The years of almost continuous prosperity from 1895 to 1920 ill prepared New Zealanders for the uncertainties of the 1920s. Export prices fell in 1920, rose again later in the decade, slid, then skyrocketed briefly before plunging to earth after 1929. Nerves rubbed raw by the bitterness of war were soothed in the first half of 1920 when prosperity and progress were on everyone’s lips; they began trembling again during the recession that dominated the next two years. Unease crept back towards the end of 1925 and lingered as unemployment slowly gathered pace in the winter of 1926. Few private companies were now contemplating expansion. Yearning for pre-war certainties intensified, as average wealth, after rising steadily at the end of the war and peaking in 1924, fell away over the following decade.1

The 1920s were the first occasion when government intervention in the economy was seriously questioned. State trading enterprises such as Railways and State Coal Mines began losing money. Some businessmen said that the Government had overreached itself, that it was not capable of being a competent business manager, and that taxes were therefore higher than they needed to be – a point that was disputed by a Royal Commission into taxation in 1924.2 Stronger forces weighed in to support further state activity. The era of government-led expansion, in which railways had played such a key role, was far from exhausted. Considerable faith in the magic of rail remained, especially in the more remote parts of the country that were yet to be linked into the national grid. Governments realised that the appearance of a railways gang in a marginal electorate during the run up to an election was good politics.3 State unions agitated for better working conditions. When depression came and unemployment rose rapidly, workers expected the State to provide jobs, and when services were cut back, they rioted in 1932 with demands for more publicly provided relief. As prosperity eluded many, the New Zealand public valiantly held on to an article of faith: governments could do anything. Having won the war, politicians could easily win the peace and conquer depression. Confidence in what some called ‘scientific’ planning encouraged governments to intervene further. Coming after a long period of uninterrupted prosperity, the 1920s bore similarities to the 1970s and early 1980s. However, by then the State’s apparatus had become top-heavy and was difficult to sustain; confidence in the omnipotent State was declining rapidly.

In December 1922 Massey’s Reform Government faced its toughest election to date. It was finally saved on a parliamentary confidence motion in March 1923 because its opponents could not cooperate. The Government kept a tight rein on expenditure that year and efforts were made to improve the effectiveness of governmental activity. Talk of the need for more ‘business efficiency’ was common; on the eve of the 1925 election Reform borrowed the slogan ‘more business in government; less government in business’ that the Republican Party had nearly pummelled to death in the American presidential election the previous year. Sloganeering disguised a reality of the 1920s; there was more government in business by the end of the decade. Moreover, the rate of intervention stepped up during the depression that followed.

As Minister of Public Works, Gordon Coates played a major role in promoting state activity. In its early days the Reform Government had hoped to involve locals and private companies in railway construction, believing that if communities seriously wanted a new rail line then they would put their money where their mouths were. A Local Railways Act was passed in 1914 which set out the procedures which communities were required to follow. Little happened. Several small company lines were constructed, most of them between three and five miles in length.4 The war intervened, and by the early 1920s state construction predominated. Despite an assertion in 1923 that he would test the efficiency of the PWD’s contracting gangs by letting private contractors build branch railway lines, at no point does Coates seem seriously to have considered contracting out all construction work. On taking office in 1920 he was faced with a huge backlog of projects. Most public works had been suspended for the duration of the war, with only the Otira tunnel continuing at normal speed. Many of the stalled projects were rail links that had been promised at earlier elections. As Vogel had discovered half a century earlier, only the State seemed to be in a position to achieve quick results.5

Coates found himself subject to conflicting pressures. In the early 1920s it was impossible to ignore demands for more and better roads. By then there were more than 20,000 cars in New Zealand, and the number increased rapidly during the 1920s. Railways, the State’s biggest trading department, earned the most revenue ever in 1920-21, but from then on passenger numbers slid because of competition from cars and buses. Work on roads was beginning to cancel out profits from rail.6

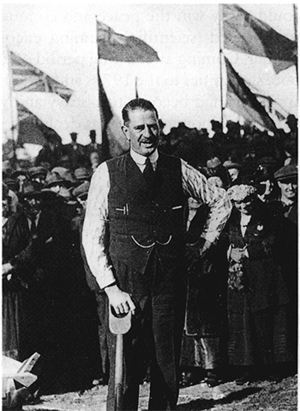

The activist Gordon Coates, Minister of Public Works 1920–25, Prime Minister 1925–28 and Minister of Finance during the depression’s darkest days, 1933–35. Evening Post

The story of how Coates slowed some railway lines, purchased new equipment, and concentrated on completing three main trunk lines, has been told elsewhere. Likewise, his moves to centralise main roads construction.7 However, despite the Government’s efforts to cut back on wasteful duplication and a peremptory knockback to the railway unions when they went on strike in April 1924, the construction and running costs of Railways continued to escalate. When Massey added the Railways portfolio to Coates’s Public Works responsibilities in 1923, the minister was faced with a conundrum. On the one hand, Railway profits were sliding; on the other, the Government increasingly used Railways to mop up pockets of unemployment. The unions pushed for shorter hours, better superannuation, and more Railway houses. The minister tightened administrative procedures and searched for ways other than staff layoffs to reduce costs. He tried to avoid constructing lines likely to prove uneconomic.8 But the intractable financial problem was the steady rise in staff; wages constituted 70 per cent of total expenditure. In 1918-19 Railways employed 12,391; in 1924-25 this number had risen to 16,353 and by 1929-30 there were 19,410 on the payroll. By this time nearly 5000 were casual workers. The key factor in keeping work contracts mostly ‘in house’ was almost certainly the Government’s desire to retain an employment agency close at hand at difficult moments. It proved to be an expensive exercise. The average cost of constructing lines in 1930 was £35,000 per mile; estimates for new work were nearly always exceeded. The State was unable to prevent cost overruns.9

Ward’s assurances in 1906 that Railways would return 3 per cent on capital did not take into account the interest on the money that was constantly being borrowed to develop new lines. On the one hand, Coates boldly asserted in 1923 that Railways ‘have never been regarded … as a profit-making concern’, and he doubted whether the public would approve of them being ‘guided solely by considerations of financial return’; on the other hand, he was also pledged to ‘business-like’ methods, and it had never been envisaged that publicly owned transport services would become a burden on the taxpayer. Comments from journals such as the New Zealand National Review to the effect that Railways lacked business acumen stung Coates.10 He agreed to the restructuring of Railways’ accounts from 1 April 1925. Interest charges of 4.125 per cent (subsequently 5 per cent) were included on accumulated borrowings which then totalled £50 million. Operating returns immediately sank below target. Notwithstanding this, the department continued to take on more staff in 1926 and kept scheduling services that were poorly patronised. In 1926-27 Railways’ gross revenue fell while costs continued to rise. The Government had no option but to pay a subsidy of £445,000 to keep branch lines operational; a further £193,000 went into various Railway superannuation arrangements.11 The following year ministers agreed to reduce freight rates as part of a programme to encourage New Zealand production. This move further reduced Railways’ income.12 Not only was the State now openly in breach of its guidelines for operating public utilities; it seemed also to be losing control of its accounts. The Minister of Finance, William Downie Stewart, kept preaching the virtues of balanced budgets. Yet, if more and more subsidies had to be paid, balancing the budget could be achieved only by higher taxation. Moreover, continued borrowing was needed to maintain progress on an assortment of government construction schemes in order to justify keeping so many people on the State’s payroll. All this was required at a time when earnings from exports were trending downwards and the Government’s revenue was far from buoyant.

In 1928 a number of senior public servants as well as the press began grappling with Railways’ dilemma. Coates, who was both Prime Minister and Minister of Railways by this time, sought the advice of his most trusted adviser, F. W. Furkert, who was Under-Secretary of the Public Works Department and Chairman of the Main Highways Board. Much of Furkert’s professional career had been devoted to railway construction dating back to the days of the Midland Railway. He wrestled with Railways’ predicament and reported in May 1928 that due to competition from roads, railways might no longer be worth the money invested in them. Instead of questioning the indisputable fact that Railways had become an employment agency as much as a transport service, Furkert suggested that road users, who were regarded as responsible for the problems of rail, ought to bear the cost. In effect he was arguing for a tax on motor fuel to support a mode of transport that the public was deserting. And since Railways were being used for the social purpose of minimising unemployment, their accounts should be topped up from the Consolidated Fund.13

A few weeks later a Dominion editorial supported Furkert’s suggestions; it hoped, naively, that state subsidies would not distort the transport market or impact unfairly on private enterprise. Treasury endorsed Furkert’s suggestion of a motor fuel tax, but opposed government subsidies.14 Yet, in 1930 Railways required a government subsidy of approximately £1.2 million a year to keep functioning. Accumulated losses during the previous five years totalled £2 million.15

Furkert’s ideas led in time to a raft of measures designed to protect Railways, ostensibly to safeguard the public’s investment in their construction, but in reality to hide the fact that the department’s core business had become as much concerned with welfare as transport. Large operational subsidies became a recurring feature of Railways’ accounts in later years, and this trend was interrupted only briefly by the efforts of the Government Railways Board that managed Railways between 1931 and 1936.16 Given the increasing competition that railways were encountering, the 1930 Royal Commission on Railways argued that they deserved protection. The Transport Licensing Act in November 1931 gave the Government wide powers to issue orders-in-council establishing licensing districts and to control the means by which goods were transported within these districts. A limit of 30 miles was soon imposed beyond which road transport was prohibited from carrying goods. When this monopoly provision proved to be no cure-all, the limit was extended in 1961 and again in 1977, when it was fixed at 150 kilometres. This monopoly for Railways was not lifted until passage of the Transport Amendment Bill (No.5) 1983, by which time restrictions on the cartage of goods by road were vigorously opposed by private enterprise and had long been flouted by trucking firms, with the connivance of producers.17

A wish to protect the Government’s investment in Railways was the reason given for moves in the late 1920s to have Railways enter into direct competition with private bus transport. In November 1926 Railways bought an old bus fleet that was providing a service from Napier to Hastings. Over the next two years there were further purchases in the Hutt Valley, in Christchurch and in Oamaru. But these services, too, lost money, adding to the overall Railways debt.18 Yet Railway Road Services expanded over the years, continuing into the 1980s. It rarely declared a profit.

In 1929 the Government hoped to ease Railways’ burden in another way: it wrote off £8.1 million from the sum on which Railways had to pay interest. In 1931 a further £10.4 million was written off.19 But there were still no operating surpluses when remaining debts were included in the accounts. Treasury pushed for a variety of fare rises, arguing that rail journeys ‘belong to a class of State activity in which the principle of user pays should apply’.20 This argument was vigorously supported by Professor B. E. Murphy of Victoria University College.21 In reality, competition with road and the obligations on Railways to operate as an employment agency and provide subsidised housing for employees working outside the main centres were putting impossible burdens on operating costs.

Electricity generation was similarly brought under the State’s wing after World War I.22 Electricity was first produced in New Zealand for public use in 1887. By 1898 local authorities were producing it. Following advice from American experts in 1902, central government took the exclusive right under the Water Power Act 1903 to generate electricity using water, although this right could be – and sometimes was – delegated to a local authority, and after 1908 to private companies as well.23 The process of government involvement was taken a step further in the Water Power Works Act 1910, when the Government gained authorisation to raise money to construct hydro-electric stations.24 Work soon began at Lake Coleridge, where construction was completed in 1915. By this time electricity was also being produced in the Hutt Valley and at Waipori.

As with early railway construction, the State had taken the lead because there was insufficient interest being shown by private enterprise in developing a vital utility. Again there was debate in Parliament over whether the State should be encouraging private enterprise, or whether it ought to take the dominant role itself. The consensus that emerged was that in a small country like New Zealand, the desirability of preventing a private monopoly required an active State. Parliamentarians warmly endorsed government involvement. In the Legislative Council C. M. Luke declared: ‘I believe the success of many of the enterprises the Government has undertaken in the past in the direction of encouraging the production of this country speaks eloquently for the administration of the country’. John Rigg hoped that electricity would be a major money-spinner for the Government: ‘It should … be the duty of the State on entering upon a great enterprise of this kind to see that it returns a fair profit to the State on the investment, and that the whole benefit to be derived from it should not go to those who are consuming the power which is supplied by the Government.’25 Rigg was reflecting a view that was gaining currency – the Government’s role was both to generate and to redistribute wealth.

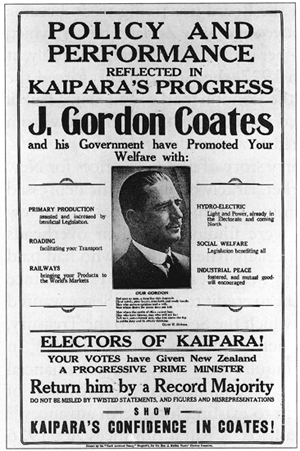

In the absence of significant private interest, the State became involved in power production; Massey officially opens the Mangahao Power Station, November 1924. ATL G-8607-1/1

While the Government granted occasional licences to private companies to develop power, such licences were controlled carefully. In addition to local authority plants, many of them using coal, there was a small network of private producers in existence by the end of the war.26 However, it was soon clear that only the Government could command the finance necessary to proceed with the grand plans produced in 1918 by Evan Parry, the Government’s Chief Electrical Engineer. Parry envisaged a rapid increase in production as well as reticulation of the whole North Island.27 Coates pointedly stated in July 1921 when announcing plans to construct three major hydro stations in the north: ‘The Government’s margin of credit and security is immeasurably greater than that of any local effort’. He added that in his view local authorities were most unlikely to be able to provide electricity as cheaply as the State.28

A few private entrepreneurs continued with thermal explorations in the hope of finding an economically viable alternative source of electricity but there were so many regulations to comply with after 1934 that most gave up. Private companies wishing to compete with the State’s hydro network had effectively been squeezed out by the 1940s.29 Electricity production became a huge state activity. Construction workers numbered 3993 in 1920. They topped 10,800 a decade later when the pressure was on to complete the difficult Arapuni dam on the Waikato River. Numbers fell back during World War II but rose again as new stations were completed in the late 1940s and 1950s.30

Once Coates had headed off the State’s competitors in electricity production, efforts were soon underway to construct a national distribution grid. Getting details from local authorities and companies about existing grids was not easy.31 However, by 1926 38 publicly elected power boards were using the Electric Power Boards Act 1925 to borrow, and were hard at work reticulating electricity to the nation’s homes. In 1985 it was estimated that $5.6 billion had been spent generating, transmitting and distributing electricity throughout the country. Of that amount, more than 71 per cent had been raised and spent by central government; the rest was the responsibility of power boards.32 As with the construction of railways, public authority once more triumphed over private intitiative. However, in the case of electricity, public demand never flagged. It was only the introduction of politically driven pricing policies in the middle of the century that ever adversely affected the profitability and social usefulness of this public utility.33

By the early 1920s State Mines was twenty years old. Like Railways, it still produced surpluses although it no longer paid interest on all money borrowed because some had been written off in 1913. Trading surpluses were not always invested profitably. On 19 December 1919 the Treasury’s accountant checking the books of State Mines noted that the surpluses were ‘idle’: ‘As this is a commercial department it should be run on practical business lines, and where there is an opening for investing advantage should be taken of the opportunity.’34 Treasury, it seems, had been pocketing the interest on the trading surplus rather than crediting it to the Mines Department. Burnt in earlier years by the over-capitalisation of State Mines, Treasury was keeping the department on short pay and rations.

State Mines always needed capital for expansion but was powerless to raise loans without permission from Cabinet. It was expected to operate commercially, yet it never enjoyed the autonomy of private enterprise. There is no indication that either Treasury officials or ministers ever questioned whether there was still a need – if indeed there ever had been – for the State to be owning and operating mines. In the uncertain 1920s the Government was beginning to reap the consequences of its huge capital investment in railways and mines, and the unbusinesslike management of these enterprises. The situation at State Mines deteriorated during the depression when demand for coal subsided. By then all state trading agencies had become employment agencies. Trading surpluses declined. Several city coal depots showed trading losses and were eventually closed. State Forests, too, operated at a loss throughout the depression, largely because it was expected to carry up to 848 relief workers planting exotic trees.35

While central government increased its infrastructural investments during Massey’s later years, the State also edged forward in social policy areas. Although the Board of Trade went into hibernation in 1924 the power to regulate prices remained in force under the 1919 legislation. Bread was still controlled. Other regulations were gazetted from time to time. The 1924 Gas Regulations required that supplies be made available at specific calorific levels and at reasonable prices. The Tailoring Trade Regulations stipulated that all articles of clothing that claimed to be handmade had to contain a specified amount of hand work.36

Massey’s Government accepted more responsibility for housing. Lending under the Advances to Workers scheme continued, and there was a steady rise in the number of government loans to local authorities for rental house construction as ministers strove to persuade councils to accept social responsibilities. Railway workers and State Coal miners were housed at subsidised rents. In the hope of controlling urban house rents the Government retained its wartime rent controls. Each year the legislation fixing rents at the level of 3 August 1914 was extended in a series of Rent Restriction Acts. Unions and the Labour Party set store by controlling rents, many arguing for controls in other areas as well.37 But as the years went by Massey had cause to doubt the wisdom of government involvement in rent controls. In his budget of 1923 he claimed that the Government was doing a lot to help house families, but declared testily: ‘It should not … be expected of the State alone to provide the means of meeting the [shortage of housing], and the housing problem will not be solved until private capital is more extensively employed than has been the case in the immediate past.’38

Two problems were becoming apparent with rent controls. In the first place, many private investors who owned rental accommodation in 1914 and who found their rents frozen, despite several years of steep inflation, were disposing of houses and investing elsewhere. This reduced the stock of rental housing.39 By 1924 only a relatively small number of rental houses with controlled rents still existed. Secondly, landlords who built or bought untenanted houses after 1914 were not covered by the controls. Some workers who were lucky enough still to rent a house with a controlled rent were paying as little as £1 per week in rent; others with non-controlled rentals were paying as much as £4 per week. The Act was amended in 1924 to bring more houses under the umbrella of the controls. A ‘standard rent’ could be defined as 8 per cent of the capital value of a house, and could be fixed by a magistrate.40

This move did not solve the problem. Investors again edged away from rental properties. In August 1926 when the Rent Restriction Act was extended once more (the ritual continued until Labour passed the Fair Rents Act in 1936), Legislative Councillors roundly criticised the move, pointing out that rent restrictions had played a major part in creating a housing shortage rather than solving it. Rents were high because the legislation had resulted in a reduction of stock, thus pushing up rents for those houses remaining in the rental pool. A. S. Malcolm, a teacher, sportsman and land agent from Balclutha, commented, ‘I can understand how difficult it is to get out of a bog such as this once we have entered into it. I do not think any country can venture to interfere with the law of supply and demand as we have done and keep it up continuously without great injury to the public’ Malcolm concluded that the Government’s desire to help tenants ‘ran in front of their judgement’.41 Advocates of rent control refused to heed such judgements for another half century, hoping always that further refinements to the control mechanisms would result in an adequate supply of houses at low rents. Rent controls remained in force with diminishing effectiveness until 1985.

Meantime, Massey’s Government was also putting more money into education. The number of teacher trainees rose steadily after the war, and more than kept pace with the primary school children who received the ‘free, compulsory and secular’ education provided by Education Boards. Attendance at the 130 Native Schools also rose and in 1923 the Education Department established a new category of schools known as Junior High Schools, later called Intermediates. Free places at secondary schools increased, as did the number of national scholarships.42 In the Education Amendment Act 1924 all teachers were required to register, and the following year Education Boards were given wider powers to prevent overcrowding in schools.43 In 1925 a Child Welfare Act was passed. It created a special branch of the Education Department known as the Child Welfare Branch, which was to look after children who were under the protection of the State and to provide for the education of indigent, neglected or delinquent children.44

A state-provided school bus – with a puncture, 1924. Wagener Museum

There were changes, too, to the rules governing pensions. The restrictions limiting their availability were relaxed in 1924; widows could earn more before their benefits were abated. A new class of benefit, Blind Pensions, was also introduced. In this area as in so many others the Reform Government was carrying on the policies of its predecessor.45

It was noticeable that the same urge for social control that had come to the fore during the war continued into peacetime. In the Education Amendment Act 1921-22, all teachers, whether they were in public or private schools, were required to take an oath of allegiance. In 1924 an amendment to the Police Offences Act prohibited retailing on Sundays, although an exemption was provided for bookstalls at railway stations. The rules regarding rogues and vagabonds were tightened and it became mandatory for there to be supervision of wrestling contests. The publication of unauthorised programmes for these contests was also outlawed.46 In the same year a Masseurs Registration Amendment Act passed Parliament because legislators professed to be worried about the lax definition of what constituted a massage, and the extent to which sexual services were provided by some masseurs. Clause 2 of the Act tortuously defined a massage as:

use by external application to the human body of manipulation, remedial exercises, electricity, heat, or light, for the purpose of alleviating any abnormal condition of the body, or the use for such purpose of any other method of treatment that may be recognised by the Governor General in Council as an approved method of performing massage, but does not include the internal use of any drug or medicine or the application of such appliance except so far as the application … is necessary in the use as aforesaid of manipulation, remedial exercises, electricity, heat, light, or other approved method.47

Two years later in an amendment to the Cinematograph-Film Censorship Act, the censor was given wider powers to prohibit the display of advertisements for films that contained ‘objectionable’ material. 48 In 1928 efforts were made to enforce a weekly block of time for religious study in state schools and another attempt was made to destabilise the delicate equilibrium that now existed over liquor licensing laws. The era of what the American historian William Leuchtenburg has called ‘political fundamentalism’ was bearing down upon New Zealand; sex, alcohol, disloyalty and greater freedom for women all passed under the scrutiny of legislators. Many were fighting to stave off modern times, growing affluence for some and temptations to many. Similar concerns underlay parliamentary debates on the Chattels Transfer Act 1924 and an amendment to it in 1931. Some MPs felt that credit was too easy to get, and that hire-purchase would open the floodgates to hedonism; the Southland Daily News bemoaned the fact that ‘the unthinking’ members of society were already able to buy goods too easily.49 As the State intervened on behalf of those seen as deserving, there was a corresponding need to regulate the lives of those who were suspected of being improvident. As with the Liberals, state help was for the respectable.

Massey died of cancer on 10 May 1925. Gordon Coates soon succeeded him and was confirmed in office with a substantial victory at the polls on 4 November 1925. Coates was described by one opponent as possessing a ‘radical temperament’.50 He brought to the prime-ministership the same activist inclinations that had been at work in his ministerial portfolios. During the election campaign he promised to introduce what became known as Family Allowances and talked vaguely of a national contributory insurance scheme that sounded not unlike Atkinson’s. The idea was quietly dropped before the 1928 election. However, against the better judgement of some of his colleagues, Coates pushed through the Family Allowances Act during the parliamentary session of 1926. Extolling family values as he went, the Prime Minister established a small, means-tested mothers’ allowance for the third and subsequent children in a family, paid from the Consolidated Fund. Reflecting the same sort of views on social control that had been current at the time of the Old-age Pensions Act in 1898, the benefit excluded mothers of illegitimate children, aliens and Asians.51

Further interventionist measures were taken by Coates’s Government, despite the fact that his caucus was full of people whom John A. Lee colourfully described as ‘elderly men of Victorian sentiment … washed out of their armchairs into the House, where they … busied themselves in trying to turn the clock back’.52 Soon after the House assembled for the 1926 session a Town Planning Bill was introduced, and it became law on 9 September 1926. The need for town planning had been debated since before the war.53 It had been the subject of a special conference in 1919. In the end it was left to Coates’s ministry to legislate. The Act required every local authority with a population of 1000 or more to produce a town plan ‘for … the development of the city or borough … in such a way as will most effectively tend to promote its heathfulness, amenity, convenience, and advancement’. ‘Extra urban’ schemes were also required from rural local authorities. The Act established a Town Planning Director and a Town Planning Board. Initially it was chaired by the Minister of Internal Affairs. Local plans were to be drafted, submitted for public comment then adopted by local authorities before 1 January 1930 – a date that was subsequently stretched until 1932. On 12 March 1927 the Government further promulgated a set of regulations outlining matters to be incorporated in a town plan.54 For the first time, elected local authority members had been given powers to prescribe rules governing private developments in their areas, but the overall parameters were set by central government. A centralising process whereby the Government established its dominance over many aspects of life was gathering pace in the 1920s.

The Motor Omnibus Act 1926 was another piece of legislation increasing the powers of public authorities over private enterprise. For many years it had been permissible for local authorities to establish public transport (usually tramcars) for their citizens. Like railways, their economic viability was now being threatened by motor cars and privately owned bus companies. As with Railways, concern about public investment caused the Government to legislate to protect it. Foreshadowing some features of the Transport Licensing Act 1931, the Motor Omnibus Act divided the country into motor omnibus districts, made local authorities the licensing authorities, and required bus operators to hold a licence to operate. In effect, local authorities could license their own tramcars to the detriment of the private sector. There was a storm of protest from private bus operators, and some sharp criticism of the Government from within its own ranks. Several supporters called the legislation ‘socialist’, somewhat to the dismay of Coates’s ministers.55

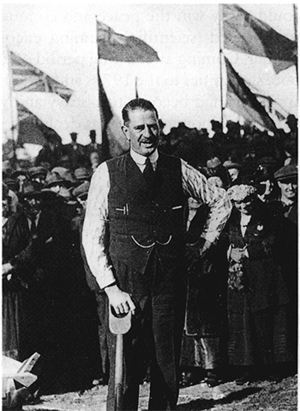

Coates’s campaign leaflet for the Kaipara electorate, 1928.

The rural sector also came in for its share of government activism. The crisis over the London marketing of dairy products in 1926-27 stemmed from over-confidence by the Dairy Board, the leaders of which invoked the full powers of the 1923 marketing legislation to fix butter prices in London and control its marketing. They hoped that British consumers could be forced to pay more for New Zealand butter than current market prices. The debacle has been written about elsewhere. It is a story of bull-headed ignorance by the Board’s chairman, a Hokianga farmer called William Grounds, and lack of decisiveness by the Prime Minister, who dithered long after the perils of what the Board was trying to do became abundantly clear. British consumers boycotted New Zealand butter, which had never commanded more than 25 per cent of the market. Belatedly, at a meeting of the Board on 15 March 1927, the Government forced the Board to back down. Price fixing on the London market ended in a hail of recriminations.56 The incident showed the dangers that could flow from delegating government powers to headstrong producers.

Behind the butter fiasco lay the sorry story of declining prices for New Zealand produce on the London market, largely because of the depressed state of the British economy. Declining commodity prices hurt New Zealand’s farmers, many of whom were finding that their overheads outstripped their income. This was specially true for those who had paid high land prices, and borrowed heavily in the years 1917-21. Ever since the war there had been advocates of cheap credit to farmers. Some wanted a farmers’ state bank – something to which the Secretary to the Treasury, G. F. C. Campbell, was not averse when it was first raised in 1919.57 In 1925 a commission was set up to inquire into the need for financial assistance to farmers. This commission recommended the provision of ‘intermediate rural credits’ in addition to existing long-term advances.58 Coates’s Government accepted the advice. A Rural Advances Act 1926 established a separate branch within the State Advances Office to deal with farmers. In the 1970s this became a separate entity, the Rural Bank. Advances of up to £5,000 in certain circumstances could be made to farmers in need. In the first two years of operation, £2.6 million was authorised.59 In 1927 further legislation was passed. The Rural Intermediate Credit Act provided for assistance to members of co-operative credit associations; further money was lent to farmers through Intermediate Credit Boards. In the first fourteen months of their operation £268,310 was advanced at between 6 per cent and 6.5 per cent. By this time the Government was also paying shipping subsidies (£22,500 pa), subsidies for grading and storing dairy products (£140,000 pa), subsidies to wheat growers (£400,000), and subsidies to Railways for the carriage of lime and fertilisers (£155,000 pa).60

Many years before Pember Reeves had written: ‘In the colonies Governments are, rightly or wrongly, expected to be of use in a public emergency, and under the head of public emergency dull times are included.’61 Coates was proving, yet again, the truth of that comment. As Gary Hawke notes, ‘the close-knit homogeneous [New Zealand] settler community had evolved its own doctrine of what the state apparatus should do’.62 But such subsidies meant that Downie Stewart could not seriously contemplate tax reductions at a time when they might well have helped the ailing economy. A later Minister of Finance faced the same problem at the end of the 1970s.

The United Government tried to cure unemployment by expanding the State’s payroll; postal delivery boys in Wanganui, 1930. ATL F-17061-1/1

During 1927 and 1928 Coates’s Government had difficulty balancing the interests of farmers, manufacturers and workers. It ended up by satisfying no one. Ministers set out to exempt farmers and dairy factories from coverage by the Arbitration Court but staged a partial retreat before an onslaught from workers’ and employers’ representatives. There was tinkering with the tariff in 1927 when the Government sought to reduce duties on some foodstuffs, while providing further protection to industry as well as reducing duties on raw materials. But the changes won little support from sectional forces promoting their own agendas. An Industrial Conference met between March and May 1928 but was unable to arrive at substantial agreement on further tariff reform or changes to the I.C.&A. Act.63 However, assisted immigration which brought into New Zealand more than 11,000 people in 1926 was trimmed back to fewer than 2000 in 1928 and fell further during the depression. The only thing that attracted anything approaching unanimity among the parties was more government expenditure. All parties to the conference supported railway freight concessions, which involved further subsidies.

Presiding over a bearpit of sectional forces, each trying to use the State for its own ends, Coates’s Government achieved little during the 1928 session of Parliament. The Reform Government went down to defeat in the election on 14 November at the hands of a resurgent Liberal Party, now calling itself United. This new party’s origin was largely ideological; its organiser, A. E. Davy, warned in 1927 of the ‘great impetus to the Red Movement’ taking place under Coates’s Government. In March 1928 a gathering of businessmen calling themselves the 1928 Committee identified several areas from which they believed the State should withdraw. They fastened their gaze on state trading organisations such as State Fire and Government Life Insurance, State Coal, the Post Office Savings Bank and the Public Trust Office. Forestry and Railways were both said to have gone beyond ‘legitimate’ (but undefined) boundaries for state activity. However, the anti-state party which businessmen wished to create was snatched from its cradle. The United Party went into the election with the aged Sir Joseph Ward as its leader. A diabetic with a dicky heart and poor eyesight, Ward misread his speech notes at the opening of the campaign in Auckland and promised to borrow £70 million overseas to stimulate New Zealand’s ailing economy. A wave of popular enthusiasm for a further round of state activity engulfed the 1928 Committee and carried Ward into the prime minister’s office, where he led a weak minority ministry dependent on other parties.64 Like Stafford’s Government in 1857, Fox’s in 1869-70 and Grey’s in 1877-79, New Zealanders again thought they saw salvation in borrowed money and state intervention.

Prime Minister Ward, ailing like the economy, on his seventy-fourth birthday, 26 April 1930.

His family and colleagues eased Ward from office in May 1930, a few weeks before his death. He had solved nothing. On 1 October 1929, which had been his last day in Parliament, he promised to banish all unemployment within five weeks. Throughout his career Ward had pushed the State into many areas of the economy. But this was the boldest declaration of government omnipotence to date. A few days after his promise – fortuitously perhaps – Ward was in hospital, fighting for his life. In his absence ministers tried valiantly to put the unemployed to work. While they managed to rustle up 4889 additional relief jobs within government departments, they were overwhelmed by a flood of new applications for work.65

None of Ward’s £70 million was borrowed. Worse, export prices which were New Zealand’s international lifeline were tumbling. Unemployment leapt in an alarming fashion between 1930 and 1933, leading to riots in Dunedin, Auckland and Wellington in the early months of 1932. Decades of heavy borrowing, inflated land prices and a high level of wages by world standards made New Zealand specially vulnerable to the catastrophic worldwide collapse in prices and economic confidence. Ramsay MacDonald, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, labelled it an ‘economic blizzard’.66

Those who remember the crisis of the 1980s may see some parallels in the 1920s: dubious state investments; a mixture of social and business objectives in government ventures that turned them into users of tax revenue rather than contributors to it; a heavy reliance by many on government funding and an over-optimistic confidence that governments could protect New Zealand’s living standards in a volatile world. However, whereas the later crisis called into question the efficacy of government intervention in the economy, the crisis that struck New Zealand in 1929 did nothing to dim public faith in the all-powerful State. Everywhere in the world, the Great Depression ratcheted up the level of government intervention in everyday affairs. Robert Higgs observes that the people who lived through the depression were never the same again: ‘the anxieties and convictions it fostered entered deeply into their attitudes and opinions. The political economy emerged from this wrenching experience altered to its core.’ Higgs notes that in the United States there was a huge increase in the number of believers in the efficacy of state intervention.67 It was certainly the case in New Zealand.

George Forbes has been described by Keith Sinclair as ‘New Zealand’s most improbable Premier’.68 He succeeded Ward on 28 May 1930, heading a minority government. It was supported in the House alternately by the Labour and Reform parties. Neither was keen on the idea of an early election. On 22 September 1931 Forbes persuaded the reluctant Coates to join a coalition ministry and the two together ultimately shared the odium attaching to tough decisions. Re-elected on 2 December 1931, the Forbes-Coates Coalition Government extended its term by one year and ruled until defeated at the polls on 27 November 1935 by the Labour Party.

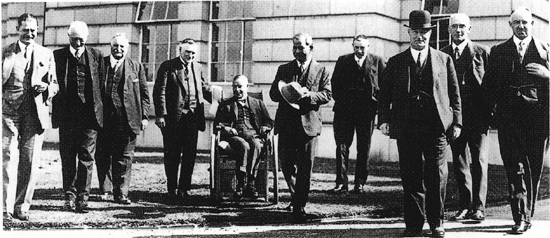

The Coalition Cabinet, 1932: Prime Minister George Forbes in front with bowler hat; Coates, his deputy, far left; and then Minister of Finance, Downie Stewart, in the wheelchair. ATL C-21064

Like the public at large, Forbes and his ministers were alarmed at the escalating disaster. As early as 1922 the Department of Industries and Commerce had been asked to accumulate information from abroad about schemes to reduce unemployment. Officers gathered details about Queensland’s legislation where workers, employees and the State paid equally into an unemployment fund that could be tapped by workers in times of need. As details came to hand they were sent to Reform Party supporters.69 In its dying stages the Coates Government set up a special committee to investigate unemployment under the chairmanship of W. D. Hunt, a Wellington businessman specialising in taxation. The committee’s 22-page report concluded that unemployment resulted from a chronic ‘failure of the consumption of certain goods to keep pace with the production, or the failure of the demand for certain services to equal the supply’.70 It was silent on measures that might be taken to stimulate demand.71

Meantime, economists the world over were arriving at the conclusion that protecting local markets was the best way to encourage consumption, and hence the creation of jobs. Everywhere tariffs were used as barriers against competition from the rest of the world. These policies were gaining academic respectability; John Maynard Keynes argued vociferously for protection throughout 1930-31.72 Reports arriving in New Zealand from the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia all indicated that a wave of economic nationalism was sweeping the world. The New Zealand Parliament established an Unemployment Committee to examine ways of assisting secondary industries to absorb more workers. Manufacturers large and small were happy to cooperate. Most relied on domestic markets and wanted more protection. ‘The safeguarding of our home industries with the adoption of a scientific tariff [is] the only measure by which it will be possible to maintain our people in material comfort and prosperity,’ declared the organiser of the Canterbury Manufacturers’ Association in November 1928. In this context he meant that tariffs should be raised to a level sufficient to make higher cost local goods competitive with imports. Another manufacturer urged that ‘town and country … stand side by side and realise that primary and secondary interests both have their place in the scheme of things, and are complementary – not antagonistic’.73

Smaller manufacturers sought government loans at reduced rates of interest.74 The Christchurch Sun supported a higher tariff so long as it was ‘on a rational, scientific basis’.75 Some farmers, especially tobacco producers, dropped their traditional enthusiasm for free trade as they pushed either for greater protection for their crops, or stepped up their requests for more subsidies. Most farmers, however, wanted to keep and extend their subsidies while denying others a higher tariff.76 The Chambers of Commerce, representing among others the nation’s importers, were not enthusiastic about any tariff increase. Every sector group seemed to feel that salvation lay in accessing government assistance while denying the advantage to others.

During 1929 attention focused more narrowly on New Zealand manufacturing. Relatively few factories employed 100 or more workers in the 1920s, but there had been a mushroom-like growth of smaller establishments, nearly all of them employing ten or fewer workers.77 Few of these had the capacity to expand without substantial assistance. The Manufacturers’ Federation lobbied on behalf of smaller industries in 1929, arguing strenuously for a ‘Development of Industries Board’. Appeals for assistance flooded into the Department of Industries and Commerce. But, as the editor of the Otago Daily Times was to note, industrial growth in New Zealand had been ‘haphazard in the past’, and ‘the encouragement of a lot of small, struggling inefficient industries all clamouring for protection, is not at all what is wanted’.78

Wary of possible retaliation from the United Kingdom if New Zealand pushed its tariffs too high, and sceptical about the capacity of many of New Zealand’s industries to employ many more people, government officials counselled caution.79 A Development of Industries Board was finally set up at the end of 1931 but instead of investigating tariffs, it was to look at a raft of new industries that officials believed might be profitably established, such as the production of pig iron, boosting the iron and steel industry at Onekaka in Golden Bay, the making of Benzol, motor spirit and kerosene cases, the printing in New Zealand of cinematographic films from negatives and an old hardy annual, the flax industry.80 The Board was made up of successful businessmen and officials who shared the views of the new Minister of Industries and Commerce, Robert Masters. Masters wanted to insulate New Zealand’s manufacturing as much as possible. It should use locally produced raw materials wherever possible, or, if this was not possible, only British materials.81

The Board wrestled with the criteria that should determine industrial development, especially new, job-rich industries. From these discussions emerged a new approach to state assistance that seems to have been largely the brainchild of G. W. Clinkard. Born in 1893, Clinkard was a Wellington-trained economist with long experience in Statistics and Industries and Commerce, of which he became Secretary in 1930. He favoured licensing of industries. Once there had been a careful study by officials, ‘something in the nature of exclusive rights to manufacture’ would be granted to a licensed industry – in other words, a state-protected and assisted monopoly would be created. Clinkard amplified his views in a memo to Parliament’s Industries and Commerce Select Committee on 23 November 1932:

It has been represented to the Development of Industries Committee that unless these new industries can have the assurance that no other factory of the same type will commence in the Dominion within a reasonable period of time those interested will not be prepared to invest the necessary funds. To enable this suggestion to be carried out it would be necessary for the Government to prohibit the manufacture of goods in question save under licence to be issued by the Government on such terms and conditions as might be considered appropriate.

Clinkard claimed there were precedents for the granting of monopolies and exclusive rights. Gas and electricity were publicly delivered, while the State itself ran the monopolies of Railways and Post and Telegraph. It also licensed the sale of liquor. Clinkard argued that any granting of ‘exclusive rights’ must always be under ‘proper safeguards’. He listed some tests that should be applied before ‘exclusivity’ was extended to any new industry. The industry must be of national importance; it must be ‘a substantial employer’; it ought to use locally produced raw materials where possible; it should be of ‘economic value’ when compared with overseas supplies; any patents ought to be able to become the ‘exclusive right’ of the New Zealand industry; and the extent to which a large investment was involved should first be the subject of careful bureaucratic study. In Clinkard’s view the State should be able to prescribe a time limit for the commencement of an industry that was granted a licence. Clinkard clearly envisaged that tariff protection would be necessary for an industry that was granted ‘exclusivity’, ‘unless the further step were taken of prohibiting not only competitive local manufacture but competitive importation’. He had every confidence that legislative restrictions and safeguards could curtail any monopolistic tendencies in the interests of the public. The whole submission was posited on the assumption that careful attention to detail by bureaucrats could greatly improve on the market.82

More than half a century on, Clinkard’s ideas seem bizarre. A heavily restricted, state-supported, guaranteed monopoly, enjoying tariff protection, producing what the industry, bureaucrats and ministers thought was in the national interest! Yet, these were the years when many intelligent people were watching the State’s massive involvement in the Soviet Union where the worst effects of the depression had been avoided. The notion that the market was an antiquated instrument which could be ‘scientifically’ manipulated in the public interest also had a growing number of adherents in the West. Franklin Roosevelt was shortly to assume office and the United States Congress would pass a series of acts that greatly enhanced the President’s powers in industry, banking and agriculture. The United States National Recovery Administration soon had power to draw up codes for fair trade and a seal of approval could be given to American industries that were deemed to be cooperating with bureaucrats’ schemes. Clinkard’s views were no more than an antipodean effort to apply a regulatory framework to a vulnerable economy which seemed to have limited industrial potential and no great prospect of developing a full range of competing industries in a small market.

For the moment, however, the Coalition Government was listening more attentively to other advisers who were worried about the dangers of licensing and protecting uneconomic industries. As Coates very rationally stated in 1934: ‘It is … not in general of advantage to this or any other country that an industry should be fostered by tariff protection where direct and indirect cost of that protection is greater than the benefits likely to be derived by the community.’83 Clinkard’s ideas appealed more to the Labour Party. Since the tariff debates of 1927 Labour had unequivocally favoured tariff protection for industries, especially those using locally produced raw materials.84 Labour eventually wove Clinkard’s suggestions into the Industrial Efficiency Act 1936 and the Bureau of Industry that it created. From then on politicians and their advisers, rather than investors alone, would make the key decisions about New Zealand’s industrial structure.

Further adjustments to the tariff occurred during the depression. By now it had become both complex and arbitrary.85 The Ottawa Conference in July and August 1932 obliged participants to review their tariffs and to erect barriers against British products only if protection would give a local industry a reasonable chance of success. If protection was given to a local industry then a British producer must be able to compete on the basis of economical and efficient local production. These were restrictions around which the various dominions’ policy makers manoeuvred gingerly for many years to come. A Tariff Commission was established in New Zealand in May 1933 under the chairmanship of Dr George Craig, Comptroller of Customs. Its report in March 1934 concentrated on the need for a ‘simple’ tariff that would preserve Imperial preference, yet stimulate domestic employment. The report stressed the need to avoid a recurrence of the riots of 1932 that necessitated passage of the Public Safety Conservation Act greatly expanding the emergency powers of central government. Craig noted some of the limitations imposed on policy flexibility by the Ottawa agreements and was most anxious to avoid a situation that could exacerbate domestic tensions.

The Tariff Commission’s report was a cautious document that rode along the high wire at the centre of the debate about industrialisation:

If a considerable proportion of the rising generation of young people in our towns are not absorbed into industrial employment it is difficult to see what economic occupation will be available for the great many of them…. This must not be taken to indicate our approval of the establishment under protective tariff of uneconomic industries.

Yet the Commission was also mindful of manufacturers’ desires for more protection. It fingered one of the century’s key dilemmas when it noted that in certain circumstances a protective tariff ‘may prove less burdensome than a direct dole or allowance, and would certainly be less demoralizing’.86 From this careful balancing exercise emerged a cautious bill that raised some, and lowered other tariffs. The Australians held on to a higher level of tariff protection. The two countries were making their individual judgements about what they could get away with if they wished to secure greater access for their commodities to the British market in the post-Ottawa environment.87

New Zealand’s export prices had meanwhile gone from bad to worse. Between 1929 and 1932 they dropped 45 per cent. A significant increase in the volume of exports only partly cushioned the impact of the price fall.88 Rural incomes in New Zealand contracted sharply and the impact soon spread to towns and cities. Building fell below population needs. Real incomes declined across the board by between 10 per cent and 20 per cent. Government revenue sagged and the trade deficit widened. First Forbes’s Government and then its Coalition successor embarked on drastic economies. Immigration was cut back further in the Immigration Restriction Amendment Act 1931; in 1934 only four assisted migrants came to New Zealand.89

In spite of cautious longer-term efforts to stimulate industries, Forbes’s Government was faced with the immediate problem of ensuring that the unemployed did not starve. In July 1930 an Unemployment Act was passed. It established an Unemployment Board under the chairmanship of the Minister of Labour. Its activities were financed by a tax of 30s per annum on every male over 20. Revenue from the tax was topped up by a government subsidy. Taxes were further raised in 1931, then again in 1932 and 1934, to give the Board sufficient money.90 The Board set up twelve schemes to provide work for the unemployed. 91 In September 1933, when the depression was at its worst, more than 75,000 men were on work schemes, the overwhelming number of them on Scheme 5, which subsidised local authorities to provide jobs, principally on roads, reserves and other public areas. As local authorities found it more difficult to produce work, the Government gradually accepted that there could be subsidised work on private property, so long as those in ordinary employment were not displaced.

At first the Government determined that all applicants for relief from the Unemployment Fund would have to perform some kind of work in return for relief pay. Cabinet resolutely refused to pay a dole. However, it was finally forced to pay a dole in July 1934 because government departments and local authorities had run out of work. By election time in November 1935 more than 25 per cent of all unemployed men were receiving sustenance payments without work. To an extent that was unprecedented in peacetime, the depression involved public authorities, local and central, as well as private companies, in the direction of a sizeable chunk of the nation’s manpower. Few people objected to this expansion of the State’s role.

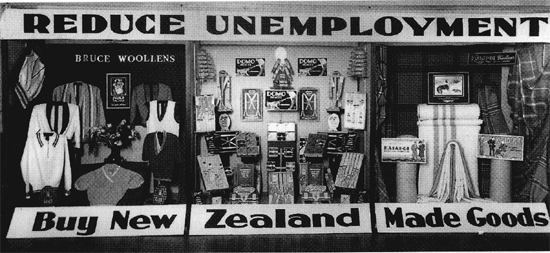

The ‘Buy New Zealand’ campaign, early 1930s. Nelson Provincial Museum

The Unemployment Board kept hoping that the private sector could be stimulated to a higher level of activity. It argued that £10 million worth of goods were imported into the country each year that could be produced domestically.92 Citing advertising schemes being run in Canada and Australia, branches of the Manufacturers’ Federation eagerly took up this war cry. They wanted a subsidised campaign to encourage New Zealanders to ‘Buy New Zealand’. Eventually manufacturers and the Board agreed to share the costs of a newspaper campaign. ‘The Hand that Rocks the Cradle, Controls the Purse – Buy New Zealand’ declared one advertisement in daily papers in September 1930. Another read ‘You Can Help “Square Up” New Zealand by demanding and using the Products of the Dominion’.93

The campaign continued during 1931. Many newspapers picked up the ‘Buy New Zealand’ theme in their editorials. ‘If a locally-made article is purchased, it provides a job for someone to replace it’, the Christchurch Sun told its readers in May 1931. The Dominion even ran articles on its children’s pages exhorting the young to request New Zealand-made goods.94 Goldberg Advertising Agency was paid £1,200, two thirds of it from the Board and one third from manufacturers, for a national campaign. The agency sought and received the support of all party and church leaders for the appeal.95 Follow-up inquiries through district offices of the Department of Industries and Commerce revealed, however, that the campaign had had no perceptible effect on purchasing and was a sorry flop. Meanwhile other nostrums for curing unemployment came in from the public, including the suggestion that leaders should declare New Zealand to be ‘the only real Winter Sanatorium’ to which rich invalids from the Northern Hemisphere should repair, post haste.96

The contraction in government income caused Forbes to establish an Economy Committee of Cabinet under the chairmanship of one of his handful of experienced colleagues, Sir Apirana Ngata.97 The committee met regularly from 6 January 1931 and scrutinised all departmental budgets, looking for ways to reduce expenditure. Interestingly, neither the submissions from the Treasury nor the Public Service Commission raised the fundamental question as to whether departments such as Railways, State Coal-mines, Printing and Stationery, or State and Government Life Insurance should be retained in government ownership.

However, ministers did depoliticise Railways. The Government Railways Board between 1931 and 1936 consisted of ministerial appointees. They were expected to run the services commercially. This inevitably meant an end (temporary as it transpired) to the old practice of running them like an employment agency. By 1934 there were 4500 fewer railway workers than in 1930. Railways accounts soon looked much healthier. The Board was really a forerunner of the corporatisation programme begun by the Fourth Labour Government in 1987. But on this occasion the Railways Board lasted only five years until the First Labour Government in 1936 brought Railways back under ministerial control and returned to the former policy of using it to soak up unemployment. By 1940 there were 25,710 employed by Railways, an increase of 11,000 since 1934.98

Other departments had their budgets pared to the bone during the depression. Departmental giveaways such as annual reports and copies of the Gazette were reduced, as were the railway passes for many categories of public servants, including a very angry Clerk of the Legislative Council. On 14 February 1931 Forbes announced that Arbitration award wages would be cut back and that there would be a 10 per cent reduction in all state salaries. In April 1932 the I.C.&A. Act was amended so as to make arbitration voluntary, rather than compulsory, in the event of an industrial dispute. Award rates fell by an average of 5.5 per cent in the period between March 1932 and June 1934.99 With domestic prices falling, the Government sought to level the remuneration playing field by removing the advantages enjoyed by those whose wages and salaries were still pegged at what now seemed to be high levels; everyone was reduced a notch or two so that no one gained a privileged position from the nation’s misfortunes.

Other measures followed as the Government now tried to raise the entire playing field. Efforts began with farmers whose incomes in many cases had shrivelled to levels not experienced in a generation. In his capacity first as Minister of Public Works and Transport, and then after 28 January 1933 as Minister of Finance, Coates fought at Ottawa for better access to Imperial markets. Then he sought to inflate farmers’ incomes with a 25 per cent devaluation of the New Zealand pound in January 1933, which had the side-effect of making imports more expensive. This byproduct gave an extra boost to New Zealand’s manufacturers. After advice from a group of academics known as his Brains Trust, Coates trimmed farmers’ costs with the establishment of a Mortgage Corporation. He reformed the Dairy Board’s legislation, and in the Agriculture (Emergency Powers) Act 1934 gave power to a newly constituted Dairy Commission to license farmers, supervise dairy factories and determine where dairy products were marketed. Coates gave indebted farmers greater security of tenure of their land with the Mortgagors and Tenants Relief Act of December 1933 and the Rural Mortgagors Final Adjustment Act in April 1935.100 Each measure involved a further extension of the State’s authority. The mortgage legislation gave the State wider powers to scrutinise farmers’ indebtedness and to protect them against lenders than had been enacted during World War I. The new policies undoubtedly protected many farmers faced with foreclosure, although they did little for Coates’s general reputation with the rural sector. He experienced a large swing against him in his electorate of Kaipara, much of it among the very farmers he had helped to save.101

A significant change in the State’s relationship with banking took place in 1934 when the Reserve Bank of New Zealand opened its doors. As Gary Hawke has shown, the idea of a state bank of issue had been around in New Zealand since the beginning of responsible government.102 Whenever interest rates rose and primary producers felt the squeeze, advocates of a state bank emerged, as they had at the end of World War I. During the uncertain 1920s both farmers’ organisations and the Labour Party argued for a central bank with full control of note issue. Sir Otto Niemeyer of the Bank of England recommended setting up a reserve bank in 1931. Downie Stewart, who was Minister of Finance again from September 1931 to January 1933, drew up the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bill; with modifications it was introduced on 19 October 1933 by Coates and passed a few weeks later.103 In Coates’s words the Reserve Bank was designed to:

Assist the trading banks by pooling their reserves, extending them credit in a crisis, relieving them of note-tax, and freeing them of dead gold reserves which earn no profit; it will assist the people by providing a conscious monetary policy in place of the competitive extension of credit which aims at providing dividends for shareholders rather than at promoting the economic welfare of New Zealand; finally, it will make credit easier and cheaper in times of depression, and have a restraining influence to prevent speculation in boom times.104

The bank’s primary duty was to act so that ‘the economic welfare of the Dominion may be promoted and maintained’. This was a significant step in the State’s paternalism towards its citizens, one that the Labour Government built on in years to come.

The Reserve Bank, which was part state-owned, part private, began operations on 1 August 1934 with Leslie Lefeaux, the Assistant Governor of the Bank of England, as its first Governor. In 1936 the Labour Government bought out the private shareholding and the bank came more firmly under ministerial control where it remained until passage of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act on 20 December 1989. That Act defined the bank’s function more precisely, giving it the responsibility for formulating monetary policy that had previously been in political hands and entrusting it with the task of promoting price stability.105

There were many signs of economic recovery by 1935. Export prices for wool and meat were rising and dairy products which had been the last to fall had turned the corner at last. Coates’s trip to London in 1935 to forestall a levy which British ministers threatened to place on all meat imports was successful. Moreover, with their efforts to assist farmers, and the reduction in wage rates in 1931 and 1932 which brought them more into line with lower domestic prices, the Government had succeeded in reducing New Zealand’s cost structure. This gave exporters a more competitive edge in world markets for some years to come.

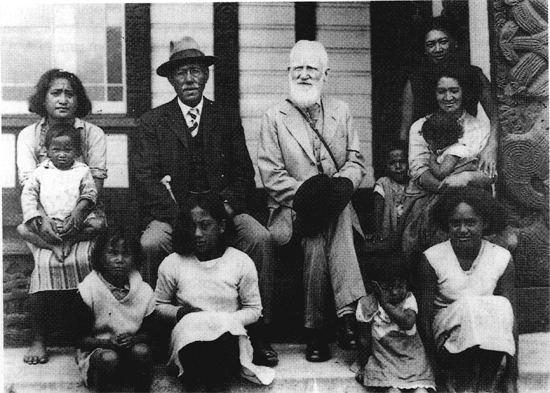

Many conservatives who had been unnerved by Coates’s legislation between 1926 and 1928 reacted with horror at his marketplace interventions. Coates was vilified, particularly by those who lent money and were the victims of arbitrary reductions in the terms of their mortgage contracts. No matter how hard he argued that his reforms were in the wider interests of the country, many refused to listen. One critic accused the Government of practising ‘national State socialism’. George Bernard Shaw’s visit to New Zealand in March 1934 had the unintended effect of adding fuel to the growing right-wing campaign against the Government. From one end of the country to the other, the ‘gangling, opinionated, bumptious’ Fabian socialist praised New Zealand’s active government, calling its reforms, on one occasion, ‘communist’.106 Eventually a third party, the Democrat Party, was set up to fight the election against the Coalition Government, thus assisting its demise.107

George Bernard Shaw meeting with Maori at Ohinemutu, 1934.

Several weeks in the United Kingdom in the middle of 1935 exposed Coates to the new wave of Keynesian thinking that some New Zealanders with an interest in monetary reform had already been talking about.108 In the Finance Act 1935 public service wage cuts were partially restored. Coates was soon talking of resuming borrowing for public works as well. However, it was too late for any stimulation of the economy to affect voters’ perceptions of the Forbes-Coates Government. Conservative opposition to state intervention was simply swept aside by the voters. Public hopes and aspirations now rested with an alternative political force that had woven state intervention into every one of its public pronouncements.