AS THE HURRICANES whipped around the dazzling summit of the ice dome over Ben Lomond and a glaring sun beat down from a cloudless blue sky, Scotland lay sleeping. Under the crushing blanket of the ice, the landscape was compressed, hidden, waiting – except in one place. From bore-holes drilled through the crust of primeval soils, sediments, clays and rocks, geologists have found evidence that the western edge of the ice sheet over northern Europe reached only as far as the Hebridean island of Islay. The grip of the glaciers slackened on a line along the sea lochs of Gruinart and Indaal. The Rinns, the eastern wing, was cut off from the rest of the island around 20,000 BC, the time of the Ice Age’s zenith and when temperatures were at their coldest.

The storms and dark clouds of the depressions at the edge of the glaciers will often have obscured it but the hill dominating the Rinns was high enough to escape the ice. Beinn Tart a’Mhill appeared like a dark beacon in the pitiless white landscape and, although they too will have been scarfed in cloud, the Paps of Jura to the east will have risen above the ice desert. This pocket of land, the Rinns, was not bulldozed and scarted by the rumble of glaciers, and deposits of flint-rich sediments were left undisturbed, an anomaly which would later become important.

When the ice began to shrink back north- and eastwards, around 15,000 BC, Islay slowly revealed itself. By 12,000 BC, the southern Hebrides were clear, a tundra emerged and, as the great weight of the ice lifted, the land rose and the Rinns were reunited with eastern Islay.

Near the village of Bridgend at the head of Loch Indaal and almost precisely on the line of the edge of the glaciers, a flint arrowhead was found. It was not just any arrowhead. In the summer of 1993, a group of archaeologists was field walking, looking for objects turned up by the plough. The arrowhead was of a specific and very early type known as an Ahrensburgian point. In Schleswig-Holstein, the neck of land linking Germany and Denmark, archaeologists discovered a site of mass slaughter. Through the narrow Ahrensburg Valley, huge herds of reindeer had once migrated north to summer pastures, crossing a prehistoric land bridge to what is now southern Sweden. At Stellmoor thousands of reindeer bones were found at the edge of a lake. In the anaerobic mud, excavators came across well-preserved pine arrow shafts and a huge scatter of flint tools. Often lodged in the skeletal remains of the reindeer were the distinctive arrowheads that became known as Ahrensburgian points. Not only did the finds signal the arrival of the bow and arrow in northern Europe, they also allowed the reindeer ambushes to be securely dated. It appears that the hunters lay in wait around the year 10,800 BC.

The Ahrensburgian point picked up in a ploughed field on Islay is not unique; others have been found on Tiree, Jura and Orkney but their find-spots were not securely recorded and some were damaged. Nevertheless the arrowhead recognised in 1993 is very suggestive. Some time in the eleventh millennium BC, soon after the retreat of the ice, hunters were venturing north into the emptiness that was Scotland. Probably paddling the skin boats known as curraghs, at least one summer expedition appears to have made landfall on Islay and perhaps Tiree and Jura. Pioneers explored the islands and the coastline and it seems that they brought bows and arrows with them. Even if they stayed for only a short time, these were likely to have been the first people to see Scotland for 15,000 years or more.

Summer temperatures were rising to a maximum of 17° Celsius but the winters remained very cold at an average of only 1° Celsius. Much of Scotland became tundra after its release from the ice, and then the sort of summer grasslands grew that sustained the vast herds of wild horse and bison so beloved of the cave-painters of Lascaux and elsewhere. It may have been cold enough for reindeer when the pioneers came to Islay in 10,800 BC but their quarry is more likely to have included deer. Jura is an anglicisation of Diura and from Gaelic it translates as Deer Island. The hunters probably stalked other species such as wild horse, wild cattle and perhaps boar. Seals may have colonised the shoreline and, being slow moving on land, they will have made easy prey.

For millennia water was the most reliable highway, a connector rather than a barrier. And, if a trackless wildwood was beginning to creep northwards by the time the hunters came, then coastal waters, lochs and rivers will have been an easier and faster means of travel. Hide boats were easy to make and could be assembled in a morning. A frame of whippy green rods is lashed together with cords (animal sinew is reliable) into the shape of a hull and then stiffened with wooden thwarts which can acts as benches for paddlers or rowers. Then a patchwork of fresh hides is sewn together and stretched over the frame. When this membrane dries, the hides become taut and pull the curragh into shape. Caulking with resin or animal fat along the seams works well enough although it is likely that baling was a constant duty. These ancient craft were made (and continue to be made in south-western Ireland) from material readily to hand and they were very versatile. Compared with much heavier wooden boats, they have a shallow draught measured in centimetres and, if a river passage becomes difficult because of rapids or rocks, a curragh can easily be picked up and carried over long portages. If the pioneers who dropped the arrowhead at Bridgend wanted to travel from the head of Loch Indaal to Loch Gruinart, a distance of less than two miles over flat terrain, they will simply have picked up their boat and carried it. If it rained on a voyage, the sailors could have put ashore and upended their boat to make an excellent shelter.

In 10,800 BC, hunters on an expedition, particularly one into the unknown, will have been properly equipped and dressed. And they would have been no rabble of ragged savages wrapped up in furry pelts roughly tied around the middle. All of the evidence suggests that prehistoric hunters wore and carried sophisticated gear adapted to the conditions and which they could maintain and repair as they moved through the landscape. Archaeologists have found needles at sites in the Refuges in southern France and these date to around 17,000 BC. Even earlier awls have been discovered and these sharp-pointed instruments, often made from bone, were used for making holes in hides so that they could be shaped and laced together. If hunters needed to move quickly or quietly through the wildwood in pursuit of prey, they will have worn close-fitting and well-made clothes which would not have hampered movement.

In a glacier high in the Alps near the border between Italy and Austria, a mummy was found almost perfectly preserved in the ice. In September 1991, two German tourists from Nuremberg, Erika and Helmut Simon, at first thought they had found a modern corpse. Eventually nicknamed Ötzi, the body was, in fact, dated to around 3,300 BC and, amazingly, much of the man’s clothing and equipment had survived for more than 5,000 years. He had been killed in a violent manner, probably by a blow to the head, and his forearm was freeze-framed in a protective position across his neck and face. Very soon after he was left for dead, the ice buried him.

Ötzi will have looked much like the hunters of the previous seven millennia. The only item found on his body not available to the pioneers who came to Islay in 10,800 BC was a copper axe head hafted to a yew handle. To keep him dry, Ötzi wore a cloak made from woven grass. This was not the stuff munched by cows and sheep but tough marsh grass which grows in spiky clumps in wet places. The design of the cloak is ingenious. The thick green stalks were tied in small bunches and laid over each other in a regular overlapping pattern like sheaves of thatch on a cottage roof. The cloak would have been light, waterproof, easily packed away and equally easily repaired. Ötzi may also have used it as a shelter or a sleeping mat.

Some evidence of aesthetics was found. Ötzi’s coat was designed and made as much for looks as utility. Reaching down to his knees and with long sleeves, it was sewn together with the fur side out and in strips of differently coloured pelts deliberately alternated light and dark. The coat was tightly belted because it was worn next to the skin and not over any garment resembling a shirt or an under-tunic. Fabric weaving waited in the future. On his lower body, Ötzi wore a leather loincloth and buckskin leggings up to his thighs. And on his head sat a thick bearskin cap with leather chinstraps to keep it secure in the winter winds of the high Alps.

To allow him to move safely and reasonably speedily though the snowdrifts, Ötzi may have been wearing snowshoes at the time of his death. Beautifully made (perhaps by a specialist cobbler, according to one scholar) from different skins, his shoes were waterproof and had wide soles made from thick bearskin. Softer deer hide was used to form the uppers and inside was a netting of tree bark to fit the wide shoes more closely to his feet and, to keep them warm, soft grasses were packed in, like organic socks. Near Ötzi’s body, part of a wooden frame and some hide were found and it has been convincingly argued that these were the remains of a snowshoe.

In a pouch sewn with sinew to his belt, the ancient huntsman carried a sharp bone awl, a flint scraper, a drill, flint flakes and a dried fungus. In addition to his copper axe Ötzi had a flint knife attached to an ash handle, a quiver of fourteen arrows, a bow string, an antler tool for making arrow points and a yew longbow of almost two metres. Most intriguing was what may have been a prehistoric first aid kit. Threaded on to a leather thong were two species of dried fungus and one of these, the birch bark fungus, is known to have antibacterial properties. The other was used for starting a fire. Along with other dried mosses and plants, it would take a spark struck from a flint against pyrite.

This most remarkable discovery opens a window on the life and style of prehistoric hunter-gatherers. The overall impression is of a gritty self-sufficiency. Not only could Ötzi repair his clothes, make flint arrowheads and start a fire, he could also treat an injury.

When forensic pathologists examined the mummified body, they were able to add even more to the story of the physical remains. Ötzi had stood 5 ft, 5 ins tall and was around forty-five years old. His bones suggested an arduous life of walking over hilly terrain. He may have been a shepherd as well as a huntsman. In his alimentary canal were two partly digested meals of chamois and red deer meat, eaten along with some wild roots and fruits and some cultivated wheat and barley. The latter would not have been available to the Islay pioneers and may well be the residue of bread.

When Ötzi’s mtDNA was sequenced, there were surprises. Isotope analysis had already concluded that he was born and raised in the Val Venosta in the Ötztal Alps, near where he died. Six modern inhabitants of the area were found to have inherited his mtDNA or at least the mtDNA lineage of his mother, given the inheritance pattern through the female line, a particular K1 type. But four other descendants show how very far travelled his lineage was, despite its extreme rarity. Matches turned up in Greece, Russia, Norway – and Scotland.

Pollen grains suggested that Ötzi had met his sudden death in the spring. An arrowhead was lodged in his left shoulder and there was a matching entry tear in his coat. Researchers also found evidence of cuts and bruises to his hands, arms and chest as well as the fatal blow to his head. It seems that, on the snowbound Alpine pass, Ötzi was brought down by an arrow and then bludgeoned to death by his pursuers.

No such archaeological drama was left by the hunters who came to the Rinns of Islay in 10,800 BC. In fact, the survival of any trace of their visit is close to miraculous for drama of another sort was waiting. Around 9,400 BC Scotland began once more to grow cold.

Thousands of miles to the west, in northern Canada, a disaster was about to engulf all who stood in its path. As the ice sheets slowly retreated over the North American landmass, a vast lake of intensely cold freshwater built up over much of what is now Canada. It covered an area much larger than the North Sea. At first, it drained slowly over a rocky ridge to the south, shaping the Mississippi river system, flowing ultimately into the Gulf of Mexico. But, as temperatures continued to rise, the ice dams to the west of the huge lake suddenly collapsed. With a tremendous roar, it broke through into the Mackenzie river system of northern Canada and, in a matter of only thirty-six hours, millions of cubic kilometres of cold freshwater gushed out into the Arctic and from there into the North Atlantic. The effect was catastrophic.

Almost instantaneously the Earth’s sea levels rose by a staggering 3 metres. Tsunamis surged towards helpless and unsuspecting coastlines and countless communities were swept into oblivion. But even more devastating was the dilution of the ocean with an enormous cubic tonnage of very cold freshwater. The Atlantic conveyor belt of ocean circulation, which carried the warming waters of the Gulf Stream northwards, was stopped dead. The climate suddenly changed. Over Scotland and northern Europe storms blew once more, snow fell steadily and did not melt with the coming of summer. A vast ice dome formed over Ben Lomond, the bitter cold crept back over the land and the pioneer bands fled south.

For more than a thousand years the Drumalban Mountains lay under the crushing weight of a dense ice sheet and the rest of Scotland withered into an Arctic tundra. Freezing winds and nine-month winters made settlement impossible but a brief summer melt might have allowed the growth of grazing and encouraged seasonal animal migration and perhaps hunting expeditions. Over fifty generations, stories and knowledge of the buried lands of the north might have been told and retold in the circle of firelight. Perhaps Scotland was not entirely lost in the endless snows and storms.

Eventually, the waters of the great Canadian lake were dispersed, the Atlantic Ocean regained its salinity and the conveyor system brought the Gulf Stream back to northern latitudes. Very quickly, over perhaps a decade, temperatures rose once more and the summer hunters gradually became pioneer settlers. At last, Scotland had finally emerged from the ice.

Very early evidence of the arrival of pioneer bands of hunter-gatherer-fishers was found by chance at Alaterva, the Roman fort at Caer Amon, the early names of the well-set Edinburgh suburb of Cramond. One weekend in the summer of 1999, a team of amateur archaeologists were digging an exploratory trench near the site of the bathhouse used by the soldiers stationed at Alaterva. Instead of an altar inscribed in Latin or some discarded military gear, they came across material that turned out to be almost 9,000 years older. At the bottom of the trench they carefully scraped away the earth around a deposit of flint tools and debris and a few hazelnut shells. For nine millennia these objects had lain unseen and untouched and it was the shells that allowed them to be securely dated. Hazel trees produce only one crop of nuts per year and this organic matter can be carbon dated. And it was reckoned that the six shells analysed had been cracked open some time between 8,600 BC and 8,200 BC. These were the earliest traces yet found of the first people to come to Scotland after the ice.

They chose the site of their camp well. Pitched on high ground near the outfall of the little River Almond into the Firth of Forth, it was surrounded by enough reliable resources to sustain year-round living. In the summer, the hinterland, now covered by Edinburgh’s western suburbs, would have made a good hunting ground. In the wildwood and its clearings, deer browsed and the giant cattle known as the aurochs thrashed through the undergrowth. More dangerous were boar and bears but there were many smaller animals to be trapped and birds could be netted. And summer roots, fruits, berries and nuts ripened in the late summer and autumn. The Cramond pioneers would have come to know exactly where the most heavily laden trees and bushes were and when each was in season. Hazelnuts were particularly prized because they could be roasted, mashed into a nutritious paste and preserved through the hungry months of the winter. The wildwood was also the provider of perhaps the most valuable resource – firewood.

The River Almond supplied freshwater fish and, since it is tidal in its lower reaches, the pioneers at Cramond may have built fish traps. Known as yairs in Scots, they were woven out of willow withies and staked in a line across the river. Having been careful to make the gauge of the weave wide enough to allow a free flow of water but too narrow for a fish to swim through, the fishermen waited for high tide. Coming in from the Forth to feed in the river, fish could swim over the top of the yairs. But when the tide ebbed and the level of the river dropped, they were often caught behind the mesh of withies. The bone tips of leisters, or fish spears, have been found at several early prehistoric sites and they would have been put to good use at the mouth of the Almond. At low tide, there were other good things to be had near at hand.

Along the unusually wide and gently shelving foreshore that reached out and beyond Cramond Island, there were rich oyster and mussel beds. These were still being harvested in the eighteenth century. In 8,600 BC, this resource in particular was vital because it provided fresh, protein-rich food throughout the winter.

Up on the bluff above the river mouth, where the Roman engineers would mark out the walls and streets of their fortress in the second century AD, archaeologists found faint traces of waste pits, scoops and stake holes dug by the pioneers some time around 8,500 BC. It appears that at Cramond they lived in structures resembling bender tents. Using principles similar to those of curragh building, whippy green rods were driven into the soil and tied with cords before a hide membrane was pulled over and made taut. Perhaps fat and resin were smeared over to make the shelter waterproof and turf laid over it for extra insulation against the winter winds. Fur pelts laid over cut brackens would have made a snug enough place to sleep.

No bones or burials or any physical remains of these early Scots have survived but DNA, archaeology and logic leave little doubt as to where they came from.

We are all, of course, descended from southerners, even those who live in Shetland, Iceland, Lapland and the very farthest extent of human settlement in the north. The ice and the direction of its retreat make that assumption unarguable. But DNA supplies more detail, more colour and unexpected connections. In addition to the M284 marker, another lineage found its way to Scotland from the Ice Age Refuges and the painted caves in southern France and northern Spain. M26 accounts for only 12,000 or so Scots men, around 0.5 per cent of the total population, and it is one of the oldest lineages still to be found. Other markers no doubt died out but it is likely that a substantial group of modern Scots are the direct descendants of the first pioneer bands who came north after the ice. Perhaps those who fished and hunted near Cramond had the M26 marker and, if so, then some of their descendants have not moved far. There is a scattering of addresses across the central belt of Scotland amongst the modern sample.

The M26 marker also moved eastwards from the Ice Age Refuges and it is the founding lineage of Sardinia and carried by an astonishing 40 per cent of the male inhabitants of the Barbagia, the mountainous central region of the island. There is a very tenuous architectural link with Scotland. On the rocky outcrops and ridges of the Barbagia stand the enigmatic drystane towers known as the Nuraghe. There are 8,000 of them and they closely resemble the famous brochs of northern Scotland. The difficulty with the connection is chronological – the Nuraghe were built from a very early date, 7,000 BC, and the brochs much later, in the first century BC and the first century AD – but it is not impossible. Historians believe that the particular skills needed to construct brochs and the speed with which so many appeared over a short period in Scotland may mean that specialist crews hired themselves out to powerful men who wanted such an obvious status symbol in the landscape. Perhaps the broch builders brought their technology and their DNA with them from Sardinia. In any event Scots with the M26 marker are more closely related to the men of the Barbagia in the male line than they are to other Scots.

Mitochondrial DNA is much more difficult to track than Y lineages. Its various types are much more evenly widespread in Europe and it appears that, while men tended to live and die where they were born (until very recently), women moved around a great deal more. This has caused a highly complex mix and wide spread of mother lines in contrast to a fairly straightforward stranding of father lines.

There is a brutal history lesson behind these DNA patterns. The enormous modern improvement in the status of women in Western society sometimes causes us to forget that, throughout the vast sweep of our history, women had little or no status at all. Leaving aside a few famous, mostly royal, exceptions, daughters, wives and sisters were treated like human property. Men almost always inherited wealth and land, which encouraged them to stay put, while women had to move away when and if marriage partners could be found. And women were also traded as virtual or actual slaves. In 697, at the Synod of Birr in central Ireland, the great Dark Ages churchman, St Adomnán, promulgated his Law of the Innocents. Amongst other measures it proposed protection for women who had long suffered as cumalaich, ‘little slaves’.

Probably the oldest Y lineage in Scotland leads the eye eastwards rather than due south to the caves of France and Spain. M423 has a similar frequency to M26 with around 20,000 Scots men carrying the marker and it is another founding lineage. Remarkably it is shared by between 30 per cent and 40 per cent of Croatian and Bosnian men and appears to have originated in the Danube basin. This was one of the points of entry into Europe for the pioneering bands who left the rift valleys of Africa and came north through Mesopotamia. A subgroup of the M423 lineage appears at the western end of the North German Plain and then reappears on the British shores of the North Sea. It is as though there is a missing historical step.

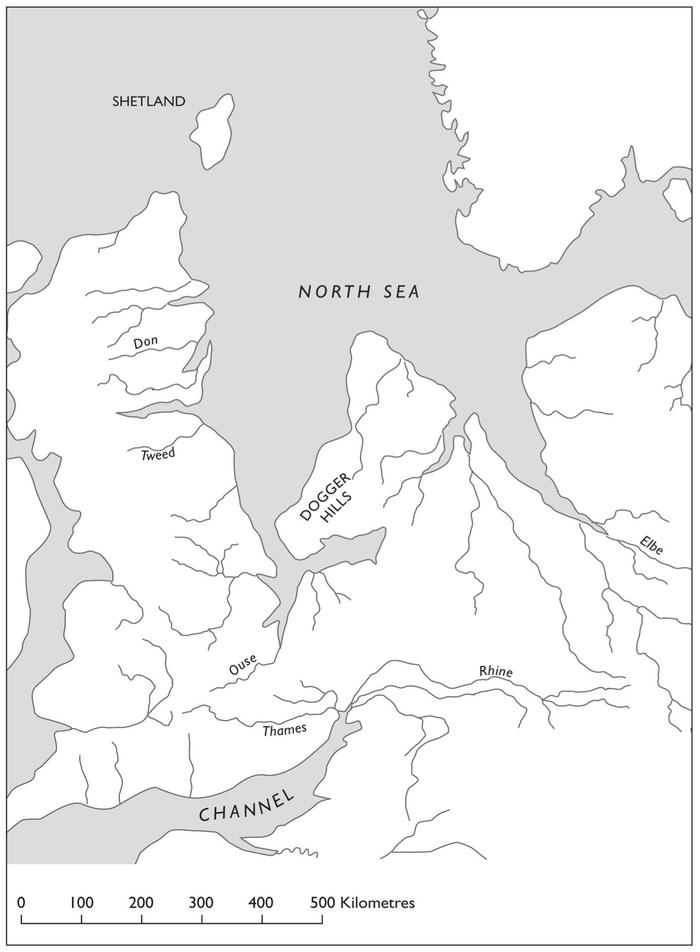

In early 2001, researchers at Birmingham University looked at a dim, grainy image and were amazed at what they could make out. Picked out in green and yellow against a black background was the course of an ancient and unknown river. Fed by a network of tributaries, it seemed to run for about thirty miles. The disappeared river had been found by seismic reflection, a version of the geophysical surveys done by archaeologists on sites where the remains of buildings or earthworks are thought to be buried. But the green images were different. Supplied by the oil and gas industry, they were part of a vast survey of the bed of the North Sea and what lay under it. The ancient river had once flowed through the hills and valleys of a lost world, a huge part of Europe which had disappeared beneath the waves and been entirely forgotten.

Doggerland is the name given to the lost continent now covered by the North Sea and which linked the British Isles with continental Europe. The map shows Doggerland in the earlier Holocene period, with extensive coast and estuaries.

At the zenith of the last Ice Age when bitter hurricanes tore down from the summits of the spherical domes, northern Europe was crushed. Under the great weight of cubic kilometres of ice, the crust of the Earth had been depressed so much in the north that the land to the south had risen. Like a fat man sitting on one end of a bolster, the ice had produced an effect called a ‘forebulge’. And so, when the ice retreated, a vast subcontinent was revealed. It was Europe’s lost subcontinent, an Atlantis in the east.

To the north of the Shetland Isles, there was dry land and it was only separated from Norway by a deep undersea valley known as the Storegga Trench. In the centuries immediately following the end of the Ice Age, the subcontinent covered almost all of what is now the North Sea and there was no English Channel in the south. The great rivers, the Tweed, Tyne, Elbe and Weser, flowed north into the Storrega Trench while the Thames and the Rhine combined into the Channel River which made its way westwards to the Atlantic. What the Birmingham researchers could make out in the greens and yellows of the seismic reflection image was a prehistoric river which ran eastwards, near what is now the Dogger Bank.

Long before the oil and gas companies began to map the bed of the North Sea, those who lived on its coasts knew that some land had been submerged. At low tide, blackened and clearly ancient tree trunks would appear, often stretching far out to sea. These were known as Noah’s Woods and were seen as certain evidence for the great biblical flood. Oyster dredgers had brought up animal bones and clods of a peaty soil called moorlog. Archaeologists had conjectured the existence of a landmass rather than a mere land bridge linking Britain to Europe and, after the famous sandbank, they named it Doggerland.

What the seismic reflection survey supplied was not only confirmation but detail. Much of Doggerland was an immense and watery plain. Many lost rivers meandered through it creating oxbows, wide deltas and large areas of wetland. Some of these flowed into a huge inland sea, what the undersea surveyors called the Outer Silver Pit. The Dogger Hills were a rare area of high ground. In the samples of moorlog brought to the surface for analysis, pollen traces have confirmed birch, willow, hazel, oak and chestnut trees. It is thought that deer, boar, bears, beavers and many other animals browsed the lush vegetation of the Doggerland woods while its wetland will have been home to many species of birds. For hunter-gatherer-fishers it was a very good place to live. But only the faintest, most shadowy traces of people have been found.

On a September night in 1931, Captain Pilgrim Lockwood guided his fishing trawler, the Colinda, out of Lowestoft Harbour. Twenty-five miles off the Norfolk coast, by the Leman and Ower Banks, Lockwood had his crew haul in the nets. Amongst the silver glint of fish was a dark lump of moorlog. The skipper pulled it on to the deck so that he could break it up with a shovel and heave the bits over the side.

We were halfway between the two north buoys in mid-channel between the Leman and Ower … I heard the shovel strike something. I thought it was steel. I bent down and took it below. It lay in the middle of the block which was about 4 feet square and 3 feet deep. I wiped it clean and saw an object quite black.

It was a spear point. More than 21 cm long and made not from metal but antler bone, this beautiful object had been skilfully worked into a sharp point with one edge precisely serrated so that it would lodge securely in the flesh of its target. One end was scored with transverse lines to enable a good fixture to a wooden shaft. Pilgrim Lockwood had clashed his shovel on what was almost certainly the tip of a leister, a fish spear. Everything about this fine object spoke of people, of manual skill, of food gathering, of someone hunched over the antler point fashioning it and lashing it to as straight a cut branch of ash or oak as they could find in the wildwoods of Doggerland.

More extraordinary was the find-spot. The Colinda had been trawling 25 miles off the Norfolk coast and the bone point had been buried in a large lump of what sailors call ‘moorlog’ (submarine peat), making it unlikely that the leister had been dropped over the side of a boat. Carbon dating placed it deep in prehistory. Lockwood had picked up something made by a hunter-fisherman in Doggerland some time around 11,700 BC.

For a generation what became misleadingly known as ‘the Colinda harpoon’ was all that had survived of the peoples of the lost subcontinent. But more physical evidence has gradually come to light. In the 1970s, a Dutch archaeologist, Louwe Kooijmans, wrote up reports of a series of bone tools which had been brought up from the bed of the North Sea. This time the find-spots were to the south of the Leman and Ower, at the Brown Banks, where the sea narrows between the Belgian and Suffolk coasts. Divers from Newcastle University have recently found more remnants of the Doggerland people off the Northumberland coast, near the mouth of the Tyne.

From the time that the ice in the north began to retreat, around the period when the hunter-fisherman was carefully carving the serrated notches on his leister point, Doggerland was doomed to drown. As the great weight of the huge ice dome over Norway and Sweden diminished and eventually disappeared, the newly revealed land began to rise and what was to become the North Sea began to sink. It was a gradual process perhaps punctuated by occasional local dramas as the sea broke through and made tidal islands of higher ground, creating salt marshes, sometimes making freshwater lakes brackish. For five millennia, the hunters of Doggerland trapped, netted and speared the rich fauna and gathered the abundant fruits, roots and nuts of the fertile plains. But it was to come to end more emphatically than anyone imagined. Around 6,000 BC, geology forced history to accelerate and, in an instant, the world changed.

In the freezing darkness of the Storegga Trench, two thousand feet below the surface of the North Sea, the bottom feeders sensed an unknowable danger. Above them sharks, whales and wolf fish instinctively swam upwards when the seabed began to quiver and stray rocks suddenly tumbled through the wrack. Dust darkened the water even more as small marine creatures panicked and scattered. And then the undersea world disintegrated. Seismic movement in the Earth’s crust caused 3,400 cubic kilometres of rock, gravel and sand to slip into the deeps of the great trench. Along a 290 km length of coastal shelf, an area the size of Scotland broke off and collapsed. The momentary gap sucked in vast quantities of seawater and set in train a rapid and devastating chain of events.

Around the coasts of eastern Scotland, Norway, Denmark and northern Doggerland, the sea retreated rapidly, revealing huge tracts of the seabed. At first, there must have been astonishment on the faces of all who saw it. Perhaps the world was ending, perhaps the gods were angry. Then seabirds suddenly shrieked and took to the air. A distant rumble was heard and, before many had the presence of mind to run for their lives, a gigantic, 8-metre-high tsunami roared on to the shore. Travelling at an incredible 600 miles an hour, it crashed over coastal communities, snapped trees like matchsticks and rained down boulders, debris and sand far inland.

No one saw this undersea earthquake begin and evidence was only discovered by accident when archaeologists exposed a mysterious layer of white, deep-sea sand on a dig in Inverness. Similar deposits have been found in Shetland, Orkney, the Montrose Basin, the Firth of Forth and up to 50 miles inland. But the most profound effects must have been seen in Doggerland. It is likely that most of the low-lying subcontinent was drowned and reduced to a large island around the Dogger Hills and four or five smaller survivors to the south. Britain was at last isolated from Europe and, within a thousand years of the great tsunami, Doggerland had disappeared beneath the waves. But its people did not.

Those Scots who carry the M423 marker are almost certainly descended from the survivors of Doggerland or at least those ancestors who walked across the great plains on their journey westwards from northern Germany. Alongside the M284 and M26 markers from the Ice Age Refuges on either side of the Pyrenees, the children of the drowned subcontinent form one of the three founding lineages of Scotland. In all, these groups number around 150,000 of the modern male population – they were the earliest immigrants, those who first set eyes on Scotland after the ice.

The pattern of mitochondrial DNA is different. It appears that most European (and Scottish) mtDNA is even older than the Y chromosome markers, some of it reaching back well before the last Ice Age to around 40,000 BC. This was the time when the first bands of Homo sapiens entered Europe on the long journey out of Africa. The oldest types belong to the U5 and U8 groups of mtDNA and it looks as though they spread north and east once more from the southern Refuges around 12,000 BC. A large group, around 6 per cent of Scots or 300,000, belongs to U5. The most common mtDNA group is labelled H and it accounts for nearly half of the population. Group H appears to have arrived in Europe just after the peak of the last Ice Age and its variants again show a dispersal across Europe from the Refuges. The subgroups H1 and H3 in particular radiate from what is now the Basque Country across the continent, having begun to move rather later, around 9,000 BC. The ability to tell definitively which mtDNA lineages are related to which has only recently been possible, as the costs of reading all of the 16,569 letters of the mtDNA code has reduced. For that reason, this data is very general and it must be unlikely that the only origin of Scottish mtDNA lies in the south. Until more research on a much larger scale is done, the picture will remain blurred and piecemeal.