Whatever their obvious differences, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726, 1735), two of the most well-known texts of the early eighteenth century, share a deep and abiding engagement with utopian possibility.1 In their own ways, both narratives valorize retreat from worldly vice and the resumption of simpler, ostensibly more virtuous ways of living. Although Crusoe and Gulliver run afoul of domestic quiescence, spurred by restlessness and curiosity, they stumble upon unknown lands that shield them from the excesses of the city and the depravities of the court. In Houyhnhnmland, Gulliver proclaims, “No Man could more verify the Truth of these two Maxims, That, Nature is very easily satisfied; and, That, Necessity is the Mother of Invention” (Swift, Prose Works 11:276). He sounds a lot like Crusoe, as well as Crusoe’s real-life model, Alexander Selkirk, and even the Siberian exile. After his banishment by the Houyhnhnms, Gulliver seeks a desert island of his own, concluding that the fate of a castaway would occasion “greater Happiness” than that of a “first Minister in the politest Court of Europe”—echoing Crusoe yet again (11:283). Granted, the assertion is blunted in both novels: in Defoe, Crusoe resumes his rambling; in Swift, Gulliver can only incompletely transform himself. Still, Raphael Hythlodaeus, in his refusal to advise kings, might have commiserated, identifying with their failed idealism.

For some time, critics have regarded Swift as the eighteenth century’s principal—though also most skeptical—heir to the utopian tradition. Swift went straight to the source, borrowing from and responding to Thomas More himself, specifically his conceit of the jaded but clearly fictitious traveler returning from wonderful new lands. Claude Rawson argues that “More’s Utopians [are] in some ways ancestors of the Houyhnhnms” (Gentle Reader 19).2 More, of course, makes an appearance in part 3 as the only Englishman and, indeed, the only modern singled out among the great men of the past whom Gulliver conjures to the present. Some commentators have gone back further to find precedents for Swift’s utopianism in authors such as Virgil (Landa; Doody, “Insects, Vermin, and Horses”) and Horace (W. Anderson) and in historical figures such as Lycurgus of Sparta (Halewood, “Plutarch in Houyhnhnmland” and “Gulliver’s Travels, I, vi”; Higgins, “Swift and Sparta”) and Cato the Younger (Kelsall; Aravamudan, Tropicopolitans 135–45). There is perhaps a more immediate predecessor to Gulliver’s Travels in Anne Marie Louise d’Orléans’s L’Isle imaginaire (1658), or The Isle of Dogs, where greyhounds rule over lions, monkeys, foxes, and other animals.

Gulliver wants to stay with the Houyhnhnms, and only secondarily to live in seclusion, but both wishes are frustrated by Swift’s sense of the limitations of human nature and the universality of it across geographic distance. Gulliver’s partial reform, in part 4, entails social debilitation, whereas Crusoe’s transformation enables the endless journeys of The Farther Adventures (1719), betokening a mostly untroubled adventurism. Again and again, Gulliver returns home, and actually he encounters home, allegorically, almost everywhere he goes. In this sense, Swift’s fabulous terrains recall another body of literature: Menippean satires, such as Joseph Hall’s Mundus Alter et Idem (1605), and secret histories, such as Delarivier Manley’s New Atlantis (1709) and Eliza Haywood’s Memoirs of a Certain Island Adjacent to the Kingdom of Utopia (1725). These narratives imagine what Robert Appelbaum calls “anti-geography,” depicting foreign space through sociopolitical allusions and using distant lands only to reflect familiar problems in funhouse shapes and sizes (“Anti-geography”). Samuel Brunt employed a similar technique in his Voyage to Cacklogallinia (1727), which replaces Swift’s horses with giant chickens that mingle French and English shortcomings. Satire and utopia are complementary, perhaps inseparable, insofar as utopia, too, exposes the insufficiencies of reality, while satire often betrays belief that wrongs can be righted.3 In Gulliver’s Travels, however, satire might seem to crowd out hope, Ernst Bloch’s sine qua non of the utopian impulse. Thus Gulliver’s globe collapses inward, reminding him at every turn of human—and specifically European—failings and the difficulty, if not impossibility, of outstripping them. One thinks of the truly global reach of Samuel Johnson’s “Vanity of Human Wishes” (1749), in particular the poem’s famous first lines:

Let observation with extensive view,

Survey mankind, from China to Peru;

Remark each anxious toil, each eager strife,

And watch the busy scenes of crouded life;

Then say how hope and fear, desire and hate,

O’erspread with snares the clouded maze of fate.

(6:91–92)

A feeling of claustrophobia sets in, and Gulliver retreats: to Redriff, to Nottinghamshire, to his horse stable, and to the recesses of his supposedly addled brain, the location of misanthropia. Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen’s Simplicius Simplicissimus (1668), Johnson’s Rasselas (1759), and Voltaire’s Candide (1759) give us variations on this theme, disenchanting their eponymous heroes and retiring them in small sanctuaries that rebuke the grandiosity of youthful expectations. In a letter to Alexander Pope, Swift affirmed, “I have got Materials Towards a Treatis proving the falsity of that Definition animal rationale; and to show it should be only rationis capax. Upon this great foundation of Misanthropy (though not in Timon’s manner) the whole building of my Travells is erected” (Correspondence 3:103). There is, nonetheless, something of the Athenian hermit in Gulliver, who ends up preferring horses to his own family.

In this chapter, I show how Swift posits and satirizes—but also resituates—utopia. In “Of Solitude,” the first chapter of Crusoe’s Serious Reflections (1720), Defoe makes utopia a state of mind available anywhere, even in London. Swift undertakes a similar transformation when he has Gulliver replicate Houyhnhnmland through memory and fancy, enacting its ideals in the seclusion of his rural home and stable and forming oblique and unequal relationships with both humans and horses. In each new land, the horizon of possibility seems at first to expand before shrinking back as the allegory comes into focus and we begin to make sense of the surroundings. Finally, though, once he returns home, Gulliver recovers remnants of these utopias in his tightly circumscribed refuge. Hope might be attenuated, stripped down to almost nothing, but what remains is surplus desire, along with a willingness to carry that desire to some sort of fruition. It has been argued that Swift insisted on the unassimilable spaces that geographers denied (Neill 83–119) and that Gulliver returns home commensurably fragmented, riven by a redirection of imperial power back on the would-be colonizer (Hawes, British Eighteenth Century 139–68). What I emphasize here is an offsetting universalism and the way it ultimately compacts a sense of self. Over and over, Swift dismantles geographic enclaves, revealing their permeability by the constants of human nature and thereby demonstrating the inability of geography alone to insulate radically different realities. By the end of the novel, the imaginary Houyhnhnmland becomes part of Gulliver, an ideal buried in the mind that makes contact with the world in acts of love toward horses and hostility toward humans. His inner utopia is a stubborn belief disbelieved by everyone else, an alienated idealism predicated on its own intransigence. I would not quite restore a happy ending to Swift’s pessimistic novel, easily the bleakest work I focus on here. Rather, I want to show how the dimensions of happiness are drawn in further still, how the changing scope of utopia contracts from the scale of continents and islands and their large-scale societies to the space of a besieged individual and, very tentatively, a select few others. It is not a total loss, but what is recuperated is now shrunk to nearly Lilliputian dimensions.

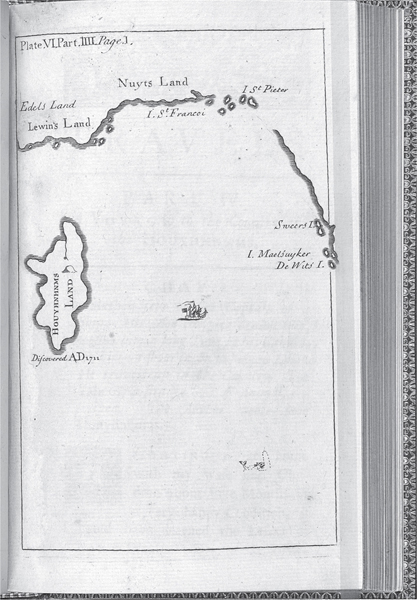

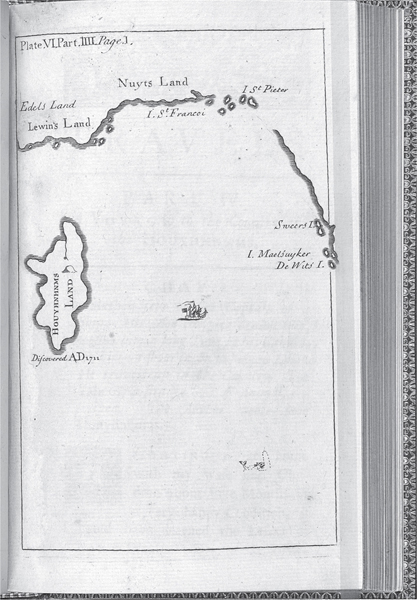

For a moment, and perhaps only a moment, Swift would have us believe his far-fetched lands are out there, that utopias lie waiting for discovery. Gulliver ventriloquizes the “plain style” of actual travelers and the jargon of sailors and natural philosophers (Sherbo; P. Adams 142–45; Passman; F. Smith; Hawes, “Cousins Sympson and Simson”). Repeatedly, he protests—too much—that his information is factual, and his editor affirms, “There is an Air of Truth apparent through the whole; and indeed the Author was so distinguished for his Veracity, that it became a Sort of Proverb among his Neighbours at Redriff, when any one affirmed a Thing, to say, it was as true as if Mr. Gulliver had spoke it” (11:9). It is one of many jokes, but Swift takes pains to push his settings beyond the limits of existing knowledge of the world, exploiting gaps and uncertainties in contemporaneous cartography (J. Moore; Bracher; Case 50–68). Confident navigator though he is, having traveled widely even before his adventures in Lilliput, Gulliver always loses his way before making landfall: driven by storm, abandoned by fellow sailors, abducted by pirates, or marooned by mutineers. The implication is that strange new lands lie everywhere, accessible by slight deviations from well-trafficked sea lanes. These enclaves are disconnected on both sides, at least until Gulliver penetrates unknown waters and makes his discoveries. The Lilliputians, Brobdingnagians, Laputans, and Houyhnhnms are sheltered from the rest of the world; they are as surprised to see Gulliver as he is to see them. For an intentional version of such isolation, there was a real-life model in Japan, which is oddly included in the otherwise fantastic geography of part 3. As Robert Markley has argued, “Swift contrasts the corruption of contemporary England to the imagined ideality that refuses commercial and imperial adventurism” (Far East 264). The decidedly less imposing Lilliputians enjoin Gulliver to survey the circumference of their dominions, yet the Emperor is somehow lauded as the “sole Monarch of the entire World”; the emperor of Blefusco is said to have “justly filled the whole World with Admiration” (11:53, 54). How eagerly these tiny creatures overestimate their knowledge and power; how similar they are to English and French patriots. Gulliver has his own pretensions, using but also emending Herman Moll’s maps to accommodate each of his discoveries, including Houyhnhnmland, within otherwise blank or uncertain spaces in the South Seas (fig. 5).

Swift renders these worlds with a plenitude of detail, delineating them as quasi-virtual realities. Ironically, the editor claims to have struck out “innumerable Passages” on winds, tides, and compass variations, and Gulliver insists he will not trouble us with overparticularity. He promises instead separate publications, including a book on Lilliput “containing a general Description of this Empire, from its first Erection, through a long Series of Princes, with a particular Account of their Wars and Politics, Laws, Learning, and Religion; their Plants and Animals, their peculiar Manners and Customs, with other Matters very curious and useful” (11:10, 47). It is another jest, since the four sections are already stuffed with detail. We get patient accounts of cultural traditions and political structures, expositions that move panoramically from governing bodies to families to individuals. We get anatomies of grotesque bodies and stories of horses threading needles, milking cows, and using hammers and axes. Indeed, it is at these moments that Gulliver’s Travels most vividly recalls contemporary French utopias such as Denis Veiras’s History of the Sevarites (1675), Gabriel de Foigny’s La terre australe connue (1676), and Simon Tyssot de Patot’s Voyages et avantures de Jacques Massé (1710), all of them test cases for the limits of imaginative geography. There are seeds, additionally, for Robert Paltock’s Life and Adventures of Peter Wilkins (1750), with its underground world, Saas Doorpt Swangeanti, and its people with retractable wings. Traditionally, Gulliver’s Travels is seen as an antirealist satire, a parody of more empirical genres, such as the emergent novel, but the thickness of its descriptions can numb our skepticism and immerse us in its counterfactual environments.4 Gulliver describes only places that do not exist, piling up details about, say, Brobdingnag but telling us almost nothing about his home in Redriff—and we learn nothing at all about his subsequent home in Notinghamshire. The inversion is easy to miss, but it gives a strange tangibility to patently imaginative constructs, reducing familiar places in England to a kind of skeletal inconspicuousness. Oddly, moreover, Swift lets Gulliver bring back material evidence, apparent proof that all the faraway lands are real, that they are ontologically connected to our own world. The various languages are as alien as anything. Their densely grouped consonants and overabundance of syllables sit uncomfortably on the English tongue, but they fill the pages. As Srinivas Aravamudan suggests, “exoticism” might be too trivializing a term to contain such joyful strangeness—better, perhaps, is “xenophilia.”5

5. Map of Houyhnhnmland, in the vaguely outlined vicinity of present-day Australia and Tasmania. COURTESY OF THE BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, YALE UNIVERSITY

The separateness of these worlds allows for their radical differences, their extrication from otherwise inescapable imperfections. The king of Brobdingnag and Gulliver’s master Houyhnhnm are among the only characters interested in England, and they respond to Gulliver’s descriptions with blistering critiques consistent with a broader resistance to external influences. Their strongest criticisms are reserved for English ambitions, military and commercial, that reach past national borders. The king of Brobdingnag rejects instruction on the technologies of modern warfare, wondering “how so impotent and groveling an Insect … could entertain such inhuman Ideas, and in so familiar a Manner” (11:134–35). He stands amazed by Europe’s “chargeable and extensive Wars” and asks “what Business we had out of our own Islands, unless upon the Score of Trade or Treaty, or to defend the Coasts with our Fleet” (11:131). The Houyhnhnms are likewise “cut off from all Commerce with other Nations,” their Spartan abstemiousness differing sharply from England’s glut of foreign luxuries—a sort of excess typically castigated as feminine or feminizing (11:273). As Gulliver states, “This whole Globe of Earth must be at least three Times gone round before one of our better Female Yahoos could get her Breakfast, or a Cup to put it in” (11:235–36).6 Both lands are geographically—and therefore politically and commercially—isolated, and this accounts for what seems at first ignorance or naïveté but is ultimately righteous purity. Thus sheltered, Houyhnhnmland reads like an inverted catalog of European corruptions: here there is no “Treachery or inconstancy” of friends, “nor the Injuries of a secret or open Enemy”; one encounters “no Occasion of bribing, flattering or pimping, to procure the Favour of any great Man or of his Minion”; one needs “no Fence against Fraud or Oppression”; there are, moreover, none of the familiar types, for instance “Gibers, Censurers, Backbiters, Pickpockets, Highwaymen, House-breakers, Attorneys, Bawds, Buffoons, Gamesters, Politicians, Wits, Spleneticks, tedious Talkers, Controvertists, Ravishers, Murderers, Robbers, Virtuosos,” not to mention “Fops, Bullies, Drunkards, strolling Whores, or Poxes” (11:276–77). The list goes on. Clearly, Swift enjoyed sifting through so many follies and pointing his finger in so many directions—or at any rate he felt compelled to do so. The Houyhnhnm language, we will remember, has no words for “lie” or “evil” or “pride.” The land’s geography serves as a sort of spatial prophylactic, sealing the inhabitants off from the contagious vices that European travelers were then spreading, alongside venereal diseases, both abroad and at home.

So many absences clear a large expanse for positive proposals, even if unironic moments are hard to find. What seems earnest is usually terse and cryptic. Proper government is trimmed down to a republican minimalism.7 The king of Brobdingnag, we are told, confines “Knowledge of governing within very narrow Bounds; to common Sense and Reason” (11:135). The Houyhnhnms, ruled by assemblies of aristocrats, enthrone reason itself, a term indistinguishable from nature, which engenders it, and virtue, which is its chief effect. Reason, to some extent, takes the place of laws themselves, since the Houyhnhnms “have no Conception how a rational Creature can be compelled, but only advised, or exhorted; because no Person can disobey Reason, without giving up his Claim to be a rational Creature” (11:280). Indeed, Swift seems more comfortable with abstract ideals, which he sprinkles liberally throughout his descriptions. The Lilliputians, with all their failings, have “more Regard to good Morals than to great Abilities”—a preference echoed in later sections (11:59). In Houyhnhnmland, “FRIENDSHIP and Benevolence are the two principal virtues,” which everyone practices universally, along with “TEMPERANCE, Industry, Exercise, and Cleanliness” (11:252, 253). Of course, Gulliver promises yet another volume on Houyhnhnmland. The specific traditions are seldom proposed for lockstep imitation, and next to More’s Utopia (1516) Gulliver’s Travels seems maximally elusive and disillusioned. Perhaps no reader can isolate a core of inarguably serious prescriptions, but these extraordinary spaces at least suggest new possibilities, or remind us of old ones, some of them no doubt attractive. Gulliver, for one, is converted. Toward the end of the novel, he affirms, “I had cured myself of some bad Habits and Dispositions, by endeavouring, as far as my inferior Nature was capable, to imitate the Houyhnhnms” (11:280).

Whatever the initial wonder, Gulliver adapts quickly to each land he visits, uncovering correspondences right under the surface and thereby familiarizing the foreign. Everything in Lilliput and Brobdingnag can be converted by the one-to-twelve or twelve-to-one ratio, all the various creatures and objects of these worlds being internally proportionate. Familiar reference points unwrap the strange exteriors of new customs and languages, revealing inside only composites of what already exists elsewhere. Thus clothing in Lilliput is somewhere between “the Asiatick and the European,” in Brobdingnag between “the Persian, and partly the Chinese” (11:14, 89). The language of the Houyhnhnms “approaches nearest to the High-Dutch or German” and “might with little Pains be resolved into an Alphabet more easily than the Chinese” (11:218, 210). Words notwithstanding, Gulliver always finds it easy enough to converse with signs, gestures, and readily comprehensible affects. Before we know it, he learns the ropes and settles into a niche, accepting and even adopting the perspectives, customs, and values of those around him. It turns out that all these distant countries are not very different at all. Among the Houyhnhnms, Gulliver goes so far as to “imitate their Gait and Gesture,” walking and talking as though he were himself a horse. They reject him eventually. In Brobdingnag, they call him a “Lusus Naturae,” a freak of nature (11:104). Famously, in “On Poetry: a Rhapsody” (1733), Swift criticized mapmakers for filling in the blank spaces of Africa with imaginary monsters. Now Gulliver is the monster—a reversal that puts monstrosity at the source of its projection.

These imaginary lands are beset with the same kinds of strife and upheaval that the rest of the world suffers. The Lilliputians have the Blefuscans to contend with, just as the English had the French. The Houyhnhnms have the Yahoos, who represent the Irish and humanity at large, including Gulliver, viewed as a potential rabble-rouser who might “seduce [other Yahoos] into the woody and mountainous Parts of the Country, and bring them in Troops by Night to destroy the Houyhnhnms Cattle” (11:263). Gulliver finds out that even the peaceful Brobdingnagians are not immune: “They have been troubled with the same Disease to which the whole Race of Mankind is Subject; the Nobility often contending for Power, the People for Liberty, and the King for absolute Dominion. All which, however happily tempered by the Laws of the Kingdom, have been sometimes violated by each of the three Parties; and have once or more occasioned Civil Wars” (11:122). We will remember, of course, how the Laputans—literally—put down their rebellions, and the strategy backfires in a subsequently published anecdote in which the Lindalinians find an ingenious way to “kill the King and all his Servants, and entirely change the Government.”8 On several occasions, Gulliver mentions England’s own Civil War, which casts a shadow over the entire narrative. More generally, Swift assumes a downward historical and evolutionary—or devolutionary—spiral. The description of Lilliput gets this important asterisk: “I would only be understood to mean the original Institutions, and not the most scandalous Corruptions into which these People are fallen by the degenerate Nature of Man” (11:60). When Gulliver calls forth illustrious figures of the past, they occasion familiar ancients-versus-moderns arguments from the Battel of the Books (1704). More gloomily, this window on history leads him to admit, “It gave me melancholy Reflections to observe how much the Race of human Kind was degenerate among us, within these Hundred Years past” (11:201). Finally, the Yahoos, we discover, are actually descendants of a Crusoe-like castaway, plus one female companion: a startling revision to the Crusoe story that now ends in not Homo economicus but Homo pravus, Homo deformis. There are qualifications to this apparent idealization of the past, which of course bore the seeds of degraded modernity, but modern degradations are of a different order of magnitude (Rawson, “Character of Swift’s Satire”). Against the decline of the present, Swift juxtaposes a primitive purity manifested partly in Brobdingnag and more fully in Houyhnhnmland. Lodged here, but also challenged in these very places, such ideals have been preserved only by the happenstance of oceans of distance.

Formally, Swift unmasks his worlds as assemblages of specific allegories and general representations of humanity, reining in the farthest corners of the globe with an expansive satiric vision. This is a critique of the veracity—but also the value itself—of travel writing, a denunciation of the genre’s mad dash for exotic particulars, which turn out to be emblems of our own flaws and failures.9 I cannot do justice here to the intricacy of Swift’s satire and mean only to claim it eschews geography as a placeholder for utopia. Over the years, the old “allegorical school” (Firth; Case 69–96), which read the narrative for its specific references, has been augmented by new political readings (Higgins, Swift’s Politics 144–98), as well as recent work on the genre of secret history (Bannet, “Secret History”; Rabb, “Secret Memoirs”). Gulliver’s Travels was, of course, followed by a series of interpretive keys, such as Edmund Curll’s in 1726, that tried to expose one-to-one correspondences, usually at the service of highly polemical agendas. In contrast, F. P. Lock’s counterallegorical position, which built on arguments by Phillip Harth and J. A. Downie (“Political Characterization”), has pushed us to see broader representations of human nature, an approach implicitly extended by studies aimed at definitions of the human, in a cultural and biological sense (Nash 103–30; L. Brown, Homeless Dogs 46–53). Far from being irreconcilable, the two approaches are sometimes hard to distinguish. The references unfold a larger picture that generally reconfirms the particulars. As Simon Varey puts it, the narrative can be viewed as analogical, rather than allegorical, such that its “generality emerges only through specific allusions” (“Exemplary History” 41–42). If the emperor of Lilliput is George I, the Lilliputians are a microcosm of humanity or an aggregate of certain common human qualities. What is important, for my purposes, is that both interpretations assume projections of the familiar onto the foreign, representations that cover over geographic difference and reduce other places to reminders of home and conjectures drawn from it, reflecting identifiable figures and events along with broader commentaries. In both cases, more travel gives us more of the same, more extrapolations of the very problems we ought to be noticing—and fixing or accepting—around us. Lock argues that “Swift and most of his contemporaries believed in the general uniformity of human nature. Forms might vary: Manners, customs, and institutions were influenced by such factors as climate and would naturally change over periods of time and vary in different places. But the essentials, the basic passions and desires of mankind, were constant” (33).

However much forms are assumed to vary, Gulliver slides almost imperceptibly into a universalizing register, intuiting truisms about humanity as a whole, truisms that apply to all the lands he visits—and, of course, to Europe. Learning of the plot against him in Lilliput, he concedes, “I had indeed heard and read enough of the Dispositions of great Princes and Ministers; but never expected to have found such terrible Effects of them in so remote a Country, governed, as I thought, by very different Maxims from those in Europe” (11:67). What he realizes is these dispositions are everywhere princes and ministers are. Bodily imperfections in Brobdingnag lead him, with what becomes characteristic misogyny, to “reflect upon the fair Skins of our English Ladies, who appear so beautiful to us, only because they are of our own Size, and their Defects not to be seen but through a magnifying Glass” (11:92–93). Even the Struldbruggs bow to the effects of age and decay, regardless of their miraculous longevity. When Gulliver learns this, he admits, “I grew heartily ashamed of the pleasing Visions I had formed; and thought no Tyrant could invent a Death into which I would not run with Pleasure from such a Life” (11:214). Traveling widely only deflates such visions. Pride, our signature vice, is unknown to the Houyhnhnms, but Gulliver, “who had more Experience, could plainly observe some Rudiments of it among the wild Yahoos” (11:296). These are bitter disenchantments, culminating in part 4 with Gulliver’s recognition, on a watery surface, that he is actually a Yahoo. Famously, Swift wrote that “SATYR is a sort of Glass, wherein Beholders do generally behold every body’s Face but their Own” (Swift, Prose Works 1:140). Not so in this case, for Gulliver has traveled halfway around the world to behold his own bestial identity. Afterward, he forces himself to “behold [his] Figure often in a Glass, and thus if possible habituate [himself] by Time to tolerate the Sight of a human Creature” (11:295). The sea, in Gulliver’s Travels, is not a portal to new worlds but a mirror on our own world.

Gulliver travels, and satire travels with him, seeming to doom utopia wherever he sets foot. Part 3 contains an extended critique of projects, including political projects—ostensibly more practical utopias.10 Many of these projects Swift derides as foolish, especially those pertaining to natural philosophy and language, but some of the ideas sound valid enough, for example the attempts at “persuading Monarchs to chuse Favourites upon the Score of their Wisdom, Capacity and Virtue … teaching Ministers to consult the publick Good … instructing Princes to know their true Interest, by placing it on the same Foundation with that of their People” (11:187). The problem is that these proposals fall on deaf ears. More successful—and barbaric—are colonial projects: “Ships are sent with the first Opportunity; the Natives are driven out or destroyed, their Princes tortured to discover their Gold; a free Licence given to all Acts of Inhumanity and Lust; the Earth reeking with the Blood of its Inhabitants” (11:294). In this vein, the king of Brobdingnag calls Europeans “the most pernicious Race of little odious Vermin that Nature ever suffered to crawl upon the Surface of the Earth,” and the Master Houyhnhnm corroborates, looking on Gulliver and humans as “a Sort of Animals to whose Share … some small Pittance of Reason had fallen, whereof we made no other Use than by its Assistance to aggravate our natural Corruptions, and to acquire new ones which Nature had not given us” (11:132, 259). According to Lord Munodi, “different Nations of the World had different Customs,” but the cascading judgments delivered in Brobdingnag and Houyhnhnmland transcend these locations, disclosing ideals that are germane everywhere but instantiated nowhere, not even in patently fantastic lands (11:175). Such condemnations have much to do with the formation of two other opposed interpretations, termed the “hard” and “soft” schools: according to the first, Swift speaks through Gulliver and intends a pessimistic critique of human nature; according to the second, Swift distances himself from Gulliver and merely satirizes frustrated idealism (Clifford, “Gulliver’s Fourth Voyage”). Significantly, neither interpretation permits the radical alterations of utopia. By the end of the novel, Gulliver, at least, falls into misanthropy, loathing the sight—and even the smell—of his fellow humans. He is, to borrow from Judith Shklar’s typology, a “self-righteous misanthrope,” the sort who hates “his contemporaries and his own immediate world, because he has some inner vision of a transformed humanity” (“Misanthropy” 194).

All-encompassing though it is, Gulliver’s Travels leaves a minimized remainder, a residue of desire that exceeds worldwide critique, exceeding also adequate explanation by any approach that assumes a full tearing down of utopian possibility. Undeniably, Swift’s vision is bleak and even brutal, and all utopias can be interpreted as authoritarian straitjackets—or worse (Orwell; Rawson, God, Gulliver, and Genocide). They are often impelled by disgust, never shedding a need for protective distance. Actually, in Gulliver’s Travels, Gulliver needs distance even within utopian spaces themselves. The novel abounds in small enclaves, disconnected spaces within disconnected spaces that are in some ways preferable to the utopian worlds around them: the converted temple in Lilliput, the portable box in Brobdingnag, the freestanding room next to the Houyhnhnm abode. These spaces limit social access and foster one-on-one relationships. Thus Houyhnhnmland is a utopian space with a utopian subspace inside it, and the latter, however undefined, withstands more robustly the failings of whole societies. Gulliver, under the protection of his master, reforms to a surprising degree, and his master eventually learns the meanings of “lie” and “evil.” They come to a flexible, if ultimately unequal, understanding and build a friendship that seems at once ideal and feasible—ignoring, for a moment, the overt fictionality of a talking horse. By the end, the sphere narrows until all that is left is a utopian disposition that can contract no more and can, in fact, only expand into larger spheres of interaction—if never quite to the dimensions of a South Seas island. Gulliver trots as a Houyhnhnm, but really he is a Trojan horse, returning to England with an adversarial utopia inside himself.

Gulliver’s Travels, then, converts its utopian geography into utopian subjectivity. That its spaces can be mobilized is clear enough from the lingering effects they produce whenever Gulliver departs for home. Each time, he undergoes a difficult and ultimately incomplete reacclimation, carrying traces of his newly acquired perspectives back to England. After leaving Brobdingnag, when a group of sailors surround him, he claims to have been “confounded at the Sight of so many Pigmies; for such I took them to be, after having so long accustomed mine Eyes to the monstrous Objects I had left” (11:143). He snaps out of it, but the trauma recurs in greater measure after he leaves Houyhnhnmland and encounters a talking human: “I thought I never heard or saw any thing so unnatural; for it appeared to me as monstrous as if a Dog or a Cow should speak in England, or a Yahoo in Houyhnhnmland” (11:286). Symptoms of madness display the distance between Gulliver’s thoughts and the thoughts of those around him, and the sign of utopia becomes unsociable eccentricity. This time, the returned traveler remains changed, unable to reintegrate, or reintegrate completely, even with his own family. They invade his senses, their sight filling him with “Hatred, Disgust and Contempt,” their smell nauseating him so that he says, “I always keep my Nose well stopt with Rue, Lavender or Tobacco-Leaves” (11:289, 295). Thus Gulliver builds a wall around himself, insulating his mind and body, much as each of the imaginary lands was separated by unnavigable seas. He re-creates Houyhnhnmland as an internal state, an imaginary space to which he can return at will: “My Memory and Imaginations were perpetually filled with the Virtues and Ideas of those exalted Houyhnhnms” (11:289). His plan, he says, is “to enjoy my own Speculations in my little Garden at Redriff; to apply those Lessons I learned” (11:295). By removing the foregoing utopias to memory, the imagination, and speculations, Swift at once diminishes them and puts them on a firmer foundation. Gulliver complains that some readers have thought his book “a meer Fiction out of mine own Brain; and have gone so far as to drop Hints, that the Houyhnhnms and Yahoos have no more Existence than the Inhabitants of Utopia” (11:8). Whether or not the Houyhnhnms exist only in Gulliver’s brain, they at least exist there as imperishable ideals. John Traugott has remarked, “To the choices of life—to be a fool or a knave, or to retire from the human race to Utopia or Houyhnhnmland—More and Swift propose a third: one can live in the world by playing the fool and not being one, by keeping utopia a city of the mind, where Raphael Nonsense and Lemuel Gulliver can live” (564). Actually, Gulliver models this choice himself, showing us what it might look like not only to maintain a utopia of the mind but also to make it a lived practice. This utopia is an embodied subjectivity, wired to all the senses and directing—even necessitating—specific responses and actions. The internalized Houyhnhnmland makes Gulliver sneer in disgust and reel back in horror, but his moral reformation is thereby preserved, guaranteed against others’ influences. He becomes implausibly autonomous, though his life is never so implausible as the preceding geographies. Gulliver concedes that “some corruptions of my Yahoo Nature have revived in me by Conversing with a few of your Species, and particularly those of mine own Family, by an unavoidable Necessity” (11:8). Indeed, he disavows the species but cannot really get away from family.

This utopian interiority gradually extends outward and materializes in the stable and in the new bond with horses. As Gulliver tells us, “The first Money I laid out was to buy two young Stone-Horses, which I keep in a good Stable, and next to them the Groom is my greatest Favourite; for I feel my Spirits revived by the Smell he contracts in the Stable. My Horses understand me tolerably well; I converse with them at least four Hours every Day. They are Strangers to Bridle or Saddle; they live in great Amity with me, and Friendship to each other” (11:290). At home in Redriff, or rather next to his home in Redriff, Gulliver creates a microcosm of Houyhnhnmland, modified by—and modifying—the realities of the space that encompasses him. His love of horses, silly as it sounds, has received serious attention. James Gill describes Gulliver’s relationship with them as an outgrowth of traditional “theriophily,” “the belief that animal life provides man with an exemplary pattern of conduct,” a pattern that “subsumes primitivistic beliefs both in the immanence of nature and in the almost infinite capacity of man to degenerate in an enervating human society” (533–34). The argument has been elaborated in a number of directions.11 My own reading draws on that of Ann Cline Kelly, who looks at the bonds between pets and pet owners throughout Gulliver’s Travels and demonstrates that these bonds surpass societal binaries and thereby create what she calls “an intimate utopian bubble” (332). Utopia, for Swift, entailed rigid, if understated, hierarchy. It could not compass a population of equals dispersed across a landscape; it could, however, connect individuals whose relative status or power was unquestionable. Pet keeping is a useful analogy because it establishes these roles more unquestionably than any political theory. Throughout his travels, Gulliver lingers in the aforementioned miniature utopias, places within places that stand at one remove farther than what is already a disconnected retreat. Such enclaves within enclaves foster intimate relationships that always seem preferable to affiliations with larger groups, be they Lilliputians or humans. In the stable, among his horses, Gulliver re-creates this sort of space. Now he is master, but he nevertheless endeavors “to apply those excellent Lessons of Virtue which I learned among the Houyhnhnms” and “to treat their Persons with Respect, for the sake of my noble Master, his Family, his Friends, and the whole Houyhnhnm Race” (11:295).

Cautiously, the utopian circle encompasses like-minded humans, too. As soon as he leaves Houyhnhnmland, Gulliver is rescued by Pedro de Mendez, “a very courteous and generous Person” who is very different from the depraved Yahoos (11:286). At first, Gulliver considers suicide, but the captain intercedes, and Gulliver admits that Mendez “spoke so movingly, that at last I descended to treat him like an Animal which had some little portion of Reason,” which is of course how the Houyhnhnms had treated him (11:287). Gulliver calls Mendez “a wise Man” and affirms, with some surprise, that “his whole Deportment was so obliging, added to very good human Understanding, that I really began to tolerate his Company” (11:288). Mendez pushes Gulliver to return home, saying that “it was altogether impossible to find such a solitary Island as I had desired to live in” (11:289). Alternatively, Gulliver realizes, “I might command in my own House, and pass my time in a Manner as recluse as I pleased” (11:289). The plan is not to live totally isolated but to secure a position from which to limit social engagements and dictate their nature. In correspondence with Pope, Swift himself claimed, “I have ever hated all Nations professions and Communityes and all my love is towards individuals…. I hate and detest that animal called man, although I hartily love John, Peter, Thomas and so forth” (Correspondence 3:103).12 Along these lines, Helen Deutsch has shown how figurations of friendship in Swift’s verse could compensate for the failure of larger-scale social ideals. Gulliver, in the last sentence of the novel, states that pride, as a character flaw, is the great exclusionary criterion of his fellowship with others: “I here entreat those who have any Tincture of this absurd Vice, that they will not presume to appear in my Sight” (11:296). Among those he does not shut out, he makes no promises of civility, much less intimacy. He barely tolerates his family, with the intention of reforming them, and remains a square peg incongruent with the circular hole around him. “My Friends,” he says, reminding us he has friends, “often tell me in a blunt Way, that I trot like a Horse; which, however, I take for a great Compliment: Neither shall I disown, that in speaking I am apt to fall into the Voice and manner of the Houyhnhnms, and hear my self ridiculed on that Account without the least Mortification” (11:279). Indeed, he both ignores and confronts others, and the book itself is intended for our “Amendment,” not our “Approbation” (11:8). Swift put it more belligerently in the letter to Pope, asserting he wanted “to vex the world rather then divert it” (3:102). After six months, however, the target audience remained unrepentant, and Gulliver claims to be “done with all such visionary Schemes for ever” (11:8). That may be so, but all he is sacrificing is the hope of reforming England as a whole, an impossible goal for any utopist. Swift picked his battles, and he has been noted for his localized and activist zeal (Said, “Swift as Intellectual”). One critic has gone so far as to argue that he was “more concerned about the abuse of revolution than about revolution itself,” which he left room to support under the right circumstances (Herron 670). Gulliver, for his part, never rules out visionary schemes within reduced spheres of activity.

We cannot know the ironic distance between Swift and Gulliver, but certainly they shared a sense of isolation and alienation. Swift was famously unhappy in Ireland, but he did not feel at home in England either. He argued passionately and successfully on behalf of the Irish, especially in economic matters (S. Moore), but this does not change “the ambivalent nature of his patriotism” (Mahony 4). As Carole Fabricant observes, “It is not surprising … that Swift wound up creating the ultimate ‘stranger in a strange land,’ Gulliver—a man who is by definition an alien wherever he goes, and who is incapable of reclaiming a sense of home even when he returns to England” (“Colonial Sublimities” 311). In an earlier study, Fabricant explored these sentiments exhaustively, showing how Swift’s experience of isolation differed significantly from the experiences of like-minded friends. Pope, for instance, had his idyllic retreat at the Twickenham villa; Henry St. John, First Viscount Bolingbroke waxed indulgently about buying Bermuda and spending his remaining days there (Fabricant, Swift’s Landscape 4). Swift was more skeptical, temperamentally averse to such daydreams. Biographically, it seems appropriate that he has Gulliver transmute utopian geographies into a utopian interiority, uprooting Bermudan idealizations and reimagining them around a single individual, or a small group, wherever that happened to be. He might have taken similar consolation himself.

Such compensatory spaces lie outside the rubric of the pastoral and the domestic, terms that look backward and forward, respectively; they also lie outside strict conceptions of utopia. Gulliver’s utopia is forged in the crucible of almost overpowering misanthropy, a feeling that renders utopia an escape from humanity. This utopia is at first distant, on a far-off horizon, retreating as he advances, but it becomes something more attainable, something more like desire and the wherewithal to act on it. Utopia, thus diminished, is relocated to the here and now, on the narrow patch of ground under Gulliver’s hoof-like feet.