Deciphering Bridge Gibberish and Other Bridge Commentary

by Syd Fox

The kind of bridge you have read about is known as duplicate bridge, because in effect, the hands are duplicated. Everybody plays the same hands. This makes the luck of the cards much less of a factor.

The other type of bridge is known as rubber bridge or party bridge. It simply involves four people sitting around a table, shuffling and dealing after each hand. They talk and laugh and have a good time, and it's no big deal if somebody forgets the contract or whose turn it is to play a card.

Such perfectly normal social behavior drives duplicate players up the wall! We don't want to hear about Aunt Mabel's hip operation, or what somebody's precious child said to her second-grade teacher. To us, it's all about the cards.

Over the years I've played against people from all walks of life; young and old, rich and poor, Nobel Prize winners and construction workers, professional athletes and people who are physically disabled, famous actors and politicians. I've even sat at a table with two men who told me they had learned the game while in prison.

If you're interested in becoming a part of this amazing game, you can find out more atwww.acbl.org. When you first get started, don't worry if you don't know a lot of complicated bidding systems or defensive signals. You will have plenty of other things to think about. Go ahead and make the logical bid or just the one that feels right . If an opponent asks what a bid means, or what kind of defensive signals you use, you can simply say, "We have no agreements." You and your partner are allowed to have no agreements. You're just not allowed to have any secret agreements.

As you become more experienced, however, you will find that these kinds of agreements are useful. Bridge is a partnership game, and the more you and your partner can cooperate, the more fun you will have and the better you will play.

I hope to meet you at the table someday.

A Note on the Scoring

Some eagle-eyed reader will no doubt notice that, Trapp's opponents scored 420 points for making a four-spade contract. Then, Gloria also made four spades, but got 620 points. There are other apparent scoring discrepancies as well.

These are not errors. It has to do with something called being vulnerable.

Just as the board indicates who is the designated dealer for each hand, it also indicates which side is vulnerable. On board number one, nobody is vulnerable. On board two, North-South is vulnerable. On board three, East-West is vulnerable. On board four, both sides are vulnerable.

If you're vulnerable and go down in a contract, you lose 100 points per trick. If you are nonvulnerable, you only lose 50 per trick. You get a bonus of 500 points for bidding and making game when vulnerable, and only 300 when nonvulnerable. You also get bigger bonuses for slams when vulnerable.

Duplicate players will often take the vulnerability into consideration when deciding whether to bid or pass.

Running Commentary

Page 18:

There were two parts to a bridge hand, the bidding and the play. …

There's also a third part, the post-mortem. That's when you try to justify all the mistakes you just made, or better yet, blame them on your partner.

Part 21, the "Are you sure?" hand:

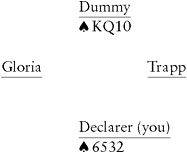

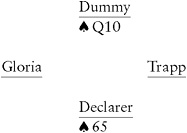

This was the spade situation described in Trapp's rant:

Put yourself in the declarer's shoes. You lead the  2. Gloria plays a small spade. You play the

2. Gloria plays a small spade. You play the  K from dummy, and Trapp plays the

K from dummy, and Trapp plays the  4.

4.

Now you return to your hand in another suit, and lead the  3. Again, Gloria plays a small spade. What card do you play from dummy?

3. Again, Gloria plays a small spade. What card do you play from dummy?

There's no easy answer. It all depends on the location of the  A and

A and  J. If Gloria has the

J. If Gloria has the  A and Trapp has the

A and Trapp has the  J, you should play dummy's queen. On the other hand (pun intended), if Gloria has the

J, you should play dummy's queen. On the other hand (pun intended), if Gloria has the  J and Trapp has the

J and Trapp has the  A, you should play dummy's ten.

A, you should play dummy's ten.

How do you know? You don't.

Except earlier, when Trapp told Toni to play the  4, she asked, "Are you sure?"

4, she asked, "Are you sure?"

Now you know Trapp has the ace, so you play dummy's  10.

10.

This is what had Trapp so steamed. It was why he and Toni got into a fight, and why Alton became his new cardturner.

Page 26:

"I'm the only one to bid the grand, which would be cold if spades weren't five-one."

"Unless you can count thirteen tricks, don't bid a grand."

"I had thirteen tricks! Hell, I had fifteen tricks, as long as spades broke decently."

That last comment was a joke. You can never take more than thirteen tricks. Bidding a grand means bidding a grand slam. The speaker claimed he would have made it if the spades had been divided more evenly between his opponents.

If you are missing six cards in a suit, they will divide 5-1 or worse only about 16 percent of the time. So it does sound like bad luck, not bad bidding.

Page 26:

"Trapp!" she demanded. "One banana, pass, pass, two no-trump. Is that unusual?"

It sounded unusual to me.

"That's not how I play it," said my uncle.

You can't bid one banana. It isn't a suit. "One banana" simply means the bid of any suit except no-trump. One spade, one heart, one diamond, or one club—it doesn't matter.

"Is that unusual?" refers to a common bidding convention used by most duplicate bridge players, called the unusual two no-trump bid.

The unusual two no-trump bid is usually made directly after an opponent bids. Most commonly it shows the two lowest-ranked unbid suits.

So if an opponent opens the bidding with one heart and you bid two no-trump, you're telling your partner you have a hand with at least five clubs and at least five diamonds. If an opponent opens the bidding with one diamond, a bid of two no-trump would show five hearts and five clubs.

In the situation described here, the bid of two no-trump isn't made directly after the bid. There are two passes in between.

One banana—pass—pass—two no-trump.

Trapp indicated he would not take that as "unusual," and neither would I. In this instance, it would be the "usual" two no-trump bid, showing about twenty points including one or two high bananas.

Page 28:

She was nicely dressed, as were most of the women in the room. It was mostly the men who were slobs.

I have a theory about that. Bridge requires such a high degree of concentration, you want to be comfortable so as not to have to think about anything else. Women feel comfortable when they're confident about the way they look. Men feel comfortable when they're … well, when we're comfortable.

Not every man, and not every woman, of course, but it occurs often enough for Alton to have noticed.

Page 32, the skip:

It was like some sort of odd dance, with the people moving in one direction and the boards moving in the other. After the seventh round, every East-West pair skipped a table to avoid playing boards they had already played.

When there is an even number of tables (fourteen, in this case), a skip is needed to avoid playing the same boards twice. If there is an odd number of tables, no skip is necessary.

Pages 40-41:

One time it lurched a bit, and almost died, but I doubted Trapp noticed. We were driving back to his house after the Wednesday game, so his mind was on some bridge hand.

He would think not only about what he should have done differently, but also about what the opponents should have done, and what he would have done if they had done that. I could have driven into a ditch and he wouldn't have noticed.

Bridge players are famous for getting lost in their thoughts, especially when driving. Once after a tournament I drove forty-five miles past my exit before I finally looked around and thought, "Where am I?"

Page 69:

"Aces and spaces …"

"I had nine points, but it was all quacks… ."

"Odd-even discards?"

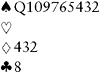

You often hear bridge players complain about aces and spaces. An example would be a hand like this:

Notice all the space between the ace and the next-highest card in that suit. True, a ten or a nine would be nice, but I like aces too much to ever complain about the spaces.

A quack is a queen or a jack. Nine points refers to the hand evaluation system that Toni taught to Alton. Charles Goren developed this system over fifty years ago, and while it's still used today, most experts agree it is not entirely accurate. Aces and kings are slightly undervalued, and queens and jacks, or quacks, are slightly overvalued.

Odd-even discards refers to a type of defensive signal. If a defender discards an odd card (3, 5, 7, or 9), it means she wants her partner to lead that suit. For example, if she discards the  5, she's asking her partner to lead a diamond the next time he gets a chance. If she discards an even card, the

5, she's asking her partner to lead a diamond the next time he gets a chance. If she discards an even card, the  4 for example, she's telling her partner she doesn't like diamonds.

4 for example, she's telling her partner she doesn't like diamonds.

The problem with this system is that sometimes you only have even cards in suits you like and odd cards in suits you don't like.

Page 81:

If you double, you're saying you think your opponents bid too high. If they make their contract, they'll get double the points, but if you set them, then you'll get double the points.

It's more complicated than that, but the general idea is correct.

The chart below shows how many points you get for setting a contract doubled or undoubled. The vulnerability applies to the side that bid the contract, not the side that doubled it.

I stopped the chart after down-seven, but you can actually go down as many as thirteen tricks on a hand (if you bid a grand and don't take any tricks). If you're wondering if any idiot actually has gone down as many seven tricks on one hand, yes, I have.

Page 90, Yarborough:

The odds of being dealt a Yarborough (no card higher than a nine) are 1,827 to one.

Page 97:

"Bidding's not that hard, once you learn the basics. Trapp and Gloria use a complicated system, but you don't have to do all that. You just have to know which bids are game-forcing, which ones are invitational, and which ones are just cooperative."

Using the Goren point-count system, you should bid game if you and your partner have a total of 26 points. So if your partner opens the bidding (promising at least 13 points), and you have 13 points in your hand, you know you belong in game. Your partner, however, doesn't know this, and it's your job to let him in on the secret.

A game-forcing bid is one that tells your partner, "I want to bid game on this hand, so you must not pass until we have done so."

An invitational bid is one that invites game. Again, your partner made an opening bid, but this time you have about 10 to 12 points. You'll make a bid that invites your partner to bid game if she has a little extra.

A cooperative bid shows about 6 to 9 points. Your partner opened the bidding, and you have too many points to pass, but you're not interested in bidding game unless she has a lot extra.

There are many different bidding situations, but the key to good bidding is understanding whether a bid that you or your partner makes is game-forcing, invitational, or cooperative.

Page 125:

"After going into the tank for ten minutes, he leads a club, giving the declarer a sluff and a ruff! Then, in the postmortem, he asks me if there was something he could have done differently. ‘Yes,' I tell him. ‘Play any other card.' "

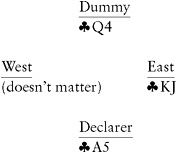

To go into the tank means to think for a long time before playing a card or making a bid. To ruff means to win a trick by playing a trump. To sluff means to discard. A sluff and a ruff occurs when a defender leads a suit in which both declarer and dummy are void, and where both hands have trump cards. It allows a declarer to ruff in one hand and to discard in the other, often giving her an extra trick. For example:

Spades are trump. It looks like you have to lose a club trick, but if an opponent leads a heart, you will get a sluff and a ruff. You can discard a club from one hand and trump it in the other. This will allow you to win all the rest of the tricks. (Try it!)

Page 137:

The directors had a very specific rule for each situation. So not only were these mistakes really dumb, I realized, but they all had happened many times before.

And I've made every single one of them.

Page 159, the two idiots at table seven:

It was around this point that I noticed the blond guy squirming in his chair. When Toni won the next trick, the bushy-haired guy started squirming too.

If you see an opponent squirm, that's always a tip-off that he's being squeezed. If you're ever in such a situation, try not to squirm. Try to decide on your discards before it's your turn to play, and then calmly play as if you don't have any problem. Often a declarer won't realize you're being squeezed unless your body language tells him.

"First she squeezed me out of my exit cards … and then she endplayed me."

An endplay is when a defender is put in a position of having to lead a card, but whatever card he leads will give the declarer a trick.

There are many different kinds of endplays. Here's one example. These are everybody's last two cards.

If anyone else leads a club, East will be able to win a club trick (try it). But if East is on-lead, he is endplayed. If he leads the  J, dummy's

J, dummy's  Q will win the trick, and then the declarer will win the last trick with the

Q will win the trick, and then the declarer will win the last trick with the  A. If instead East leads the

A. If instead East leads the  K, it will lose to the

K, it will lose to the  A, and then the

A, and then the  Q will win the final trick.

Q will win the final trick.

So Toni (or Annabel) first squeezed him out of his exit cards, meaning he had to discard all the cards he could have led safely, and then she allowed him to win a trick, endplaying him in some manner.

Pages 177-78, the IMP chart:

Did you notice that as you win by larger and larger amounts, you get fewer and fewer additional IMPs? The chart is designed this way so that one peculiar hand won't decide an entire match. Rather, the winner is the team that consistently does better.

Page 204:

I knew what it meant to … pull trump.

To pull trump means to lead the trump suit and keep leading it until the opponents don't have any trump cards left.

Pages 218-19, Deborah in the closet:

We bridge players are unusual, to say the least. When the average male reads Deborah's story, he no doubt wishes he could have been there when she stepped out of the closet. When I read it, I wished I could have been there too, but I wanted to see that bridge diagram! If it had Trapp stumped, it must have been a very interesting hand.

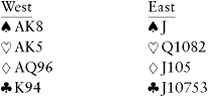

Page 229, the post-mortem hand:

How did Trapp know he could make four spades on this hand?

He didn't. He was dealt nine spades. Do you know what bridge players call a nine-card suit?

Trump!

Page 231:

I won't go through the rest of the hand. Maybe you can figure out how to take ten tricks. I did, apparently.

I've made an approximate reconstruction of the hand based on what West said afterward. Look at West's hand. It's no wonder he doubled.

Alton could only let the opponents win three tricks. When analyzing a hand, it helps to look at each suit separately.

By leading the  Q, Alton was able to lose only two spade tricks. He could afford just one other loser.

Q, Alton was able to lose only two spade tricks. He could afford just one other loser.

Since he had no hearts, he had no heart losers. He could play a trump any time an opponent led a heart.

Even though he only had one club, he should have taken the club finesse. When it worked, he could then have discarded a diamond on the second club winner.

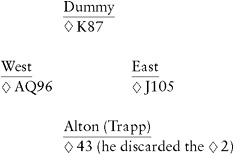

That would have left this diamond situation:

Alton now would have led the  3. West could have played his ace and won the trick, but that would have been Alton's last diamond loser.

3. West could have played his ace and won the trick, but that would have been Alton's last diamond loser.

In the end, he lost two spades and one diamond. Or, counting winners instead of losers, he won seven spade tricks, two club tricks, and one diamond trick.

Page 251:

"… MUD from three small."

"… upside-down count and attitude."

"She was squeezed in the black suits."

MUD refers to a defender's choice of opening leads. There are standard opening leads from certain card-holdings. For example, if you have three cards in a suit, headed by an honor card, you would normally lead your lowest card. So from  K72, it is normal to lead the

K72, it is normal to lead the  2. If you have two small cards in a suit, you would lead the higher. So from

2. If you have two small cards in a suit, you would lead the higher. So from  85, you would lead the

85, you would lead the  8. Where people tend to disagree is on what to lead from three small cards, say

8. Where people tend to disagree is on what to lead from three small cards, say  852. MUD is one possibility. It's an acronym for Middle-Up-Down. If you agree to lead MUD, you would lead the middle card, the

852. MUD is one possibility. It's an acronym for Middle-Up-Down. If you agree to lead MUD, you would lead the middle card, the  5. Then the next time the suit was played you'd play "up," with the

5. Then the next time the suit was played you'd play "up," with the  8, and the third time "down," with the

8, and the third time "down," with the  2.

2.

Personally, I don't like MUD, since the suit has to be played three times before I can figure out what's going on, which makes my partner's opening lead about as clear to me as the name implies.

Upside-down count and attitude is the reverse of standard signals.

In standard signals, a high card encourages and a low card discourages. If you play "upside down," then a low card encourages. That refers to attitude.

Count signals tell your partner how many cards you have in a suit. Playing standard signals, a low card says you have an odd number of cards. A high card shows an even number of cards. Your partner is expected to count the number of cards he has in that suit, and the number of cards the dummy has in that suit, and then figure out how many cards the declarer has in the suit.

If you play "upside down," then a low card shows an even number, and a high card shows odd.

Believe it or not, there are theoretical reasons why you would want to do this, and people have written entire books discussing the merits of different signaling methods.

"She was squeezed in the black suits" does not refer to a woman trying to fit into a bikini that's too small for her. A squeeze occurs when a defender has to make a discard, but whatever card she chooses will give the declarer a trick. When you're in such a situation, having to make discard after discard, it feels like you're in an ever-tightening vise.

You can never be squeezed in just one suit. For a squeeze to work, one defender has to be put in the position of trying to protect two suits. The black suits are spades and clubs, of course.

Page 261, 25 percent slam:

Taking a finesse is like flipping a coin. It will work 50 percent of the time. The odds of a coin flip coming up heads are 50 percent. The odds of flipping a coin twice and getting heads both times are 25 percent.

Toni was right to feel fixed. The odds of two finesses succeeding are 25 percent.

Before you feel too bad for them, however, Toni and Alton were most likely lucky on other hands. In every session of bridge, you will get some lucky boards and some unlucky ones. Bridge players tend to dwell on their unfortunate results, especially when they occurred during the final round, after all the other results were already water under the bridge (pun intended).

Pages 267-268, computer hands:

The boards had been predealt. There were tiny bar codes on each card. A special card-dealing machine had dealt according to specific hand records.

You often hear bridge players complain about "computer hands," as if a computer designed them to be especially diabolical. That is a myth. Computer hands are just as random as human-dealt hands. The reason they are used is simply to make sure that the same hands are played in every section; and there's the added benefit of the players getting to see the hand records after the session is over.

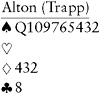

Page 273, the donkey hand:

I told her about the donkey hand. She didn't think it was my fault. She said there were lots of times when it's right to overtake your partner's king with your ace. "You might need to unblock… ."

The diagram on the opposite page gives an example of when it would be right to overtake your partner's king with your ace in order to unblock the suit.

The contract is 3NT, and West makes the normal opening lead of the  K. If you look at the other suits, you will see that the declarer can take plenty of tricks: three heart tricks, five diamond tricks, and three club tricks. So it is imperative that East-West take five spade tricks before the declarer wins a trick.

K. If you look at the other suits, you will see that the declarer can take plenty of tricks: three heart tricks, five diamond tricks, and three club tricks. So it is imperative that East-West take five spade tricks before the declarer wins a trick.

If East plays the  4, the suit will be blocked. East will win the second spade trick with the ace, but will have no more spades left and will have to lead another suit, allowing the declarer to make the contract. So the correct play is for East to overtake his partner's

4, the suit will be blocked. East will win the second spade trick with the ace, but will have no more spades left and will have to lead another suit, allowing the declarer to make the contract. So the correct play is for East to overtake his partner's  K with the

K with the  A and then lead the

A and then lead the  4. This will unblock the suit and allow East-West to take five tricks and set the contract.

4. This will unblock the suit and allow East-West to take five tricks and set the contract.

Page 305, Alton's Rule:

If you can see that plan A won't work, don't do it, even if you don't have a plan B.

Alton's rule is a good one. If you're stuck, it often helps to let the opponents win a trick. Remember, they don't know what your problem is. They can't see your hand. Quite often, they'll lead a card that helps you out.

Page 307:

I started with six diamonds in my hand, and the dummy began with two, for a total of eight. That meant the opponents had five diamonds between them. If they split 3-2, I could run off six diamond tricks.

If you are missing five cards in a suit, the odds of them splitting 3-2 are 68 percent. So really, it would have been unlucky if the diamonds hadn't split 3-2. Even if that had happened, however, I still think Alton would have gotten a "nicely played" from Trapp. An unlucky lie of the cards wouldn't change the fact that his line of play was both accurate and elegant.