Historians have underestimated the significance of the abolition of the provinces. By that act the developing colony abandoned the possibility of a decentralised structure; the administrative changes of the next two years vested in central government many of the functions formerly performed by the provinces. The transfer occurred at a time when the New Zealand economy was beginning to subside after several hectic years of Vogelism. A mounting fiscal crisis reinforced the trend to centralism as a procession of Colonial Treasurers grappled with declining revenue and high interest payments on Vogel’s borrowed money. It was another twenty years before economic recovery looked permanent. In the intervening years politicians were obliged to consider the rights and responsibilities of individuals, and the roles of local authorities and the State. For the first time there were sustained debates among New Zealand’s leaders about British theories and practices, and their application to New Zealand conditions. As a result the State’s activities were intensified rather than wound back.

In 1876 it seemed as though some savings could be made by abolishing provincial bureaucracies. Atkinson’s Government pensioned off 102 provincial officials. However, new constitutional structures had to be created. They were municipalities, counties, road and river boards. No guidelines were provided about size. Small, parochial units mushroomed, encouraged by the fact that in the Financial Arrangements Amendment Act 1877 the Government agreed to pay a £1 subsidy for every £1 collected in property rates by local authorities. Further subsidies were added over the next three decades. Local authorities were receiving nearly £120,000 directly from the Consolidated Fund by 1906, much of it intended for roading. Elected special purpose boards were gradually added to the initially simple local structure in the years after abolition. Eventually the Premier, R. J. Seddon, complained that every second man he met seemed to be a member of an elected public authority. The first substantial effort at local government reform began in 1895, but the multiplicity of authorities defied a century of reformers. Substantial changes did not occur until October 1989.1

A major logistical exercise was involved in centralising education and health after 1876. Substantial government funding was at stake, so careful thought was required. Demands for assistance with education were common after 1840. Missionaries lacked the resources to educate all Maori and Pakeha. Subscriptions to private schools were not numerous since most of the wealth possessed by settlers was tied up in their land, and not easily accessible for social purposes. Grants were made from both central and, later, provincial governments. Money was short in Canterbury because of the New Zealand Company’s financial woes. Provincial politicians soon reconciled themselves to taxing to finance education.2 In Wellington private and church organisations had rather more success running schools, but by the end of the 1860s their systems were breaking down from lack of funds. In 1871 the Wellington Provincial Council took over the organisation of primary education in that province.3 In Dunedin in the early 1860s, when citizens banded together to form benevolent societies to assist the poor to educate their children, they too asked for help from public authorities. In 1864 Otago’s provincial government began a ‘Ragged School’ in Stafford Street. Within a short time it had a roll of 80 youngsters from deprived backgrounds. Five years later cooperation between provincial and central governments was necessary before New Zealand’s first university opened its doors in Dunedin.4

By 1876 some parts of the country such as Canterbury and Otago possessed reasonably efficient educational systems. In others, as the new minister, C. C. Bowen lamented, there was nothing at all.5 A majority of parliamentarians favoured the State establishing a universal system of primary schooling, and this was incorporated in the Education Act 1877. Government money on a per capita basis was channelled to these schools through regional education boards. Two years later, 1773 teachers were on the State’s payroll. They were teaching 75,666 students in more than 800 schools. State support dropped away once a child left primary school. There were only ten high schools receiving state supplements. This money was paid on top of fees, which approximated £10 each year for a child. A handful of talented children got into high schools because they won scholarships. These entitled them to free tuition. A separate system of Native Schools was also set up and subsidies were paid to ‘industrial’ and other schools catering for special needs, or problem children. Inspectors became an integral part of the system. They reported directly to boards and to the minister.6 The University of New Zealand, which was established by an act of Parliament in 1870, also received a grant from central government. By 1876 the University of New Zealand had two campuses, Otago (1869) and Canterbury (1873). Auckland (1883) and Victoria (1897) joined the national network in later years. As with high schools, it was expected that fees would supplement the Government’s grant.7

Foxton School in the Manawatu County, March 1878. ATL G-344-1/1

Education soon became a major item in the Government’s budget. In Bowen’s view, he who paid the piper called the tune: ‘It is absolutely necessary … that, where this Parliament supplies the larger part of the funds, it should retain the ultimate regulation and control’, he told Parliament.8 Not surprisingly, schools, private as well as public, always wanted more assistance. The annual reports of the Minister of Education contain special pleading from anxious boards and hungry educationalists. Lobbying by public service providers came early to New Zealand.

Health care provided a similar challenge in the post-provincial era. Hygienic conditions were nonexistent in many early towns. This contributed to sanitary problems that public authorities, local as well as national, dealt with in an ad hoc manner. Hobson allowed prisoners to be used to clean up Auckland’s filthy Ligar Canal in the early 1840s, yet by 1847 Auckland ‘ha[d] enough filthy lanes and dirty drains to keep up a perpetual plague’.9 Public health was one of the first concerns of the local council elected in 1851. Anxiety about typhoid and other diseases among Maori in the Wellington region influenced Grey to approve the construction of a Colonial Hospital. It opened its doors in Pipitea Street in September 1847.10 Central government often felt obliged to fill vacuums that existed in provincial services. Round the swamps of North Dunedin, where prospectors camped on the way to the goldfields, the squalor, disease and misery cried out for intervention from those in public authority. Erik Olssen observes that the mortality rate among Dunedin children exceeded that in England. The Otago Provincial Council felt it had no option but to act; in 1864 the council appointed a Sanitation Commission. The commissioners reported an urgent need for clean water. The Council decided to subsidise private efforts to supply clean water. For a time commissioners tried to run what was in reality a private company. Providing water did not prove profitable and in 1875 private interests surrendered their involvement to the Dunedin City Council. It also began supplying gas when a private company failed in 1871.11 Long before the abolition of the provinces, public authorities were being obliged to intervene in areas where private or even charitable institutions would probably have shouldered the burden in the ‘Old Country’. No one else had enough resources to do what was needed on so many fronts at once.

Between 1852 and 1876 the provinces were responsible for general and mental hospitals, and provided charitable aid as well. After 1872 local boards of health met occasionally within each of the provinces. Central government was responsible for the appointment of port officers of health and public vaccinators. In 1876 a Central Board of Health was established. It met when an emergency arose. Funding of hospitals was provided on the same basis as had applied under the provinces. In the Financial Arrangements Act 1878, the Government formalised a subsidy regime for maintaining hospitals. Some hospitals deemed of special importance received two thirds of their monthly expenditure, others only half.12 Areas with an existing hospital board were obliged to raise their own money if they wished to expand facilities. Hospitals were told that they must collect money from those patients who could afford to pay. The money should preferably be gathered in advance of treatment. ‘Pauper patients’, the Colonial Secretary informed the Timaru Hospital Committee, ‘will of course only be admitted on proper proof of their poverty.’ The Colonial Secretary’s office became a claims centre. Each year it handled hundreds of inquiries from boards and issued cheques to them. It handled requests for new buildings, and agreed to salary increases for staff. In January 1878 the Colonial Secretary was even invited to intervene when attempts were made to commandeer the surgeon’s sitting room for medical training at Christchurch Hospital.13

One factor in the Government’s desire to share hospital costs with local authorities was a belief that they were better placed than any centralised authority to monitor expenditure. The Under-Secretary to the Colonial Secretary, G. S. Cooper, told the Mayor of Christchurch in 1878: ‘It needs no argument to show that local supervision at the hands of those who have a direct interest in seeing to the efficiency and economy of the management of [hospitals] can alone effectively ensure the attainment of these ends.’ Cooper suggested that councils might care to take over the management of hospitals.14

However, when the economy began contracting in the late 1870s, calls on local authority revenue increased rapidly. On 1 April 1881 many councils ceased providing money for local hospital maintenance. The Government felt an obligation to fill the gap. But its own revenue was also under strain. Ultimately, passage of the Hospitals and Charitable Institutions Act 1885 gave the Government authority to devolve revenue-raising on to 28 hospital boards. Government subsidies payable on locally collected funds were reduced to ten shillings for every pound raised. Local authorities were obliged to play a larger role in maintaining their hospitals.

After the abolition of the provinces health special pleading became commonplace. A careful reading of official correspondence reveals that parliamentarians were soon putting pressure on ministers to provide more for their areas. In 1883 Wellington Hospital was asked to expand its number of days for treating outpatients. A few years earlier, the Colonial Secretary’s office had been astonished to discover that the Government was obliged to pay a £2 for £1 subsidy as a result of promises rashly made in Tuapeka by the Colonial Treasurer during the 1879 election campaign.15 ‘Politically driven’ hospitals were an early feature of New Zealand life. The rules governing funding could always be bent under pressure, something that continued until the principle of ‘equitable funding’ of hospitals was introduced in 1983.16

A mix between central and local funding of hospitals lasted until 1957, when the Government assumed responsibility for all public hospital costs. During the intervening years an increasingly centralised system developed, with governments paying a growing proportion of total costs. When the Board of Health proved itself ineffective in combating the arrival of bubonic plague in New Zealand in 1900, the Colonial Secretary, Joseph Ward, created the Department of Health. It was the first such centralised health authority in the then British Empire. Initially the department concentrated on ensuring better sanitation, clean water and sewage disposal, and dealt with quarantine matters. Some local authorities resented central intrusion, but their objections were brushed aside. In the Hospital and Charitable Institutions Act 1909, 36 hospital districts were established, each with an elected hospital board. Psychiatric institutions continued to be administered centrally, first by the Department of Education until 1911 and then by the Department of Health. In 1972 they, too, were transferred to hospital boards’ jurisdiction, and were funded out of the Government’s block grants.17

The early insistence that locals should shoulder some responsibility for services lay behind the post-provincial approach to the destitute. Expecting families to support them worked only where there were families and they agreed to cooperate. Parliamentary debates about indigence in the 1870s turned around three options for the future: sharing the costs of poor relief between central and local government, having the State pay all the costs, or introducing a ‘poor rate’ at the local level. In the end a majority favoured sharing costs.18 Complex negotiations took place between the Colonial Secretary and the Mayor of Wellington in early 1877; the resulting agreement became the funding basis for the rest of the country. Benevolent societies were soon receiving grants on a pound for pound basis. A ‘Female Refuge’ in Christchurch, a ‘Home for Friendless Women’ in Wellington, an orphanage in Christchurch and an ‘Old Men’s Refuge’ in Auckland received assistance from the Government.19

These administrative changes at the end of the 1870s greatly enhanced the power of central government which, by now, was taking a close interest in most developments within the colony. Private endeavour also came under its scrutiny. The Colonial Secretary’s incoming mail reveals that entrepreneurs interested in activities as diverse as the development of inter-provincial coach links, coal and oil exploration or the staging of a local exhibition first sought financial assistance from the Government. There were requests for help from people wishing to attend, or display goods at international exhibitions. The notion that private enterprise had an entitlement to socialise their early development costs, the better to capitalise later gains, was a philosophy that inspired New Zealand entrepreneurs for another century.20

Vogel’s economic pump-priming produced its best results in 1873. Thereafter the economy subsided. Meantime, immigrants were pouring into the country. The capacity for both the public and private sectors to provide employment soon flagged. In the lead-up to the general election of January 1876 politicians found themselves under heavy pressure to prime the pump.21 Much of the next decade was spent coming to terms with the flow-on effects of Vogel’s hubris. Political coalitions came and went; those of Harry Atkinson (1876-77) and John Hall (1879-82) tended to be more cautious borrowers. Sir George Grey’s (1877-79) purported to be a reform administration and borrowed another £5 million. But with these loans came a condition: since its net public debt stood at £21 million, New Zealand must stay clear of the London market for a further three years. Grey’s Government spent much of its time tending to the brittle fortunes of urban speculators in its midst, rather than dealing with rising concern about unemployment.22 A land tax on larger estates was introduced, angering most farmers who now liked to picture the premier as a tool of urban moneylenders heading a government of ‘sound and fury’.23 New Zealand politics was entering the stagnant, vituperative 1880s.

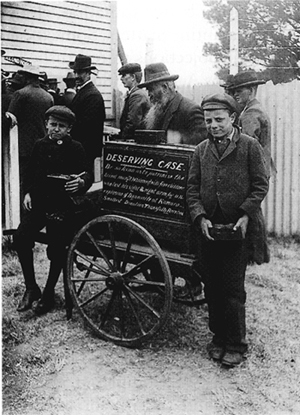

Early charitable aid: two Yugoslav lads soliciting help for their father on the West Coast, late 1880s. ATI., Steffano Webb Collection, G-49635-1/2

Atkinson became Colonial Treasurer in Hall’s Government in October 1879. He endeavoured to reorganise the country’s finances by reducing waste and lowering colonists’ expectations. A Royal Commission into the public service was appointed in March 1880. It was chaired by Alfred Saunders, a journalist, farmer and politician, with some pretensions to being a historian.24 The report’s sweeping assertions shocked many. The commission described ‘an aristocracy of Government officials’ who enjoyed substantially better conditions than those in the private sector. One adult male in every thirteen in the colony (a total of 10,853) was directly or indirectly on the Government’s payroll. The Saunders Commission called for ‘heroic sacrifices’. Asserting that governments had ‘fostered unreasonable and unattainable expectations’, had inflated wage rates and had artificially influenced the development of resources in the country by a decade of activism and ‘reckless spending’, it recommended that the cost of government be reduced ‘without impairing or lessening its efficiency’. So startling was the report that the Government seemed unwilling to believe aspects of it, and little was done to implement its recommendations.25

Another royal commission was appointed in March 1880 under the chairmanship of J. W. Bain, a conservative Southland identity. He also favoured less government intervention in the economy. The Royal Commission on Local Industries sought to tackle head on the arguments being advanced for higher tariffs by those who believed they would stimulate job creation. It recommended great caution when making changes to customs dues except when they were revenue measures and applied across the board. The Government should be careful ‘lest, for the sake of hastening the prosperity of a particular industry, or affording special advantages to a particular section of the community, a blow should be unintentionally but none the less effectually struck at other industries in the prosperity of which all sections alike are interested’. The report favoured no tariffs on raw materials, and only sparing use of them on finished products.

Echoing comments that were being made in Australia at the time, Bain’s Commission expressed the opinion that high wages in New Zealand were a big factor militating against the successful promotion of local industries. However, while the commission opposed tariffs, it was not against direct government support to selected industries. It built on the recommendations of the parliamentary committees of the 1870s, recommending monetary incentives for home-grown tobacco, sugar, linseed oil, silk and starch, and active encouragement of honey production. While commissioners doubted whether the iron industry had yet reached a stage where bonuses were warranted, maximum effort should be made to ensure that locally produced coal was used as a fuel ‘because it enters more or less into the economy of every local industry in the country’. The report drew attention to the dominant role of the State in public works construction, noting that inflated wages were luring skilled workmen away from private firms. In effect the Bain report argued for a level playing field for wages. It was a perceptive contribution to a debate that would rage for another century.26

The Government’s fiscal crisis stimulated political thought and the propensity for further state experimentation. Atkinson’s efforts in 1880 did reduce expectations. But the notion that governments had something approaching a solemn contract with colonists to use resources for their direct benefit did not wither so easily. From the earliest days of colonisation central government felt a degree of responsibility for the welfare of the waves of settlers that came to New Zealand. Migration was the result of both carrot and stick. It was not just the privations of industrial Britain that drove people to travel half way round the world. They needed incentives as well, such as the prospect of land and opportunity. Most liked the thought of a fresh start in life. A sense of adventure could propel young men, especially if much, or all of the passage was paid by the Government. When El Dorado failed to materialise, and people found themselves out of work, they grumbled. John Martin observes: ‘The unemployed considered that they had a social contract with the government, who by bringing in immigrants should also provide them with work in times of need’.27 Grievance politics was an early part of New Zealand life. It thrived during the long depression, helping ultimately to drive further state expansion.

Settlers had some cause for dissatisfaction. The New Zealand Company had been careless with its purchases; ‘land jobbers’ and absentee owners bought up large tracts, forcing up prices; often short-term employment was all that was on offer when many settlers expected something more permanent.28 Disease and accident did their part to make settler life far from ideal. Fires or floods could destroy livelihoods in a few minutes. Many had no family to turn to in distress.29 Desertion of wives and children was not uncommon, and alcoholism plagued frontier societies in all parts of the world.

Debate over public provision of welfare was probably less intense in colonial societies than in Great Britain. Traditional lines between state and private responsibility ran deeper in Britain and charities were more numerous because there was more private wealth to tap. Most of New Zealand’s early politicians had brought their British attitudes with them. Hobson granted aid to indigents with reluctance. Margaret Tennant reports that several ‘self help’ institutions in the form of lodges and friendly societies had been set up in New Zealand as early as 1841. Yet they were of benefit only to those in permanent employment who could pay regular premiums. A crisis was averted for many years because the early settlers were so uniformly young that problems of sickness and age did not show up on the same scale as in the British Isles.30

However, by the late 1870s the mounting costs of social services began to worry governments. The ageing process was catching up with many of the original settlers at the time of economic downturn and there was unease in political circles. During the parliamentary session of 1875 members debated the need to encourage more thrift. Much on their minds was the need to raise the numbers of workers investing in friendly societies so that they could benefit from sickness and retirement entitlements. In June 1876 the Colonial Secretary, Dr Daniel Pollen, introduced a bill to require friendly societies to submit annual returns of their accounts to a registrar. Supporters of the Government enthused about the work done by friendly societies and the need to protect those who joined them. The Bill failed to pass; MHRs wanted more time to study the issue. A few complained about ‘government interference’ in private contractual arrangements.31 In July 1877 the Friendly Societies Bill was back in Parliament with modifications after ministers had studied similar British legislation. This time there was little debate; the Bill passed without a division. Ministers hoped that by ensuring a greater degree of friendly society accountability to their members, confidence in them would rise, more people would join, and requests to Government to help those in need would be reduced.32

Within eighteen months of the passage of the Friendly Societies Act, 123 societies had complied with its requirements. But membership of friendly societies did not keep pace with the population growth. Moreover, as David Thomson has shown, many of the societies were actuarially unsound, promising more than they could possibly deliver from the premiums paid.33 Atkinson began casting about for further detail on overseas self-help schemes. He concluded that the Government could not afford to pay for the growing incidence of poverty and that it was necessary to compel people to insure themselves against possible misfortune. On 10 July 1882 he introduced a National Insurance Bill. The Bill turned the concept of voluntary insurance into a compulsory system. According to Atkinson it was impossible to rely entirely on benevolent institutions, hospitals and charitable aid. They were ‘temporary palliatives’. Friendly societies, while admirable, reached too few people. Individuality and independence could best be maintained if all employees were levied £8 per year and the money paid into a general national insurance fund. ‘The only effectual remedy against pauperism seems to me to be not private thrift or saving, but cooperative thrift or insurance, and that, to be thoroughly successful … must be national and compulsory,’ he said. The State would use rents from the Government’s leasehold land to support widows and orphans who could not afford to pay their premiums. As a safeguard against those who might ‘rip off’ the system, lists of recipients of sickness benefits would be posted outside each local authority. People would be invited to inspect them and report ‘malingerers’.34

Atkinson in later years had the reputation of being a conservative. He regarded himself as a ‘liberal’, while others painted him as ‘an ardent socialist’.35 Atkinson made it clear that he was not opposed to an activist State:

In this country the Government has already done many things which fifty years ago the greatest Radical would probably have declared beyond the functions of Government. We have State railways, State telegraph, State post office savings-banks, and … State education, all of which in their turn have been declared entirely beyond the proper functions of Government, and ruinous to the independence of the people who adopt them. But I will point out this fact: that nothing can be done nowadays without combination … if we can promote the well-being of the people, – if we can really strike a fatal blow at pauperism, - then this matter is clearly within the proper functions of Government.36

There were two interesting aspects to the debates of 1882. The first was a general unease about the lack of settler frugality. Many seemed to expect help in times of need, but were not prepared to insure against hard times. Atkinson, at one point commented: ‘We know, unfortunately, that the majority of men are either unthrifty, careless, or of such a happy-go-lucky disposition that they do not make proper provision for the morrow.’37 He and his supporters believed that the State must be paternalistic, and do for settlers what they appeared unwilling to do for themselves. The second interesting aspect to the debate is the difference of opinion about how, precisely, the State should intervene. Atkinson wished to maintain the principle of people contributing equally towards their own ultimate benefit. As he described it, he would ‘saddle the cost of the system upon the men who will use it hereafter’, adding that if that was ‘an interference with the liberty of the subject which a civilised man can complain of, then I do not understand the meaning of civilisation’.38 In today’s parlance, Atkinson believed in a rough and ready form of’user pays’.

Sir George Grey, on the other hand, worked himself into a lather over Atkinson’s proposals. It is far from clear whether Grey was completely opposed to national insurance. As his speech progressed he made several interesting comments. ‘A man will not watch his neighbour when he is getting Government money in the same way as he would watch him if he were an independent member of society. The payment [from] the Treasury is so distant from the man … that it does not produce the same effect on his mind…. [Atkinson’s] plan will have the same effect of sapping all the finer elements of our nature.’ It can be inferred from this observation that Grey favoured a personalised scheme of national insurance more akin to the New Zealand Superannuation system adopted briefly in 1974. But having made his observation, Grey veered away, saying that if there were to be any form of national insurance, then he favoured it being funded through general taxation – where the benefits, of course, were even further removed from the contributors! Grey insisted that the propertied should pay most towards helping those in need. Grey’s speech was an early version of the ‘soak the rich’ approach to funding New Zealand’s welfare policy. It helps explain why some of the more advanced Liberals of the 1890s regarded Grey as their elder statesman, and why in 1900 the Government willingly contributed £1,000 towards a statue of him in Auckland.39 The arguments that were canvassed in 1882 contained many of the ingredients of a debate over the welfare state that would rage for a century to come.

Atkinson’s Bill was ahead of its time. Many MHRs did not take it seriously. There was no vote, and no system of national insurance was established. The State carried on contributing towards the growing incidence of ‘pauperism’ out of the Consolidated Fund. Assistance was extended to several thousand people in the mid-1880s through what was called ‘outdoor relief provided by public hospitals that doubled as charitable-aid boards.40 There was no mood to increase taxation as envisaged in Atkinson’s scheme.

The depression of the 1880s deepened. Borrowing in London was possible only intermittently. By 1888 the country’s net indebtedness stood at £35.4 million for a population that numbered only 600,000.41 A frozen meat market in London opened up after refrigeration was first used in 1882 for shipping meat. However, meat prices collapsed in 1887. Immigration tailed off. Circumstances now forced severe retrenchment on to reluctant governments. Unemployment steadily increased. More work camps were set up on the edges of towns where men were paid four shillings a day. A total of £22,246 was paid out in government grants to unemployment schemes between 1884 and 1887.42 William Rolleston, who was Minister of Lands 1879-84, promoted what came to be known as ‘village settlements’ for immigrants. His scheme allotted sections ranging between one half and two acres that were near railway lines. Without village settlements, Rolleston declared, there would be ‘a floating population wandering about the country, having no interest in the Colony and never becoming good citizens’.43 Both John Ballance during the Stout-Vogel Ministry 1884-87 and Atkinson later in the decade promoted variations of Rolleston’s scheme. Nothing, however, could stop a net outflow of settlers from New Zealand which was under way by 1888. The implied contract between immigrants and a now impecunious State, was fracturing badly.

As desperation set in, the Government reflected the popular mood. Saddled with office in 1887 for what was to be his last term, Atkinson and his ministers in the ‘Scarecrow Ministry’ were battered about by an increasingly articulate group of opponents. They were beginning to call themselves ‘Liberals’ and seemed intent on using the powers of the State to increase job opportunities. Some of those who gathered around John Ballance in 1888 appeared to acknowledge a degree of responsibility for immigrants to whom earlier promises of employment had been made. Others knew that expressions of concern were good politics. Preserving jobs for settlers was a strong theme underlying the debates in 1887-88 on restricting Chinese immigration. Pushed along somewhat against his will, Atkinson agreed to a poll tax of £100 to be paid by all Chinese immigrants. Further restrictions were imposed in the 1890s and early 1900s.44

When Atkinson felt obliged in 1888 to increase government revenue by taxing items such as tea, his Customs and Excise Bill became the plaything of those with more radical inclinations. Tariff protection for New Zealand industries had been advocated by several protection leagues for many years and was proposed by the Stout-Vogel Ministry before its defeat in 1887. Proponents believed that protection would increase the number of jobs.45 Atkinson scorned tariffs intended for purposes other than revenue. Faced with a depression, however, MHRs with urban constituencies where the unemployed tended to congregate, willingly embraced protection. Increases of from 5 per cent to 25 per cent were imposed, with an average duty of about 20 per cent on all imports. They effectively doubled existing customs duties on many items.

Despite MHRs’ intentions, there is doubt about how much these tariffs assisted the gradual increase in manufacturing output that took place after 1888.46 However, a precedent had been set: New Zealand was now committed to moderate protection against the better judgement of farmers, who saw tariffs as favouring urban workers at a cost of raising import prices. Social engineers were cock-a-hoop, seeing tariffs as a cure-all for the economic ills of the day. The new Christchurch parliamentarian, William Pember Reeves, expressed their views succinctly: ‘Holding as I do that a protective tariff is the greatest benefit that a Government can possibly offer to the people of New Zealand just now, I accept this measure with gratitude…. We want outlets for capital; this tariff will provide them. We want employment for our working people: this will give it. We want something to check the exodus of population; this will check it.’

Some outside observers such as Andre Siegfried thought the tariff was high enough ‘to allow the New Zealanders to settle for themselves the conditions of production without paying much attention to outsiders’. He was convinced that New Zealand’s pioneering labour legislation of the 1890s would not have been possible without the degree of economic insulation that the tariff provided. In effect New Zealand was passing another milestone in the growth of state intervention in the economy. But tariffs remained controversial, as disliked by the farming community as they were popular with manufacturers and trade unions. In the hope of placating the rural sector, the Liberal Government in 1900 exempted a large list of agricultural implements and machinery from the tariff, but other goods remained on the tariff schedule, defying intermittent efforts to remove them.47

John Ballance’s Liberal Party came to office on 24 January 1891 after Atkinson’s defeat at the polls the previous December. At the time neither party appeared to have a radical set of policies. A majority of adherents to the new Liberal Government had voted for protection in 1888, and for the abolition of multiple voting as well as the introduction of universal manhood suffrage the following year. This last measure increased the number of voters, and allowed men without property to vote. Many Liberal MHRs went further, supporting Ballance’s arguments in July 1890 that the abolition of the property tax, and substitution of it with land and income taxes, would be more equitable, and likely to increase land settlement which had slowed during the 1880s.48 Most Liberals accepted the evidence of’sweating’ of women and children in factories. They adopted a more moderate attitude towards the strikes of 1890 that were the first nationwide example of trade unionists flexing their muscles in industrial confrontation. Yet it was not support for the strikers so much as a wish to devise a way in which disputes between capital and labour could be amicably resolved that motivated Ballance’s supporters. If anything bound the Liberals together it was the fact that they were younger, newer immigrants with several first generation New Zealand-born politicians in their midst. They were all hungry for office and willing to use the power of the State to administer affairs in a manner that enhanced individual opportunities. They wanted no special privileges for any segment of the community. ‘Fairness’ became a word much in vogue.49

Caution reigned under Ballance’s two-year premiership; the Premier exhorted ministers to watch spending until revenue improved. However, there were signs that a new broom was sweeping in Wellington. Mindful of the urban dwellers, many of them Vogel’s immigrants who supported Ballance at the election, his ministry took steps to increase employment opportunities within the public service. Postmaster General, Joseph Ward, a dapper, entrepreneurial Irish Catholic from Southland, sensed that a reduction in postal rates would produce more work for the Post Office at little cost in lost revenue. He proved to be right. The posting of newspapers and parcels increased by 85 per cent in the first year of the new rates. Ward soon took the same gamble with telegram and telephone rates, again with the same result. Post Office work expanded rapidly, the Government’s revenue rose and staff numbers increased. As the economy slowly improved, the construction of roads, railways and bridges stepped up. When he became Minister of Railways in 1900, Ward tried his old trick yet again. He reduced rail charges. Patronage increased and extra revenue flowed into the Government’s coffers.50 The number of Railways staff rose steadily. After years of controversy over the route to be followed, the North Island Main Trunk line opened in 1908. By this time ministers had convinced themselves that state ownership of utilities was central to economic expansion. In his dual capacities as Postmaster General and Minister of Railways, Ward saw himself as the facilitator of private endeavour. In 1906 he wrote:

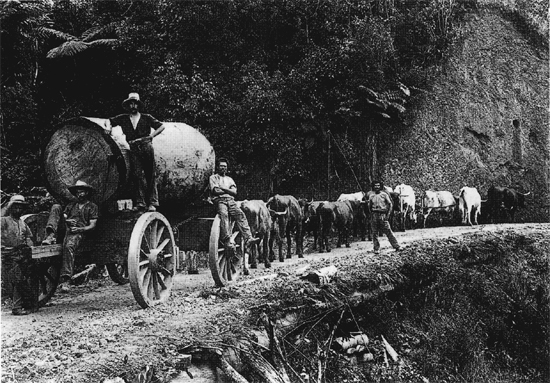

Liberal spending on roads helped open up remote areas; carting a kauri log out of the Northland bush at the turn of the century. National Archives

The duty of the State is to foster the industries of the country, cheapen the cost of transport, and by so doing to assist in funding profitable employment for the people and remunerative markets for the fruits of their labour, and there is no more efficient means to these ends than State ownership of railways.51

Public service numbers rose gradually during the 1890s, stepping up as new departments and services were added to existing ones. Many jobs were in remote parts of the country. However, for more than a decade Wellington enjoyed the fastest rate of population increase of any city.52 The Post Office employed 2225 people in 1890 and 7258 by 1912.53 Railways had 4116 people on its books in 1890. Numbers stood at 13,523 by 1912.54 There were 788 employees of the Public Works Department in 1891. These had risen to 5828 by the end of the Liberal era. The Charitable Aid Boards had been eyeing these three departments as a potential source of jobs since the early 1880s.55 They easily filled that role under Liberal patronage. Police numbers also nearly doubled from 492 in 1891 to 835 in 1912. Such raw figures tell only part of the story. The public service employed roughly 10,000 in 1890. The total number of people on the State’s payroll rose to approximately 30,000 in 1904 and stood at more than 40,000 by 1912. Housing the Government’s mushrooming public service provided construction jobs, particularly in the capital. While the public service rose fourfold, the population moved only from 634,000 in 1891 to 1.1 million by the time the Liberals left office.56

A job in New Zealand’s public service became synonymous with security. Ward introduced a variety of superannuation schemes for government workers, arguing always that the State had a duty to be a good employer. Beginning in 1893 with the Civil Service Insurance Act, there followed special schemes for post office and railway workers, and then teachers. Finally, beginning on 1 January 1908, a comprehensive retirement scheme for all remaining state employees came into force.57 Elementary schemes for top civil servants dated back to 1858 but the Liberals legislated for the ranks. Increasingly generous contributions towards superannuation entitlements were paid out of the Consolidated Fund by the Government. Employees contributed a fixed percentage of their wages to an increasingly complex pay-as-you-go scheme. It was small wonder that big departments requiring minimal skills such as Railways, Public Works and the Post Office always had waiting lists of people wanting employment.58 The Liberal Government made a valiant effort to fulfil the implied contracts that so many earlier immigrants believed they had with the Government that had brought them half way round the world.

It suited the Liberal Government’s electoral purposes to label their political opponents as conservatives and themselves as the architects of a new world of social responsibility.59 Ballance and his successor, Richard John Seddon, were good publicists for their cause. No occasion was too unimportant for a tub-thump from Seddon. With the extension of the franchise first to the unpropertied, then to women in 1893, politics became more folksy. Seddon’s inclusive style of politics was appropriate to the widening electorate. As in Great Britain, meetings and rallies became a form of mass entertainment.

The extent to which 1890 marked a watershed in the development of relationships between the people and the State will always be debated. As has been shown, successive governments with few genuflections at overseas experience or ideology had been pushing out the frontiers of government involvement in the New Zealand economy since the early days. The process began long before John Ballance came to office. However, under Seddon’s premiership (1893–1906) the Government’s role in the economy and in the provision of public welfare expanded rapidly. Some of the changes were forced upon the Government, others were the product of shrewd calculations by Seddon and Ward. Many came as the result of perceived political advantage. ‘Liberalism’, New Zealand style, came to mean pragmatic use of the State on behalf of any section of society deemed worthy of assistance by the ministry.

Occasionally the Government’s actions were pushed along by strongly held theories or attitudes imported from Great Britain. Jock McKenzie, who was Minister of Lands and Agriculture 1891–1900, was described by one of his critics as ‘a large, bovine, honest wrong-headed man’.60 Others worshipped him. Of Highlands origin, he hated the evils of land monopoly in Scotland and held passionately to a belief in small farming. He stepped up the rate of purchase of Maori land, acquiring several large estates. They were then subdivided into smaller units and let out to new farmers on Crown leases. In his reluctance to encourage the freehold, McKenzie echoed the views of Ballance and a former premier, Robert Stout.

The concept of leasing Crown land had been incorporated in legislation since 1882, but prior to McKenzie there had always been periodic revaluations. Many leaseholders also had the right to purchase their leases. However, McKenzie regarded land as an exhaustible resource which ought to remain as much as possible within the Crown’s estate. In a series of enactments he changed the rules. First he set about ‘busting up’ the big privately owned estates using new tax provisions. Besides introducing New Zealand’s first income tax for those with incomes exceeding £300 pa, the Land and Income Tax Act 1891 enacted a graduated land tax on estates worth more than £5,000.61 McKenzie pursued his goal more vigorously in the 1892 Land for Settlement Act. It empowered the Government to purchase suitable properties for leasehold purposes. In the more radical Land Act of 1892, the emboldened minister set out the terms under which settlers could gain access to new land that the Government was purchasing from Maori. No one could buy more than 640 acres of prime land or 2000 acres of ‘second class’ land. These sections could either be purchased for cash, leased at 5 per cent of the current value with a purchase clause to be exercised later, or leased in perpetuity for 999 years. Leases-in-perpetuity were to be at 4 per cent of Government valuation per annum, with no periodic revaluation or recalculation of the rent. Criticised by some as tantamount to the State providing what amounted to freehold land at cheap prices, they were popular with those who had little money but wanted to get on to the land. In the first two years of operation, nearly twice as much land was leased in perpetuity as was sold under the other two options combined.62

Openings of public buildings were gala occasions: the new Government Building at Bluff, 21 November 1900.

In 1893 McKenzie purchased the 84,755-acre Cheviot Estate in North Canterbury for £260,220. Much of it was divided up for Crown leases. In 1894 a further Lands for Settlement Act consolidated the lease-in-perpetuity although there was some criticism from within the Liberal caucus. The Act also introduced the power of compulsory purchase of land. This move led a few to fear that the Liberals intended to expropriate private property altogether. Whatever McKenzie’s initial intentions, a shortage of money hampered his use of the Act. The compulsory powers were seldom used. This was principally because, as Jim McAloon has shown, most large landowners sold willingly. They realised that divesting themselves of their large estates and investing the money in rural mortgages made better economic sense. ‘There was a broad consensus [among the wealthy] on the need to encourage and facilitate closer settlement and some of the richer… even professed to support compulsory repurchase of land by the state.’63 In the end, more than one hundred estates were purchased without compulsion. By 1909, 5174 tenants had taken up leases-in-perpetuity on smaller parcels of land that totalled 2.4 million acres.64

By the turn of the century colonists were competing vigorously to gain access to the rapidly dwindling supply of land. In addition to farming for wool, meat was regaining its earlier price level and dairy farming was proving increasingly profitable, particularly in the North Island. But there were many Liberals who thought McKenzie too generous. They believed that the rent paid for leasehold land should reflect its true value. A later Liberal government felt obliged to alter the legislation governing Crown leases. In 1907 the lease-in-perpetuity option was abolished for someone newly taking up Crown land. In its place came a 66-year lease with an option for revaluation, recalculation of the rental, and renewal of the lease at its expiry. Some argued that the term of the lease should be even shorter. As uncertainty reigned in Liberal ranks about the rules that should govern Crown leases, pressure from leaseholders themselves to be able to freehold their land at generous valuations mounted.

After the fall of the Liberal Government in July 1912 the new Reform ministry extended the freehold option to those leaseholders who had previously been denied it. The amount of land held under the Liberals’ leases slowly declined. McKenzie’s social engineering faded as pound signs flashed before farmers’ eyes; they were understandably keen to be able to capitalise the improvements they had made, and to access the ‘unearned increment’ that population growth and the laws of supply and demand had added to the land’s value. Farmers proved much less interested in Scottish theory than in the profits to which they convinced themselves they were entitled. Social experiments have usually been defeated by self-interest.

Between 1893 and 1896 the Liberal Government became involved in banking matters. It was not for any theoretical reason, but because without State intervention the major North Island bank, the Bank of New Zealand, would probably have collapsed. In similar vein, the Bank of New Zealand’s takeover of the South Island’s Colonial Bank in 1895 was to stave off calamity. Public confidence in banks began to slide in the state of Victoria in 1891. The unease spread to New Zealand. Trading bank depositors started transferring their money to the state-guaranteed Post Office Savings Bank during the early months of 1893. On 1 September there was a run on the Auckland Savings Bank. Other banks offered ‘assistance’ to the ASB, and Seddon also promised unspecified aid.65 Confidence quickly returned. However, in June 1894 a more serious crisis developed within the Bank of New Zealand. Since the late 1880s the bank had been endeavouring to restructure because of bad debts stemming from years of injudicious land speculation.66 But the bank’s share price continued to slide, and on 25 June 1894 its directors approached Seddon and Ward for help. On the afternoon of 29 June the Premier saw the Governor, Lord Glasgow, and told him that unless the bank received immediate assistance it would have to close its doors.67 Three bills were rushed through Parliament that evening before the anxious eyes of merchants, bankers and other commercial men.68 In the main piece of legislation, the Bank of New Zealand Share Guarantee Act, the Government guaranteed an additional issue of shares to the amount of £2 million. It also appointed a president of the bank with veto powers, as well as an auditor.

These moves saved the bank, and won considerable applause for Ward, now Colonial Treasurer. Ironically, when the Colonial Bank began to collapse the following year and the restructured Bank of New Zealand was obliged to take it over, Ward became the biggest casualty of the merger. In June 1896 he had to resign from the ministry because of his heavy indebtedness to the Colonial Bank and the reluctance of the Bank of New Zealand to take up his debts. In July 1897 Ward became a bankrupt. He repaid his debts and emerged with renewed political vigour at the end of the decade to become Seddon’s principal lieutenant once more.69

While there had been a state bank of issue briefly in the 1850s and during the 1880s many farmers pushed for the creation of a state bank that would lend at lower interest rates than commercial competitors, Seddon’s banking bills were the first occasion on which the State became financially involved in a private bank.70 It was a precedent that was referred to in 1933, when the Reserve Bank of New Zealand was established in the depths of the Great Depression and was quoted again in 1945, when the Bank of New Zealand was fully nationalised by Peter Fraser’s Labour Government.

The developing relationship between farmers and the State moved closer after the election of November 1893. A friendship grew between McKenzie and Ward as the latter struggled to procure funds to help settlers on to the land. As Neil Quigley has shown, by then the Liberals’ taxation and land policies had produced an unintended result. Investors began withdrawing from farm lending after 1891.71 This pushed private interest rates upwards. In 1893 Ward briefly considered counteracting this movement by establishing a state bank to undercut the trading banks’ rates of interest. After a resounding election victory followed by the banking difficulties of 1894 he decided instead that the State should take direct control of McKenzie’s settlement programme. He decided to borrow abroad, then on-lend to farmers at a cheaper rate than was being offered by the private sector. High interest rates had made Ward’s own financial position tottery and his interests, and those of the rural community as a whole, looked as though they would be more quickly served by an infusion of money to farming through a state department.

Ward’s Advances to Settlers Act of October 1894 was posited on the assumption that the Government could borrow on the London market at 3.5 per cent and on-lend to farmers at no more than 4.5 per cent, at a time when the trading banks were charging between 6 and 8 per cent. In the event, Ward excelled himself. In 1895 he borrowed £1.5 million at 3 per cent, and was given a hero’s welcome on his return to New Zealand.72 An Advances to Settlers Office was established, and with McKenzie’s encouragement loans were extended not only against the freehold, but leasehold properties as well. Peter Coleman observes: ‘Cheap money was no guarantee that the Liberals’ small farmers would turn a profit, but it gave them the kind of fighting chance settlers had never previously had.’73

In the Liberals’ later years, the same principles lay behind their decision to on-lend money for urban housing under a branch called the Advances to Workers. Local authorities were brought into the system too, using their state loans for public works. In time the department became known as the State Advances Corporation. By March 1913, nearly £17 million had been lent to 48,000 farmers and workers.74 These credit subsidies had their desired effect, and for a time the trading banks experienced stiff competition from the State. They were obliged to keep their interest rates as low as possible. While Ward denied that he was establishing any kind of state bank, conservative critics warned that the Government was ‘marching towards a condition of State Socialism’.75

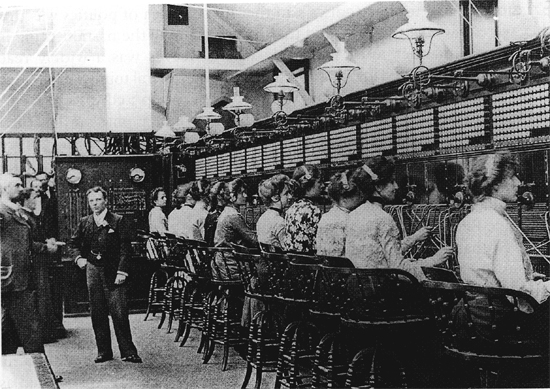

Telephones and telegrams were labour-intensive, as this 1903 photograph at the Auckland telegraph office demonstrates. Operators knew all the gossip. AIM

With so much effort being directed towards the countryside, buoyant conditions returned quickly as soon as commodity prices rose in the middle of the 1890s. But ministers also wished to assist wage workers who were a growing part of the Government’s electoral coalition. Speaking in support of the Wages Protection Bill in 1898, Ward summarised the Government’s attitude to workers with the words:

Almost every class in this country – the commercial class to a very large extent – is protected by legislation; the shipowners, the merchants, the landowners, the professional classes, all classes, in fact, are more or less protected by legislation and I say, therefore, it is very desirable to have the wage earners protected, and by so doing give effect to that which is the desire of the majority of the people of this colony.76

The Bill designed to protect workers’ wage packets from arbitrary deductions by employers was about ‘fairness’. Other ministers such as William Pember Reeves, who was Minister of Labour from 1892 until 1896, also used the word ‘fair’ a great deal. A small man with a quick, occasionally acid tongue (critics said that his sole idea of politics was that they were ‘a war of tongues, and that he who can say the nastiest thing in the nastiest manner must inevitably win’), Reeves was a widely read journalist who dabbled in poetry.77 Alone among Liberal ministers he often liked to use the language of class warfare. He was opposed to ‘squatters’, ‘runholders’, banks and ‘monopolists’ and could paint graphic word pictures about their ‘inequitable’ behaviour. Reeves went further. As he nestled into his reformer’s role he sought to cast a nationalist cloak over his legislation, calling it an expression of New Zealand’s growing sense of national identity. On this point he was right.

While Reeves could be aggressive, he could be equally conciliatory. He believed that the struggle between capital and labour evidenced in strikes such as the great maritime upheaval of 1890 was unnecessary; it could be calmed by conciliation and arbitration of the points at issue.78 In 1892, when commenting on an early draft that he was circulating of his proposed Conciliation and Arbitration Bill, Reeves wrote: ‘it is not a bill which attempt[s] to give an advantage to any one class: it [is] designed to fairly hold the scale between employer and the employed and [is] prompted as much in the interests of one class as the other’.79 Underlying other legislation was his belief that organised labour, which had been badly beaten in 1890, should be helped to the point where unions could become equal partners at the negotiating table with employers. Reeves was nothing if not idealistic; his legislation was another early example of social engineering.80

One of Reeves’s first moves on taking office was to establish a Labour Bureau to assist the unemployed find work. Information was distributed and workers were given free railway passes to travel to areas where there were vacancies. In 1892 the bureau, headed by a fellow idealist, Edward Tregear, became the Department of Labour. Over the next decade the department assisted more than 90,000 men and their dependents find a family income. Some were put on to a brief experiment in state farms near Levin.81 For others in employment there was a series of acts including the Truck Act which obliged employers to pay their workers in money rather than kind. Two Factory Acts followed. The first, in 1891, gave legal definition to a factory, the second, in 1894, required registration and inspection of factories, specified maximum hours of work for women and young persons, and prevented those under fourteen being employed in factories. A Shop-assistants Act in 1892 also dealt with sanitation and inspection, and instituted a requirement for half holidays. By 1896 4600 factories with 32,000 workers and a further 7000 shop assistants were registered with the Department of Labour. The department employed 163 factory inspectors.82 The Shipping and Seamen’s Act 1894 specified minimum crews and other safety conditions for shipping. New Zealand’s developing State could be every bit as paternalistic as a policeman.

The Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1894 is regarded by some commentators as the legislation that did most to influence thinking about social policy and the structure of twentieth-century New Zealand society. Reeves’s biographer, Keith Sinclair, notes that without Reeves’s personal effort, particularly his constant drafting and amending of the initial proposal, ‘it is improbable that compulsory arbitration would have been introduced’. Certainly there was no widespread public demand for the legislation nor were other parliamentarians pining to see Reeves’s scheme enacted. Some years later Reeves wrote of the scene when his bill passed: ‘Mildly interested, rather amused, very doubtful, Parliament allowed [the I.C.&A. Act] to become law, and turned to more engrossing and less visionary matters’.83

The Act passed on 31 August 1894. The preamble described the new law as ‘An Act to encourage the Formation of Industrial Unions and Associations, and to facilitate the Settlement of Industrial Disputes by Conciliation and Arbitration’. It made it easy for a group of seven or more workers to form a union, to seek registration and then enter by law into industrial agreements or awards with their employer over wages and conditions for terms of up to three years.84 A breach of an agreement by either party could result in a fine. Disputes were to be brought before conciliation boards representing both parties. If the issue remained unsettled then either party could take it to the Court of Arbitration which was presided over by a Supreme Court judge. Strikes and lockouts were forbidden during this process. Between 1905 and 1908 the laws regarding strikes were tightened so that it became illegal for a union to strike while an award was in force.85

The I.C.&A. Act remained a cornerstone of New Zealand’s industrial legislation for more than 70 years. Its origins were not pure theory. Reeves had read widely on the subject of labour relations. He carefully considered an unsuccessful bill providing for voluntary arbitration that had been introduced into Parliament in 1890. But as James Holt has pointed out, it was the political environment that Reeves operated in that enabled him to succeed. In the early 1890s the Liberals were still fashioning their electoral coalition. They were determined to draw wage workers into their fold. Given this political imperative, the opposition of employers to compulsory arbitration could be swept aside. Holt comments: ‘The essence of the political situation which allowed compulsory arbitration to become law in New Zealand … was that the unions, being industrially weak, lacked the will to oppose it, while the employers, being politically weak, lacked the power to prevent it.’86

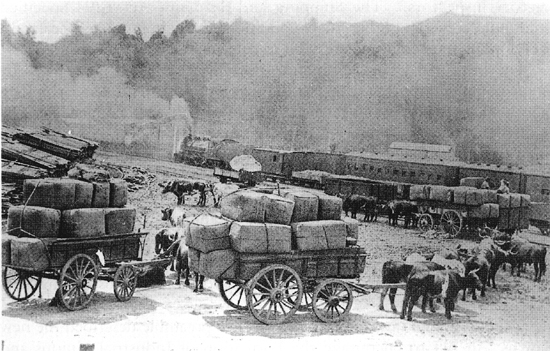

Bales of wool being loaded on to a train in the Rangitikei area, 1911. Wagener Museum

More significant to the longer-term relationship between the people and the State were developments following the passage of the I.C.&A. Act. The culture of industrial relations that developed over the next two decades owed more to decisions by the Arbitration Court on workaday problems than to any legislative provision by Reeves. An elaborate balancing act between employers and unions that had little to do with realities within the wider industrial market place took place; governments in their capacity as legislators became the ultimate enforcement agency if one side or the other – it was usually perceived to be the unions – overstepped the mark. Within this framework the tussle between unions and employers continued. Unions were quick to organise, using the seven member rule; trade union members reached nearly 67,000 by 1912. Wages rose steadily, but prices tended to move slightly faster. In a 1919 study that is still regarded as definitive, G. W. Clinkard pointed out that between 1901 and 1919 food prices rose by 63 per cent while minimum wage rates rose only 52 per cent. During the same period the average hours worked dropped from 48 per week to 46, to put them amongst the shortest in the world. As the working hours decreased there was no marked increase in productivity as envisaged by the most optimistic of the social engineers.87

Arbitration conferred more power on trade unions by increasing their bargaining capacity, and this in turn advanced the relative position of wage-earners as a class. But the changes came at a cost. Unskilled labour in New Zealand did better out of the years after the I.C.&A. Act was passed than skilled labour, with the result that there were seldom enough young men taking up apprenticeships. Moreover, as the Royal Commission on the Cost of Living in New Zealand pointed out in 1912, trends in prices and wages could not continue indefinitely without having a harmful impact on New Zealand’s trading position.88

For nearly two decades employers constantly grizzled about the I.C.&A. Act, claiming that it had disrupted ‘the natural and proper relation beween master and workman’, and that the arrangements were ‘too obviously artificial to be permanent’. In 1904 one employers’ spokesman complained that the Liberals’ labour legislation was ‘sapping our energies and clogging our enterprise’. While many continued to rail against ‘the baneful influence of ultra-Socialistic legislation’,89 most eventually came to value the Government’s stiffer anti-strike measures, and applauded their use during later industrial upheavals. In the meantime, however, the power balance had clearly tipped by 1907 in favour of unionists. Having grown under state patronage, some began to regard the law as a ‘straitjacket’ that hindered their capacity to exploit their growing strength.90 The Liberals were discovering what many others did in later years: the more governments do to help interest groups, the more those groups expect.

Of particular significance was the argument that went back and forth between unions, the court and employers over whether a company’s profits were a relevant factor for the court to consider when arbitrating on wages. For many years the court knocked back such suggestions. As James Holt observes, there was also much discussion about whether a ‘fair’ standard of wages could be fixed, something envisaged by Alfred Deakin’s Australian Liberals and by the Australian President of the Arbitration Court, Mr Justice Higgins. Important too was whether a minimum wage in some industries should apply for all parts of the country. In later years these issues widened as the concept of a national ‘living wage’ emerged; unions pushed for, then achieved, national contracts.91

In the 1890s New Zealand began to embark on a social concept of remuneration that in time divorced wages from many international marketplace realities. Sheltering behind protective tariff barriers, and operating within an increasingly regulated labour market, New Zealand wage workers, like public servants, eventually came to enjoy remuneration that was high by world standards. The country was well on the way to becoming what Michael Joseph Savage later called an ‘insulated economy’. In 1905 the benefits of such an economy were becoming apparent to many. Sir Joseph Ward declared on the stump during that year’s election campaign that at £381 per annum, New Zealanders had the highest average per capita income in the world. His assertion, as Margaret Gait has shown, was probably correct.92 Seddon had recently called New Zealand ‘God’s Own Country’. A supreme confidence in the paternalistic power of the State to bring about ‘fairness’ and social harmony seemed not out of place.

The philosophers: ‘Jock’ McKenzie, with his ideas on land reform; and William Pember Reeves, the experimental socialist. ATL F-1054161/2; F-31783-1/2

Not surprisingly, New Zealand’s emerging welfare state enjoyed considerable public support. By any standards it seemed to be working. And a sense of national pride developed as overseas social reformers visited, often departing with a missionary zeal to introduce ‘the New Zealand Way’ to their own countries.