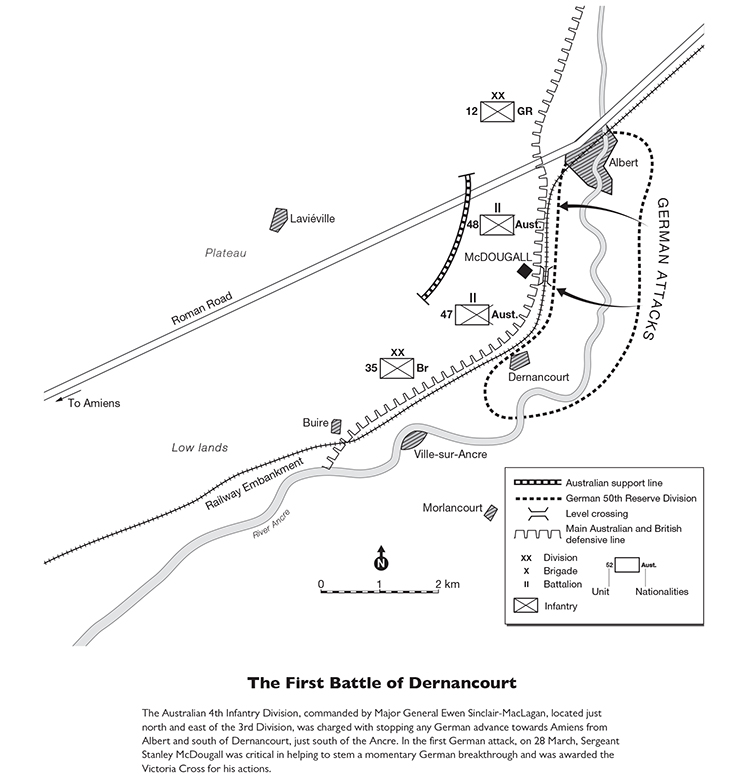

Meanwhile, just north of Monash’s division, Sinclair-MacLagan’s 12th and 13th brigades were moving towards Hénencourt, which overlooked the Amiens–Albert road. The brigades took up a position west of Albert in the vicinity of Warloy and during the morning of 27 March they had a well-deserved rest. They now occupied the old rear areas of the 1916 battlefields, just a few kilometres from the advancing Germans. No one knew what to expect. The position provided an excellent view of the city of Albert below, now in German hands and 5 kilometres east. At a similar distance south of Hénencourt lay the Ancre river and the village of Dernancourt. This was a critical position, as the British feared a German advance from the area around Albert to Amiens. However, the open ground west of Albert sloped up to the highland ‘plateau’ around Hénencourt and was exposed to artillery and machine-gun fire. The most likely German approach from this sector would be from the south, from Dernancourt, where the terrain along the river – more correctly described as a creek at this point – was intersected by a number of shallow gullies running north from the Ancre, providing an excellent approach to the heights.1

South of Dernancourt in the river valley were the little villages of Ville-sur-Ancre, Treux and Buire, surrounded by broad marshes – in some places as broad as 1500 metres. So far only Ville-sur-Ancre, on the southern bank of the river, lay in German hands. Buire was positioned about 4 kilometres west of Dernancourt on the northern bank, while Treux lay immediately opposite Buire on the southern side of the river. At Dernancourt the railway ran just north of the village, resulting in a railway cutting into the lower slopes that created a long embankment, while at Buire the railway embankment was located south of the town, between it and the river. From the river valley, several spurs defined by narrow gullies on either side thrust out from the railway, cutting along the south and eastern side of the Laviéville hilltop. A tactically critical spur, Laviéville Crest, ran from the hilltop to a cutting close to Dernancourt; this crest or hill would quickly become a major Australian defensive position. A railway bridge crossed the Dernancourt–Laviéville road just west of the town, and the road traversed Laviéville Crest on its way north to Laviéville. Located between the hill and Dernancourt was a stone quarry that provided a good defensive position covering the railway bridge and underpass.2

The northern railway embankment and cuttings of the Albert–Amiens railway, curving around the foot of the hills just north of Dernancourt that overlooked the village and the river, were currently held by the badly mauled British 9th (Scottish) and 35th divisions, each now the size of a small brigade. The village of Dernancourt itself was only lightly defended by British troops of the 35th Division. In reality, defending the railway embankment was not the best defensive plan. It would have been far better to occupy the strong position defined by the plateau that looked down on the spurs and gullies. But the orders for the Australians were that they were to hold the railway line and embankment.3

__________

By early morning 27 March, the 47th and 48th battalions of the 12th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier John Gellibrand, a 46-year-old orchardist from East Risdon in Tasmania, had arrived at Senlis and had a few hours’ rest before being ordered to Hénencourt. The remaining two battalions of the brigade, along with the 13th Brigade, were not far behind. Gellibrand was informed that the Germans were launching an attack on Dernancourt against the railway embankment, between the village and Albert. It was vital that this advance be halted. He was ordered to advance his two battalions down the open ground towards Albert to check the German advance from the south-east and relieve the hard-pressed and numerically depleted 9th Division holding this part of the line. These troops had been in action since 21 March and were exhausted and badly in need of rest and reorganisation.

Gellibrand’s two battalions advanced eastwards down the completely exposed slopes straight into German artillery fire with the 48th to the north and 47th to the south. Lieutenant Mitchell of the 48th Battalion later wrote:

Dead ahead across our path four big black shrapnel bursts. Hares started up by our formation were dashing madly in all directions. ‘Poor little blighters,’ we thought. ‘Hope they get through.’ A riderless horse galloped madly across the field, its flanks covered in blood . . . some [shells] landed among sections, and our track was now littered by little khaki heaps . . . as I looked through the rifts of flame and smoke there moved the [two] battalions, steady and unfaltering, their sections spread across the whole countryside. Sole survivors of sections kept their appointed places and speed. It was worth the price to be with such men.4

Where possible, men took cover for a quick breather within the shallow gullies cutting through the exposed plain. ‘Advance again,’ recalled Mitchell, ‘now skirmishing order, toward where the avenue of the Albert–Amiens road cut obliquely across our path. The hail of shells was redoubled, and complete sections were blown up. Bodies spun in the air like sacks of straw.’5

The men of the 47th Battalion advanced with their battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Imlay, a 33-year-old manager from Prospect in South Australia, who ordered them to use a sunken road to reach their objective: the railway embankment guarding the approach from the town and the river currently held by the exhausted Scots. The war diary of the 47th Battalion records that they suffered close to 100 casualties, including six officers, before making it to the embankment.6 To Imlay’s left, the commander of the 48th Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Raymond Leane, whose men also advanced down the slope, refused to move towards the embankment during daylight as his soldiers would suffer enfilade – he would wait until darkness. As recalled by Mitchell, ‘I found a four-foot [1.2-metre] drainage pit on the side of the Albert–Amiens road. The shells on the cobbles sent squalls of metal all over us. The lopped branches of the avenue kept falling round us.’7 Leane’s actions, while undoubtedly saving the lives of many of his men, potentially placed the 47th Battalion in great danger by leaving its left flank exposed to the Germans in Albert.

The sacrifice made by the men of these two battalions turned out to be in vain. There had been no German attack against Dernancourt – it was a false report. On eventually making its way south after dark, the 48th Battalion was thrown back sharply from the railway across the Amiens–Albert road to protect the left flank in front of Albert. Just to the north was the southern flank of the British 17th Division.8

Meanwhile, the two remaining battalions of the 12th Brigade, the 45th and 46th, had arrived. Gellibrand had set up his brigade headquarters at Laviéville and placed the 45th Battalion in support at Hénencourt. Here, 15 light whippet tanks were placed in Hénencourt Wood to help repulse any German break through; the artillery of the 9th Scottish Division was to remain in place until the Australian batteries arrived.9 The men of the 45th Battalion began to dig a support line, while the 46th Battalion was placed in reserve just west of Senlis, about 2 kilometres north. As recalled by Private Norman Pope (a 27-year-old farm labourer from Beechworth in Victoria), ‘Still in reserve up in the line last night carrying trench mortars to the line. Raining day and night, stolen sheep for tea.’10

It wasn’t long before the 13th Brigade, under the command of Brigadier William Glasgow, was positioned to act as a further blocking force against any German breakthrough from Albert towards Amiens. Glasgow’s 49th and 50th battalions were positioned on a north–south axis in front of Laviéville, while the 51st and 52nd battalions took up a similar position behind the town.11 The 13th Brigade was to take up its position along the heights around Hénencourt, as recalled by Private Alan Barber, a 30-year-old shearer from Pingelly in Western Australia with the 51st Battalion: ‘The village of Bresle lay to the right, hidden from sight in a valley. Roads led eastwards from the village and then turned south. This road was covered in military traffic. The German artillery had the road zeroed in. To dawdle was to invite death. Salvoes of shells burst on the road at intervals of a few seconds. The battalion advanced down the [southern] slope of the hill gradually moving over the right. Positions on the far side of the valley, near Bresle on the right, were taken up.’12

The British 35th Division still covered any German advance from the south by occupying the straight part of the railway embankment from Dernancourt to Buire, while the northward curve just east of Dernancourt towards German-held Albert was now occupied by the Australians of the 47th and 48th battalions.13 Earlier, with the arrival of these Australians, the few survivors of the 9th Division had finally been relieved. The bloodied, weary and shell-shocked men of the 11th Royal Scots and the 9th Seaforth Highlanders withdrew in the moonlight, waving and wishing the Australians well.14 Later that night Lieutenant Mitchell, after having posted a number of sentries, took up a position along the railway embankment, looking out beyond. He wrote: ‘Lord, it was quiet. Not a bullet. Not a shell. I could see a group of huts in front, and a river marked by trees. Over to the left was Albert, bathed in mist.’15

During the night, the men of the 4th Division set about building up their defensive works. A system of support trenches was dug about 300 metres behind the railway embankment and at the crest of a hill directly behind Dernancourt, halfway up the slope towards Millencourt along Laviéville crest, and a 2-metre-deep trench was under construction that bisected the Amiens–Albert road about 1.5 kilometres west of Albert. This was a strong defensive position, well sited with a commanding view of all approaches; when finished, the works would be christened ‘Pioneer Trench’. As had become standard practice, the Australian defence was ‘in depth’, with battalions placing two or three companies in the forward zone with another close by in support and another, sometimes from a brother battalion, nearby in reserve.16

That night the Germans of the Prussian 229th and 230th regiments made ready to storm across the level crossing just beyond Dernancourt with the aim of taking the high ground around Laviéville, which would not just leave Amiens further exposed to an infantry assault, but also provide perfect ground from which to shell the city and its vital railway hub. It would also force those covering the flanks of the Australian 4th Division to withdraw further west from fear of having their own flanks turned.17

__________

All British eyes were focused on Amiens. General Henry Rawlinson, who had just taken over command of the Fourth Army, after a conversation with General Gough recorded on the morning of 28 March that ‘the situation is serious. The V Army troops are beat to the world and no French reinforcements are yet in sight. If the Bosche [sic] attack heavily . . . I fear he will break our line of defence in front of Amiens and the place will fall.’18 A few days later he went further, declaring that the Amiens sector was the only one ‘in which the enemy can hope to gain such a success as to force the Allies to discuss terms of peace’.19

It was precisely this part of the line that was being held by the Australians of the 3rd and 4th divisions, and they had no such qualm. Indeed, Monash wrote to Birdwood at 10 a.m. on 28 March that he was ‘quite secure against all but an attack on a grand scale’. He further informed his CO that ‘my troops are in the highest sprits; my ammunition supply, about which I was anxious, is now on a fairly satisfactory basis; food and water are all right; one ambulance has arrived, and the others are in sight. By tonight I hope to have all departments thoroughly well organised. The men are, of course, very sleepy . . . but every hour that we are left unmolested is improving their condition.’20

__________

Just as dawn was breaking on 28 March, Sergeant Stanley McDougall, a 28-year-old blacksmith from Recherche in Tasmania, and two of his men of the Australian 47th Battalion were posted to watch the level railway crossing that overlooked the Ancre flats just opposite Dernancourt; they were positioned just north of the crossing. As McDougall peered through the rising mist he heard the sound of what he knew to be bayonet scabbards flapping against the thighs of marching troops. He woke his two men, whom he had allowed to get a moment’s shut-eye, and also called out a warning to Lieutenant George Reid, a 22-year-old labourer from Brisbane, and Lieutenant Ernest Robinson, a 32-year-old printer from Sydney, who had just passed them. McDougall bolted down the railway to warn the nearest outpost, but just as he did so a number of Germans emerged from the mist, quickly followed by several grenades thrown over the embankment; one exploded among a Lewis gun crew. Without hesitation McDougall turned and picked up the Lewis gun, hoping against hope that it was still working. He squeezed the trigger and it sprayed a hail of bullets, killing a number of Germans, including two light machine-gun teams who were crossing the embankment.21

McDougall now discovered a number of Germans preparing to attack from a shell hole near the embankment and opened fire again, scattering the survivors. During this attack his Lewis gun was damaged by German fire, but he found another. On turning around, he found that other Germans had penetrated the line and were getting behind his battalion. He stopped their advance with bursts of machine-gun fire and continued to pour fire into several Germans who had infiltrated the Australian lines. But soon his hand was burnt from holding the red-hot barrel of the Lewis gun. Sergeant James Lawrence, a 30-year-old station manager from Townsville in Queensland, came to his aid and, wearing gloves, held the barrel of the machine gun while McDougall squeezed the trigger and with his burnt hands changed the magazine drum. Meanwhile, just north of the level crossing, lieutenants Reid and Robinson had organised a counterattack and opened concentrated enfilade against the mass of Germans trying to cross the level crossing.22

Now a full-on attack was being launched against the 12th Brigade’s front from Dernancourt to just south of Albert. However, as more Germans tried to bridge the Ancre in support, they were cut down by enfilade from the men of the 48th Battalion just north of the level crossing and the British troops of the 19th Northumberland Fusiliers (35th Division) to the south. Indeed, the Australians of the 48th Battalion appeared insulted by the appalling lack of tactics in the mass frontal assault against their position. ‘They did not attack, they simply advanced,’ wrote the battalion’s historian. ‘Never before in the course of the war had Australian soldiers seemed to be treated with contempt by the enemy, and the diggers felt honestly puzzled as they swept the oncoming Germans with rifle and machine-gun [fire].’23 It was Hébuterne all over again.

In all, nine attacks were launched by the Germans that day against the British and Australian positions along the railway embankment, but all were repulsed; the Germans suffered over 500 casualties. As described in the war diary of the 12th Brigade, ‘All attacks made by the enemy were repulsed with heavy losses, and Machine Guns and Lewis Guns and Riflemen were busy all day operating against wonderful targets.’24 The few Germans who managed to traverse the railway crossing and remain alive were captured by McDougall and others. Sergeant Stanley McDougall was awarded the VC for his actions that day.25

However, the Germans had occupied the village of Dernancourt in strength. A frontal assault by the British 19th Northumberland Fusiliers (35th Division) was ordered to retake it. The Australians of the 47th Battalion were to act in support, extending their line to cover the embankment vacated by the British and being prepared to advance into the town itself to help exploit any successes of the British. One company of the 45th Battalion was also to move south from the plateau to support the 47th Battalion at the railway embankment.26 As these men moved out over open ground heading south, they were met with a hail of enemy fire. Lieutenant Mitchell recalled that ‘bars of splattering machine-gun bullets lay across their path. Shells hounded them all the way. Men fell at regular intervals. Their mates would kneel to inspect the fallen, do something for them, or pass on with a strange revealing gesture of finality. Steadily they moved to their rendezvous with death.’27 In this desperate charge, ‘B’ Company suffered 50 per cent casualties: one officer and around 40 other ranks.28 Strangely, the published battalion history makes no reference to this sacrifice, merely stating that during the battle the men began to ‘dig a support line’.29 The attack by the British troops resulted in predictable slaughter and was soon followed by a ‘propping attack’ by the men of the 47th Battalion. Again nothing was achieved except an increased body count.30

__________

A number of German prisoners were interrogated by the Australians that night: what was their objective? The repeated answer to this obvious question was revealing about the overall German grand strategy: ‘the answer came that they had no objective. They were simply to march towards Amiens, when they were tired other troops following on motor lorries should take their place and continue the march. They themselves had been brought to the vicinity of Albert on the proceeding night by motor lorries, they had a drink of coffee in Albert at 3 o’clock that morning and at 5 o’clock started on their forward march.’31 If nothing else, Ludendorff could be taken at his word: ‘merely set an intermediate objective, and then discover where to go next.’