On 6 December 1905 Richard John Seddon enjoyed his last and biggest victory at the polls. He now commanded 60 MHRs in a Parliament of 80 members. Most urban workers, many small farmers (particularly those in remote areas), public servants and a considerable number of employers subscribed to the Liberals’ interventionist vision.1 ‘God’s Own Country’ attracted visitors with an interest in politics and theory. After studying antipodean reforms, André Me tin argued that there seemed to be no predetermined pattern to state intervention and that Australia and New Zealand were simply practising ‘socialism without doctrines’.2 Increasingly, however, foreign observers thought that the Liberal Government was going further and pioneering a new world order where ‘the spirit of brotherhood’ would ‘supplant… the spirit of individualism’. Frank Parsons, a reformer from Boston, wrote in 1904 that he believed New Zealand was ‘the birthplace of the 20th Century’.

For several decades to come, American, British and French commentators came, looked and wrote about New Zealand’s state activity. Many argued that the antipodean approach to government ought to be emulated elsewhere. The English Fabian Society was developing an enthusiasm for the collectivist State. It argued that philosophers, engineers and scientists working through agencies of government could produce answers to social problems. Beatrice and Sidney Webb visited New Zealand in 1898. Although they found Seddon ‘abominably vulgar’, they were impressed with his Government’s work. Beatrice concluded her diary with the words: ‘Taken all in all if I had to bring up a family outside of Great Britain I would choose New Zealand’. Sidney noted there was less individualism in New Zealand and liked Seddon’s quest for ‘social and economic equality’.3 Some visitors saw religious significance in the Liberals’ reforms; the American journalist, Henry Demarest Lloyd pronounced New Zealand ‘the most truly Christian country of the earth’.4 Andre Siegfried admired many of the State’s interventions when he wrote about New Zealand in 1904. However, he was less inclined to think them exportable, arguing that the reforms were unique to New Zealand, a combination, as David Hamer has noted, ‘of time, place and heredity’.5

In Australia and New Zealand there was a steady flow of literature from abroad that encouraged the emerging colonial intelligentsia to discuss ideas. Some American books glorified the State as an engine of progress. Henry George’s earlier writing reached New Zealand, especially his Progress and Poverty (1879). It promoted a ‘single tax’ on land exclusive of improvements. The American Edward Bellamy’s Utopian romance, Looking Backward (1888), sold 200,000 copies around the world in less than two years. Situated in the year 2000AD, it told of a paternalistic state, something akin to heaven, that ensured employment for everyone, allowed people to retire at 45, ensured independence for women, cooked meals in public kitchens, maintained public laundries and educated everyone.6 Herbert Croly’s writing, particularly The Promise of American Life (1909), argued that in an ideal society the public, not the private sector, must dominate; the State, rather than the individual, ‘would define the common good, and see to its fulfillment’.7

It would be an exaggeration to suggest that there was a substantial intellectual climate developing in New Zealand that favoured state intervention. While there were influential university teachers, such as the free spirits Alexander Bickerton and John Macmillan Brown at Canterbury University College, and younger men like J. G. Findlay and H. D. Bedford at Otago University, there were no homegrown philosophers of the standing of the Americans Croly or John Dewey to inspire a generation of reformers. Nor had there been a William Graham Sumner or a Samuel Smiles preaching the conservative gospel of self-help for people to react against, although, as Miles Fairburn has shown, Smilesian values had some following in New Zealand.8 However, there was a growing confidence in governments as agents of progress. This was backed by books imported from abroad. John Stuart Mill was quoted in Parliament during the debates on charitable aid in 1877. In 1881 Atkinson bought eight books by American political economists; they were mainly publications from Harvard University Press. Ballance read Henry George and J. S. Mill; Pember Reeves developed a detestation of the English land system from reading Williams on Real Property; while Edward Tregear seems to have been steeped in the works of George, Mill and Bellamy.9 In 1883 a Land Nationalisation Society was established in Dunedin and according to Timothy McIvor freethought associations were formed that year in several parts of New Zealand. Ballance and Sir Robert Stout took an interest in their activities.10

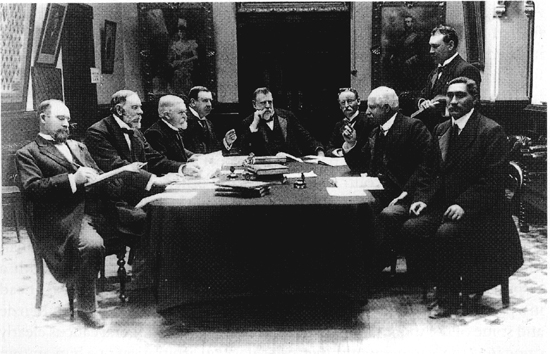

Prime Minister Seddon presides over one of his last Cabinets early in 1906. To his immediate left is William Hall Jones, who briefly succeeded him, while Sir Joseph Ward (immediately to Seddon’s right) was overseas. ATL F-20806-1/2

Some of the discussion groups set up in the Antipodes took an interest in Britain’s middle-class Fabian Society established in 1883.11 In Australia there were reformers who glorified Alfred Deakin’s tariff policies that he dubbed ‘the New Protectionism’. They raised wages and protected them with a high tariff. Dr Harold Jensen’s The Rising Tide: An Exposition of Australian Socialism (1909) was widely read. It defined socialism as ‘science applied to life’. Like Bellamy, Jensen hoped for a Utopian future where no one would need to work more than four hours a day. Deakin and Ward knew each other well.12 New Zealand’s best known reformers were Reeves and Tregear. They shared George Bernard Shaw’s belief that ‘science’ - a word first used in the New Zealand social context by Wakefield – could be applied to society, and that it was possible to ‘cultivate perfection of individual character’ by ‘scientific class warfare’.13

Where state help was required, however, no one thought people should be paid for doing nothing. Tregear, in particular, had no time for malingerers.14 This strain ran through the Fabian discussion groups of the 1890s and was an underlying tenet of the Fabian Club that was established in Auckland in 1928. Long before then, however, a distinctive working-class culture to the left of the Liberal Party had taken root in New Zealand. Arguing for an avowedly collectivist solution to workers’ needs, it was fuelled by radical doctrines from Europe, often via Australia. However, in its heyday this new movement, too, laid stress on work, as well as the need for it to be justly rewarded.

It is hard to detect any very consistent ideology underlying New Zealand’s Liberal reformers except an implicit faith in the ‘goodness’ of state action. Some of their eagerness to use the State stemmed from their belief that settlers who had been led to expect assistance in their quest for survival had a right to contract fulfilment. On other occasions the Liberals’ actions were motivated more by a desire – as Gary Hawke puts it - ‘to balance competing interests within New Zealand’, to ‘moderate conflict within society, as well as protect it from outsiders’. Ward, in particular, often described the State as an arbiter between interest groups, with a responsibility to help everyone.15 A small minority wanted to press ahead in a paternalistic manner, using the State to develop a new society. McKenzie and some of the more enthusiastic leaseholders in the Liberal caucus clearly came into this category, and Reeves’s views on arbitration put him among the more paternal social engineers of his day. This last group, which was sometimes labelled the ‘progressives’ or derided in later years as ‘faddists’, was distinctly middle class. They read widely and were more attuned to European and American thinking. For these people it was not enough to push ahead in a piecemeal, pragmatic manner helping people to ‘get ahead’. Their eyes were on the future shape of society, one where, unless action was taken, land would all have been alienated into private hands, and European class war would become the dominant feature of life. During Ward’s leadership of the party after 1906 the ‘progressives’ were a constant irritant. The Liberal MP, T. E. Taylor, and many of his fellow temperance workers, wanted the State to banish the trade in alcohol. Two MPs, A. W. Hogg and George Fowlds, had other ideas and struck off into uncharted territory, in Fowlds’s case behind a banner labelled the ‘New Evangel’. At their extreme the ‘progressives’ had more in common with the developing Labour political groupings whose dirigiste attitudes to the economy frightened the elderly, and many middle-class people.16

Echoing the comments of André Métin in 1901 and Pember Reeves the following year, Keith Sinclair observed that the Liberals on the whole possessed doctrines, but were not doctrinaires. They were experimental, not theoretical – a point made by Siegfried in 1904. In his unpublished memoirs Reeves denied any suggestion that he was ‘an original thinker’ and suggested that he, like his contemporaries, got his ideas on labour relations from English, American, German and Australian sources:

The air was thick with schemes and suggestions; there were even suggestions in New Zealand. What one had to do was to form a view of what was wanted and desirable in New Zealand. Then one looked round to see whether there were any schemes or suggestions that would be useful. From these you selected what seemed likely to be of service, taking one, rejecting many. What you took you pieced together, modified and endeavoured to improve upon. The result was something added to a bill, sometimes one clause, sometimes several. The work was interesting but extremely laborious. The amount of adapting, revising, adding and taking away was very great; over and over again one changed one’s mind.17

This was the statement of a pragmatist, not an ideologue. J. C. Beaglehole observed many years later: ‘of few ministers can it be said that they have brooded over any coherent body of principle’. Métin’s quip about ‘socialism without doctrines’ applied to most Liberal parliamentarians. His view has been taken up by one of New Zealand’s recent political theoreticians, Simon Upton, when comparing earlier politicians with those who were engaged in downsizing the State after 1984.18

Nor was there much sign that doctrine drove New Zealand’s conservative thinkers at the time. In Upton’s view, political conservatives in New Zealand, more than in older societies, were ‘conservatives of interest’ rather than ‘conservatives of instinct’. Without any adherence to any conservative philosophy they simply went along with policies they deemed good for ‘men of property’.19 While they were usually more cautious, their principles were no less flexible than their Liberal counterparts’. As Jim McAloon has shown, they were easily led if their best interests were served by change. Atkinson’s scheme for national insurance appealed to some, but by no means all conservatives; while it might be authoritarian, it obliged people to save for themselves. Another so-called conservative, William Rolleston, who was briefly Leader of the Opposition during the early years of Liberal hegemony, has been described by his biographer as ‘a keen social reformer’. Francis Dillon Bell, who came to be regarded in the 1920s as the archetypal conservative of his generation, was a vigorous proponent of municipal works, libraries, bath houses, abattoirs and waterworks while Mayor of Wellington in the 1890s. He could complain about the ‘dictatorship’ of the Liberals but then support most of Reeves’s labour bills in the House of Representatives between 1893 and 1896, believing them to be as helpful to employers as they were to unions. In middle life he keenly embraced the temperance movement, believing, paternalistically, that it would be good for the working classes, even though he was known, himself, to like whisky. McAloon points out that the Liberal Government’s opponents seldom presented a consistently conservative alternative; the wealthy, he says, often simply ‘kept their heads down in face of the [Liberals’] populist onslaught’.20 More often than not the political divide in New Zealand has been between the winners and losers from a particular piece of state action, rather than over any disagreement on the principle of whether the State should have been involved in the first place.

Some historians have argued that the reformist zeal of the Liberals departed when Reeves left for London in 1896 to assume the High Commissionership.21 In fact, the Liberal Government still had ahead of it sixteen years of energetic, pragmatic intervention. Some energy was spent on social policy. By the turn of the century the age and sex profiles of New Zealanders were becoming those of a mature society. The census of 1901 showed that women, who had been no more than 60 per cent of the male population in 1861, now nearly equalled them in numbers. Moreover, by this time there were many older people, a disproportionate number of them men. Most of the original settlers were nearing the end of their lives; a great many from the gold rush and Vogel years needed to retire. By the 1890s old age and poverty were more serious problems than when Atkinson had considered them a decade earlier. While many old people had families to rely on, lots of men had never married because of the shortage of women in early colonial society. A downside of the Arbitration Act’s award wages was that some factories could no longer afford to employ old workers on a retainer basis. While the State had become involved in various social activities because there were so few charities in the new country, its busy experimentation sometimes deterred individual acts of charity.

By this time the earlier opportunity to provide a system of national insurance similar to Atkinson’s proposal had been lost. During the worst years of the depression at the end of the 1880s the need to increase taxation to fund a compulsory contributory scheme deterred politicians from revisiting the issue. Nor did friendly societies enjoy a boom. In 1893 they had fewer than 30,000 members. While many workers had life insurance, the policies were for relatively small sums which, if cashed up, would not provide annuities.22 In June 1894 when a parliamentary committee was established to consider making provision for the elderly, old age and poverty were catching up with New Zealand. Even if a decision had been made in the mid-1890s to revive Atkinson’s proposals for future generations, there was an immediate problem that required a solution.23

In the event, because the economy was picking up and the Government’s revenue was now rising steadily, the ministry decided to take the easy way out, despite some opposition within the Liberal caucus. The Government pushed aside arguments for a contributory system and introduced a taxation-based scheme. In July 1896, when Seddon introduced his first Old-age Pension Bill, an election was due in the spring and it was no time to raise taxes. The bill lapsed, was much discussed during the campaign, then introduced again in 1897. It passed the House but was defeated in the Legislative Council. In 1898 a new Old-age Pensions Bill was finally enacted. It was said to be the first such enactment in the British Empire. One leading backbencher summed up what many thought: ‘it is the duty of the State to make proper provision for the aged’. The Act provided for a payment from the Consolidated Fund of a pension of £18 per annum to someone of 65 or more. The pension was increased to £26 in 1905 in time for another election. Asiatics and unnaturalised immigrants were not covered, and in 1901 Maori rights to the pension were reduced because, it was argued, too many recipients were handing their pensions over to their younger kin.24

Applicants for the pension were required to be of’good moral character’ and to be leading ‘sober and reputable’ lives. Applications had to be made in person before a magistrate and were not entertained from people who had been convicted of serious crimes during the preceding twelve years. Some said that a man had to be a saint to earn a pension in New Zealand. A means test cut the pension for anyone with an annual total income, including the pension, that exceeded £52 per annum. This was changed a few years later to £78 for a married couple and was to be altered again many times over the next 78 years. David Thomson has described the early payouts as ‘decidedly mean by comparison with those enacted elsewhere around the turn of the century’. That deterred few from collecting; by 1912 a total of 16,649 people were receiving old-age pensions.25

In October 1911, on the eve of another election, a Widows’ Pensions Act was passed by Sir Joseph Ward’s Liberal Government. The Act consolidated the law relating to old-age and military pensions at the same time. The term ‘widow’ was defined sufficiently widely to include a woman whose husband was in what was then called a ‘mental hospital’. However, payment of a pension was made only where there were children. Ward estimated there were 3000 likely beneficiaries.26 A widow with one child under fourteen received £12 per annum, with a further £6 paid for each subsequent child. Again there was a means test. In the same year a Military Pensions Act was passed, although in 1912 payments were confined to veterans of the wars of the 1860s. In 1911 miners suffering from pneumoconiosis also began receiving payments from a small relief fund set up by the Government the previous year. Electoral considerations seem to have been the principal driving force behind the State’s complex maze of state-funded, rather than contributory, pensions. So long as the Crown’s income was rising steadily as a result of the buoyant economy, ministers felt emboldened to embark on spending programmes for those who had difficulty helping themselves.

Side by side with pensions paid from the Consolidated Fund, the Liberals also tried to encourage self-help among those who were fit and able. There were income tax exemptions for life insurance premiums. Friendly societies, which were increasing in number and reached 609 by 1910 with a combined membership of 68,000, were referred to by the Prime Minister as ‘well-organised and deserving bodies’. Ward hoped that voluntary efforts to insure against sickness and bad health would mean there was no need to introduce the British system (or Atkinson’s) of compulsory insurance. The Government hoped that friendly societies would expand their array of benefits to include unemployment, although Ward stopped short of legislation requiring them to do so.27

Prime Minister Ward took comfort from the rising numbers paying into Public Service Superannuation. In 1911 his government expanded the superannuation principle to the wider public. The National Provident Fund was sometimes referred to as a ‘Government friendly society’. In return for contributions into the fund, any private citizens between the ages of 16 and 45 could have their accounts topped up by a state contribution. The scheme provided maternity medical expenses, sickness and death benefits, as well as a weekly pension at 60 which varied according to the level of contributions.28 Despite the fact that its fund was guaranteed by the Government and its benefits were more generous than those offered by the average friendly society, the National Provident Fund enjoyed limited success. Only 29,441 members belonged to it in 1926.29The bulk of New Zealanders were demonstrating that they were not particularly provident, believing by this time that the State, in times of need, would probably provide at least minimal support.

The public’s growing confidence in the State was not misplaced. When Ward became Minister of Public Health in November 1900 he appointed an energetic Scotsman, Dr James Mason, as his Chief Health Officer. Mason was a trained bacteriologist. Using the Public Health Act 1900 he oversaw a campaign among local authorities to improve sanitary standards and introduce cleaner drinking water.30 Vaccination against several diseases was also promoted, but as late as 1912 only 5 per cent of children were being inoculated against smallpox. In that year the Liberal Government, a few weeks before it lost office, decided to initiate a system of medical inspections of children before they passed out of primary school.31 In later years routine vaccinations of children against measles and whooping cough were administered by school doctors at no direct expense to the parents.

Early dentistry in the Ureweras in the 1890s; Maori getting their own hack? NZH

The last year of the Liberals’ regime saw other significant health moves. The Pharmacy Board was working on a set of regulations governing the labelling of food and drugs, and the protection of meat and milk products. They were gazetted in March 1913 under the Sale of Food and Drugs Act 1907. In addition, Maori medical services, which had previously been provided in a haphazard way by several government departments, were coordinated under the aegis of the Department of Public Health. A rudimentary district nursing system was established in areas where Maori were numerous. The Inspector-General of Hospitals made it clear that the same principle underlining the provision of hospital services to Pakeha should apply to Maori. ‘There is nothing in Act or treaty to show that the country is under any obligation to render free medical assistance to the well-to-do Native; but for the indigent Native there is no doubt as to our obligations, and it is to be hoped that Hospital Boards, who sometimes resent the admission of these patients to their hospitals, will bear this in mind.’32

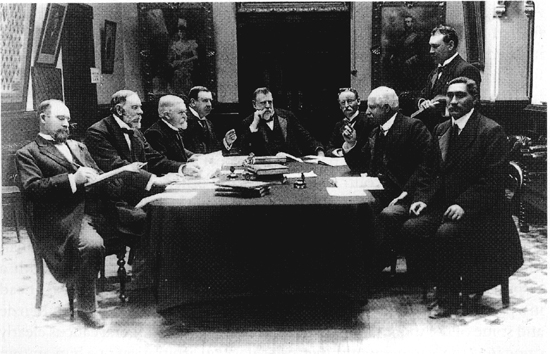

Early ambulance services; on the way to Rawene Hospital in the north, about 1900. ATL F-34914-1/2

There is little doubt that plummeting infant mortality figures in the first decade of the twentieth century owed much to all this government activity on many fronts. Subsidies on a pound for pound basis were made available to local authorities for sanitation and water purification. In the Auckland region, Devonport was held to be the model local authority. It completed its drainage scheme in 1902 and cases of enteritis soon vanished from the borough’s schools. Following an impassioned plea from dentists to the Government in 1905, steps were also taken to teach oral hygiene in schools.33

Contributing to infants’ survival rates was the construction of St Helen’s state maternity hospitals. They were provided for in the Midwives Act of 1904. Between June 1905 and April 1907 St Helen’s hospitals opened their doors in all four main centres.34 While they catered for women whose husbands earned less than £4 per week, they were not charitable institutions. They charged fees, although these were kept low by state subsidies. St Helen’s hospitals also provided training experience for women who eventually became state-registered midwives. An increasing number of women chose to use the hospitals, availing themselves of the midwives’ skills. As Charlotte Parkes has observed, the hospitals ‘became institutions in New Zealand’s tradition of liberal reform, providing a high standard of professional care for working-class women and setting the standard for midwifery practice throughout the country’. However, Philippa Mein Smith shows that by 1920 approximately 65 per cent of all births still occurred in homes.35

Despite intervention on so many fronts, the Liberal Government’s health policies did not extend to subsidising visits to general practitioners. To have done so would have cut across the self-help message that ministers were trying to pass to people to join friendly societies. But some Liberal politicians were worried. Walter Carncross of Dunedin, an old friend of Ward’s, who served almost continuously in the House and the Legislative Council between 1890 and 1940, commented in 1893:

I know this is a big question, and that it is socialism to suggest that the Government should take part in a matter of this kind. But I believe it is one of the things which the Government will yet have to face. I know personally of poor people who have died for fear of incurring debt by calling in a medical man. I have known people who had children lying on what turned out to be their death beds; they put off until the last moment the calling in of a medical practitioner because they feared the bill they would have to pay afterward and those people have died. I believe … that attendance on poor people will yet become one of the offices of the State.36

Carncross lived long enough to assist in the passage of the Social Security Act in 1938, but died before the system of subsidies for visits to general practitioners went into effect.

The Liberal Government also expanded education at a fast rate. Many new schools were built each year, and the number of teachers in public primary schools grew more rapidly than students, enabling class sizes to be reduced.37 By 1910 most teachers were fully certificated. In 1912 nearly 10,000 students went on to secondary schools. The number of’free places’ at these schools rose by 180 per cent in the period 1903-12 and by the end of the Liberals’ term in office fewer than 20 per cent of all secondary students paid any fees.38 Technical education expanded too, and in 1912, 13,500 students were attending classes at eight institutions around the country. Each technical school received a pound-for-pound subsidy on fees collected. Evening classes became more popular each year. By now more Maori children were attending public schools than native schools, indicating their increasing fluency in English. It was estimated that in 1911 almost 84 per cent of the entire New Zealand population could read and write, which was a high percentage by world standards of the time.39

A host of related benefits accompanied public education. After 1895 children could receive assistance with rail transport to and from schools, and over the next few years small boarding allowances were paid as well. Industrial schools that were really reformatories also received government subsidies,40 as did schools for the blind and deaf. The Government paid for a school for intellectually handicapped children in North Otago. School libraries received pound for pound subsidies on funds collected locally, and the sum of £3,000 was set aside annually in the budget for the purchase of new public library books. Four university campuses were in operation by 1912. They taught 2114 students, a number that had risen rapidly in recent years. Since 1869 when a campus first opened in Dunedin, New Zealand’s universities had produced a total of 1661 graduates.41 Each year, as the economy improved, the governments of Seddon and Ward spent more and more on education, trimming the sums required of parents and their communities. The Government was well on the way to providing what later generations called ‘free’ education.

For the first time the Government became involved directly in permanent housing for families. As cities grew, jobs in manufacturing and servicing increased. The Liberal Party cultivated the growing urban work force, eager to ensure that workers saw the Liberal Party as their electoral vehicle, rather than the various labour political groups that were beginning to compete for their affections, and which had elected David McLaren as the first independent Labour MP in 1908. 42 This threat from the left led Seddon to promise during the 1905 election campaign that he would extend the Advances to Settlers scheme to loans for workers’ housing. On 29 October 1906, nearly five months after Seddon had died on board ship while returning from an Australian trip, the Government Advances to Workers Act passed through Parliament. Applications for housing loans at an interest rate of 4.5 per cent were considered from January 1907. Loans were available to manual or clerical workers whose income did not exceed £200 pa, and whose sole land holding was the allotment on which it was proposed to erect a dwelling. Advances from the Government were secured by a mortgage over the whole property. By 1913 nearly 9,000 loans had been extended by the Government.43 A government body that eventually became the State Advances Corporation, then the Housing Corporation of New Zealand, was beginning to take shape.

With the Workers’ Dwelling Act 1905, the Government began to build rental accommodation for those whose incomes did not exceed £156 pa. Seddon’s inspiration seems to have come from a visit to rental housing areas in London and Glasgow at the time of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. Tregear, as Secretary for Labour, convinced the Prime Minister in 1904 that rental houses had the virtue of replacing private landlords with the more benevolent State, a move that could help cap the rising cost of living. When built, the houses were let for a fixed period at 5 per cent of the capital cost, plus insurance and rates, with a right of renewal after 50 years.44 Seddon envisaged building 5000 workers’ cottages. In the event only 646 were built, in Ellerslie, Otahuhu, Petone, Coromandel, Seddon Terrace (Wellington), Sydenham and Windle (Dunedin). Sir Joseph Ward, who became Liberal Prime Minister in August 1906, visited the first completed Worker’s Dwelling at 25 Patrick Street, Petone, soon after taking office.

Efforts were made to ‘talk up’ Workers’ Dwellings. But the concept never took off; many of the houses were two-storeyed and regarded as ‘too swell’. Their rents were always too high for many low-paid workers, and most were not close enough to railway stations. Ward’s decision to alter the rules in 1910 and to allow the houses to be purchased by their inhabitants failed to make the scheme more attractive, and few were sold.

After the influenza epidemic at the end of 1918 much official concern was expressed about substandard inner-city housing. A Housing Branch of the Labour Department was established, and in 1923 it became an integral part of the State Advances Office. However, the Reform Government placed its emphasis on home ownership rather than rental housing, with the result that poorest paid workers found housing a problem until the late 1930s when the Labour Government embarked on a huge state rental house building programme. While designed with flair, these dwellings were smaller; their subsidised rentals made them cheaper, too, than Seddon’s workers’ dwellings.45

Motives for the Liberals’ state experiments varied. Electoral considerations and humanitarian concerns coincided occasionally with a belief that government money could be saved if the State involved itself in some activity. In 1901 the Government passed the Coal Mines Act, which established state mines in direct competition with privately owned mines. Coal was the major source of energy at the turn of the century. Ministers were worried about its rising cost for railways and heating government offices. A Royal Commission was established in 1900 to look at aspects of the coal industry. The commission’s report in May 1901 suggested that if the State bought a Westport mine, retailed coal from it and established a ‘fair price’, then coal prices overall would probably fall.46 Since the Government’s agencies were consuming 12.5 per cent of all coal produced in the country, the idea of the State running a mine or mines had attractions. A Manager of State Mines, A. B. Lindop, was appointed. At the end of 1902 100 miners were engaged to work a mine at Rununga. Within eighteen months coal was being marketed from it. The numbers of employees rose to nearly 400 by 1912. By this time the Government had invested £254,947 in State Mines.47 There was a bonus inasmuch as any surplus coal could be sold through state depots in cities, thus ensuring competitive prices for urban consumers. Ministers adamantly denied any intention of engaging in ‘ruinous competition’ with the private sector, asserting that their object was simply to maintain a ‘fair and reasonable average’ price. Both the taxpayer and the consumer, so it was argued, would benefit from such state commercial activity.48 It was an early example of government efforts to create a competitive market where it suspected that private producers were in collusion.

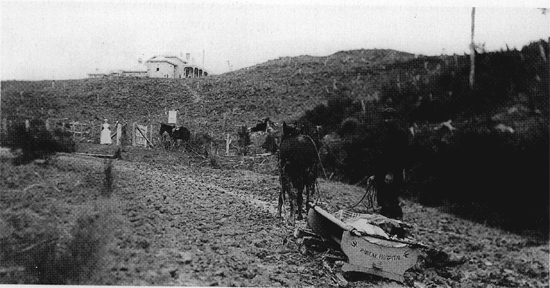

Christchurch’s State Coal Depot, 1905. Canterbury Museum

The demand for coal increased rapidly; between 1909 and 1912 it was necessary to import extra supplies. The shortages meant that the retail cost was higher in 1909 than when State Mines was initially set up. Prices continued to rise and in 1916 became the subject of a Board of Trade inquiry. Whether the experiment in state mining and supply kept prices below what they otherwise would have been, as ministers constantly argued, cannot be established with certainty. The State issued loan debentures to facilitate expansion. According to official figures State Mines was returning 5.28 per cent on gross capital expenditure in 1917. The mines, however, were always greedy for further investment. In 1913 a revaluation of the assets resulted in £45,000 having to be written off. Furthermore, State Mines was prone to industrial stoppages. Miners were beginning to realise that threats of political action would be taken seriously.49

By the middle of the 1920s State Mines was chronically short of working capital. It was unable to operate like an ordinary commercial concern. Treasury provided new investment money and was responsible for the interest and redemption of State Mines’ debts. It creamed off any surpluses as it saw fit. On 31 March 1924 State Mines had liabilities totalling nearly £382,000 and assets worth £194,000. The operating account showed a net profit after paying interest of £15,742. In a time of high unemployment during the Great Depression a small level of profitability saved State Mines from the close scrutiny given to other government departments. By 1938 the two State Mines employed the same number of miners as in 1912. However, the total amount of coal being produced was 36 per cent below 1912. Profits had slumped badly and there was no longer any significant return shown on the State’s investment in the mines.50 Introduced initially to save money, State Mines were well on the way to becoming a dead weight on the exchequer.

Seddon’s Cabinet extended Vogel’s insurance scheme of 1869 in the belief that the public could benefit from lower insurance charges if the Government entered the marketplace. Following amendments to the Employers’ Liability Act in the early 1890s many employers sought insurance coverage at a more competitive rate than was provided by private companies. Ward first advanced the idea of a state insurance scheme in 1896. In the New Zealand Accident Insurance Act 1899 the Commissioner of Life Insurance was given powers to insure people against accidents; he could also insure employers from liability for accidents to any of their employees.51 At the same time other pressure groups were pushing for cheaper fire insurance coverage than was on offer from private companies. Eventually, after several trial bills, an act was passed in 1903 setting up a State Fire Insurance Office. A board consisting of the general manager, the Colonial Treasurer, the Government Insurance Commissioner and two other government appointees was appointed. Early in 1905 the office opened its doors for business.

State Fire’s initial premiums were 10 per cent less than those charged by private companies. Agents drumming up business were specifically advised to inform customers that State Fire ‘is a Government institution and consequently the insured are guaranteed by the State’.52 When the private companies immediately retaliated and endeavoured to drive State Fire out of business by refusing to accept any reinsurance from it, Seddon labelled their conduct ‘monstrous and immoral’. While in London in 1902 he had ascertained that it would be possible to get reinsurance abroad and through the Agent General in London he now negotiated with Lloyds of London. The private companies eventually learned to live with their state competitor. Despite the fact that State Fire enjoyed the advantage of not paying income tax until 1916, its early years were not easy. There were several when the office made a loss. Conservative ideologues were angered by the State’s entry into a market where private enterprise was already well established. The idea that the Government was using public money to compete against private enterprise riled a later Minister of Finance, Downie Stewart, who wrote in 1910: ‘The State ought not to sell services or goods to one portion of the community at less than the cost price and make up the deficit by taxes upon the whole community.’53

Until 1990, when Norwich Union purchased it, State Insurance, as it eventually became known, continued to trade as a government-owned organisation. It provided a wide range of insurance at competitive prices to clients who tended to be more numerous among middle and lower income groups. Alan Henderson, the historian of the Insurance Council, believes that State Fire’s presence in the market place did keep other premiums lower than they might otherwise have been. Of particular note is the fact that State Fire was one of the first to introduce no-claims rebates. With all its backing it is not surprising that by 1920 State Fire carried a greater value of fire risks than any other company in New Zealand. Liberal, conservative and Labour governments retained it in public hands, all believing State Fire’s position in the marketplace ensured genuine competition. Of particular significance is the fact that State Insurance traded profitably for most of its time in government hands. Its net profit in 1979 from underwriting and investments was nearly $ 11 million, on assets valued at $127.6 million.54

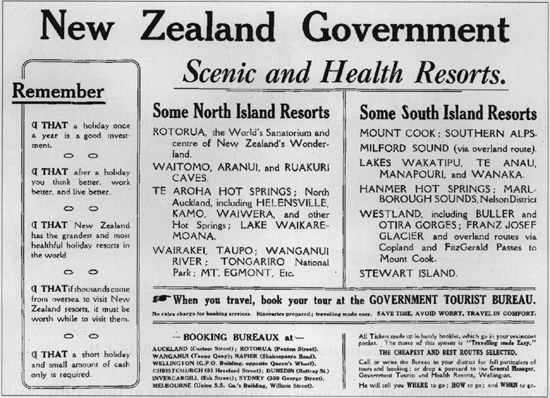

One further Liberal initiative deserves mention. During the late nineteenth century there was mounting international interest in tourism, and also in the supposedly healthy properties of mineral water. Seddon’s ministers, most particularly Ward, decided that there was money to be made from attracting tourists to New Zealand’s many mineral springs. In his 1897 budget the Prime Minister announced the Government’s intention to appoint overseas ‘agents’ to publicise New Zealand. The Department of Tourist and Health Resorts was established early in 1901 as an adjunct to Railways. In April it became an independent department. It liaised with Industries and Commerce, sharing for a time the same Superintendent, T. E. Donne. Already various forms of government assistance had been given to develop thermal springs, such as a subsidy of £150 to help ensure a steady flow of water to the popular Te Aroha Springs. In the 1880s the Government allocated sole rights to a private contractor to draw and distribute the supposedly efficacious Te Aroha mineral water. At Hanmer in the South Island by the turn of the century there was a Government Sanatorium with 22 bedrooms, as well as a lodge and a licensed hotel. They had originally been built by the Government for travellers crossing the pass nearby. More than 2300 people visited Hanmer during the 1901-2 season.55 A rudimentary tourist industry with the State as a major player was emerging.

Government Tourist Bureau advertisement, Christmas 1914.

At first sight it seems strange that a country which today entertains nearly 1.5 million tourists a year with big, privately owned tourist facilities, should need so much government involvement. Yet at the turn of the century there were fewer than 4000 overseas visitors a year, and only a handful of New Zealanders like Ward who had ‘taken the waters’ in Europe appreciated the fascination that Bath, Baden Baden and Aix les Bains held for those with money. Internal travel in New Zealand was arduous and expensive and the domestic tourist market was small. Few private individuals perceived any potential in tourism. To the entrepreneurial Ward, the opportunity to involve the visiting Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York in the opening of the ‘Duchess Pool’ in Rotorua in June 1901, with the British press in attendance, was too good to miss.

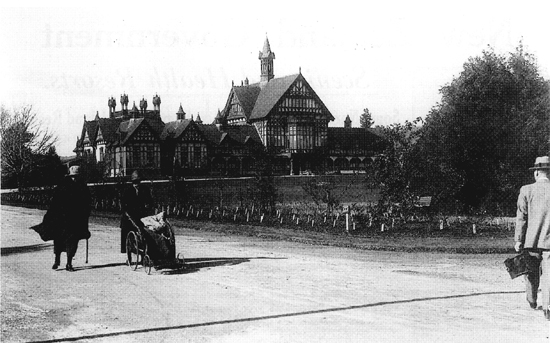

Government sanatorium, Rotorua, 1920s. ATL F-90815-1/2

Ward certainly convinced himself of Rotorua’s curative powers; he and his wife became devotees, never missing an opportunity to visit. From minor village status in 1901 Rotorua expanded quickly, becoming in effect a government town with its own municipal legislation. Dr Arthur Wohlmann had been appointed Government Balneologist in 1898. He spent much of his time in Rotorua reporting on the state of the baths. In 1902 he prepared plans for what came to be known as the Aix Baths. They were necessary, he argued, because some of the public pools were ‘more like pig sties than places for Christians to bathe in’. Construction progressed apace; requests to the minister for authorisation to spend money were answered immediately, sometimes even on the same day. There seems to have been no careful budgeting. Receipts for agricultural exports were moving upwards at a steady rate, state revenue was flowing, and senior ministers often felt free to authorise expenditure of money ‘on the hoof. The Aix Baths were functioning by the early part of 1903 but there were constant closures due to breakdowns in the water pumping system. Repairs proved expensive. In 1908 a new bathing complex was being planned. When finished it contained mud baths, massage facilities, electrical treatment, vapour and inhalation facilities. Wisely, perhaps, a doctor receiving a state subsidy was located nearby!56

Under Ward, the Department of Tourist and Health Resorts became a publicity office for New Zealand, and incidentally, its increasingly self-important minister. Agencies opened in Sydney and Melbourne and in 1905 an advertising campaign was launched in Europe. A pamphlet entitled ‘The Mineral Waters and Health Resorts of New Zealand’ was produced and widely distributed. A sanatorium, several pools, spacious parks and launch trips on the lakes lured nearly 18,000 tourists to Rotorua in 1906. In time, a Tudor-style post office to match the architecture of the bathhouse complex appeared. Tourism certainly helped to ‘kick start’ Rotorua; from 1907 until 1923 it was administered directly by the Tourist Department.57

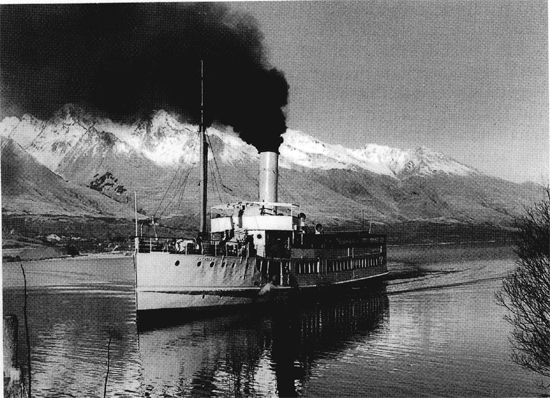

By this time the department had also built accommodation at Waikaremoana and there was a guest house at Waitomo Caves. Steamer services on the Whanganui River were part of an expanding network of North Island tourist attractions. Hanmer Springs, the Hermitage at Mt Cook, steamers on Lakes Wakatipu and Te Anau, and tramping on the Milford Track rounded out the South Island’s attractions. Salmon and trout fishing in several lakes, as well as pheasant and deer shooting, enthused more than the handful of acclimatisation societies who were promoting leisure sports for New Zealanders. Overseas tourist numbers doubled every six or seven years. In 1906 more came from the United Kingdom than from Australia or from the United States.58 New Zealand’s Tourist and Publicity Department of later years enjoyed an early reputation as New Zealand’s pre-eminent tourist agency. For a time it ran the country’s native bird sanctuaries as well.

What is particularly interesting about the early Department of Tourist and Health Resorts is that it did not post profits. In spite of regular adjustments to its fees, most of its services usually operated at a loss. So did the booking services. At a time of adequate government revenue ministers seem never to have regarded the costs of the department as a cause for concern; even the cautious James Allen, who was Minister of Finance in 1912-15 and again in 1919-20, did no more than crow about the rising numbers of tourists, and the ‘thoroughly up-to-date medical apparatus’ recently purchased by the Balneologist. By 1918 the government-owned resorts were losing £20,000 and by 1924, nearly £30,000 pa. This figure continued to rise, the department losing £112,000 in 1930-31. Even with considerable redundancies and adjustments to fees during the depression, losses amounted to £41,000 in 1932-33. During the depression the Government went ahead with an earlier promise by Ward to construct what came to be known as the Blue Baths in Rotorua. They seem never to have made profits and were finally closed in 1982. By 1960 the department needed a subsidy from the taxpayer of £1.2 million to function.59 Successive ministries always believed there was something sufficiently magical about tourism to warrant a departure from Ward’s earlier insistence on an adequate return from state investment.

By the time of Seddon’s death in June 1906 the New Zealand Government had become educator, banker, insurer, facilitator, promoter, provider, guarantor and helpmate of last resort. Cabinet was the all-powerful centre of the country’s activities. Seddon was widely known as ‘King Dick’. His question times in Parliament could range over an array of topics about which he, and his colleagues, were expected to have detailed knowledge. Seddon used such occasions shrewdly; he was never too shy to promote himself or his government. J. C. Beaglehole says that the Premier ‘united within himself a whole orchestra, or, rather, brass band of achievement; and as a performer on the big drum he was without peer’.60 The public admired him; some even loved the portly pugilist. The ministry now bulked large in colonists’ lives. Many begged politicians to do even more. Dr Guy Scholefield wrote about this time:

Scarcely a month passes without some convention passing a cheerful resolution demanding that the Government should step in and operate some new industry for the benefit of the public. Now it is banking: tomorrow bakeries: over and over again some moderate reformers have called upon the Government to become the controllers of the liquor traffic: once upon a time it was importuned to become a wholesale tobacco seller: more than once to purchase steamers to fight the supposed monopoly of existing lines.61

Because it could be both optimistic and cautious, the Liberal Government retained its appeal to the business community, as well as to farmers. As David Hamer observes, Liberal leaders insisted that reform should proceed only as fast and as far as public opinion would allow. While there were faddists in their midst, the ministry kept them under control until its last few years in office.62 Seddon and Ward happily assisted industry, so long as employers and employees agreed that it was in their joint interest. Businessmen enjoyed dealing with Ward; he was credited with safe hands, despite his own bankruptcy in 1897.63 Throughout his life he saw the State as the handmaiden of private enterprise, not its enemy. In a speech to friends in his home town in 1893 he said that by fostering the interests of Southland he was furthering his own interests. That, he said, was what they were all doing. ‘If there was one thing wanted it was that the people of Southland should pull more together than they had ever done in the past. One man might go on faster than another, but that was no reason why he should be tripped; tripping him reacted and retarded the progress of those who tried to trip him.’64 Having the courage of his connections was second nature to Ward. Few pioneers understood what was meant by conflict of interest. In most new countries public and private enterprise strode boldly, hand in hand.

The veteran government steamer, Earnslaw, still plying its trade on Lake Wakatipu, 1951. ATL C-23148

In January 1894 Ward became the first Minister of Industries and Commerce. His job was to promote New Zealand’s trade and to find new markets for produce. The first report of the Industries and Commerce Department was published in 1902.65 Three years later the department was still only small, with three officials operating out of Head Office. But they saw themselves as peripatetic trade facilitators. They helped with shipping and marketing of agricultural produce such as tinned meat, hay and oats to South Africa during the war, and kept a close eye on exports of frozen meat to the United Kingdom. The Secretary of Industries and Commerce explained his role in 1905 as ‘keeping the products of the colony prominently before the consuming markets of the world’. To this end officers were despatched to the St Louis Exposition in 1904-5 with a variety of woollen goods for display. With the assistance of the Agent-General’s office in London, which undertook a great deal of purchasing as well as promotional work on behalf of the Government, exhibits of New Zealand produce were displayed at the Crystal Palace in 1905. So good were the Government’s exhibits that they won several trophies. Industries and Commerce played a major part in organising the New Zealand International Exhibition in Christchurch over the summer of 1906-7.66 The accent was on products from the soil. In 1909 as part of several regroupings of departments, Industries and Commerce was tied to the Department of Agriculture and to Tourist and Health Resorts but its functions were undiminished.

The Liberals maintained their predecessors’ interest in subsidising promising areas of industrial development. Bonuses for the export of canned and cured fish remained in place, the Government paying out a total of £10,981 between 1885 and 1901. In 1894 the Collector of Customs was given the task of assessing whether W. Gregg & Co. of Dunedin had qualified for the bonus offered for the production of 100 tons of starch.67 In 1899 samples of Taranaki iron sand were sent for testing in London – at government expense. During 1905 there were trial shipments of poultry to London to ascertain whether there was a promising export market.68

The Liberal Government also agreed to assist recreation. In 1899 it offered to match on a pound-for-pound basis the outlay by acclimatisation societies to procure supplies of game birds, especially Virginian quail, ruffled grouse and prairie chicken. Such activities led on to the creation of state fish hatcheries and game farms and ultimately, in the hope of recouping the outlay, the issuing of fishing and shooting licences by the Department of Internal Affairs.69 By 1906 the Government was operating experimental farms which researched animal breeding techniques and trained young farmers in up-to-date methods of agriculture. Farmers could have their soil analysed, their milk tested or plants identified free of charge. Over a 20-year period sums totalling £275,393 were spent on experimental farms.70

From 1895 until 1907-8 New Zealand’s exports rose steadily; a slip in the price of one commodity was usually more than compensated for by a rise in another. A recession with its genesis in the United States impacted more broadly on the British market in 1907 and New Zealand’s exports to London declined in total value in 1908. Ward’s Government was obliged to tighten the belt early in 1909, although buoyant trading conditions quickly returned. The recession served only to increase demand for the Government’s promotional efforts. The ministry ensured that a New Zealander was present at the Chambers of Commerce Conference in Paris in 1908, thus encouraging a practice that grew over the years whereby the Government paid for various sector groups to attend overseas conferences that dealt with matters of interest to New Zealand.

Considerable effort was made by Industries and Commerce to negotiate direct shipping with several new markets in Asia. However, the subsidies required for such a service were so heavy that they would have made the trade uneconomic. The Government retreated.71 At the Colonial and Imperial Conferences of 1907, 1909 and 1911 Ward vigorously promoted Imperial trade and shipping, as well as his pet project of Imperial Federation. All his life he hoped that a mutually advantageous common market could be arranged among the British Dominions.72 In those days there seemed no such thing as a cost-benefit analysis; what ministers believed to be good ideas were acted upon. Governments learned by trial and error.

While many wanted the State to promote their interests, others expected it to protect them from danger, especially civil emergencies. Local authorities had been pleading with central government for many years to help with flood relief; the ravages around Motueka in the later 1870s led to some pointed requests for aid which governments rejected at the time.73 Seddon and Ward, however, adopted a different approach when unforeseen tragedies occurred. The ministry established a national appeal to help the families of 65 miners killed in an explosion at the Brunner mine on 26 March 1896. By 1910 the Department of Internal Affairs was dealing with requests for assistance whenever major civil emergencies occurred. On a Cabinet recommendation, pound for pound subsidies were paid to local authorities through the Department of Public Works.

From as early as 1878 the Government contemplated subsidies for volunteer fire brigades.74 The Fire Brigades Act 1906 was the first serious effort to coordinate services variously funded by local authorities, insurance companies and the Government. The Act established an Inspector of Fire Services. Fire boards emerged in mostly urban areas of the country. Once recognised, a board became eligible for limited state assistance. While there was a strongly centralist streak to the Liberals, on some issues they insisted that communities shoulder their own burdens. Fire-fighting was one. The Government stuck determinedly to the principle that communities should provide and support their own fire-fighters. Most brigades got no more than limited funding for equipment, and transport costs to the biennial meetings of volunteer members of the United Fire Brigades Association. However, the number of fire boards increased steadily over the years, with a corresponding rise in the State’s limited outlay.75

The benevolent climate generated by the Liberals led some interest groups to seek forms of legislative protection for their industries. When a conference of fruitgrowers gathered in Wellington in May 1896 they spent much of their time discussing the collegial obligations of growers to each other, and how government should ensure fair play within their industry. Of particular concern to them was the fact that while some growers were taking steps to protect their fruit against pests, others were not. The conference wanted legislation that would guarantee careful growers against the damage that could be inflicted on their produce by the less provident. The request was supported by the press.76 Even staunch individualists saw the State’s use of its regulatory powers as an aid to private endeavour. Several professional groups had already taken steps to license themselves -doctors in 1869, dentists and pharmacists in 1880, and lawyers in 1885. Since 1883 efforts had also been made to license auctioneers and restrict their practices; eventually land agents were also brought under legislative control. Agricultural producers, too, were beginning to discuss the commercial advantages of collective action and regulation, although it was some years before action was taken.

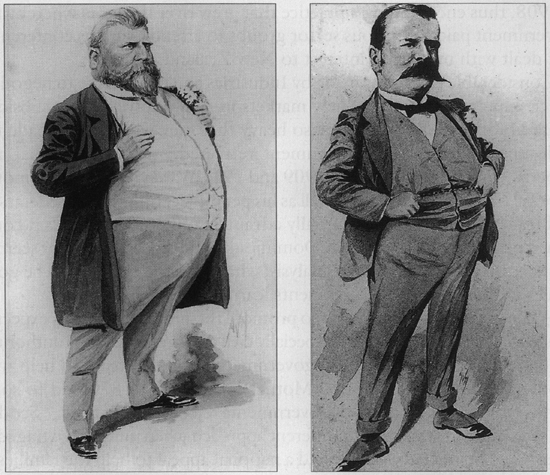

The pragmatists, Seddon and Ward: supreme confidence in a time of Liberal prosperity. ATL F-109511-1/2; F-164121-1/2

As the years went by, the wider New Zealand public welcomed the Liberals’ active, paternalistic State, believing it to be in their general interests. However, the world of Liberal social engineering did not include all its citizens. Policies were Eurocentric. Asians and Maori were not afforded the same solicitude as Pakeha settlers and the Liberal Government maintained rigid, increasingly old-fashioned attitudes towards women. Chinese who had come to New Zealand during the gold rushes numbered 5000 in 1881. Ten years earlier a parliamentary select committee on Chinese immigration had dismissed the more hostile accusations about lack of cleanliness and the supposed threat which Chinese men were to European women and children. Nevertheless, successive governments legislated against Asian immigration. Hostility to Chinese reached its peak during the Liberal years when, ironically, the number of Asians was steadily declining. In 1906 there were only 2570 in New Zealand. The previous year New Zealand’s first racial murder of an Asian had occurred: a madman, Lionel Terry, killed a Wellington Chinese outside his fruit shop.

Asians were excluded from eligibility for the old-age pension until 1936. Progressively higher barriers were erected to stop their migration to New Zealand, including poll taxes and reading tests. Once here, their citizenship status remained in doubt. At first, some gained naturalisation, but by the late 1890s delaying devices were used by the Colonial Secretary’s Office to stall most Chinese applications. The Government became more blunt when Ward became Colonial Secretary in December 1899. He directed his officials to advise Chinese applicants that it was not his intention to recommend naturalisation ‘to persons of the Chinese race’. This remained government policy until the minister went overseas for several months in 1906, whereupon a batch of Chinese applicants received their naturalisation from the acting minister. However, such was the hostility to Chinese by 1908 when the Immigration Restriction Act was passed that the Department of Internal Affairs began telling Chinese applicants for New Zealand citizenship: ‘I am directed by the Minister of Internal Affairs to inform you that it is not considered expedient at present to grant letters of Naturalisation to persons of the Chinese race …’.77 New Zealand’s political leaders adopted an approach that was only slightly less paranoid about the ‘Yellow Peril’ than their Australian counterparts’. While occasional legislative tinkering was necessary because of British sensibilities, official policy remained unwelcoming to Asians until the 1950s.78

While Asians were very much in the Liberals’ line of fire, Maori were largely beyond their vision. Concentrated in many of the more remote parts of the country, the Maori population declined after the wars to the point where by 1890 settlers outnumbered them by fourteen to one. Maori land holdings reduced to about 16 per cent of the total country and nearly one quarter of Maori land was leased to Pakeha.79 It was widely believed that Maori were a dying race. Declining numbers, intermarriage and policies of cultural assimilation led policymakers to expect ultimate amalgamation of the races. Native education was promoted, but it was to be in English. Employment opportunities were ephemeral, depending often on the whim of Pakeha. Living conditions were usually substantially worse than those enjoyed by settlers, and Maori rights to old-age pensions were reduced in 1901. The assumption was that Maori would be be looked after within their traditional extended families. Keith Sorrenson notes that those Maori who shut themselves away from European contact tended to be better off than those who involved themselves. Sometimes a Pakeha ‘Good Samaritan’ would take up their cause,80 but most relied on the support of their iwi.

After 1896, when the Maori population began rising once more, some social agencies started to adopt a more inclusive policy. Maori health came under the aegis of the Department of Public Health, and two distinguished Maori medical officers, Peter Buck (Te Rangihiroa) and Maui Pomare, pushed ahead with campaigns to improve hygiene and sanitation. The incidence of infant mortality and tuberculosis, however, remained significantly worse for Maori than European.81 While the Liberals embarked on a large purchasing programme of Maori land, particularly in the North Island, ministers began to show greater willingness to listen to Maori land grievances. In 1905 under the Maori Land Settlement Act, state loans were made available to Maori to develop their lands. Ten-year loans of one third of the assessed value were lent at 5 per cent interest.82 However, the Crown’s resumption of Maori land purchase in the same year gave rise to varying forms of opposition among tribes, some of which endeavoured to reopen compensation claims for land confiscated at the end of the wars of the 1860s. With the election of 1911 on the horizon, Taranaki Maori in particular began searching for alternatives to the Liberals. Dr Maui Pomare had developed close ties with the Reform opposition and emerged as their torch bearer.83 Ultimately, he and his colleague, Gordon Coates, worked with the young Liberal lawyer and parliamentarian, Apirana Ngata, to gain some measure of recognition of Maori claims. The Liberals passed out of power in 1912, largely unlamented by Maoridom except in Ngata’s electorate, where significant numbers had benefited from the State’s assistance to agriculture and tourist promotion.

Nor was the Liberal era one of empowerment for women. By the early years of the twentieth century women were beginning to enter the professions. They formed approximately 50 per cent of the teaching profession, and several women doctors were on the Department of Health’s payroll in its early years. After passage of the Female Law Practitioners’ Act in 1896 women lawyers slowly entered practice.84 But progress within the public service was slow. The first woman had been appointed to the public service in 1876. Increasing use of typing within the public service opened up some career opportunities for women. However, until 1962 women received less pay for the same work than men. Some men opposed them having the right to join the Public Service Superannuation scheme where they enjoyed the option of earlier retirement. The advent of award wages in the private sector made employers wary of employing women. Their percentage of the work force dipped for a time. Edward Tregear, one of the high priests of Liberal reform, saluted this trend. In 1908 he wrote: ‘In my opinion, the less the future wives and mothers of the nation have to encounter industrial toil and enter into industrial competition with men the better.’85 Having said this, however, Tregear bemoaned the falling birth rate and what he believed would be an inevitable future shortage of men for the workforce – a conundrum that he and others of like mind seem never to have worked out to their satisfaction. While many Liberals supported women’s suffrage in 1893, they did so not out of a belief in the rights of women but rather in the vague hope that women might restrain, even reform, colonial men.86 Votes were one thing; it would be many years before governments espoused the cause of equal rights.

Farming always depended on women’s work; a Waikato milking shed in 1911. Wagener Museum

By 1912 Ballance, Seddon, Ward and his short-lived successor, Thomas Mackenzie, had built a complex additional structure on top of the substantial state edifice they inherited in 1891. By a variety of pragmatic interventions the Liberals hoped they had produced a more protective, congenial society in which New Zealanders could thrive. The results seemed heartening. While the country’s total population grew by approximately 64 per cent during their years in office, the GNP rose 126 per cent over the same period. Buoyant export markets meant that for all but eight of their 21 years in office the Liberals witnessed real economic growth; in nearly half of those years growth exceeded 3 per cent pa.87 However, it was not a cheap exercise. Both Seddon and Ward borrowed vigorously to support their experiments. In 1890 the country’s net indebtedness was £37.28 million. By 1912 it had reached £82.24 million, of which £16.8 million represented money that had been on-lent by State Advances. Debt repayment was a constant political issue, especially during Ward’s prime-ministership between 1906 and 1912.88

The economy was booming when the Liberals left office, but so too was inflation. Ward’s Government decided to explore uncharted waters in 1910 when it passed the Commercial Trusts Act, which made it an offence to charge prices for flour, meat, fish, coal, sugar, oils and tobacco that were ‘unreasonably high’. What constituted a ‘reasonable’ price was not defined, nor was there any mechanism established to police prices.89 In some desperation during its last weeks in office the Liberal Government appointed a Royal Commission on the Cost of Living. Its members were strong believers in an active State; besides Tregear, two new Labour MPs were among the commissioners. They believed that by tinkering with rules, regulations and legislation, social outcomes could be improved. They concluded that there had been an increase in the cost of living of at least 16 per cent since the middle of the 1890s, but that it was approximately the same increase that had occurred in Great Britain, New Zealand’s main trading partner. The commissioners suggested a host of interventions in the economy that could reduce workers’ living costs, including an end to tariffs on foodstuffs, the creation of municipal markets and an extension of the Workers’ Dwellings scheme. But there was uncertainty on one point: could prices continue to be pushed up by rising wages, and if so would they not make New Zealand’s exports uncompetitive in the longer term?90 Delivered to ministers in August 1912, a few weeks after the Liberals left office, the report contributed to a growing debate among social reformers. However, there is little evidence that the new Government took much notice of it.

In 1911 Ward budgeted for a small surplus. The Liberals never believed in setting aside much money, even in prosperous non-election years. A Public Debt Extinction Act was passed in 1910 which created what was called a Sinking Fund from which money was invested domestically with a view to earning a higher rate of interest than could be got overseas. The goal was to extinguish the public debt over 75 years.91 New Zealanders had fallen into a pattern of living right up to, and beyond, their income. Yet, few thought government spending excessive. The Reform Party opposition promised to spend more.

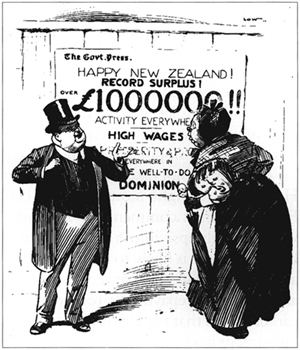

David Low captures Sir Joseph Ward in election mode, 1911.

Although the State was beginning to encounter problems, overseas commentators continued to visit New Zealand. Most still liked what they saw. Peter Coleman notes that what made Northern Hemisphere reformers sit up and take note was the fact that New Zealand’s state involvement in the economy ‘was so comprehensive in scope and so rapid in implementation’. A Scotsman, Hugh Lusk, who had briefly been a New Zealand MP in the 1870s before taking to the American lecturing circuit, became a publicist for the antipodean reforms. In 1913 he published a book called Social Welfare in New Zealand. He pointed to the country’s ‘great social and political experiment at once unique in character and remarkable in its effects’. After surveying the Government’s efforts at ‘State Socialism’ he concluded that New Zealand was an ‘object lesson’ for other countries, especially the United States.92 Peter Coleman mentions others who came in later years, who returned to the Northern Hemisphere as propagandists for the ‘New Zealand Way’.

However, some observers found flaws in the system of State Socialism. Writing in 1910, the Dunedin lawyer, William Downie Stewart, and an American academic, J. E. Le Rossignol, observed that on the available evidence, governments were seldom as efficient as private enterprise when it came to managing enterprises. They drew attention to the criticisms that were now being levelled at Australia’s state employees, whose easy-going pace of work was often referred to as ‘the Government stroke’. And they warned against sloppy accounting by government businesses.93

This was a point taken up in 1916 by an American, Robert Hutchinson. He had spent eight months in the country the previous year. Echoing Frank Parsons’s comments of a decade earlier, Hutchinson noted: ‘The value of a glimpse into a country like New Zealand is that we can see a little of what it is likely to be further down the road than we ourselves are at present.’94 He was worried about New Zealand’s level of indebtedness, and the large repayments required on loans. Moreover, despite Ward’s earlier claims that the Government was getting a return of 3 per cent on its investment in railways, Hutchinson questioned whether those returns were accurate.95 It was a perceptive observation. While State Mines were still making a profit, the Department of Tourist and Health Resorts continually lost money. State trading organisations had many worse times ahead of them. But for the moment, New Zealanders were enjoying one of the highest living standards in the world and many envied this. Could these living standards survive a serious downturn in commodity prices? It was some years before it became clear that while the State could achieve some things, it was not omnipotent.