The British historian A. J. P. Taylor began his history of early twentieth-century England with the words, ‘Until August 1914 a sensible, law abiding Englishman could pass through life and hardly notice the existence of the state, beyond the post office and the policeman.’1 As we have seen, this could not be said of New Zealanders who, since the 1840s, had witnessed one piece of state intervention after another. However, nothing that had occurred so far in either country could have prepared people for the hold which the State was to establish over them as a result of World War I. While that grasp relaxed a little when peace returned, it was not to slacken substantially until the 1980s. ‘The rise of collectivism’, as Robert Skidelsky has called it, took on an inexorable quality everywhere after 1914.2

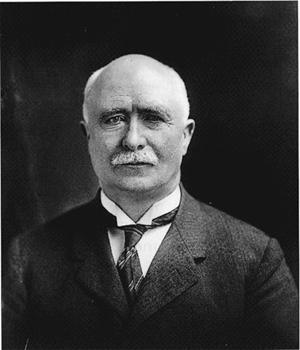

On 10 July 1912 the New Zealand Liberal Party finally surrendered office after more than 21 years in power. A bluff Orangeman, William Ferguson Massey, a South Auckland farmer, replaced Thomas Mackenzie as Prime Minister; the austere Cambridge-educated Anglican businessman, James Allen, became Minister of Finance. He believed passionately in the doctrine of individual initiative. A lawyer and freemason, Alexander Herdman, a crusader for public service reform, became Minister of Justice; and Francis Dillon Bell, New Zealand’s first King’s Counsel, who had been Crown Solicitor in Wellington, was the new Government Leader in the Legislative Council. Sir Joseph Ward, who had played a major role in nudging government into many corners of the economy, retired to the Liberal Party’s back benches for twelve months before becoming Leader of the Opposition.3

Both in ideology and experience the new Government presaged change. Yet surprisingly little altered. The only noticeable differences were inexperienced faces at the Cabinet table, a new system of public service classification introduced soon after Massey came to power, and two gestures towards Reform’s faith in individualism – the freehold option for farmers holding leases-in-perpetuity, and a tougher approach to striking trade unions at Waihi and on the waterfront during 1912-13. In other respects, during its sixteen and a half years in office, the Reform Government wound the ratchet of state interventionism a little tighter.

W. F. Massey, Prime Minister 1912-25. ATL G-1540-1/1

It is not hard to explain why the State did not retreat after 1912. First, the Reform Party had not promised revolution. There was no mood within the party to undo the relationships that had grown up between the State and interest groups, only to adjust them. In opposition Reform had concentrated on the overtly political nature of the Liberal Government’s public service and had exploited growing concern among farmers about the increasingly rigid approach to land tenure taken by the Liberal Government. Massey was not opposed to big spending by government; he sought only to redirect Public Works construction towards farming districts and to help the rapidly expanding North Island economy.

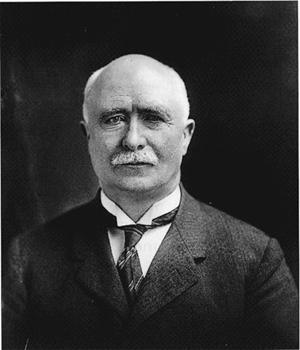

But even had there been a desire fundamentally to alter New Zealand’s economic direction, the Reform Government was seldom in a position to contemplate it. From the middle of 1912 until the election of 1914 Massey had a constant struggle to survive and most of his Government’s internal politicking was directed at firmly attaching to Reform those independent Liberals whose votes helped him to office in July 1912. Important to achieving this end was another state experiment. Three northern independents were instrumental in having a Royal Commission into the Kauri Gum Industry established in March 1914. The Kauri Gum Industry Amendment Act 1914 resulted. It authorised the Ministry of Lands to advance up to 50 per cent of the assessed likely export receipts from gum to diggers. The department would take possession of the gum and sell it on the diggers’ behalf, in much the same way that producer boards were to operate in the 1920s. A departmental spokesman later asserted that this new policy ‘has had a beneficial effect on the industry, and this fact is generally recognised by the producers – the gum diggers and the small farmers’. He could have added the local politicans as well, for Vernon Reed, Gordon Coates and T. W. Rhodes had, by this time, become warm supporters of the Reform Government.4

Regulations governing economic activity were growing in number by 1900; a gum digger’s licence. Wagener Museum

The formation of a National Ministry on 12 August 1915 to assist with the war effort removed any prospect that anything controversial could be advanced until the bi-partisanship collapsed on 12 August 1919. During the intervening four years the Liberals once more held several key portfolios. Ward and his colleague, the Auckland brewer Arthur Myers, ran the war economy. It was not until the election on 17 December 1919 that Massey won his first substantial victory. However, a serious recession quickly set in. Over the next five years the simple act of survival proved, in Massey’s own words, to be ‘hell all the time’.5

In any event, no matter what hopes a few conservatives might have nursed, Massey’s Cabinet showed the same incremental approach to state activity as its predecessor. Reform backbenchers supported him. Parliamentary debates reveal that most Reform MPs wanted simply to redirect the attention of the State towards their areas of concern. One announced that ‘there is no such thing … as Conservatism or Toryism in this Dominion’; another argued that the real liberals were sitting on the Reform benches.6 Allen’s first budget, on 23 August 1912, was cautious. While the new government would borrow less, it would maintain an active railway construction programme, pursue closer settlement of the land, and expand the country’s state-funded health services, especially to rural areas. The Government would spend more on irrigation schemes, provide better educational opportunities for young farmers, and restructure, rather than sell, the Government’s experimental farms.7 A Board of Agriculture was soon empanelled consisting of a number of friends of the Reform Party. Its function was to make recommendations to Government on issues of vital importance to the rural sector. As its reports show, it was soon struggling to justify its existence.8 The Board of Agriculture was a forerunner of many such quangos that were appointed for political purposes during the rest of the century.

A subsidy was introduced in 1913 to help the emerging fruit preserving industry, while ministers boasted about their big spending on draining 39,000 acres of the Hauraki and Rangitaiki Plains. In November 1914 an Iron and Steel Industries Act was passed. Its intention was to encourage the manufacture of iron and steel by the payment of bounties on pig iron and ‘puddled bar iron’. In the same year the Government offered grants to assist private companies prepared to drill for oil. Several companies quickly lodged applications. These moves were simply extensions of the now traditional policies built up since Stafford’s day.

The Reform Government’s health policies were built on Liberal foundations. A substantial public hospital rebuilding programme was soon under way. More St Helen’s hospitals were constructed, and authority to engage in slum clearance was taken under the Public Health Amendment Act 1915.9 All this state activity suggests that a degree of consensus was emerging that governments were expected to play a dominant role in the country’s life. Reform’s Liberal opponents often gave the impression of opposing for the sake of it.

The outbreak of war in 1914 lifted Reform’s dirigiste tendencies to a new plane. A huge public outpouring of imperial sentiment led politicians in all parts of the British Empire to sanction full use of the State’s powers to win the war. An expansion of central authority was not unique to the British Empire. Robert Higgs in his classic Crisis and Leviathan argues that in the United States there was ‘an enormous and wholly unprecedented intervention of the federal government in the nation’s economic affairs’ between 1916 and 1918. He claims that the growth of centralist tendencies during those years far outstripped those of the Progressive era over the previous twenty years.10 This was also the case in the United Kingdom and in New Zealand.

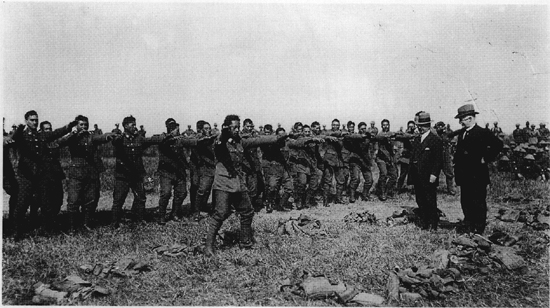

The Governor, Lord Liverpool, flanked on his right by Sir Francis Bell and W. F. Massey and on his left by Sir Joseph Ward, declaring New Zealand to be at war, 5 August 1914. ATL G-48457-1/2

On 5 August 1914 the Governor, Lord Liverpool, read the proclamation of war from the steps of Parliament Buildings to a crowd of 15,000 cheering enthusiasts. Five days later Parliament passed the Regulation of Trade and Commerce Act. It was designed to give ministers the power to fix maximum prices by orders-in-council for the duration of the war. Selling goods in excess of maximum prices became an offence punishable by a fine of £500. On 23 October 1914, without any debate, Parliament passed the War Regulations Bill. Along with further amendments in 1915 and 1916, this measure gave the Government wide powers to gazette regulations affecting virtually every area relevant to the conduct of the war. Under the guidance of Solicitor-General, J. W. Salmond, who was a pronounced centralist, the Government took the powers to regulate on any matters deemed ‘injurious to the public safety’. The Ministry could require companies to manufacture military supplies, and could involve itself in social areas such as the suppression of prostitution, the sale of liquor, and the prevention of venereal disease.11 In Part 1 of the War Legislation Act 1916 Parliament armed itself with a complex piece of legislation to control rents at their level on the day before the outbreak of war. Parliamentarians were voting powers to the Government never contemplated in peacetime. Once gained, such powers were seldom abandoned.

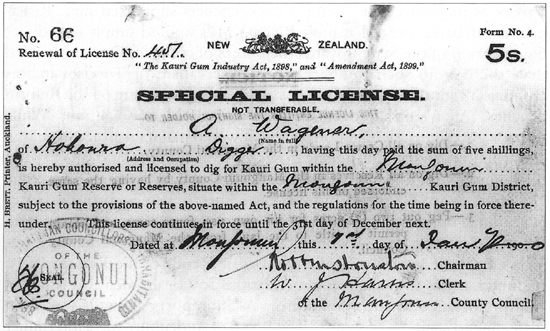

Ward and Massey meet the Pioneer Maori Battalion in France, 1918. ATL G-13283-1/2

About 14,000 men volunteered in the first week of war. On 16 October 1914 after a brief stint in camp, 8000 New Zealanders, jocularly known as ‘Bill Massey’s Tourists’, sailed for the Middle East.12 It was not until the middle of 1919 that those who remained of the 124,211 men who served in World War I were back in New Zealand. The official estimate of the monetary cost of participation was £79,289,454 for a country of 1.2 million people.13

There were no precedents for handling the sudden switch in economic priorities that war demanded. Massey’s Government felt its way, believing that hostilities would soon be over. When this likelihood faded, and the Government’s majority remained precarious, especially after the General Election on 10 December 1914, there was talk of the need for a coalition with the Liberals. In August 1915, Sir Joseph Ward finally agreed.14 By this time the Government had already taken the power to raise extraordinary loans for the prosecution of the war. They were secured against reserves in London. In all £68.5 million was borrowed, much of it domestically. This brought the Government’s total indebtedness to £201 million by 1920.15 The rest of the cost of the war was raised by taxes levied after Ward became Minister of Finance on 12 August 1915. A graduated income tax was introduced in his first budget; the lowest paid were levied 3 per cent of gross wages, while the highest paid (those above £5,600 pa) were levied 10 per cent plus a temporary super tax that amounted to another 3 per cent. Many other taxes were levied in the same budget. They included an additional tax on profits made from farming because farmers were now earning big returns from the British commandeer of farm produce that came into effect in March 1915. Railway and Post and Telegraph charges were also raised, and duties were imposed on new cars, motor spirits and alcohol. Death duties, stamp duties and totalisator levies all increased. Ward set in place most of the taxes that were to be a feature of budget nights for the next 70 years. Interestingly, they were levied purely for revenue and were unrelated to the cost or use made of the goods or services.16

Much interest centred on Ward’s promise to tackle rising inflation which began to emerge as a problem within days of the outbreak of war.17 Soon after taking office, he assured Parliament that the Government would legislate ‘to ensure that the cost of food, clothing, and shelter of the people [is] in no way unduly or artificially increased’. He was signalling an extension to his own Commercial Trusts Act 1910 and to Massey’s Regulation of Trade and Commerce Act of 1914, neither of which had so far succeeded in holding down prices. Ward told his colleagues:

Our desire should be that no part of the field of business opportunity may be restricted by monopoly or combination, and that the right of every man to acquire commodities, and particularly the necessaries of life, in an open market, uninfluenced by the manipulation of trust or combination, may be preserved, and the people not exploited.18

Ward’s view reflected concerns felt in New Zealand and overseas that private monopolies were interfering with the market place, and that the State needed to stop the exploitation of ordinary people. The National Government’s involvement in price control became wide-ranging. Ward signalled his intention to give traders some competition by increasing the powers of local bodies in line with the recommendations of the 1912 Royal Commission on the Cost of Living. By regulation boroughs could be granted the powers to inspect, sell and control local supplies of milk, to establish and maintain city markets, refrigerate meat, set up bakeries and equip fishing trawlers. With the prior permission of the Minister of Internal Affairs, local authorities could fix charges for services as they thought fit. In adopting these measures Ward was responding to the views of some of the trade unions and Labour MPs. Confidence that public intervention in the marketplace could ensure good outcomes had become axiomatic.

The Cost of Living Act became law on 12 October 1915. It established a Board of Trade which, unlike its predecessors, had powers of investigation. The wartime Board of Trade could inquire into ‘every article of food for human consumption and every ingredient used in the manufacture of such articles’. However, it was made clear that costs beyond the producer’s control were outside the scope of an inquiry. While some ministers such as Bell were less than enthusiastic about the Bill, feeling that it was unlikely to achieve what Ward hoped of it, the sole unionist in the Legislative Council felt the Government was on the right track and should have gone further. J. T. Paul regarded the Board of Trade as a first step towards civilising society. There was, in his view, a philosophical principle at stake. It was

whether any man has an absolute right to do what he likes with his own. So far as his own affects the material and social interests of the community, his property and his business have to be subordinated to the interests of the community. After all, anarchy is only individualism carried to its logical conclusion. … If this Bill does nothing else, it says to certain sections of the community, ‘You shall not do what you like with your own’.

The defect of the Bill in Paul’s view was that it stopped short of examining the true costs of production, and was a compromise with his socialist objective, which was the ‘scientific control of industry’: ‘Either we must follow our present system of production and distribution or we must, as far as possible, introduce scientific methods…’.19 This was a well-articulated expression of views that were gaining currency amongst some unionists, many of whom became important figures in later social engineering.

As the war moved into its second and third years both Bell and Paul -viewing the issue from different ends of the political spectrum – had reason to be cynical about the Board of Trade. A three-member board, which Prime Minister Massey occasionally chaired, took office on 16 March 1916. For some weeks the Government’s Assistant Law Draftsman struggled to devise regulations to define the Board’s powers. He finally admitted that his draft regulations were ‘so elaborate and technical that they will if adopted tend to hinder rather than promote’ the Board’s objectives. Massey accepted the argument that the Board could be considered to be a ‘permanent commission of inquiry’ and it proceeded for a time without regulations. However, having had costs beyond a producer’s control eliminated from its scrutiny, the Board found itself powerless to control the steady upward trend in prices. Establishing what might be a ‘fair profit’, something which Ward had described as ‘an exceedingly difficult matter’, was also beyond it.20 A world shortage of shipping pushed up freight rates, adding hugely to the cost of New Zealand’s imports, and consequently to all manufacturers’ costs. Coupled with the fact that high farming returns from exports were also fuelling inflation, the Board’s task of controlling prices became virtually impossible. Ward conceded in June 1916 that there was little chance the Board would be lowering prices in present circumstances.

Instead, during the next two years the Board of Trade narrowed its focus. It tried, rather ineffectually, to prevent speculation in food and clothing. In 1917 and 1918 the Board imposed maximum prices on flour, bread and bran. The most enduring of these controls were those relating to bread prices which began on 19 March 1918.21 An arrangement was also made with wholesale grocery merchants to control the prices of 57 basic food items. These were allowed to increase in price only with the Board’s permission. The Board turned its attention to clothing in 1918 and investigated the possibility of producing a cheaper ‘standard cloth’. A strong suspicion developed in official quarters that some lines of clothing were being hoarded, and that drapers were making exorbitant profits.22 However, it was soon clear that inflation was sufficiently rampant that the Board had no option but to approve clothing price increases. And with each approval, union anger grew. The last year of the war was marked by industrial unrest in many parts of the country as wages slid further behind prices.23

Once committed to a line of action both politicians and the public found it difficult to resile. After the collapse of the National Ministry in 1919 Massey struggled valiantly to make good on his earlier promise to deliver effective price control. Faced with rocketing inflation and a difficult election, the Government passed a new Board of Trade Act. Now in opposition, Ward’s Liberals had no option but to support it. Subtitled ‘An Act to make better provision for the Maintenance and Control of the Industries, Trade, and Commerce of New Zealand’, it gave formal recognition to a separate Department of Industries and Commerce which had previously been linked with Agriculture and Tourism.24 The new Act retained the Board of Trade and expanded its membership to four. Once more the Prime Minister, or in his absence another minister, presided over its deliberations, again in the hope that tough decisions could be taken immediately.

The restructured board was given wide regulatory powers. It could prevent or suppress methods of competition considered prejudicial to an industry, and could fix maximum or minimum prices for goods and services. It became an offence for anyone ‘who, either as principal or agent, sells or supplies, or offers for sale or supply any goods at a price which is unreasonably high. For the purposes of this section the price of any goods shall be deemed to be unreasonably high if it produces, or is calculated to produce, more than a fair and reasonable rate of commercial profit….’ Hoarding goods was banned.25

For many years now unionists had been arguing that the level of wages set by the Arbitration Court should take account of an employer’s ability to pay. Now a government-appointed board had the power to decide what were ‘reasonable’ or ‘unreasonable’ profit margins. Marketplace considerations were being squeezed out in favour of social and political priorities.

The Board of Trade Act 1919 moved further across uncharted territory and provoked considerable public debate. The Dominion told its readers that the legislation ‘is a measure of considerable promise’, an opinion supported by the Evening Post. The paper from the biggest commercial centre, the New Zealand Herald, also cautiously endorsed the new Board of Trade. However, the Christchurch Press vigorously opposed the legislation, bemoaning what it argued had been a wholesale surrender of power by parliamentarians to the executive during the course of the war. Worse still, in the eyes of the Press, was the prospect that commerce and industry were being brought under ‘bureaucratic control’. The Otago Daily Times was just as vociferous in opposing the new legislation. At best, the commercial world was divided, many observers suspecting that this could be a turning point in the relationships between business and government.26

Armed with very wide powers, members of the new Board tentatively took up their battle stations. Massey informed them in a memo on 24 November 1919 that he expected action to control prices ‘at once’. With the election only weeks away, the Prime Minister announced that he was looking forward to a ‘downward revision in wholesale and retail prices’.27 However, the reforms to the Public Service that his own government had made in 1912 reduced the capacity of politicians to control appointments. The Public Service Commission eventually appointed two investigating accountants to undertake the Board’s work, but they were unable to start for several weeks. By January 1920 ministers were becoming agitated at the slow progress. Massey was convinced that extensive profiteering was occurring, yet the Board was still not up to speed; further staff appointments were still pending.

After some weeks of intensive investigation the Board reported to an impatient Prime Minister that controlling prices was very difficult. They told him that ‘no satisfactory price control can be established or maintained without the controlling authority also having control of the supplies’. While this was a view held by many, it was finally forced upon the department by several court rulings in cases where aggrieved businessmen accused of profiteering had sought rulings from magistrates. Moreover, by the middle of 1920 efforts to control the prices of sugar, timber, coal and cement were running up against world shortages in these commodities. Even harder to combat was the fact that some suppliers stockpiled or redirected stock to foreign markets where profit margins were not so tightly regulated.28 The international marketplace seemed always able to find ways to circumnavigate Massey and his social engineers.

Efforts to control the price of coal were no more successful. On 26 May 1916 the Board of Trade established an inquiry into soaring prices in Auckland. It soon concluded that coal price movements since 1914 were ‘wholly warranted’. Before long, however, industrial action in the mines held up supplies, thus compounding difficulties. Since coal was a major item in domestic heating, it was not surprising that the new Board returned to coal prices in the inflationary months of 1920. Once more the Board carefully scrutinised price movements, and in several cases requested balance sheets from coal merchants to see whether ‘unreasonable’ profits were being made. No evidence was uncovered.29

In his reports to the Prime Minister, the senior commissioner of the Board of Trade, W. G. McDonald, remained optimistic that if he only had more staff he could produce an effective system of price controls. In June 1920 Cabinet, which had been struggling to reduce public service numbers, broke its ban on new positions and approved extra staff. Bureaucrats at Industries and Commerce vigorously promoted price control. The Secretary wrote:

In some quarters the Department is faced with an appeal for the relaxation of all State control, so that business competition may be unrestricted. Among the majority of businessmen there is a genuine conviction that… competition is the best remedy for our post-war difficulties. What these people frequently overlook is the fact that competition seldom, if ever, works freely, and Government interference is one of the minor conditions limiting it. In fact, businessmen themselves are showing a very prevalent tendency to combine and agree for the purpose of eliminating many of the important features of competition. The Department has considered this matter from time to time, and it cannot agree that the total removal of Government restrictions will be either welcome or beneficial. The experiences of war have shown many opportunities for cooperative effort, especially in relation to the organisation and development of the secondary industries in the Dominion.30

However, despite bureaucratic encouragement, McDonald was soon obliged to abandon price setting except for bread, which remained controlled for many more years. The Board resorted instead to publicity about prices in the hope that consumers would use the information to shop about.

The crisis soon passed. Towards the end of 1920 world prices subsided and there was a sharp recession. Falling prices applied a regulatory regime more effective and hurtful for many than anything the Government could have devised. However, for 60 years to come politicians and bureaucrats strove to develop a workable system of price control. In part this was due to the prolonged influence of Dr W. B. Sutch, whose Ph.D. thesis at Columbia University in 1932 was about the experience of price control in New Zealand. Throughout his life Sutch favoured social control and had a deep distrust of the capacity of market forces to advance human welfare. He argued that the Board of Trade had been successful in some areas during World War I, especially with sugar and wheat where there had not been too many ‘middlemen’. As experiments in price control failed in later years, he constantly sought refinements to the system. Many governments accepted his advice, and a wide variety of measures were tried after 1935.31

Meantime, both the Board of Trade and the Department of Industries and Commerce were engaged in other activities that affected the shape of the New Zealand economy. Concerned about the numbers of returned servicemen requiring employment, Massey asked the Board to report on the state of industry, to publish information that might be of assistance to them, and to procure ‘by means of regulations … the due control, maintenance, and development of such industries’.32 An Industries Committee had already been set up by Parliament in November 1918 to foster industry. In a lengthy submission to it dated 31 January 1919, Dr C. J. Reakes, principal officer of Industries and Commerce, presented a number of suggestions for future action. His list consisted of import substitution industries and exporting ventures where value added to goods in New Zealand could provide local jobs. One of his suggestions, the establishment of a cotton mill, was to be discussed for another 40 years, leading to an aborted effort to set up a mill at Nelson in the early 1960s with government assistance. Another of Reakes’s suggestions was that the Government should attempt to push beyond earlier research (‘not encouraging’) into the establishment of a sugar beet industry. He also had hopes for a vegetable oil industry and a chemicals industry to supply local needs.

Ultimately of more significance was Reakes’s suggestion that efforts be made to promote fruit-canning and tobacco-growing. Some small plantings of tobacco in Hawkes Bay had ‘given good results’, he claimed, and the earlier small subsidies to fruit preservers were proving successful. Reakes also pushed for more research into the use of forestry by-products. He was adamant that paper and stationery products could be made locally, and believed there was a future for furniture-making that used New Zealand’s native timbers. He made a similar case for leather.33

Reakes’s suggestions came at a time when interest was mounting in scientific and industrial research. This was being promoted from abroad as well as by the New Zealand Institute, which was a group of scientists that had enjoyed a government grant of £500 pa since 1869 enabling it to publish its findings. The Industries Committee strongly recommended that a Board of Science and Industry be established to coordinate research throughout the country. However, much of the wartime hype that drove state experimentation waned in the early 1920s with the onset of recession and a fall in government revenue. Establishment of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research was delayed until 1926.34 The political will to drive industrialisation flared only spasmodically during the 1920s.

In the face of falling overseas prices, ministers were trimming budgets by the middle of 1921. Serious consideration was given to abolishing the Board of Trade. The Department of Industries and Commerce also came under fire. There was consternation in the manufacturing world as news of these possibilities spread. On 1 December 1921 the Industrial Association of Canterbury wrote to the Minister of Industries and Commerce, E. R Lee, telling him that the manufacturers of Canterbury viewed such talk ‘with considerable alarm’; the work of Industries and Commerce was ‘highly valued’. Lee responded that nothing more than amalgamation with another department was being considered. But that possibility, too, brought opposition from manufacturers, who were beginning to see in the department a guardian of their special interests. Ministers backed off. However, the work of the Board of Trade, particularly its price surveillance activities, scaled down at the end of 1922 with McDonald’s retirement. A senior officer, J. W. Collins, told the new Minister of Industries and Commerce, William Downie Stewart, that the department simply lacked the personnel to handle complaints, and that some businesses – he cited Northern Roller Mills – were not cooperating with the Board, and were refusing access to their books. The Cabinet agreed to amend the Act, believing that the return of a more stable economic environment no longer required a standing Board. The Board of Trade Amendment Act 1923 transferred its price surveillance powers to the Minister of Industries and Commerce. The minister could establish a Board if need be; once one had been set up it could conduct what amounted to a judicial inquiry into prices.35 Price controls, principally covering bread, were occasionally gazetted, but others were repealed. By 1933 only seven sets of regulations under the Act continued in force.

However, the experience of the wartime Board of Trade was instructive. In a recent study of the World War I economy, A. J. Everton concludes with the words: ‘In most cases the interventions were … unnecessary, unsuccessful in that they did not attain the desired end, or counter productive, in that they aggravated the problem they were intended to remedy, or all three….’36 It took many years for politicians to learn these lessons. There was greater success with price control during World War II but it came about in the context of a massive economic stabilisation exercise, something that was tolerable only in emergency circumstances. The history of price controls in peacetime has never been reassuring.

The wider role of Industries and Commerce was another matter. Reakes’s submissions to the Industries Committee in 1919 reflected the growing public belief that governments had a responsibility to promote conditions where industries could flourish. The provision of jobs, and the saving of precious foreign exchange were matters much discussed. While many manufacturers resented what they saw as busybodying by the Board of Trade, most liked the access to ministers and officials which the bureaucratic structure afforded them. Regional manufacturers’ associations and ultimately a national federation emerged during the 1920s. The practice of inviting ministers to industry functions developed. At conferences and dinners regular refrains were sung: protection was essential, and the public should be encouraged to buy ‘Our own first, British second, foreign last’.37

The Department of Industries and Commerce reflected these views. Drawing on their wartime experience, officers were developing and promoting an economically interventionist culture, with a distinctly nationalistic bias. Long before Sutch joined the department it was a strong advocate of protection, state funding and any other form of assistance that might broaden the base of the New Zealand economy, or save foreign exchange. Public servants, many of them inexperienced in the world of factories, commerce, domestic or export trade, promoted views acceptable to politicians, producers, the public, and ultimately their own advancement. In the process they had a major impact on the direction taken by New Zealand manufacturing. The country was beginning to enter a cosy, some felt smug, era where the respective roles of the players became blurred. Bureaucrats and businessmen talked with each other, and then to the politicians; all of them then consulted the Minister of Finance. After arriving at a conclusion – one that would usually cost the taxpayer – they jointly informed the public of what had been decided, supposedly for the greater good. This relationship lasted another 60 years until subsidies and controls were largely abolished. Soon after, the department which was then known as Trade and Industry, was abolished as well.

The impact of World War I on New Zealand extended well beyond manpower and prices. Issues more personal to people could not be avoided. When the troops departed to the front they dislocated lives, families and financial commitments. Servicemen’s mortgage payments were in danger of falling behind. The Government stepped in. In the Mortgages Extension Act passed on 14 August 1914 the rights and powers of mortgagees were limited for the duration of the war. Mortgages could not be called up, nor actions commenced; the sale of a mortgage was prohibited, as was entering into possession. Only interest on a mortgage needed to be paid. As the war dragged on, the life of the Act, intended initially to be one year, was extended until it was finally repealed in 1919.38 The Act was a legislative intervention between mortgagor and mortgagee that riled some, and was recalled when similar interventions were undertaken by the Coalition Government during the Depression.

Contributions to the National Provident Fund and to friendly societies were equally vulnerable to wartime dislocations. By the end of 1915 more than 1500 contributors to the National Provident Fund had left for the front. Having preached the gospel of self-help, the Government found it had no option but to assist. Massey’s Government decided to pay into the fund a sum equal to half the servicemen’s contributions during their absence.39 Friendly societies were already pressured by competition from the NPF and the more generous array of benefits it paid. By March 1917 the absence of 5488 friendly society contributors was causing them serious cash problems. Already in November 1914 the Government had decided to subsidise the reinsurance of death benefits that the societies offered – a promise that during the first three years of war cost the Government nearly £12,000, and led to the establishment of the Departmental Reinsurance Fund.40

By 1917 many friendly societies were struggling to keep their soldiers in ‘good standing’ with their sickness funds. The crisis in liquidity necessitated the Government paying £10,000 into friendly societies’ sickness and funeral funds in 1918.41 Servicemen contributing to the Government Superannuation Fund had their status within the fund protected in the War Legislation Amendment Act 1916. The Government was not the only public agency helping to provide for servicemen and their families. Many local authorities also chose to make provision for dependent relatives. Legislative authorisation for this was provided in the War Contributions Validation Act 1914.

Since the 1840s governments had provided pensions for servicemen who had seen active duty, or their widows and dependants. Before the outbreak of war in 1914 there were already 568 pensions being paid for service in the New Zealand wars of the 1860s and the South African war of 1899–1902. The War Pensions Act 1915 provided pensions to World War I veterans or their families, even those who had not seen active service overseas.42 In 1921 pensions were being paid to 31,764 soldiers, widows or dependants, the average annual pension amounting to £55 per recipient. This sum was nearly as much as the average widow’s benefit at the time, and substantially more than the £37 being paid to old-age pensioners.

Miners incapacitated by phthisis, to whom Massey’s Government extended pensions in 1915, received higher payments, at an average of more than £62 pa. These pensions, however, stood apart from others being paid. A fund set up in 1911 into which mine owners contributed collapsed with the virtual cessation of gold-mining at the outbreak of war. Unless the Government took over responsibility for the pensioners their benefits would cease. With an ill grace, Massey’s Government took charge of the pensions. It was, as J. T. Paul noted during debates on the issue, the first occasion when the taxpayer assumed responsibility for compensation for an occupational disease.43

The notion that the State owed much to its servicemen had some similarities to the earlier obligations felt towards settlers. It underlay other efforts on behalf of returned soldiers. The aim of the Repatriation Boards established in 1918 was ‘to secure for [every discharged soldier] a position in the community at least as good as that relinquished by him when he joined the colours’.44 Such goals for returned men were not new. In 1903 Seddon’s Government settled 36 Boer War veterans on farms around Te Kuiti.45 In the Discharged Soldiers Settlement Act passed in October 1915 the Crown took the power to set aside Crown land for soldiers. A sum of £50,000 was provided to help soldiers settle. Terms of occupancy of the land were more generous to servicemen than what was currently available from the State Advances Office. The Act was extended in 1917; the Crown could now purchase private land on the open market and appropriate money to help with housing. Eventually 10,500 men took the opportunity to settle on farm land; another 12,000 were helped to purchase urban sections and to build, or purchase existing homes. Inevitably there were some servicemen who found employment hard to come by. Small ‘Unemployment Sustenance Allowances’ were paid to 188 men during the recession of 1921-22, and several training schemes for disabled soldiers were also set up. An average payment of £55 per trainee was spent on training and sustenance.46

Many returned soldiers gained access to land that might otherwise have been beyond their means. However, the Crown’s active purchasing policy helped inflate land prices in the later stages of the war. Some soldiers who bought privately with government assistance paid high prices and suffered the highest failure rates when commodity and land prices collapsed in the early 1920s. As Ashley Gould has shown, all soldier settlers ‘became dependent upon the financial assistance of the government’. When soldiers got into financial trouble the Crown foreclosed only as a matter of last resort. The number of failures compares well with those of farmers in general during the years to 1935. Yet, the soldier settlement scheme suffered a poor reputation. This had more to do, it seems, with soldiers’ unreal expectations than any intrinsic fault in Massey’s scheme, or the way it was administered. The political promise of ‘a home fit for heroes’ had been over-sold, and was impossible to deliver.47

The influenza epidemic in the last months of 1918 has been described as ‘New Zealand’s worst recorded natural disaster’. A total of 8500 people lost their lives. The death rates were at their highest among Maori, especially in the King Country, where there was as yet no hospital, and in the crowded inner-city suburbs of Auckland and Wellington. Massey later estimated the monetary cost of the epidemic in extra health services at £194,000.48 Coming at the tail end of the war and affecting many servicemen returning from the front, this domestic emergency called for a government response in keeping with the efforts made on behalf of soldiers. Since many parents with dependants were swept away by the ‘plague’, the Cabinet, without statutory authority, decided to build on to its existing pension structure what came to be known as Epidemic Allowances. Paid out initially by local hospital boards but passed back to the Pensions Department for administrative purposes in 1920, a total of 939 were paid that year. Most recipients were widows, although 89 widowers also qualified. The average pension was a comparatively generous £83 pa. The number of Epidemic Allowances fell quickly in the 1920s as children reached an age where they were expected to fend for themselves. The last allowance was paid in 1938.49 Nonetheless, a precedent had been established that would be recalled in later years.

The epidemic placed a strain on health services. This gave rise to an interesting public debate about the extent to which local or central authorities should be responsible for health care. The expanding role of the Department of Public Health and its powers in relation to local government were specially controversial. Departmental officers had been pushing for a more centralised health service before war broke out, and in 1915 they persuaded the Government to take the legislative power to declare some housing unfit for human habitation.50 Departmental officers believed they needed even more powers at the expense of local authorities. They used the epidemic to advance such arguments. Some local authorities fed the move to centralise health services by arguing that the department should be doing more and asserting that it had been ‘caught napping’ with the epidemic.51 When a Royal Commission sat early in 1919 to examine the causes of the plague and the steps necessary to prevent a recurrence, an opinionated departmental officer, Dr Robert Makgill, criticised the legislative status of the department and of existing hospital boards, arguing that this had limited the department’s effectiveness during the epidemic. He recommended passage of new health legislation to strengthen the department’s role.

Such statements provoked an angry retort from the Minister of Public Health, G. W. Russell. In a detailed statement to the commission Russell outlined the more traditional government concept of the relationship between central and local government in matters pertaining to health.

It is not the policy of this or any Government to take away from the functions of city councils and other local bodies, but rather to enlarge those functions and to employ the Public Health Department as far as possible as an advisory and supervising authority…. The idea of the Public Health Department assuming anything more than supervising authority and powers of direction regarding sanitation, drainage etc., would be too ridiculous for words…. The people of New Zealand would never for one moment tolerate the establishment of a bureaucratic system as regards health or any other subject.52

Russell’s was a minimalist approach to government. By this time it commanded less public support than in the Liberals’ heyday. An MP of seventeen years’ standing, Russell lost his seat at the election in December 1919.

Makgill’s centralist philosophy continued to be heard. It strongly influenced the Health Act of 1920, which, in Geoffrey Rice’s words, ‘radically restructured New Zealand’s public health administration’. The Act created seven separate divisions within the department with responsibility for public hygiene, hospitals, nursing, school hygiene, dental hygiene, child welfare and Maori hygiene. While local authorities were still expected to contribute to the cost of their hospitals, central control advanced substantially. The Chief Health Officer was henceforth designated the Director-General of Health, ruling over a department which grew steadily more powerful over the years ahead.53

Financing public hospitals bedevilled governments for the rest of the century. Under the Hospitals and Charitable Institutions Act 1909 local boards were expected to raise 50 per cent of the running costs of the hospitals in their districts. Local authorities were obliged to contribute. However, raising the local component of hospital costs by way of rates, especially in low income areas, was always difficult. Successive amendments to the legislation gave the Government the power to advance money to hospitals in anticipation of rating income, and the formula for calculating subsidies was constantly rejigged, usually at the urging of harassed chairmen of local boards. Boards resorted to some ingenious methods to milk government subsidies, especially those that had traditionally been paid on gifts and bequests. In December 1920 an Audit Office inspector perused the books of the West Coast boards. He reported: ‘ am as a child in the hands of the West Coast Boards when it comes to claiming subsidies. Recently the Grey Board received a donation of a truck of coal and they point out to me that by drawing a cheque on it and receiving it back they are able to get 24/- in the £ on its presumable value, and I do not see that I can stop them.’54 Eighteen months later the West Coast boards, which were always on the lookout for gifts that might qualify for subsidies, received a donation of money from the Kumara Racing Club. It seems clear that it was money that ought to have been paid to the club’s creditors.55

Hospital boards with uncertain income flows from local authorities had difficulty budgeting. The Government experienced the same problem, especially since the amount of money required to subsidise gifts and bequests could never be accurately predicted. The more that central government insisted on localities paying their hospital dues and enforced penalties on those that fell behind, the angrier local boards became. A testy bunch of chairmen complained to Massey in July 1923 that government subsidies which purported to be 50 per cent of the total running costs had fallen to 42 per cent. The Government responded by amending the Act and providing relief for boards such as those in the Far North where it was proving difficult to collect rates levied on Maori-owned land. At the same time, other boards in wealthier areas such as Tauranga received substantial bequests that qualified for subsidies, resulting in the construction of facilities not enjoyed elsewhere, and for which further government maintenance subsidies now became payable.

During the 1920s subsidies to hospital boards rose at a much faster rate than inflation. In September 1927 Treasury’s Chief Inspector, Bernard Ashwin, had some trenchant comments to make about the system:

The Hospital Boards have at present not much inducement to exercise economy. Their rates are collected for them by the City Councils and other Local Bodies, and these Bodies receive all the odium that accrues from the collection of rates, although they merely act as agent in the matter. In the second place, subsidies from the Consolidated Fund are paid practically automatically. Further, it seems likely that in many cases the receipt of voluntary contributions and bequests (and particularly the latter) instead of relieving the charge on the ratepayer and the taxpayer merely increase their burdens. For instance, large bequests plus the State subsidy thereon are often used to erect additional buildings that are really not needed and would not otherwise have been erected. The State bears half the cost of the capital extravagance, and thereafter the State and the ratepayers have to share the cost of maintenance.56

Regional disparities in hospital facilities that remain a problem today began showing up in the 1920s. The Government had not set out to help more affluent areas, but this was an unintended consequence of their incremental subsidy system.

The rigours of World War I impacted in other ways on the relationship between the New Zealand people and their government. The popular demand for ‘equality of sacrifice’ was one factor in the introduction of conscription in 1916. More important, as Paul Baker has shown, was an urge for social control that was at its most fierce among the growing Protestant middle class. Industrial unrest, a perceptible rise in the number of Irish immigrants, working class ‘idleness’, drunkenness, prostitution and declining church attendance created the urge for more social discipline and efficiency.57 In the years between 1909 and 1914 compulsory military training for young men became the norm. Dr Truby King enlisted political support – and in 1921, financial help as well – for his Plunket system of baby care which aimed at improving ‘the health of the family, the nation, and the Empire’.58

The temperance movement, which had been growing for many years, came into its own during the war. Richard Newman has shown that the drive behind demands for prohibition that won the support of 55.8 per cent of the voters in a poll on 7 December 1911 was strongest in prosperous middle-class areas. The same people urged Massey to reduce drinking hours in two large parliamentary petitions presented in 1915 and 1916. Eventually on the recommendation of a self-important group of businessmen whom Massey appointed to a National Efficiency Board, the Government banned ‘shouting’ or ‘treating’ in hotels. In 1917 hotels were obliged to close at 6 pm. Consuming liquor in restaurants at any time when hotel bars were closed became an offence, while serving alcohol with meals in hotels after 8 pm was also outlawed.59 Jock Phillips observes that by these actions, ‘barricades had been erected to contain the drinking culture, and an uneasy peace prevailed virtually unchanged for the next 50 years’. Many of these prohibitions, some of them unenforceable, lasted until the liquor laws were partially relaxed in 1960. A Special Licensing Poll on liquor took place on 10 April 1919. Only a huge majority for continuance from returning servicemen saved New Zealand from prohibition.60

Other areas of personal life were the subject of legislative intrusion. In the Prisoners’ Detention Act 1915 and the Social Hygiene Act 1917 the Government armed itself with greater powers to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases,61 while the Cinematograph-film Censorship Act 1916 made it unlawful to exhibit any film unless it had been approved by a censor. The Act stipulated that ‘Such approval shall not be given in the case of any film which, in the opinion of the censor, depicts any matter that is against public order and decency, or the exhibition of which for any reason is, in the opinion of the censor, undesirable in the public interest’. In the War Legislation Amendment Act 1916 it became an offence punishable by a fine to use any word with reference to the war that ‘may be offensive to public sentiment’.62

Massey’s National Efficiency Board established in February 1917 was given a wide brief to review the economy in general, to inquire into industrial efficiency, and to recommend such measures as it thought necessary to reduce the cost of living, promote thrift and deter luxury. Chaired by William Ferguson, this unpaid group of Government supporters produced a lengthy report with a distinctly Calvinist bias. They recommended that the number of race days should be reduced, that there should be no new permits for picture theatres, and there should be less ‘waste’ on imported luxuries such as cars. With a zeal that would have inspired today’s anti-smoking lobbyists, they recommended that bread should be at least twelve hours old before it was sold because stale bread was ‘healthier’ than fresh bread. Moreover, bakers would not need to begin work so early in the morning. The Board went too far for Massey’s Liberal colleagues; in his 1917 budget Ward specifically knocked back those suggestions that might reduce the Government’s Customs revenue.63 But there could be no denying that there was an appetite for a socially active state among many of the country’s more affluent citizens, especially those who were too old to fight, but who wanted to use the occasion of war to circumscribe the pleasures of the young.

Peace celebrations in Nelson, 19 July 1919. Nelson Provincial Museum

By the end of the war there were two new forces pushing inter-ventionism. The first was the Returned Servicemen’s Association. Its initial conference in Christchurch in May 1919 was alive with demands for more government action on behalf of returned soldiers. Higher allowances, better hospital facilities, and more ‘courageous’ treatment of venereal disease were just some of the topics discussed.64 Ministers quickly learned the wisdom of attending annual conferences and listening intently to the R.S.A.’s pleadings.

An even more effective advocate of centralisation – since it involved itself directly in the political process – was the New Zealand Labour Party. Throughout the 1920s the Liberal and Reform parties manoeuvred carefully around this rising political force. Products of rapid urbanisation and a flourishing trade union culture that was partly encouraged by the I.C.&A. Act,65 several political labour leagues emerged after 1905. They were determined to gain parliamentary representation for working men and women. David McLaren, secretary of the Wellington Waterside Workers’ Union, was their first success when he won the seat of Wellington East in the election of 1908, courtesy of the short-lived second-ballot procedure.66 The second ballot helped four Labour MPs into Parliament in 1911, and two more followed in by-elections in 1913. During the war six Labour or Social Democratic MPs under the leadership of Australian-born Wellington lawyer, Alfred Hindmarsh, constituted an unofficial opposition to the National Government. In July 1916 the various labour groupings united to form the New Zealand Labour Party. In 1918 three by-election victories added further strength to Labour’s team.67

The ideological ingredients that went into the Labour Party’s emerging philosophy were many and varied.68 Harry Holland, who succeeded Hindmarsh as leader, was an eclectic reader whose background as a journalist kept him with pen in hand for most of his life. He produced many pamphlets. Steeped in unionist theory and socialist thought, he had edited the International Socialist Review in Sydney before coming in 1912 to New Zealand, where he soon became editor of Labour’s Maoriland Worker. He held the position for five years before entering Parliament in May 1918 as MP for Grey.69 Holland’s chief strategic goal was to force the Liberal and Reform parties to merge, thus clearing the way for the Labour Party to establish a constituency with working people. Along with several other Australians such as Michael Joseph Savage, Robert Semple and Bill Parry, a Scotsman, Peter Fraser, and an Irishman, James McCombs, Holland helped to further the cause of socialism that had been developing under the wing of the ‘Red Feds’ since 1908.70

Central to Labour’s philosophy was a belief in the essential benevolence of public activity and the need for government controls over private enterprise. Hindmarsh declared in his maiden speech that he favoured an extension of the functions of the State, and that they should be administered in a ‘just, honest and straightforward’ manner.71 In one of his early speeches Peter Fraser, who won the Wellington Central by-election in October 1918, denounced private ownership of rental housing as ‘a complete failure’. He urged the Government to use the labour of returning soldiers to build houses.72 Holland wanted a more active Department of Health and an end to all profiteering. He disliked the War Regulations, labelling them both ineffective and ‘the autocracy of mediocrity’. In a bold declaration of Labour’s philosophy, Holland told Parliament:

We do not come merely to attempt to make a change to individuals on the Government benches. We of the Labour Party come to endeavour to effect a change of classes at the fountain of power. We come proclaiming boldly and fearlessly the Socialist objective of the Labour movement throughout New Zealand; and we make no secret of the fact that we seek to rebuild society on a basis in which work and not wealth will be the measure of a man’s worth…. We shall often shock the unthinking members of this House, and … often infuriate the intolerant members. But one thing is certain: we shall in the end succeed in converting the intelligent section.73

After he entered Parliament in 1919 Savage interested himself in finance, and argued for a state bank. In his maiden speech he attacked overseas borrowing, declaring that he did not wish to borrow anywhere. ‘I do not want to give the Bank of New Zealand, the National Bank, or any other bank the right to use the public credit for private gain. I would sooner have a State bank, and use the public credit for the public good.’74 These were the early days of a movement that succeeded after a lengthy apprenticeship during the 1920s, and considerable refinement of theory, in establishing hegemony over New Zealand’s workers. Labour was to preach a philosophy of state intervention for the rest of the century.

By 1919 both the Liberal and Reform parties feared Labour. Before the election Massey conducted a scare campaign against it, portraying Labour’s leading figures as Bolsheviks; his deputy, Sir James Allen, claimed that Holland was ‘vindictive, disloyal, and a reveller in filth’.75 Ward’s Liberals adopted a radical manifesto for the election in the hope of outbidding Labour’s appeal to workers.76 It did them no good. Their seats fell from 33 to 19, and Ward lost Awarua, which he had held for 33 years. On 17 December 1919 Labour benefited from working-class hostility to rising prices and perceived profiteering, and nearly trebled the votes received by Labour groups in 1914. With almost 24 per cent of the national vote and a total of eight seats it was now a force to be reckoned with.

Over the longer term, Massey’s Government tried countering Labour’s growing appeal with further state intervention. In March 1920 the Prime Minister restructured his ministry, promoting to Minister of Public Works the war hero, Gordon Coates, who was known for his activist approach to government. Coates soon pushed ahead with road and rail construction and with electricity production.77 Massey’s budget of 27 July 1920 hinted at further government activity on many other fronts. Yet, at the end of an activist statement he ended with the words: ‘The happiness and prosperity of the people … can best be secured by furthering the spirit of self-reliance, industry, and thrift which has been characteristic of our people …’.78 Massey was revealing the degree of philosophical schizophrenia that lay behind his Government’s policies. Claiming always to believe in private enterprise, his administration had become the most interventionist in New Zealand’s history. In later years while the gospel of self-help marched hand in hand with state initiatives, it was invariably half a step behind.

Whatever Massey’s intentions in the middle of 1920, the collapse of export prices towards the end of the year forced his Government to retrench. On 17 December he instructed his ministers to tell their departments to reduce spending ‘as much as possible, having due regard to efficiency’. Any new expenditure had to be checked first with Treasury. In April 1921 a Government Service Commission was established to review public expenditure.79 Top of its list of items for review was the now bloated public service. The number of employees had grown during the war and, after the introduction of minimum salaries for civil servants in June 1914, the cost of the bureaucracy rose steadily.80 Sloppy work habits in the public service became a topic of adverse press comment in 1918.81 In 1921 every department was requested to present the commission with a list of economies. Most suggestions minimised staff layoffs, relying instead on what came to be known in later years as ‘the sinking lid’; employees who died or retired would not be replaced. Wages and salaries were cut back by between 7 and 10 per cent, and the bulk of employees in the Public Works Department were reclassified as relief workers. Railways made 105 men redundant. The total number of public servants declined until 1924 when they began inexorably to rise again. The Arbitration Court also reduced the basic wage by five shillings per week. Despite these moves the Government was obliged to use some of its accumulated wartime surpluses to balance its budgets.82

Farmers and stock and station agents became gravely apprehensive about the unprecedentedly steep drop in New Zealand’s earnings overseas in 1920.83 In the financial year 1920-21 New Zealand’s imports cost £67.4 million, while exports brought in only £48.2 million. It was the largest deficit in overseas trade in New Zealand’s history to date. While Massey was overseas for some months in 1921 the Government moved slowly. However, the emergence of a Country Party in rural areas galvanised the Prime Minister into action on his return. The new party was arguing for credit reform, mortgage interest reductions, a state shipping line and state marketing of exports. The limitations on mortgagees’ rights were revived, and on 19 December 1921 Massey announced that he was beginning discussions with producers’ organisations with a view to taking over the export of all meat.84 Despite criticism from exporting firms with a stake in the status quo, the Meat-export Control Act passed through Parliament on 11 February 1922. It was described as ‘an Act to make provision for the appointment of a meat producers’ board with power to control the meat-export trade’. A lengthy preamble described the current crisis and concluded that there was a need for a board ‘with power to act as the agent of the producers in respect of the preparation, storage and shipment of meat and its disposal beyond New Zealand’. To a point, the legislation was permissive; a board consisting of two government nominees plus five elected by producers was given the discretion to adopt absolute or limited control over meat exports. But whichever option was chosen, meat producers could be levied in order to pay for the board’s costs. In the meantime, the Minister of Finance was empowered to advance money to the board for operating costs. The board was deemed to be the agent of the owners of the meat.85

This was the first of what became a raft of export boards with their own acts of Parliament. The activities of the Meat Board bore some resemblance to the recent war-time commandeer; farmers were paid for their produce while a more distant authority, albeit theoretically under their control, accepted the responsibility for shipping and on-selling, principally in London.

Massey gave a rambling speech in justification of the Bill when he moved its second reading in February 1922. He argued that ‘the setting-up and bringing into operation of a pool, controlled partly by the Government, partly by the producers’ representatives and partly, probably, by commercial men, will be the best safeguard we could possibly have, because it will be their business to prevent any wrong doing in connection with the export of our produce’. The Labour Party declared itself in favour of ‘State marketing’ but felt the legislation fell short of the ideal. According to Holland, the Bill ‘reads something like a species of high-brow syndicalism. It certainly does amount to a private profiteering department of industry having the whole credit of the State behind it.’ Yet while the State accepted responsibility for the marketing of meat, in his opinion it lacked effective control.86 This line of criticism from the left would be repeated in future as further planks of the welfare state were put in place and the roles of producers, workers, ‘middlemen’ and the State became entwined.

Not to be outdone by meat producers, many dairymen lobbied for the same system. For many years the National Dairy Association had been discussing what it saw as the need for cooperative marketing of dairy produce. Leaders of the dairy industry watched the work of producer boards in the United States and Scandinavia. In the six years before 1914 there were discussions between North Island butter factories about the advantages of careful control over the shipping to, and selling of produce on the London market.87 In October 1921 the Government began experimenting with drip-feeding supplies of butter on to the London market in the hope that prices would improve. They did not. Instead, the British Government contemplated releasing the last of its war time stockpiles of New Zealand butter to satisfy local demand. Massey had an uncomfortable Christmas while cables flew back and forth to London. New Zealand’s High Commission struggled to avert a catastrophe.88

In March 1922 a Dairy-produce Export Control Bill was introduced. Dairymen quickly revealed what became their identifying characteristic: they were more disputatious than their meat and wool brethren. While a majority always supported the legislation, there were many who regarded the Bill, in the words of one of Massey’s correspondents, as ‘drastic, arbitrary and unjust’.89 Debate raged, fuelled by the propaganda of proprietary companies with an interest in the export of butter. They portrayed Massey’s legislation as state socialism. With an election coming up, Massey decided not to force the issue. The Bill was held over and was not passed until 28 August 1923.90 It was to be brought into force by proclamation only if it received majority support in a referendum of dairy producers – which it eventually got. There were 56,000 dairy producers entitled to vote. Some 24,233 (43.2 per cent) chose not to vote; of those who did vote, 22,284 (39.7 per cent of the total) supported compulsory pooling and selling of butter, while 9255 (16.5 per cent) opposed.91

Further producer boards followed. A Fruit-export Control Act and a Honey-export Control Act were passed in 1924. Together the boards can be seen as a milestone in the development of relations between the Government and private entrepreneurs. With the experience of wartime controls behind them, both had come to the view that better financial outcomes for individuals could be achieved through collective action rather than individual effort. It was a conclusion that other farmers and manufacturers arrived at in the years to come.