If the main concern of the first settlers was the creation of an orderly, secure society, where they could gain access to land, and the finance and infrastructure to service it, the goals of the first wave of politicians who met in Auckland in May 1856 centred on the creation of prosperity and a more widely based economy. This required a steady flow of immigrants and a faster rate of land settlement. Inevitably this led to confrontation with Maori. The New Zealand Wars of the 1860s produced a decade of insecurity as settlers and Maori fought over whose authority was to be paramount. Maori eventually lost this struggle because rapidly increasing settler numbers tipped the balance of power against them.

Provincial governments wielded local power and built roads and bridges. They also contributed in varying degrees to educational and health needs. But the over-arching importance of central government grew at the expense of provincialism, largely as a result of the war. The financial basis of the provinces, which had never been strong, declined further once central government took decisive steps to expand the economy as well as its infrastructure in the 1860s and 1870s. The abolition of the provinces in 1876 led on to further extensions of central authority. This meant that local government in post-provincial New Zealand never became more than a junior partner. The paternalistic power of central government was the dominant feature of New Zealand life by 1890.

In the seven years between the censuses of December 1851 and December 1858 the European population in New Zealand more than doubled, reaching almost 60,000. Settlers now equalled the total number of Maori, whose ranks had been thinned by war and disease.1 Considerably more than half the settlers were young men; in 1851 there was only one person in Auckland over the age of 60.2 While all the settlements grew, the easier terrain and smaller numbers of Maori in the South Island meant that the new districts of Canterbury and Otago expanded quickly. Altogether 15,612 Wakefield settlers had been brought to New Zealand by 1854.3 Auckland was the largest of the unplanned settlements. According to Russell Stone there were about 10,000 people living on the Auckland isthmus by 1856.4

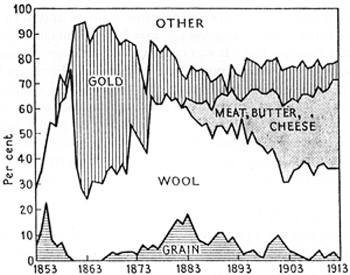

As settlers poured into New Zealand they pressured the Crown to speed the rate of land purchase from Maori. Those who had already acquired land were engaged almost entirely in agricultural production for local and Australian consumption. New Zealand’s overseas earnings derived from official salaries paid by the British Government, from the export of foodstuffs to the Australian goldfields,5 especially during the years 1851-55, and from wool, kauri gum and flax. Together this income funded the imports necessary for New Zealand’s expanding population. Milling timber, fencing land, cultivating grain crops, planting grass, cutting flax, husbanding sheep and building houses were the occupations of settlers in all provinces, while those in the north also gathered kauri gum. The nearest thing to a staple money-earning export was wool. By 1861 there were approximately 2 million sheep in the country, a figure that grew to 10 million a decade later.6

The first wave of politicians that gathered in Auckland in 1856 was a varied group. They shared youth, some claims to be educated and a fair propensity for vituperation. When they arrived the capital was in recession. This was due largely to a fall-off in Australian demand as the steam went out of the Victorian gold rushes after 1855. Auckland’s commercial leaders who dominated provincial politics tried to break out of stagnation by encouraging rapid immigration to their province. New settlers were offered 40-acre farms.7 Further south, several of Taranaki’s early politicians prospered from providing services to troops stationed in the area. They championed faster land purchasing, immigration and public works.8 Edward Stafford was Nelson’s leading politician and became New Zealand’s longest-serving nineteenth-century premier. He came from an area where, to quote Jim McAloon, ‘if the settlers were aware of the [Government’s] budgetary problems they gave no sign of it’. Stafford was a devout advocate of roads and bridges as well as an active immigration policy. These he saw as vital to small farmer prosperity.9 In Scottish Dunedin where the small settlement of 600 people had as recently as 1852 gone eight months without news of its nearest neighbour Canterbury, a desire for more immigrants, better shipping connections with other settlements, public works and railway construction enlivened public debate for the rest of the decade.10 Development was on everyone’s lips.

In spite of sections 18 and 19 of the 1852 Constitution specifying the functions reserved to central government, there was always confusion over which jurisdiction was responsible for providing some services.11 In return for a portion of the customs dues and the revenue from the disposal of lands that had been bought by the Crown, the provincial governments were expected to deal with local matters, especially those affecting the general health, education and welfare of their people. Central government, on the other hand, had responsibility for the courts. It administered the criminal law, ran the Post Office, maintained coinage and currency and, under the Treaty, was expected to guarantee the ownership of land to which Maori had not yet surrendered title. The General Assembly was made up, for the most part, of provincial leaders who regarded themselves as delegates from their provinces. Most sang variations on a common tune: they lacked the finance to provide adequate services and expected central government to assist. Virtually all their complaints can be traced back to money.

Edward Stafford, the longest-serving nineteenth-century premier, struggled to expand New Zealand’s economic base. ATL F-12439-1/2

Stafford’s Ministry held office from June 1856 till July 1861 and again in 1865 till 1869. The secret to his longevity in an era marked by fierce debate and ever-changing political coalitions was his optimism about the future of New Zealand, a commonsense approach to government, and his willingness to use central government pragmatically. Henry Sewell’s Ministry lasted only one month in 1856 but he served as Colonial Treasurer in Stafford’s Government before going to Australia and then London later that year. While still a Member of the Executive Council he acted in Britain as ‘a sort of proto high commissioner’.12 Stafford wrote to Sewell at length, outlining various proposals to strengthen the colony’s economic base, and asking for his assistance, particularly in securing British Treasury backing for a half-million pound loan. If Sewell could secure Treasury support it would mean a lower interest rate from London financiers. Stafford sought to restructure the Government’s existing debts and to purchase more land from Maori. He also wanted to establish efficient shipping links both within New Zealand and abroad. Chambers of Commerce, which were developing in the main centres, and several MHRs expressed their ‘utmost’ support for any moves by Government to contribute towards the cost of shipping services. Sewell enjoyed some success; by October 1857 a general restructuring of New Zealand’s debt was under way. The development of a reliable shipping link to London, however, took another 30 years, despite the Government’s offer of generous subsidies.13

Stafford also sought to widen the country’s economic base by fostering industries deemed to have economic possibilities. The potential of flax had been discussed for a decade. On 20 December 1856 Stafford’s Government gazetted an offer of a reward of £4,000 for the ‘discovery of efficient means for rendering the flax and other fibrous plants of New Zealand, available as articles of export’.14 Government thinking had been amplified a few weeks earlier by the Colonial Secretary’s chief officer. William Gisborne wrote to Baron de Thierry: ‘The Government are aware of the difficulties which attend the establishment of a new branch of trade…. These difficulties it will be their anxious desire to remove as far as possible…. The House of Representatives … are now considering the question of offering to assist by a limited advance of capital a company or companies, should such be found to consist of responsible mercantile men of established character on terms which may secure the Government from loss. If mercantile men of this class cannot with such offer of assistance be found to embark in this undertaking, that will be evidence that as yet the matter is not ripe for serious consideration by Government.’ In effect, if such endeavour was successful, then at that point the reward would be paid out. When de Thierry sought the reward up front to enable him to expand his flax works, Gisborne informed him: ‘it is not thought advisable to appropriate public money to the prosecution of a private undertaking’.15 Clearly there were limits to the Government’s interventionist inclinations.

An industry employing mostly Maori in its early days, flax became the subject of much government attention as inventors constantly sought to uplift the reward by claiming to have invented machinery that would scrape from the leaf its glutinous substance and then wash it.16 But the Government’s ‘mercantile men of established character’ were slow to materialise. The reward lapsed. Flax exports were averaging only £56,000 pa by the end of the 1860s. A desire to stimulate the flax industry took on renewed urgency when the economy turned down in the late 1860s. In a lengthy debate in August 1869 parliamentarians from all parts of the country lent their support. John Hall from Canterbury, who later became a rather crusty, conservative premier, urged the establishment of a Flax Commission to collate information. In his opinion it was ‘imperative’ that Government ‘do its best to foster any native industry which would help to relieve the Colony from its present depression, by furnishing a valuable article of export, and thus affording employment to a considerable number of persons’. The newly appointed Colonial Treasurer, Julius Vogel, endorsed these sentiments. Other MHRs saw the role of government to be one of stimulating, rather than usurping market development of the industry. However, the then Premier, William Fox, had doubts about government stimulation of trade, arguing that if an industry was viable, the marketplace would soon make that fact clear. It was left to the recently defeated Stafford to explain the majority sentiment in favour of a commission; in the process he tried to define a boundary line to public assistance: ‘Where any particular manufacture had been long established, Government interference would be pernicious; but where it was sought to create a new article of commerce, and make known in what way it could best be brought to market, the isolated knowledge of a few individuals might with advantage be collated….’17

Baling flax fibre in Northland about the turn of the century. ATL G-10555-1/1

The Flax Commission was gazetted on 15 September 1869. Gisborne told the newly appointed commissioners: ‘The Government anticipate that the result of the labours of the Commissioners, whose knowledge of, and interest in the subject... are well known, will be productive of important benefit to the industry and commerce of New Zealand’.18 Hearings were held, but the Commission never produced a booming industry. Years later in 1893 the House of Representatives established a select committee to investigate the potential of the flax industry. It strongly urged Seddon’s Government to ‘encourage’ the industry with an offer of further bonuses. These were made available once more, but proved hard to uplift. Few men of substance were prepared to risk much capital. At its peak around 1906 there were 240 small mills in operation, employing approximately 4000 people. They were to be found mostly in Northland, Manawatu, Canterbury and Otago and produced flax worth £557,000. The industry then declined even though the Government was now paying bonuses on processing machines. A yellow leaf disease hit crops. During World War I overseas demand surged briefly, and 32,000 tons were exported in 1916. Prices subsided after the war, but politicians nursed hopes that government subsidies would revive the industry during the Great Depression. Assistance for the production of linen flax was forthcoming after 1935, and an industry was producing linen flax on a commercial basis by 1940. More than 20,000 acres of flax was being cultivated for processing and export by 1942. Demand fell off after World War II. Only two factories, one at Geraldine, the other at Fairlie, remained in operation by 1957. They were under the jurisdiction of the publicly owned Linen Flax Corporation.19 This early government experiment in picking an export winner clearly failed, although in the interim many people had been employed in a subsidised industry.

Stafford’s hope for a timber industry had better long-term prospects, although there was to be little progress in his lifetime. In the middle of the 1850s some concern was expressed at the speed with which New Zealand’s native forests were being milled or burned. In 1856 Stafford’s Government despatched samples of many kinds of native timber to Sydney for analysis of their properties and relative strengths.20 The premier hoped for wider usage of native timbers, and better management as well as replanting of popular species. These goals gained some currency after the visit of the Austrian geologist, Ferdinand von Hochstetter in 1858. A few years later the House paid for a translation of his book, which criticised forest management in New Zealand. By the end of the 1860s parliamentarians were convinced that better use should be made of New Zealand’s forests, many of which were being wasted in the rush to produce pasture. Central government began subsidising replanting in the provinces of Canterbury and Otago in 1871. A study by Dr James Hector of the Colonial Museum in 1873 argued, however, that milling of timber was best left to private enterprise.

Central government continued to take the lead in urging better forest management techniques. The first Forests Bill was introduced in 1874. However, after complaints from provincial councils about the setting aside of forest land as security for railway loans, the Bill was amended before passage. The truncated Act provided for an annual sum of £10,000 for 30 years to be paid out of the Consolidated Fund for state employees to manage and develop forests. By 1906 this had risen to £20,188 pa.

The first Conservator of Forests, Captain J. Campbell Walker, was appointed in 1876. His job was to collect information on New Zealand’s forests, and to make submissions about the creation of a State Forests Department. Over the next decade it was established within the Lands and Survey Department. Counties, especially in the South Island, were granted parcels of Crown land for afforestation purposes. Research was undertaken that involved plantings of indigenous and exotic trees at Whangarei and Te Kauwhata. Under the State Forest Act 1885 authority was given for reserving state forests, establishing a school of forestry and the hiring of more state employees. The depression of the 1880s limited government endeavours and some workers were laid off. However, forest activity revived in the 1890s under the Liberal Ministry. State nurseries sprang up in Whangarei, Rotorua, Seddon, Hanmer, Ranfurly and Tapanui. Between 1896 and 1912 a total of £96,593 was spent on nurturing 44 million young trees and planting them on nearly 19,000 acres. Government efforts rather than private vision drove early forestry policy. Private enterprise confined its efforts to milling and marketing. These were areas where the Government was soon showing an interest as well.21

In July 1896 a conference of timber merchants met in Wellington. The Premier, Richard John Seddon, addressed them. He invited suggestions about how the Government could further assist the industry. In a rambling speech that was a mixture of tub-thump and homespun theory, Seddon declared: ‘It has often been said in the past that governments should not interfere in matters that should be dealt with by commercial men…. We have been told time after time [that the timber industry] is not a matter for Government concern, but that those engaged in commerce and industries will settle it for themselves. Well, my experience through life has been this: that what is everybody’s concern is no one’s concern, and if you trust to everybody, you will find … that no one is doing anything….’ He cited various actions that his Government had taken such as sending a trial shipment of timber to London to test the market. After admitting that this experiment had been a costly failure due to an accident with leaking tallow en route, Seddon concluded with the words: ‘If the Government and all engaged cooperate together, and work together, then all will have a corresponding advantage’.22 This was a philosophy much repeated in later years as New Zealand developed what came to be called a ‘mixed economy’.

As a result of the conference a Timber Industry Board was established. The board urged the Government to undertake further trial shipments to London, which it did. None produced a profit. However, milling from Crown land and state forests produced a small but steady revenue for the Government. It totalled £146,000 for the decade 1894–1904.23 By 1907 the Government owned and operated a small mill at Kakahi in the King Country, the acquisition of which went beyond Hector’s advice of 1873. The mill made a good profit from its small operation. A Royal Commission made up mostly of parliamentarians examined the timber industry in 1909. It advocated afforestation programmes on Crown land deemed unfit for pasture. The report suggested that the State’s nurseries should provide all settlers with tree plants at a small charge.24 During World War I the powers of the Commissioner of State Forests were extended to enable a wider range of activities. Eventually a forestry branch was separated off from Lands and Survey in 1919. In the Forests Act 1921-22, the State Forest Service had its functions more clearly defined. By this time the area of state forests and provisionally designated land under SFS control amounted to 5 million acres, of which approximately 37,000 acres had been planted, some of it in exotic trees. A major expansion of the State’s interest in forestry was still to come.

The State’s early interest in stimulating industry was not confined to flax and timber. In July 1870 a parliamentary committee considered what steps were necessary to develop manufacturing industries. Over the next few years it concluded that simply encouraging immigration and building better communications were not sufficient to stimulate prosperity; parliamentarians ‘should do all in our power to promote the development of those industries which can be worked to the greatest advantage to the labouring classes, and thereby promote a constant flow of immigration’.25 The committee believed that the Government should accept responsibility for ensuring an adequate flow of water to potential goldfields so as to assist with sluicing, and should take over from provincial governments all regulations relating to the discovery and working of minerals. MHRs argued that a ‘suitable reward’ should be provided for discovery of tin that could be mined profitably, and that central government should lend for the construction of tramways or railroads to ‘any responsible company’ prepared to work New Zealand’s coal mines. The boundaries of state investment were being steadily expanded.

Import substitution industries with the potential to save overseas exchange and employ settlers were also promised assistance by provincial and central governments. In 1865 the Otago Provincial Council resolved to pay a ‘bonus’ to encourage paper-making in the province. The sums promised grew more enticing over the next decade and were payable on the erection of buildings and the installation of machinery. As John Angus shows, the Mataura Paper Mill Company received its initial stimulus from these subsidies.26 Central politicians, meantime, wanted the Government to pay £50 per acre for the first five acres of mulberry trees planted and cultivated for a minimum of two years, believing there might be a rosy future for a silk industry in New Zealand. If a mulberry grower could get a minimum of one hundredweight of silk cocoons with a market value of £50, then he should be paid a premium for this production not exceeding £500 per annum. The Colonial Industries Committee observed: ‘Where private assistance is afforded by the State in the manner now proposed, it is of the utmost importance to confine it to those who have taken up a subject enthusiastically, and made it, as it were, their specialty’.27

There is no evidence of strong opposition to the development of an activist State. The caution shown by Stafford’s Government in the 1850s had been thrown to the winds by the 1870s. Economic adversity led politicians to contemplate monetary assistance to many private enterprises. On 19 February 1874 the Government introduced a bonus of sixpence per gallon for the local production of kerosene. It had to be marketed ‘at a fair price, the quality being approved by the Government’. Any bonus claims had to be filed with the Colonial Secretary by the end of the year.28 The Colonial Industries Committee also recommended that any glass industry willing to produce bottles should also be paid one shilling per dozen bottles up to the first 10,000 dozen produced locally.

The prospect that the country’s west coast iron ore deposits could be used for manufacturing had occurred to several entrepreneurs as early as 1858. Inquiries were made to the Colonial Secretary about renting parts of beaches around New Plymouth. In the early 1860s authority to remove sand for experimentation was given.29 The Colonial Industries Committee after 1870 went further, arguing that development of the country’s iron ore deposits was worthy of a bonus of up to 25 per cent of the cost of any plant, and 25 per cent towards machinery. The Government remained cautious. When there were renewed calls in 1887 for steel subsidies for a private Taranaki company, the deepening depression caused ministers to decline the request ‘at present’.30

Not all recommendations from the Colonial Industries Committee were accepted by ministers. However, while he was in the United States in 1871, Julius Vogel, the Colonial Treasurer, gave instructions for the purchase of 4000 young mulberry trees. Limited funds were made available to assist experimental plantings. Yet, after more than a decade of effort, no substantial silk industry had developed, although some optimists still nurtured hopes for it in the late 1880s. The Auckland Evening Bell believed that silk, more than other industries, could perform a useful social and moral purpose because it could be worked on in people’s homes. The silk industry ‘leads people away from the crowded haunts of men and brings them face to face with nature, with all her healthful, moral and physical influences’.31 Throughout New Zealand history a wider moral purpose has often been ascribed to government intervention in the economy.

Provincial governments played their part in the economy. Several experimented with afforestation; both Canterbury and Otago imported a variety of seeds from California in 1871.32 Rewards were offered for the discovery of gold, and Southland set up a coach service to access the goldfields in the 1860s. However, assistance to industry was not seen by early politicians as aid-in-perpetuity. Many bonuses and other support mechanisms had time limits. The Colonial Industries Committee noted approvingly in 1870 that earlier tariff protection given to the domestic brewing industry could soon be dispensed with because local brewing and malting ‘has become so efficient’. MHRs did not favour ‘an indiscriminate system of protective duties’.33 In those days government assistance was of the ‘kick start’ variety; it was not to keep the engine running.

While governments sought to widen New Zealand’s economic base they realised that the pastoral industry was likely to remain the principal revenue earner in the foreseeable future. Assistance to agriculture dates from earliest times. Government agencies involved themselves in expanding the area of land under cultivation. The Crown purchased land from Maori but during the provincial period the provinces received the revenue from its sale to settlers. After 1876 the General Crown Lands Office with its eleven branches spread across the colony took over sales. They were made through Land Boards, although at first the rules varied within the former provincial districts. A Crown Lands Guide was made available to prospective settlers; it listed the quantity and quality of land available for sale or leasing. Revenue from sales went to central government’s Consolidated Fund.

Ministers encouraged clearing, felling and planting and regulated where necessary to safeguard the expanding pastoral industry. By 1882 more than 5.1 million acres of land was in production and had been broken up into 17,732 freehold holdings.34 In the 1860s and 1870s regulations were issued to protect New Zealand livestock from any imports of diseased cattle and sheep. In December 1877 in response to the plague of rabbits developing in the South Island the Government announced bonus payments for the export of rabbit skins under the Rabbit Nuisance Act 1876. Customs officers were required to verify the passage of the skins across the waterfront before money was paid out.

Two events during Stafford’s first premiership had a huge impact on the country’s economy. The first was the war in Taranaki that began in March 1860. Both the lead-up to it, and the war itself, became a bonding exercise between settlers and what they now regarded as exclusively their Government. The second was Gabriel Read’s fortuitous discovery of gold at Tuapeka on 25 May 1861, six weeks before the fall of Stafford’s first ministry.

The rapidly deteriorating position in Taranaki in early 1860 stemmed from the pressure which settlers placed on the Government to acquire more land, and the increasing reluctance of Maori to part with it. When war broke out the Governor and settlers called it ‘native rebellion’. Over the next five years fighting raged, simmered then ignited once more. After 1865 smouldering discontent erupted occasionally and continued to do so for the better part of the next two decades. By this time the rift between Pakeha and a majority of Maori ran deep. Maori faith in the protection afforded them by the Treaty of Waitangi had largely evaporated. Central government seemed to have given up on power sharing or any solicitude for Maori interests; for Maori, resort to arms seemed to be their only option.

When war broke out settlers rallied round their government. Messages of encouragement were sent to Stafford’s ministers from Wanganui, Wellington, the Hutt Valley and Hawkes Bay. Residents of New Plymouth wanted ‘prosecution of the present war until a permanent and honourable peace has been ensured’. Far removed from the hot spot, Charles Bowen of Canterbury declared that local people ‘feel their provincial prosperity depends in a great measure upon the maintenance of good order in the Colony at large’.35

The Government borrowed and spent, and the 20,000 British troops who served in New Zealand during the decade stimulated demand.36 The public service grew rapidly and gave New Zealanders an early taste of emergency government. There were four ministries between July 1861 and October 1865 before Stafford returned to office. Each rose and fell over its conduct of the war. Each sought to wrap its fortunes around settler security, welfare for soldiers or their widows, post-war prospects for those who had served, and the well-being of refugees from the front. War, as it has been in so many countries, became the engine of state intervention. Pensions to widows, medical care for those involved in the fighting, settlement schemes for ex-soldiers in the Waikato, and compensation to farmers, especially those in Taranaki whose land or possessions had been damaged as a result of the fighting, preoccupied the ballooning public service.37 By the time the fighting died down, most North Island settlements, and even Nelson, where many Taranaki women and children had taken refuge during the emergency, felt their lives to have been directly touched by the war, and by the Government’s attitude towards their welfare.

During the early years of responsible government MHRs surrendered considerable powers to the Cabinet. Files of the New Zealand Gazette show that ministries had gained powers to issue regulations on a wide variety of subjects. In the lead-up to the outbreak of hostilities with Maori in March 1860 the Government regulated the importation or sale of arms, gunpowder or ‘other warlike stores’.38 Orders in Council proliferated. Customs and quarantine regulations, new rules governing naturalisation, and alterations to land registry procedures were all spelled out in Gazette notices rather than in statutes. Businessmen soon found it prudent to consult the Gazette. Chambers of commerce sought and gained a place on central government’s ‘free list’ of recipients of the journal.39 Instruments allowing executive government to rule during a war are seldom surrendered in their entirety when peace returns. In this instance the lingering unease after fighting died down and the demands of the Government’s bold expansionary programme in the early 1870s required their retention. Parliamentarians occasionally complained about too much power being vested in the Governor-in-Council.40 However, like their constituents, most liked strong, authoritative government so long as it produced results.

By the later stages of the war, the Government was determined to increase immigration, principally to strengthen settler numbers against Maori. Ministers accepted the advice of the Lyttelton Times, which argued in April 1861 that it was the Government’s duty to ensure that employment existed before people were induced to immigrate.41 In April 1864 Gisborne set out in detail the rules that should govern the promises given to would-be immigrants from Great Britain. In cases of ‘actual necessity’, agents were to be instructed that ‘assistance’ could be given to emigrants before their departure. Intending settlers should be told that allotments of land would be ready for them on arrival, and that they would receive accommodation for up to two months after disembarkation. The Government would fund employment for at least six months after they arrived in New Zealand.42

Varying assurances were given to migrants over the next fifteen years. The promise of employment which was specifically set out in 1864, but implied more vaguely in later years, meant that encouraging industries with the potential to provide jobs became equally important. The need to bolster settlers’ sense of security was seen as necessitating some government involvement in the marketplace. The difficulty which ministers encountered was that most people who were ambitious to prosper had little capital. Governments were obliged to stimulate in the hope of providing a thriving economy and employment. For the overwhelming majority of settlers and their political representatives, questions of ideology seem never to have arisen. Pragmatism ruled.

Read’s modest gold discovery in Otago in 1861 provided an upturn in the economy during the war. The immediate effect was that 2000 prospectors per week, mainly from Victoria, poured into Otago. They doubled the population of Dunedin within six months. This rush continued until the winter of 1862 by which time the population of the whole Otago province topped 60,000. It dropped only slightly when some prospectors made their way across the Southern Alps to Hokitika’s brief rush.43 The fillip to Dunedin in particular meant that its urban population became the biggest of the four main cities.44 By August 1867 numbers at Thames in the North Island were on the increase and for the next three years there was a modest gold rush on the Coromandel peninsula. After 1873 the number of active miners in New Zealand fell away. Only in the late 1880s, with the aid of British capital, did gold exports rise again, this time much of it coming from the Waihi mine where the cyanide process of extraction was used. Overall the gold rushes in New Zealand were a pale shadow of those in Australia. New Zealand’s £46 million worth of gold produced constituted about 13.5 per cent of the Australasian total in the years 1851-90. 45

Nevertheless, the sudden net gain of 46,000 people between 1861 and 1865, with another 20,000 arriving over the next four years,46 answered many prayers. There was a brief air of recklessness. In Auckland alone, imported goods quadrupled between 1860 and 1864.47 Predominantly younger men, more Irish and Catholic than the earlier settlers, and none with much capital when stepping ashore, augmented the earlier settlers in such numbers that they finished off Wakefield’s earlier fond hopes of carefully controlled settlement.48 However, people alone did not spell riches. After 1864, with the war spluttering out in the north, and receipts from gold declining, the provincial economies subsided once more, causing central government to adopt a more cautious demeanour. Only Auckland retained a precarious prosperity into the next decade, buoyed for a time by proceeds from the Thames rush. When Stafford returned to office in 1865 he was staring at a deficit of £136,500. He had little option but to retrench.49

Dunedin’s High Street, 1862. ATL G-17877-1/1

Stafford and his principal adviser, William Gisborne, turned their attention to the country’s bloated bureaucracy. During the war central government’s employees had blown out to 1602, with many hundreds more working for the provincial governments. The colony’s total population stood at 202,000 at the time when the capital shifted to Wellington, holding its first meeting there on 26 July 1865. The shift provided the opportunity to prune central government’s payroll. A Royal Commission in 1866 examined all departments of State. New office management techniques were introduced, as well as a more orderly system for recruitment, promotion and dismissal. However, it proved hard to reverse the momentum of the last few years; staff lay-offs were few; central government’s employees still numbered 1476 in July 1869.50 By this time economic conditions had worsened. When wool prices dropped in 1867 several provincial governments had difficulty repaying their loans. Central government was in no position to assist. It faced the prospect of the British withdrawing their troops which would inevitably mean more spending from local coffers on domestic security. Central government put a stop to provincial borrowing. Public activity at the local level wound down, and provincial governments never revived.

In a burst of recession-inspired activity, central government now attempted to stimulate local investment. Stafford’s Government legislated to enable a public savings bank to be opened at every post office in 1867. Two years later, on Vogel’s initiative, a State Life Insurance Office was established. In 1873 a Public Trust Office opened its doors, its principal novelty being the creation of a Public Trustee to administer estates, particularly those of people who died intestate. There was a common thread to each of these moves. A government guarantee was extended to funds invested in each. In an era of some spectacular bank and insurance company collapses abroad, this reassured domestic investors. Moreover, the returns on life insurance and trust monies invested in New Zealand were potentially higher because the local rate of interest hovered round 5 per cent instead of 3 per cent paid by London-based institutions. While there were advantages for local investors, the Government also stood to gain. Money invested in New Zealand by settlers could be tapped by the State for its purposes. By the end of the 1870s, the Post Office Savings Bank, the State Life Insurance Office and the Public Trust Office had many of their assets tied up in government securities.51 The notion that New Zealand’s capital should be used for the advantage of New Zealanders was catching on, thus helping to edge forward the growth of a separate, independent colonial economy.

At first the concept of a Public Trust Office was controversial. A Public Trustee Bill was introduced in 1870. It passed the House of Representatives but was defeated in the Legislative Council. Throughout debates politicians grappled with the appropriate boundaries between public and private enterprise. Ministers stressed that there would be no compulsion to lodge private trust properties with the Public Trust Office. Critics argued that the State had no role at all in the investment of private funds. One parliamentarian declared that he was opposed to bills which ‘would have the effect of placing the private business of the country … in the hands of the Government’; another declared that ‘self-reliance was a habit that they ought to cherish in their fellow countrymen’.52 In 1873 a majority endorsed a modified Bill. Once more they were happy to use the powers of the State for wider purposes. The Public Trust Office became a respected, if small agency of State. A century after its introduction it administered more than 20,000 estates and funds with a value of nearly $220 million. By this time the Public Trust Office was investing only 20 per cent of its funds in government or local body stock.53

The defeat of Stafford’s Government on 24 June 1869 opened the way for a new burst of state activity. William Fox became Premier four days later with Julius Vogel as his Colonial Treasurer. A mercurial London Jew, who had made and lost money on the goldfields of Australia before becoming editor of the Otago Daily Times, Vogel was the most influential political figure in New Zealand for the next decade. In his view economic stagnation called for innovation. He produced it in his budget on 28 June 1870. It was a bold expansionary document based on the faster purchase of Maori land, assisted immigration, and active railways and public works programmes that would open up the land, thereby increasing production. The new policy, like the later ‘Think Big’ strategy of the 1980s, was to be financed by borrowed money.

The debate on the Immigration and Public Works Bill 1870 reveals little ideological division between MHRs. Fox told Parliament that ‘the time has come when we should again recommence the great work of colonising New Zealand, and the object of the Government proposals is, if possible, to re-illumine that sacred fire’. William Gisborne, who had stepped up from being departmental head to Colonial Secretary, declared that by colonising the country ‘the political distinctions which now divide district from district will melt away and disappear as morning mists before the light and warmth of the sun’.54 All this was heady stuff. Politicians, for the most part, were simply dazzled by the optimism and daring of Vogel’s artificial gold rush. The Otago Daily Times enthused that ministers had ‘caught the popular tone, and have pitched their proposals in unison with it’.55 When the policy was announced the usually cautious New Zealand Herald observed:

The policy of borrowing, and that largely, for public works in a young and undeveloped country like New Zealand is undoubtedly a wise one. Without these public works the known but hidden, and as yet unproductive wealth of the colony cannot be made available, and as the benefit accruing from works such as are proposed … namely main trunk roads and railways, will be permanent and lasting – it is perfectly equitable to the present and the future to spend the cost over a considerable period.56

Some settlers sensed that Vogelism would be the final coup de grâce for Maori insurrection.

William Fox, Premier 1869–72; and Sir Julius Vogel, Colonial Treasurer as well as Premier in the 1870s: Vogel was a man with bold expansionary views about the role of the State. ATL G-1322-1/1; F-928981/2

The only resistance to borrowing came from a handful of politicians who feared that Vogel’s ‘largesse … may be mismanaged’ and from the Wellington Evening Post. It was certain that the ‘ignorant and deluded’ would be sure to waste the money.57 Former premier Frederick Weld, now Governor of Western Australia, was also sceptical. He sniffily described Vogelism as ‘the gambler’s stake played by one who personally has nothing to lose, on behalf of others who have’.58 The wider public, however, had no such qualms. Having seen the Government fight a war, provide for veterans or their widows, sponsor immigrants and promise to find them employment, they expected the Government to be able to conjure up prosperity as well.

Borrowing on the London market was an essential aspect of Vogelism. By 1870 the country’s public debt amounted to £8 million, of which £3 million had been borrowed by the provinces. Vogel proposed to raise another £10 million over ten years in the belief, as Keith Sinclair puts it, that ‘money, men and public works’ would develop the country ‘at an unprecedented pace’.59 The Treasurer was soon back and forth to Australia, and twice travelled to London in search of loans. Two commissioners, F. D. Bell and Dr Isaac Featherston were despatched to London for the specific purpose of promoting rapid immigration to New Zealand.60 In 1871 Featherston became Agent-General in London. He was given wide discretion to offer assisted passages to an initial 8000 immigrants. Urgency governed his activities; central government was in no mood to indulge the provinces’ quibbling about their traditional role in the migration process. When Featherston’s quota was unfilled by the end of 1872 he was empowered to offer free passages as an inducement.

On 11 October 1873 Premier Vogel took over as Minister of Immigration. Using the cable facilities already in place from Melbourne to London, he told Featherston not only to pay for passages but to contribute towards migrants’ travel to the port of embarkation. Should it be necessary, Featherston could provide clothing for the voyage as well. Vogel wrote to the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union: ‘the position of a prosperous farmer is open to the immigrant who lands on the shores of New Zealand, no matter how poor he may be, if he is only gifted with temperate habits, frugality and industry’.61 It was scarcely surprising that many immigrants took these promises from the premier and his agents as a guarantee of success in the new land. The concept of a ‘social contract’ was gathering momentum.

Composition of Exports, 1853–1913. From Simkin’s Instability of a Dependent Economy

The peak period for immigration was 1874-75, when 31,000 people arrived in New Zealand over a twelve-month period. Of the 490,000 in New Zealand at the census of 1881, about 100,000 had come during the 1870s with various forms of assistance, most of it provided by the Government. Many immigrants were agricultural labourers, shepherds, navvies for the railroads, mechanics and domestic servants of good character. Others had more dubious backgrounds, leading Voge’s former paper, the Otago Daily Times, to denounce one shipload as ‘certificated scum’.62 This verdict was strongly refuted in later years by the historian Rollo Arnold. But there can be no denying that many immigrants expected that the Government which had assisted them to come to New Zealand would help them adapt to it. Vogel himself became worried about the lavish promises made to would-be immigrants by English agents, and in a series of letters to the Agent-General from September 1874 advised him to be more cautious, especially with promises of easy access to land. But by that time many inducements had already been offered and taken up.63

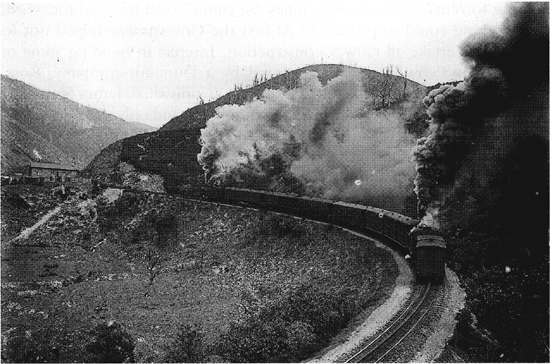

Central government’s sponsorship of colonial development was the central feature of the first half of the 1870s. Railway construction progressed apace. A few years later an Australian observer noted: ‘As if by enchantment, an eruption of… railways broke out all over the two islands. They cut their way through the densest scrub, they ran up steep hills, they spanned roaring torrents, and lept over gullies. Sir Julius Vogel had said the word, and nothing could stop them.’64 At first the Government hoped not to have to undertake all railway construction. Interest in building some of New Zealand’s railways was expressed by a Dunedin company, Ross, Hotson, Peyman and Walker, and by a Nelson individual, James Sims. The Government was cool to the Dunedin consortium and only slightly warmer to Sims, probably because it feared that neither possessed the resources to construct at the speed which ministers required.65 When he was in London in 1871 Vogel talked to John Brogden who had built the Auckland-Drury line in the 1860s. Six contracts were entered into. But Brogden’s base was 12,000 miles from New Zealand. He moved cautiously. Moreover, the provinces became querulous over their construction rights, which threatened further delays. Other considerations worried Vogel too. The realisation that some essential lines would not necessarily pay their way quickly, and that construction, if left to private enterprise, could result in a variety of gauges as in Australia, helped convince him that the State should take total control of the whole railway programme from design through to the operation of services.66

In the end, the need for speed was probably the biggest factor in determining the State’s paramount role. With so much money being borrowed, ministers could not afford to dally. Immigrants were soon pouring into the country in search of promised jobs. The Government was nervous. There was no time to waste on lengthy negotiations with distant contractors. Political considerations simply removed from the equation any serious prospect that New Zealand’s railway building could be undertaken by private enterprise. In 1886 when the Stout-Vogel Government was short of money, a contract was entered into with a private London-based company called Midland Railway. It was a land grant project whereby, in return for construction of a line from Springfield in Canterbury to Brunnerton on the West Coast and thence to Nelson, six million acres of land would be granted to the company. Each time a section of the line was opened for traffic, blocks of land could be subdivided and sold to offset construction costs. Like Brogden, Midland’s London directors were cautious. On 27 May 1895 building of the Midland line was taken over by the Government. A lengthy process of arbitration then took place over compensation. This experience simply confirmed politicians in the wisdom of their earlier decision to have the Crown build and operate lines. By 1900 only 88 miles of private line still existed, and in 1908 the last private line (between Wellington and the Manawatu) was taken over by the Government.67 An observation by a Government Railway Commissioner in 1894 summed up some of the issues facing the Government:

Railways creeping across difficult terrain: a trip to the Wairarapa about 1905. ATL G-341-1/2-APG

Had the building of railways been left to private enterprise, there is little doubt that the colony would not at this date have been so well supplied with the means of communication which have proved so large a factor in its advancement. The construction and working of the lines by the State seem in new communities to be a necessary preliminary to the development of [their] resources, for private undertakings are to a great extent controlled by the expectation of immediate returns, which in the case of the State can well be deferred so long as collateral advantages are being obtained in other directions.68

Instead of private enterprise, the Public Works Department, formed in 1870, designed and built most of the lines. Ministers specified the track to be laid – which occasionally led to accusations of political favouritism -then commissioned their construction. Gauges were standardised at 3 feet 6 inches, which made investment go further although the trains were slower.69 The Government’s construction costs in the early stages were deemed reasonable; the average cost per mile at £7,703 was more than the £3,531 per mile of the very first lines constructed, but below the cost of some private lines such as the Wellington-Manawatu line at £9,187. Reasonable construction costs enabled fares and freight rates to be kept down. A later Minister of Railways, Sir Joseph Ward, was able to crow in 1905 that the Government’s railways were returning 3 per cent on the capital cost of construction,70 although it should be added that after 1896 the Government did not oblige them to include interest on the money borrowed for construction. It was argued that railways existed not to earn profits but ‘to assist the development of the country’.71 This exemption gave the railway accounts a rosier glow than they deserved, and was not corrected until 1925. Nevertheless, in the early days of state construction, the public sector could often post results that seemed satisfactory, something which, over time, led to complacency and ultimately to a fall-off in performance.

To the 65 miles of line open for traffic in 1872 was added another 1107 miles by 1879-80. By then nearly three million passengers and more than one million tons of freight were being carried each year. Twenty years later there were 2235 miles of line in operation, carrying 6.2 million passengers and 3.4 million tons of freight.72 By the end of the century railways had long since replaced coastal shipping as the principal communication artery of the country. They provided the first links that drew the struggling provincial economies into a wider national entity.

Roading construction also sped up after 1870. Initially a sum of £50,000 pa was earmarked for distribution to provincial roads boards for constructing roads to outlying districts. At least £8.3 million was spent by the Government on roads and bridges between 1870 and 1900, with many of the early construction workers being Vogel’s immigrants.73 There were flow-on results from all this activity. Migration itself created jobs. Carpentry skills were much in demand to house the new arrivals. By use of legislation and orders-in-council issued mostly under the Immigration and Public Works Act and the Native Lands Act 1873, central government drove infrastructural development at a speed that sidelined critics and private competitors.

By the late 1870s most ports enjoyed regular shipping links and were tied to their hinterlands by rail. Telegraph, too, soon demonstrated its usefulness in bringing the provinces together. It was used to pass military information in the later stages of the war. Parliamentarians became regular users of the new service. As with railways, early provincial erection of telegraph wires was in the hands of private contractors, some of whom continued briefly to own the lines.74 But central government’s needs, especially during the war, seem to have provided the impetus for establishing a Telegraph Department. A. C. Wilson notes that ‘by the middle of the 1860s the Department had become the major player in the country’s [telegraph] network’.75 When the provinces backed out of public works because of a shortage of funds after 1867, private interests sold their completed lines to central government and ceased further construction. Publicly built lines were swaying across the country by the late 1860s. Communication was established between Auckland, Wellington and the South Island in 1872. In 1874, steps were taken by the congenitally optimistic Vogel to lay a telegraph line over the ocean floor to New South Wales. It began transmission in 1876 and had the direct benefit of connecting New Zealand with Great Britain. Two years later the first internal telephone demonstration was staged between Nelson and Blenheim. By 1900 connections were proceeding apace and there were nearly 8000 telephones in the country.76 Political considerations simply pushed private enterprise aside.

Many economists and historians have endorsed Vogel’s centrally driven economic extravaganza. Most have called it right for the times, and noted beneficial effects from Vogel’s actions. Gary Hawke claims that real income probably grew in the 1870s as a result of Vogel.77 In 1986 when reviewing a biography of Vogel, the then Minister of Finance, Roger Douglas, remarked that Vogel was correct to stress the development of New Zealand’s infrastructure in the 1870s: ‘without basic transport and communications and without large-scale immigration, the potential wealth locked up in New Zealand’s hinterland would have remained locked up a lot longer’. Douglas noted, however, that Vogel’s propensity for large-scale borrowing was to live on in New Zealand’s political folklore, and be applied in later circumstances that were not so likely to produce beneficial outcomes.78

Provincialism was sidelined by central government’s public works programmes. It became the major casualty of Vogelism. Since it was now possible to talk of a growing national entity rather than a group of scattered, unconnected settlements, the now nine provinces had outlived their usefulness. Harry Atkinson, who was Premier by the time they vanished, expressed the view that ‘a very large saving [would] ultimately be made by the amalgamation of the general and provincial services’. The Abolition of the Provinces Act 1875 came into force on 1 November 1876. It vested the powers and property of the provinces, described by Atkinson as ‘nine sturdy mendicants’, in the central government.79