two

FICTION

Juan Ortiz surveyed the low coastline beyond the port bow from the helm of a three-masted caravel. Twelve other men stood ready at the sails and anchor. The waters of what would be called Biscayne Bay were cloudy as the tannin-laced runoff from the mangrove fringe intermixed with the crystalline bay. Ortiz searched for a break in the twisted fortress of mangrove, a hint of solid ground that would lead to the interior and the prizes he sought.

Ortiz was on the cutting edge of the enormous surprise delivered to the Spanish crown by Columbus and his followers. Not yet a decade had passed between Columbus’s first voyage and Ortiz’s foray to what we know as Florida. While Columbus found glory and immortality, Ortiz was seeking a more tangible reward—slaves.

The wall of green and brown showed a momentary interruption of blue-green, revealing the mouth of a river or large stream. Ortiz ordered the sails struck. As the caravel coasted to a stop, he ordered the anchor dropped. Without a further word, the sailors unshipped and lowered a longboat into the calm water.

The men immediately switched roles from sailors to soldiers. From the caravel’s hold, they passed up their meager inventory of armor, swords, pikes and a pair of arquebuses. Slow-match fuses were lit with flint and steel, and six men plus Ortiz carefully climbed into the longboat. The remaining crew handed down heavy bags, before settling in to guard the ship in their absence.

The whirlwind Spanish conquest of Cuba presented an unprecedented problem. Great labor was required to exploit the new possession, but few Spaniards were willing to do the work. Nearly every Spaniard dreamed of seizing wealth in the New World and had little desire to hew stones, build forts or till fields.

The indigenous peoples were enslaved quickly by the Spanish with their steel weapons, horses and war dogs. The Indians were defenseless against infectious diseases introduced by the Spanish and died in droves. With their hunter-fisher-gatherer economies destroyed, malnutrition and cultural dislocation further undermined their stamina. The Spanish demanded more and more slaves, opening opportunities for adventurous men like Juan Ortiz.

As the crew rowed for shore, Ortiz was alert for ambush. He knew he wasn’t the only slaver working this coast. The easiest and largest captures were made from villages that had never seen a Spaniard. But a few Indians always escaped to spread the word of a new predator who came from the sea and devoured entire families, taking them away never to be seen again.

Slowly the river mouth opened. Ortiz recognized the area would be ideal for a settlement, with dry land visible on one side and easy access to fishing in the bay. The crew remained quiet, carefully tending their oars to prevent unnecessary noise. Birds flitted overhead, including the occasional scarlet flash of a cardinal.

As the river’s course turned south, a village was revealed. Peaked roofs thatched with palmetto fronds rose above pilings sunk at the river’s edge. Dugout canoes were beached underneath. A thin tendril of smoke rose almost straight up into the bright midday sky of April 4, 1498.

A sudden shout pierced the air. The Spanish were spotted. Ortiz steered directly for the huts and urged his men to pull hard on their oars. The longboat sped over the water. Ashore, the noise grew louder, as women grabbed children and cried their alarm. Clearly they feared the men with the shiny hats.

This Spanish recreation of a caravel (supposedly Columbus’s Santa Maria) was built in the late nineteenth century. It was sailed to the United States for display at either the World’s Columbian Exposition or the Columbian Naval Review. It is representative of the ships discovering and exploiting the New World in the sixteenth century. Note the high “castles” fore and aft. 1893 photograph on glass by Edward H. Hart, Courtesy Library of Congress.

The longboat scrunched on the sandy beach and the men stepped ashore. One arquebusier remained behind with the boat, while Ortiz and five other Spaniards walked slowly into the village. Children huddled behind their mothers, but no one ran for the palmetto scrub. Ortiz realized this village had never been raided before. Otherwise the Indians would have fled. Using the flat of his sword, he herded the villagers back toward the longboat.

The arquebusier opened one of the heavy bags and removed coffles to link the women together to prevent their escape. The men would return in a day or two and be captured as well. In the meantime, the Spanish would have their sport with the women. Ortiz estimated this raid would capture perhaps fifty slaves, and after a quick trip back to Havana, he would return to this coast in search of more.

FACT

Juan Ponce de León is credited with discovering Florida in 1513. Long before his voyage of discovery, the Spanish undoubtedly visited the peninsula in search of gold (there was none) and slaves (there were many). It is likely Ponce’s legendary navigator knew much more about the waters around Florida than is acknowledged in the official history books. He certainly was a lucky man who “discovered” the nautical essentials required to travel from Cuba to both coasts of Florida and return. Ponce’s “voyage of discovery” was very much a cakewalk.

Both Ponce and his navigator—Antón de Alaminos de Palos—accompanied Columbus on at least one of his voyages of discovery. It is likely they met on Columbus’s second voyage (1493–1496), among the 1,200 people aboard seventeen ships. It was a very eventful trip.

On the first voyage, Columbus traveled through the modern Bahamas to reach the eastern side of Cuba and return via Hispaniola. On his second trip (with Ponce and Alaminos), Columbus sailed farther south, crossing through the Antilles to discover Puerto Rico, the southern shore of Cuba and Jamaica, before turning back to Hispaniola and eventually returning to Spain. On the trip, Columbus captured 1,400 slaves, bringing 300 back to Spain. But enslaving Indians was against royal policy and the Crown ordered them freed and returned to America.

The royal command was followed on Columbus’s third voyage (1498–1500), but Spaniards in the New World continued to capture and use Native Americans as slaves. Columbus himself, in his logbook, noted the use of Indian slaves for sex. In 1501 slavery in the New World was made legal by royal decree.

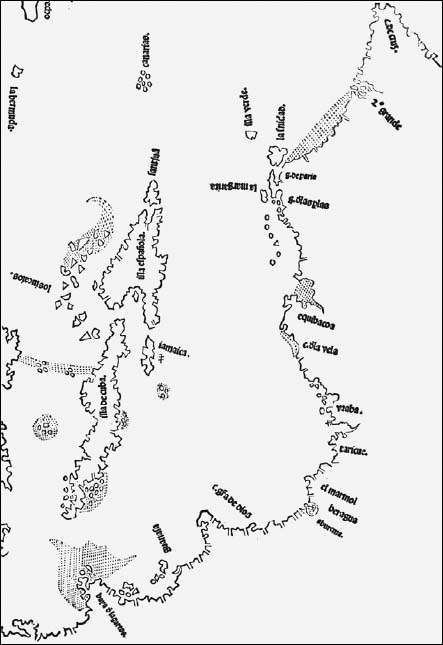

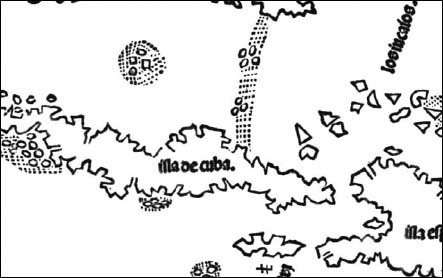

This 1511 map was drawn by Andrés de Morales two years before the “discovery” of Florida by Ponce de León. Both “illa de cuba” and “illa española” are easily recognized. North is to the left. Columbus explored Central America south of the Yucatán on his fourth and final voyage between 1502 and 1504. The map comes from Pietro Martire d’Anghiera’s book Impressum Hispali published by Jacobum Corumberger in April 1511. Courtesy of the John Work Garrett Library of the Johns Hopkins University.

Ponce came back to the New World in 1506 at the age of forty-six to lead the conquest of Puerto Rico. He was appointed governor in 1509. For his work in the subjugation of the indigenous peoples and his early colonization efforts, Juan Ponce was commended by Charles V, King of Spain. While in Puerto Rico, Ponce heard rumors of a land north of Cuba called “Beimeni.” The rumors were so persistent that “Beimeni” was mapped before it was “discovered.”

An Italian priest in service to the Crown, Pietro Martire d’Anghiera, included it on his 1511 book. He labeled a landmass north of Cuba as “Isla de beimeni parte.” In 1512 Ponce petitioned the Crown to seek this mysterious land. Charles agreed.

Ponce returned to Puerto Rico and arranged his expedition. A key participant was Alaminos, about whose activities between 1496 and 1513 we know little or nothing. We do know on March 3, 1513, he left Puerto Rico with Ponce and three ships to set sail into the history books.

Alaminos guided the expedition’s three ships east of the treacherous Bahamian waters to arrive offshore of Florida on March 27. This was either good luck or the first indication of Alaminos’s prior knowledge of the area. Modern navigators using current charts think of this route as an easy, full-sail passage to Florida.

It is important to remember the nature of the ships sailed by the Spanish nearly five centuries ago. They were designed for medieval-style naval warfare, with high “castles” fore and aft so soldiers could enjoy “high ground” while fighting against boarders. The cannon-against-cannon style of naval warfare was a century in the future. The ships also carried at least eight feet of draft, making exploration close to an unknown shore very risky. Once aground, the wooden ships were fragile and their loss would strand the crew on a hostile shore far from home.

Alaminos’s second bit of good luck occurred near Lake Worth inlet (modern Palm Beach) where the expedition encountered the effects of the furious Gulf Stream. As Ponce records, even with full sails, his ships were swept backward by the current. Ponce called the area Cabo de Corrientes, the Cape of Currents, although we know now it is not a cape. Alaminos defeated the Gulf Stream with a counterintuitive strategy by sailing very close to shore, an always risky tactic with fragile, deep-draft vessels.

The effects of currents on ships are almost impossible to calculate when a ship is beyond the sight of land. Without a point of reference, the ship can seem to be moving ahead (sails pulling, bow wave splashing) while in reality it is stopped or even moving backward. Alaminos’s “discovery” of the Gulf Stream and then a tactic to defeat it is either the mark of a fine navigator or a man with prior experience.

Alaminos’s finding was important, because it opened the door to two-way trips between Cuba and Florida. If Spanish ships could not sail against the current, any trip north from Havana would be one-way—to Spain. By sailing close inshore, Alaminos either pioneered the route south or was following a well-worn path forged by Spanish slavers over the previous decade. As Alaminos was an “old salt” in American waters by this time, it is likely he knew of this trick, either from slavers or from his own slaving voyages.

The expedition continued south. Ponce went ashore on several occasions and was often met with hostile Indians. This is another argument that Native Americans had reason to suspect the motives of the men from the sea. Surprisingly, one captured Indian understood some Spanish, according to a written account of the voyage by Antonio de Herrera. And that, of course, appears to be conclusive proof that Ponce was not the first Spaniard to reach Florida.

Alaminos’s exceptional luck continued as the expedition resumed its southward and then southwestward voyage. To this day, coral heads rise up suddenly to rip the hull of unwary sailors in the Florida Keys. On Pietro Martire’s map, the Florida Keys are clearly visible. But Alaminos stayed away from them, sailing past Key West and the Marquesas before turning north through the Rebecca Shoals passage to search for the southwestern coast of the peninsula.

D’Anghiera’s dots and small circles north of Cuba foreshadow the discovery of the reefs, shallows and islands of the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas. These few lines of ancient ink seem to indicate knowledge of Florida before the arrival of Ponce two years later. Courtesy of the John Work Garrett Library of the Johns Hopkins University.

The Spanish later named the Florida Keys “the Martyrs” because so many ships were wrecked on the reefs lying offshore of the islands. Perhaps Alaminos already knew of “the Martyrs” and the Rebecca Shoals passage, or maybe his good luck and sharp senses were responsible for his cautious route.

Alaminos took the intact fleet all the way to San Carlos Bay near Sanibel Island, where he and Ponce found what they thought was a sheltered anchorage. They were attacked there by Calusa Indians in canoes and catamarans made from dugouts. One European was killed and Ponce named the island “Matanzas,” meaning “slaughter.” After nine days, they hauled anchor and turned south to return to Puerto Rico, but not before Alaminos also “discovered” the Dry Tortugas.

This was a remarkable voyage. Florida is very low-lying, especially its Keys and barrier islands. For Alaminos to guide three deep-draft, cranky-sailing wooden ships for six months through a myriad of uncharted dangers without loss is exceptional navigation. Ponce and Alaminos not only “discovered” Florida, but also the Keys with their deadly reefs, the Rebecca Shoals passage, the San Carlos anchorage and the Dry Tortugas. Quite a feat, unless Alaminos (and perhaps Ponce too) were privy to the “local knowledge” earned by earlier slaving expeditions to Florida.

After return to Spain to present his discoveries, Ponce was assigned the chore of pacifying the cannibal Carib Indians in the Caribbean. He would not return to Florida for seven years.

In 1517, Alaminos navigated another expedition, discovering the Yucatán peninsula of Mexico. It has been suggested this voyage was a slaving expedition, although others doubt it. In any case, the Spaniards received another “hot reception,” this time from the Mayans. After a short military engagement, the Spanish withdrew and sailed along the coast looking for fresh water but were confronted by hostiles at every stop. They did, however, glimpse the gold of Central America.

In desperation, Alaminos sailed from the Yucatán back to San Carlos Bay near Sanibel, where the Calusa attacked again. During a skirmish while filling water casks ashore, Alaminos was wounded in the neck by an arrow but survived. The expedition returned to Havana.

The New World was full of such adventuresome young men. Hernán Cortés arrived in 1503 at the age of eighteen. In 1519 Cortés landed in modern-day Veracruz, burnt all of his ships—except the one commanded by Alaminos—and went forward to topple the Aztec empire. Later that year Cortés packed the looted Aztec booty and loaded it aboard the first treasure fleet to Spain. It was commanded by Alaminos, who rode the mighty Gulf Stream two-thirds of the distance to Europe. Alaminos then disappears from the pages of history after a quarter-century of New World navigation.

This is a whimsical woodcut of Ponce de Léon made centuries after his death. The legend of his search for a youth-giving fountain spread far beyond his credit as Florida’s discoverer and lures people to the Sunshine State even today. There are at least three “fountains” in the state claiming to offer Ponce’s elixir of everlasting life, all of them far from his real route of travel. Courtesy Library of Congress.

When Columbus first confronted the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, he reported their peaceful nature. Three decades later, the Spanish faced hostility everywhere they landed. It is likely the real “discovery” of the Gulf of Mexico littoral—including Florida—was conducted by Spanish slave-collecting expeditions in violation of Spanish royal policy. The smuggling of Indian slaves was Florida’s first industry and Antón de Alaminos was almost certainly one of its pioneers.

THE CUBAN CONNECTION

With slavery legalized in both the Spanish and British colonies, the legitimacy of trafficking in human beings eliminated the need to smuggle them. More than 250 years later, after the American Revolution, opinions about the morality of slavery were divided. In one of the many compromises that resulted in the U.S. Constitution in 1787, the importation of slaves was allowed until 1808. On January 1 of that year—after three centuries—the import of slaves into the United States became illegal. Making importation illegal, of course, created a smuggler’s market for slaves.

Anthony Pizzo, in his genealogy-filled book Tampa Town 1824–1886, writes of an expatriate Frenchman who came to Florida and became a mighty entrepreneur and occasional smuggler. Count Odet Phillippe, a great-nephew of King Louis XIV, arrived in Tampa in 1823 as a refugee. “In Tampa, he built houses, opened a billiard hall, ran a bowling alley and an oyster shop and did a brisk trade in cattle, horses and hogs. He bought and sold slaves, probably smuggling them in from Cuba, and shipping them north in long chained coffles for the markets of Georgia, as overseas and overland smuggling became an important trade after the United States put the Embargo on foreign slave trading,” Pizzo wrote.

Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807 and fined British captains £100 for each slave they were transporting. The Royal Navy began an aggressive naval campaign to apprehend slaving ships at sea. To avoid the fine, slavers would toss their cargo into the sea if they risked capture by the Royal Navy, creating lethal consequences for the British policy. Slavery itself was abolished by Parliament throughout the British Empire in 1833, but slaves continued to be smuggled into Florida until the outbreak of the Civil War.

The capture of the bark Wildfire in 1860 provides an insight into the industry. It was built in 1852 as part of the great wave of shipbuilding created by the California gold rush. Although a “clipper” in design, Wildfire carried square sails only on the first two masts and was thus categorized as a “bark.” It was fast and went into Mediterranean service (where it set a speed record for the crossing to Gibraltar from Boston). Wildfire was later put in service on the New York–Veracruz, Mexico run.

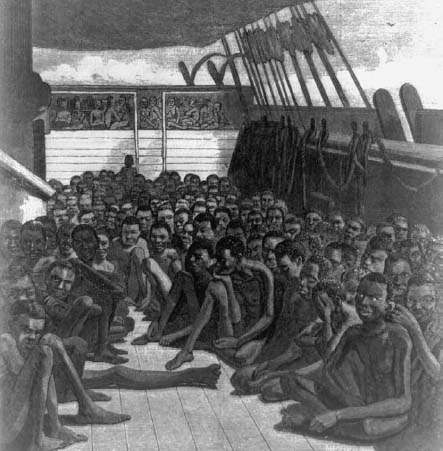

Even after importation of slaves into the United States was abolished in 1808, the trafficking in human beings did not stop. The Wildfire was captured by the U.S. Navy in 1860, probably bound for Cuba. This image of the freed slaves still aboard in Key West harbor gives an idea of the crowding aboard slavers. Several modern artists used this engraving as a model to demonstrate the horrors of the slave trade. Engraving from Harper’s Weekly, June 2, 1860. Courtesy the Library of Congress.

The American shipping industry overbuilt for the gold rush, and soon shipping rates plummeted, as did the cost of used cargo vessels. In 1859, Wildfire was purchased by Pierre Lepage Pearce. The sugar industry in Cuba at the time was in a state of expansion. Sugar prices were high and slaves were in short supply. The British antislavery patrols were putting a crimp in distribution from West Africa, so the trade was even more lucrative. The combination of circumstances—high demand, restricted supply, cheap transport and government prohibition—was perfect for smuggling. Pearce put his fast-but-inexpensive bark to work as a slaver. Wildfire picked up 615 Africans near the Congo River and sailed for Havana.

Wildfire was intercepted on April 26, 1860, by the U.S. Navy steamer Mohawk. The crew was arrested, and Wildfire was sailed to Key West, arriving in early May. Only 507 Africans survived the trip. The ship was condemned and sold for $6,500. The ship’s captain—Phillip Stanhope—and crew were charged, but a Key West grand jury failed to indict them and they walked away.

Wildfire was not the only slaver captured that spring. On May 12, the bark William was towed into Key West with 513 Africans aboard (of the original “cargo” of 744), and the bark Bogata was sailed into Key West on May 25, 1860, with 411 Africans aboard. The captains and crews were arrested but never found guilty.

Thus in one month, the U.S. Navy brought three slavers into Key West carrying more than 1,400 enslaved Africans. While purely a coincidence, it is interesting to note the number is the same as the number of enslaved Native Americans Columbus captured on his third voyage, more than three centuries earlier. Slavery was abolished in Cuba in 1888. Ten years later, Spain lost Cuba in the Spanish-American War.

SMUGGLING FOR FREEDOM

A kind of “reverse smuggling” occurred during the Civil War, as escaped slaves attempted to find freedom. Early in the war, a group of escaped slaves appeared at Fort Monroe, Virginia, and the commander admitted them. When the slave owner appeared and demanded their return under the Fugitive Slave Act, he was told the secession of Virginia meant Federal law no longer applied in the Confederacy.

The fort’s commander, Benjamin Butler, reported to the secretary of war on July 30, 1861, and referred to the escaped slaves as “contraband of war.” The name stuck. Although the “Contraband Doctrine” was never officially adopted, the idea and the term became widely applied. During the Civil War, nearly a quarter-million escaped slaves worked for the Federal government.

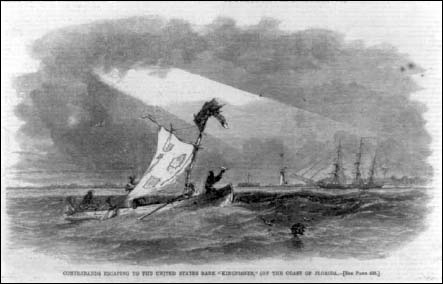

Not all the slaves escaped on foot. Some “contrabands” sailed patchwork boats out from the coastline in search of blockading Federal vessels. The Union navy secretary gave instructions to his captains to accept these self-smugglers, and if possible put them to work.

This was printed December 14, 1861 in Harper’s Weekly: “We give the following extracts from the Report of the Secretary of the Navy:”

After the Union imposed a blockade against the Confederacy, escaped slaves took to the sea in makeshift craft in search of freedom. This wood engraving foreshadows the Cuban “rafters” more than a century later who risked their lives in crude contraptions in search of liberty. U.S. armed forces also rescued thousands of them. Wood engraving from Harper’s Weekly, June 12, 1862. Courtesy Library of Congress.

EMPLOYMENT OF FUGITIVES.

In the coastwise and blockading duties of the navy it has been not unfrequent that fugitives from insurrectionary places have sought our ships for refuge and protection, and our naval commanders have applied to me for instruction as to the proper disposition which should be made of such refugees. My answer has been that, if insurgents, they should be handed over to the custody of the Government; but if, on the contrary, they were free from any voluntary participation in the rebellion and sought the shelter and protection of our flag, then they should be cared for and employed in some useful manner and might be enlisted to serve on our public vessels or in our Navy-yards, receiving wages for their labor. If such employment could not be furnished to all by the navy, they might be referred to the army, and if no employment could be found for them in the public service they should be allowed to proceed freely and peaceably without restraint to seek a livelihood in any loyal portion of the country. This I have considered to be the whole required duty, in the premises, of our naval officers.

An illustration in a later edition of the magazine gives an impression of the courage required to be a “contraband” at sea and foreshadows experiences a century later as others took to the seas in homemade boats bound for Florida in the attempt to smuggle themselves to freedom.

THE $12 BILLION RACKET

The American Civil War put an end to slavery in the United States. In 1880 most immigration restrictions were eliminated. Millions of people from all over the world came to the United States legally. With immigration open, no profitable reason existed to smuggle humans into Florida. But with the reintroduction of immigration restrictions in 1921, the smuggling of people would reappear in what authorities today call “human trafficking” and “alien smuggling.” Today it is a major industry and Florida is a full participant.

“I would like to begin by providing an important clarification and necessary distinction between the terms alien smuggling and human trafficking,” testified Charles Demore, interim assistant director of investigations, Department for Homeland Security on July 25, 2003, before a U.S. Senate committee. “Alien smuggling and human trafficking, while sharing certain elements and attributes and overlapping in some cases, are distinctively different offenses. Human trafficking—specifically what U.S. law defines as ‘severe forms of trafficking in persons’—involves (unless the victims are minors trafficked into sexual exploitation) force, fraud or coercion and occurs for the purpose of forced labor or commercial sexual exploitation.

“Alien smuggling is an enterprise that produces short-term profits resulting from one-time fees paid by or on the behalf of migrants smuggled,” Demore told Congress. “Trafficking enterprises rely on forced labor or commercial sexual exploitation of the victim to produce profits over the long-term and the short-term,” he said. “Human smuggling has become a lucrative international criminal enterprise and continues to grow in the United States. This trade generates an enormous amount of money—globally, an estimated $9.5 billion per year.”

Demore’s estimate of the global market in human smuggling was topped by an intelligence estimate created in 2001 but not declassified until 2005. National Intelligence Estimate 2002-02D was the result of an examination of the problem by all United States intelligence agencies—military and civilian. It said, “Alien smuggling is now a $10 billion to $12 billion-a-year growth industry for migrant-smuggling groups that entails the transport of more than 50 percent of illegal immigrants globally, often with the help of corrupt government officials, according to International Labor Organization (ILO) and other estimates.”

FEET DRY, BACKS WET

True to its history, today’s Florida fully participates in the smuggling of humans. It should be no surprise that the largest number of aliens being smuggled into Florida today are Cuban. The primary reason is a change in immigration law. Come-as-you-are Cuban immigrants long enjoyed a unique status under American law and were granted immediate asylum whether apprehended at sea or on shore. Hundreds of thousands of Cubans fled the island after the 1959 revolution; over a decade, the entire demographic of Miami changed. But blanket asylum was changed by the Clinton administration in 1995 to a “foot-wet, foot-dry” policy.

Cuban immigrants apprehended ashore still enjoy asylum, but if captured before reaching shore they will be repatriated back to Cuba. The new policy is part of an agreement brokered between the United States and Cuba to control illegal departures. Any Cuban “rafter” picked up in the straits of Florida now goes back to Cuba.

The legal change opened up an entirely new venue for professional smugglers, as Mireya Navarro reported on December 29, 1998, in the New York Times:

Federal officials said some of the alien smugglers, who sometimes also use the Bahamas by having their human cargo dropped off there by larger boats for pickup by a speedboat, use drug trafficking methods because they often smuggle drugs too. Of 21 pending federal prosecutions of alien smugglers in South Florida, [Border Patrol Spokesman Keith] Roberts said, at least six cases involve defendants also connected to drug trafficking.

Navarro wrote the illegal aliens each pay between $1,500 and $8,000 for the ninety-mile trip between Cuba and the Florida Keys. The ride can be perilous. In April 1998, a speedboat carrying twenty-one Cubans capsized and fourteen drowned.

Demore told Congress in 2003, “In December 2001, a capsized vessel was found in the Florida Straits, alleged to have been carrying 41 Cuban nationals, including women and children. All are believed to have perished at sea.”

The U.S. Coast Guard has the primary responsibility of keeping the aliens’ feet “wet,” intercepting them before they reach shore. The pace can be frantic, as evidenced by the activity around Thanksgiving of 2004:

On November 19, the coast guard intercepted a thirty-two-foot speedboat about nine nautical miles south of Big Pine Key. Aboard were thirty-eight Cuban migrants; two smugglers were arrested. On November 30, a coast guard airplane spotted a twenty-three-foot boat. It was intercepted near the Marquesas, and eight Cubans were found aboard; one smuggler was arrested. On December 5, a coast guard cutter located a twenty-seven-foot boat sixteen nautical miles from Santa Clara, Cuba. The vessel was found to contain twenty-five Cuban nationals. Two men were arrested.

The total in fewer than three weeks was seventy-four illegal migrants and five people arrested. While the financial gain isn’t in the same league as cocaine, the human smugglers are still making big money. To use the preceding example, if the seventy-four people being smuggled each paid $5,000, that’s a total sum of $370,000 for three trips between Cuba and the Florida Keys. Not bad money for less than one month’s work.

OPERATION HONEYMOONERS

Call him “Mr. Lucky.” Imagine being married seventeen times. In fact, Mr. Lucky had girls from several South American nations lined up to marry him, all so they could obtain a coveted green card from the U.S. government allowing the ladies to stay in the country permanently.

Mr. Lucky was part of a marriage fraud ring broken up by federal agents in 2005 following a two-year investigation. Thanks to a compliant employee at the Miami-Dade County Clerk’s Office and several thousand dollars from each “fiancée,” Mr. Lucky and others racked up roughly half a million dollars in profits. Thirty U.S. citizens were involved in 102 bogus marriages.

The easiest way for an alien to obtain a green card is marriage to a U.S. citizen. Immigration officials know that and regularly quiz the happy couple before bestowing their blessing (on the green card application). It’s a tough interview, designed to weed out the imposters.

However, Mr. Lucky’s gang knew that and took precautions. Elaborate weddings were videotaped, rice flying and glasses clinking. The ring (smuggling, not wedding) included notaries (who can perform marriages in Florida), brokers (to find just the right mate, nudge-nudge, wink-wink) and a very easygoing Miami-Dade County Clerk staffer who presided over the marriage license bureau (how convenient).

Vheadline.com, the Venezuelan electronic news service, reported ringleader Evelyn Ramos Cemprit worked with a paralegal—the marriage license bureaucrat—and thirty Americans willing to “get married.” People from Venezuela, Peru, Colombia, Israel and Germany were victimized, paying $5,000 for the opportunity. Authorities said they would not be prosecuted but would be deported.

The penalty for aliens is immediate deportation and inability to obtain a green card in the future. U.S. citizens face five years in jail for willfully sidestepping immigration law.

The St. Petersburg Times reported on October 2, 2005, that the investigation began when an Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent noted one woman had been married seven times in two years. Once underway the inquiry was dubbed Operation Honeymooners. In 2005, 252,193 people received a green card after marriage to a U.S. citizen.

CRUISING TO AMERICA

Until immigration controls were tightened in the aftermath of the Al-Qaeda attacks in New York and Washington, a novel form of alien smuggling was practiced aboard Florida’s ubiquitous cruise ships. It relied on what was called “en route processing.” Thousands upon thousands of illegal aliens enjoyed a pleasure cruise from the Bahamas to Florida and an unfettered entrance into the United States.

For a trip from Fort Lauderdale to the Bahamas and back, an Immigration and Naturalization service inspector boarded the ship in Florida and stayed in a free stateroom. Upon arrival in Nassau, the inspector was free to shop and tour the city. Once embarked back to Florida, the ship broadcasted an announcement on the public address system asking all non-U.S. citizens to appear at the inspector’s stateroom. The appearance was voluntary.

Once the ship returned to Fort Lauderdale, all the passengers disembarked without any further document checks. Thus any alien could board in Nassau, skip the voluntary document check en route and walk down the gangplank into the United States. The trick was getting aboard in Nassau.

Joel Brinkley reported in the New York Times on November 29, 1994, that the Immigration and Naturalization Service had no idea how many aliens entered the U.S. using the “en route processing” dodge. But an undercover study by the Border Patrol indicated thousands of people were smuggled into the country. Brinkley wrote:

The agency cannot say how widespread alien smuggling aboard the day-cruise ships really is or what nations most of the aliens come from. But a five-year undercover investigation by one of Mr. [Lloyd] Lofland’s Border Patrol agents found that day cruises had become a favorite way for criminal organizations to smuggle aliens and drugs into the United States. In fact, the investigation, Operation Seacruise, showed that foreign criminal gangs used the cruises to smuggle their soldiers into the United States, where they sold drugs, smuggled weapons, committed ‘homicides, assaults, drive by shootings, and other terror tactics,’ a Border Patrol report said.

The scam was virtually foolproof. A ringleader in the Bahamas would offer to smuggle aliens into Florida for $1,000 each (or more). The ringleader would then telephone his partner in Florida and give a head count. An equal number of smugglers in Florida would buy tickets (often as cheap as $100) and use a voter registration card as proof of citizenship to board the cruise ship. At the time, no identification was required to register to vote and obtain the card.

In the Bahamas, passengers would be issued a boarding card permitting reentry to the ship. The smuggling chief would collect the boarding cards from his fellows and go ashore. The remainder of the smugglers would stay aboard. The boarding cards would be handed to the waiting aliens.

As the legitimate tourists thronged back to the ship, the aliens would mingle and show their boarding cards at the gangplank. Once aboard, they could ignore the “en route processing” and disembark in the United States unmolested. As the smugglers grew more confident of the route, they often told aliens to take a kilo of cocaine with them. The scam seemed foolproof.

Brinkley wrote that when the Justice Department questioned the practice of “en route processing,” the Immigration and Naturalization Service defended it. “In a report issued last April [1994], the Justice Department Inspector General urged the immigration service to abandon en route inspections, calling them ‘improper and inefficient.’ The immigration service defended the practice, saying, ‘The risk of illegal aliens entering the U.S. using cruise ships is low due to the quality of cruise-line personnel, the general type of vacationing passengers who routinely travel on cruises and the low frequency of detected illegal aliens.’”

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, procedures were tightened up and now resemble the screenings routinely conducted at airports. The open door is now closed. But for decades, Florida’s cruise ports were the site of frequent and flagrant immigrant smuggling.

THE NEW SLAVERY

Florida is also in the thick of the new slavery: “human trafficking.” These three cases were reported by the Palm Beach Post staff on December 7, 2003, in a special report titled “Modern Day Slavery.” As revealed in this report, sometimes the trafficking concerns an individual slave:

Collier County sheriff’s deputies answered a domestic abuse call at the house of Guatemala native Jose Tecum in Immokalee one night in November 1999. They found Maria Choz, 20, consumed by tears. She said Tecum was keeping her as a slave. Choz and Tecum were from the same area in Guatemala. Tecum had tried to buy her from her poor family, Choz told police. He eventually raped her and threatened to kill her or her father if she didn’t come to Florida with him. Tecum made her live in the same house with his wife and children and forced her to have sex when his wife was not there. He found her work in the fields but took almost all the money she made. In 2000, Tecum was found guilty of involuntary servitude, kidnapping and smuggling and in 2001 was sentenced to nine years.

And sometimes the crime is more systematic. Again, the Palm Beach Post:

In November 1997, two 15-year-old Mexican girls escaped a trailer near West Palm Beach and told authorities a brutal tale. They said they had been smuggled into the United States by a Mexican family and promised work in the health care industry. Instead, they were forced to become prostitutes, working in a string of trailers around south and central Florida—several in Palm Beach County—that catered to migrant workers. They were warned that if they tried to escape, their family members in Mexico would be harmed. They were told they had to work off $2,000 or more in smuggling fees. They were paid only about $3 per sexual encounter, minus extra debts such as medical expenses. At least two dozen other women worked in the brothels with them—some as young as 14. Prosecutors later said the people-smuggling and prostitution racket was run by Rogerio Cadena, originally of Veracruz, Mexico, and about seven family members. Prosecutors accused the Cadena family and its employees of brutalizing women—beating them, forcing them to have abortions, locking a rebellious girl in a closet for 15 days. In January 1999, Rogerio Cadena pleaded guilty, was sentenced to 15 years and forced to pay $1 million to the federal government.

And sometimes there is no smuggling involved. The slaves are “recruited” locally. This story also is from the Palm Beach Post:

In April 1997, a team of St. Lucie County sheriff’s deputies, on duty near Fort Pierce, was approached by George Williams, who said he’d just escaped from a house where he had been held against his will and beaten by a labor contractor named Michael Allen Lee. Williams and other men had been recruited from homeless shelters in central and southern Florida and forced to work picking crops for Lee. Prosecutors later said Lee often paid his workers in alcohol and drugs, including crack cocaine. He charged up to $40 a gallon for cheap wine. He beat them if they tried to leave. Williams and nine others filed a civil suit against Lee and his business associates, which was settled in January 1999 for an undisclosed amount. In December 2000, a federal grand jury indicted Lee on the criminal charge of servitude. He pleaded guilty, and in 2001 he and another defendant were sentenced to four years in prison.

The enduring and pernicious nature of smuggling in Florida is demonstrated amply by its role in the centuries of slavery. Whenever slavery was illegal, smugglers supplied slaves. Their techniques foreshadow those used by untold generations of smugglers—the use of the sea as well as the role of Florida’s island neighbors.