ONCE AGAIN, MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. WAS THINKING OF DEATH. IT WAS January 2, 1965, and King, driving from Atlanta to Selma with his close friend Ralph Abernathy, reflected on his past brushes with mortality and those that lay ahead. “You know, I had the feeling I was going to be killed in Mississippi,” Abernathy later recalled King saying. “I was certain of it. Fortunately, it didn’t happen. But I’m sure it will be in Selma. This is the time and place.”

King told Abernathy, SCLC’s vice president, that he wanted Abernathy to assume the presidency of the organization if he died. Abernathy, who was accustomed to King’s morbidity, shrugged off the request as impractical. Because they were almost inseparable, he too would likely lose his life along with King. But King insisted, and Abernathy, hoping to change the subject, agreed.1

It was snowing lightly when they arrived at their first stop in Selma, the home of Sullivan Jackson, the city’s only African American dentist, who always provided King with a place to stay, food to eat, and even clothes to wear during his trips to Selma. There, the two men met with old acquaintances and rested briefly until leaving for King’s sole event that day, a celebration of the 102nd anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation at Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church and the opening of King’s campaign for voting rights in Alabama.2

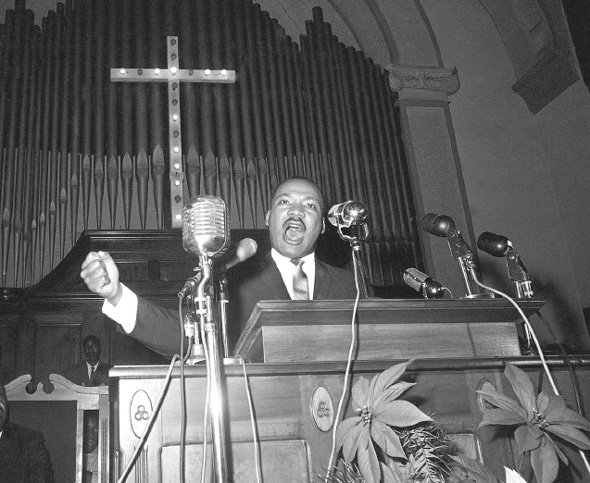

As King and Abernathy neared their destination, the headquarters of the voting rights movement in Selma, they saw police cars parked at both ends of Sylvan Street, flanking the church. They wondered if the police were there to arrest them for violating Judge James Hare’s blacklist that prohibited them from gathering together in a group. But nobody bothered them. As they entered the building, they could hear singing, clapping, and loud, boisterous music. The crowd, later estimated at seven hundred, had filled the chapel to see King. He was greeted with a burst of applause and received a standing ovation as he took the pulpit.

He had come to Selma, King told his audience, because American democracy was in peril: it did not exist for America’s “22 million black children,” many of them mature adults who, despite their rights as citizens, could not vote. His listeners were familiar with the obstacles Alabama placed in their way: the Board of Registrars, located in the Dallas County Courthouse, opened only twice a month, and its staff usually arrived late, took long lunches, left early, and almost always ignored black visitors. Their oral and written tests were so complicated that not even the most brilliant teachers at Tuskegee Institute could pass them. And if that failed to dissuade black applicants, intimidation and violence were used against those who showed up to apply.

King told his audience that he had come to join their fight against the injustices in their city. “Today marks the beginning of a determined, organized, mobilized campaign to get the right to vote everywhere in Alabama,” he said, and the people cheered with an intensity that shook the building. “If we are refused, we will appeal to Governor George Wallace. If he refuses to listen, we will appeal to the legislature. If they don’t listen, we will appeal to the conscience of the Congress in another dramatic march on Washington.” His voice rose as he challenged them to march and “be willing to go to jail by the thousands.” Drawing on the speech that he delivered at the Lincoln Memorial on May 17, 1957, he said, “Our cry to the state of Alabama is a simple one, ‘Give us the ballot!’”

“That’s right!” they yelled back, everyone now on their feet.

“When we get the right to vote we will send to the statehouse not men who will stand in the doorways of universities to keep Negroes out, but men who will uphold the cause of justice: Give us the ballot!”

They were all with him now as he repeated the phrase again and again, crying out, “Speak! Speak!”

“We are not on our knees begging for the ballot,” he concluded. “We are demanding the ballot! . . . We will bring a voting bill into being on the streets of Selma!”

Martin Luther King Jr. addressing a Selma audience on January 2, 1965. King’s repeated admonition “Give Us the Ballot!” marked the official beginning of the voting rights crusade. © HORACE CORTY/AP/AP/CORBIS

“It’s time,” the people agreed. “Yes! Yes!” Then everyone linked arms and sang, “We Shall Overcome,” providing the opportunity for three white observers, a state trooper and two deputy sheriffs, to slip out of the room unseen.3

King had shown that he was ready to join the voting rights struggle in Selma, just as Bernard Lafayette and James Forman had done before him. King’s day was not over, however—he still had work to do. Before leaving Selma he met with reporters and later held a long strategy session with Amelia Boynton and other colleagues. John Lewis, representing SNCC, was there. This pleased King, as he was hoping to avoid the internal antagonisms that threatened to tear the movement apart. King’s old aide, Jim Bevel, was present as well. He and Hosea Williams, a decorated World War II veteran and another member of King’s inner circle, would be responsible for finding people willing to participate in the first march on Freedom Day, another voter-registration event like the one Jim Forman had organized in Selma in the fall of 1963. The date for the demonstration was set for just over two weeks away, on January 18, when the Board of Registrars would reopen for business.

Having helped to lay the groundwork for Freedom Day, King and his colleagues departed Selma. They were now part of a motorcade. Following them were FBI agents and Alabama law enforcement officers. If one were white, their presence might have been reassuring. In King’s case, however, it was not.4

PUBLICIZING FREEDOM DAY WAS DIFFICULT. BECAUSE THE CITY HAD NO newspapers, radio stations, or television stations targeted at the black community, Jim Bevel and his staff took to the streets. Workers were assigned to each of the city’s five election wards, where, in pairs, they passed out leaflets and encouraged folks to attend meetings on January 7. Mustering voters in each ward would be essential to effecting political change in Selma—once, of course, enough of its black voters succeeded in registering. “If we can get out and work,” Bevel told them, “Jim Clark will be out picking cotton with my father.”5

As usual, they found that older citizens were unwilling to join them. One elderly woman confessed that she had never heard of voting, and when they described its benefits—electing men who would see that their streets were paved and the garbage collected—she said it was just too dangerous for her to become involved. Others took the leaflets quickly and said, “Yeah,” obviously hoping to get rid of the civil rights workers before the police arrived.6

But Bevel and Williams were eloquent and persuasive speakers, and on occasion they shocked their listeners into action. At a youth rally that attracted two hundred students, Williams said, “If you can’t vote, then you’re not free. And if you ain’t free, children, then you’re a slave.” And when Sheriff Jim Clark’s deputies showed up at a meeting at Brown Chapel, Bevel wasn’t intimidated; instead, he commanded them to leave immediately and even yelled at one who tried to take his picture, both acts riveting an audience unaccustomed to seeing Clark’s troops follow a black man’s orders. “Things are starting to move here,” a volunteer from California wrote his parents. Bevel, Williams, and the other SCLC and SNCC workers were becoming cautiously optimistic that Freedom Day would be a success.7

King’s troops were unaware, however, that the greatest danger to Freedom Day—and to the civil rights movement itself—came not from black apathy or from Sheriff Clark’s brutality but rather from the FBI’s war against King. On January 5, while going through the mail that had accumulated over the Christmas holidays, Coretta Scott King opened a box containing a spool of tape and a letter. Believing that the tape was a recording of one of Martin’s speeches, she played it. She heard men laughing and sounds that seemed unmistakably sexual. Shocked and confused, she turned to the letter, which read,

KING,

In view of your low grade . . . I will not dignify your name with either a Mr. or a Reverend or a Dr. And, your last name calls to mind only the type of King such as King Henry the VIII. . . .

King, look into your own heart. You know you are a complete fraud. And a great liability to all of us Negroes. . . . You are no clergyman and you know it. . . . You could not believe in God. . . . Clearly you don’t believe in any moral principles.

King, like all frauds your end is approaching. You could have been our greatest leader. You, even at an early age have turned out to be not a leader but a dissolute, abnormal moral imbecile. We will now have to depend on our older leaders like Wilkins a man of character and thank God we have others like him. But you are done. . . . Satan could not do more. What an incredible evilness. . . .

The American public, the church organizations, that have been helping—Protestant, Catholic and Jews will know you for what you are—an evil, abnormal beast. So will others who have backed you. . . .

King, there is only one thing left for you to do. You know what this is. . . . You better take it before your filthy, abnormal fraudulent self is bared to the nation.8

Mrs. King was aware of her husband’s philandering, but she seemed to accept it gracefully: “If I ever had any suspicions . . . I never would have mentioned them to Martin,” she later noted. “I just wouldn’t have burdened him with anything so trivial.” She was less concerned about the tape than the threatening letter. She immediately called her husband, who summoned his friends Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, Joseph Lowery, and his father, the Reverend Martin Luther King Sr. They listened to the tape and heard King teasing Abernathy along with “big, deep belly laughs”—so that part of the tape was authentic. As for the erotic noises, Young did not think it sounded like King. “Martin had a distinctive voice,” Young later wrote, “and it certainly wasn’t his.”9

King was stunned but knew immediately the source of this cruelty. The box was postmarked Miami, but of course it had originated in Washington, DC. He realized that the Bureau had him under close surveillance and possessed material that could destroy him. “They are out to get me, harass me, break my spirit,” he told friends in telephone conversations the FBI recorded, but he admitted that he was the author of his own misery. Whether he recognized the recording from his night at Washington’s Willard Hotel roughly a year before or he simply accepted that his infidelity had opened him up to this sort of attack, the reverend appeared resigned to his fate.

Confronting the FBI about the recordings did no good. Andrew Young and Ralph Abernathy agreed to meet with Hoover; however, the director passed them on to his assistant, Cartha “Deke” DeLoach, who flatly denied that the FBI had King under surveillance, claiming that his personal life was of no concern to the agency. The trip, Abernathy later wrote, was “a waste of time and money.”10

Those closest to King feared that he was on the brink of a nervous breakdown. He believed that the spool of tape was “a warning from God,” a sign that the Almighty Himself knew that King wasn’t “living up to his responsibilities.” He became an insomniac, and the Bureau did all it could to exacerbate his suffering. When King tried to steal a few hours of sleep at a safe house, the FBI learned its location and called the local fire department, which sent engines, their sirens screaming, to disturb his rest.11

The FBI’s latest outrage probably made King more determined than ever to launch the Selma campaign. He returned briefly to the city on Thursday, January 14, to announce new plans for Freedom Day. The events scheduled for that Monday, January 18, would now include not only a march on the courthouse in Selma but also similar actions in ten rural counties as well as an investigation of local restaurants and hotels to determine if they were now open to blacks as the 1964 Civil Rights Act required. King himself planned to request a room at the Hotel Albert, an Italian-like palace built by slaves. And black workers would apply for city jobs reserved for only whites to see if the city’s government still used discriminatory hiring practices.12

The day after King announced the expanded agenda for Freedom Day was the reverend’s thirty-sixth birthday, and he was happily surprised when Lyndon Johnson telephoned to congratulate him and express enthusiasm for voting rights. “[It] will answer [most] of your problems,” he told King. “There’s not going to be anything . . . as effective as all of them voting.”

“That’s right,” King replied.

Johnson ran through some possible options for how the federal government could help to reform voting registration in the South. “No tests on what Chaucer said or Browning’s poetry or constitutions. . . . We may have to put [voter registration] in the post office. Let the postmaster [do it]. That’s a federal employee that I can control. . . . If he doesn’t register everybody, I can put a new one in. . . . They can all just go to the post office like they buy a stamp. . . . I just don’t see how anybody can say that a man can fight in Vietnam but he can’t vote in the post office.” No politician, wherever he lived, could ignore the interest and desires of people who could vote.

Johnson also offered some specific suggestions about how King and his fellow activists could get the American people on their side. The president suggested that the best way to build public support was to find the worst example of “voter discrimination where a man got to memorize Longfellow or . . . quote the first ten amendments . . . and if you just take that one illustration and get it on the radio, and get it on the television, and get it in the pulpits . . . pretty soon, [ordinary Southerners] will say, ‘That’s not right. That’s not fair.’”

For his part, King reminded Johnson of the political advantages the president stood to gain from helping black southerners to cast their votes freely. “The only states you didn’t carry in the South [in 1964] . . . have less than 40 percent of the Negroes registered to vote,” King told the president. “It’s so important to get Negroes registered to vote in large numbers in the South. It would be this coalition of the Negro vote and the moderate white vote that will really make the new South.” King’s message was unmistakable: if Johnson could ensure that black southerners were able to register and vote, their resulting support at the polls would give him tremendous political power.

“That’s exactly right,” Johnson said. But then, having raised King’s hopes that he would move swiftly to shore up African Americans’ voting rights, he dashed them. His first priorities, he said, remained aid to education, the war on poverty, and Medicare. “We’ve got to get them passed,” Johnson told King, “before the evil forces concentrate and . . . block them.” Once these goals were accomplished, he could turn to voting rights. For the already-harried King, who had been intending for the upcoming Freedom Day demonstrations to inspire action in Washington, the president’s remarks could not have been more poorly timed.13

WHILE KING WAS PLANNING FOR FREEDOM DAY, HIS ADVERSARIES HAD been making preparations of their own. Wilson Baker, the newly appointed public safety director for Selma, had been carefully considering his options about how to direct the official response to Freedom Day. Baker knew that King would be powerless without a violent—and well-publicized—confrontation with segregationist forces that would capture the public’s attention and pressure Congress and President Johnson to act. Baker hoped to emulate Laurie Pritchett, the affable police chief of Albany, Georgia, who, after studying the reverend’s tactics, had decided to respond nonviolently when King came to Albany in December 1961. The chief treated demonstrators with civility, and when King himself was jailed for parading without a permit and similar charges, he ordered the cell cleaned and supplied his prisoner with a radio and plenty of reading material. “We killed them with kindness,” said an Albany official after King’s campaign there had failed and he had left the city. Baker hoped to achieve the same result in Selma. For his plan to work, however, he would need Sheriff Jim Clark to cooperate. So Baker and Mayor Joseph Smitherman met with Clark and managed to persuade him to control himself and his posse during the Freedom Day demonstrations.14

As it turned out, Freedom Day was more of a success for Baker than it was for King. The public safety director met King and four hundred volunteers as they walked to the courthouse on the cold Monday morning and warned them that if they didn’t rearrange their ranks he would arrest them for parading without a permit. King complied. At the courthouse, where Clark claimed jurisdiction, they found the sheriff awaiting them, billy club at the ready. But Clark only led the group to an alley where they were told to wait for the registrar to summon them. They had waited for several hours “feeling like caged rats,” Abernathy recalled, when King decided to visit the Hotel Albert to see if he could become the first Negro to rent a room. Abernathy, John Lewis, and Wilson Baker also went along to observe this potentially historic event.

He was received cordially at the luxurious hotel, but then a muscular white youth suddenly pushed Abernathy aside and punched King in the head. When King fell to the floor, the youth kicked him in the thigh. John Lewis grappled with the man, and Baker quickly subdued and arrested him. He was Jimmy George Robinson, a member of the fanatical National State Rights Party, which had come to Selma to harass King.

Abernathy and Dorothy Cotton, King’s secretary, helped him to his feet. He appeared unharmed but stunned, so aides hurried him to his room. “He packs a pretty good wallop,” King said, mopping the sweat off his face and sipping a can of beer. Mrs. King later said that her husband complained of “a terrible headache” that lasted several days.15

That night King told his advisers to increase the pressure. On Tuesday, January 19, fifty volunteers would refuse to stand in the alley, hoping that would produce the violent incident that would arouse the conscience of the nation. If not, they might have to try a new approach, such as moving to other nearby cities like Marion or Camden, where not a single black was registered. The fight for Selma, it appeared, was faltering.

WILSON BAKER MUST HAVE FELT GOOD AS HE PREPARED FOR BED ON Monday night. His strategy was working. Any satisfaction, however, surely evaporated when he received a call from Mayor Smitherman. Come to the county jail now, the mayor told Baker. There was trouble.16

It was Clark. The sheriff had become unhinged, telling Baker that he was “giving the city away to the niggers” and that his posse was about to mutiny. Tomorrow he would arrest “every goddamned” demonstrator who came to the courthouse, Baker remembered him saying. Baker and Smitherman pleaded with him to remain cool for just a few more days, but the angry sheriff would not listen.17

On Tuesday morning Clark got his revenge. When sixty-seven marchers arrived at the courthouse, he ordered them to take their places in the alley, and when they refused, he arrested them all on charges of unlawful assembly. Amelia Boynton, long a thorn in his side, received harsher treatment than did her comrades. While Clark’s men corralled the other demonstrators, the sheriff dragged Boynton down the street to a waiting police car. The other demonstrators called out to her, “Go on, Mrs. Boynton, you don’t have to be in jail by yourself, we’ll be there.” Pointing to reporters and cameramen, she told Clark, “I hope the newspapers see you acting this role.” Clark replied, “Damnit, I hope they do.” And they did. The following day, in their coverage of the day’s events, the New York Times and the Washington Post featured a front-page photograph of Clark manhandling Boynton.18

At the police station Boynton was charged with criminal provocation. Clark later claimed that she had ordered the marchers “to take over the offices and to . . . urinate on top of the desks and throw the books on the floor.” She was fingerprinted, photographed, and thrown into a cell, where she sat alone, feeling like a common criminal. Then she heard the demonstrators arriving in the jail: the old walking with difficulty up the stairs, the young skipping, everyone singing loudly. As they passed her cell, one said, “I told you we would be here with you,” and Boynton immediately felt better.19

By the end of the day the demonstrators were freed thanks to the efforts of SCLC lawyers, who came to Selma to arrange for their release. Boynton and the others were honored that night at a rally at Brown Chapel, where Reverend Abernathy recommended that the Voters League make Sheriff Clark an honorary member of their group in recognition of everything he was doing to publicize their struggle to vote. The audience agreed enthusiastically.20

The demonstrations and arrests continued on Wednesday and Thursday, but Friday, January 22, was an unforgettable day for Selma’s black community. It began first as a rumor, then by late afternoon rumor became fact as the news spread like wildfire: “The teachers are marching! The teachers are marching!” They were indeed: 105 black men and women—nearly every teacher in Selma—dressed impeccably, with the women wearing “flowery hats and gloves” and the men in “somber colored suits and hats,” the journalist Charles Fager later recalled. Many were happily waving toothbrushes, signaling their commitment to spend the night in jail if necessary. Their students and parents cheered and wept as the teachers strode confidently down Sylvan Street to the courthouse. “This is bigger than Lyndon Johnson coming to town!” exclaimed one black reporter.21

Leading the teachers were the Reverend Frederick Reese, a science teacher and president of the Dallas County Voters League, and Andrew J. Durgan, the new president of the Selma Teachers’ Association. Earlier that week Reese had written the Board of Registrars, asking them to open their office, usually closed on Friday, but the Board refused: to do so would violate Alabama law, they claimed. Reese was himself registered, but many of his colleagues, including some with advanced degrees, had been repeatedly rejected without cause. He had asked them over and over, “How can you teach citizenship [when] you’re not a first-class citizen yourself?”

Never in the history of the movement in Alabama had teachers participated in such numbers. Economically, they had the most to lose from speaking out, much less joining a demonstration; the members of the local school boards that employed them and the superintendents who supervised them were white men capable of firing them for the slightest infraction. And sure enough, as Reese and the others approached the courthouse steps, there stood Joseph Pickard, the superintendent of schools, and Edgar Stewart, chairman of the Selma School Board. Stewart warned them that entering the courthouse was illegal. “You are in danger of losing all of the gains you have made,” he said. Reese thought this ridiculous. After all, people entered the courthouse every day to pay their taxes, and the building belonged to the teachers as much as it did to Jim Clark and the chairman of the school board. “We want to see for ourselves if the Board is open,” Reese said, and by twos, the teachers climbed the steps to the courthouse door.

As the teachers approached it, the glass door swung open, and Clark and five deputies appeared. “You can’t make a playhouse out of the corridors of this courthouse,” the sheriff yelled. He gave the teachers one minute to leave. Suddenly the door opened again, and Blanchard McLeod, the circuit solicitor, pulled Clark back inside, leaving his men behind. A moment later Clark returned and again ordered them to move back. A deputy began counting off the seconds. Then the sheriff and his deputies moved forward, their billy clubs forcing the teachers back down the stairs. Clark and his men returned to the courthouse door, but turning around, again found themselves facing Reese and his colleagues. Stewart warned them off. “The sheriff is custodian of this courthouse,” said the school board chairman, “and he has been most forbearing.” Stewart urged them to retreat. They did not, and again Clark and his men pushed them down the steps.

At that moment Reese realized that Solicitor McLeod must have told Clark not to jail Selma’s teachers and that Clark, perhaps fearing that the teachers’ incarceration would have left young black children free to run wild in the streets, was obeying. Without the possibility of arrest and without being able to enter the courthouse peacefully, the demonstrators were stymied. So Reese and his colleagues turned around and marched to Brown Chapel, where they received a hero’s welcome. “The place erupted into a tumultuous cacophony of cheers and applause,” said one observer, “an ovation that continued until the last of the [teachers] had assembled around the pulpit. Behind them veteran civil rights workers wept at the spectacle and teachers and students both joined them, the teachers overcome by a wave of self-respect and unrestrained admiration from their students that they had never experienced before.” Andrew Young called the day “the most significant thing that has happened in the racial movement since Birmingham.”22

Although the teachers’ march and the demonstrations preceding it were emotionally satisfying, they had accomplished little in the way of advancing the movement’s goals. More than two thousand protestors had been arrested, but not a single person had been registered to vote. Nor had Clark’s brutality moved the president to announce that he would soon be submitting a new voting rights bill to Congress. In order to appease King and alleviate some of the pressure he was feeling from civil rights activists, the president had already mentioned such an initiative in his State of the Union message on January 4, but he buried it under an avalanche of other proposals. Adding to the sense of stagnation was federal judge Daniel Thomas’s temporary order, released on January 23, the day after the teachers’ march. Thomas’s order restrained Dallas County officials like Jim Clark from interfering with voter registration. This was not, however, the victory for the movement that it seemed. Although his order was aimed at Clark, Judge Thomas also blamed civil rights workers for the disruptions that had occurred. Frustrations were intensifying on both sides.23

Annie Lee Cooper, for one, was losing patience. The fifty-three-year-old Alabamian had no trouble voting when she lived in Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, but when she returned to Selma in 1962 to care for her ailing mother, she became a second-class citizen. She tried to register several times, including one fateful day in 1964. While waiting in a long line at the courthouse, she was spotted by Dr. Dunn, owner of the nursing home where Cooper worked and a diehard segregationist. Dunn was jotting down the names of would-be registrants in a notebook, and he glared at Cooper when he saw her. The next day he fired her. Eventually she got another job as night manager at Selma’s Torch Motel—and continued her efforts to register.24

On Monday, January 25, Cooper joined the protestors in line at the courthouse, again hoping to register. As she waited, she heard a noise behind her—a policeman was beating an activist. Cooper moved for a better look, then cried out, “He’s kicking him!” A woman nearby told her to be quiet. “We’re not in slavery time here,” Annie Lee Cooper replied. “Nobody’s afraid of them.”

Suddenly Sheriff Clark appeared and pushed Cooper with a force that almost knocked her down. “Don’t jerk me like that,” she snapped. Clark backhanded her. She reared up and punched Clark in the eye, then punched him again. Stunned, Clark fell back and yelled to his deputies nearby, “You see this nigger woman! Do something!” One grabbed her from behind, but she continued to resist until she was free. She again lunged at Clark, hitting him a third time.

At 220 pounds, Cooper’s blows nearly had the sheriff on the ground. It took three deputies to subdue and handcuff her. But she had enough strength left for one final taunt: “I wish you would hit me, you scum,” she yelled at Clark. The sheriff, now disheveled, his cap, tie, and badge torn away during the struggle, whacked her on the head with his club, the impact making a drumlike sound that reverberated down the street.

Clark himself drove Cooper to jail, on the way repeatedly asking, “How much is that damned Martin Luther King paying you?” She spent eleven hours in a cell, nursing her wounds and singing spirituals while Clark drank himself into a stupor. Near midnight the jailer, fearful that the drunken sheriff might actually kill her, let her go.

Clark’s brutality had given the movement the opening it had been waiting for. The next morning the New York Times ran a photograph on its front page showing Mrs. Cooper being held on the ground by two deputies while she and Sheriff Clark grappled for his billy club. Yet the incident prompted no national outcry, and signals from Washington were discouraging. King had heard nothing from Johnson after his birthday phone call, and there had been no mention of a voting rights bill in the president’s inaugural address on January 20. There were only vague press reports that the Justice Department was preparing a constitutional amendment prohibiting literacy tests, but its passage was far off and uncertain. Worse still, the New York Times was reporting that the movement in Selma had reached a dead end.25

King’s top aides decided that it was time to up the ante. The reverend himself must go to jail. If that didn’t produce the crisis King needed, the movement would go to Perry and Wilcox Counties, where blacks lived under conditions that approximated slavery and white officials were even more brutal than Clark. “It was midnight in Selma,” King told his followers on January 31. They would do whatever was necessary to secure the right to vote. “If Negroes could vote,” he told his audience, “there would be no Jim Clarks, there would be no oppressive poverty directed against Negroes, our children would not be crippled by segregated schools, and the whole community might live together in harmony.” In order to make that vision a reality, he would march with them in the morning.26

It was bitterly cold on the morning of February 1, 1965, so King and more than 260 of his followers donned coats, hats, and muffs for the march from Brown Chapel to the courthouse. They walked together down the center of Sylvan Street, and Wilson Baker quickly arrested them for parading without a permit. Most were released on bond later that day, but King and Ralph Abernathy declined and remained imprisoned in an eight-foot cell. In addition to fasting, praying, and reading the Bible, King also drafted orders for SCLC executive director Andrew Young, designed “to keep national attention focused on Selma.” Baker visited the reverend in jail to express concern about the children who had just joined the demonstrations and were being arrested. Because the jail was overflowing, the children were being sent to state prison farms. King told him that they deserved to “make witness” too.27

King’s arrest produced front-page headlines in the nation’s most prominent papers, and the three television networks covered it. More journalists hurried to Selma. Fifteen congressmen from New York, Michigan, and California, sympathetic to the cause, also announced that they would soon meet with King. Governors sent messages of support. Even President Johnson, who had lately been so reticent about the voting rights struggle, told a press conference, “All of us should be concerned with the efforts of our fellow Americans to register to vote in Alabama. I intend to see that the right [to vote] is secured for all our Americans.” But, Johnson added, he would use the authority he already possessed under existing laws; he said nothing about the possibility of new legislation to guarantee black voters’ rights.28

The movement seemed to have won another victory on February 1, when Judge Daniel Thomas issued a judicial order that appeared to solve the Selma problem. Henceforth, city and state officials must stop harassing those who wished to register, the judge commanded. The complicated test of an applicant’s knowledge of government would also be eliminated. Registrars must process at least one hundred applicants on the days they were open, and everything must be completed by July 1. Failure to do so would result in a federal registrar being brought to Selma.29

Judge Thomas’s order created confusion in King’s camp. Although the order eliminated many of the obstacles to black voters in Selma, it still left the registration process in the hands of local officials at the courthouse run by Clark, who was sure to thwart any black applicants’ attempts to register. Andrew Young was disappointed and said that demonstrations would continue. By way of explanation, he added, “We are so emotionally caught up in the moment that it is hard for us to be objective. We feel that we can have very little faith in this unless something is done about Jim Clark.” Asked for King’s response, Young said, “He would like to think about it overnight.” But as a sign of good faith, Young canceled the demonstrations scheduled for that day.30

King was angry and criticized Young’s decision to halt the demonstrations. “Nothing has been done to get Judge Hare’s injunction dissolved,” he wrote Young. “Nothing has been done to clear those who were arrested. . . . Also please don’t be too soft. We have the offensive. . . . In a crisis we must have a sense of drama. . . . We may accept [Thomas’s] order as a partial victory, but can’t stop.” The marches resumed.31

On Friday, February 5, four days after King’s arrest, the New York Times ran “A Letter from MARTIN LUTHER KING from a Selma, Alabama, Jail.” It read, in part,

By jailing hundreds of Negroes, the city of Selma, Alabama, has revealed the persisting ugliness of segregation to the nation and the world. When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed many decent Americans were lulled into complacency because they thought the days of difficult struggle were over.

Why are we in jail? Have you ever been required to answer 100 questions on government . . . merely to vote? Have you ever stood in line with over a hundred others and after waiting an entire day seen less than ten given the qualifying test?

THIS IS SELMA, ALABAMA. THERE ARE MORE NEGROES IN JAIL WITH ME THAN THERE ARE ON THE VOTING ROLLS.

[sic]

. . . [M]erely to be a person in Selma is not easy. When reporters asked Sheriff Clark if a woman defendant was married, he replied, “She’s a nigger woman and she hasn’t got a Miss or a Mrs. in front of her name.”

“This is the U.S.A. in 1965,” King concluded. He asked for the nation’s support, which, he said, not even “the thickest jail walls can muffle.”32

The power of King’s statement, modeled after his more celebrated “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” was weakened when reporters noticed that, in fact, King was out of jail by the time the letter was published. His advisers urged him to hold a press conference to address the timing of the letter and the circumstances of his release, but he had nothing new to say. Someone suggested that King could explain that he had left jail to prepare for a meeting with President Johnson to discuss a new voting rights law. After that alibi was approved, King’s lawyer Harry Wachtel hurriedly contacted the White House, only to find that officials there were not receptive to a King visit. Johnson, erratic as ever, flew into a rage at the request. “Where the hell does King get off inviting himself to the White House?” he asked an aide. Also annoyed was Acting Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, who had hoped that Thomas’s order would end the demonstrations and silence the calls for a voting rights bill; indeed, Katzenbach had urged Thomas to issue his order and now was exasperated that it hadn’t had the intended effect. “They’ve gotten about everything they wanted,” he told Johnson. “But they’re still demonstrating. . . . And they’ve got these kids whipped up there.”

Rather than meeting with King, Johnson preferred the idea of a cooling-off period to see if Thomas’s order would solve the problems. Johnson realized that Clark’s actions had the potential of creating sympathy for the movement, thereby making it easier for Johnson to justify his defense of voting rights. However, he also feared that if Clark went too far, it might provoke a black riot, creating a white backlash that would doom King’s efforts. In short, Johnson wanted King to give Thomas’s order a chance and stop pressuring him to submit a voting rights bill immediately. “I was determined not to be shoved into hasty action,” Johnson later observed.33

Johnson hated to be shoved, but he also knew that he needed King as much as the preacher needed him. Although the president feared the political repercussions of supporting a voting rights bill, he also took pride in his recent achievements in civil rights and knew that the reverend would be a crucial ally in helping to push through another historic piece of legislation similar to the 1964 Civil Rights Act. But Johnson had a more immediate, pressing need for King’s help as well. King was the only brake on a civil rights movement that often seemed on the verge of anarchy, and if King failed to keep the movement unified, a possible successor was waiting in the wings.

While King had been in jail, Malcolm X had made a surprise visit to Selma and, at SNCC’s invitation, addressed a rally at Brown Church. Even though the radical Muslim minister and activist had once called King “a little black mouse,” a recent pilgrimage to Mecca had opened his eyes to the possibility of interracial brotherhood. He was beginning to temper his philosophy of black supremacy; however, the message he delivered in Selma was still much more menacing than King’s. “I think the people in this part of the world would do well to listen to Dr. Martin Luther King,” Malcolm X said, “and give him what he’s asking for and give it to him fast before some other factions come along and try to do it another way.” Privately he told Coretta Scott King that he hadn’t come to Selma to make King’s life harder; in fact, the opposite was true. He thought his very presence on February 4 would scare white people into King’s arms. Within a few hours of their conversation Malcolm X was gone. Two weeks later he would be assassinated while preparing for a speaking engagement in Manhattan.

Malcolm X’s brief appearance in Selma may have had the effect he intended, for two days later Johnson reversed himself. On Saturday, February 6, a slow news day, Press Secretary George Reedy announced that the president planned to urge Congress to enact a voting rights bill during that session and that Vice President Hubert Humphrey and Acting Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach would meet with King on Tuesday, February 9. Privately, King was informed that he might be able to see the president as well if the chance arose, but for now, that possibility must be kept secret. If the news leaked, there would be no meeting with Johnson.34

On Tuesday, while President Johnson was secluded with his national security team discussing whether to commit American ground troops to defend South Vietnam, King sat anxiously in Vice President Humphrey’s office, hoping for a few minutes with Johnson. He had made it clear to Humphrey, Katzenbach, and other Justice Department lawyers assembled that a new voting rights bill should mandate an end to literacy tests and the creation of federal registrars appointed by the president to guarantee that the federal voting laws laid out in the Fifteenth Amendment, the Civil Rights Act, and elsewhere would be applied fairly in all elections—local, state, and national. The vice president expressed doubt that such a bill could pass at present, and neither he nor Katzenbach endorsed King’s recommendations.

Finally, after ninety minutes passed, Humphrey’s phone rang, which was the signal to sneak King into the Oval Office. King and Johnson met for only fifteen minutes, but the president seemed more receptive than Humphrey did to a bill that eliminated literacy tests, applied to all elections, and was backed up by federal registrars. Leaving the White House, King told reporters that the meetings had been “very successful.” Privately, King was less confident. Given Johnson’s volatile temperament—one day warm and supportive, the next cold and distant—it was impossible for King to know precisely where the president stood. An even greater effort would be required to get the administration to transform its statements into action.35

King returned that night to a sea of troubles in Selma. The movement there was exhausted, its leaders divided over how next to proceed. Judge Thomas’s order had called for the creation of an “appearance book” that those seeking registration could sign when the Board was in recess. The applicants who signed the book would then receive a number that allowed them to be served first when the Board met again. Local leaders like Reverend Reese, who had led the schoolteachers’ march, supported the move, whereas the fiery Jim Bevel denounced it as “a white man’s trick,” a ploy designed to obstruct registration. Their conflict reflected deeper tensions among the movement’s various groups: the Selma activists who for decades had been fighting for voting rights and saw Thomas’s order and the appearance book as positive signs; the young men and women of SNCC who often accused King of being a celebrity who went briefly to jail, settled for symbolic settlements of deep-rooted grievances, and then moved on while local activists repaired the wreckage left in his wake; and the ministers and other organizers of SCLC who saw the voting rights issue as part of a larger struggle for black emancipation that could be achieved only with federal assistance. Ironically, the more that the registration process improved, the more it threatened King’s movement by placating local activists and sapping their energy for the broader fight for civil rights.36

While King had been busy with Johnson, Bevel had led sixty demonstrators to the courthouse, where they refused to sign the appearance book. “You’re making a mockery of justice!” screamed Sheriff Clark. Out came the billy club, and Clark jabbed Bevel down the courthouse steps, then arrested him. The jabbing turned into a beating that continued even as five deputies dragged Bevel to jail. Bevel fainted and drifted in and out of consciousness. When he awoke he was wet and freezing: Clark’s men had turned a fire hose on him and left the windows of his cell open on this cold February day. When Bevel’s colleagues eventually located him, he was under armed guard and chained to his bed. They called a doctor, who examined Bevel, diagnosed viral pneumonia, and immediately ordered him moved to a hospital.37

Bevel’s fellow protestors continued to be brutalized. On Wednesday, February 10, the day after King’s meeting with Johnson, 161 students picketed the courthouse with signs that read, “Let Our Parents Vote” and “Jim Clark Is A Cracker.” By the afternoon Clark had had enough: if the kids wanted to march, he would oblige them. Charging them with truancy, he and his posse forced them to run three miles along a road that took them out of town. Those not fast enough received shocks from the posse’s cattle prods. Those who fell back were beaten with billy clubs. Some vomited and collapsed in a nearby gravel pit. When one of those students, Letha Mae Stover, looked up from where she had fallen, she faced an officer who forced her to rise by continually jabbing her in the back. If she wanted to march, he said, he would show her how. Exhausted and unable to take another step, she told him that he might as well kill her, because she couldn’t get up. The officer turned away to pursue others trying to escape.38

Wilson Baker was furious. For weeks he had warned the mayor that Clark was “out of control,” playing into the hands of the civil rights activists. If Clark attacked any other children, Baker said, he would arrest him. Clark ignored such threats. Returning to town, he happily told reporters—who had been blocked from observing his latest atrocity—that because the jail was filled, he was just escorting the young folks to a comfortable lodge owned by the Fraternal Order of Police. A journalist asked Clark whether he had used cattle prods on the children, to which Clark replied, “Cattle prods? I didn’t see any.” It was a bald-faced lie. In addition to the word of the many students who had endured the abuse, an FBI agent who observed the event (but did nothing to stop it) later testified to seeing “four or five or six instances” of Clark’s men shocking the students with cattle prods.39

That night King held a strategy session with his top aides. King himself thought that the demonstrations in Selma had run their course and that SCLC should now move on to more fertile territory, like Lowndes County, or as it was better known to civil rights veterans, “Bloody Lowndes.” Of the almost six thousand blacks who were eligible to vote there, not a single one had ever tried to register. “You should not only know how to start a good movement,” King said, “[you] should also know when to stop.” SCLC should “make a dramatic appeal” in Lowndes or some other equally embattled county.

King’s colleagues agreed. Ironically, Selma had proven to be less hostile than they had expected, a fact typified by the clashes between Clark and Baker. Further, some considered Judge Thomas’s rulings to be a good-faith effort to accelerate the registration process. King and SCLC were after bigger game than what they thought could be found in Selma: they wanted a change that would affect not simply Alabama but the entire South.40

Selma’s white elites were indeed divided over Sheriff Clark’s outrageous behavior. Selma’s political and business establishment felt that Clark’s actions reflected poorly on their community and jeopardized the northern investments on which the city’s economy depended. Because of this, they had begun to criticize him openly. Roughing up an outside agitator like Jim Bevel was one thing; attacking children, even if black, was quite another, they contended. The editor of the Selma Times Journal, a prominent member of the White Citizen’s Council, weighed in, attacking Clark’s viciousness and demanding that it cease.

The sheriff read everything written about him, and the criticism deeply hurt him—so much so that his angst began to manifest itself physically. Early on the morning of February 12 a sleepless Clark complained to his wife of chest pain and was quickly admitted to Vaughn Memorial Hospital. “The niggers are givin’ me a heart attack,” he cried, although medical tests later found no such condition. When young activists—many of them casualties of Clark’s march—learned of his illness, they hurried to the hospital where, as a gentle rain fell, they knelt in prayer, beseeching God to heal their nemesis. Some carried signs that read, “We Wish Jim Clark A Speedy Recovery.” “It just wasn’t the same without Jim Clark fussing and fuming,” one of the demonstrators later told a reporter. “We honestly miss him.”41

Clark recovered quickly and was on duty when the Reverend C. T. Vivian led a group of aspiring voters to the courthouse on February 16. Vivian, one of King’s key lieutenants, personified the modern civil rights movement: he had desegregated a cafeteria when he was twenty-three; learned nonviolence from Jim Lawson like his fellow seminary students, John Lewis and Bernard Lafayette; and joined the Nashville sit-in movement and the Freedom Rides. Tough and determined, Vivian wasn’t afraid of Jim Clark, and his boldness would soon rejuvenate the movement in Selma.

Arriving at the courthouse with his group, Vivian found about one hundred would-be voters already waiting in line. Soon it began to rain, and he sought shelter for them inside the courthouse. The door was locked: Clark had seen them coming and made sure they couldn’t get in. They stood under an overhang and sang freedom songs. Apparently the singing annoyed the sheriff, because his deputies opened the door wide enough for him to yell at Vivian. Network TV cameramen moved in to capture the confrontation.

“Turn that light out,” Clark screamed at the cameramen. “You’re blinding me and I can’t enforce the law with a light in my face.”

Vivian seized the moment. “We have come to register,” he said. Then, as the cameras rolled, Vivian launched into a philosophical discussion of evil that ranged from Hitler’s Germany to Clark’s Alabama. To the deputies, Vivian said, “There were those who followed Hitler like you blindly follow this Sheriff Clark, who didn’t think their day would come, but they were pulled into a courtroom one day and were given death sentences. You’re not that bad a racist but you’re a racist in the same way Hitler was a racist. . . . You can’t keep anyone in the United States from voting without hurting the rights of all other citizens. Democracy is built on this.”

Clark was near the breaking point. His deputies told him to return to his office, assuring him that they would handle the situation. Clark turned away, but Vivian didn’t stop: “You can turn your back on me but you can’t turn your back on justice.” Suddenly Clark whirled and punched Vivian in the mouth with such force that he fractured a finger. The minister fell back down the steps but got up shakily, his face bloody. “What kind of people are you?” he asked Clark and the others. “What do you tell your children at night? What do you tell your wives at night? . . . We’re willing to be beaten for democracy, and you misuse democracy in this street. You beat people bloody [so] they will not have the privilege to vote. . . . We have come to register to vote.”

Sheriff Jim Clark seizes C. T. Vivian, King’s aide, during a demonstration on February 16, 1965. After Clark punches him in the mouth, Vivian asks Clark and his deputies, “What kind of people are you?” © BETTMAN/CORBIS

“Arrest him now!” Clark ordered, and Vivian was taken away. That evening the confrontation aired on national television. “Every time it appears that the movement is dying out,” said a King aide, “Sheriff Clark comes to our rescue.”42

Vivian’s lip had been split in the assault, but he was undeterred. After his release from jail he quickly answered Albert Turner’s call to come to rural Marion, an outpost of activism, to preach at Zion’s Chapel Methodist Church. Turner, a bricklayer and local civil rights leader, had been born in a shack in Perry County, of which Marion was the seat. His father had been a share-cropper, but Turner himself had escaped poverty, attending Alabama A&M. When he returned home after college he was depressed to find so many black residents of Marion, himself included, unable to vote. “I always thought I was a pretty good student,” he later said, “and it . . . was an affront to me that these dummies who were the registrars were saying to me that I couldn’t pass [their] test and they couldn’t hardly write their names. . . . [T]hat built up and built up . . . and people became angry and I did myself.” Just 150 of Marion’s black residents were registered out of an eligible population of over 5,000—a fact that Turner was determined to change.

In 1962 Turner organized the Perry County Voters League, an organization dedicated to helping people register and pass the extraordinarily complicated registrar’s test. But most applicants still failed, including a twenty-six-year-old Army veteran named Jimmie Lee Jackson and his grandfather, Cager Lee. Both had tried to register five times but were consistently rejected. “I been here a long time and I ain’t never voted,” Lee once told Turner. “You say it’s time I did; I say I’m ready.”

Turner had welcomed King’s coming to Selma, and was soon joined in Marion by SCLC’s James Orange. They created voter workshops and organized demonstrations. When Vivian arrived in the city on the night of Thursday, February 18, a black boycott had crippled local business, and Orange was in jail, charged with multiple counts of contributing to the delinquency of a minor after he led 700 students on a protest march around the county courthouse. At the conclusion of his address at Zion’s Chapel Methodist Church that night, Vivian departed through a rear exit and left Marion, a move that may have saved his life. The congregation, numbering about 450, planned to march on the jail to serenade Orange with freedom songs.43

Night marches were always potentially dangerous for demonstrators because darkness gave their enemies a better chance to waylay them and flee, but Turner and the others were surprised to see what awaited them when they left Zion’s Chapel Methodist Church. Arrayed before them were more than two hundred angry law enforcers—including Marion police, Perry County deputy sheriffs, and one hundred state troopers dressed in riot gear—as well as townspeople brandishing clubs. State officials believed that the activists planned to break into the jail to free Orange.44

Nearby the horde was Sheriff Jim Clark, tonight casually dressed and without his usual helmet but nevertheless armed with a nightstick. “Don’t you have enough trouble of your own in Selma?” asked a reporter.

“Things got a little too quiet for me . . . tonight, and it made me nervous,” he replied. Some wondered if Vivian’s presence explained Clark’s appearance in Marion. Indeed, both Turner and Vivian later concluded that state troopers planned to kill Vivian in retribution for his earlier confrontation with the sheriff.45

Television reporters and photographers, who had been capturing the images of Clark’s brutality and broadcasting them on the networks’ evening news programs, were another target of the law enforcers’ wrath. When NBC News’s Richard Valeriani and his crew arrived in Marion, they received a very unpleasant welcome. Townspeople cursed them, and some sprayed their cameras with paint. Local police quarantined Valeriani and other journalists and photographers near city hall to prevent them from observing events. The cameramen turned their lights on anyway, hoping to photograph the march, but then an officer yelled, “Turn those goddamned lights off!” They did.46

When Turner and the other marchers appeared outside Zion’s Chapel Methodist Church, Marion police chief T. O. Harris stepped forward and told them to return to their church or face arrest for unlawful assembly. Turner’s colleague, the Reverend James Dobynes, asked Harris, “May we pray before we go back?” and he knelt. However, the only answer he received were blows from state troopers. He cried, “Jesus! Oh Jesus! Have mercy.” The troopers ignored his pleas, grabbed his arms and legs, and dragged him away. That seemed to be a signal to the other officers and townspeople, because suddenly the streetlights went out and the mob attacked demonstrators and reporters alike. From his vantage point John Herbers of the New York Times observed “state troopers shouting and jabbing and swinging their nightsticks. The Negroes began screaming and falling back around the entrance of the church.” Their proximity to a place of worship didn’t prevent the troopers and other officers from kicking and beating them. Others fled to the nearby Tubbs Funeral Home, but the troopers followed and beat whomever they could get their hands on. Screams and the sound of clubs hitting bodies echoed through the town square.47

When United Press International photographer Pete Fisher snapped a picture of the mayhem, someone behind him hit him on the head with a nightstick. Fisher ran toward city hall but never made it. A group of men surrounded him, slapped him, and destroyed his camera. His assailants left Fisher, but a few minutes later another man, Woodfin Nichols, accosted him. Nichols, a grocer, punched Fisher in the face repeatedly until the chief of police stopped Nichols and sent him on his way. A deputy sheriff attacked Reggie Smith, another UPI photographer, and jabbed him in the ribs and smashed his camera. Local police stood by silently while Fisher and Smith were attacked and other reporters called for help.48

One of Pete Fisher’s attackers approached NBC’s Richard Valeriani and asked, “Who invited you here?” Valeriani moved away but then felt a severe blow to the back of his head. To the Times’s John Herbers, the impact sounded “like a gourd being hit with a baseball bat.” A state trooper took a blue axe handle out of the hands of Sam Dozier, a lumber salesman. Tossing the club away, the trooper told Dozier, “I guess you’ve done enough damage with that tonight.” Dozier fled, and the trooper walked away without offering help to the injured journalist.

Dazed and held upright by his cameraman, Valeriani touched the back of his head and found his hand covered with blood. Another man approached him and asked, “Are you hurt, do you need a doctor?”

“Yeah, I think I do,” Valeriani replied, appreciating the man’s concern. “I’m bleeding.”

The man looked Valeriani in the eye and said, “Well, we don’t have doctors for people like you.” Only when someone from city hall offered to take Valeriani to the hospital did he receive treatment for his head wound.49

Eighty-year-old Cager Lee, who wanted to vote at least once before he died, was one of the last to leave the church through its rear exit. Walking around to the side he saw a crowd of white townspeople milling about. One approached him and said, “Go home, Nigger. Damn you, go home.” Lee said nothing, and, at five feet and 120 pounds, posed no threat, but the man struck him on the head anyway. Lee fell to the ground. When he tried to get up the vigilante kicked him twice in the back. “It was hard to take for an old man whose bones are dry like cane,” Lee later told a reporter. One of his assailants recognized Lee, which may have saved him from a worse beating. “God damn, this is old Cager. Don’t hit him anymore,” he said, then helped him up.50

Lee paused to catch his breath, then went to Mack’s Cafe, where he found the rest of his family: his grandson Jimmie Lee Jackson, Jackson’s mother, Viola, and sister, Emma Jean. Jackson, seeing the bloody cut on Lee’s head, exclaimed, “Grand-daddy, they hit you! Come on out of here and let me carry you to the hospital.”

As they started to leave, state troopers burst into the café, overturning tables, smashing lamps, and hitting black patrons. Norma Shaw, the manager of the café, yelled at them, “Y’all ought to be ashamed of yourselves. These folks not doing anything [sic].” The troopers hit Shaw with their billy clubs, searched through her purse and, finding a gun, arrested her, and dragged her away to jail without shoes or a coat.

What happened next is unclear. Some eyewitnesses later claimed that a trooper clubbed Viola Jackson and threw her to the floor. Her son rushed the trooper but received a punch in the face while another threw him against a cigarette machine. A third trooper, James Bonard Fowler, drew his service revolver and calmly shot Jimmie in the stomach. Fowler later claimed that Jackson attacked him with a beer bottle and tried to seize his gun, causing him to fire in self-defense.

Although seriously hurt, Jimmie staggered outside, running a gauntlet of troopers who yelled, “Get that nigger.” A deputy sheriff ran after him, hitting him on the head until he collapsed. Jackson lay on the ground for half an hour until an ambulance picked him up and took him to Perry County Hospital for treatment. “I have been shot, don’t let me die,” Jackson mumbled as he lay on a stretcher waiting for a doctor to appear. Eventually he was treated for a scalp laceration and a gunshot wound, but because he needed surgery and the facility lacked a blood bank, physicians decided to move him to Good Samaritan Hospital in Selma. Robert B. Tubbs, the owner of Tubbs Funeral Home, drove Jackson the thirty miles to Selma; he later told FBI agents that Jackson repeatedly said, “Lord, save me.” It was almost midnight when Jackson was admitted to Good Samaritan, more than two hours since the shooting, and he was now in critical condition. Grimacing with pain, Jackson told a doctor that an Alabama state trooper shot him while he was trying to defend his mother, who was being beaten. One nurse who examined him did not expect him to survive, saying later that “his insides are torn up and his body is infected.”51

Martin Luther King was in Atlanta suffering from a bad cold when he received news of the Marion tragedy later that night. He immediately wired the Justice Department asking for help, but Katzenbach, who the president had finally elevated to Justice’s top job the week before, did not reply until the next morning. He said only that the FBI was on the case—a not very encouraging response, given the agency’s history of hostility toward the civil rights movement. Indeed, J. Edgar Hoover had informed Attorney General Katzenbach that the Marion riot was “grossly exaggerated,” that there was “no truth to the statements that Negroes have been brutally assaulted.” The White House reaction was equally tepid: the president was being kept abreast of developments, said a spokesman the following day. Apparently, the administration believed Hoover’s report that there had been “no police brutality but only the use of force necessary to handle an unruly mob.” The evening news programs showed no film, and America’s most influential newspapers published no photographs to prove Hoover wrong.52

King’s illness prevented him from returning to Selma until Monday afternoon, February 22. He saw immediately that the Marion incident had increased tensions in the city. Colonel Lingo’s state troopers, fresh from their Thursday night victory, were now present on the streets of Selma, backing up Clark’s posse. Later that night Katzenbach telephoned King with the news that the FBI had learned of a plot to assassinate the reverend during his visit. King asked for the FBI’s protection, but Hoover refused.

Nonetheless, death threats did not stop King from leading two hundred senior citizens to the courthouse the next morning. There they waited patiently in line to sign the appearance book. There were no incidents, but the group noticed many more sullen white men on street corners observing them than had been present at earlier marches. Afterward King briefly visited Jimmie Lee Jackson at Good Samaritan Hospital. “He seems to be in good spirits,” King later told reporters. He also visited Marion that afternoon, where he found the Zion’s Chapel Methodist Church filled to overflowing with the crowd waiting to hear him speak. “There is no price too great to pay for freedom,” he told them. “We have now reached the point of no return. We must let George Wallace know that the violence of state troopers will not stop us.” One possible response was to organize a motorcade from Selma to Montgomery, but King didn’t say much more about it. He left Selma that night for a fund-raising trip to California.53

During the next few days Jackson improved slightly, so hopes rose that he might recover. His legal prospects were grimmer. Following the shooting Colonel Al Lingo formally arrested him, charging him with “assault and battery with intent to murder a peace officer.” On February 23 he was interviewed by FBI agents and allowed photographers to take pictures of his wound, where the bullet had entered his stomach and exited through his left side.

Then Jackson took a turn for the worse. Late on the night of February 25 he had difficulty breathing. Doctors rushed him to surgery, where they opened his stomach to find a massive infection. He slipped into a coma and died at 8:10 the following morning. The official cause of death was listed as “Peritonitis due to gunshot wound of abdomen.” His killer would not be brought to justice until November 2010, when retired trooper James B. Fowler pled guilty to a charge of “misdemeanor manslaughter” in the Jackson shooting and was sentenced to six months in prison. Even then, Fowler insisted that he shot Jackson in self-defense.54

Jim Bevel, recovering from pneumonia, blamed himself for Jackson’s death and the injuries Marion’s demonstrators sustained. After all, Bevel and his wife, Diane Nash, were the ones who for two years had worked on Martin Luther King until they finally persuaded him to go to Selma to campaign for voting rights. So they demanded action. Bevel met with James Orange and other activists and discussed the King motorcade. Lucy Foster, a Marion resident, suggested instead that they march from Selma to Montgomery, and Bevel was immediately taken with the idea. Others were thinking along similar but more brutal lines. Albert Turner was so angry that he “wanted to carry Jimmy’s body to George Wallace and dump it on the steps of the capitol.” That anger had to be diffused, Bevel thought, and a five-day march would help to do so as it would also focus the nation’s attention on Alabama’s politically sanctioned brutality and the cause that had led to Jackson’s murder: the need for a voting rights bill.55

The time was right “to do something dramatic,” Bevel told Bernard Lafayette on February 26 as they drove to Marion to express their condolences to Jackson’s family. Lafayette was shocked at the appearance of the Jackson home. He was used to seeing the impoverished conditions in which most blacks in the South lived, but Jackson’s farm and tiny shack, which housed four people and had neither electricity nor running water, was especially stark and depressing.

Cager Lee and his daughter Viola were bandaged and still in pain, but they were willing to talk about Jimmie Lee and the future of the civil rights movement. “I wish they had taken me instead of the boy,” Lee told them over and over. Bevel asked him if he thought they should march again or end the demonstrations. Lee replied quickly: “Voting is what this is about”—they must continue. Bevel invited Lee to join him at the head of the march, and the old man agreed. “I’ll walk with you,” he said. “I’ve got nothing to lose now, . . . they’ve taken all I have. We’ve got to keep going now.” Leaving the Jackson family to their grief, Bevel burst into tears.56

That night, at a mass meeting in Selma’s Brown Chapel, Bevel talked about Jackson’s death and how the community should respond. “I tell you, the death of that man is pushing me kind of hard,” he told his audience of more than six hundred people. “The blood of Jackson will be on our hands if we don’t march.” They must take their message directly to George Wallace in the Alabama capital, he said. “Be prepared to walk to Montgomery. Be prepared to sleep on the highways,” Bevel urged the crowd, and the people cheered.57

Bevel had committed King’s organization to an action his boss had not yet approved, but his actions had left King little choice. Caught between the agony of his supporters—who needed desperately to respond to Jackson’s death—and his awareness of the dangers that he and his fellow activists would face, they went forward with their plans, and King reluctantly chose to march. Privately, however, he looked for ways to limit his participation in an honorable way.

On March 3 King spoke at Jackson’s funeral at Zion’s Chapel Methodist Church, telling the crowd of four hundred that “Jimmie Lee . . . is speaking to us from the casket and he is saying to us that we must substitute courage for caution. . . . We must not be bitter, and we must not harbor ideas of retaliating with violence. We must not lose faith in our white brothers.” As he led a crowd that now numbered one thousand to the gravesite, he again expressed worry about his own future, as death threats multiplied. To the Reverend Joseph Lowery, an SCLC board member, he said, “Come on . . . this may be my last walk.” Later that day Bevel, with King’s approval, announced that King would lead a march from Selma to Montgomery, a fifty-four-mile trek, on Sunday, March 7.58

News of the march created consternation on both sides of the struggle. SNCC saw it as another publicity stunt, a staged theatrical event that starred King at the expense of local leaders who had long struggled in the shadows. While they rode the Freedom Rider buses and were beaten in Birmingham and Montgomery and risked their lives in Mississippi during Freedom Summer, King—who they derisively called “de Lawd”—remained above the battle, hiding in the pulpit. Nonviolence didn’t help the victims of Marion, SNCC activists pointed out. Their leaders met twice in long and bitter meetings, finally deciding to give the march only “token support.” Individual members could participate if they wished. John Lewis, who helped found SNCC and was a battle-scarred veteran, broke with his friends and associates. “If these people want to march,” he said, “I’m going to march with them.”59

In Montgomery, Governor Wallace and his advisers sought a way to handle this crisis. Bill Jones, an influential aide to the governor, surprised everyone by recommending that they do nothing. He felt that King’s forces expected to be arrested and were not seriously planning for such a long and difficult trek. Informants planted inside the movement revealed that the marchers thought Selma’s jail was their likely destination, not the state capitol. Just ignoring the marchers would, Jones hoped, “make them the laughingstock of the nation and win for us a propaganda battle.” At first Wallace accepted this strategy. However, he changed his mind when he encountered opposition from state legislators, especially those from Lowndes, the most dangerous county in south-central Alabama and the area through which the marchers would pass. “I’m not going to have a bunch of niggers walking along a highway in this state as long as I am Governor,” he proclaimed. Later he announced that nobody would be allowed to march and that Colonel Al Lingo was instructed to “take whatever steps necessary” to stop it.60

King met again with the president on the evening of March 5. And again there was good news and bad. The president now seemed committed to a voting rights law, not a constitutional amendment, and he urged King to meet with Katzenbach to work out the details. But he provided no specific information about the substance of the bill and promised nothing. Then suddenly Johnson switched course: his top priority for the moment was his education bill, and he asked King to contact legislators to push for its passage. It was lack of education that hurt blacks most, Johnson claimed, stating, “Now, by God, they can’t work in a filling station and put water in a radiator unless they can read and write. . . . Now that’s what you damn fellows better be working on.” The two spent little time discussing the coming march on Selma, now just two days away. A disappointed King returned to Atlanta.61

The march from Selma to Montgomery would be a historical event that President Johnson would later compare to Lexington and Concord, as it would transfix the nation and help smooth the passage of the Voting Rights Act. But this momentous episode in the history of the civil rights movement began as a comedy of errors. Learning of Wallace’s plans to stop the marchers and fearful of violence and the possibility of his own assassination, King met with his top aides on the night of March 6. Perhaps it might be wise to postpone the march, he told them, although he had not decided what to do. Everyone except Jim Bevel and Hosea Williams agreed that a postponement might be the best course.62

Early the next morning King made up his mind. Hurriedly he called Andy Young and asked him to go immediately to Selma to cancel the march. Young took an 8 a.m. flight to Montgomery, rented a car, and raced to Selma. When he drove over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which the marchers would have to cross when leaving downtown Selma on their way to Montgomery, he saw an ominous site: hundreds of state troopers, city police, and Clark’s posse already in place atop their horses. At Brown Chapel he received another shock: six hundred would-be marchers—men, women, teenagers, and even children—all preparing for the journey ahead. Among them were heartbroken but determined people from Perry County who wanted to honor Jimmie Lee Jackson.

Young cornered Williams, asking why he had not followed King’s order to postpone the march. Williams claimed that King had “reauthorized the march.” Find Bevel, Williams said, he had talked recently to King and would back up Williams’s story. Bevel did, stating that King had changed his mind and had said that the march should go forward. Young must have felt like a character in Through the Looking-Glass.

The only way to resolve the conflicting information was to ask King himself, a difficult task, as King was preaching at his father’s church in Atlanta. With Ralph Abernathy’s help, Young and the march’s organizers were able to confer with King. By this time Young was in favor of the march going forward. “All these people are here ready to go now,” Young told King. “The press is gathering expecting us to go, and we think we’ve just got to march, even if you aren’t here. There’ll probably be arrests when we hit the bridge.”

King reluctantly gave his assent. But he did issue one command: two of his top assistants should stay behind to be ready for any unexpected emergencies. Because Lewis was technically a SNCC man, Williams, Bevel, and Young flipped a coin to see who would join him. Williams won.63

And so at 2:18 p.m., after a prayer led by Andy Young, the singing of “God Will Take Care of You,” and a command from Wilson Baker that the marchers re-form themselves into proper parade order, the six hundred set out, with Williams and Lewis in the lead. Lewis didn’t know what the day would bring. Nobody was really ready for a five-day, fifty-mile hike. He was “playing it by ear.” In his backpack were an apple, an orange, a toothbrush, toothpaste, and something to read—everything he needed to pass the time in one of Selma’s rancid jail cells.

Rev. Andrew Young leads a prayer before the marchers set out for the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7, 1965. Kneeling, to Young’s right, are Hosea Williams and John Lewis (tan raincoat); to Young’s left are Albert Turner and Amelia Boynton. © 1965 SPIDER MARTIN

A few days before, King had said, “We will write the voting rights law in the streets of Selma.” He was wrong. The Voting Rights Act would be written—in blood—on the Edmund Pettus Bridge.64