Reindeer Games

We know that Santa Claus took his name, if not his character, from the fourth-century St. Nicholas, Bishop of Myra in Asia Minor. His headquarters, therefore, really ought to be in Turkey, perhaps among the outbuildings of some crumbling mountain monastery. There, elves bearded and hooded like orthodox monks would whittle away by the light of the beeswax candles, all the while conversing quietly in New Testament Greek. Under the smudged gaze of the icons, they would keep themselves busy boxing up batches of Turkish delight to distribute to the world’s children. Or, Santa might have placed his enterprise further to the east, amid the snows of Mount Ararat, where the wrecked stalls of Noah’s ark would be put to good use again as workshops and warehouses. What better setting for the elves as they carve all those toy animals?

If I were to posit a third location for Santa’s workshop, it would have to be the federal state of Thuringia in east-central Germany. Das Wütende Heer, as the Wild Hunt was known in the snow-covered Thuringian forest, was led by a white-bearded gentleman named Eckhard. The Hörselberg, the magical mountain from which the procession issued, belonged to a goddess referred to in the thirteenth-century Tannhäuser legend as Venus, Roman goddess of love, but who might originally have been Freya, one of the Vanir, or Norse fertility gods. The errand on which Eckhard and his troop were bound was a trip around the world, an excursion that took them only five hours. Unfortunately, no sleigh is mentioned in relation to Eckhard, only a black horse and a staff. And since the Hörselberg, a.k.a. “Venusberg,” was the scene of fertility-inducing sexual license, the elves would probably have been making the wrong sort of toys.

Like St. Martin’s Land, Santa’s realm is necessarily one of the imagination, and for various reasons the Arctic serves as the most magical blueprint for this never-to-be-discovered country. But before we can explore the reasons why, we must explore a name. Lapland, which lies well within the frozen embrace of the Arctic Circle, is so called because it is the home of the Lapps, a non-Germanic Scandinavian people who have been there for as long as anyone can remember.23 Although they share certain aspects of their culture with the peoples of Siberia, their language is most closely related to Finnish. The term Lapp is so old that its etymology is uncertain. One theory is that “Lapp” meant “patch of cloth”: not such a strong indictment, especially given that it may simply refer to the use of appliqué in their traditional woolen garments. Then again, it may come from a Finnish word meaning “people who live at the edge of the world.” The Norwegians referred to them not as Lapps but as “Finns on skis.” Either way, the preferred term is now Sami,24 which is what the Sami have been calling themselves all along, so that is the term I will use.

When it comes to their homeland, I am going to stick with “Lapland,” because, at least for us non-Sami, “Lapland” says Christmas magic far better than the more-correct Sápmi. Lapland’s reputation as a magical place inhabited by a magical people probably goes all the way back to the first encounters between Norsemen and Sami. Even before the divisive advent of Christianity, the Sami differed from their Nordic neighbors both culturally and spiritually. While their southern neighbors were able to scratch out a few farms from the deciduous forests and the steep banks of the fjords, the Sami’s arctic environment dictated nomadism. The word tundra comes from Sami. During the blink-of-an-eye summer, the surface of the tundra turns into a spongy, insect-ridden bog. The rest of the year, it is covered in ice and snow. And while the mountains of Lapland are picturesque, they are impossible to farm. The only crop the Sami could depend on was lichen, the reindeer’s mainstay.

For the Sami, the spirits of the mountains and bogs were always close at hand. The Sami gods were visible in such naturally occurring idols as an oddly shaped boulder or birch snag, and they were audible through the medium of the reindeer-skin drum. In both the pagan and the early Christian eras, the Norsemen, whose native religion was shamanic to a somewhat lesser degree, often employed the Sami as consultants in times of supernatural need. With the help of the drum, the noide, or Sami shaman, allowed his spirit to fare forth from his body, enabling it to spy on people and find lost objects in places as far away as Iceland.

The Sami’s reputation as a magical people endured over distance and through time. The Norse sagas tell of children like Gunhild Asursdatter, who was sent away to learn witchcraft from two men of Finmark, one of the northernmost portions of Lapland. These men were such powerful sorcerers that they could kill with a glance.25 In Russia, Ivan the Terrible sent an envoy to the Sami to get their take on the recent appearance of a comet. It was believed that the Sami could also raise thunder and lightning and control the winds by the tying and untying of knots. In 1844, Andersen’s “The Snow Queen” featured a Wise-woman of Finmark who could “twist all the winds of the world into a rope.”

While the Catholic Church frowned upon such doings, it was the Lutherans, still caught up in the zeal of the Reformation, who really got the persecutions going. Suffice it to say that we are lucky to have any of the noide’s old drums left to look at. But the flame of magic, even the smoky rumor of magic, is a hard one to snuff out. No matter how thick a layer of ashes you kick over it, the fire always struggles back to life, though it may not burn the same color as before. The Sami retained their supernatural aura well into the nineteenth century—long enough to sell the jolly old elf eight head of tiny flying reindeer.

All of this is most likely unknown to the average letter-to-Santa-writer. Still, the old man’s arctic idyll persists. Perhaps it has something to do with Lapland itself. Most of us have witnessed snow’s power to transform an ordinary landscape into a white wonderland. Now add to this the lambent play of the aurora borealis, the “blue lights” that the Snow Queen burns in her palace each evening. Behind these blowing veils, the stars show crisp and clear, while the moon admires her reflection in the hard crust of the snow. And then there are the acoustic qualities of snow. Compare the steady jingle of a reindeer’s harness ringing out over the frozen tundra to the hollow clanging of a goat’s bell in the dry Turkish hills.

Whatever the source of Lapland’s magic, it’s too late for Santa to relocate. Following the lead of dear Virginia’s rule of thumb, “If you see it in the Sun, it’s so,” children’s program host Markus Rautio announced on Finnish radio in 1927 that Joulupukki, the Finnish Father Christmas, made his home on Lapland’s three-peaked Korvatunturi Fell. Because it straddles the border between Russia and Finland, the mountain is off-limits to the casual visitor. In this respect, English-language media has gone one better, convincing children that Santa’s workshop is planted squarely at the North Pole. Theoretically at least, one could get permission from the border patrol to climb Korvatunturi Fell, but the North Pole? I suspect that the “Santa lives in Lapland” theory has been actively suppressed in the United States because we don’t want our children getting wind of the fact that there is now a sort of Finnic Disney World near Lapland’s capital, Rovaniemi. There, you can meet Joulupukki himself, observe the elves at work, and ride in a sleigh drawn by reindeer, all for the price of a transatlantic plane ticket plus hotel.26

Stallo

Yule has never loomed particularly large on the Sami calendar. Their reluctance to celebrate the birth of Christ is reflected in the laws enacted in the eighteenth century requiring church attendance on December 24. Well into the twentieth century, the holiday, for many Sami, paled in comparison to Easter or St. Andrew’s Day (November 30). There were, however, special precautions to be taken on Christmas Eve. Sami parents warned their children to be on their best behavior as preparations were made for the arrival of a certain sleigh. Firewood was stacked neatly, so the sleigh’s runners would not snag on any out-sticking twigs, and a sturdy branch was staked by the river so the driver could tie up his vehicle and drink his fill of the cold water before moving on. Move on quickly was what the Sami were anxious for him to do, for this driver was not Santa but a wicked giant named Stallo.

Stallo resembles the troll of Swedish fairy tale, with a huge nose, tiny eyes, and knotted black hair. Some say he is as stupid as a troll, while in other accounts he has magical abilities comparable to those of the noide. Stallo is actually only half troll; the other half is human. This human half may link him to the early Samis’ conception of their non-Sami neighbors, or at least to their dead. The material culture of the Sami was founded on wood, skin, and bone, while Stallo was greedy for silver and gold. The ancient reindeer herders could not have failed to notice their more settled neighbors’ devotion to metallurgy, an apparently magical process, or the value they placed upon its incorruptible products. This is not to suggest that the Sami were naïve; within the mythologies of the metallurgists themselves, the smith is portrayed more as a magician or god than as an ordinary craftsman—the smith Ilmarinen of the Finnish epic Kalevala forged the lids of heaven, among other wonders, and the Anglo-Saxon Wayland the Smith bears the epithet “lord of the elves.”

Stallo continues to be associated with non-Sami graves and stone house foundations within Lapland: that is, with those places haunted by the ghosts of Norse or Finnish settlers. Perhaps a band of Sami had witnessed the laying in howe of some Bronze or early Iron Age warrior all clad in armor, his sword at his side. Before such a grave was eventually abandoned, they would have observed the leaving of offerings on the grave mound and concluded that the clanking ghost within must be propitiated or at the very least avoided. Stallo’s name may come from a word meaning “metal,” and he does love the stuff. In one story, he falls through a hole in the ice because his eyes are fixed upon the moon, which, he is convinced, is made of gold. In another, he is weighed down by a haul of silver, though it is usually children he lugs around in his sack.

The fact that Stallo prefers to cook children before he eats them usually gives them a chance to outwit the brute, make their escape, and count it as a lesson learned. Because he only snatches naughty children, he appears to be in the same class as Čert and Black Peter. While those two labor under the restraining influence of St. Nicholas, Stallo would not think twice about stuffing good girls and boys in his sack. But he can only ever get his hands on the bad ones. It is the children who disobey their parents—staying out too late is the most common offense—who find themselves en route to Stallo’s cauldron. Stallo, then, is a cautionary figure, and not all Stallo stories end happily.

It’s one thing to pretend you can’t hear your mother calling because you’re too busy trying out your new pair of skis in the moonlight, or to take your time coming home from your friend’s kota on a bright summer evening, but once upon a time there were some really horrible children in Lapland: three boys who refused to accompany their parents to church on Christmas Eve. Unlike the virtuous little red-socked children in “See My Grey Foot Dangle,” these boys are plotting mischief as soon as they shut the door behind their mother and father. Instead of staying safe inside the house27 as they were told, they venture outside to try their hands at slaughtering a reindeer.

Unfortunately, there are no reindeer to be found, so the youngest boy agrees to play the part of the sacrifice. He may have thought his brothers were only playing a game, but soon his blood stains the snow. The other two hack him to pieces and light the fire under the pot. As the meat cooks, the smell of human flesh draws Stallo from the forest. In an instant, he is upon the surviving brothers, his huge head and tangled hair blotting out the stars. The first boy is killed instantly, while the second escapes into the house and hides inside a chest. It is he who suffers the worst death of all, for Stallo kindles a fire inside the chest by blowing sparks through the keyhole and roasting the boy alive.

One expects such things from Stallo, but how to explain the boys’ own cannibalistic behavior? Well, just as Stallo is half-troll, it was rumored that some Sami might be half-Stallo, for the monster had a huge sexual appetite as well. In many of the tales he is either happily or unhappily married to a troll woman, but he prefers the pretty young Sami girls. In Finland, the Christmas processions of earlier centuries sometimes included a randy Stallo: a large youth dressed in ragged black clothing who tried to poke his wooden club up the girls’ skirts. (This may be the reason why so many Finnish girls now go about dressed as male or at least asexual tonttu at Christmastime.) So perhaps the boys were Stallo’s progeny.

Then again, maybe the boys weren’t really so bad after all. They may simply have been re-enacting a Christmas ritual they had seen their elders perform—with a real reindeer rather than a human child. Too young to understand what they were doing, though not to get the job done, they might have expected their little brother to be returned to them on the tide of the northern lights, which some Sami believe to be a manifestation of the ancestors.

The Yuletide People

It is not entirely clear who or what the Yuletide People were, though they appear to be part of the widespread northern tradition of honoring and feasting the dead at this time of year. We know that they were the recipients of sacrifice and that the air was thick with them on Christmas Eve. We do not know what they looked like or how much sympathy they might have had for humankind. What we do know comes from scenes painted on drums as well as from the complaints of seventeenth-century clergymen. At least one Protestant cleric referred to these Sami spirits as the Julheer, linking them, at least in the mind of the writer, with Das Wütende Heer and with the Jolorei, yet another name for the Norse Yule Host or Wild Hunt. But it was a German theologian’s Juhlavolker, translated poetically into English as “Yuletide People,”28 that has stuck.29

Try as they might to get the Sami to Mass, those harried clergymen could not prevent some of their parishioners from slipping outside to attend older spirits, for the Sami gods were not to be found inside a church. One of the ceremonies involved removing all but the trunk and central boughs of what would today be a modest-sized Christmas tree. A reindeer was then slaughtered and the tree painted with its blood. Select portions of the sacrifice, including the lips, were draped over the branches and consecrated to the Yuletide People.

In yet another ritual, the participants fasted, collecting morsels of their Christmas Eve feast in a boat-shaped birch-bark basket painted red, again with reindeer blood, and sealed with melted fat. The basket was then hung from a tree in the forest, too high up for wolves or naughty children to pull down. Only after this spiritual Christmas hamper had been delivered could the mortals return home to their own festivities.

I do not know if it is possible to draw the Yuletide People into your own observance without blood, molten fat, and fresh reindeer lips, but you can certainly try. Pack a basket full of Christmas goodies and consecrate it to the Yuletide People but donate it to the living. You can also take note of the role of the seite in ancient Sami religion. A seite is an unusually shaped feature of the landscape such as a rock or a tree stump. A carving knife was sometimes used to tease out a figure that nature had already suggested, but for the most part a seite is found, not made. The seite was deemed worthy of sacrifice, and not all sacrifices were bloody. Although the gods did occasionally call out through the drum for the gift of a horse or a reindeer, bones, coins, and all manner of trinkets could also be offered to the seite.

On, Prancer!

Thanks to the names given them by Clement Moore, not to mention the work of Arthur Rankin and Jules Bass, we tend to think of the eight tiny reindeer pulling Santa’s sleigh as males, but the females of Rangifer tarandus also sport modest antlers with which they protect their calves from potential predators. Reindeer calves are conceived in September and born in May, so the does are already a few months gone by Christmas Eve. I doubt Santa would want to endanger the health of a gestating female by asking her to pull a fully loaded sleigh around the globe, so Dasher, Dancer, and all the rest are probably males.

They cannot, however, be bulls, for all that autumnal rutting has left the mature, sexually potent males too weak to pull the sleigh. The exhaustion following the frenzy of courtship shows itself in the bulls’ antlers, which by early winter have begun to drop off. And when did you ever see one of Santa’s reindeer with only half a rack?

There is only one kind of reindeer suitable for pulling Santa’s sleigh and that is the harke, or castrated male. The harke, whose testicles were traditionally bitten off by the herdsman, is real Christmas-card material. With few demands on his energy, he is able to keep his fine antlers as well as a thick coat and enough body fat to keep him going on his world tour. A harke in harness looks very festive indeed, for the old-time reindeer harness is an elaborate affair, the leather collar adorned with appliqué, couched tin thread, and a variety of bells.

The Witch’s Drum

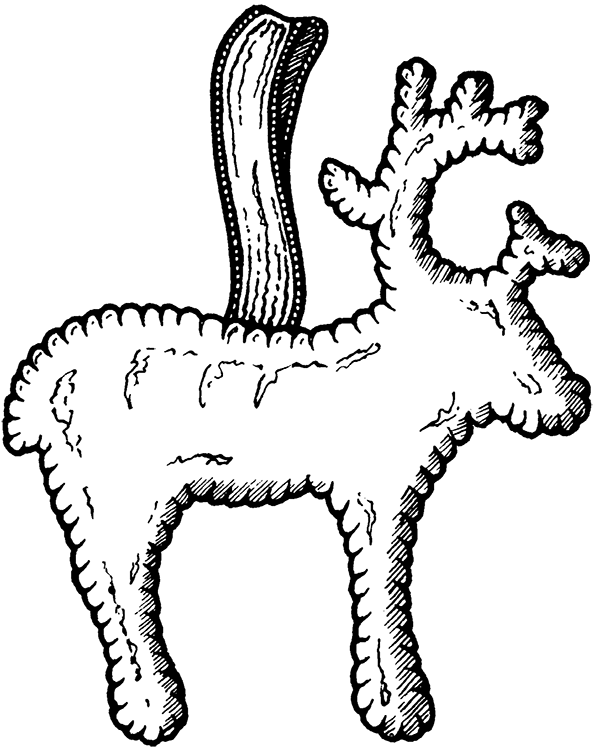

Compared to the harke in full regalia, the reindeer in the following craft is a bit of a Plain Jim. That’s because he was inspired by the many reindeer one can see painted on the Sami shaman’s drum, sometimes known as a “magic drum” or even a “witch’s drum.” As large as a small child and roughly oval in shape, the skin of the drum was smoked to a snowy whiteness, then painted all over with figures drawn in the artist’s saliva, which was made red by the chewing of alder bark. There are anthropomorphic figures, mountains, bodies of water, birds, and animals, but most of all reindeer. The edge of the drum was hung with amulets made from fur, hooves, and bone.

One of the purposes of this drum was to divine the future. When the noide had entered his trance, he placed an arpa, a triangular piece of metal or bone (not unlike the planchette from a Ouija board), upon the drum skin. Then he struck the drum with a stick shaped like a Thor’s hammer. The arpa would then jump about from picture to picture, giving the drummer an idea of what to expect in the coming season. Sometimes, the gods spoke through the drum to request a sacrifice.

We hear quite a bit about these “witches’ drums” in the Norse sagas and again in the seventeenth century when Protestant proselytizers took an interest in burning them. Since they were made of organic material, it’s impossible to say how long such painted drums had been in use, but Stone Age pictures of reindeer similar to those seen on the drums have been found in red ochre on sheltered rock faces throughout Lapland.

Craft: Sacrificial Reindeer Ornament

Craft: Sacrificial Reindeer Ornament

For this craft, I have suggested a red ribbon in token of the blood that was offered to the Yuletide People in ancient days, but it need not be a plain red ribbon. The Sami are famous for their brightly colored tablet-woven bands that often incorporate metallic thread, so don’t be afraid to be festive.

Tools and materials:

2 squares white felt

Clear tape

Scissors

Needle and white thread

5 or 6 cotton balls

Toothpick

¼-inch-wide red cloth ribbon, about 6 inches long

For easier stuffing and sewing, I suggest photocopying the template (figure 7.1) at 129 percent. Trace and cut out your template, then stick it to your felt with a generous number of clear tape strips. This beats tracing the image onto the felt, which is more work and would leave pen marks on your finished product.

Cut out the antlers first, since they are the most intricate. When you have cut out two reindeer this way, lay them one atop the other, making sure all the details line up, and whip-stitch them together. Stitch the antlers first.

Sacrificial reindeer ornament, figure 7.1

Stuff the figure with wisps of cotton ball as you go. Use a toothpick to help push the stuffing in. The points of the antlers will be too skinny to stuff.

Don’t forget to add the ribbon. Fold it in half and insert it in the reindeer’s back and whip-stitch right through it.

Hang your finished reindeer on your Christmas tree or one dedicated to the Yuletide People.

Sacrificial reindeer ornament

The Horns of Abbots Bromley

Until about 1660, reindeer were an integral part of the Christmas season in the Staffordshire village of Abbots Bromley. Since then, the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance has been held in early September, but in the late sixteenth century it was performed at New Year’s and Epiphany. At that time, and possibly earlier, the six pairs of antlers were set in carved wooden heads—three painted red, three white: the heraldic colors of the village’s most prominent families. The colors have since changed, but, when not in use, the antlers are still kept in St. Nicholas Church.

The dance takes place outside hallowed ground. The Deer Men, as they are called, are not the only participants in this dance, but they are certainly the main attraction. They do not actually wear the antlers, but hold the sticks with the wooden heads at chest level while supporting the weight of the antlers on their shoulders. In The Lost Gods of England, Brian Branston relates the Horn Dance to an incident in 1255 in which a company of thirteen cheeky poachers mounted a stag’s head on a pole in the middle of Rockingham Forest in apparent mockery of the king. Branston goes on to ask the reader if it is too much to believe that in both cases the participants were acting as shamans in a once-widespread prehistoric tradition. The fact that the Abbots Bromley horns are reindeer antlers would suggest that it is not, since reindeer have been extinct in England for thousands of years. Unfortunately for Branston, the antlers were not actually handed down from the Age of the Cave Painters. They are, however, quite old, having been carbon-dated to the eleventh century, at which time they belonged to six castrated males—exactly the kind of reindeer that might be expected to pull Santa’s sleigh. Even if one were to dispute the dating, England’s Ice Age hunters never domesticated the reindeer and therefore would not have been in a position to castrate any of them.

The Abbots Bromley antlers must have been acquired through trade or as part of some unusual dowry. Most likely, Staffordshire was not their first stop on their way down from Lapland. Had they still been attached to the skulls, they might very well have ended up in some hunting lodge in Needwood Forest, but free-floating reindeer antlers have little commercial value unless one plans to carve them into combs, buttons, or cup handles. Whoever installed them at Abbots Bromley would have been a connoisseur of the unusual, or he was in his cups when he bought them. I would not be at all surprised if they had been won in a card game.

Another theory goes that they were brought to town by a settler from Norway. White and red are, after all, the traditional Scandinavian Yule colors. Is it too much to believe that the same settler commissioned the first seasonal Horn Dance to remind him of his homeland? No doubt it is. Nowadays, the heads are painted white and brown, not because there are no more Norwegians in the village but because those prominent families of the sixteenth century have dwindled into oblivion.

The earliest written record of the horns’ appearance in what was then known as the Abbots Bromley Hobby-horse Dance dates to around 1630. The dance itself was already mentioned in 1532, but we cannot be sure the horns were part of it. As elsewhere in England, a hobby-horse remains the central figure in the dance, though most people now come to see the horns. And that is exactly why the Abbots Bromley dancers would have incorporated them into their ritual in the first place: because they had them, and the other Midlands villages did not. The purpose of the performance is clearly described in the account from the seventeenth century: to solicit monetary donations that went to spruce up the church and provide cakes and ale for the poor.

Happily, these details meant little to the folklorists who first poked their noses and their pens into the histories of such village traditions. To them, as to the later Branston, the horns and the dancers in their gaily patterned breeches were relics of Europe’s long shamanic winter. Such a captivating idea is hard to dispel. Eric Maple, writing in 1977, a full twenty years after Branston, refers to the Horn Dance as “Another survival from ancient times.”30 Maple, who regards the performance as a fertility rite, reckons that the Deer Men’s overriding mission is to carry blessings to the fields.

In the end, whoever hauled the six pairs of antlers into town all those centuries ago should now be hailed as a hero, for while hundreds of other hobby-horse dances have bitten the dust, the Horn Dance is still going strong. And though they probably weren’t expecting it, it appears that the good citizens of Abbots Bromley have received a lasting gift from the Yuletide People.

23. Because of their stature, smaller than that of their Russian or Germanic neighbors, and because of their supposedly peculiar cranial measurements—early-twentieth-century anthropologists were wild for cranial measurements—the Lapps, like Gardner’s pixyish Picts, have also been put forward as the original elves.

24. You will also find it spelled “Same” and “Saami.”

25. Gunhild eventually becomes a witch in her own right, but she repays her teachers very poorly. She charms them to sleep and cinches them up in sealskin bags into which she invites King Harald Hairfair’s men to thrust their weapons.

26. If you’re not up for this kind of adventure, you can put your kids off the scent by showing them the Finnish film Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale, which builds on the Korvatunturi Fell theory but features a Joulupukki they won’t ever want to meet.

27. Even those Sami who are still nomadic maintain villages of permanent houses where they spend much of the winter.

28. The furthest back that I have been able to trace the English term Yuletide People is 1954, when it is offered as translation

of both joulu-herrar and joulu-gadze. It appears in the essay “The Lapps and Their Christmas,” by Ernst Manker in the book Swedish Christmas. On the book’s copyright page, translations are attributed to “Mrs. Yvonne Aboav-Elmquist, M. A. Oxford, and others.”

29. “Stuck where?” you might ask if you are hearing the term for the first time. Surprisingly enough, the subject of the Yuletide People was a popular seasonal filler in smaller American newspapers of the 1970s.

30. See Eric Maple, Supernatural England, pages 41–42. While Maple’s telegrammatic style can be a time-saver, I recommend Ronald Hutton’s The Stations of the Sun, pages 90–91, for a more sober treatment of the subject.