There Are Witches in the Air

It was once the custom of Austrian farm wives to go out to the orchard at midnight on St. Andrew’s Eve (November 29) to break branches from the apricot trees. They forced the branches into flower in vases at home, then carried them to church on Christmas Eve. The white blossoms must have looked quite striking against the wives’ dark wool Sunday dresses, but it was not these ladies’ intention to create a pretty tableau; the flowering apricot branch allowed the bearer to pick out any witches in the congregation. What set the Austrian witch apart? Well, if you had an apricot branch, you would notice she carried a wooden pail on her head. I don’t know about witches, but the practice must have been an effective means of identifying the parish busybodies.

St. Andrew’s Day is an important fingerpost along the road to Christmas. There are two systems in place for calculating the beginning of Advent, the ecclesiastical Christmas season. One is to count back from the fourth Sunday before Christmas Day. The other is to locate the Sunday closest to St. Andrew’s Day. In most Catholic and formerly Catholic regions, St. Andrew’s Day is the cue to start planning a happy holiday, but it is the darker occasion of St. Andrew’s Eve, and the ensuing Christmas season, which concerns us here.

Vampires

While the Austrian witches were scouring their milk pails and Polish girls were busy pouring lead into cold water to find out when and to whom they would be married, the Romanians had bigger problems. In Romania, St. Andrew’s Eve was not a night to go out, let alone to go wandering in the orchard. It was not enough to lock the doors; before dark, all apertures had to be thoroughly rubbed with a peeled garlic clove, for on this night the vampires clawed their way out of their graves and walked again. Carrying their coffins portage-style, they paraded into the village to circle their former homes before taking themselves to the crossroads to engage in a pitched battle, no doubt with the vampires of the neighboring village.

A cross placed, chalked, or painted over a door or cattle stall imparts protection to the occupant, but a crossroads has always been the haunt of witches and other “malevolent” spirits, perhaps because suicides were buried and outlaws left to rot there. The Apostle Andrew, whose night this is, was martyred on an X-shaped cross. His feast day marks a crossroads within the year, for it was acknowledged in much of Europe as the true beginning of winter.

Joining these more usual vampires at the crossroads were the village’s congenital vampires. This could be a seventh son or an individual whose mother had neglected to pull out the one or two teeth with which he had been born. The soul of this kind of vampire left his sleeping body as a blue flame flying out through the mouth. Between home and the crossroads, it assumed the shape of that vampire’s personal animal, so even the nosy neighbor who was brave enough to peer out the window would have no idea to whom the fiery blue dog flying by might belong. Cockcrow sent both species of vampire scuttling back to their graves and their beds on the morning of St. Andrew’s Day.

In his mammoth work The Golden Bough, Sir James George Frazer describes another sort of “vampyre” afoot in Romania. This one might be kept at bay with the “need fire,” which was kindled afresh after all fires in the community had been extinguished. The need fire was used to purify and protect the cattle from diseases that these vampires were thought to cause. Unlike Bram Stoker’s or Stephenie Meyer’s undead, these vampyres were incorporeal.36 Frazer contrasts them with “living witches,” classing them instead with “other evil spirits.” Though filtered first through German and then through French, the term vampire arrived in English almost untouched from Serbian. The word is so old that its etymology is uncertain, though it may have come from the Turkish ubyr, which means simply “witch.”

Down with a Bound

Long before the introduction of “floo-powder,” there was already a lot of coming and going through the fireplace flue as the witches floated very nimbly both up and down the chimbley. In Somerset, the general consensus was that witches could not walk through walls at Christmas or at any other time of the year; that was for ghosts. Most often, witches entered the house through the door or window just like everyone else. White or gray witches were able to walk in the church door to attend Midnight Mass, but black witches had to stay outside or risk becoming distinctly unwell. The Somerset witch’s favorite route, however, was through the chimney, and in this she was not alone.

In Norway, too, Christmas Eve was a great traveling night for witches. Not just brooms but stools, staves, and fireplace tools were hidden away to prevent the witches from stealing and riding them. This, of course, was no obstacle to the witch who possessed an Icelandic witch’s bridle, for she could transform anything, even a washboard, into a fast-moving vehicle just by laying the bridle upon it. Where there’s a witch, there’s a way, and many of them probably kept their own stashes of extra broomsticks under the floorboards or in secret cupboards under the stairs.37 The typical folkloric witch also had a hornful of flying ointment with which she could anoint household objects to make them hover in the air like spaceships.

Knowing all this, Norwegian peasants spent the darkest hours of Christmas Eve trying to shoot the witches out of the sky like pigeons. But if you wanted to save your buckshot, all you really had to do was call out the names of suspected witches, causing them to fall in mid-flight. Where were all of these witches supposed to be going? The bright meadows of Jönsås, a mountain in eastern Norway, were a popular destination at Easter and Midsummer, but on Christmas Eve, the place to be was “Blue Knolls.” There, all the witches who had signed their names in the big book belonging to “Old Erik,” as the Devil was fondly known, gathered in the snow to hold their own feast apart from the Christian folk on the farms below.

In his childhood memoir, When I Was a Boy in Norway, Dr. J. O. Hall claims that the English Yule log was originally a Norwegian import. If this is true, then the idea that the ashes of the Yule log will keep witches away probably also came from Norway. The Norwegian housewife who was still worried about witches sliding down the chimney on Christmas Eve could throw salt on the flames of the Yule log, for there was nothing like a blue fire to deter a witch.

While the presence of a glittering Christmas tree was not enough to keep a witch out, dried spruce boughs laid on the fire might, for the dry needles created an explosion of sparks that frightened the witches away. Today, firecrackers are used to the same end, but are they as effective? It may not have been just the flash and the noise that was supposed to put the witches off but the concentrated essence of evergreen. Throughout Europe, on all the most dangerous nights of the year, the farmer made the rounds of his outbuildings with a brush and a bucket of pine tar, for the vigorously turpentiney scent of pine tar, which many of us find pleasantly heady, is apparently repellent to witches.

Scandinavians have been distilling tar from the split roots of Pinus sylvestris since time out of mind. In the old days, the distillation process took place in earth-covered kilns in the forest, so perhaps Snorri Sturluson’s dark elves were actually ancient kiln-watchers. The Norsemen used pine tar to waterproof their boats when they went a-viking, using the leftovers in the bucket to paint black crosses, or in those days Thor’s hammers, above the farmhouse door and above each stall in the cow byre. Just about anywhere in Europe where pine trees grew, pine-tar crosses were painted at strategic points around the homestead. Such crosses could be stroked onto the beams at any time, but they should be given a fresh coat at Walpurgis Night, Midsummer, and, of course, Christmas Eve.

Rise of the House of Knusper

On December 23, 1893, Engelbert Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, a “fairy opera,” premiered at the Hoftheater in Weimar with Richard Strauss conducting. This was the beginning of a Christmas tradition that has lasted to this day, but it was also the most recent development in an older, edible Germanic tradition. Eighty-one years earlier, the story of Hansel and Gretel first appeared in print in Household Stories by the Brothers Grimm. “Hansel and Gretel,” the fairy tale, is an example of Tale Type 327, in which a child or children defeat an ogre or witch. Tale Type 327 is found all over Europe, so who knows how old it might be? One theory is that it grew out of the Great Famine of 1315–1320, but this theory overlooks the fact that poverty and hunger were ongoing issues for peasant families until very recent times.

Even before the opera’s premiere, “Hansel and Gretel” was considered a Christmas story, perhaps because it featured an edible house.38 The Brothers Grimm say only that the witch’s house “was built of bread and roofed with cakes,” but few Germans would consider building a witch’s house out of anything but Lebkuchen. What is the difference between Lebkuchen and gingerbread? Lebkuchen, which is eaten in many shapes throughout the Christmas season, contains no ginger. The Lebkuchenhäuschen, which also goes by the names Hexenhäuschen (“witch’s cottage”) and Knusperhäuschen (“crunchy cottage”), and even “Knisper-Knasper-Knusperhaus,” as it is referred to in Act I of the opera, is a staple of the German, Swiss, and Austrian Christmas. In the folk song “Hänsel und Gretel,” of uncertain date, the witch’s house is made of Pfefferkuchen, another ubiquitous German Christmas cookie that comes coated in hard white icing. So perhaps the snow-bedecked witch’s house represents a Christmas tradition independent of either the Grimms or the Humperdincks.

It was the composer’s sister, Adelheid Wette, who, working from the Grimms’ story, wrote a poem about Hansel and Gretel for her children to perform at home on Christmas. No doubt this was one of those dreaded recitations that many German children are still forced to deliver in front of the decorated tree on Christmas Eve. In Adelheid’s version, the mother sends the children out in a fit of temper; it’s not premeditated abandonment. She is not nearly as heartless as the stepmother in the Grimms’ version of the story, who sniffs, “Better get the coffins ready!” when the children’s father balks at her plan. Just to confuse the issue, many productions cast the same singer as both the mother and the witch. At other times, the witch may be sung by a male tenor, while the role of Hansel is often sung by a woman.

The opera does not actually take place at Christmastime; the only fir trees are the ones clustered at the foot of the Ilsenstein where the witch’s cottage appears. In the first act, the father, a broom-maker, mentions that the villagers are preparing for a feast. This is probably St. John’s Day, or Midsummer, since his children are at the same time picking wild strawberries39 at the foot of the aforementioned Ilsenstein, a knobbly stone protuberance poking its head out of the dark forest of the Harz in order to get a good look at the nearby Brocken, a mountain known by all Germans to be heavily frequented by witches. Coming home drunk, the father boasts to his wife that he has sold his entire stock of besoms. One cannot help but wonder if he might have sold one of them to the Nibbling Witch, who will soon try to cook his children, for the Nibbling Witch likes to circle her house on a broomstick.

If you don’t already know how it all ends, or even if you do, you can host a showing of Hansel and Gretel at home. There are a number of productions from which to choose. You might try the 1998 DVD Hänsel und Gretel directed by Frank Corsaro, in which the sets and costumes are designed by Maurice Sendak. (I, for one, would not dare to take a bite out of Sendak’s witch’s house no matter how hungry I was; it has eyes!) Unfortunately, there is no DVD of Tim Burton’s live-action, strongly Japanese-flavored Hansel and Gretel, which appeared on the Disney Channel on Halloween 1983. Like most of the world, I’ve never actually seen Burton’s version, but it can’t be any creepier than the 1954 stop-action Hansel and Gretel: An Opera Fantasy directed by Michael Myerberg. For movie snacks, I suggest almonds and raisins, the foods the witch fed to Hansel to fatten him up.

Craft/Recipe: Lebkuchen Witch’s House

Craft/Recipe: Lebkuchen Witch’s House

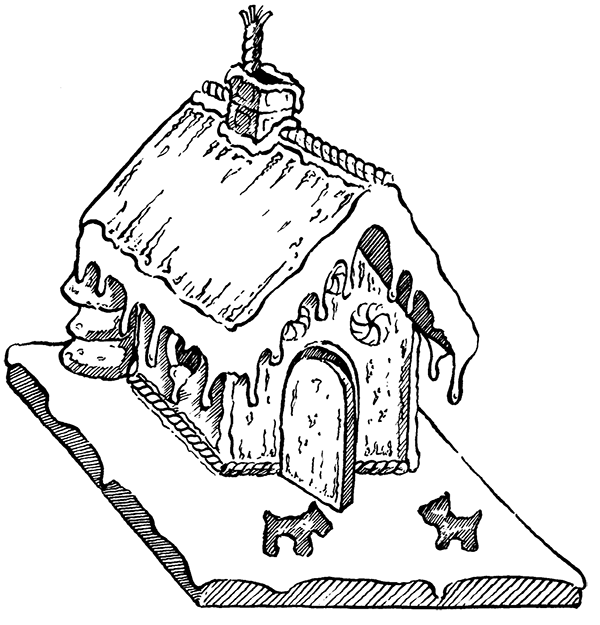

Before you decide that this project is too much for you, keep in mind that Lebkuchen is rolled out much thicker than gingerbread cookie dough. These thicker walls make the house quite easy to assemble.

The following instructions will make one Witch’s House about 4 inches high, 4½ inches wide, and 6 inches long in a garden that’s about 5½ inches wide and 8 inches long, with a little dough left over for details like shutters, paving stones, animal familiars, or whatever else you can dream up. Or, you can bake the extra dough into cookies for immediate eating. Because I like a hollow chimney through which smoke can escape, I build mine out of dark chocolate segments. My German grandmother, however, made hers out of a solid, heavy piece of dough. When the chimney fell in, it was time to eat the house.

Overhanging eaves are another hallmark of the traditional Witch’s House. This leaves lots of room for icicles, which can be made with a quick sweep of a fork or knife. Since this is a humble, homemade sort of cottage, you will not be called upon to wrestle with a pastry bag.

In Germany, the door of the Witch’s House is usually left ajar to entice Hansel and Gretel inside. An open door also allows you to put a tea light inside to illuminate the windows, which can be glazed with dried lemon or orange slices, Fruit Roll-Ups, or—my personal favorite—small sheets of roasted seaweed. If you make a hollow chimney, the smoke from the blown-out tea light will drift up through it.

The green seaweed windows combined with a lot of black licorice accents will convey a sense of poorly suppressed witchiness. I have placed two Trader Joe’s Black Licorice Scottie Dogs in my garden along with a chocolate Christmas tree for their convenience. (You could also put a few black licorice cats on the roof.) For a final touch, I snipped the end of a black licorice stick into a brush and left it sticking out of the chimney. We can only hope that the chimney sweep to whom it belonged did not end up in the witch’s oven!

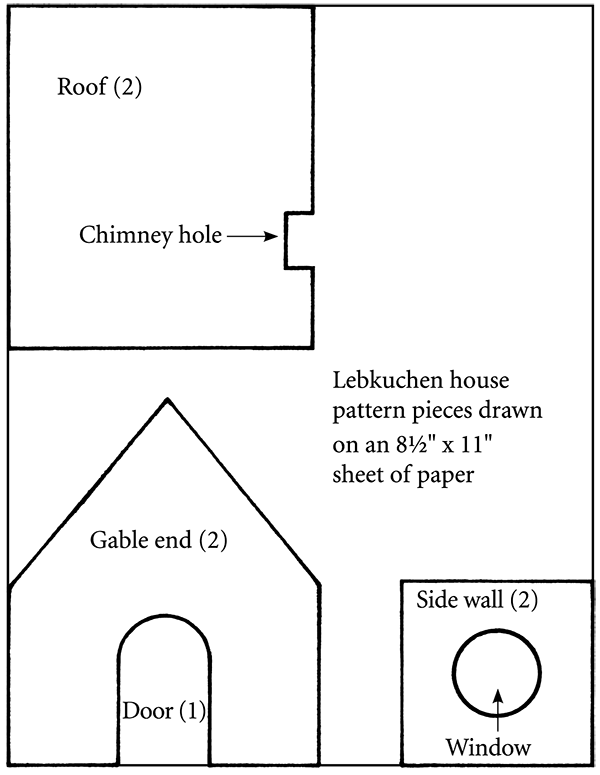

Step 1: The Template

All you need to make a template is a sheet of 8½" x 11" paper, a pencil, and a pair of scissors. Draw the pieces as shown or enlarge on a photocopier. (You don’t have to cut out the window in the side wall; you can use a water-bottle cap to cut it out of the dough later.) Cut out all your template pieces and set them aside before you make your dough.

Lebkuchen Witch’s House, figure 10.1

Step 2: The Dough

Ingredients:

5 Tablespoons unsalted butter, softened

1½ cups sugar

2 eggs, gently beaten

Zest of one lemon

½ teaspoon ground cloves

½ teaspoon nutmeg

1½ teaspoons cinnamon

½ cup ground almonds

3 cups flour

2 teaspoons baking powder

2 Tablespoons milk

Cream butter and sugar together in a large bowl. Stir in eggs, lemon zest, spices, and almonds. Add flour and baking powder a little at a time, adding the milk as the dough stiffens. You will have to work the last half-cup of flour in with your hands. When it’s all mixed, shape it into a loaf, wrap in plastic, and refrigerate until you are ready to cut out and bake the pieces of your house. If you’re ready right now, proceed to step 3.

Step 3: Cutting and Baking

If you have refrigerated the dough, leave it out at room temperature for at least an hour before beginning. When you are ready, preheat oven to 425°F.

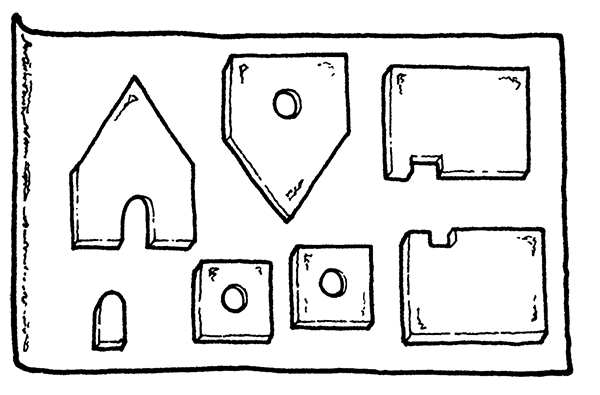

Roll the dough out to ¼-inch thickness. Place your template pieces on the dough and cut around each with a sharp knife. Placing the template pieces as close to each other and as close to the edges of the dough as possible will minimize the number of times you need to roll out the dough. Remember: you need two gable ends, two roof pieces, and two side walls. You can add a window in the gable end without the door.

Lebkuchen house pieces laid out on a cookie sheet

Lebkuchen Witch’s House

When all the house pieces are cut out, roll and cut out your garden.

Place all the pieces carefully on one or more cookie sheets lined with nonstick foil and bake for 15 minutes or until golden brown. If in doubt, it’s better to over-bake them than to under-bake them. Here’s one rule of thumb: when your kitchen starts to smell like the Old World Christmas, your Lebkuchen is almost done.

Let the pieces cool completely before you make the icing and assemble the house. You can even put the pieces in a tin and pick them up again the next day.

Step 4: The Icing

The icing is your snow as well as the glue that will hold your house together. This recipe makes more than enough, so don’t be stingy with it. Also, don’t worry if the finished house looks a little gloppy; that’s how your friends will know you made it yourself.

Ingredients:

2 egg whites

¼ teaspoon cream of tartar

2 cups powdered sugar

Beat the egg whites with the cream of tartar until the mixture foams. Add the sugar a little at a time, beating on low speed. Continue beating a few more minutes until the icing hangs from the beaters but does not drip off.

Step 5: Assembly and Decoration

First, spread the yard with a thick layer of icing. Press one gable wall and adjacent side wall into the icing, cementing the corner with more icing. Check that they are standing straight, then add the remaining two walls and the open door. Let the icing dry about 20 minutes before gluing the roof on. Cover the bowl of icing with plastic wrap to prevent any crust from forming. While you are waiting for the walls to dry, glue your choice of fruit or seaweed inside the windows.

Lebkuchen Witch’s House

After you have cemented the roof pieces in place, you can assemble the chimney. Cut the chocolate pieces at a slant to match the slope of the roof. You don’t have to be too precise; a healthy slather of icing will cover any mistakes.

Use the rest of the icing for icicles and to glue on any decorations. The possibilities are endless. I am partial to the aforementioned licorice pets and sticks as well as licorice allsorts and starlight mints.

Step 6: Eating

Though you might need a hammer, there’s no reason why you can’t eat this house when Christmas is over. In fact, it’s a good excuse for a party. Hold each shard of house over a steaming cup of coffee or tea to soften it. The seaweed window panes can be easily peeled off, since Lebkuchen and seaweed together is not a taste that can be acquired by all.

Witches Bearing Gifts

There was a time when it was considered godly to walk around in a flea-infested hair shirt, while cleanliness was next to witchiness. To this day, the Italian witch Befana pays the price for her overzealous housekeeping each Epiphany Eve when she flies over the rooftops on her broomstick, searching for the Baby Jesus. Like the other Midwinter Witches who have been renamed for saints, Befana’s name is a slurring of her feast day, Epiphania, which comes from the Greek for “manifestation.” Though Befana is now a thoroughly Christian witch, she remains a manifestation not just of that shining star over Bethlehem, but also of the old winter goddess who used to be abroad at Yuletide.

Befana had the chance to meet the Holy Family in person way back in the first century when the Three Kings stopped to ask for directions, but she was too busy sweeping the dust from her dooryard to pay the glittering company any mind. Of course, as soon as they rounded the bend, she had a change of heart and decided she really would like to bring a gift to this bright young baby. By the time she had changed her clothes and baked a batch of pefanino, or Epiphany biscuits, the caravan had passed out of sight. So began her two-thousand-year quest to locate and present her gifts to the Baby Jesus.

In Italy and the Italian-speaking regions of Switzerland, it is Befana who delivers the presents on the night of January 5. In Sicily, she goes by La Vecchia di Natale, the Old Christmas Woman, and comes on Christmas Eve—if, that is, she has not been preceded down the chimney by a sooty Lucia on the night of December 12. Usually, Befana simply pours the toys down the chimney, into the polished boots and striped stockings the children put out before they go to bed. How does Befana know what they want? Magic: the children write their lists on slips of paper in front of the fireplace and let them waft up the chimney and into the sky, where Befana deftly catches them.

Sometimes, the old hag comes inside to get a good look at the children themselves. One of these nights, she hopes, she’ll finally meet up with the Christ Child. In the meantime, she’s not above taking the naughty ones and eating them, though this aspect of her character has been played down in recent years. In the nineteenth century, the children of the house used to dress a rag doll as a witch and set it in the window on Befana’s Eve. Today, you can still buy carved or stuffed Befanas at the Christmas markets in Italy.

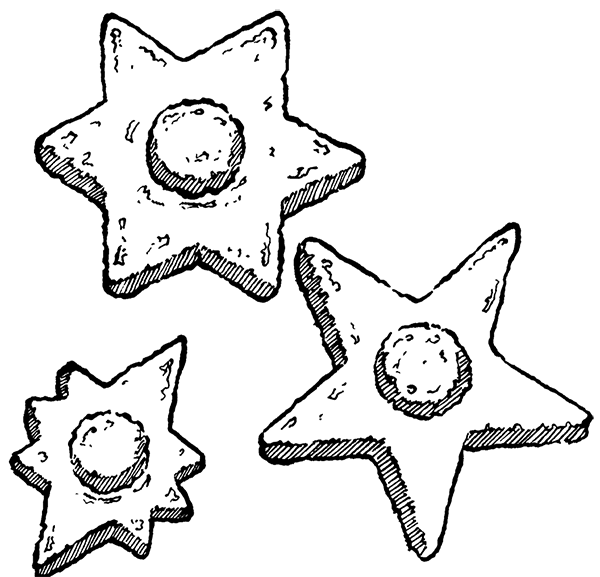

Recipe: Befana Stars

Recipe: Befana Stars

The pefanino of earlier days was either round or shaped like Befana herself on her broomstick. If you are lucky enough to own a witch-shaped cookie cutter, go for it. Otherwise, the more contemporary star shape will do. Yes, I do realize that you’re busy cleaning house after a frantic Christmas season, but take a hint from Befana, put down the broom, and bake some cookies.

For the dough:

1 stick (8 Tablespoons) unsalted butter, softened

¾ cup sugar

1 whole egg plus one egg yolk (reserve white for topping)

Zest of one clementine or small orange

Zest of one small lemon (use half for the dough, reserve other half for topping)

½ teaspoon vanilla extract

½ teaspoon anise extract

2 cups flour

½ teaspoon baking powder

Cream the butter and sugar together, add egg yolk, and stir well. Mix in zests and extracts. Add the baking powder to the flour and mix with the rest of the ingredients a little at a time. When the dough is smooth, form it into a ball, wrap it in plastic wrap, and refrigerate it for at least one hour.

For the topping:

1 egg white

¼ cup sugar

Remaining lemon zest

½ cup ground almonds (or you can use sliced almonds and chop them very fine)

Powdered sugar

In a deep, medium-sized bowl, beat the egg white and sugar until stiff. Fold in lemon zest and almonds. Set aside.

Roll out the dough to 1⁄8-inch thickness on a floured surface and cut into star shapes. Lay stars on a greased or parchment-lined cookie sheet and drop a dollop of topping in the center of each star. Bake at 350°F for 13 minutes or until star points and topping are golden brown.

Dust cookies with powdered sugar while they are still warm.

Befana stars

36. For a thorough treatment of some distressingly corporeal vampires, see Paul Barber’s book Vampires, Burial, and Death, if you have the stomach for it.

37. Such a stash was discovered in an old house in Wellington, England, in 1887, when demolition work revealed a hidden room inside the attic containing a comfy chair, a collection of six heather brooms, and a rope into which crow, rook, and white goose feathers had been woven. This “witch’s ladder,” as it was identified by the workmen, was apparently used to work black magic, not to get from one place to another. In his book History of Wellington, A. L. Humphreys suggests it was used to cross from rooftop to rooftop, but surely that was what the brooms were for? Taking their cue from early Wiccan writers such as Gerald Gardner, modern Witches use the witches’ ladder, also known as a “wishing rope” or sewel, to work white magic. The last occupant of the house in Wellington was an old woman. How she was supposed to have gotten in and out of the hidden room where she kept her broomsticks we are not told.

38. “The Three Little Men in the Wood,” another of the Grimms’ fairy tales, was apparently never even in the running to become a seasonal opera, even though it opens in the snowbound forest. “The Three Little Men” features the almost universal “berries in winter” folktale motif as well as incorporating elements of Cinderella, Snow White, and Frau Holle, with the heroine taking on shades of White Lady toward the end of the tale. But, unlike “Hansel and Gretel,” “The Three Little Men” has neither a witch nor a Lebkuchen house, so I suppose there was really no contest.

39. In “The Three Little Men,” the wicked stepmother sends the unnamed heroine out in a paper frock to gather strawberries in the snow.