4. ‘To attempt some new discoveries in that vast unknown tract’

Rediscovering the Forster collections from Cook's second Pacific voyage

ADRIENNE L KAEPPLER

This is an essay about discovery. Just as Cook made geographical discoveries during his three Pacific voyages, Joseph Banks, Daniel Solander, Johann Reinhold Forster and his son Georg, and others, made natural history discoveries. Cultural traditions and artefacts unknown in the West were discovered during the voyages and objects taken home to Europe to become part of private and museum collections. Some 200 years later, I set out on a journey to discover what had become of all the artefacts that had been collected during Cook's voyages. This detective work has engaged me on and off for some 30 years, and new discoveries continue to be made. This chapter focuses on the ethnographic collections made by Johann Reinhold Forster and Georg Forster and follows these collections to their present locations in the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and elsewhere.1

Cook, the Forsters and the Pacific Islanders: Differing visions of science, curiosity and art

In the London Gazetteer of 18 August 1768, Lieutenant James Cook noted that the aim of his first Pacific voyage was ‘to attempt some new discoveries in that vast unknown tract’. Five years later, in December 1773, during Cook's second voyage, Johann Reinhold Forster, speaking for himself and ultimately his son Georg, noted that his motivation for joining the voyage was the ‘thirst of knowledge [and] the desire of discovering new animals, & new plants’ for ‘the benefit which should accrue to science, and the additions to human knowledge in general’.2

Although both Cook and Forster were aiming for new discoveries, Cook's vision was originally focused on new geographic and astronomical knowledge, while Forster was searching for new biological and anthropological knowledge. Both Cook and the Forsters would succeed in making their new discoveries, although their successes owed as much to their luck in being the right people in the right place at the right time as to their visions and those of their patrons.

As far as Cook and the British Admiralty were concerned, the purpose of the first voyage was to observe scientifically the transit of the planet Venus from the vantage point of Tahiti, only recently discovered for the Western world by Captain Samuel Wallis. The purpose of the second voyage was to search for the Great South Land that geographers of the time believed to exist, and the purpose of the third voyage was to search for a northern passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Strictly speaking, all three voyages could be considered failures: the observations of Venus were disappointing, the Great South Land remained illusive, and a northern passage between the two oceans, if it existed, was blocked by thick sheets of ice.

The Forsters’ purpose on the second voyage was to contribute to the scientific knowledge of the world through collecting and publication. Strictly speaking, there were problems here also: many of the new plants and animals had been previously ‘discovered’ and collected by Banks and Solander during the first voyage. More significantly, the Forsters’ biological and anthropological specimens, although collected systematically, were subsequently scattered widely and there was no systematic publication of the botany, zoology, geology or anthropology by the Forsters or anyone else.3

The geographic information and mapping from these voyages, being of greatest relevance to the Admiralty, was the most systematically pursued and the results were quickly published. More than 200 years later, the description, analysis and publication of the scientific specimens and artefacts have still not been completed. Yet, as far as Pacific ethnography is concerned, the importance of these voyages has never been surpassed, either before Cook's time or since. While other European countries had preceded the British into the Pacific for more than two centuries, it was the advances in technology, navigation, medicine and scientific classification available in the latter half of the eighteenth century — as well as good luck — that were at least partly responsible for the success of Cook's voyages, even if some of the questions with which they set out remained unanswered.4

Cook's three Pacific voyages, and the voyages that came after him in the following century, may have opened to the Western world entirely new vistas of geographic and scientific knowledge, but these ‘discoveries’, so new to the Europeans, had been known to Pacific peoples for hundreds of years. Indeed, from the point of view of Pacific Islanders, the encounter has been more aptly described as ‘fatal impact’. Discovery and integration of knowledge operated in both directions. Cook and his companions had as much difficulty incorporating their new knowledge into eighteenth-century European views of the world as Pacific people had in fitting these strange white men and their curious ships into Indigenous Pacific world-views.

Europeans were astounded by the natural and artificial curiosities they encountered, appreciative of the arts, appalled by some of the customs and, in the following century, full of religious zeal to convert; while Pacific peoples quickly accommodated their world-views to incorporate these pale strangers and their jealous gods. Thus, in addition to the European visions of Cook and the Forsters toward science, curiosity and art, there is another equally important vision — that of the Indigenous peoples and their own views of science, curiosity and art — and a parallel line of enquiry, derived from oral tradition and memory, that should be incorporated into a broader view.

The ethnographic collections of Johann Reinhold and Georg Forster

As early as the sixteenth century, when Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch voyagers ventured into the great unknown, their compatriots (and men and women from other countries) were curious about the natural history and geography of exotic places, as well as the varieties of people found there and their works. Scientists especially were eager to learn about the varieties of environments, plants, animals and peoples — and most particularly the natural and artificial curiosities made by God and people. Books and visual images about these places were widely circulated, cabinets of curiosities proliferated and naturalists wanted first-hand accounts of these distant places as well as collections for study and classification.

Although considerable, the total collections of some 2000 pieces from Cook's three voyages,5 of which the second-voyage ethnographic collections of the Forsters form a major part, were not the largest ever made.6 The important point about the ethnographic collections from Cook's voyages is that they form the baseline collections for the Pacific Islands that were visited by Cook. They mark the end of strictly Indigenous fabrication and a point from which change can be postulated. Of Cook's three voyages, the collections made during the second voyage were the largest and the collections made by the Forsters on that voyage were the most systematic. Nevertheless, collections are by their very nature selective — dependent on the quality of contact as well as the length of time spent in an area — with the result that, of course, complete statements about the botany, zoology, or culture of any group visited during the voyages cannot be made.

Johann Reinhold and Georg Forster, along with their scientific assistant Anders Sparrman,7 acquired about 500 ethnographic artefacts during their visits to the Pacific Islands. They collected whatever they could, from whomever they could — acquiring a variety of artefact types and often collecting two or more of the same kind of artefact, just as they collected several natural history specimens of the same kind. As scientists, they travelled into the interior of the islands and interacted with people in their home villages, rather than just trading for what was brought to the ships for sale. However, except for the collection that went to the University of Oxford, which included a wide variety of artefact types, the objects were not distributed systematically. On the Forsters’ return to Europe, many of the artefacts were given away or sold to people and institutions that were, or could be, useful to the Forsters financially and/or for reasons of prestige or influence. Indeed, the Forsters probably collected duplicate objects specifically with the idea of selling them.8 Attempting to track down the entire collection made by the Forsters, therefore, is detective work, based on the documentation associated with the artefacts as well as in other institutions. Documents include original lists of the artefacts, letters and documents located in archives and libraries far from the artefacts, illustrations and auction catalogues. This essay presents a summary of what I have learned and located so far (see Tables 1–2 for details).

Of the 14 museums that hold collections made by the Forsters, the largest, widest ranging and most important collection is in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford University, England.9 This collection, for which there are some 200 catalogue entries,10 was given by the Forsters to the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University in February 1776, shortly after Johann Reinhold Forster received an honorary degree of doctor of civil laws in November 1775.11 As detailed in Tables 1–2, the Oxford collection includes examples of nearly every ethnographic object collected by the Forsters. Artefact types not included are few and, of these, representative examples from other island areas are usually found.12 Although there is no basket from New Zealand, there are nine baskets from Tahiti and Tonga and, while there is no Tahitian octopus lure, there is a Tongan octopus lure.

The next most important collection is in the Institute of Cultural and Social Anthropology, Georg-August University of Göttingen, which was purchased in 1799 for 80 thaler, after Johann Reinhold Forster's death. The Forster collection in Göttingen apparently encompasses what remained of his personal collection although, by 1799, it did not include many unique objects, having been diminished over the years by giving away and selling those pieces of most interest. One such sale, to Baron Heinrich von Offenberg from Mitau in 1779, comprised 41 pieces that Johann Reinhold Forster had initially retained for himself but was forced to sell to cover some of his debts.13 This group included a Tahitian breast gorget (taumi) that was described as ‘a collar braided out of cocoa fibres on small wooden sticks, beautified with bird feathers, fish teeth and mother of pearl, and trimmed with dog hair all around’.14 This may have been the best one he had left, as the taumi in Göttingen are not quite so ‘beautified’.

Also in the Göttingen collection are at least three pieces that entered the collection of the Academic Museum as a gift from one of the Forsters before 1782.15 According to G Wagenitz, these were Tahitian barkcloth, an octopus lure and a necklace from Tonga.16 Making a definitive list of the Forster collection in Göttingen has taken a great deal of work because it became intermixed with the larger Cook voyage collection that was assembled by George Humphrey in 1782. It is said that the Forster list includes ‘69 numbered entries with some 160 single objects’,17 but my count from the 1998 catalogue indicates a total of 93 single objects.18 The Göttingen collection contains two Maori baskets and it is a mystery why Forster kept these to the very end and gave none to Oxford.

A third important Forster collection is in Wörlitz in Germany. This collection of 32 pieces is housed in its own special building in the gardens of Wörlitz Castle, a large eighteenth-century, English-style, country house near Dessau. The objects were presented to Prince Leopold Friedrich Franz, a friend and patron of the Forsters,19 and derive from Tonga, Tahiti and New Zealand (the areas from which they had ‘duplicates’).

As mentioned above, a fourth collection of 41 pieces was once held in Mitau, Latvia. This collection has not been located and may have been destroyed during the Second World War. According to Otto Clemen, a letter from the Forsters mentions that Offenberg bought 41 objects from them in 1779, when they were in bad financial straits. Offenberg gave the collection to the Kurlandischen Gesellschaft fur Literatur und Kunst in Mitau in 1820. The objects were described as pieces of clothing and ornaments from ‘Tahiti’. In addition to the taumi mentioned above, they included barkcloth and a barkcloth beater.20

A fifth collection of 20 pieces from Tonga and the Society Islands has been identified in Berne, Switzerland. The collection descends from Wilhelmina Concordia Forster, Johann Reinhold Forster's daughter and sister to Georg. After five generations in the family, this collection is now owned by Hans-Joerg Rheinberger and is on loan to the Historical Museum in Berne. According to curator Thomas Psota, this collection consists of 12 pieces of barkcloth, four mats, a Tongan basket and flywhisk, an adze, and a fragment of a mask from a Tahitian mourner's costume.21

The Cook collection in the Museo di Storia Naturale in Florence houses another group of ethnographic objects that may derive from the Forsters. A 1778 letter in French from Georg Forster to Giovanni Fabbroni (now in the collection of the American Philosophical Society Library) accompanied a manuscript — also in French — entitled ‘Note on artefacts brought back from the Pacific Ocean’.22 This is a generalised description of the types of artefacts made by the peoples of the islands visited during the second voyage and appears to be a kind of ‘shopping list’ from which important patrons, such as the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Peter Leopold, could purchase artefacts for their cabinets of curiosity. But, if Duke Peter Leopold bought any, or what these items might have been, can only be inferred rather than documented, especially as the list could also describe the remnants of Johann Reinhold Forster's collection that went to Göttingen.

There are other small groups of objects that have associations with the Forsters, but lack documentation. In the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow, Scotland, there is a New Caledonian club which is probably the one depicted in the New Caledonia engraving published in the official account of the voyage. The Forsters corresponded with William Hunter, and other pieces in the Hunterian Museum may also have come from the Forsters. In the British Museum there is a unique carved wooden hand from Easter Island that was collected by the Forsters (and possibly other pieces).23

In the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology there is a shell trumpet from New Zealand that was given by the Forsters to Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant.24 The Cambridge collection contains 15 other objects, which might also have come from the Forsters, collected from islands visited during Cook's second voyage. Except for the shell trumpet, which is the only one the Forsters brought from New Zealand, the other pieces are relatively minor ‘duplicates’: barkcloth, clubs, fishhooks and tools.25 Two pieces in the Pennant collection, which do not seem to be ‘duplicates’, are a Tahitian noseflute and a bone chisel set in a wooden handle. These were probably originally obtained by Pennant from Banks, and both could be artefacts that are depicted in drawings from the first voyage.26

There are a variety of objects in German museums associated with the Forsters (usually Georg), but their provenance is far from clear. In Berlin, there once was a carved wooden bird from Easter Island (now missing) and two sets of Tongan panpipes, which were probably acquired during the second voyage by the Forsters. However, there are also objects from Hawai‘i that have been attributed to the Forsters. Hawai‘i was only visited on the third voyage and so these objects could not have been collected by them in the first instance.

In Leipzig there are several objects associated with Georg Forster, including a New Zealand comb said to have been given by Baron von Block, a Tahitian coconut cup from Conrady, a Tahitian fishhook from Professor Stuck of Jena, and perhaps others. In Dresden there are a few pieces given by Geheimrat Ludecus in 1885 that are said to be associated with Georg Forster, and possibly other objects. Who these collectors were, how they obtained objects from Forster, and whether Forster collected the objects himself in the Pacific islands are questions that have not yet been answered. Other museums in Germany, such as Bremen and Witzenhausen, as well as in Danzig, Poland, could also hold pieces collected by the Forsters. Again, most of these are relatively minor ‘duplicates’. In addition, a Tahition gorget, once in Göttingen, is now in the Neuchâtel Ethnographic Museum, through an exchange with Arthur Speyer.27

In 1777, in the Kunstkammer Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in Saint Petersburg, there were three pieces of barkcloth attributed to Johann Reinhold Forster, but the these pieces cannot be identified. It has been conjectured that objects from islands visited during Cook's second voyage were given to the theologian and historian, Cardinal Stefano Borgia, by Johann Reinhold Forster. At least part of Borgia's collection is now in the Pigorini Museum in Rome, but Ezio Bassani, in his study of this collection, has been unable to document that these objects were collected by the Forsters.28 It is possible that the 41 pieces of this collection could be part of the listing mentioned earlier, sent by Georg Forster to the Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Also yet to be located are the pieces of barkcloth attributed to Forster's collection in the 1787 sale catalogue of the library of Nicolao van Daalen and Christiano Plaat, and the items from the collection of Joshua Platt that were sold in a 1777 London auction, including objects from New Zealand, Tonga, New Caledonia and Tahiti. It is probable that these also derive from the Forsters, who had relatives in the female line named Plaat or Platt.29

Finally, Georg Forster gave Tahitian barkcloth to Caroline Michaelis, the daughter of a Göttingen professor. Caroline had the cloth made into a ball gown, which she described in January 1779 to her friend Julie von Studniz:

I received a large package of this cloth from him [Georg Forster] with a very nice note. To keep my promise, I had made a shepherdess outfit like one sees at the gala night, to wear to the ball. The material is white and the whole is decorated with blue ribbon, and is, in truth, very pretty. But you would have to see how much this dress, when I wore it for the first time, was touched and looked at, I can still say at present that it is unique and inimitable, until now at least, it will perhaps stay so, because I believe that Forster has no more of this material which is necessary for such a test.30

Classification

In the eighteenth century, anthropology was not considered a separate scientific subject. At that time, the study of human society and culture was largely an amalgam of observations made by navigators, missionaries and other travellers that had been processed by philosophers, historians and adventure writers, all of whom had distinct preconceptions about non-Western peoples that affected their selection and presentation of information about them. The study of language was viewed as a means of discovering relationships between peoples and was pursued and advanced by Johann Reinhold Forster during the second voyage. But Johann Reinhold Forster was steeped in eighteenth-century philosophy and the comparative tradition, while Georg Forster, who could classify by himself from the age of 11, was a man who noted what was presented to him.31 Johann Reinhold Forster, a natural historian, was trained in the new Linnean methods, while Georg Forster seems to have taken classification as a given and to have gone on from there. Although they studied natural history together, the father did it consciously toward an end, primarily as classification and within the comparative tradition as well as for his own advancement, while the son just learned it as part of his upbringing. Thus, as he was more of an empiricist, the materials presented by Georg Forster are more useful to ethnography today and especially to Pacific Islanders — for whom Johann Reinhold Forster's opinions of how they relate to the Ancient Greeks and other classical or Western cultures are largely irrelevant. In Georg Forster's list and description of artefacts that were sent to Oxford, the materials are classified by area, as is the listing sent to Fabbroni. On the other hand, the list prepared from the Göttingen collection was arranged by artefact type, as is the listing in Wörlitz. The Sparrman collection in Stockholm is also listed by artefact type. The artefact type lists were similar to the systematic organisations of plants and animals and could be prepared by a knowledgeable taxonomist, while the area listings required ethnographic knowledge and could only be accomplished by someone like Georg Forster who had collected or studied the objects.

The Oxford collection, because it was accompanied by a detailed listing of the artefacts by area, is the key for understanding all second-voyage collections — and, indeed, the material culture of the islands visited during this voyage. In addition, the illustrations by the official artist on Cook's second voyage, William Hodges, and by Georg Forster provide important additional information for identification, use and significance. When used together, the Forsters’ artefact collections, their writings about them, and the illustrations form a treasure of ethnohistorical research for the islands that were visited on their voyage.

The engravings in the official account of the second voyage

Finally, further information about the objects collected by the Forsters can be found in the five plates of artefacts that were published in the official account of Cook's second voyage.32 These engravings depict artefacts that were collected by the Forsters from New Zealand, Tonga, Marquesas, New Hebrides and New Caledonia, most of which are (or were) in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford.

The New Zealand engraving includes the hafted adze (toki pou tangata) and the scarifier that are now in Oxford, as well as the shell trumpet which is now in Cambridge, all of which belonged to the Forsters. The Tongan engraving depicts several objects that are now in Oxford: the basketry-covered wooden bucket, the spear, the panpipe and probably the bow. The flat basket was at one time in Danzig (and attributed to Johann Reinhold Forster).33 The comb, club and feather frontlet have not yet been identified. The Marquesas engraving depicts four pieces that are now in Oxford: the seed gorget, the rope gorget, the shell and feather headdress, and the fan. The club in the engraving is unaccounted for, although it may be in the British Museum. The Forsters gave the British Museum the unique Rapa Nui wooden hand, and it is conceivable that they also gave this unique (from the second voyage) club as well.

The Vanuatu (New Hebrides) engraving depicts a panpipe that is now in Oxford. Other pieces that were probably once in the Pitt Rivers Museum but have not yet been found include the bow, the spear and the nose stone. The club is unaccounted for, unless the engraving is a very bad depiction of the club that is now in Oxford. The New Caledonian engraving probably depicts the hat that was at one time in Oxford (this was the only one collected during the voyage). The spear thrower, the spear, the two clubs in the centre, and the comb are in Oxford. The long-bladed club is now in Glasgow. The extraordinary adze, however, has yet to be identified.

The Forsters returned from the Pacific on 30 July 1775 and by January 1776 the artefacts had been sent to Oxford,34 which means that the drawings of the objects were made between August and December 1775. Although the New Zealand engraving gives no artist's name for the drawing on which it is based, Peter Gathercole conjectures that it was done by Georg Forster.35 In the other four engravings, the drawings are attributed to [Charles] Chapman. Later in 1776, Georg Forster stated in his account that ‘plates, engraved at the expence of the Board of Admiralty, are the joint property of captain Cook and my father’,36 even though, by this time, Johann Reinhold Forster was no longer permitted to contribute his writings to the official account. Thus, it makes perfect sense that while Johann Reinhold Forster believed he was going to have significant input into the official account he would use the artefacts he and Georg Forster had collected to illustrate it. In spite of Johann Reinhold Forster having no part in the text of the official account, the artefacts collected by him and his son have made a significant contribution to the visual history of the second voyage. Fortunately, many of the depicted artefacts have been located. For those that have not, the illustrations provide a guide of what to look for.

Tonga

The collection from Tonga could be described as a jewel among the treasure collected by the Forsters on the second voyage. Tahiti and New Zealand were visited during the first voyage and baseline collections were gathered and written about by Cook and Banks and illustrated by Sydney Parkinson and others. The second-voyage collections from the Marquesas, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Vanuatu (New Hebrides) and New Caledonia are also extremely important, but contact was brief and the collections small. From Tonga, however, the collections are large and varied, and contact was extensive.

In 1778 Johann Reinhold Forster noted that Tongan ‘utensils, manufactures, agriculture and music bespeak their inventive genius and elegant taste.’37 His admiration is manifested in the Forsters’ Tongan collection, which includes many objects that are no longer made but are seen today by Tongans as unique exemplars of their history.38 The Forsters were scientists but, to Tongans today, these objects have their importance as treasures of their cultural heritage. Because ethnographers are responsible both to science and to the people they study, my research uses the Forsters’ science in the service of ethnography and Polynesian cultural identity.

Ethnologists today combine traditional anthropological concerns with post-structuralist concepts of identity and the social and cultural construction of the self. The cultural politics that derived from colonisation and decolonisation are becoming ever more potent in a world concerned with national identity and the construction of contemporary traditions from traditional systems of knowledge. Many aspects of custom and identity are based on objects, manuscripts and illustrations that are now in museums. These items, and their curators, are continually consulted by a wide range of people — from the descendants of their makers to interested laypersons. Understanding the politics of culture and identity, how modern traditions are constructed through social and political changes, and why it is imperative that such concepts be understood in our explosive world are an ethnologist's concerns and are met through research, publication, exhibits and websites, as well as by assisting Indigenous individuals and groups to carry out their own researches on these subjects, especially where traditional cultural forms and systems of knowledge are becoming endangered.

The modern Pacific Islander sits in the midst of many worlds. Many of their rituals and presentations still exist as part of the modern world and traditional artefacts can be used to understand life in its present form. Although objects can no longer be exchanged for a person and women who use tabu artefacts are not subject to sanction, many are still used in traditional ways: during funerals, investiture of titles, dance and marriage, as well as for the advancement of tourism. Locating, documenting and interpreting significant artefacts are important steps in the study of Pacific ethnohistory. The collections and the works of the Forsters are important elements for cooperative work between ethnographers and Indigenous Pacific peoples, who are now part of an international world but who value their modern lifestyle that comprises Indigenous traditions, Christianity and modernity.

Just as Europeans are interested in admiring the churches and clothing of eighteenth-century England and Germany and have no problems with riding in cars and aeroplanes rather than horse-drawn carriages, so Pacific Islanders no longer live in the eighteenth century but yet remain interested in the temples, tools and clothing of their past. Indeed, for many Pacific Islanders, their eighteenth-century material culture is still important and used during life crises and important events.

Having predicted the ruin of Indigenous cultures, Georg Forster would undoubtedly be happy to know that, in this case, he was wrong.

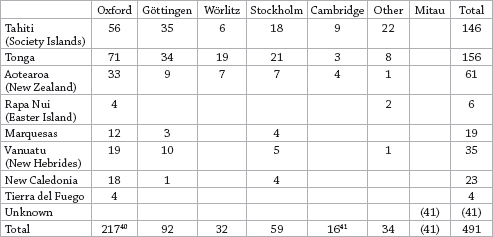

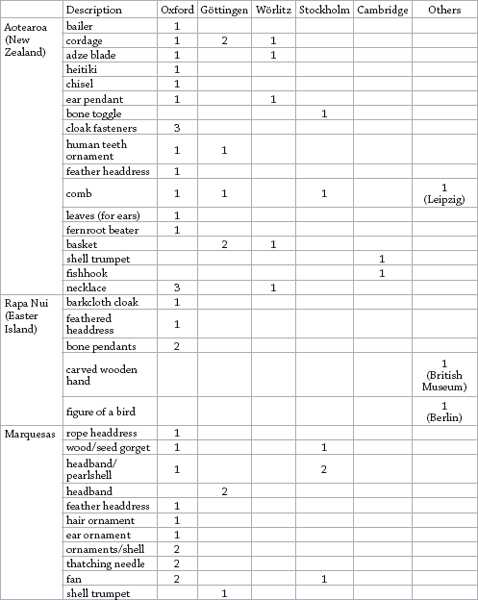

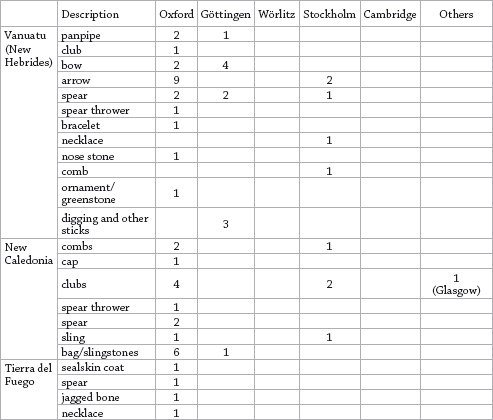

Table 1

Totals of objects in the Forster collections from the second Cook voyage:39

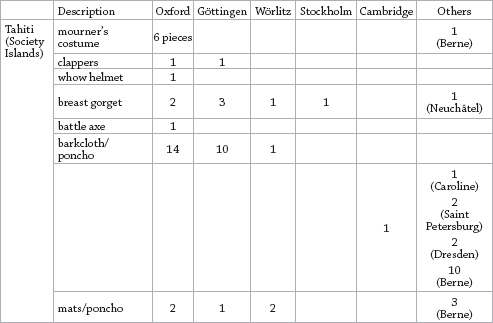

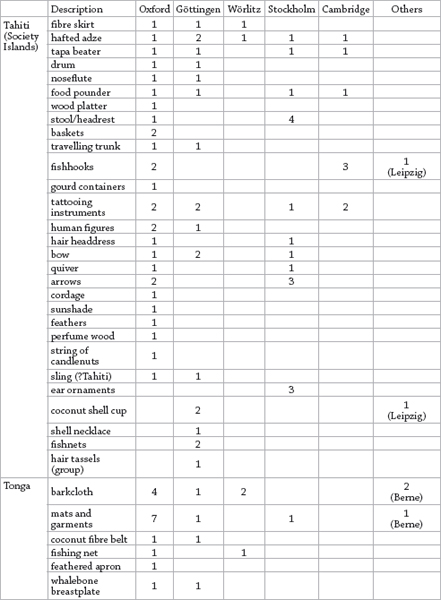

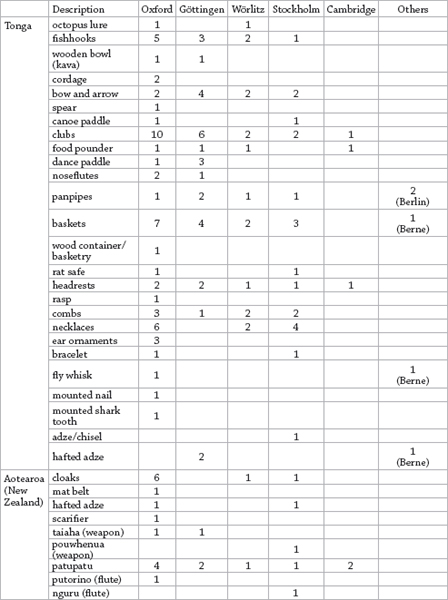

Table 2

Objects in Forster collections by area and artefact type:

Notes

1 An earlier version of this paper was published in German: A Kaeppler, ‘Die ethnographischen Sammlungen der Forsters aus dem Südpazifik: Klassische Empirie im Dienste der modernen Ethnologie’ (‘The Forster ethnographic collections from the South Pacific: Science in the service of ethnography’), Georg Forster in Interdisziplinarer Perspektive, Akademie Verlag, Berlin, 1994, pp. 59–75, and some of the information was included in Kaeppler, ‘The Göttingen collection in an international context’, in Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin and Gundolf Krüger (eds), James Cook: Gifts and Treasures from the South Seas, Prestel, Munich, New York, 1998, pp. 86–93. The data in the tables has been re-analysed and updated.

2 Michael E Hoare (ed.), The Resolution Journal of Johann Reinhold Forster 1772–1775, 4 vols, The Hakluyt Society, London, 1982, vol. 1, pp. 69,72.

3 No official scientists were taken on the third voyage, but many biological and cultural objects were collected. A significant part of these went into the private museum of Sir Ashton Lever, ‘The Holophusicon’. This museum was transferred by lottery and eventually sold at auction in 1806 in more than 7000 lots, which are now located in many parts of the world.

4 Indeed, some 70 years later, when the American Charles Wilkes set sail into the Pacific on the United States Exploring Expedition, he too was looking for new discoveries and had much the same purpose as Cook's second voyage — that is, to explore the South Polar Sea to find out if land or a continent existed there, to provide charts for safer navigation, to extend the boundaries of science and to promote trade.

5 Kaeppler, ‘Artificial Curiosities’: Being an Exposition of Native Manufactures Collected on the Three Pacific Voyages of Captain James Cook, R.N., at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, January 18, 1978–August 31, 1978: On the Occasion of the Bicentennial of the European Discovery of the Hawaiian Islands by Captain Cook, January 18, 1778, Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu, 1978.

6 The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–42 collected at least 4000 ethnographic objects, nearly double the total ethnographic collections made during the three Pacific voyages of Captain Cook. In addition, the United States Exploring Expedition collected 2000 birds, 150 mammals, 1000 corals, crustaceans and molluscs, numerous fish, and 50,000 plants (see Herman Viola and Carolyn Margolis (eds), Magnificent Voyagers, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC, 1985). Like Cook's first two voyages, Wilkes was accompanied by scientists who collected, classified, and published, as well as artists who depicted places and events.

7 Jan Soderstrom, A. Sparrman's Ethnographical Collection from James Cook's 2nd Expedition (1772–1775), Ethnographical Museum of Sweden, Stockholm, 1939.

8 Several years earlier, when Johann Reinhold and Georg Forster first arrived in London, they ‘supported themselves by selling Tartarian coins, fossils, idols, manuscripts, and other artefacts brought from their Russian expedition’ and now they had even more exotic objects (Hoare, The Resolution Journal, p. 21).

9 See Peter Gathercole, From the Islands of the South Seas 1773–4: An Exhibition of a Collection Made on Capn. Cook's Second Voyage … by JR Forster, Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, [1970]; Jeremy Coote, The Forster Collection: Pitt Rivers Museum, Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, http://projects.prm.ox.ac.uk/forster/home.html, accessed 5 March 2007.

10 Counting individual pieces, such as arrows, the number is closer to 220.

11 Hoare, The Resolution Journal; Jeremy Coote, Peter Gathercole & Nicolette Meister (with contributions by Tim Rogers & Frieda Midgley), ‘“Curiosities sent to Oxford”: The original documentation of the Forster Collection at the Pitt Rivers Museum’, Journal of the History of Collections, vol. 7, no. 2, 2000, 177–92.

12 The fishing net in Oxford is said to be Tongan, while two very similar nets in Göttingen are said to be Tahitian.

13 See Otto Clemen, ‘Briefe von Reinhold und Georg Forster in Mitau’, Dr A Petermanns Mitteilungen aus Justus Perthes’ geographischer Anstalt, Justus Perthes, Gotha, 1917, p. lxiii.

14 Clemen, ‘Briefe’, trans. Donald Hirsch.

15 Established in 1773 at the Georg-August University as a research and teaching institution, the Academic Museum housed anatomical, geological, historical, natural and cultural collections. Johann Friedrich Blumenbach had succeeded in acquiring a few Pacific artefacts from Joseph Banks in 1771 and Georg Forster in 1781.

16 Wagenitz found these entries in the old register (personal communication).

17 Manfred Urban, ‘The acquisition history of the Göttingen Collection’, in Hauser-Schäublin & Krüger, James Cook, p. 71.

18 Hauser-Schäublin & Krüger, James Cook.

19 Ernst Germer, ‘Zu Georg Forsters Polynesien-Sammlung von Wörlitz’, Georg Forster: Naturforscher, Weltreisender, Humanist und Revolutionar, Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten, Wörlitz, 1975, pp. 187–99.

20 Clemen, ‘Briefe’, p. 20.

21 Thomas Psota, ‘Von dem Gesellschafts-und den Freundschaftinseln: Gegenstände der Forster-Sammlung in Bern’, in Horst Dippel and Helmet Scheuer (eds), Georg-Forster-Studien V, Kassel University Press, Kassel, 2002, pp. 267–82; Ruth Dawson, ‘Collecting with Cook: The Forsters and their artifact sales’, Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 13, 1979, 5–16.

22 This manuscript is now in the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington: see Kaeppler, Cook Voyage Artefacts in Leningrad, Berne, and Florence Museums, Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu, 1978, pp. 71–4.

23 Kaeppler, ‘Tracing the history of Cook voyage artefacts in the Museum of Mankind’, The British Museum Yearbook, 3, British Museum, London, 1979, pp. 167–97.

24 Gathercole, ‘A Maori shell trumpet at Cambridge’, in G de G Sieveking, IH Longworth, and KE Wilson (eds), Problems in Economic and Social Archaeology, Duckworth, London, 1976, pp. 187–99.

25 The Cambridge collection also includes three pieces from Tierra del Fuego (also from Pennant). These would have been originally obtained from Banks, as they are depicted in drawings from the first voyage.

26 The Tahitian barkcloth beater in the Pennant/Cambridge collection might also be from Banks. There are further objects that probably belonged to Pennant, possibly sourced from Forster, depicted in three drawings that were pasted in Pennant's copy of Cook's voyages that is now in the Dixson Library (see Kaeppler, ‘Artificial Curiosities’, p. 148 [fig. 264], p. 156 [fig. 286], p. 240 [fig. 519]).

27 Roland Kaehr, pers. comm.

28 Ezio Bassani, Cook, Polinesia a Napoli nel Settecento, Calderini, Bologna, 1982, p. 22.

29 M Hoare, pers. comm.

30 Erich Schmidt (ed.), Caroline: Briefe aus der Frühromantik, nach Georg Waitz vermehrt hrsg. V Erich Schmidt, 2 vols, Insel-Verlag, Leipzig, 1913, vol. 1, pp. 9–10.

31 Hoare, The Resolution Journal, pp. 12, 17.

32 James Cook, A Voyage towards the South Pole and round the World, Performed in His Majesty's Ships, the Resolution and Adventure, in the Years 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775, 2 vols, W Strahan and T Cadell, London, 1777.

33 Johann Reinhold Forster and his family lived near Danzig and Georg Forster was born there.

34 Coote, Gathercole and Meister, ‘“Curiosities sent to Oxford”’.

35 Gathercole, ‘A Maori shell trumpet at Cambridge’, p. 199, note 11.

36 Quoted in Gathercole, ‘A Maori shell trumpet at Cambridge’, p. 199, note 10.

37 Johann Reinhold Forster, Observations Made during a Voyage round the World, London, 1778, p. 235.

38 These objects are a unique and important source of information about Tonga in the eighteenth century. In my article, ‘Eighteenth century Tonga: New interpretations of Tongan society and material culture at the time of Captain Cook’ (Man, vol. 6, no. 2, 1971, 204–20), I have written about eighteenth-century Tonga, based on the Forster collection in Oxford, and summarise the importance of the objects for understanding social structure and other cultural traditions.

39 This is based on the original lists. Some of the objects are now ‘missing’.

40 For a full list of the Oxford collection with more information see Coote, Gathercole and Meister, ‘“Curiosities sent to Oxford”’.

41 This is a ‘best guess’ compilation. Some of these objects from the Pennant collection in Cambridge may have come from Banks but, because we know the shell trumpet came from Forster and because of the ‘duplicate’ character of the others as items, these 16 pieces are likely to be from Forster. See also Julia Tanner, From Pacific Shores: Eighteenth-Century Ethnographic Collections at Cambridge, University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge, 1999.