obituary was published as the third part of the ‘Denkmal dreyer verstorbenen Mitglieder der Societät der Musikalischen Wissenschafften’ [Memorial for three deceased members of the Society of Musical Sciences], MMB IV, (1754): pp. 129–76. The part honouring J.S. Bach, written by C.P.E. Bach and Johann Agricola, is the third among these, starting on p. 158. The title Denkmal, suggests a ‘memorial essay’ rather than ‘obituary’ (which in German would appear as Nekrolog, Nachruf or Todesanzeige). The word ‘Nekrolog’ does appear however, for the first time in relation to this particular essay, in BD III/666, p. 80, in a very short introduction to the text, probably following the late eighteenth-century tradition of lengthy obituary writings (indeed titled ‘Nekrolog’). However, the late date—four years after J.S. Bach’s death (although its first draft might have been written earlier—see note 17), its sheer length and the character of its content imply a memorial essay rather than an obituary.

13 Die Kunst der Fuge, Original Edition, (Leipzig, 1751); reprinted in BD III/645, pp. 12–13; translated in NBR, no. 284, pp. 259–60.

14 Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg, Die Kunst der Fuge durch Herrn Johann Sebastian Bach, ehemahligen Capellmeister und Musikdirector zu Leipzig. Vorbericht, in der Leipziger Östermesse, 1752. Reprinted in BD III/648, p. 15; translated in NBR, no. 374, p. 376.

15 MMB IV (1754): p. 168; reprinted in BD III/666, p. 86; translated in NBR, no. 306, p. 304.

16 Also in BD III/631, p. 3; translated in NBR, no. 285, p. 260.

17 A second advertisement of subscriptions was issued a month later, on June 1, 1751 in the Leipzig newspapers. Its style reveals that Emanuel wrote that one, too.

18 According to Mizler, C.P.E. Bach’s first version of this essay might have been written as early as the end of 1750 (see NBR, no. 306, p. 297, note 28). However, it is more than likely that in the time between 1750 and 1754, when the essay was published, it went through several corrections and additions.

19 [Fugue was his element. Here he showed himself each time in his true Bachian shape.] Adolf Heinrich Friedrich Schlichtegrol, Nekrolog auf das Jahr 1795 (Gotha, 1797), pp. 268–84, quote from p. 281; See Peter Wollny, ‘Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach und die Teilung des Vaterlichen Erbes’, BJ 87 (2001): p. 67.

20 Charles Burney, The Present State of Music in Germany, the Netherlands, and United Provinces, or, the Journal of a Tour through Those Countries, Undertaken to Collect Materials for a General History of Music. By Charles Burney, Mus. D., in Two Volumes (vol. 2, London, 1773), p. 323; reprinted in BD III/777, p. 249.

21 Ernst Suchalla (ed.), Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: Briefe und Dokumente: kritische Gesamtausgabe, vol. 1 (Göttingen, 1994), documents 3–5, pp. 9–13.

23 It is a norm in the composition process of complex counterpoint that the initial idea must include its derivatives, and careful thought must be given to the peculiarities of various counterpoint types, because each type carries and implies a set of its own limitations.

24 For relevant eighteenth-century German terminology see, for example, Johann Gottfried Walther, Musicalisches Lexicon oder Musicalische Bibliothec (Leipzig, 1732), p. 180; Johann Mattheson, Kern melodischer Wissenschaft (Hamburg, 1737), p. 137 and his Der volkommene Capellmeister (Hamburg, 1739), p. 383; Mainard Spiess, Tractatus Musicus Compositorio-Practicus (Augsburg, 1745), p. 134; Wilhelm Marpurg, Abhandlung von der Fuge (Leipzig, 1753), p. 10.

25 Martin Gustav Nottebohm, ‘J.S. Bach’s letzte Fuge’, Musik-Welt, 20 (March 1881): p. 234.

26 Gregory Butler, ‘Scribes’, pp. 111–24.

27 ‘One of the most persistent myths surrounding The Art of Fugue is that the collection was to be crowned with a quadruple fugue, the ‘incorrectly’ titled Fuga a 3 Soggetti that survives in autograph form.’ Ibid. pp. 116–17.

28 Butler mistakenly relates this announcement to the second edition (ibid.); however this announcement is dated May 7, 1751, more than four months before the first edition’s publication. Emanuel’s announcement concerning the second edition merely informed the availability of its copies for the subscribers.

33 Butler relies here on Christoph Wolff’s opinion. Ibid. p. 122, note 24.

34 Kobayashi, ‘Zur Chronologie’, p. 62.

37 Wolfgang Schmieder, Thematisch-systematisches Verzeichnis der musikalischen Werke von Johann Sebastian Bach (Leipzig, 1961), p. 609; Alfred Dürr and Yoshitake Kobayashi, Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (Wiesbaden, 1998), p. 445.

38 Christoph Wolff, ‘The Last Fugue: Unfinished?’ in Current Musicology, 19 (1975): pp. 71–7, reprinted in Wolff, Bach: Essays on His Life and Music, pp. 259–64.

39 Wolff, ‘The Last Fugue’, p. 76.

41 Not all scholars interpret Wolff’s conclusion in this way. Gregory Butler, being convinced that Wolff considers the given autograph to be a fair copy, writes in reference to p. 72 in Wolff’s article: ‘both the status of this source as fair copy and also physical evidence in the source itself led Wolff to the conclusion that the work had been completed by Bach’ (Butler, ‘Scribes’, p. 122, note 27; emphasis added). Butler’s interpretation, however, is incorrect: Wolff does not consider this manuscript to be a fair copy. On the contrary, he describes it as a compositional manuscript: ‘…Beilage 3 represents the composition manuscript …’ (Wolff, ‘The Last Fugue’, p. 73); see also next note.

42 ‘… The combinatorial section of the Quadruple Fugue in a manuscript (hereafter designated fragment x) that originally belonged together with Beilage 3, but is now lost’. Ibid. p. 74.

43 ‘… Bach obviously had never planned to fill the sheet from top to bottom, in other words that he stopped writing deliberately at m. 239’. Ibid. p. 71.

44 ‘… He [Bach—A. M.] stopped at m. 239 … because the continuation of the piece was already written down elsewhere, namely in fragment x’. Ibid. p. 74.

45 ‘… Bach had no choice but to start with the combinations of the four themes before writing the opening sections of the fugue’. Ibid. p. 74.

46 ‘Surely he used the last page only because he needed a sheet of music paper for just a few bars; since he never wasted paper, such a piece could serve his purpose’. Ibid. p. 72.

48 Scholars often pointed at this fact. See, for example: Wolff, ‘The Last Fugue’, pp. 72–3; Butler, ‘Scribes’, p. 122; Hofmann, NBA KB VIII/2, p. 82.

49 See for example: Wolff, ‘The Last Fugue’, p. 73.

50 Robert Lewis Marshall, The Compositional Process of J.S. Bach: A Study of the Autograph Scores of the Vocal Works. Princeton, 1972, two volumes. See also: Tatiana Shabalina, Rukopisi I.S. Bakha: klyuchi k tainam tvorchestva [J.S. Bach’s manuscripts: keys to the mysteries of his work] (St Petersburg, 1999), pp. 118–28.

51 About Bach’s use of the scraping knife for corrections in his scores see: Yoshitake Kobayashi, ‘Bachs Notenpapier und Notenschrift’, in Susanne Spannaus et al. (eds), Thüringer Landesausstellung, vol. 1 (Erfurt, 2000), p. 427.

52 ‘The main portion of the autograph—referred to as P 200, after its call number—represents a fair copy’. Wolff, Bach: Essays, p. 268.

53 Autograph D–B Mus. ms. Bach P 180 in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz; see correction in bars 140–42.

54 Wolff, ‘The Last Fugue’, p. 72.

55 ‘… as I have argued, the Fuga a 3 Soggetti was never to have been included in the collection [The Art of Fugue—A.M.]’. Butler, ‘Scribes’ p. 118.

57 ‘Wenn ein Mitglied 65 Jahr alt ist, so ist er für verdient (pro emerito) zu halten, und von Arbeiten frey, und nur zu einem freywilligen Beytrage zur Casse verbunden …’ MMB, III/2 (1746): pp. 355–6.

58 Schmid was probably one of Bach’s former students. He also took part in the edition of Clavierübung III.

59 Hans Gunter Hoke, Zu Johann Sebastian Bachs ‘Die Kunst der Fuge’ (Leipzig, 1974), pp. 14–15.

60 ‘Gesetze der correspondirenden Societät der musikalischen Wissenschaften in Deutschland.’ MMB III/2 (1746): p. 348.

62 The calculation is based on the fact that there are two additional paginations in P 200/1–1. Their analysis shows that in the final stage of the work on The Art of Fugue the interchanging of canons took place. This interchanging enables the calculation of the number of pages that Bach reserved for the last fugue (recta and inversa). Since this fugue, like the two previous, was a mirrored one and had the structure of rectus + inversus, it appears that Bach reserved for it 18 pages in total, that is, nine pages for each section. See also Milka, Iskusstvo fugi, pp. 186–91; Milka, ‘Zur Datierung’, pp. 53–68.

63 There is an autograph of two-stave version of the six-part ricercar from the Musical Offering (P 226). It takes four pages.

64 Usually it is the exposition of the first theme, followed by the expositions of the second and of the third themes. These sections are obligatory. However, after the expositions free sections may follow, which is exactly the case in this fugue. Here, the exposition of the fourth theme is absent, because in this particular fugue it is used as cantus firmus.

65 If Christoph Wolff considers fragment x to be a ready ‘combinatorial section’ of the fugue, then the section based on it must be at least clear.

66 [The one who will not fulfil this, should pay one Reichsthaler, and, only long illness can serve as a justification.] MBB III/2, p. 350.

67 As Peter Wollny established, Bach’s main copyist then was his pupil Johann Nathanael Bammler. Wollny, ‘Neue Bach-Funde’, p. 44. For more information about the error of this copyist see in Milka, ‘Zur Datierung’, pp. 65–7.

68 Milka, Iskusstvo fugi, pp. 174–90 please see detailed analysis and description in Chapter 11.

69 Unfortunately, these materials are lost, but signs of their existence are present in the Autograph and in the Original Edition of The Art of Fugue.

![]() -A-C-B

-A-C-B![]() ], to conclusion; accordingly it was wished to compensate the friends of his muse by including the four-part church chorale added at the end, which the deceased man in his blindness dictated on the spur of the moment to the pen of a friend.]13

], to conclusion; accordingly it was wished to compensate the friends of his muse by including the four-part church chorale added at the end, which the deceased man in his blindness dictated on the spur of the moment to the pen of a friend.]13