ROGER ANGELL TRAVELED TO PITTSBURGH IN 1970 to cover the Pirates’ playoff series with the Cincinnati Reds. Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium had opened earlier that year, and after a “study” of the new stadium, Angell wondered “how ballplayers nowadays can remember which town they are playing in as they look up at the same tiered, brightly painted circles of seats that, rising above fields of fake grass, identically and anonymously surround them in so many big-league cities.” Three Rivers, home to both baseball’s Pirates and football’s Steelers, was yet another in a wave of new multipurpose stadiums built in the mold of Busch Stadium, D.C. Stadium, and Atlanta Stadium—each circular, enclosed on all sides by banks of seats. “More and more these stadia remind one of motels or airports in their perfect and dreary usefulness,” Angell observed. “They are no longer parks but machines for sports.”1

As Angell suggested, many big-league cities owned, or had plans to build, a “machine for sport” by 1970. New stadiums were modeled on structures like Shea Stadium, the Astrodome, and Busch Stadium, buildings that had been admired for their sense of novelty and ambition. And yet by 1970, stadiums that appeared futuristic and forward-looking just years before now increasingly seemed, ironically, behind the times. Many boosters and reporters continued to celebrate new stadiums as expressions of modern progress. But for a growing number of people, each new stadium represented another step in the dour march of modernist standardization, replicating the same spaces and sports experiences in city after city—derivative concrete cylinders dropped into lots swept clean by urban renewal, outfitted with artificial turf, squawking scoreboards, and private restaurants and luxury suites. Many of the tenets of postwar modernism—rationalism, symmetry, monumental-ism, an abiding faith in new technologies, and a blind belief that all of these things signified “progress”—seemed increasingly out of step with the times, as more Americans were concerned with ecological integrity, historical roots, and authenticity.

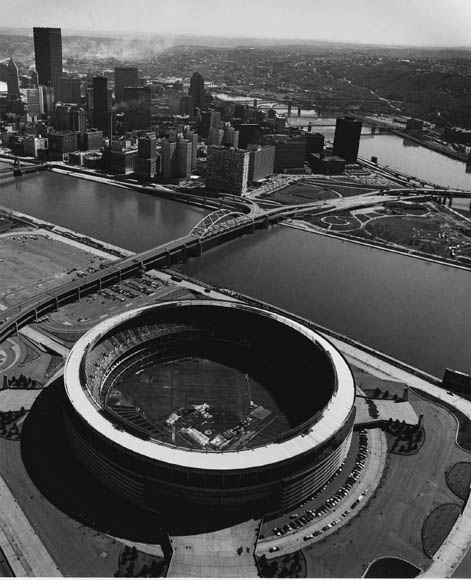

FIGURE 68. The modernist Three Rivers Stadium—Pittsburgh’s “machine for sport”—opened in 1970. Its circularity helped it convert between baseball and football formats, to host both the Pirates and Steelers. But this circularity also pushed fans for each sport farther from the field than had the Pirates’ Forbes Field and the oval Pitt Stadium, the Steelers’ home for the previous decade. ALLEGHENY CONFERENCE ON COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PHOTOGRAPHS, MSP 285, DETRE LIBRARY & ARCHIVES, HEINZ HISTORY CENTER, PITTSBURGH.

A dreary placelessness born of modern standardization wasn’t the only thing Angell noticed when he first visited Three Rivers Stadium in 1970. He was also struck by the “immense glassed-in dining room and bar called the Allegheny Club” that broke up the monotonous concrete cylinder of plastic seats. This private club lorded high over first base on the third and fourth tiers of the stadium, a fortress “permitting affluent locals (who may also lease private boxes, at a price of $38,000 for five years) to take their baseball a la carte.”2 There were forty-two pricey private boxes ringing the stadium. In Pittsburgh’s new, publicly funded, $55 million stadium, the well-to-do and socially connected could assemble, screening themselves out of the stadium public, and take their sport in small doses—a sports-themed buffet item among other diversions.

FIGURE 69. The Pirates’ old ballpark, the irregularly shaped Forbes Field (opened in 1909), is in the foreground, adjacent to the University of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning. The Steelers played at Forbes from 1933 until 1963, though in 1958 they began playing some games in the classic football bowl of Pitt Stadium (opened in 1925), seen here in the center of the image. They played all their games at Pitt Stadium between 1964 and the opening of Three Rivers in 1970. Downtown Pittsburgh is visible in the distance. The future location of Three Rivers Stadium was directly to the right of downtown, across the Ohio River. AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHS OF PITTSBURGH COLLECTION, C. 1923–1937, AIS.1988.06, ARCHIVES SERVICE CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH.

Characteristically perceptive, Angell’s portrait identifies the state of the stadium in 1970 and also anticipates the shape of things to come. The era of postwar modernist stadium building—envisioned by Geddes beginning in the late 1940s, enabled by the Braves’ move to a new County Stadium in Milwaukee in 1953, and fully launched with the concrete style of Candlestick Park in 1959 and the multipurpose functionality of the District of Columbia Stadium in 1961—had run its course with the opening of Minneapolis’s Metrodome in 1982. Stadium planning and design moves in cycles, and the next wave of stadium building exploded in the early 1990s. Those postmodern stadiums—initially and most famously Baltimore’s Oriole Park at Camden Yards—demonstrably rejected the placeless, cookie-cutter modernism of the previous decades, celebrating above all else a sense of place. But snuggled into the new designs were even more private clubs and suites at a scale that would make Three Rivers look communistic, as well as an ethic of sports “à la carte” that has come to define the stadium “mallpark” experience.3

The Pirates called Three Rivers Stadium home for just three decades—half the time they had played at their previous ballpark, Forbes Field. Their new baseball-specific facility, PNC Park, was opened a few hundred feet east of Three Rivers in 2001. It was one in a wave of “retro” ballparks that had been built in or near downtowns over the previous decade, beginning with Baltimore’s Camden Yards in 1992.4 These were facilities designed as throwbacks to a previous era—that of the now-deemed “classic” ballparks like Forbes Field. The NFL’s Steelers, former roommates of the Pirates at Three Rivers, got a new football stadium of their own, Heinz Field, directly west of its predecessor. Like the new baseball park, this open-ended horseshoe’s signature quality was its enthusiastic expression of place. Both new stadiums looked directly across the Ohio River to the city’s “Golden Triangle,” a corporate spectacle of soaring glass skyscrapers. Fans and players weren’t trapped in an anonymous web of plastic seats like their counterparts in Cincinnati, St. Louis, Atlanta, and Philadelphia—this was Pittsburgh.

The modern stadium had been split in two. No longer would fans have to endure the circular and plastic utility of the multipurpose stadium, which in accommodating both the rectangular gridiron of football and baseball’s diamond complemented neither all that well. The anonymous cylinder was broken apart to reveal the world outside. Steel, brick, and limestone—the materials of prewar stadiums and ballparks like Ebbets Field, the Polo Grounds, and Pittsburgh’s own Forbes Field—replaced smooth concrete walls and columns. On the face of it, this seemed the revival of an era of more democratic stadiums from a seemingly more authentic era of sport—a real revolution in stadium design.

FIGURE 70. The private, glassed-in Allegheny Club hovers over the scene as Steelers running back Franco Harris charges toward the end zone. AP PHOTO/NFL PHOTOS.

But the rediscovery of the local, the intimate, and the seemingly authentic accompanied—and even masked—countervailing developments in stadium design. As architects, politicians, reporters, and fans celebrated the return of stadiums that seemed idiosyncratic expressions of local communities, they overlooked the ways new stadiums replicated and amplified many of the traits of their modernist predecessors. The private luxury suites and stadium clubs that Angell had pointed out in Three Rivers metastasized in the postmodern stadium. So too did an ethic of sport “à la carte,” through which the game on the field became simply a thematic anchor to a broader consumption experience, marked by souvenir shops, restaurants, bars, art installations, and sports-themed museums and memorials. The stadium experience burst with sensory stimulation—every moment filled with distractions competing with the game on the field, from advertisements and cheerleaders to video-board action and wireless connectivity. These were stadiums built not for fans but consumers—designed not to meet existing needs but to create and satisfy new ones. In the postmodern stadium, the aesthetics and rhetoric of democratic inclusion and traditionalism ran aground the realities of increasing economic inequality and consumerist spectacle. New stadiums certainly didn’t look like modernist machines for sport, but they had learned plenty from their predecessors. Technologies of exclusion, segmentation, and distraction define the contemporary stadium—all legacies of the modernist machines.

The modernization of stadium space since World War II converted the idiosyncratic urban ballpark into a placeless machine. Professional sports had been ripped from old neighborhoods and implanted in modernist cylinders—what sportswriter George Vass referred to in 1967 as “superficially attractive yet ‘soulless’ heaps of steel and concrete” that were being “stamped out” as if “with a cookie cutter” across the country.5 This term—“cookie cutter”—would become a standard pejorative for a whole generation of stadiums, not all of which exactly fit the bill. At the time of Vass’s writing, multipurpose and roughly circular modern stadiums had been built in the District of Columbia (opened in 1961), Queens (1964), Houston (1965), Atlanta (1965), St. Louis (1966), Oakland (1966), Anaheim (1966), and San Diego (1967). In truth, this was a more distinctive group of structures than it might have seemed—some with unique rooflines, some with openings in the seating bowl that allowed visitors’ eyes to wander outside. And yet, with the opening of Three Rivers Stadium and Riverfront Stadium—Angell’s “machines for sports”—there was a clear sense that each new stadium was less an adventure in modernism than a dutiful routine of concrete and plastic enclosure. Philadelphia’s Veterans Stadium debuted the following year. San Francisco’s open-ended Candlestick Park—the first major league stadium to adopt fully the engineered concrete idiom—was enclosed prior to the 1971 season to accommodate the NFL’s 49ers.6 This was followed by a string of urban domes in New Orleans (1975), Seattle (1976), Montreal (1976), Minneapolis (1982), and Toronto (1989). These were the apotheosis of the modern form—man the engineer, it seemed, had pacified unruly nature; the total obliteration of context was the price paid for this victory.

Stadium architect James Finch explained the trending routinization of the stadium form in 1971: “The current rash of stadiums is typical of the cycles architecture goes through. They are generated by developers; what goes well in one place is assumed to go well in another.”7 Expertise was spread from project to project and, unsurprisingly, stadiums increasingly resembled one another. Emil Praeger worked with Norman Bel Geddes on the stadium published in Collier’s in 1952 and designed Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. His firm, Praeger-Kavanagh-Waterbury, designed Shea Stadium and worked on the modernization of Yankee Stadium (completed in 1976). The firm teamed with two others on the Seattle Kingdome (1976), and consulted on the District of Columbia Stadium (1961) and the Astrodome (1965). The Osborn Engineering Company designed the District of Columbia Stadium and worked with two Pittsburgh firms on Three Rivers Stadium (1970). Osborn’s project manager at D.C. Stadium, Noble Herzog, designed Anaheim Stadium (1966). Atlanta Stadium (1966), Riverfront Stadium (1970), and Buffalo’s Rich Stadium (1973) were designed by the Atlanta firm Finch and Heery. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill produced the Oakland-Alameda County Stadium (1966) and the Minneapolis Metrodome (1982). Kivett and Myers designed Kansas City’s Arrowhead Stadium (1972) and Royals Stadium (1973), and also worked on New Jersey’s Meadowlands complex (1976). The contractor for D.C. Stadium and Philadelphia’s Veterans Stadium (1971) was McCloskey & Company. Huber, Hunt & Nichols, Inc., was the contractor for Riverfront Stadium, Three Rivers Stadium, and the Louisiana Superdome (1975). With such cross-pollination, it is no wonder that stadiums increasingly resembled one another.

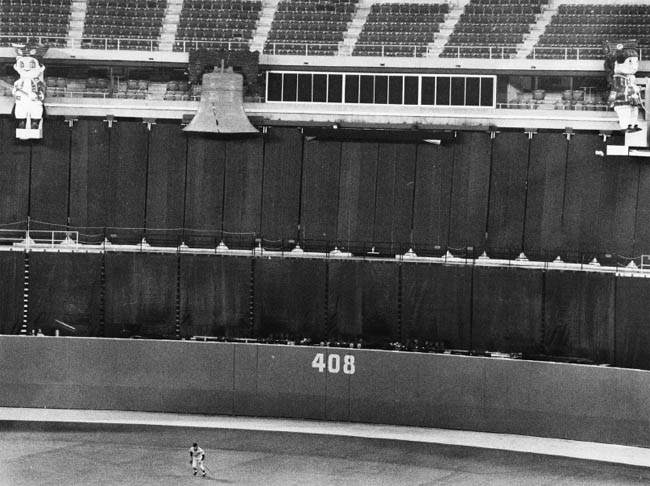

The monotonous regularity of the stands was echoed in the overwhelming symmetry of baseball’s outfield dimensions. In the older parks, of course, the layouts were all different, making game play different in each venue. However, in the modern stadiums built between 1962 and 1973, all baseball fields had even outfield dimensions, with center-field distances between 400 and 414 feet, and foul-pole distances between 329 and 338 feet.8 Thus almost every ballpark played the same. Though the football gridiron had long been standard from stadium to stadium, its layout within old stadiums was not, as it was wedged into parks designed for baseball and flanked by temporary banks of stands. This made for a variety of vistas, depending on the seat of the fan. The modern stadium removed the idiosyncrasies of play in baseball and perspective in football, regularizing a view of fellow fans, far afield in cantilevered decks.

The idiosyncrasies of the playing surface—at least theoretically—had been removed as well. The idea of using artificial grass in a stadium was nothing new; Norman Bel Geddes had pitched it for his proposed indoor stadium for Brooklyn in the early 1950s.9 The Astrodome was the first major stadium to put it to use, installing it during the 1966 baseball season.10 The original playing surface there was a lab-designed grass hybrid that could grow under the dome’s translucent Lucite panels. It was soon apparent that during day games the panels amplified daylight rather than diffused it, making it nearly impossible to see baseballs hit with a high trajectory. The Houston Sports Association responded to the problem short-term by painting over the panels. This, of course, killed the natural grass inside. The rest of that season was played on dead grass. A new artificial playing surface—designed by Chemstrand, a division of Monsanto Chemical Company—was installed in 1966.11

The artificiality of the grass marked a symbolic final severance with the natural world in the dome. For Roy Hofheinz, it was just another reason to celebrate: “Everything about the Astrodome is unparalleled and trail-blazing,” he boasted. Artificial turf “not only enhances our own facilities here,” he predicted, “but should also launch a new and wondrous era in recreational engineering. The Astrodome is honored to be the original site of this extraordinary experiment.” Manager Grady Hatton claimed that the new surface was a victory for fairness and predictability, ensuring the meritocratic nature of sport. He told stadium visitors, “This puts the icing on the cake. The Astrodome now becomes a real Utopia for baseball. No wind, no sun, no rain, no heat, no cold, and now no bad bounces.”12 Echoing the praise of modern stadiums more generally, advocates saw artificial turf as a symbol of progress. Richard Nixon, a visitor to the 1970 All-Star Game in Cincinnati’s new Riverfront Stadium, predicted, “AstroTurf is the playing field of the future.”13

FIGURE 71. The Astrodome installed AstroTurf in 1966, after the Lucite panels in the roof were painted over. The zippered seams of each section are visible in this photo. MSS 0157-0062, HOUSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY, HOUSTON METROPOLITAN RESEARCH CENTER.

Indeed it was, as every one of the stadiums constructed in the 1970s had artificial turf. It was installed in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Irving, Kansas City, New Jersey, Seattle, Minneapolis, Foxborough, and Buffalo. St. Louis, San Francisco, and Miami’s old Orange Bowl replaced natural turf with synthetics in 1970. The financial bottom line, unsurprisingly, drove this trend. Surfaces like AstroTurf or Tartan Turf, its main competitor, were relatively expensive up front, requiring about two hundred thousand dollars for a football field.14 However, after this initial investment, the field was much more durable and thus cheaper to maintain. Artificial fields could be used more frequently than delicate grass surfaces—an advantage for multipurpose stadiums hosting not only football and baseball but mass revivals, music concerts, and circuses. During the construction of Three Rivers Stadium, the Pittsburgh Pirates boasted of the many advantages of synthetic grass over the real thing. The new Tartan Turf field would provide “increased functionality” because it could be quickly adapted to other events; it would produce a “uniformity of the playing surface” that would allow for more consistent footing, more consistent ball bounces, and the “possibility of fewer ankle and knee injuries”; it would cut down on postponements “because water could be drained more quickly”; it would eliminate “muddy and otherwise undesirable field conditions that tend to detract from the superior performance of professional teams”; and, finally, it would “improve aesthetic appearance.”15 This litany of dubious justifications didn’t include the true motivating factor: artificial surfaces cost less in the long run.

Synthetic grass seemed a logical step in the modernization of sports spaces—a process that eliminated oddities and idiosyncrasies in the name of multipurpose functionality and the economic bottom line. Sports Illustrated’s William Johnson mused in 1969, “Perhaps it was inevitable in this, the Synthetic Century . . . in an age when people quite readily embrace plastic wedding bouquets and electric campfires and spray-on suntans.” Even yet, it was “still a shock” for Johnson to see football played on a “grassless gridiron, lush as a rug and flawless as a hotel lobby.”16

It was inevitable, perhaps—but not always welcomed. “Grass, the old-fashioned, common, green growing stuff, is dying out,” Peter Carry, also of Sports Illustrated, wrote in 1970. It was “a lamentable death wrought of ambiguity and polyester progress.”17 He noted that the cost savings might impress club owners and city councils, but most everyone else lost out. Though some baseball fielders claimed the turf produced more predicable bounces, Carry found that most players opposed this form of “progress.” Unlike natural grass surface, which absorbed heat, the asphalt foundations reflected it, yielding extreme field temperatures. Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium reported temperatures of up to 160 degrees on the surface; on a 90-degree day in Busch Stadium, it was 114 degrees six feet above the field. In some cases, such temperatures could cause blisters, melt shoe bottoms, and even lead to heatstroke. The asphalt base was also unforgiving to players’ joints. Though early on many advocates claimed that the fields would cut down on injuries because of their uniformity—beliefs encouraged by research presented by its manufacturers—independent studies increasingly showed that the synthetic grass was responsible for all sorts of physical problems. Cleats got caught in the turf, resulting in ligament and knee injuries. The underlying asphalt surface resulted in more head injuries. Friction burns and blisters became common as well.18

But it was baseball fans, Carry claimed, who were the real losers in new stadiums defined by “even bounces and inorganic sterility.” While the violence wrought by synthetic turf in some ways matched the violence of football, baseball’s “lasting attraction must be its atmosphere of relaxation and naturalness.” For evidence, he pointed to the young, friendly crowds at those traditional baseball-first, natural-grass ballparks, Boston’s Fenway Park and Chicago’s Wrigley Field. There, he wrote, “the atmosphere is warm, unhurried, occasionally exciting and generally very healthy.”19 But while artificial turf could influence the feel and pace of the stadium—rendering it cold, rushed, and unhealthy, as Carry suggested—new electronic technologies would more radically reshape the traditional stadium experience, dominating the eyes and ears of ballpark visitors.

At the end of the 1950s, a scoreboard was largely what it sounded like—a vertical board where scores were posted, likely accented with an advertisement for a regional brewer. Scoreboards of the 1960s, like those at Shea Stadium and the Astrodome, increasingly played a more invasive role in the stadium experience. By the mid-1970s, scoreboards were hosting video screens that commanded the attention of visitors nearly as much as the game on the field. The development of the scoreboard—from a silent and functional tool to a multimedia competitor to the main event—was incremental and uneven from stadium to stadium. Enhanced scoreboards produced exploding spectacles of light shows and fireworks. They entreated fans to cheer. They trotted out rudimentary animations. Such features indeed drew fans’ eyes and encouraged a more systematic and directed involvement in the game below. But with more sophisticated video-board technologies, evident in the opening of the Louisiana Superdome in 1975, the scoreboard increasingly became an outsized television—a screen that replicated the viewing experience from home. Accordingly, the ways the games were produced—on television and in the stadium—converged as well.

Ironically, the inspiration for the modern scoreboard was installed in one of baseball’s oldest grounds, Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Unsurprisingly, it was the brainchild of one of the game’s most notorious promoters over the previous two decades: Bill Veeck. Veeck, who had worked his way back into the major leagues as a part owner of the White Sox in 1959, introduced his famous exploding scoreboard in 1960. The elaborate pinball machine in William Saroyan’s play The Time of Your Life provided the model. When a player hit the jackpot, Veeck remembered, “the machine practically exploded. The American flag was unfurled; battleships fired guns; music blared. It was just so silly, you know, that it was unforgettably funny. I began to imagine something like that on a big scale, like a scoreboard.”20 Veeck’s new scoreboard, nicknamed “the Monster” and “the Thing,” cost three hundred thousand dollars. It soared above Comiskey’s center-field bleachers, topping out 130 feet from the ground. Slender columns rose above the board, loaded with fireworks, set to go off upon a White Sox home run. When the scoreboard exploded, one reporter wrote, “Lights flash, sirens scream, whistles blow, fireworks light up the sky and aerial bombs shake the ball park as the slugging hero trots around the bases.”21 Veeck’s invention was the first in a stadium scoreboard arms race that would quickly escalate.

Electronic messaging was one of the first features of the modern scoreboard; it debuted at Yankee Stadium in 1959 and was built into the District of Columbia Stadium in 1961.22 Dodger Stadium, opened in 1962, employed two message boards above the outfield pavilions. One delivered lineups, scores by inning, and game statistics. The other gave results from other games, announced attendance figures, made special announcements, greeted visiting groups of fans, and delivered crowd instructions.23 Such computer-controlled messaging might seem quaint today, but the impact then was considerable, commanding the attention of spectators and dictating their responses to the game. Roger Angell observed the influence of the “huge, hexagonal sign” on Los Angeles crowds in October 1962. “The fans respond to its instructions with alacrity,” he noted, “whether they are invited to sing ‘Baby Face’ between innings or ordered to shout the Dodger battle cry of ‘CHARGE!’ during a rally.”24

Each new stadium boasted a new scoreboard that attempted to outdo the last one; it was “the new status symbol,” as a reporter visiting new Shea Stadium claimed in 1964.25 Shea’s freestanding Stadiarama Scoreboard, with its eighteen-by-twenty-four-foot rear projection screen Photorama video board, was taken down a peg by the Astrodome’s two-million-dollar scoreboard, 474 feet long and four stories high. The Astrodome set a standard that was difficult for most to match, though this didn’t stop the lips of local boosters who claimed to surpass it with each new stadium. John Hall, a columnist for the Los Angeles Times, told readers that while fans in Anaheim weren’t going to get a dome when the new stadium opened in 1966, they wouldn’t “have to take a rumble seat to Houston in the scoreboard department.”26 The nickname of Anaheim Stadium, “The Big A,” actually derived from its scoreboard: a 230-foot A-frame scoreboard sited just beyond the left-field wall, topped with a revolving halo. Hall joked that future astronauts might mistake the halo for a ring of Saturn, adding vaguely, “Progress is wonderful,” as if this towering board was evidence of the peak of human accomplishment.27 A writer for the Sporting News branded it “the world’s largest teleprompter” and “electronic cheerleader”; it seemingly relieved fans of the burden of deliberation, telling them precisely when to shout “Charge!”28 Scoreboards in other new stadiums in Oakland, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati struggled to keep up, though their promoters assured local fans that their new scoreboards were cutting-edge.29

The exploding scoreboard at Philadelphia’s Veterans Stadium, opened in 1971, was particularly notorious. Baseball’s Phillies claimed their new scoreboard to be “the most expensive, largest and most sophisticated scoreboard in the history of sports.”30 Costing three million dollars—a figure the club advertised with pride—it was a “magic lantern of incandescence, images, and information; flashing forth with statistics, scores, rulings, group names, ticket information, coming events, and enhancing every game with caricatures, cartoons, commentary, and even commercials to help pay for itself.”31 It had, according to local sports writers, “the color and excitement of Disneyland.”32 The main attraction of the Magic Scoreboard was the home run spectacular. The Phillies noted some of the more memorable home run celebrations around the league—particularly the “war dance” in Atlanta after a Braves home run and the “cattle stampedes when an Astro puts one in orbit” in Houston. “But nowhere in the history of baseball,” promoters promised, “can one find a greater Homerun Spectacular than right here in Veterans Stadium.” The Phillies’ celebration featured two fifteen-foot-tall fiberglass animatrons, Philadelphia Phil and sibling Philadelphia Phillis, a fifteen-foot-tall replica of the Liberty Bell, a cannon, and water fountains. It was the stadium version of a Rube Goldberg machine; its elaborate mechanical display began with animatron Phil whacking a ball off the Liberty Bell, cracking it in the process. The caroming ball then hit Phillis “in the fanny,” as Phillies executive Bill Giles described it; as she fell down, she accidentally pulled a lanyard to an exploding cannon. A revolutionary-era American flag subsequently unfurled, water spurted from an outfield fountain, and the sound system blasted “Stars and Stripes Forever.”33 This chaotic scene was enough to impress many visitors. Maury Allen of the New York Post, mesmerized by the display, claimed, “No more bad jokes about Philadelphia. Any town that can build a $45 million ball park, featuring a $3 million scoreboard with Philadelphia Phil, Philadelphia Phillis, the Liberty Bell, a Revolutionary War cannon and Betsy Ross’ original flag . . . can’t be all bad.”34 The routine failed to properly come off in the stadium’s early days, prompting visiting sportswriter Roy Blount Jr. to remark, “Phillis struck a warranted blow for Women’s Liberation by declining to fall down.” When he asked Phillies manager Gene Mauch how he felt about “baseball’s greater and greater reliance upon such gimmickry,” a cowed Mauch replied, “It’s here.”35

Animatronic gimmickry did not become the norm, but it expressed widespread and profound changes in the production of the stadium experience. Filling the traditional pauses in game action with electronic content reworked the relationship between fans and the game, and thus the expectations and behavior of the crowd. Following his introduction to the Astrodome in 1966, Angell reflected on how “planned distractions” like cheerleading scoreboards and home run celebrations affected the experience of the game. “It will transform the sport into another mere entertainment,” he suggested, “and thus guarantee its swift descent to the status of a boring and stylized curiosity.” He saw it as an attempt to “build a following by the distraction and entire control of their audience’s attention” and branded it a “vulgar venture”; baseball, he argued, “has always had a capacity to create its own lifelong friends.”36 The scoreboard took the lead in reprogramming the stadium experience—and this even before video boards had reached a basic level of sophistication.

Kansas City’s Arrowhead Stadium—a football-specific stadium opened in 1972—pioneered the first legitimate instant replay scoreboard that could immediately show a previous play. The image was not particularly crisp—one reporter noted that when the board displayed the Chiefs’ mascot horse, Warpaint, “it reminded one of an old sepia western . . . and out of focus at that.”37 And yet the impact on fans and players was significant. Michael Oriard, a player for the Chiefs in the early 1970s, compared the experience of playing at old Municipal Stadium—a traditional, baseball-first park located in the midst of the city’s African American district—to that of the modern Arrowhead. The new stadium was more comfortable for both players and fans, he recalled, “but it also meant an altered relationship” between the two. “There were few distractions at the old ballpark to draw attention away from the contest on the field,” he observed. “I felt that we players were the focal point of all our fans’ attention. I sensed the fans’ presence, felt bound to them by a common passion.” At Arrowhead, this relationship between player and fan seemed to evaporate. Visitors to the new stadium “seemed less fans than spectators now, having paid ten dollars apiece to be entertained for three hours.” Their attention was divided: “The huge electronic scoreboard behind one end zone, with all its showy displays, competed with the players for the spectators’ attention.”38 This competition between players and scoreboard unraveled the connection between fan and game, converting visitors to passive spectators, no longer active participants in the contest and the moment.

FIGURE 72. Philadelphia Phil and Phillis (upper left and upper right, respectively) of the Veterans Stadium Homerun Spectacular. SPECIAL COLLECTIONS RESEARCH CENTER, TEMPLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES, PHILADELPHIA. ANTHONY BERNATO, PHILADELPHIA EVENING BULLETIN.

No modern stadium scoreboard possessed the capacity for drawing attention and clipping the cord between fan and player like that of the Louisiana Superdome. The stadium itself, opened in 1975, was remarkable for a number of reasons—among them its monumental size (spanning 680 feet and topping out at 273 feet), its extravagant cost ($163 million), and the well-publicized political intrigue and corruption accompanying its development.39 One of its most discussed characteristics was its space-age aesthetic: writers called it “a giant spaceship from a distant planetoid” and “Starship Superdome.” The “most futuristic feather of the whole mind-boggling building,” Jep Cadou of the Saturday Evening Post claimed, was its “giant-screen television.”40

The “television” was in fact six televisions, one for each side of the massive six-sided gondola hung from the roof. The apparatus weighed seventy-five tons and cost $1.3 million—a veritable bargain when compared to Philadelphia’s $3 million animatronic display. In addition to replays, the twenty-six-by-twenty-two-foot screens could also provide “isolated camera” and “slow-motion shots” that “television viewers have become used to.” The screens possessed, a stadium consultant noted, a color image “superior to a home television set.”41 Thus visitors to the Superdome, Cadou claimed, “will have the best of both worlds. They will have the excitement of being present ‘live’ and participating in all the action, without sacrificing the luxury of instant replays, isolation and slow-motion shots.”42

The Superdome was self-consciously modeled after the home. When still in its planning stages, a writer for Sports Illustrated reported that the stadium would have screens that “will show spectators instant replays and locker-room interviews just as if they were back in their living rooms.”43 Dave Dixon—a co-owner of the NFL’s Saints and key player in the building of the Superdome—imagined the space as a fusion of living room and stadium, claiming, “The viewer will have the best of both worlds: all the physical and emotional excitement of being there and the best seat in the house.”44 The creative use of cameras and replay in recent years had made watching games at home better than being in a stadium, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times noted. But the Superdome turned this on its head: “Watching football in here is just like being at home, only more so,” he wrote.45

Stadium managers planned to use the screens to simulcast the game on the field, for the benefit of those high in the stands and far from the field below. They also hoped to broadcast other games, attracting crowds to the Dome simply to watch huge televisions with others. They also sold advertising spots; ads for car dealers, banks, and resort communities were aired in between plays, prompting disgust from players and coaches.46 These commercials, many noted, were as invasive as advertisements on the television in one’s living room, and they were broadcast so loudly that those on the field were startled and distracted. A lineman for the Saints complained: “When we were calling plays or talking things over during time outs, it was pretty hard to hear.” Another player called the scoreboard “a damn nuisance.”47 And players weren’t the only ones criticizing the stadium invasion of the video screen. J. D. Reed of Sports Illustrated sarcastically suggested that the Superdome was a solution to the isolating capacity of television. “For years sociologists have been poor-mouthing television, noting that it separates people,” he wrote. “Americans don’t gather socially anymore because they are in apartments and in detached houses watching TV.” But in New Orleans, “now tens of thousands can gather in one room on a Sunday afternoon. To watch television.”48

Television bent the stadium and sport to its logic. Stadiums like the Astrodome and Superdome became living-room analogues—comfortable seats assembled around screens in air-conditioned rooms. Outdoor stadiums couldn’t model the living room so exactly, though they could mimic the logic of television’s incessant commercialized programming. But increasingly, the virtual identity of the stadium was surpassing its material significance. Lucrative television rights deals, particularly for professional football, redefined the economic significance of the stadium; the people physically present became relatively less important to those “attending” through televised broadcasts.

The debut of Monday Night Football on ABC in 1970 exemplified this shift. The program was under the steerage of Roone Arledge, who had honed his football production skills on college football broadcasts throughout the 1960s, developing a production style that, in his words, brought “the viewer to the game rather than the game to the viewer.”49 To do this, Arledge and ABC shot the game in innovative ways: from blimps, cranes, and helicopters, using handheld cameras to capture close-ups of cheerleaders and coaches; rifle microphones recorded the smashing of pads on the field and the buzz of the stands. His philosophy was to fill dead time, constantly engaging the television viewer with shots of the scene and commentary from broadcasters. Monday Night Football enhanced the televisual spectacle of ABC’s football production with nine different cameras, cutting-edge slow-motion technologies, and commentators who were stars in their own right—the opinionated Howard Cosell, the irreverent good-old-boy Don Meredith, and the winning Frank Gifford. Monday Night Football became the standard for televised professional football, and by the mid-1970s, NBC and CBS had embraced the Roone approach as well.50 Football was being produced less as sport than entertainment, celebrating the show around the game as much as the contest on the field.51

These new priorities fueled an increasing sense that the stadium itself hardly mattered except as a stage set for television drama. Some had anticipated, or at least speculated about, such a development since the late 1950s. An American League official had told sportswriter Roger Kahn in 1959 that baseball would survive competition from television by making ballparks “TV studios,” asking Kahn, “Do you know a better way to sell cigarettes and beer?” When a critic suggested that this plan seemed “unromantic,” the official responded, “It’s too late to worry about that now. The mistakes have been made. We went into the television business and now we have to make a living in the only way we can.”52 Frank Lane, an executive for the Baltimore Orioles baseball club, had told Newsweek in 1965, “Within ten years, the baseball parks of America will be mere studios for pay television.”53 Mark Harris—author of the acclaimed Bang the Drum Slowly, considered among the best sport-themed novels ever—argued this in a 1969 article in the New York Times Sunday Magazine. He claimed football stadiums were nothing more than a stage set for made-for-television drama, and the fans there were simply studio audiences designed “to give the illusion of a crowd enthralled, as canned laughter gives the illusion of humor.” The real interest of team owners were “the unseen millions in parlors, dens, family rooms and taverns, lulled by the illusion that they were spying upon an actual game, at no cost to themselves.”54 Most knowledgeable observers, like television critic Ron Powers, thought that stadiums had become “vast super-studios” by the 1970s, filled with fans who were no more than “paying extras”; by then, most club revenue came from television rights fees, not stadium gate receipts.55 With the construction of each new “cookie-cutter” stadium, there was a persistent and escalating sense that the average paying fan at the game was less important than the television consumer far from it.

If you can’t beat them, join them: architects and sports entertainers produced stadiums in the image of television and suburban comfort. Elaborate scoreboards and new video screens pumped advertising into the cracks of game play. Instant replays fixed people’s eyes upward. Visitors were told when to cheer and how to do it. Many of the stadiums’ residents—including sportswriters, fans, and players—outwardly objected to what they saw as a disruption to the game experience, sports’ subtle rhythms of play, and the relationship between players and their supporters. But team owners weren’t particularly concerned about the traditionalists; they had their eyes on the casual consumer who, in their eyes, might yawn during a game’s natural pauses. Clubs certainly enjoyed the additional revenue from video-board advertising—demonstrated by their eagerness to invest heavily in these expensive toys. Enough fans—a silent majority, it seemed—were willing to suffer through those ads in exchange for instant replay and other electronic amusements between plays.

Just as stadiums increasingly resembled one another materially, so too was the stadium experience routinized across the country. Scoreboard operators took their cues from other stadiums and spread this new logic of sports entertainment. Back in 1966, Houston’s Roy Hofheinz had boasted that thanks to all the stadium add-ons—the scoreboard, the clubs and restaurants, the padded seats, the air-conditioning, and the attractive usherettes—one didn’t have to “make a personal sacrifice to like baseball” in the Astrodome. In 1982, Dick Davis was hired to manage the Minneapolis Metrodome scoreboard, after spending the previous ten years operating the one at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium. Davis explained his scoreboard philosophy in terms that Hofheinz would have appreciated: “I want to use it as a reward for fans to be there in the first place.”56

If the exuberant scoreboard was a reward, it was a relatively democratic one, bestowed on all visitors (whether they wanted it or not). But modern stadiums like the Metrodome were also noteworthy for heaping particular “rewards” on thin slices of their most affluent patrons. Luxury stadium space—private suites, clubs, restaurants, and other forms of premium seating—achieved its greatest notoriety in Houston’s Astrodome, though it has existed in various forms throughout the history of stadium construction in the United States. Chicago’s Lakefront Park, built in 1878 and refurbished in 1883, boasted an early form of the luxury suite. The home of the National League’s White Stockings featured eighteen roofed boxes with armchairs and curtains, isolated from stadium riffraff atop the grandstand.57 Larry MacPhail’s exclusive Stadium Club at Yankee Stadium gained national attention in 1946. It was a “ritzy lounge beneath the stands where a select clientele of season boxholders can sup and sup in comfort far removed from the hoi polloi,” in the words of a Los Angeles Times columnist, who noted that this was an adaptation of private clubs at horse-racing grounds.58

Nearly all of the stadiums built in the 1960s had private clubs; Candlestick Park, District of Columbia Stadium, Dodger Stadium, Shea Stadium, Anaheim Stadium, and Busch Stadium each had spaces removed from the public and reserved for dues-paying members. Of course, Houston’s expansive outlay of fifty-three themed luxury suites, private clubs, and public restaurants inspired the envy of other cities’ civic leaders and sports businessmen beginning in the mid-1960s. By the 1970s, such envy was being materialized in stadium after stadium. When Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium opened in 1970, stadium promoters claimed its three-hundred-seat Allegheny Club and forty-two luxury boxes were “the epitome of spectator luxury.”59 Each eighteen-by-thirteen-foot box, accessible via elevator, accommodated nine visitors in its “completely private domain.”60 Philadelphia’s Veterans Stadium, opened in 1971, also housed a private stadium club for three hundred, as well as twenty-eight “Superboxes” on the press level.

But it was another Texas stadium that really doubled down on Houston’s model. Upon the opening of the Astrodome, Dallas Cowboys general manager Tex Schramm had told a Dallas reporter, “Everyone in sports is complaining that television is hurting their attendance . . . which it is, but that’s shutting the barn door after all the animals are out. Promoters have got to restyle their product to the times, and that means ultra-luxury stadiums, weather-conditioning, theater-style seats, private clubs, maybe even a night club atmosphere where people watch the game while waiters in tuxedos serve champagne and lobster. It’s not a civic responsibility for people to come out and watch us play. It’s our responsibility to get them out.”61 Texas Stadium, the Cowboys’ new home opened in 1971, materialized what for Schramm was the central lesson of the Astrodome—most provocatively in its soon-famous Circle Suites. Each of the 176 suites—“ranged on two levels . . . like the promenade decks of some gleaming ocean liner,” as described by a reporter—demanded a $50,000 bond, plus $1,680 for twelve season tickets and membership privileges in the Cowboy Club. What box holders got in return was “your own piece of real estate,” a sixteen-by-sixteen-foot empty concrete box to outfit as desired. Suite holders enjoyed easy and exclusive access to their boxes, with reserved parking places near elevators that escorted them up to soft-lit and carpeted corridors leading to their private rooms. Half of the purchasers were corporations, the other half individuals.62

FIGURE 73. Frederick Waggoner spent fifty-seven thousand dollars on his suite at Texas Stadium, which featured blue velvet chairs and drapes, commissioned art, and a crystal chandelier. AP PHOTO/FERD KAUFMAN.

A commentator anticipated that the opening of the stadium “should be something like opening night at the Met.” “The double row of millionaire suites should see a classic contest of one-upmanship as stoutly fought as any in the famed Diamond Horseshoe,” the writer continued, facetiously adding as an afterthought, “There will also be football.” Indeed, for many the football took a backseat to the Circle Suite luxury. The most “lavish” of the boxes was arguably that of Frederick Waggoner of Eldorado Oil & Gas. He spent fifty-seven thousand dollars on his suite, outfitting it with blue velvet drapes, empire-style chairs, wall-to-wall carpeting, velvet barstools, a glass-topped table with a massive gold vase of artificial roses, and commissioned wall paintings in oval gold frames. Combined, the decorations conspired to create an atmosphere “distinctly boudoir-like and 18th century [without] a hint of football in sight,” as a Los Angeles Times reporter described it. Neighboring boxes played on other themes, “from the antique to the modern, the businesslike to the sporting.” One holder outfitted his box like a Victorian saloon in old Ireland, with a solid brass bar rail, an old oak table carved with various names, a mirror advertising a whisky distillery, and a sign that warned, “Beware of pickpockets, drunks and loose women.” A financier outfitted his suite like a boardroom, with wood-paneled walls, regency-style leather chairs, and thick green carpet.63

For many, the Texas Stadium Circle Suites were conspicuous symbols of a distinctly Texan extravagance. Articles chronicled the design high jinks of wealthy Texans with much of the same fascination that accompanied the opening of the Astrodome six years before. “In true Texas style,” a writer for Travel magazine described the setting, “some of these suites, all with great views of the playing field, have elegant furnishings, original oil paintings, crystal chandeliers, walnut paneling and overstuffed chairs.”64 The home editor of the Dallas Morning News, after walking her readers through various Circle Suite design choices and details, concluded, “The glamour of the individual boxes carries on the tradition of the free-wheeling, Texas big rich!”65

For others, who noted the increasing frequency of the stadium luxury box across the national landscape, the “precious status symbol” of the Circle Suite spoke to a broader economic segregation within the modern stadium—and throughout American society more fully.66 Stadium operators hoped, one commentator explained, “to increase stadium revenue by soaking the rich for the satisfaction of sitting in opulence, separated from the commoners.”67 The proliferation of exclusive spaces within the stadium didn’t sit well with some. Charles Maher of the Los Angeles Times claimed, “The separation tends to dramatize class distinctions, and much more than the traditional separation between box seats and bleachers.” Unlike the simple spatial segregation of sports space, which had scaled seating by cost since the earliest days of grounds enclosure and admittance fees, “now the wealthy are separated by real walls, sitting in splendid isolation, presiding like princes at the joust.”68

Though the Circle Suites garnered much of the attention, becoming a symbol of socioeconomic stratification within the stadium, Texas Stadium was also notable for how it redefined access to the stadium more completely. The Cowboys’ previous home was the Cotton Bowl, in Dallas’s Fair Park, an area surrounded by neighborhoods that were almost entirely African American. Its crowds were eclectic and rough-and-tumble, shaped by the team’s blue-collar faithful. The new stadium was built in the white suburb of Irving, surrounded by parking lots and expressways. The Cowboys’ brash owner, Clint Murchison Jr., had hoped for a new stadium in downtown Dallas but had made enemies of the mayor and city council.69 Instead the Cowboys decamped for Irving, where an innovative financing scheme funded much of the new stadium. To buy season tickets, fans were first required to purchase stadium revenue bonds. The suites required the purchase of $50,000 bonds and brought in about one-quarter of the stadium’s total cost of $30 million.70 But much of the stadium was paid for through bonds attached to regular seating in the stadium bowl. Over three-quarters of the stadium’s 65,000 total seats required the additional purchase of low-yield bonds. To buy a ticket between the 30-yard lines ($63 dollars for the season), a Cowboys fan also had to buy a stadium bond worth $1,000.71 Seats outside the 30-yard lines required a $250 bond. Just 15,000 seats, located at the tops of the end-zone sections, were sold on a game-by-game basis; these required no bond but were quickly purchased at a cost of $7 per game. It was relatively easy for a working-class Cowboys fan to pick up a ticket for a game in the Cotton Bowl; it was quite difficult to attend a game at the new stadium, where access to tickets required season-long investment.

Texas Stadium epitomized the increasingly tightened access to NFL tickets across the league. Although professional football’s clubs continued to reap the rewards of escalating television contracts, the clubs also repeatedly raised ticket prices through the 1960s (and would continue to do so through the 1970s), claiming increased operational costs. League averages in 1970 were $6 per ticket, but most of these were scooped up by season-ticket holders—a system that priced out the young and working classes who couldn’t afford to buy an entire season’s worth of games.72 In Dallas, the average reserved season ticket had risen from about $4.60 per game in 1960, to $5.50 per game in 1965, to $7.00 per game in 1970.73 The additional burden of a ticket bond for the new stadium pushed this expense even higher. The Cotton Bowl’s masculine and often raucous crowd, shaped by its working-class fans, didn’t follow the Cowboys to the new stadium. Player Jethro Pugh remarked, “We gave up the shoeshine guy for the lawyer.”74

The pricing-out of many of the game’s hard-core fans was a troubling sign for many. “Watching the Cowboys play at home,” a columnist wrote, “has become the equivalent of joining a country club—and a darned expensive country club at that.” The title of an article in Esquire asked, “Wanta Buy Two Seats for the Dallas Cowboys? Struck Oil Lately?” Longtime Cowboys fans were priced out of seeing their beloved team—which many had followed through the club’s lesser years in the early 1960s at the old Cotton Bowl. Some took to calling the club’s new home “a rich man’s stadium” and “Millionaires’ Meadows.”75 A Cowboys supporter said of the stadium, “It kind of makes the whole thing a private club for the fortunate. You know the Cowboys have a lot of support among people who could never come up with $1,000, or even $250 for the privilege of buying season tickets. This is supposed to be a public stadium and yet its cost is well beyond most of the public’s reach.”76 Cowboys owner Clint Murchison admitted that because of the financing scheme the club “lost a whole group in the $12,000-to-$20,000-a-year salary range who could afford tickets at the Cotton Bowl but couldn’t afford to buy bonds.” However, he philosophized, “all America discriminates against people who don’t have enough money to buy everything they want.”77

Murchison’s justification certainly didn’t calm the angst of those either locked out of the stadium or put under a considerable financial squeeze to be there. The luxury suites were a conspicuous symbol of this new modern order. One Cowboys fan complained: “We keep hearing about those fabulous private boxes with the instant television replay systems. But how many people do you think have $100,000 to spend to get that kind of service?”78 The sense of a two-class stadium was only exacerbated when the City of Irving, located in a dry county, passed a special law that allowed liquor to be sold only in the Circle Suites and stadium club areas.79 A fan said, “They don’t serve alcohol to us poor slobs in the stands. Let’s face it, at Texas Stadium, I’m a second-class citizen.”80

When Miami Dolphins owner Joe Robbie began planning for a new 70,000-seat stadium north of the city in the late 1970s, he hoped to finance the project by selling $50,000 investment bonds to supporters—a plan devised from the financing of Texas Stadium earlier that decade. Broward County commissioner George Platt opposed such an approach, calling it “repugnant, because we wouldn’t want to build a facility for the needs of the wealthy.” Robbie defensively claimed that the bond approach didn’t cater to the rich; of his potential buyers, he said: “They’re not corporations or people who have inherited great wealth. They’re mostly upper-middle class people who are making $50,000 to $100,000 a year.”81 The Dolphins owner’s categorization of “upper-middle class” was predictably skewed; less than 4 percent of households made over $50,000 per year in 1979, when the national median income was $15,229.82

In spite of the complaints, team owners and architects increasingly committed stadium space to luxury suites and private clubs. The 83 suites in Kansas City’s Arrowhead Stadium, opened in 1972, rivaled those in Texas Stadium for opulence. Michael Oriard remembered, as a player at Arrowhead in the early 1970s, looking up to the suites from the field below and thinking that “behind the glass the social elite of Kansas City were sipping cocktails, nibbling on hors d’oeuvre, and following the game on closed-circuit television sets when it was not convenient to look down on the field—if they followed the play at all.”83 Thirty-three suites were installed at Rich Stadium in suburban Buffalo. New Orleans’s Superdome hosted 64 boxes—big party rooms for 30 people costing on average $25,000 per year.84 Ron Labinski, a stadium designer who would later found the influential architectural firm HOK Sport, noted in 1980 that nearly all stadiums built after 1967 had incorporated suites, “and in many of the older stadiums, we’re coming back and putting them in where we can.” San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium was adding 29 suites that year, and Anaheim Stadium was set for 112 as the stadium expanded to accommodate the relocating Rams of the NFL.85 Even Minneapolis’s Metrodome, endlessly celebrated by its promoters as a frugal antidote to some of its extravagant predecessors when it opened in 1982, housed 115 suites.86

In a decade of economic turmoil and stagnant working- and middle-class wages, the suite allowed the privileged a retreat from the stadium public into a private realm of food, drink, television sets, and personalized service. The inclusion of private luxury spaces in the stadium cultivated a new type of spectator: one who required certain standards of physical and social comfort to watch a game. These spaces also privileged a certain way of watching games: seated, dispassionately critical, expecting to be entertained by either the game on the field or the other entertainments at hand.87 These were spaces where, as a Los Angeles Times reporter said of Arrowhead Stadium’s suite holders, “If he or his friends don’t like the way a game is going they can always retire behind the glass-doored suite and shut out the world.”88 The slow and mundane, it seemed, was being programmed out of sport with the cultivation of a new kind of fan: a fickle consumer of highlights with no appetite for the subtle bridges between them.89

Plastic, loud, unrelenting, undemocratic, and standardized: these were qualities that disgusted traditionalists who valued sports as something more than a mere diversion. As old ballparks were torn down and new modern ones built to replace them in the name of progress, many thought the stadium had been corrupted, removed from its traditional status as an urban landmark, as an anchor of community identity, and as a site where great athletes did great things. To the purists, television seemed to be killing sport. Imagining a time when money and marketing seemed to take a backseat to the games, they called for a return to roots. Such complaints were at home among broader social critiques of capitalist waste, environmental degradation, and dehumanizing modernist belief systems reflected in everything from the war in Vietnam to urban planning and design.90

Baseball traditionalists, of course, saw plenty to dislike in the artificial turf, noisy scoreboards, and symmetrical outfields. In 1969, Mark Harris lamented how baseball’s “proprietors” had adopted the frenetic logic of television and the example of football. “Baseball is slow,” Harris reasoned. “It always was. It was slow in 1869.” He entreated baseball owners to look backward for inspiration, writing, “The man you need may be Henry David Thoreau, and what you need may be, not expansion but contraction, not speed but the nourishment of old roots, not closer fences or lowered scoreboards but a renewed connection between the game and its essential followers, not the eye of the camera but the vision of Time Past and Time to Come.”91

Emergent critiques of sport and the stadium weren’t limited to the boys of summer. Michael Oriard, just three years after concluding his playing career in the NFL, also lamented sport’s modern disconnection with the natural. In a 1976 essay, he argued that the ballpark and stadium were traditionally sources of psychic compensation for the loss of the frontier, antidotes to the worst effects of industrialization and urbanization. Sports like baseball and football were “symbolic reenactments of our struggle to survive in wild nature and vestigial clingings to our intimate relationship to pastoral nature.” This psychological need and relationship was undermined by the “artificiality of modern stadiums.” The standardization and denaturalization of stadiums degraded the quality of experience there, for both players and fans. As a player, Oriard recalled the “non-experience” of playing in artificial spaces like Busch Stadium, the partially roofed Texas Stadium, and, most of all, the enclosed Astrodome, which provoked a sense of “constriction” and “unreality.” In the monumental modern stadiums like Three Rivers Stadium and Riverfront Stadium, he felt alienated from the spectators. Conversely, “In the less pretentious stadiums,” he remembered, “we players seemed the focal point. . . . We were bound to our fans in a common undertaking. We were not merely ornaments or objects of the spectators’ amusement.” The stadium was losing its capacity to be “a source of psychic regeneration”; instead, it had become “a theater in which the spectator demands to be entertained by showmanship and victories, and where the player simply earns a salary.” Commercialized sport had maintained its “pastoral aspects” since the 1920s, but in recent years a new “dominance by technology signals a fundamental revision of American sport—a shift from mythic game to ostentatious spectacle.”92

When Roger Angell visited Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium in 1970, he found a building that was no longer a park but a machine—an anonymous non-place whose only distinguishing mark was an enormous stadium club hovering over the field, where the consumption of steak and cocktails rivaled the game. By the end of the decade, most major league cities had a new stadium like Pittsburgh’s—an engineered concrete cylinder filled with plastic seats, plastic grass, private clubs, luxury suites, noisy scoreboards, and sometimes a roof to block out the weather. Television, above all, ruled the games and the stadium experience, its logic of continual stimulation redefining in-stadium production. Many mourned the seeming loss of traditional sport, in which fans were engaged with the game, each other, and not much else—fans like those from Ebbets Field or Sportsman’s Park, where crowds were embodied participants in the game, talking to players on the field, jangling cowbells, and bellowing like farm animals.

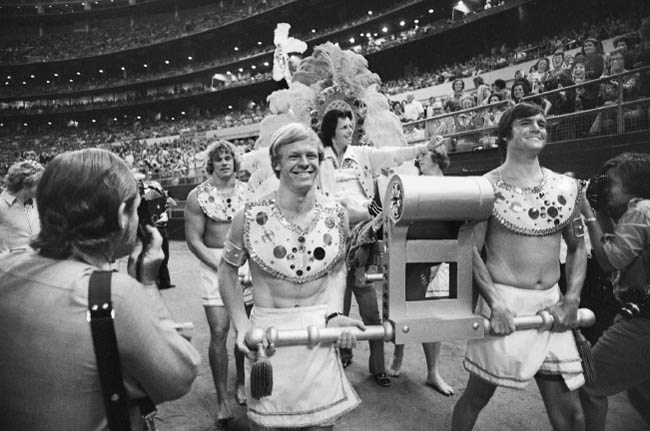

The famed “Battle of the Sexes”—Billie Jean King’s 1973 tennis triumph over Bobby Riggs in the Astrodome—perhaps expressed the state of sport, the stadium, and its culture at this time as well as any other event. Historian Bruce Schulman would later claim that the match “signaled the arrival of the women’s movement as a broad cultural force.”93 And yet it could as easily be seen as a farce. For any other match, King would walk out from the locker room to the court; on this day, she rode in on a gold divan borne by four bare-footed, bare-chested men. Her rival—the fifty-five-year-old former Wimbledon champion—arrived in a rickshaw pulled by five buxom women he called the “bosom buddies.” Divan and rickshaw ran an outrageous gauntlet of costumed characters from the nearby AstroWorld theme park; elegant women in evening dresses; men in the front-row seats wearing suits and holding signs with messages like “Whiskey, Women and Riggs” and “Who needs women?”; an eclectic mix of celebrities, including artist Salvador Dalí, singer Glenn Campbell, actress Janet Leigh, and football legend Jim Brown; and thirty thousand fans, many holding large banners that certainly distinguished the atmosphere of this match from most of the sport’s country-club affairs.94

The match was undoubtedly among the great spectacles of American sports history, a made-for-television event splattered across front pages of newspapers and magazine covers across the country. Roone Arledge, who had played such a pivotal role in making football a darling of television, paid over seven hundred thousand dollars for broadcast rights and raked in over one million in advertising for ABC. The heavily sponsored match was broadcast to a television audience of more than forty-eight million, in thirty-six foreign countries. Three hundred reporters covered the event.95

Those reporters drew many different conclusions from the match. Most focused on its theatricality—comparing it to Barnum’s circus.96 Many dismissed the event as mere show business.97 Gladys Heldman, the founder of the women’s professional tour, asked reporters before the match, “What do we get if Billie Jean wins, 30 Senators?”98 But others thought the match more significant. “Mrs. Billie Jean King struck a proud blow for herself and women around the world,” Neil Amdur wrote on the front page of the New York Times. “Most important, perhaps for women everywhere,” he claimed, “she convinced skeptics that a female athlete can survive pressure-filled situations and that men are as susceptible to nerves as women.”99 After the match, King described the win as a turning point in women’s sports and called it the apex of her career.100 Senator Hugh Scott, a Republican from Pennsylvania, said that King had “ratified the 26th Amendment” through her victory, ensuring passage of the proposed (and ultimately defeated) Equal Rights Amendment, which would ban discrimination based on sex.101

FIGURE 74. Billie Jean King emerges for the “Battle of the Sexes” atop a gold divan. RGD 0006-1973-0714, HOUSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY, HOUSTON METROPOLITAN RESEARCH CENTER.

The “Battle of the Sexes” would come to signify in shorthand a broader grassroots movement in women’s sport. King would be the face of that movement, which overlapped with a feminist agenda asserting women’s rights to control and enjoy their own bodies.102 But this event also suggested the state of big-time sports in the 1970s. Sports became out-and-out show business, both in the stadium and on television. The game itself was often secondary to the circumstances about it—shiny objects that competed with sports performances, crowding them out, so that spectator sport often seemed just sports-themed entertainment. For those who looked to sport for something more than mere entertainment, they found it had lost much of its transcendental capacities. Though today the Battle of the Sexes is remembered by many as an iconic social moment, an expression of the women’s movement and a repudiation of male chauvinism, its symbolic significance was muddled at the time by its carnivalesque production. It was an event both deeply meaningful and completely meaningless, a sporting event that, for many, had as much to do with sport as the kiss that King and Riggs shared—at the insistence of photographers—after the match.103

The Astrodome’s televised spectacle occurred at a time when the world was in the midst of profound economic, political, and cultural upheavals, changes that dramatically impacted urban life and the design of cities. The standardization of the stadium and its culture in the late 1960s and through the 1970s coexisted with increasingly prevalent critiques of the modern city and its design. Modernist architects and planners had wrought new downtowns of austere office towers, open plazas, and automobile throughways. Like the “machines for sport,” such spaces were criticized as placeless and anonymous, starkly functional and monumental, designed at a scale that dwarfed their users.104 As disgust with modernist planning and design gained steam, American cities—particularly in the industrial Rust Belt of the Northeast and Midwest—were also forced to grapple with a series of profound and escalating economic and social challenges. The loss of manufacturing jobs—to the Sun Belt, suburban areas, and increasingly abroad—wreaked havoc on urban economies and city residents. As demands for social services grew, tax revenues declined alongside federal support. Suburbanization continued apace, further concentrating poorer Americans in old urban neighborhoods that encircled central business districts rewritten by urban renewal and modernist planning. With the loss of manufacturing jobs, urban governments increasingly turned to culture as an engine of economic development. Public-private alliances developed new mixed-use entertainment districts featuring shopping malls, cocktail bars, themed restaurants, conference centers, gentrified housing, and sports stadiums. Some modernist stadiums served as anchors to such redevelopment projects—like Busch Stadium in the mid-1960s and the ostentatious Superdome in New Orleans a decade later. But as cities pivoted from making things to producing experiences, planners and architects turned to new forms of urban design.

Architecture made a “romantic turn,” rejecting the uniformity and cold rationalism of modernism. Unlike postwar modernists who scorned the styles of the past for a progressive and futuristic internationalism—a universal style that transcended all historical styles—postmodernists embraced local heritage and traditions. In a world that seemed ever more globally connected—marked by freer flows of people, goods, ideas, culture, and capital across regional and national boundaries—many Americans felt disconnected and looked to the past for stability and comfort. Designers tapped into these longings, insisting on the importance of place, as they attempted to materially construct a sense of community and security—while also distinguishing their cities from others in the competition for corporate investment. San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square, Boston’s Faneuil Hall, New York’s South Street Seaport, and San Antonio’s Riverwalk were all prominent examples of a new postmodern urbanism that celebrated place at a human scale; such developments often repackaged old and abandoned spaces of industry and commerce into outdoor pedestrian malls and entertainment zones. They directly challenged the tenets of modernism, deploying ornamentation, stylistic eclecticism, and historical reference in their new designs. The spaces could work as stage sets for visitors craving expressions of community and a sense of the past, of simpler times. It was a nostalgic architecture of not just function but fiction.105

Stadiums fit perfectly into this new brand of urban redevelopment. Sports teams are anchored geographically to specific cities and work as rallying points for broad and diverse communities of people. Thus they work particularly well at producing and amplifying a sense of place-based identity that can serve the growth strategies of politicians and business leaders.106 Just as cities compete for capital investment, their teams battle it out in city stadiums. City status is most easily marked in shorthand by the presence of “big-league” teams; this is as true today as it was in the 1950s when Milwaukee’s civic leadership lured the Boston Braves westward. The postmodern redesign of the stadium followed closely after the reinvention of American cities, and its symbolism overlapped seamlessly with the symbolic reconstitution of those cities. The new stadium—the postmodern stadium—could express a sense of history, tradition, and authenticity that seemed increasingly absent in a postindustrial age of political, social, and economic change.

When Baltimore unveiled plans for a new, downtown, baseball-specific stadium in 1989, New York Times architectural critic Paul Goldberger rejoiced, writing, “If it is half as good as the models and renderings suggest, it will represent a return to baseball as it should be; a game played on grass, not turf; under the sky, not a dome; in the middle of a city, not out on an interstate highway. This is a building capable of wiping out in a single gesture 50 years of wretched stadium design, and of restoring the joyous possibility that a ball park might actually enhance the experience of watching the game of baseball.”107 Goldberger’s reading of the planned ballpark perfectly channeled the intention of stadium designers: to build the antimodern, anti-artificial stadium; architects HOK Sport called it a “reaction to the cookie-cutter stadia of the 1960s and 1970s.”108 Plans called for a structure dominated by arched brick and steel trusses; the architects would avoid what a reporter called the “mausoleum effect of unrelieved concrete,” as expressed in the modern stadiums. Janet Marie Smith, Orioles vice president for planning and development, said that the designers wanted an intimate setting, with seats closer to the field than those at modern, multipurpose structures. “We studied the old ballparks to see what made them special,” Smith explained. They planned to blend the stadium into the cityscape rather than place it distinctly apart. The continual subtext, in describing the plans, was that the ballpark would not be another modern stadium but one that seemed to be from baseball’s past—the era of Ebbets Field, the Polo Grounds, and Sportsman’s Park. Orioles president Larry Lucchino emphasized this point, claiming, “We refer to it as ‘the ballpark,’ not a stadium. We try not to use the S-word.”109

FIGURE 75. The view from behind home plate at Camden Yards in 1992. The old B&O Warehouse, integrated into the ballpark, flanks the right-field wall. The urbanoid scene of Eutaw Street, inside the stadium gates, runs between field and warehouse. The corporate spectacle of downtown Baltimore is framed by the stands. AP PHOTO/TED MATHIAS.

Oriole Park at Camden Yards—a name that shoehorned two pastoral references and an industrial-era nod into five words—was the official title of the new stadium when it opened in 1992.110 Roundly celebrated, Camden Yards, as it was commonly known, was located in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, near the city’s Harborplace festival marketplace. Harborplace, designed by influential developer James Rouse, was one of the first historically themed, consumption-oriented, gentrified urban spaces when it opened in the early 1980s. Such developments were what Goldberger, writing seven years after his enthusiastic reception of the Camden Yards plans, would term “urbanoid environments”—carefully planned and sheltered places that seemingly bristled with urban energy and unpredictability.111 Pitched to middle-class, often suburban, consumers, these urbanoid spaces provided risk-averse, middle-class suburbanites with a sense of adventure.112 People gleaned textures of the authentic from gentrified urban spaces—festival marketplaces like Harbor-place among them. Visitors were afforded a simulated city experience in a built environment that signified authenticity and tradition through a historicist aesthetic.113

A new generation of stadium embraced an old urban idiom.114 Camden Yards featured heavy brick arches and revealed steel trusses. Its irregular dimensions fit into the existing streetscape. It integrated the adjacent railroad warehouse into the design, which seemed to stitch the park into the urban fabric. It employed a whole range of accents to signify pastness—ironwork details, retro-styled advertising, sand-blasted signage painted on brick, costumed service workers. Camden Yards expressed, in the words of cultural historian Daniel Rosensweig, “the fundamental and magical simplicity of an earlier era.”115

Camden Yards seemed to be everything the modern stadium wasn’t. It was a return to roots, recalling the early twentieth-century baseball parks that the modern stadiums had replaced. Comparisons to these old parks seemed endless. One commentator claimed, “Left field . . . is a homage to Yankee Stadium’s most memorable features. . . . Center field is an obvious nod to Wrigley. . . . Right field is pure Ebbets Field.”116 Another argued, “The asymmetrical playing field contains nooks and crannies in the outfield that will make playing defense there a thoughtful and artful vocation, in the mold of trying to learn all the angles at Boston’s Fenway Park.”117 A third wrote, “To most, the huge brick B&O Warehouse provided the park’s signature touch, looming large behind a sign-festooned right field fence reminiscent of Ebbets Field’s.”118 Though brand-new, the park seemed well-worn, well used, and thus more real and authentic. Baltimore Orioles general manager Roland Hemond admitted, “I feel like there’s already history here. It’s like we transported the tradition and didn’t lose it.”119 Baltimore star Cal Ripken said, “This may be the first game, but it feels like baseball has been played here before. It’s kind of strange. And really beautiful.”120

Many celebrated the connection of the park to the city around it. Physically and visually, Camden Yards seemed a sibling of the old traditional ballparks locked in their urban landscapes—parks like Ebbets Field and Fenway Park. Orioles owner Eli Jacobs claimed, “This is the city. The park is an integral part of the whole experience. It’s a natural part of the cityscape. It feels like it’s been here a long time.”121 Architects HOK Sport claimed that parks like Camden Yards “provide authenticity and symbolism, forging a bond between community and resident by illustrating a city’s best features.”122 Of the Baltimore park particularly, Tim Kurkjian of Sports Illustrated wrote, “It’s a real ballpark built into a real downtown of a real city.”123 Amid all this realness and authenticity, it was easy to forget that the stadium was brand-new.

The new park wasn’t celebrated as just a physical fit with the city but a spiritual and ideological one as well. Kurkjian argued, “It’s fitting that the new age of retropark is being celebrated already in Baltimore, a provincial, blue-collar, crab-cakes-and-beer town with thick roots and a thicker accent.” Orioles pitcher Mike Flanagan also linked the city’s blue-collar identity with a new stadium that seemed blue collar as well, claiming, “It’s a working-class park in a working-class town.”124 Washington Post writer Eve Zibert called it “the most embracing, class-leveling, elbow-rubbing baseball stadium of our dreams” and an expression of “democracy.”125

For all its seeming traditionalism and hardscrabble lineage, however, Camden Yards was luxurious—and in many ways quite modern—compared to its predecessor, Memorial Stadium. Though downtown, Camden Yards was adjacent to a freeway, convenient to suburban visitors; by the 1980s, Memorial Stadium was lodged into a majority-black residential neighborhood, notorious for its postgame traffic jams. The upper deck at Camden Yards was cantilevered; at Memorial Stadium, the second deck sat atop two-foot-wide support posts that obstructed plenty of sight lines. Camden Yards allowed its visitors more personal space; leg room for spectators in the new grounds varied between thirty-two and thirty-three inches, compared to the twenty-four to twenty-six inches at Memorial Stadium, and seats were nineteen to twenty-one inches wide, compared to sixteen to nineteen at the old place. Camden Yards featured sixty-one luxury suites, a private lounge, and a video screen. It was perhaps the best “stadium-as-studio” in the nation, boasting thirty-seven television camera locations staged throughout (compared to six at most parks), a television production studio, and an impressively framed view of downtown skyscrapers. Herb Belgrad, chairman of the Maryland Stadium Authority, asserted, “In the end we came up with state of art facilities and amenities as well as a traditional stadium”—though what made it “traditional” appeared to be as much about style as substance.126