Positive Psychology

At a recent community lecture on positive psychology, the speaker introduced a familiar catch phrase: “control > alt > delete.” He went on to explain that this represented the sentiments of an acquaintance who framed her disability as follows: “I can control my thoughts > there are always alternatives to how I see things > and I can choose to delete what I don’t need.” This was her attempt to utilize positive strengths and develop a foundation for wellness in light of her recent adjustment to a disability.

Positive psychology, introduced by Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000), is a corrective response to psychology’s emphasis on pathology. The main aim is to develop a focus on wellness—rather than disorder—in order to capture a more realistic appraisal of life experience and what it means to be human. At the subjective level, the field of positive psychology focuses on valued experiences, well-being, life satisfaction, and hope. From a personal view, this entails a focus on positive individual traits, and from a group level, valued citizenship (Kashdin and Ciarrochi, 2013).

Positive psychology is often referred to as the “science of happiness.” But happiness doesn’t mean that everything in life will necessarily be good, happy, or desirable. In the normal scheme of things, we have a balance of positive and negative life experience. Furthermore, our innate bias toward survival means that we tend to gravitate toward and focus on negative experience when they happen (Hanson, 2013).

In positive psychology, mindfulness helps to increase equanimity and concentration by focusing on character strengths to mobilize resources, and cultivate health and well-being. Whereas earlier proponents of positive psychology focused mainly on positive and negative strengths, and attributes to effect change, more recent followers have sought a more dynamic approach to well-being. Moving beyond superficial notions of positive and negative experience, practitioners now tend to adopt the approach of focusing on all elements that may lead a person to living well. For example, people who suffer from anxiety often use control strategies (rituals, routines) to ensure they will not have to face what they fear or feel uncomfortable with. These avoidance strategies, if successful, soon become habitual and automatic, reinforcing maladaptive cycles of negative or catastrophic self-talk. This is where mindfulness can be used skillfully to show clients how they can replace their need for control (avoidance) with the capacity to take control (adaptive coping).

A useful metaphor in this instance might be to suggest that a client see themselves as the director of a play taking place in the mind. They can choose which thoughts play center stage, which are just out of sight in the wings, or which get banished to the backstage! Noticing thoughts, feelings, and sensations is the first step in becoming present and developing a relationship with the internal world. Making choices about how to respond is the second, and affects how we relate in the world. Though seemingly paradoxical, by drawing on a client’s need for control (rigid thinking), their proficiency for control can also be used as a strength or sensibility for skillfully enhancing cognitive flexibility.

Veronica

Veronica, a woman in her fifties, came to therapy to sort out “what she wanted in life.” This was her goal. Having recently retired as a carer for elderly end-of-life patients, she was emotionally burnt out. Veronica was keen to explore and develop her “authentic self” in therapy. On the one hand, Veronica sensed that “she was blocked by her ego;” on the other, she felt that “she didn’t know what she wanted to do, or how to change her life.” Her frustration was palpable when she spoke of it.

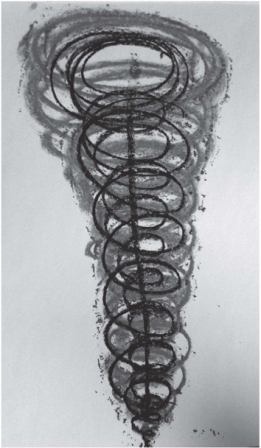

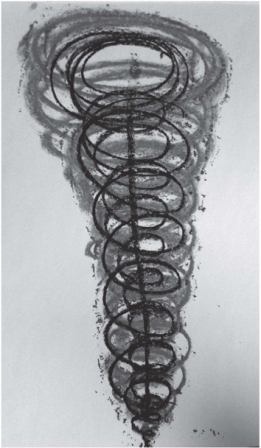

In the first session, Veronica struggled to calm her anxiety, but eventually did so by attempting to engage in breath work. When the guided meditation finished, her pent-up frustration spilled onto the page in swirling red and black chaos that resembled the shape and character of a tornado (Figure 16.1).

Figure 16.1 Chaos (see color plate)

Bold, sweeping circles embodied the frustration of key childhood events whose resonance continued to play out in her life. Reflecting on the image, Veronica seemed in a rush to disclose past events so she could move on from them. She mentioned that she was ready to shed the outdated feelings embodied in this artwork in favor of transforming it in ways that “would make life better.” She then asked if she could continue to work on the image.

Despite the importance of processing this first image with Veronica, I equally sensed the urgency with which she seemed to need to move forward with it. Fortunately, with the advent of photography, I was able to capture the first image shown here (embodied frustration) before Veronica spontaneously transformed it into “something more positive and hopeful” in a matter of minutes.

Figure 16.2 Grapes (see color plate)

This second image (Figure 16.2) represents “the fruit of life [grapes], complete with light [sunshine] and personal growth [leaves].” Reflecting on the image gave Veronica hope and confidence that the possibilities for change were within her. Consistent with current trends in neuroscience and positive psychology, this shows how clients can begin to attempt to hold positive and negative emotions simultaneously in order to develop adaptive emotional responding (Hanson, 2009; 2013).

Both images provided crucial symbols for exploring the inner division between Veronica’s frustration and hope. Highlighting both the problem and the solution, we explored the dichotomies of how life threatened to spiral out of control contrasted with Veronica’s innate sense of hope that it wouldn’t and her capacity for resilience.

Through concerted efforts to calm herself mindfully, Veronica was able to access the deeper energy of her frustration and begin to reflect without attaching to it. Processing the psychological and therapeutic aesthetic dimensions through art was important in providing a context for exploring the energy she brought to it. Her ongoing visual dialogue through spontaneity—from the first image to the second—further provided Veronica with opportunities for authentic disclosure through the power of the images. By tangibly expressing past and future, this helped bridge the ambiguity between thinking, feeling, and behavior and also illustrates how art provides a visual voice when thoughts rush in or ideas overwhelm.

Landgarten’s (1975) notion of personal symbology comes to mind here in highlighting the importance of clients sharing their personal meanings in therapy. But this begs the question: “Are strengths inherently positive?” (Kashdin and Ciarrochi, 2013, p.39). Aesthetic dimensions of therapy enabled Veronica to be free through the art, whereas both images highlighted the emotional tensions that competed for “living authentically,” which was Veronica’s goal for therapy.

The contrast between image one (frustration) and image two (resilience) gave us a tangible basis through which to instill some mindfulness principles of positive psychology to foster her resilience despite past and present disappointments. An awareness of the positive life experiences and attributes in which to anchor this resilience enabled Veronica to begin to free herself from the negative energy that threatened to overwhelm, and keep her stuck in the past.

Transforming the original image into something more valued (signaling her need to get it right and move on) (McNiff, 2004), enabled Veronica to reflect simultaneously on old issues, new strivings, and create a direction for moving forward. This path for authentic disclosure enabled Veronica to capture a network of memories, associations, events, and feelings through the images (Rennie, 2002). This marked a point where our “true” therapy could begin.