WHAT ABOUT LIFE in the Party, how members live, who they are, how they earn their money, what they do with their time, and how they get their orders? The following are accounts of day-to-day activities of Party life.

Eleanor is washing the dishes. Her husband, Henry, has just gone to work. The two children are scurrying around the house, ready to leave for school.

Suddenly there is a knock on the door. It is Ruth, who lives across the street. Ruth is chairman of the East Side Communist Club. Her husband, Robert, is state secretary of the Communist Party and a full-time paid functionary.

“Starting the day out just right,” smiles Ruth. “The kitchen is all cleaned up. You can come and help us.”

Ruth outlines her plans. The state office needs some typing done this morning. Eleanor was a stenographer before she married and often helps on a part-time basis at headquarters. She is a trusted member. But that is not all. In the afternoon Eleanor is to make “some calls” that is, visit some comrades. She must pass out word that the next meeting of the county executive committee will be held on Friday evening. This message cannot be given over the telephone. Then tonight will be the regular meeting of the East Side Club. Eleanor probably won’t get home in time to fix supper. If she doesn’t, Henry and the kids can make some cold meat sandwiches. Besides, Henry is scheduled to meet with the state education secretary tonight and he won’t have time to eat supper anyway.

Life in the Party! For good members nothing is left for life outside the Party. The housewife is doing typing, running errands, Mimeographing, arranging meetings, collecting dues; her husband, even while working at the grocery store, in the shoe factory, or at the service station, is thinking of his Party assignment that night, distributing literature, soliciting money, serving as a courier. The Party is the most important force in their lives.

If anybody joins the Communist Party expecting to lead an easy life, perhaps read Marx and Engels, buy some literature, and not exert much effort, he is completely misguided. Party work is hard, tough work, and the Party is a ruthless taskmaster. The member is always on the run, doing this and doing that. He has no spare time, energy, or money for himself. His whole life becomes dominated. The Party is his school, source of friends, and recreation, his substitute for God. Communism wants the total man, hence it is totalitarian. That is part of its indoctrination policy: by concentrating everything on the Party, all other interests are squeezed out.

Day and night the Party structure is buzzing with action: fund drives, registration of members, collection of dues, sale of literature. Leaflets must be passed out on Olive Street, a picket line formed at city hall, a meeting attended. Workers, not playboys, are wanted; or as one Party spokesman expressed it, we must rid ourselves of the member who “makes noises like an eager beaver but accomplishes little.” A major characteristic of the Communist Party is perpetual motion.

The man who keeps this subversive beehive of activity going is the paid Party functionary. He is the key to the whole apparatus. Working on national, state, and local levels, he pumps in energy, gives orders, coaxes, cajoles, threatens, smiles, scowls, pleads, anything to keep the Party bustling.

Most communist functionaries are old-timers with ten, fifteen, or twenty years of service. Some have been trained abroad, possibly in the Lenin School in Moscow. They are transferred at frequent intervals, depending on the needs of the Party. One may serve as an organizer in California, as a section secretary in Rhode Island, or as a fund-raiser in Florida. Their full-time job is to advance the communist cause. The Party employs women functionaries, especially on the lower levels. During World War II, when many male comrades were drafted, a number of Party offices were run by women.

Salaries vary, depending on the size and location of assignment, but they average fifty to seventy dollars weekly. As a general rule, officials are paid by the local organization, although the national office, in case of a deficit, may step in with cash. Some functionaries operate on an expense account, especially if they travel.

The communist official will probably live in a modest neighborhood. His wife will patronize the corner grocery store, his children attend the local school. If a shoe store or a butcher shop is operated by a Party member, the official will probably get a discount on his purchases.

Most Party officials drive cars, usually older models. They are generally out late at night attending meetings. A car is essential for transportation and carrying literature. Except for special affairs, communist activity is slight early in the morning. The organizer, coming in around midnight or one o’clock, will sleep late. But that doesn’t mean all day. One Southern official was severely censured for sleeping too late; to solve the problem the Party bought him an electric alarm clock.

Functionaries eat away from home a great deal. They generally are well versed on “cozy” places where they can talk with a minimum of observation. Much Party business is conducted at luncheon appointments. Their wives are also engaged in Party work, and often both are away from home night after night. “Home,” to the communist organizer, is more a place to sleep than to enjoy restful relaxation.

If a Party convention is to be held, and many out-of-town delegates are coming in, the organizer may turn his apartment into a temporary hotel. He will pull out all the spare cots, beds, and blankets and “put up” a half-dozen visitors.

The paid official’s job is to keep the Party going, to see that everybody has something to do, that meetings are scheduled, that money is collected, that the Party’s program is carried out. He may start his day around ten-thirty or eleven o’clock with a “staff” conference at headquarters. There he will discuss the day’s agenda with other officials, give or receive orders, and get squared away for the day’s work.

The organizer must be a fairly intelligent man with an ability to get along with people. He is always asking for something: Can you deliver papers, how about attending this class, making a speech? He must know how to overcome fears, suspicions, and laziness, and encourage members to work. He may, for example, approach a member for a donation: “We need five hundred dollars. Sell your car and donate the money.” Communists come up with all kinds of schemes. The organizer must go out and “sell” the idea.

He also spends a great deal of time smoothing out personal problems. In one case a communist “love triangle” erupted. A young Party member, even though married, decided that she loved another member’s husband. The man’s wife, however, was determined to fight. The problem reached such bitterness that the trio’s Party work began to suffer. There was little hope of solving it by themselves. So the state chairman stepped in.

He talked to them personally. They poured out their inner feelings. The young woman and her “lover” requested Party approval for a divorce. A few days later the wife, with fire in her eyes, told the state chairman she wanted three months’ leave of absence from the Party to regain the love of her husband. A regular free-for-all was brewing. The Party, however, exerted pressure and the situation was settled. No divorce was approved. The organizer must be ready at any hour to settle everything, from a hair-pulling contest to the distribution of an estate.

For most members the Party is their whole life. If any problems arise, changing jobs, adopting a child, lawsuits, etc., they solve them with the Party’s advice. If a member has a case of ulcers, the organizer will recommend a “Party doctor”; if somebody is threatening suit, he will suggest a “Party lawyer”; if one has lost his job, he might know somebody in the Party, perhaps the owner of a store, a union-shop steward, or an industrial executive, who will help out.

The Party, in many respects, is a vast paternalistic system. Not that it is humanitarian, full of mercy, or interested in the members’ welfare. Nothing like that. The Party’s interests come first. If a member is sick, tied up with a lawsuit, or unemployed, his Party work will suffer. Each member should be in top working shape at all times. The Party functionary’s job is to seek out and solve these problems. He is an administrator, expediter, and nursemaid.

Also, any activity that might injure the Party must be pre-vented. The discipline of the Party, exercised through the functionary, extends to the most intimate details of personal life. Here are a few actual cases:

“A member in Ohio desired to adopt a child whose parents were members of the Catholic Church, and the member had taken steps to join the Church. The state chairman was furious and said no. Finally the member asserted his independence and left the Party.”

****

“Another member, in the Party’s eyes, manifested “bourgeois” tendencies. He spent too much time working on his house! He was removed from his Party position.”

****

“One member in the state of Washington went to Alaska, without permission, to secure a job. He was suspended on the ground that he would attract the FBI’s attention in Alaska.”

****

“A member in New York City, age thirty-five, was dropped from the rolls. Why? In the Party’s eyes he was too much dominated by his mother.”

Sometimes the functionary will order the member to take an affirmative step:

“A strawberry farmer was visited in Everett, Washington, by a Party fund-raiser who demanded one hundred dollars, which the farmer did not have. The farmer was ordered to mortgage his house. He refused and was expelled for failure to abide by Communist Party discipline.”

****

“In Philadelphia the district organizer called at the residence of a couple with a long record of devoted Party activity. The organizer announced that the wife was being dropped from the Party because she was anticommunist. When pressed for an explanation, the organizer stated he had concluded that the wife had written critical letters regarding the Party leaders, which she vigorously denied. The organizer then advanced a further reason. A news account had appeared in the papers recounting that her brother, an Air Force Reservist, had been killed in a plane crash and she had failed to advise the Party that he had been called to active duty. The wife then made the futile complaint that, since she was being dropped from the Party and not expelled, she had no way to appeal the decision or to defend herself. Then the organizer told the husband that he had to either leave his wife and children or be dropped from the Party. When he elected to remain with his wife, he was ousted from the Party, as was a former Party organizer who continued to associate with the wife.”

****

“A promising young communist was attending a Communist Party training school in New York. He was called out of class and advised that the Party had decided that he was to marry a young lady who had just arrived from Hungary on a student visa. The Party felt the girl was promising Party material. The communist went to City Hall accompanied by a fellow student, the bride-to-be, and her sister. The ceremony was performed, which enabled the girl to stay in the United States since she was now married to an American citizen. The marriage was in form only, and three years later the girl secured a divorce. In the meantime the young communist was sent to West Virginia as a functionary and started living with another girl. She also had a citizenship problem. This was met when the two were called to New York for a meeting. In passing through Elkton, Maryland, they secured a marriage license and returned after the New York meeting for the ceremony. The girl then went on to Chicago. When the communist finally met the lady of his choice, he went to a communist lawyer who arranged for an annulment of the second marriage on the ground that a prenuptial agreement to join the church had been violated.”

The Party functionary can order members to resign from one job and accept another, to move from one town to another, to stop seeing their families and friends, to lie, cheat, or steal.

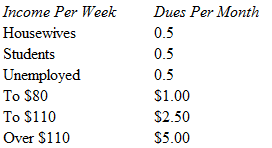

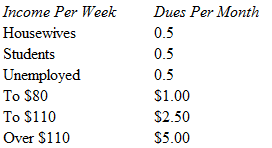

Then there is the problem of money. The functionary is always prodding. First, members must pay dues. They are collected monthly from each member and give the Party a substantial source of revenue. Payments of dues are based on regular schedules, depending on a member’s income. Here is a sample schedule:

Dues also serve another purpose: to control the member. The Party official can keep track of him, see if his interest is waning (if he doesn’t want to pay), and also, if possible, determine how much money he actually has (which the Party can later extract). If he falls behind in payments, the financial secretary will be right after him.

Another related obligation is to donate money (besides paying dues). Every member must pay, and pay until it hurts. The Party conducts an annual fund drive, involving the whole membership. Goals are set for clubs, sections, regions, and on a national basis. A big celebration, perhaps a dance or a dinner, marks the “kick-off,” and a definite conclusion date is established. During this period, say September 1 to October 15, a white heat of intensity is reached. The theme: “Money, money, money.” No member, regardless of excuse, is spared. If the amount isn’t reached, the campaign is extended.

How much should a member give? Usually a week’s wages is the accepted minimum. If a comrade has extra sources of income, the amount will be higher.

The Party raises money, lots of it. In one fund drive alone, for example, national headquarters announced a collection of over 165,000 dollars. And the campaign was still not complete. The nickels and dimes (although communists say they like “folding money” best) soon add up. With the effectiveness of a vacuum cleaner, the Party pulls money from everywhere.

Laggards, renegers, and backsliders are pushed hard. “That’s not enough. You’re a piker,” the Party organizer will scoff. Sections and clubs vie for “collection honors.” The first state or district to reach its quota is enthusiastically hailed.

But that is not the end of “donations.” Time after time there are assessments or special fund drives. They come like snow-flakes in a winter storm. Party leaders have been arrested, they need help! (Defense Fund). The Daily Worker needs money—urgently! (Press Fund). The Party must have 100,000 dollars in thirty days! (Emergency Fund). An “emergency” is always stalking the Communist Party. The best way to solve it is money. The only thing better is more money. The cost to members: at least a day’s pay for each special fund.

Fund drives do not exhaust the financial wizardry of the communists. Money is obtained in still other ways, such as Hallowe’en parties, dances, waffle parties, going-away affairs, testimonial dinners, anniversaries (such as of the October Revolution in Russia or the birthday of Lenin). In most instances tickets are sold and, in addition, a collection may be taken up. Everything you have belongs to the Party. That’s the philosophy.

One top leader explained how to obtain contributions. Visit the prospective victim. Take along an out-of-town comrade (he’s the high-pressure expert) and a local member. The latter should have plenty of money with him. The prospective victim might say, “Yes, I’d like to contribute, but I haven’t any money now”—the easy way out. If so, the local comrade would interrupt and say, “Fine, I’ll lend you the money. Would a hundred dollars be enough?” This squeeze always works, the leader said. Blank checks are also carried.

To show how far money-raising can go, one member dreamed up the idea that bodies of deceased comrades should be sold for medical experimentation. The Party would gain doubly: first it demanded the fee for the cadaver and then the money ordinarily spent for the burial. Another member suggested that gifts no longer be given at “stork” showers for expectant mothers. This money should be donated to the Party.

Then there are extra revenue sources. At the end of World War II, Party officials requested comrades returning from military service to donate part of their bonus money. In many instances they set the actual amount. If the member didn’t comply, he might be disciplined.

Estates are also juicy morsels. If members, or maybe sympathizers, have any extra money, the Party urges that wills be executed naming the Party or certain functionaries as beneficiaries. Large sums are thus often gained.

Some years ago a former Episcopal bishop died in Ohio. Years before, during an illness, he had started reading Marx and other communist books. Then he turned author and wrote a book entitled Communism and Christianism, wherein he expressed doubt that Christ had ever lived, and asserted that he had “found Christ via Karl Marx.” The bishop was given a trial by his church and deposed. Following his death, his will provided that the residue of his estate, valued at between 300,000 and 400,000 dollars, was to go to a corporation whose trustees were to devote all or any part of it to the cause of communism as “propagated by Karl Marx.”

Another communist sympathizer in Oregon a few years ago received more than 100,000 dollars upon the death of a son. A communist friend persuaded the sympathizer to bequeath a part of his estate to two West Coast communists.

A Party member died in Massachusetts in 1953, leaving a 14,000-dollar bank account and real estate to the Party, naming three Party officials as executors of his will.

Over the years the Party has been blessed by angels and foundations whose money was made through the American free enterprise system and is then used in an attempt to destroy the system that made wealth and affluence possible.

In years past, each member was given a membership card or book (which was numbered) on which he could paste his “dues stamps,” showing that he was current on this obligation. But today, for security reasons, this practice is no longer followed. Membership records, if kept, are carefully concealed, and only a trusted few know their whereabouts. Sometimes elaborate code, color, and tab combinations are used on such records to indicate the name, occupation, sex, length of Party service, etc., of the members.

To join the Communist Party does not automatically mean life tenure. Memberships must be renewed every year or, in communist language, members are “reregistered.” This represents another means of control. If a member is delinquent in dues or donations, he’ll have to pay a penalty, perhaps contribute ten dollars, or be disciplined. These annual registration drives are important events in Party life. Each member is personally contacted. Clubs and sections compete for speed and percentage of successful registration. The drives usually start in October and often extend well past the December 31 deadline.

A member moves. His district organization will send details concerning him to his new area: name, Party history, whether dues are paid, along with any other remarks. A member may be given half of a dollar bill and the other half forwarded to the new district. When the member arrives, the halves are matched. Identity is thus established.

So it goes, a constant round of rushing, driving, pushing, paying, never time to stop. The member is regimented from life to death. His chief obligation: to follow instructions eagerly, energetically, obediently. He is a mere wisp of living matter, born, as a Daily Worker birth announcement proclaimed, “for swelling our ranks.”

This complete absorption in the Party creates an exhilaration that warps judgment. One comrade became so wrought up over the supposed superiority of communist culture that he cited statistics that the Soviet soldier in World War II was an inch taller and had a chest one and a half inches larger than his Czarist counterpart!

Such fervor sounds laughable, but it is symptomatic of paranoiac behavior. To an individual like this, any communist achievement surpasses anything American. This bigoted communist fanaticism drives members to mortgage their homes, spend years in underground shelters, and betray their native land.

Even in death a member may become a pawn to enhance the Party. The passing of a prominent comrade invariably is the occasion for a “state funeral.” The departed member is now a valuable showpiece and his passing is exploited to the fullest extent. On such occasions the deceased lies in state on the day of the funeral, with “mourners” passing the bier. A large, blown-up photograph of the deceased, draped in black, hangs at the rear of the stage. An honor guard of from two to four comrades stands at attention wearing red armbands.

There is seldom a religious quality to the music, eulogies, or the “mourners’ conduct. At the “state funeral” of Mother Ella Reeve Bloor in 1951 the “mourners” talked, laughed, and smoked.

The eulogies are numerous and recount the contributions made by the deceased to the Communist Party, to the advancement of socialism, and state how the Party can learn from the life of the departed. At Mother Bloor’s funeral in New York City, for example, Pettis Perry, a member of the National Committee, said:

“This is not farewell to you, Mother Bloor. We pledge to follow in your footsteps . . . We will build your Party and our Party and some day we will have a nation and a society built on the brotherhood of man . . .”

At the funeral of Peter V. Cacchione, an elected member of the New York City Council, nineteen speakers delivered eulogies. Gilbert Green, then chairman of the Party in Illinois, speaking for the National Committee, observed that the deceased fell in the struggle as “a soldier in the cause of human freedom,” and vowed that the remaining comrades would take “the banner from his hands.”

After such services a cortege of automobiles laden with mourners journeys from the funeral hall to the cemetery. As Mother Bloor was lowered into her grave at Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, New Jersey, Walter Lowenfels, then the Philadelphia correspondent of the Daily Worker, read Walt Whitman’s poem, “The Mystic Trumpeter.”

At the Cacchione interment Henry Winston, a member of the National Committee, delivered these parting words, “We are confident, as you were, dear Pete, in ultimate victory . . . We will carry out your heritage.”

Through it all runs the hope, not of life everlasting, but of communism everlasting—if the members can be stirred up to work harder.