As 1939 drew to an end Admiral Doenitz’s hands were still tied by Hitler. Not in the matter of restrictions: the war was swiftly moving toward unrestricted submarine warfare. Doenitz’s problem was that he still did not have enough U-boats; they were not coming out of the yards quickly enough to do what he wanted.

Hitler was preoccupied with the land war, and when he thought of the navy, it was Admiral Raeder’s navy, the fleet of battleships, pocket battleships, and heavy cruisers for which that admiral had such high hopes.

Hitler had achieved his aim of conquering Poland, now split between Germany and the USSR. The war in the west had settled down to something reminiscent of 1914, a war of entrenchment along the eastern frontier of France. The French expected a German attempt to invade. That month mines took thirty-three merchant ships, totaling 82,000 tons, while the submarines took twenty-five ships, totaling 81,000 tons.

* * *

As long as matters grew no worse at sea, there was no emergency. But the Chamberlain government had to look to the future, and food loomed large as a vital problem. In late November a special subcommittee of the war cabinet was formed to consider the future problems of food management. The chairman was Sir Samuel Hoare, the Lord Privy Seal; other members included the minister of agriculture and fisheries, the minister of food, the minister of health, the minister of shipping, and the secretary of state for colonies, all of them vitally concerned with the problems of producing, delivering, and allocating food, and of making certain that the island kingdom was fed.

Supplies were getting so tight that plans were made for rationing. W. S. Morrison, the minister of food, said his two anxieties were sugar and cereals, particularly the latter. By the end of 1939 England would have only an eight-week supply. That would mean the closure of some flour mills.

As for sugar, the time for rationing was coming, as with bacon and butter. The hope for the future lay in Cuba, and that meant ships.

The minister of shipping, Sir John Gilmour, was feeling put upon. He was hearing the same thing from the army, navy, and RAF, as well as from the ministry of supply. Only this day he had received an anguished call from the French government to help them out. The French had arranged for a naval escort to accompany a convoy bringing aircraft from New York. But they had not arranged for enough shipping tonnage to carry the planes. They had therefore called on the British. Sir John had been forced to divert a British ship, which was about to sail for Australia, and which now would have to go to Le Havre, then back to New York, and then to Australia to bring back grain and meat.

But what of the future?

The minister of health, Walter E. Elliot, said that the government had already cut food imports from 59 million tons per annum to 47 million tons, and could, if necessary, cut to 19,800 million tons. But of course that depended on the ability of British farmers to produce. The minister of agriculture, Reginald Dorman-Smith, said that was a matter of money. If the government would spend enough money, the farmers would bring in the bacon. So the questions of rationing (which items) and production (which crops) and shipping (how much) were referred back to the war cabinet. Everyone knew that this was just the beginning. At the next meeting early in December, a far more explosive issue was raised. What was to be done about distilling?

Some members of the committee felt it was hard to justify continuation of liquor distilling in the face of the coming shortage of grain.

Complete stoppage of distilling for a year would not affect the export trade materially, said one of the experts from the ministry of agriculture.

But what about the home front?

There was enough stock to last three years.

And then what?

Who could say?

Who, indeed. The delicate matter was tabled.

And what about brewing?

That was not even discussed. The thought of cutting out beer was too dismal to consider.

* * *

The last month of the year saw a general slackening of U-boat efforts as well as anti–U-boat efforts. The distribution of antisubmarine forces indicated that 100 destroyers were available in British home waters, plus 14 patrol vessels, 10 escorts, 5 motorized antisubmarine boats, 36 armed trawlers, and 15 yachts. But in fact, as Admiral Forbes reported, at any given moment perhaps only 45 percent of these vessels were fit for service; the others were laid up for repairs. But the good news was that another 100 trawlers were about to be delivered for antisubmarine work. That would mean more escorts for convoys; and by December it was apparent that escort was the key to everything. During the month only 3 ships in escorted convoys had been sunk.

This was the month in which the British submarines won their first victory over their opposite numbers. On December 4, H.M.S. Salmon encountered another submarine eighty-five miles southwest of Lindesnes and sank her. This was Lieutenant Wilhelm Froehlich’s U-36, out on her second war patrol. On the first patrol, in September, Froehlich had sunk two ships. But this time he had been careless, caught on the surface by the enemy. He and a crew of twenty-nine men went to the bottom.

British submarines were not basically part of the antisubmarine force, although their record during the war was an admirable one. But other, more traditional antisubmarine measures were also being taken. A new school of antisubmarine tactics was set up to train asdic operators. The larger merchant ships, which could stand the recoil of a deck gun, were rapidly being armed. About 23 percent of those that would be armed received their guns by the end of October. And the RAF Coastal Command was increasing its searches, escorts and patrols.

In October the British began paying special attention to the North Sea. Norway was a principal supplier of iron ore for the furnaces of Britain—and for Germany. From the beginning of the war, the Admiralty went out to stop the German ore import and, by submarine attack and mine fields, had done such an effective job that by the end of 1939 Winston Churchill was concerned lest the Germans invade Norway and secure her raw materials. He was talking of invading Narvik and Bergen to keep those two ports open for the British trade. So far he had been unable to convince the rest of the war cabinet. Across the North Sea the Germans were also talking of invading Norway, using the same line of reasoning.

After sinkings of some Norwegian ore ships early in the war, the Royal Navy thereafter set up ore ship convoys, with a battleship-covering force in case the German battle fleet chose to try to stop the shipments. After two successful convoys the Germans retaliated by sending the battle cruiser Scharnhorst into these waters. She sank the British armed merchant cruiser Rawalpindi on November 23. Then came a good deal of activity by major naval units, which emphasized to both sides the importance of control of the Norwegian North Sea ports. On the way home from chasing the Germans, Admiral Forbes’ flagship, the battleship Nelson, ran into a mine laid by a submarine in Loch Ewe, and was laid up for weeks. It was another small triumph for Admiral Doenitz. The magnetic mines laid by the 250-ton coastal U-boats were doing their work far more effectively than the attack submarines. England was lucky in that the Germans had virtually exhausted their supply of magnetic mines by the end of the year, and had to slow the minelaying. But the five magnetic mine fields laid off the east coast and the Thames estuary, and the mines laid around the entrances to British naval bases, continued to take their toll.

By the beginning of 1940 the London Submarine Agreement was in tatters. The prohibition of attacks on passenger liners had been removed. Neutral ships were not safe east of twenty degrees west longitude, which bisects Iceland down the middle. In November the United States government had declared a war zone that extended from the twenty degrees east longitude, covering all of the British Isles and France. That meant American shipping was forbidden in these waters. It was not a particularly important matter to Britain just then, since American shipping was limited. It was a sign, however, of Germany’s steady move toward unrestricted submarine warfare; and American acceptance of the German extension of the sea battle zone was a sign of the low state of relations between the United States and Britain, a matter of serious concern to Churchill, and for which Ambassador Joseph Kennedy was largely responsible.

* * *

The Germans entered 1940 with a vigorous mine-laying campaign around Britain. Some small U-boats were used in this work, but most of it was done by surface vessels. From the beginning of January the Germans concentrated on neutral shipping. Doenitz does not mention this in his autobiography, but the evidence is overwhelming. Of the fifty-four ships sunk by submarines in January, forty-three were neutrals. The idea was obviously to put pressure on neutral shipping to stay away from Britain. At first the pressure was exerted in the North Sea. The attack on the most logical area, the Western Approaches to the British Isles, did not begin again until the middle of January, when half a dozen of Doenitz’s Type VII submarines appeared.

As the year opened Churchill continued to be optimistic. At the war cabinet meeting on January 2 he crowed that the previous week had been the best since the beginning of the war insofar as shipping losses were concerned. He was not looking at the neutral ship records.

Two weeks later Churchill had to report to the cabinet that U-boat activity had increased seriously. Also, he had to take note of German broadcasts denying a British claim to have sunk seventy submarines since the war began. The Germans said the figure was closer to thirty-five. The actual figure was eleven; the German announcement duped Churchill into believing that the figure was around forty. But Churchill was sure of the figures for delivery of German U-boats to Doenitz, and in this he was much closer to the facts: he claimed that up to Christmas only eight new boats had been added to the fleet. It was more, but not many more. However, by now there were enough boats that Admiral Doenitz felt confident in renewing the open sea campaign in the west. The U-boats went out, not to attack convoys in packs but to attack individual ships. During January only nine ships out of fifty-four were sunk in convoys; three of these were the work of Lieutenant Lemp, who may have been doing penance for the Athenia. Lemp’s return to grace was complete on this patrol; he was the captain who put the torpedoes into the battleship H.M.S. Barham and knocked her out of action for many weeks.

More tragic for the British was the loss of H.M.S. Exmouth, a senior destroyer and flotilla command ship in the Moray Firth near Tarbatness on January 21. The Exmouth was escorting the merchant ship Cyprian Prince, which was carrying valuable materials for the rebuilding of the Scapa Flow defenses. When it was learned that the Danish ship Tekla had been torpedoed fifty minutes northeast of Tarbatness at 5 A.M., the Exmouth was warned to watch out for that submarine.

There was no need for that; Lieutenant Commander Werner Heidel’s U-55 had already pulled out into the North Sea where, that same day, she sank the Swedish freighter Andalusia. But the danger was real nonetheless. Lieutenant Commander Hans Jenisch’s U-22 had moved into that same North Sea area. The Cyprian Prince was traveling along at a safe distance behind the Exmouth; she had been warned that the destroyer was submarine hunting. Night came. The little convoy proceeded north. At about 4:45 A.M. the Exmouth was still in sight, but dimly, when the chief officer of the merchant ship heard several explosions in the vicinity of the destroyer. They sounded like depth charges. But four minutes later came another explosion, and the destroyer passed out of sight. The Cyprian Prince’s captain altered course and passed through the sea where the Exmouth had been. Nothing remained but bits of flotsam. The captain of the Cyprian Prince heard voices in the water, and saw some lights flashing. He had stopped his engines and prepared to make rescue attempts. But then he realized that he had a vulnerable cargo aboard and so he started his engines and went on, maintaining radio silence. Only when the merchant ship arrived alone at Kirkwall, just before 6 P.M., did the Admiralty learn of the disaster. Other ships rushed to the area, and they found one life buoy from the Exmouth, floating in the water among a handful of orange crates. That was all.

The sinking of the Exmouth aroused a debate within the war cabinet. Had the captain of the Cyprian Prince done the right thing in abandoning the survivors of the warship when he might have rescued them?

Unfortunately, said the first lord of the Admiralty, the captain had done just the right thing, given his situation with virtually irreplaceable military stores aboard. It was a cruel war.

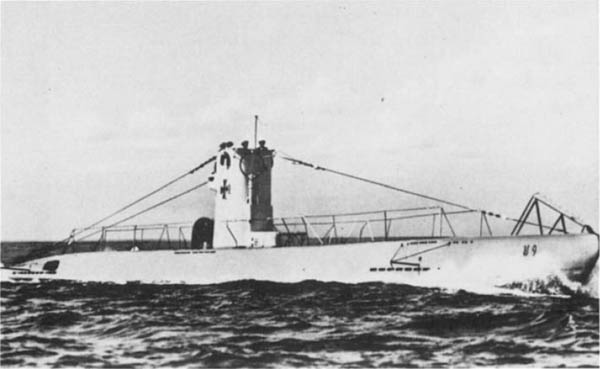

The U-9, a type IIB submarine, saw action early in the war.

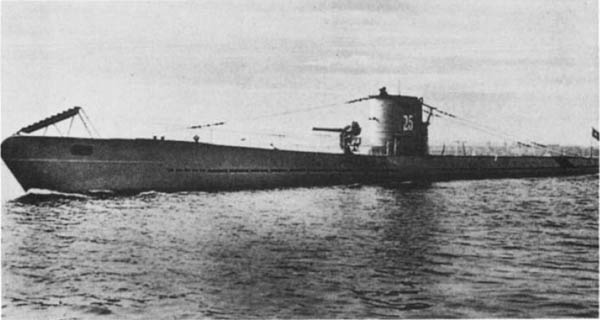

Another early sub, U-25, type 1A, at the outbreak of war

All photos © Imperial War Museum, London

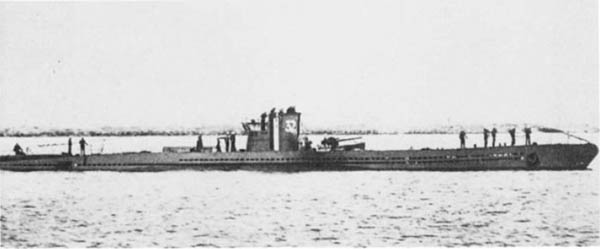

The sleek silhouette of U-32

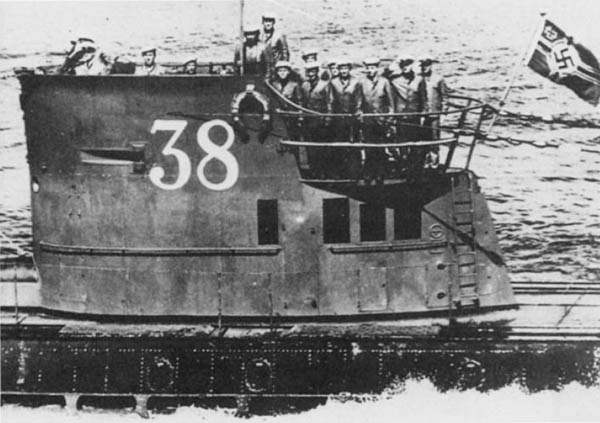

Achtung! Officers and crew of U-38 at a ceremonial shapeup

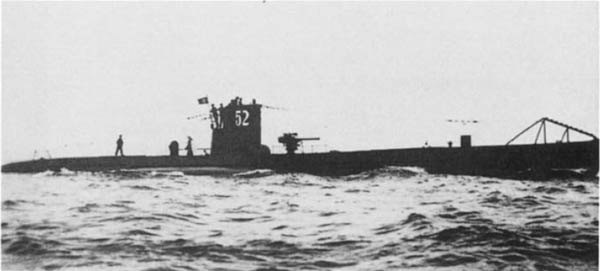

The U-52, a type of VII B sub, with its deadly cannon

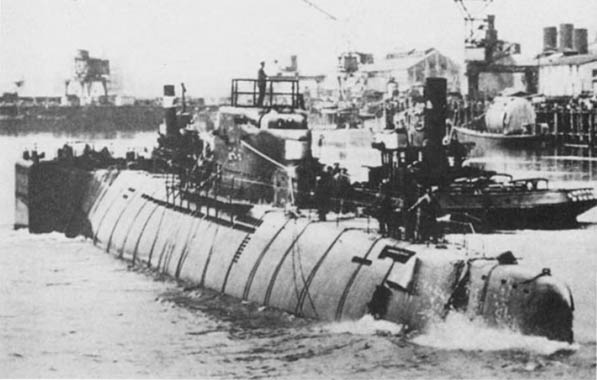

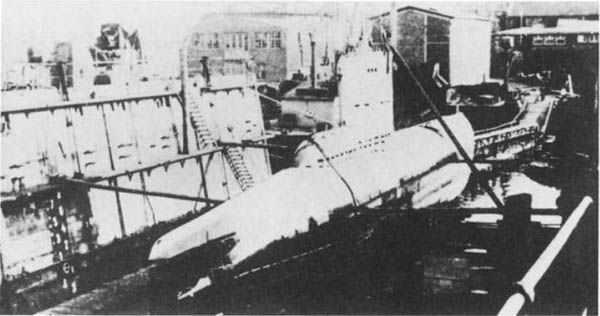

The launching of a later U-boat, type XXI

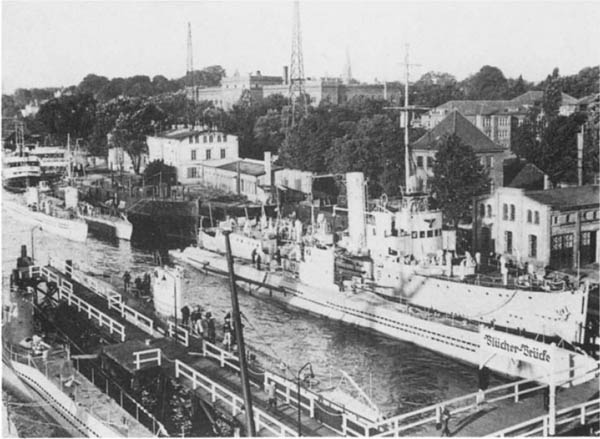

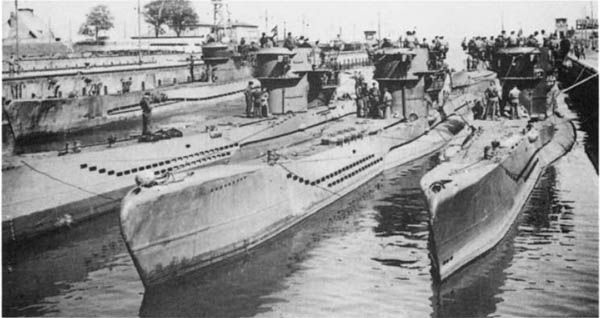

Submarines tied up at Kiel, the busy German wartime base

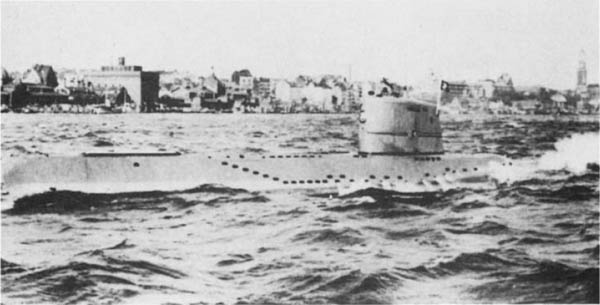

U-boat of type XVII

Subs at the impregnable pens in the Bay of Biscay

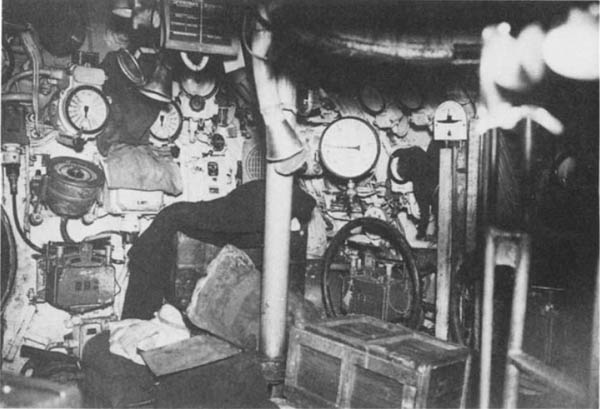

Closeup of U-boat trimming panel and hydroplane control

View of the control room of captured U-532

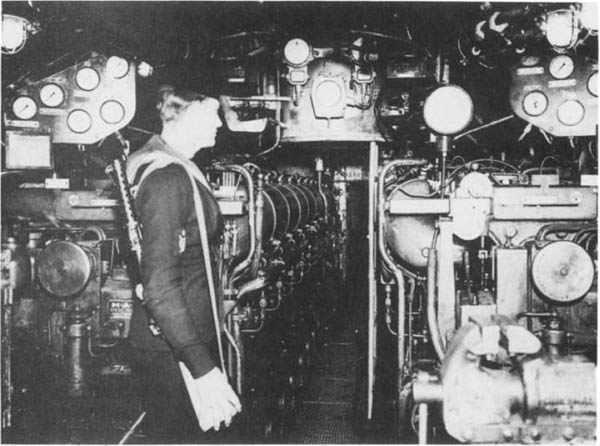

The cramped engine room of U-532

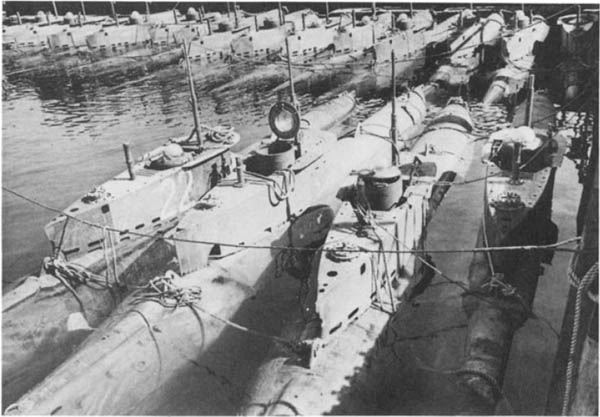

Two-man U-boats called Seehungs lying at anchor

A streamlined, electric underwater boat, type XXIII

U-boats preparing to surrender at Wilhelmshaven

U-boat, with the Union Jack aloft, after surrendering to RAF aircraft