THE PLACE: Ten Downing Street

THE TIME: 5 P.M. March 19, 1941

THE OCCASION: First meeting of the War Cabinet Battle of the Atlantic

Committee

The prime minister, Winston Churchill, took the chair. It was indicative of the vital nature of the business before this new committee that the Labour party’s number-two man, Ernest Bevin, was also in attendance. Others were: First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander; Lord Beaverbrook, the minister of aircraft production; and six other ministers, plus Admiral Pound, the chief of the Coastal Command, Air Vice Marshal A. T. Harris, and half a dozen other high-placed senior officers.

Churchill’s timing was perfect. Britain now had some of the sinews of war that she needed to fight the U-boats successfully. As much as technical equipment now, the question of defeat or victory in the eastern Atlantic would depend on the efforts these high officials and their subordinates would make.

They went over the shipping figures for the previous week and the weeks before. They could draw some confidence from the sinking of four U-boats in two weeks (U-551 was not yet sunk) and the performance of the escort service.

The prime minister again emphasized the absolute necessity of controlling the U-boats and his confidence that this would be done. Absolute priority, he reiterated, was to be given to controlling the U-boats in the Northwestern Approaches to Britain.

The British now had seagoing radar. It was far from perfect, there was trouble with echoes and false images, but they had a way of finding surfaced submarines that were beyond the reach of the asdic.

Also they had new techniques making use of old methods. The illumination of the convoy by star shells was extremely effective in bringing up the escorts to attack a surfaced submarine. And, some merchant vessels now also attacked with their deck guns. Star shells were soon augmented by “snowflakes,” an even brighter and longer lasting system of lighting the sky at night. All the old strictures against using radio were thrown off at the moment of attack. Each convoy member was instructed to report any U-boat movement, attack or threat that he saw—Immediately. Thus, the escorts were beginning to know what was going on inside their convoys.

Radio was playing a much greater role, as the shipping merchants had predicted at the outset. Lifeboats had recently begun to be equipped with small radio transmitters to assist rescues at sea. The development of radio telephone—talk between ships—made it possible for the escort commander to control his vessels swiftly and move them about. The improvement of depth charge equipment and techniques made it possible in the past few weeks to begin throwing a pattern of ten charges, rather than the former five.

And, finally, antisubmarine warfare had a new priority and a new headquarters at Liverpool, where Admiral Sir Percy Noble was the new commander of Western Approaches. In his headquarters he had an elaborate situation chart which at any time showed the movement of convoys and individual vessels plus the protective and air forces available.

Radio Direction Finding (RDF) was still in its infancy in Britain. The first truly acceptable set would not be ready until July, 1941. Also, a whole new training program for antisubmarine war was in development, which would include a month of intensive work for every new escort vessel before she went into action. The trouble until now had been that so desperate was the need for them that ships had been pushed out to sea almost as they came out of the yards, and the crews had been forced to learn from experience. Britain’s push in the shipyards, America’s fifty destroyers and new aircraft, and Canada’s corvettes had all bought Britain the time she needed.

But the trouble was still shortages, particularly of aircraft and escort vessels to cover the entire transatlantic voyage of the convoys and to bring more ships into convoy. As was agreed, the convoy was indeed the solution to the U-boat. In January, for example, 2,966 ships had been convoyed in all directions, and only 13 had been lost. To be sure, the losses in February and March were much higher, but January showed what could be done.

The percentage of lone ships sunk by U-boats was about four times as high as that of convoy ships sunk, but as yet there were not enough protectors to do the job.

* * *

Admiral Doenitz was looking happily to the future. The U-boat building program was now in full swing and he expected to have 250 U-boats by the end of the year. A full-scale enlistment program was operating in Germany, utilizing the stories of the heroic captains to the hilt. “War correspondents” were now going along on U-boat cruises, to get all the glorious details and write them up for broadcast, newspaper and magazine stories. At the moment Doenitz had only about 30 submarines operational, and of those it was hard for him to keep more than a dozen at sea at one time, but they were doing a great deal of damage. In March 206,000 tons were lost to U-boats. Churchill could take the optimistic view: that the loss was considerably lower than in September and October, 1940, the last period of intensive U-boat activity, and that the highly vaunted “spring offensive” had not really materialized. Still, 200,000 tons in a month meant 1,200,000 tons in a year, or five percent of Britain’s registered tonnage at the outbreak of war.

Doenitz’s answer to the increasing vigilance of the British in their Northwestern Approaches was to carry the war farther west and south.

On April 2, Lieutenant Engelbert Endrass in U-46 found Convoy SC 26, homebound to England from North America, far to the west of any point at which a convoy had been attacked before: 58° north, 28° west. The Admiralty months earlier had asked for establishment of an air base in Iceland and cover for convoys, but it had not yet been done. The convoys had no destroyer escort as they traveled eastward below Greenland to Iceland, and this is where Lieutenant Endrass found SC 26. The only protection was the armed merchant cruiser Worcestershire, traveling between the fifth and sixth columns of the twenty-two-ship convoy.

Endrass began shadowing the convoy, making his reports to Admiral Doenitz. The admiral called up all nine boats that were operating north of 57° and west of 18°. They included Lieutenant Helmut Rosenbaum’s U-73, Lieutenant Commander Eitel Friedrich Kentrat’s U-74, Lieutenant Jost Metzler’s U-69, Lieutenant Commander Robert Gysae’s U-98, and Lieutenant Herbert Kuppisch’s U-94.

The Admiralty was keeping track of Doenitz’s transmissions back and forth to his U-boats, and at 8:55 P.M. sent a message to the Worcestershire, indicating that SC 26 was probably being shadowed by a U-boat. When the message was received, the Worcestershire’s captain consulted with the captain of the Magician, who was commodore of the convoy. They agreed that under the circumstances, without escorts, they had already set up the best possible defense using evasive tactics. The first move was taken at 10:30 P.M., and the convoy turned to course 104 degrees at six knots.

* * *

Endrass tracked the ships on the night of April 2. The course change at 10:30 was a signal that the enemy ships knew something was in the air. At midnight he attacked. His first victim was the tanker British Reliance, the ship just astern of the commodore’s vessel. She was hit by a torpedo on the port side, forward. Thirty second later she was hit by a second torpedo, amidships.

The commodore saw all this, and although the stricken ship did not fire a rocket as ordered, he still made a course change, with an emergency turn of forty degrees to port. This turn faced the convoy directly at the submarine and caused Endrass to miss his next shots at another freighter. He moved around the convoy for nearly an hour. At 1:10 A.M. the convoy resumed its base course. Endrass then fired again, at the steamer Alderpool. The torpedo struck her in the port side. The commodore ordered another emergency turn, this time to starboard.

When the Alderpool was torpedoed, the captain of the Thirlby decided to stop and pick up survivors. He was engaged in this when Endrass’ U-boat was sighted on the port bow. The captain turned to put his stern to the U-boat and bring the four-inch deck gun to bear. This maneuver put the Alderpool between the Thirlby and the submarine, and the U-boat fired a torpedo, which hit the Alderpool. Then the U-boat fired two more torpedoes at the Thirlby; one missed ahead and the other astern. The Thirlby then went off at twelve knots, out of the convoy, on her own.

The steamer Athenic made the mistake of turning to port instead of starboard, and got out of line. Ten minutes later her captain broke radio silence: “U-boat in sight, bearing ten degrees.”

The commodore made another emergency turn to starboard.

Not all the ships followed. One that did not was the Athenic. She was completely out of line and out of the convoy. Her captain watched the U-boat and turned to try to ram. But Endrass was more interested in keeping track of the convoy than in any particular ship, so he moved off to the east to get ahead and wait for the convoy again on the base course.

From various directions other submarines were also trying to close the convoy.

And from the east where they had been escorting outward bound Convoy OB 304, the escorts Havelock, Hesperus and Hurricane were ordered to go to the assistance of the British Reliance. They put on speed to twenty-four knots and headed west.

The convoy went on, leaving its stragglers. In the next two hours, two more turns brought the convoy back to its base course. There was some confusion but by 4 A.M. the convoy was in good order.

At 4:06 A.M. the convoy was hit again; this time the second ship in the sixth column, the Leonidas Z. Cambadas, was torpedoed by Kentrat’s U-74. Immediately afterward the men on the bridge of the commodore’s ship saw a torpedo track crossing from the Magician’s starboard bow to her port quarter. A few seconds later the leader of the fourth column, the West-pool, was hit by two torpedoes on the starboard side and sank immediately. She was the victim of Rosenbaum’s U-73, which had just joined up.

The commodore decided to turn to starboard and fired off green flares. But he saw that so many ships were already turning to port that he decided to conform, lest he split up the convoy further. In all the confusion, the Tennessee turned back to the west to go it alone and avoid the U-boats. While moving westward, her radio operator picked up a distress signal from one of the lifeboats of the British Reliance. She went on twenty miles and found the boat and rescued the survivors. It was the first case of the new lifeboat radios being directly responsible for rescue. The Tennessee then set a course for Iceland and arrived without incident.

At 4:15 A.M. Kentrat torpedoed the steamer Indier.

The commodore looked over his convoy. The moon had set at 3:30 A.M., but the northern lights kept the sky bright and the ships stood out against the clear, quiet sea.

“Do you think it’s any use scattering?” he radioed the Worcestershire.

“Yes, I think it is,” was the reply from the merchant cruiser.

So the commodore gave the order to scatter and meet again at the rendezvous point, where they were to pick up the escort ships that would take them into the Northwestern Approaches. The convoy dispersed at 4:20 A.M.

On receiving the commodore’s order to disperse, the steamer Ethel Radcliffe turned to port and held that course for fifteen minutes. Then she swung back to her original course, and as she did so, a U-boat appeared on the surface to port. The captain swung the ship around, “hard aport” and tried to ram. The U-boat evaded. The gun crew fired one round from the deck gun and the submarine dived. The Ethel Radcliffe then headed home to England, arriving without incident.

* * *

The steamer Tenax left the convoy on the orders and steamed due north for an hour and a half. She turned east then and was heading toward England when a U-boat appeared on the surface off her port bow. The captain swung the ship and the crew got off one round from the deck gun before the submarine submerged. Tenax then headed for the rendezvous for stragglers and at 4:20 A.M. on April 4 she sighted the H.M.S. Hesperus. The escort took her safely to the British shore.

* * *

The tanker British Viscount chose to stay on the base course to England. At 4:35 A.M. Rosenbaum torpedoed her on the starboard side and she burst into flames, a beacon lighting the sea for miles around.

* * *

The steamer Welcombe altered course to port to put the burning tanker astern. At 4:45 A.M. the captain sighted a U-boat only 200 yards away on the port quarter and the deck gun crew began firing. They claimed a hit, the submarine heeled violently and disappeared. At daylight the ship altered course to seventy degrees and began to zigzag toward England.

* * *

The steamer Helle sighted a U-boat just after the convoy scattered, but the submarine did not attack. At dawn she began zigzagging towards the rendezvous point at eight knots.

* * *

The Worcestershire increased her speed to fourteen knots, to proceed ahead of the convoy for two more hours. Then the local escorts were expected to show up and the Worcestershire could turn about and head back to Halifax.

But Kentrat’s U-74 had moved out ahead to wait for the convoy, and at 4:43 A.M. she was in position to attack the Worcestershire. The captain of the merchant cruiser saw the torpedo coming, and ordered the rudder to port, on the starboard side of the forecastle, and jammed the rudder hard aport. All she could do was steam in circles. So the captain stopped her and she lay there dead in the water, lit up by the blazing British Vicount. After an hour, the crew managed to get the rudder working and centered. It would move fifteen degrees port and starboard. A course was set to the north, to get out of the submarine operating zone. Messages were sent out about the status of the convoy.

* * *

At 9:45 A.M. on April 3 the Hurricane was detached from the other escort vessels to escort the Worcestershire and took up position. The Worcestershire was making seven knots, and Hurricane circled her endlessly, at fifteen knots, all the way to Liverpool.

* * *

Somewhere north of the convoy the Thirlby was moving along at twelve knots, heading for England. From time to time the bridge watch caught sight of a submarine on the surface. At 5:20 A.M. on April 3 a torpedo struck the Thirlby a glancing blow on the starboard side. It made a screaming noise, and skidded along the side of the ship, and then bounced off without detonating.

The U-boat appeared again just before 6 A.M. and the gun crew fired a round. The U-boat dived.

* * *

After giving the order to scatter, the commodore of the convoy set a course to the east and sped along zigzagging, toward a new rendezvous for stragglers. At dawn on April 3 ships began to come in sight and the commodore ordered them to take station on him.

* * *

The Havelock and Hesperus continued to steam westward at top speed, until noon on April 3, when they sighted the commodore’s ship and five others. They set up a rendezvous with the escorts Veteran and Wolverine for 4 P.M. and sped on.

* * *

The Veteran and the Wolverine parted company from Convoy OB 304 at 6:45 A.M., but they were not quite sure where they were supposed to find SC 26. At noon they had a message from the Worcestershire giving them the most probable location.

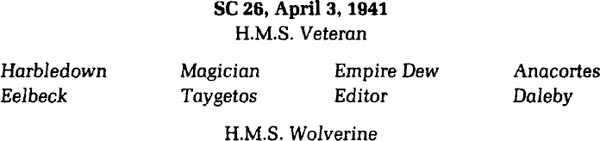

At 4 P.M. they found the convoy. It now consisted of eight ships. They were formed into four columns and the convoy went on under escort (see table below). At 10 P.M. the convoy made a fifty-degree alteration of course to starboard.

* * *

All day long Lieutenant Gysae’s U-98 had been speeding to catch up with the convoy. At 11:30 P.M. she found the straggler Helle and torpedoed her. The Helle began sending: SSS SSS SSS SSS . . .

Gysae did not stop but hurried on, and just before 3 A.M. on April 4 came up with the Welcome, which had quit zigzagging at dark. Gysae torpedoed the ship. She began sending SSS SSS SSS SSS . . . and was still sending messages almost until the moment when she went down fifteen minutes later. While the boats were assembling, the U-boat turned a searchlight on them, then switched to the stern of the Welcombe, apparently checking the name.

* * *

At 2:42 A.M. on April 4, Lieutenant Kuppisch’s U-94 attacked the Harbledown, hitting her with two torpedoes on the port side. The entire bridge collapsed, which meant the wireless office too, so no signal was sent. But the commodore’s ship Magician was right alongside, and he saw. He ordered an emergency turn to starboard. The convoy turned and steamed at 143 degrees for twenty-seven minutes, then returned to the base course.

The Wolverine had been off the port beam of the convoy. She sped up the side but found nothing. She fired two new experimental rockets of a quarter-million candlepower each. They lit up the sky brilliantly for half a mile, but seemed to intensify the darkness beyond that point.

Wolverine continued the search until 4 A.M., when she rejoined the convoy.

On seeing the rockets fired by Wolverine, the Veteran came rushing back to the end of the convoy and saw the Harbledown stopped dead. The Veteran prowled around for a while and then rescued the survivors of the Harbledown. She rejoined the convoy at 6:15 A.M.

The two escorts patrolled restlessly all day long but there were no more attacks. During the afternoon of April 4 they were joined by the escorts Convolvulus, Verity, Vivien, and Chelsea.

* * *

The Athenic steamed on toward England at her own pace after sighting that periscope early on the morning of April 3. She made no attempt to rejoin the convoy but moved along without incident until just before 7 P.M. on April 4, when she was struck out of the blue by a torpedo on her starboard side. The SSS message was sent and the crew abandoned ship. Twenty minutes after they took to the boats a second torpedo struck near the engine room and fifteen minutes later the ship sank. Lieutenant Rosenbaum was given credit for sinking her.

* * *

At 7:25 P.M. on April 24 the Daleby broke radio silence to report a periscope between the columns. The escorts made what appeared to them to be doubtful contact, and dropped a few depth charges, to placate the captain. They still did not believe that U-boats got inside convoys.

But the presence of six escorts with seven merchant ships was enough to discourage any U-boat captain, and the convoy—what there was left of it—suffered no more casualties, moving into the north channel on April 8.

* * *

The reports of Doenitz’s captains following this convoy attack convinced him that the British had not invented anything new to harry his submarines, and that the loss of his top three U-boat captains in two weeks in March had been little more than coincidence. But there Doenitz erred, for although no spectacular devices (such as sonar) had yet come onto the scene, there had been plenty of change. Most of all, the change had been in the upgrading of attention now given the war against U-boats by the British government.