CHAPTER SEVEN

THE DAY IN NEW YORK

It was when curiosity about Gatsby was at its highest that the lights in his house failed to go on one Saturday night—and, as obscurely as it had begun, his career as Trimalchio was over.

The Great Gatsby, Chapter 7

Meaning can be salvaged from the wreckage of experience: accidents may reveal a pattern, a composition of sorts, if we look closely enough. It is only since the advent of cars that one meaning of the word “accident” has pushed itself to the front of the conversation so violently; accident has not lost its ability to mean chance, of course, although it tends now to mean mischance. But because the accidental also means the contingent, Catholic theologians used the word “accidental” to describe the inessential bread and wine left behind after the ritual of communion had turned them into mystical symbols. At story’s end, Gatsby finds himself left only with accidentals, the inessential objects that once had glittered for him, disenchanted things made ordinary again. The accidental is the merely material, once its mystical promises have been abandoned. It is no accident that Fitzgerald uses an accident—and the word “accident,” repeatedly—to bring about this turn in a carefully composed final three chapters about accidents and disenchantment, for the accidental is all that we are left with once we have lost our illusions.

The December 1922 entry in Fitzgerald’s ledger reads: “A series of parties—the Boyds, Mary Blair, Chas & Kaly. Charlie Towne.” It is likely another of his retrospective entries, a hazy sense of parties blending one into another. His memory of that December stretched out into a steady silvered roar, a catalog of parties as a list of names. After a while no one even knew whose party it was. The revels went on for weeks: people came and went, but the party survived. If you surrendered to the need for sleep, you returned to find that others had sacrificed themselves on the altar of keeping it alive, Zelda wrote later. She took a picture of their Great Neck house in the snow and decorated it with spring flowers.

Scott and Zelda drew up a list of “Rules For Guests At the Fitzgerald House”:

1. Visitors may park their cars and children in the garage.

2. Visitors are requested not to break down doors in search of liquor, even when authorized to do so by their host and hostess.

3. Week-end guests are respectfully notified that the invitations to stay over Monday, issued by the host and hostess during the small hours of Sunday morning, must not be taken seriously.

Once the guests had arrived the rules of the Fitzgerald house were invoked. Everyone slept till noon—including the baby, whom, it was said, they used to slip some gin so she would sleep through the racket. Guests would pass out in the hammock in the backyard, or on the sofas and the floors; others wrote of hiding in the cellar to get away from the noise. More than once their houseman found both Fitzgeralds asleep on the front lawn when he awoke in the morning: by the time they left Long Island, Scott was said to have slept on every lawn from Great Neck to Port Washington. Zelda told an interviewer in 1923 that their meals at Gateway Drive were “extremely moveable feasts,” which sometimes seemed to mean moving away from the idea of providing food at all.

“The remarkable thing about the Fitzgeralds,” Bunny Wilson later explained, “was their capacity for carrying things off and carrying people away by their spontaneity, charm and good looks. They had a genius for imaginative improvisations.” Like Gatsby’s ostentatious parties, the Fitzgeralds’ parties were theatrical and spectacular—and it’s no good being theatrical without an audience. A decade later Scott reminded Zelda that they had been “the most envied couple” in America in the early 1920s. She replied, “I guess so. We were awfully good showmen.” For Gatsby, the cost of being a showman is that audiences are indistinguishable from witnesses; he must end his career as Trimalchio when he needs to protect the secret of his affair with Daisy, to keep the servants from gossiping. As for the Fitzgeralds, Scott later wrote, “we had retained an almost theatrical innocence by preferring the role of the observed to the observer.” Gatsby’s ostentation is similarly innocent, although he prefers to observe its effects from the margins.

Zelda so enjoyed being observed that she continued to punctuate their parties with “exhibitionism,” to use the new psychoanalytic term. George Jean Nathan wrote in his memoirs years later of instances of Zelda “divesting herself” of her clothes, once in the middle of Grand Central Station, he claimed, and another time standing on the railroad tracks in Birmingham, Alabama. According to Nathan, Scott told him that Zelda stood naked on the tracks, waving a lantern and bringing the train to a halt; “Scott loved to recount the episode in a tone of rapturous admiration.” Nathan sounded testy when he wrote this account, but in the golden years he had written Zelda several notes in flirtatious admiration: “Nothing about you ever fades,” he told her in April 1922, after seeing her in New York that March.

Nathan also claimed that during the planning of Gatsby Fitzgerald asked for his help in meeting various bootleggers upon whom he could model his “fabulously rich Prohibition operator who lived luxuriously on Long Island.” And so, Nathan recalled, “I accordingly took him to a house party on Long Island at which were gathered some of the more notorious speakeasy operators and their decorative girl friends.” One might have thought that Fitzgerald didn’t require Nathan’s assistance in meeting bootleggers and their clients on Long Island, but perhaps Nathan had his own underground pipeline. Or perhaps his memory was deceiving him.

Others were convinced that Fitzgerald’s fondness for bourgeois revels was symptomatic of a more fundamental philistinism. Edmund Wilson’s 1923 essay “The Delegate from Great Neck” imagines Scott as a fledgling Rockefeller enthusiastically preaching the gospel of wealth:

Can’t you imagine a man like [E. H.] Harriman or [James J.] Hill feeling a certain creative ecstasy as he piled up all that power? Think of being able to buy anything you wanted—houses, railroads, enormous industries!—dinners, automobiles, stunning clothes for your wife—clothes like nobody else in the world could wear!—all the finest paintings in Europe, all the books that had ever been written, in the most magnificent editions! Think of being able to give a stupendous house party that would go on for days and days, with everything that anybody could want to drink and a medical staff in attendance and the biggest jazz orchestras in the city alternating night and day! I must confess that I get a big kick out of all the glittering expensive things.

Wilson can’t have been paying attention to such stories as “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” in which Fitzgerald had already shown his contempt for tycoons who clutched at glittering expensive things—even if he admired the glittering things themselves.

Wilson uses (an equally ventriloquized) Van Wyck Brooks in the essay to voice an older, more puritanical tradition in American letters; Wilson’s Brooks fears that Fitzgerald and his generation are permitting “art to become a business,” surrendering to “the competitive anarchy of American commercial enterprise,” which would create only “money and hollow popular reputations,” bringing “nothing but disillusion and despair.”

The fictional Fitz ends the dialog by urging Brooks to come to a Great Neck party:

Maybe it would bore you to death—but we’re having some people down who ought to be pretty amusing. Gloria Swanson’s coming. And Sherwood Anderson and Dos Passos. And Marc Connelly and Dorothy Parker. And Rube Goldberg. And Ring Lardner will be there. You probably think some of those people are pretty lowbrow, but Ring Lardner, for instance, is really a very interesting fellow: he’s really not just a popular writer: he’s pretty morose about things. I’d like to have you meet him. There are going to be some dumb-bell friends of mine from the West but I don’t believe you’d mind them—they’re really darn nice. And then there’s a man who sings a song called, Who’ll Bite your Neck When my Teeth are Gone? Neither my wife nor I knows his name—but his song is one of the funniest things we’ve ever heard!

Wilson’s portrait is deeply patronizing, his Fitzgerald little more than a buffoon, but it also suggests the cheerful exuberance with which his friend greeted the lunatic energy of the world around him. Wilson did not understand until much later—until it was, in a sense, too late—that another part of Fitzgerald was always standing aside, holding tight to a devout faith in art and viewing their debauchery with hard, cold eyes. Fitzgerald could see that materialism led to disillusion and despair, and debased ideals, as clearly as Wilson or Brooks. When he conceived of his fourth novelistic alter ego, Dick Diver in Tender Is the Night, Fitzgerald called him a “natural idealist, a spoiled priest”—not an indulged priest but a corrupted one, ruined by the glittering expensive things, the heat and the sweat and the life of the carnival he is running.

As it happens, Van Wyck Brooks offered his own memory of the Fitzgeralds, far less censorious than Wilson’s imaginary debate. Brooks wrote of a dinner party at Ernest Boyd’s apartment on East Nineteenth Street, to which both Fitzgeralds arrived an hour late, after everyone had finished eating. Sitting at the dinner table, they “fell asleep over the soup that was brought in, for they had spent the two previous nights at parties. So Scott Fitzgerald said as he awoke for a moment, while someone gathered Zelda up, with her bright cropped hair and diaphanous gown, and dropped her on a bed in a room near by. There she lay curled and asleep like a silky kitten. Scott slumbered in the living-room, waking up suddenly again to telephone an order for two cases of champagne, together with a fleet of taxis to take us to a night-club.”

At least one contemporary could see that Fitzgerald’s gift for pleasure was not incommensurate with his gift for art. In 1924 Ernest Boyd wrote a book called Portraits, which included a depiction of Scott and Zelda. Fitzgerald told John Bishop that he rather liked Boyd’s portrait of “what I might ironically call our ‘private’ life.” Scott Fitzgerald was “a character out of his own fiction, and his life a series of chapters out of his own novels,” Boyd declared. “Zelda Fitzgerald is the blonde flapper and her husband the blonde philosopher of the Jazz Age.” Here was a man who “combines the most intellectual discussion with all the superficial appearances of the wildest conviviality . . . He is intensely preoccupied with the eternal verities and the insoluble problems of this world. To discuss them while waiting for supper with Miss Gilda Gray is his privilege and his weakness.” Boyd may have seen Fitzgerald’s love of glamor as a weakness, but it did not tempt him into underestimating the shrewdness of his views: Fitzgerald “is one of the few frivolous people with whom one can be sure of having a serious conversation.” (In fact, history would prove, Fitzgerald was one of the few serious people who was capable of so much frivolity.) In particular, “upon the theme of marital fidelity his eloquence has moved me to tears,” said Boyd, “and his stern condemnation of the mores of bohemia would almost persuade a radical to become monogamous. There are still venial and mortal sins in his calendar.”

Fitzgerald’s natural milieu was on Broadway, in the “Roaring Forties” or in Harlem cabarets, Boyd continued; a typical night consisted of “music by George Gershwin, under the baton and rhythmically swinging foot of Paul Whiteman; wines and spirits by special arrangement with the Revenue Department,” followed by a wild drive back to Long Island in their secondhand red Rolls-Royce, “the most autonomous automobile in New York.” After a night during which they wandered from cabarets like the Palais Royal to the Plantation Club, from the Rendezvous to Club Gallant, with many a detour en route, finally would commence a miraculous departure for Great Neck. Scott would pull out his checkbook “for the writing of inexplicable autographs in the tragic moments immediately preceding his flight through the weary wastes of Long Island,” and a madcap drive home would ensue. “By an apparently magic, and certainly unexpected, turn of the hand,” the car would suddenly swing round, “dislodging various friends who have been chatting confidently to the occupants,” while standing on the running boards. After summarily dispensing with extra passengers, Scott would begin the erratic journey back to Long Island. “When it is a moral certainty that one is miles off the true course,” Fitz would suddenly turn over the wheel to some passenger who had never driven a car before and climb into the back to join the sleeping party, confident that they’d be carried home. Eventually, after “consulting” with various policemen who were willing to overlook the Volstead Act when presented with evidence of a fiduciary trust, the car would glide graciously to their front door in Great Neck.

Boyd ended his portrait of the Fitzgeralds by noting that after rising at midday, and finding some party to while away the afternoon, “the evening mood gradually envelops Scott Fitzgerald.” Another “party must be arranged. By the time dinner is over, the nostalgia of town is upon us once more. Zelda will drive the car.”

Glowing lights scintillate and vanish into the darkness. We are trying to find what Henry James called “the visitable past,” to revisit Babylon—but it isn’t easy to discern the route to the lost city.

Charlotte Mills announced on Friday, December 1, that she was “disgusted” by the prosecution’s failure to bring anyone to trial for her mother’s murder. A resourceful girl, she had decided to solve the mystery herself—by speaking to her mother’s ghost. She had been inspired by recent press reports of Arthur Conan Doyle’s experiments with séances and his well-publicized insistence that science supported his investigations. “If what I read is true,” Charlotte explained, “I shall certainly be able to communicate with my mother and learn the truth.” Unfortunately for Charlotte, what she read wasn’t true, but she insisted that she would continue to “fight for a real investigation.” A week later Conan Doyle wrote to the New York Times to protest about a large reward recently offered by Scientific American magazine for any proof of the claims made by Spiritualists. Such a reward, Conan Doyle argued, would “stir up every rascal in the country,” inciting fakers, frauds, and publicity seekers.

That Sunday, a New Jersey minister preached about the Hall–Mills “fiasco,” inveighing against the widely held opinion that local citizens had “put the question of expense ahead that of justice and the protection of society.” “There is a trend,” the minister observed, “toward a luxurious and vicious form of life, exceedingly wicked and corrupt, and the use of violent power to obtain advancement. This constitutes our modern Babylon and it will assuredly be destroyed as was the Babylon of old, not leaving a vestige of its greatness behind.” Their Babylon would disappear, it is true—but another would rise in its stead.

If revisiting Babylon is difficult, even visiting Babylon was a dangerous enterprise. On Tuesday, December 5, 1922, the Tribune reported with palpable amusement that a monkey had been killed in the town of Babylon, Long Island, for “hugging the postmaster’s wife”: a small monkey, which might have been the “bootlegger’s baboon” that had escaped and terrorized Babylon a few weeks earlier (“though those who saw the latter animal emphatically deny it”), was shot when it leaped into the open horse-drawn surrey of Mrs. Samuel Powell. She was on her way to buy a goat when the monkey “dropped right into Mrs. Powell’s lap and embraced her fervently.” Her passenger, Henry Kingsman, was an expert on goats, the reporter noted, but knew nothing about monkeys; however, as Mrs. Powell screamed at Kingsman to help her he “obediently detached the monkey and flung it to the road.” A hunter emerged from the side of the road, as if in a modern fairy tale. The hunter’s “specialty” was neither goats nor monkeys, but rabbits; however, “being a somewhat less ethical savant than Mr. Kingsman,” the hunter aimed his gun and “blazed away” at the monkey. “The charge struck the monkey, and the monkey bit the dust.” The hunter refused to give his name to Mrs. Powell, but he “presented the defunct monkey to her,” which it seems she kept as a souvenir. Mrs. Powell drove home “with a dead monkey and a live goat and an anecdote that will brighten the winter for Babylon.” The World was also amused enough to share the story, hinting that the monkey might have been a victim of the unwritten law: “A monkey was shot near Babylon, L.I. for hugging a married woman. Monkey business of this kind is always dangerous,” as the murders of Hall and Mills had shown.

Murder mysteries creep into Chapter Seven almost immediately. When Nick and Gatsby arrive together for lunch at the Buchanans’ on the last day of the summer, Nick imagines that the butler roars at them from the pages of a detective novel: “The master’s body! . . . I’m sorry Madame but we can’t furnish it—it’s far too hot to touch this noon!”

On this climactic day Daisy inadvertently reveals that she is in love with Gatsby by telling him how cool he always looks—Tom suddenly hears an inflection in her “indiscreet voice,” that voice full of money, and realizes that she and Gatsby have been having an affair. The realization sets the plot into motion and all five main characters drive into New York. Tom insists on driving Gatsby’s yellow “circus wagon” of a car and Gatsby grows angry, his anger as revealing as Tom’s. Nick observes a look on Gatsby’s face that he declines at first to characterize, but that he sees two more times before the episode is finished: “an indefinable expression, at once definitely unfamiliar and vaguely recognizable, as if I had only heard it described in words.” Near the chapter’s end Nick will finally tell us what it was: Gatsby looks like a killer.

Meanwhile Tom says repeatedly that he’s been making an “investigation” into Gatsby’s affairs. Insisting that he’s not as dumb as they think, he claims to have a kind of “second sight” and begins to say that science has confirmed such phenomena, before realizing that he can’t explain how. Abruptly abandoning another of his pseudoscientific theories (when “the immediate contingency overtook him, pulled him back from the edge of the theoretical abyss”), Tom settles for repeating that he’s been making an investigation, and Jordan jokes: “Do you mean you’ve been to see a medium?” The jest merely confuses Tom, while Jordan and Nick laugh at the idea of Tom as a Conan Doyle using séances to solve the mystery of Gatsby’s identity.

They stop for gas at the garage among the ash heaps, as gray, ineffectual Wilson emerges from the dark shadows of the story’s margin. He looks sick, telling them as he gazes “hollow-eyed” at the yellow car that he “just got wised up to something funny the last two days” and wants to go west, the place of fresh starts and frontiers, along with his wife.

As Nick looks up and sees the giant eyes of T. J. Eckleburg keeping their composed vigil, he also notices another set of eyes, discomposed, peering out at their car from an upstairs window above Wilson’s garage. It is Myrtle, and she too has “a curiously familiar” expression on her face (her symmetry with Gatsby subtly recurring), an expression that seems “purposeless and inexplicable” until Nick realizes that “her eyes, wide with jealous terror, were fixed not on Tom but on Jordan Baker, whom she took to be his wife,” as they drive off in their expensive car to New York. Scholars have asked why Nick finds this expression “curiously familiar,” and speculated that perhaps he recognizes it from the movies. But expressions are also phrases, and a woman with jealous terror in her eyes would be a curiously familiar expression to anyone who had been following the Hall–Mills case, as well.

When the party from Long Island arrives at the Plaza, Tom forces a confrontation over the affair by calling Gatsby’s relationship with Daisy a “presumptuous little flirtation.” The Trimalchio drafts are rather more explicit, as they often are: Nick says he and Jordan wanted to leave, for “human sympathy has its curious limits and we were repelled by their self absorption, appalled by their conflicting desires. But we were called back by a look in Daisy’s eyes which seemed to say: ‘You have a certain responsibility for all this too.’” Nick’s responsibility remains, but his acknowledgment disappears in the final version, an implication of his culpability to which he never admits.

It is as Gatsby grows more betrayed by Daisy’s admission that she loves him “too,” instead of with the singular devotion he has brought to her, that Nick realizes Gatsby “looked—and this is said in all contempt for the babbled slander of his garden—as if he had ‘killed a man.’ For a moment the set of his face could be described in just that fantastic way.” How murderous is Gatsby? Fitzgerald will not tell us, preferring to “preserve the sense of mystery” as he later wrote in a letter, but he carefully makes the insinuation, even if it’s a conditional one.

Daisy and Gatsby leave in Gatsby’s car to return to Long Island, while Tom, Jordan, and Nick drive the blue coupé back across the ash heaps. Nick suddenly remembers it is his thirtieth birthday and begins to reflect on aging as they drive “on toward death through the cooling twilight.” By placing this remark just after Nick’s meditation on mortality, Fitzgerald cushions its barb. We may be lulled on first reading into thinking that they drive toward death in the general human sense, as if Tom’s wheeled chariot hurries them toward it. But there are more imminent, and more violent, deaths waiting. When Daisy and Gatsby leave the hotel, Fitzgerald hints at what will come: “They were gone, without a word, snapped out, made accidental, isolated like ghosts even from our pity.” People can become accidental, too, material accessories—in this case, to murder.

During the first week of December 1922 a swindler named Charles Ponzi was making headlines across America. The “get-rich-quick financier” and Boston-based “exchange wizard” who’d promised his victims 50 percent profit in forty-five days had two years earlier given his name to a particular form of financial fraud: a Ponzi scheme. Ponzi was indicted for one of the biggest swindles in American history, broken by the investigative journalism of the New York Post. Ponzi had been in jail since 1920; by early 1922, financial swindlers across the country were labeled a “Chicago ‘Ponzi’” or an “East Side ‘Ponzi’” as other “Ponzi schemes” quickly followed in the press, and the nation exploded in protest at his willingness to help so many Americans try to get something for nothing. When the Ponzi story first broke in 1920, the New York Times ran an editorial on “The Ponzi Lesson,” a lesson America would spend the rest of the century forgetting.

While serving time, Ponzi continued to be arraigned for other aspects of his mail-order fraud: Massachusetts brought charges of larceny in 1922, putting Ponzi back in the news. When the latest trial began that autumn, the judge warned the jury “against being swayed by popular clamor in reaching a verdict.” The public was still enraged and baying for more of the swindler’s blood.

Ponzi declared during his trial that he hadn’t kept a cent of his spoils, insisting that he had always believed his business was legitimate, thanks to the simple expedient of not enquiring into the law. “I didn’t go into the ethics of the question,” he said. “I decided to borrow from the public and let the public share the profit I made . . . I got my first returns in February [1920] and from that time it grew and grew as people got their returns. Each one brought ten others.” In the early months of 1920 Ponzi began by taking in two thousand dollars a day; by the end of the first month he was making two hundred thousand dollars a day—at least two million in today’s money. On December 2, 1922, headlines across the country reported that Ponzi had been found not guilty of the additional charges and sent back to jail. Eventually he would be deported to Italy.

The big stories of the early 1920s were unforgettable, Burton Rascoe later wrote, for anyone who read the daily newspapers, whether the hysteria over Valentino’s funeral or “the Snyder–Gray and Hall–Mills murder cases.” Although early popular histories of the 1920s all relied upon “the headlines of the more sensational stories in the press,” this didn’t mean that everyone actively participated in the scandals and fads of the era. But they all knew about them. “I did not sit on a flagpole, participate in a marathon dance . . . try to get 1,000 percent on an investment with the swindler Ponzi, nor did I know of anybody, personally, who did.” But everyone followed the scandals: everyone participated in them vicariously, and they were all busily speculating. The twenties were marked by speculation, Rascoe recalled, not just in finance, but as a way of life: “the world seemed to have gone mad in a hectic frenzy of speculation and wild extravagance and I was interested in the phenomenon, especially since nearly all the other values of life had been engulfed by it. To retreat from it was to retreat from life itself.”

Ponzi was only the latest in a long line of American speculators, one article about him suggested. The rush to believe in Ponzi’s promises of vast, easy wealth was no different from the California Gold Rush—or indeed from the discovery of America itself: “get-rich-quick promises” had always lured “venturesome souls . . . from the days of Columbus, who sought a shorter route to the fabled wealth of the Indies, down to the days of Ponzi.”

On Monday, December 11, 1922, Fitzgerald’s agent, Harold Ober, received a story from Scott entitled “Recklessness.” It was never published and, rather fittingly, may have been lost, but we can’t be certain. It is possible that it changed its name to something more aristocratic.

The day before, the film version of The Beautiful and Damned opened in New York at the Strand Theater, a premiere that Scott and Zelda seem to have attended. Fitzgerald would have been in his dinner coat, perhaps recollecting his objection to Scribners’ illustration for the dust jacket of The Beautiful and Damned, which he had disliked. He told Perkins, “The girl is excellent of course—it looks somewhat like Zelda. But the man, I suspect, is a sort of debauched edition of me.” It was a close enough copy to be recognizable, and a distorted enough copy to be distasteful. Fitzgerald complained that the illustrator had drawn the picture “quite contrary to a detailed description of the hero in the book,” for Anthony Patch was tall, and dark-haired, whereas “this bartender on the cover is light haired . . . He looks like a sawed-off young tough in his first dinner-coat.” Not unlike Jay Gatsby then, whom Jordan calls “a regular tough underneath it all.”

The “movieized” version of The Beautiful and Damned, as the papers described it, had received much advance publicity. Fitzgerald clipped out a newspaper advertisement for the film (“Beginning Sunday”), as well as all the New York reviews—the Tribune, the World, the Times, and the New York Review—and saved them in his scrapbook.

The Evening World recommended the “screenic version”—for its superficiality: “We thoroughly believe that if you liked the book you will like the screen edition of this best seller because it does not delve quite so deep into flappers as one might suspect.” When the World reviewed the film in early 1923 it suggested that art was copying life: “Quite a lot of the frenzy that is poured out of the silver cocktail shaker gets into this picture at the Strand. We have a suspicion that a good camera man could slip into the living room of a great many young homes around New York almost any Saturday night and grind out reproductions of several of its scenes from real life.” The novel “merely presented a little bit of life as it is being lived by the sweet and carefree.” While “not a profound picture play (if there is such a thing),” the review added, the film was “interesting by virtue of its success in clinging closely to reality.”

Like so much else, the film has been lost, but another review Fitzgerald saved in his scrapbook gives a startling glimpse of the ending. At the conclusion of the novel, Anthony and Gloria Patch inherit a fortune, which is the final push over the edge into dissipation and damnation; they have been ruining themselves for some time, and Fitzgerald makes it clear that riches will complete their degradation. In the film, by contrast, the Patches were evidently redeemed by wealth. Their “sudden wealth takes on a religious aspect,” wrote Life. “It serves to purge the hero and heroine of their manifold sins and wickednesses, and in the final subtitle, Anthony says, ‘Gloria, darling, from now I shall try to be worthy of our fortune and of you.’” They should have changed the film’s title to The Beautiful and Blessed, a sentiment more consonant with the simple credo that God must love rich people more.

Fitzgerald was not impressed. A day or two after seeing the film, he wrote the Kalmans: “it’s by far the worst movie I’ve ever seen in my life—cheap, vulgar, ill-constructed and shoddy. We were utterly ashamed of it.” He added buoyantly, and somewhat inconsistently, “Tales of the Jazz Age has sold beautifully,” closing the letter with a signature boxed in by a dotted line, so that it could be cut out as an autograph. It was a gag Fitzgerald enjoyed. He had sent a similar autograph to Burton Rascoe earlier in the year with the suggestion, “clip for preservation on dotted line”:

Fitzgerald would doubtless have been relieved to learn that the film of The Beautiful and Damned was lost: he clearly thought it less worth preserving than his signature. But he would have been delighted to know that he is the reason we feel its loss.

The winter’s first serious snowstorm fell on Thursday, December 14, leaving three inches of crisp white snow all over the city and causing a sharp increase in traffic accidents. Careless drivers were not helped by the icy rain that followed in its wake. “That winter to me is a memory of endless telephone calls and of slipping and sliding over the snow between low white fences of Long Island, which means that we were running around a lot,” Zelda wrote in a story later.

The Times reported that on the same Thursday in December President Harding had told the Senate, “When people fail in the national viewpoint and live in the confines of a community of selfishness and narrowness, the sun of this Republic will have passed its meridian, and our larger aspirations will shrivel in the approaching twilight.” It is possibly the only wise statement Harding made during his presidency—until he supposedly confessed just before he died under the pressure of the corruption scandals that engulfed his administration in the summer of 1923, “I am not fit for this office and never should have been here.”

A new America was pushing its way up through the approaching twilight, mushrooming into life. In November, a New York woman had sued her daughter for injuries sustained in a car crash, testifying that “her daughter was driving fast, and just before the accident she had cautioned her to drive more slowly.” The aptly named Mrs. Gear was seeking fifty thousand dollars from her daughter as the price of ignoring a backseat driver. A week later, a woman in Missouri successfully sued a railroad company for causing her to gain 215 pounds after, she claimed, an accident made her endocrine glands cease to function; she sought fifty thousand dollars and was awarded one thousand in damages. “Gains Weight, Gets Damages,” jeered the Times. “Missouri Woman Declared Railway Accident Trebled Her Avoirdupois.”

Two years earlier, an article in the Times feared that it saw “American Civilization on the Brink,” lamenting: “As I watch the American Nation speeding gayly, with invincible optimism, down the road to destruction, I seem to be contemplating the greatest tragedy in the history of mankind.”

While the temperature in New York continued to drop and winter settled in, the Tribune offered some thoughts on “Murder and the Quiet Life.” Conclusions were beginning to be drawn—not about who had murdered Edward Hall and Eleanor Mills, but about the “historic collisions” that produce the best stories. Recent public interest in the New Brunswick murder case had crossed class boundaries and made writers of everyone. No one was immune from guesswork, and the entire nation was absorbed in the case, speculating over the dinner table about who had committed the crimes. “Everybody followed it. Persons of the palest, most rarefied refinement watched the divagations of the authorities and made shrewd guesses. The mystery maintained itself on the front pages for a length of time probably unparalleled, under similar circumstances, in the annals of newspaperdom . . . A good mystery is, after all, a good mystery; which is to say that it embraces surprise, suspense, illusion; yea, reader, all the constituents of pure romance.”

The investigation into the New Brunswick murders was slowing down, but the nation was unwilling to relinquish the story. Without an official version, readers were writing their own endings. Thousands of people, “shielded by the cloak of anonymity,” had offered their theories and opinions about the case: “probably never before in all the history of crime have so many letters been written.” Charlotte Mills decided to share them with the press.

One of her letters came from the ubiquitous John Sumner, of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, asking for information about “certain books” her mother had read. Charlotte wouldn’t tell reporters what her response had been, but shared Sumner’s reply: “I note what you say with reference to your mother having made quite a few criticisms on both books. These criticisms would be of interest if available. I am glad that you feel that such books never influenced your mother in any way. That is the way you should feel in the matter and indicates a degree of faith in the wisdom of your mother which would be fortunate if all young girls could feel.” Reserving judgment may be a matter of infinite hope, but Charlotte had some reason to have lost faith in the wisdom of her mother.

James Mills received a letter on the stationery of a “leading” country club, demanding: “Who said this country is a democracy? That’s a lie! A country where money controls everything, even justice, the most sacred of human institutions, cannot be a true democracy! Isn’t there anybody who has nerve enough and backbone enough to take a hand in this? . . . What about fingerprints? What a comedy throughout!” And a woman wrote to Charlotte: “Imagine that doctor not reporting that your mother’s throat was cut. My husband is a young conscientious doctor, and he says it is a crime the way some doctors are influenced.”

Under pressure, New Brunswick officials insisted that they were doing more “than the public suspect.” Officers Lamb and Dickman had been replaced by New Jersey state police, who were “conducting an investigation into New Brunswick’s underworld.” New evidence had suggested they should “delve into New Brunswick’s lower social strata in their search for the murderer.”

Almost everyone had theories, Zelda later observed: that the Longacre Pharmacies carried the best gin in town; that anchovies sobered you up; that you could tell wood alcohol by the smell; that you would be drunk as the cosmos at the end of the night and discover that there were others besides the desk sergeant in the Central Park Police Station. Unfortunately, she added, none of her theories worked.

As Daisy and Gatsby drive home in the cooling twilight, Myrtle Wilson rushes out into the street and is struck down by the car that symbolizes Gatsby’s wealth. Her thick, dark blood pools into the ashes and dust of the road; her breast is torn open and her mouth ripped, as if she died choking on her own vitality. She expires under the faded eyes of T. J. Eckleburg, the billboard her husband mistakes for God.

Nick is able to reconstruct what happened from the testimony in the newspapers, legitimating Fitzgerald’s sudden shifts in perspective to what George Wilson’s neighbor Michaelis observed at the ash heaps. Nick is now narrating as a reporter and so can tell us of things that he didn’t see at first hand. The jump to Michaelis’s point of view begins with the news that he was the “principal witness at the inquest,” suggesting that Nick reconstructs this account of George Wilson’s movements from the inquest itself and from the newspapers’ reports.

While Tom, Nick, and Jordan were also driving back through the twilight toward Long Island, Wilson was telling Michaelis of his determination to take his wife west. Michaelis was astonished at Wilson’s sudden vigor: “Generally he was one of these worn-out men: when he wasn’t working he sat on a chair in the doorway . . . when anyone spoke to him he invariably laughed in an agreeable colorless way. He was his wife’s man and not his own.” When Myrtle Wilson breaks out of the room where Wilson has locked her, she taunts him, daring him to stop her (“Throw me down and beat me, you dirty little coward!”), and rushes into the road as a car races toward her in the gloom. It doesn’t stop, even after it’s struck her down; newspapers called it “the death car,” Nick tells us. Michaelis is unsure of its color, but thinks it might have been light green—the fateful inverse of Gatsby’s hopeful green light.

On December 8, 1922, the Evening World reported after a hit-and-run killing in New York that “the police have sent out a general alarm for the driver of the death car.” Given the number of accidents on the roads, newspaper reports of killings involving a “death car” were all too common. It was becoming so familiar that there were jokes about it. Town Topics reported that the new motorcar would come “with springs so perfectly adjusted that the occupants feel no discomfort when the car runs over a pedestrian.” In mid-November the New York police had sought another “death car” after a reckless driver killed an officer; in July, a Mrs. Mildred Thorsen had been killed by a “death car” that continued at high speed after it ran over her. That summer the American papers all reported the sensational story of Clara Phillips, a Los Angeles woman who’d heard that her husband was having an affair with an acquaintance named Alberta Meadows. He was not: rumor had lied again. But Mrs. Phillips believed the rumors and so she’d bashed in Alberta Meadows’s head with a hammer. “‘GOSSIP’ REAL MURDERER OF MRS. MEADOWS” shouted the Evening World. The victim had been found in a pool of blood in her own car; it was promptly labeled “the death car.”

When Tom, Jordan, and Nick return to the Buchanans’ after discovering Myrtle’s body, Nick encounters Gatsby, lurking outside the house. Under the misapprehension that Gatsby was driving the car that killed Myrtle, Nick half expects to see Wolfshiem’s thugs lurking in the shrubbery. But then Nick guesses the truth: the death car was driven by a woman. Daisy is the culprit; devoted Gatsby is watching over her to ensure that Tom doesn’t try “any brutality.” Nick goes back to the house, where he sees Daisy and Tom by the window, talking urgently: “there was an unmistakable air of natural intimacy about the picture and anybody would have said that they were conspiring together.” Nick leaves them to their conspiracy, and Gatsby stays all night at his sacred vigil, still hoping.

On the cold, dry, bright day of Saturday, December 16, the World ran a satirical feature on modern murder, in which a fictional character—who owes a debt to Ring Lardner’s collection of semiliterate rustics and jazzy rude mechanicals—opines on the wide gap between the unrealistic competence of fictional “detecatives” and the incompetence of real ones: “The Government might just so well issue shooting licenses for bootleggers and declare open seasons on rectors in Jersey, because the way it is now, murder ain’t a crime in this country. It’s a sport.” In fact, the character suggested, “if they want to make an arrest in a case like this here New Jersey murder,” they should “arrest the witnesses, the widow, the executors and the owner of the property where the crime was committed upon the ground that he failed to put up a notice reading: ‘Commit No Murders on These Premises. This Means YOU.’”

Having been mined for all it was worth, the rich vein of the Hall–Mills story seemed to be petering out. Mrs. Gibson was still panning for gold, however. She announced that she wanted to make a new statement “supplementing her former story,” but the prosecutor declined to meet her. A private investigator claimed to have found new eyewitnesses, but readers around America scoffed loudly at the idea that yet another person might have witnessed the murders. “If they could just get the fellow who sold the tickets to that affair, they might find out something,” quipped the Cleveland Plain Dealer, a joke that was picked up around the country.

Meanwhile a justice in the New Jersey Supreme Court announced that there was no longer any reason for haste in pursuing the investigation, offering a masterful summation of the facts: “The crime was committed. It did not commit itself. The murderer is still unpunished . . . But in my judgment anything like fervid haste to discover the criminal seems now no longer to exist,” said the Times. (The World quoted him as saying “fevered haste,” which seems more likely; either way, he was in no rush to solve the murders.) “There is nothing mysterious in the fact that the murderer has not been caught,” insisted Justice Parker. “Sometimes they are never discovered and often it has taken years to find them.” He then comfortingly listed a number of recent unsolved murder cases to bolster his argument in defense of the New Jersey justice system.

As 1922 drew to a close, yet another farcical trial was under way, eight miles from Great Neck. That summer, the actress and singer Reine Davies had held a party at her weekend house on Long Island. During the party a prosperous contractor named Wally Hirsch was shot in the face; the force of the blast knocked his false teeth out of his mouth. The teeth were admitted into evidence when the state accused Hirsch’s wife Hazel of attempted murder.

The story had made headlines in June and not only because of its macabre comedy. Celebrity played its role, too, for Reine Davies was the sister of the movie star Marion Davies. Reine Davies had already featured in another trial that January, when she was thrown from her car on Long Island after a collision, and sought half a million dollars in damages from the other driver for head injuries she’d sustained when she almost hit a cow.

A constable was “leading a cow near where the collision happened” and “Miss Davies narrowly missed hitting the cow when she was thrown out.” The constable “dropped the cow’s leash, put on his badge, and charged [Davies’s] chauffeur with driving recklessly.” Davies was awarded $12,500 in damages for her hazardous encounter with nineteenth-century arcadia.

That summer Davies made headlines again for the party she’d thrown in her “rathskellar” (basement bar). Although her famous sister had not attended, their magistrate father had, seeming untroubled by the bibulous atmosphere. As the party was ending guests heard shots. Hirsch was found sitting on a bench outside, drunk and dazed, shot in the face. His wife, running away, began screaming that he made her do it before throwing herself on the ground and drumming her heels hysterically.

Witnesses testified that Hirsch shouted that his wife had shot him, adding that he called her “an offensive name,” which the papers declined to reprint. Davies’s “negro chauffeur,” however, claimed that Hirsch said someone named “Luke McLuke” shot him. When the police arrived, Hirsch told them the same thing, “that Luke McLuke shot him.” They found an automatic and followed a bloody trail from the pistol to the porch, encountering “three sections of false teeth” along the way. Two officers testified that Hirsch told them “Luke McLuke, or something like that, shot him”; “the State then put the teeth in evidence, on the ground [sic] that they had been shot out of Hirsch’s mouth.”

Luke McLuke was the pen name of popular syndicated humorist S. J. Hastings, and “Luke McGlook, the Bush League Bearcat,” also spelled Luke McGluke, was a popular cartoon using the semiliterate baseball humor popularized by Ring Lardner. In 1923 Fitzgerald was interviewed by Picture-Play magazine, and used an imaginary person called “Minnie McGluke” to represent filmmakers’ idea of the average moviegoer: “This ‘Minnie McGluke’ stands for the audience to them who must be pleased and treated by and to pictures which only Minnie McGluke will care for.” To blame Luke McLuke, in other words, was to blame everyone and no one, as if claiming that Hirsch had been shot by John Doe.

When Hirsch and his wife sobered up, both insisted she would never have shot him; perhaps she found him holding a gun and tried to wrestle it from him, but neither could remember what happened. At the trial, witnesses testified that Hirsch had drunk at least twenty whiskeys, snatching cocktails from other guests (who still sounded aggrieved six months later). Everyone was too drunk to remember what happened and Hazel was acquitted.

The World was highly amused, saying that if the story had a “moist beginning,” it had “a very wet ending”: both Hirsches “sobbed together and separately” upon hearing the verdict. Witnesses described Reine Davies’s party in such a way as “to create a thirst even in a hardened Volsteadian”: Davies had “a regular bar, tended faultlessly by a ‘professional bartender’ who dispensed Scotch whiskey, highballs, cocktails and beer while a Negro orchestra added jazz.” The reporter sounded distinctly envious. Even the comparatively staid New York Times called the story a “Highball Epic.”

Reine Davies’s sister Marion lived with William Randolph Hearst—the man who, in four years’ time, would initiate the final phase of the Hall–Mills murder investigation.

American writers including Fitzgerald, Wilson, Rascoe, Boyd, and Bishop had been energetically debating the status of American letters throughout 1922. Van Wyck Brooks wrote, “Our literature seemed to me, in D. H. Lawrence’s phrase, ‘a disarray of falling stars coming to naught.’” In the spring of that year Wilson had observed: “Things are always beginning in America. We are always on the verge of great adventures . . . History seems to lie before us instead of behind.” Americans’ sense of defensive inferiority in regard to European culture was diminishing. Industrial economic might was booming; the arts could not be far behind. “Culture follows money,” Fitzgerald wrote to Wilson in the summer of 1921, during his and Zelda’s first trip to Europe. “You may have spoken in jest about N.Y. as the capitol of culture but in 25 years it will be just as London is now. Culture follows money & all the refinements of aestheticism can’t stave off its change of seat (Christ! what a metaphor). We will be the Romans in the next generation as the English are now.” As usual, Fitz was guessing right. That autumn he wrote, “Your time will come, New York, fifty years, sixty. Apollo’s head is peering crazily, in new colors that our generation will never live to know, over the tip of the next century.”

By the end of 1922, it seemed to many that American culture was consolidating its position. On Christmas Eve, Rascoe reported that a friend recently returned from abroad had found the English “terribly keen about American literature,” “eager to hear all about it, read it and discuss it.” In particular, he’d been surprised to find the English “less snobbish than the Americans.” At home social distinctions ruled, but in England he’d found that just writing “An American” on his card meant he was asked everywhere. He’d been impressed by such democratic egalitarianism, but in Gatsby Fitzgerald suggested another, far more cynical, reason for the warm welcome Americans were receiving in postwar Europe. Scattered among Gatsby’s parties are a number of Englishmen, “all well dressed, all looking a little hungry and all talking in low earnest voices to solid and prosperous Americans. I was sure that they were selling something: bonds or insurance or automobiles. They were, at least, agonizingly aware of the easy money in the vicinity and convinced that it was theirs for a few words in the right key.”

Liking American money was one thing, liking American literature another. After a trip to Britain that summer, Ernest Boyd told Rascoe: “They don’t know whether to begin to regard American literature seriously and they are much upset about it . . . anxious to be reassured that American literature is a joke, so they won’t have to bother about reading it.” And many British writers remained unshakably confident in their inherent right to determine the language: Hugh Walpole read Carl Sandburg’s Chicago poems, and complained: “If this fellow Sandburg will use slang why will he not endeavor to be just a bit more comprehensible. He speaks here, for instance, of an engine’s being ‘switched’ when he might just as easily have used ‘shunted.’ American slang was so incomprehensible that British editions of Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt were being printed with a helpful glossary, including:

Bat—Spree.

Bellhop—page boy.

Bone—dollar.

Darn—puritanical euphemism for the word damn.

Doggone—puritanical euphemism for damn.

Gee—puritanical euphemism for God.

Grafter—taker of bribes.

Guy—fellow.

Heck—familiar for Hecuba, a New England deity.

Highball—tot of whiskey.

Hootch—drink.

Hunch—presentment.

Ice cream soda—ice cream in soda water with fruit flavoring, a ghastly hot weather temperance drink.

Jeans—trousers.

Junk—rubbish.

Kibosh—damper, extinguisher.

Kike—Jew.

Liberal—label of would-be broadminded American.

Lid—hat.

Lounge-lizard—man hanging about in hotel lobbies for dancing and also flirting.

Mucker—an opportunist whose grammar is bad.

To pan—to condemn.

Peach of a—splendid.

Poppycock—rot.

Prof.—Middle-Western for professor.

To root for—to back for support.

Roughneck—antithesis of highbrow.

Roustabout—revolutionary.

Rube—rustic.

Slick—smart.

Spill—declamatory talk.

Tightwad—a miser.

Tinhorn—bluffer, would-be smart fellow.

Tux—Middle-western for Tuxedo, American for dinner jacket.

Weisenheimer—well-informed man of the world.

The errors in translation must have been a source of much amusement to American readers; within a few years, no definitions would be required for jeans, junk, or tux. The American century was at hand, and America was getting ready for a revolution in literature. By 1930 America would see the publication of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms, John Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer, the plays of Eugene O’Neill, the works of Langston Hughes and the other writers of the Harlem Renaissance, and William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, among others.

The endless conversations about the validity of American art necessarily also begged the question of what defined America. Inventing an authentic American literature requires knowing what is authentically American, and American history was similarly accelerating its production. “America is a hustling nation even in accumulating a history,” wrote the New York Times that same Christmas Eve in 1922. “The story of our national life [recently] seemed to be almost pitifully small compared with the ample and anciently rooted histories of European countries. But we have been making up for lost time at a great rate.”

Accelerating the “speed production” of American history also inevitably accelerated debates over the truths of that history. Appalled to find American textbooks teaching a version of American history they considered untrue, veterans of the Great War announced in December that they would seek elimination of “un-American ideals” from schools. One way to pretend to define authentic Americanism is by the simple expedient of labeling other things “un-American.” Thirty years later, America would poison itself in the futile effort to stop “un-American activities.” For now, self-appointed guardians of American culture were urging the revision of American textbooks, to expunge “foreign propaganda,” although no one elaborated upon what this dangerous propaganda actually said. A committee was formed “with a view to eliminating propaganda and to see that the histories teach nothing but American ideals.” Foreign values are propaganda, but American values are ideals. “Want truer history books,” the veterans’ committee insisted. Don’t we all.

For Christmas 1922, Ring Lardner sent a poem to Zelda that reads in part:

Of all the girls for whom I care,

And there are quite a number,

None can compare with Zelda Sayre,

Now wedded to a plumber.

I read the World, I read the Sun,

The Tribune and the Herald,

But of all the papers, there is none

Like Mrs. Scott Fitzgerald.

The poem also made reference to other Great Neck couples, such as the Farmer Foxes, who figure more than once in Scott’s ledger and in the Fitzgeralds’ later correspondence. Zelda wrote Scott ten years later that they had quarreled about everything in Great Neck, including the Foxes, the Golf Club, and Helen Bucks. That reminded her of going to Mary Harriman Rumsey’s house for a party, which in turn brought to mind a hideous night at the Mackays’, when Ring Lardner wouldn’t leave the cloakroom.

The Mackays were an immensely wealthy family with an estate in nearby Roslyn, Long Island. Fitzgerald’s ledger records a party there in June 1923; Zelda saved an invitation from the Mackays for Sunday, July 8, 1923. Clarence H. Mackay’s daughter Ellin was a famous heiress who rejected her debutante lifestyle, and in 1926 shocked the nation and her family by marrying a Jewish immigrant, fifteen years her senior, named Irving Berlin, the most famous composer in America. Her Catholic father threatened to disinherit Ellin, but they were reconciled some years later; as fate would have it, Irving Berlin would bail out his father-in-law during the Great Depression. Within twenty years, people in “the show business” were buying up the older American aristocracy.

In “My Lost City,” Fitzgerald uses Ellin Mackay’s marriage as a milestone that defined the twenties’ union of high and low culture. By 1920, “there was already the tall white city of today, already the feverish activity of the boom,” he wrote, but “society and the native arts had not mingled—Ellin Mackay was not yet married to Irving Berlin.” But then over the next two years, “just for a moment, the ‘younger generation’ idea became a fusion of many elements in New York life . . . The blending of the bright, gay, vigorous elements began then . . . If this society produced the cocktail party, it also evolved Park Avenue wit, and for the first time an educated European could envisage a trip to New York as something more amusing than a gold trek into a formalized Australian bush.”

Why Ring Lardner hid in the cloakroom at the Mackays’ estate one summer night has been lost to history, however.

Five years later, Lardner sent the Fitzgeralds another Christmas poem:

We combed Fifth Avenue this last month

A hundred times if we combed it onth,

In search of something we thought would do

To give to a person as nice as you.

We had no trouble selecting gifts

For the Ogden Armors and Louie Sifts,

The Otto Kahns and the George E. Bakers,

The Munns and the Rodman Wanamakers

It’s a simple matter to pick things out

For people one isn’t wild about,

But you, you wonderful pal and friend, you!

We couldn’t find anything fit to send you.

The following Christmas, Scott responded in kind:

You combed Third Avenue last year

For some small gift that was not too dear,

—Like a candy cane or a worn out truss—

To give to a loving friend like us

You’d found gold eggs for such wealthy hicks

As the Edsell Fords and the Pittsburgh Fricks,

The Andy Mellons, the Teddy Shonts,

The Coleman T. and Pierre duPonts.

But not one gift to brighten our hoem

—So I’m sending you back your Goddamn poem.

It seems the Fitzgeralds spent Christmas Day 1922 in Great Neck; Zelda wrote to Xandra Kalman in early January saying they’d had “astounding holidays” which began “about a week before Christmas” and didn’t end until January 5, when she was writing her letter.

If Fitzgerald managed to read the book section of the New York Times that Christmas weekend, he would have seen an editorial on fiction writing and the facts, as he mused over his new novel: although “fiction writers have emancipated themselves from many restraints, as to both form and content,” they still had to come up with their own plots. “They are, of course, at liberty to use so much material from real life as can be incorporated without danger of libel; but such material needs so much working over before it can become plausible fiction that it entails about as much effort as inventing plots offhand.”

What if invention is not a question of effort, however, but of meaning? When The Great Gatsby was reissued in 1934, Fitzgerald wrote a preface, saying that he had never tried to “keep his artistic conscience as pure” as during the ten months he spent writing the novel in 1924. “Reading it over one can see how it could have been improved—yet without feeling guilty of any discrepancy from the truth, as far as I saw it; truth or rather equivalent of the truth, the attempt at honesty of imagination. I had just re-read Conrad’s preface to The Nigger [of the “Narcissus”], and I had recently been kidded half hay-wire by critics who felt that my material was such as to preclude all dealing with mature persons in a mature world. But, my God! it was my material, and it was all I had to deal with.”

The aim of art, wrote Conrad in the preface, is “by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel—it is, before all, to make you see . . . If I succeed, you shall find there according to your deserts: encouragement, consolation, fear, charm—all you demand; and, perhaps, also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask.”

Fitzgerald often had this passage in mind as he wrote; in 1923, he quoted it in a letter: “As Conrad says in his famous preface, ‘to make you hear, to make you feel, above all to make you see . . .’” He had reread the preface again as he wrote Gatsby. Fitzgerald was thinking about his materials, what he had to work with, as he tried to offer a glimpse of the truth for which his audience had forgotten to ask. Critics told him that his material was inessential, scarcely created—but facts are always merely material, until someone shines what Conrad called a light of magic suggestiveness on them. When he sailed for France in 1924, Fitzgerald had decided that his project would be to “take the Long Island atmosphere that I had familiarly breathed and materialize it beneath unfamiliar skies.” He materialized it, made it material, and made it real—and then he made it matter.

By the time he wrote “How to Waste Material—A Note on My Generation” in 1926, Fitzgerald had begun to think of a writer’s material as capital; later he said that he’d made “strong draughts on Zelda’s and my common store of material.” Their life together was like a joint bank account, upon which only one of them could afford to draw. But thinking about his life as capital for art proved a dangerous business. As Fitzgerald, of all people, should have understood, Mammon is a treacherous god. “There is no materialist like the artist,” wrote Zelda later, “asking back from life the double and the wastage and the cost on what he puts out in emotional usury. People were banking in gods those years.”

The sculptor Théophile Gautier once said that his sculptures became more beautiful if he used a material that resists being sculpted—marble, onyx, or enamel. The same may be true for writers, sculpting their own resistant material, struggling to release the angel from the rock. Near the end of his life, Fitzgerald wrote that once he had believed that his writing should “dig up the relevant, the essential, and especially the dramatic and glamorous from whatever life is around. I used to think that my sensory impression of the world came from outside. I used to believe that it was as objective as blue skies or a piece of music. Now I know it was within, and emphatically cherish what little is left.” He no longer thought that his material was capital, but that his artistry was—and he had wasted it.

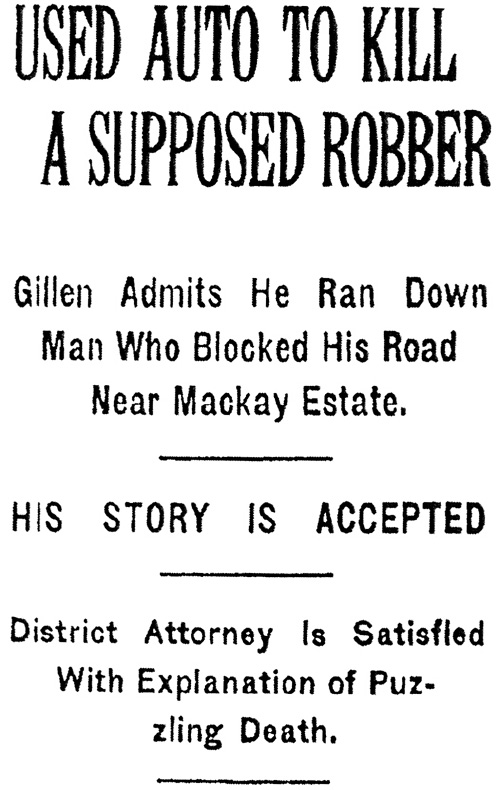

Christmas over, the New York Times reported in late December 1922 that “the puzzling death” of Phillip Carberry, a car salesman “whose bruised body was found on the road near the Clarence H. Mackay estate,” was solved the day after Christmas. A man named Lester J. Gillen admitted “he had run down a man standing in the road, presumably Carberry, in the belief that he was a robber who was trying to hold him up.” So he had accelerated and deliberately run him over. The district attorney “indicated his satisfaction” with the story, reported the Times. Gillen explained that he and his passenger “did not stop, because we believed our lives in danger,” and that seemed to be sufficient justification for running Carberry over.

In March 1924 Fitzgerald published an article about young people in America, in which he noted that a rich young American “thinks that when he is arrested for running his car 60 miles an hour he can always get out of trouble by handing his captor a large enough bill—and he knows that even if he has the bad luck to run over someone when he’s drunk, his father will buy off the family and keep him out of jail.” He seems to have had good reason for making this generalization.

When George Wilson begins to mutter that his wife was deliberately run down in the road by the gaudy yellow Rolls-Royce, Michaelis tells him, “You’re morbid, George . . . This has been a strain to you and you don’t know what you’re saying.” George repeats, “He murdered her.”

“It was an accident, George.”

Wilson shook his head. His eyes narrowed and his mouth widened slightly with the ghost of a superior “Hm!”

“I know,” he said definitely, “I’m one of these trusting fellas and I don’t think any harm to nobody, but when I get to know a thing I know it. It was the man in that car. She ran out to speak to him and he wouldn’t stop.”

Michaelis had seen this too but it hadn’t occurred to him that there was any special significance in it.

Maybe George isn’t nourishing morbid pleasures, or deluded, after all. Perhaps he has just been reading the papers, and begins to see special significance where others don’t.

Wilson tells Michaelis that when he got “wised up” to Myrtle’s affair, he’d marched her over to the window, where they could see the pale, enormous eyes of T. J. Eckleburg staring down at them, and confronted her with her guilt: “I told her she might fool me but she couldn’t fool God. I took her to the window . . . I said, ‘God knows what you’ve been doing, everything you’ve been doing. You may fool me but you can’t fool God!’” “God sees everything,” Wilson adds.

“That’s an advertisement,” Michaelis assures him.

Burton Rascoe declared in December 1922 that nostalgia “is one of the oldest of fallacies.” Even Aristotle, he pointed out, was lamenting that “the theater is no longer what it used to be, that standards are being trodden upon, that the rabble is being catered to.” And so, in forty more years, Rascoe predicted, perhaps “Scott Fitzgerald will be flooding his whiskers with tears of sorrow over the decline of morals since the Jazz Age.” Such a prospect was not so “chimerical” as some might think, he insisted. The Fitzgeralds had already begun their holiday celebrations by the time the article appeared, which may account for Fitzgerald missing this mention: it is not in his scrapbooks.

As The Great Gatsby draws to a close, Nick Carraway remembers returning home to the Midwest for Christmas from his schools in the east. In Chicago, he changed trains for St. Paul. “When we pulled out into the winter night and the real snow, our snow, began to stretch out beside us and twinkle against the windows, and the dim lights of small Wisconsin stations moved by, a sharp wild brace came suddenly into the air. We drew in deep breaths of it as we walked back from dinner through the cold vestibules, unutterably aware of our identity with this country for one strange hour before we melted indistinguishably into it again.”

“That’s my Middle West,” Nick says, “not the wheat or the prairies or the lost Swede towns but the thrilling, returning trains of my youth and the street lamps and sleigh bells in the frosty dark and the shadows of holly wreaths thrown by lighted windows on the snow.” The thrill is in the return. This requiem to the dark fields of the snowy republic is the moment when The Great Gatsby begins to converge with the emotion that drives the great Gatsby and destroys him: nostalgia, the wistful longing to recapture the past, the expelled Adam seeking a route back into Paradise. A nation so fixed on progress will always be pulled, Nick begins to see, back into nostalgia, reaching for what lies ahead yet longing for what lies behind. This is what it means to be American, Nick concludes: to sense our identity with this country even as we lose our place in it. Before we even grasp it, it is gone, leaving us buffeted by a deep wave of nostalgia, rippling through us like the cold night air. If its faith in progress represents America’s hope in the future, then nostalgia is its hope in the past.

For all its sparkling modernism, The Great Gatsby is colored with nostalgia, peopled with characters carrying well-forgotten dreams from age to age. Although Gatsby is more driven by nostalgia than anyone else, he is by no means the novel’s only nostalgic character. Even Tom wistfully seeks “the dramatic turbulence of some irrecoverable football game.” Only thoroughly modern Jordan is immune to it.

Fitzgerald never became a whiskered old man, although he certainly managed some pungent remarks on the decline of standards as he grew older. In 1940 he sternly wrote to his daughter about her projected course of study at Vassar. He hated to see her spend tuition fees “on a course like ‘English Prose since 1800,’” he told her. “Anybody that can’t read modern English prose by themselves is subnormal—and you know it.”

To Scott Fitzgerald’s contemporaries he was the voice of the eternal present, but now he is the voice of nostalgic glamor: lost hope, lost possibility, lost paradise. Rascoe guessed right, but for all the wrong reasons: Fitzgerald would become the American twentieth century’s greatest elegist. Nostalgia is a species of faith. “Like all your stories there was something haunting to remember,” Zelda told Scott later, “about the loneliness of keeping Faiths.”

Gatsby is left at the end of the chapter, watching over nothing. Dawn breaks jaggedly, like a crack in a plate.