By 10 pm on Wednesday 27 November 1935 it was clear that New Zealanders had elected a new government. Crowds outside newspaper offices in the four main centres enjoyed the fine weather as they watched billboards flashing results. The Labour Party swept to victory, winning 53 seats (soon to be 55) in a House of 80. In front of the Press building in Christchurch a boisterous group watched Coalition candidates topple, chanting as each one lost his seat: ‘Off with his head!’ It might have sounded like the French Revolution to the paper’s editor, who was said to be in tears. Good-humoured Aucklanders greeted each other the next day with ‘Hullo, Comrade’; some wore red.

One of the new MPs, a ‘small, tough, bearded Welshman’ called Morgan Williams, talked of the advent of ‘that Socialist Utopia of which we have all dreamed’. However, after nearly twenty years of struggle to attain office, Labour’s leaders had learned discipline. ‘We have got to have time. We have got to be cautious,’ the new Prime Minister told a Mangere meeting a few weeks later. The London Economist shrewdly observed of the new ministry that ‘the temper of their constituents is too conservative to warrant apprehension’.1 For the most part the Labour Government experimented with planning capitalism rather than building socialism. Nevertheless, Labour wrought huge changes and won the adulation of a wide cross-section of the New Zealand community. The party held tenaciously to office, not surrendering it until 13 December 1949. By then many had come to believe that Labour’s interventionism was one of the fundamentals of the modern state.

While Labour’s seats had grown from eight in 1919 to 24 in 1931, the party’s share of the poll improved only slowly. It moved from 23.5 per cent in 1919 to 27 per cent in 1925 before dropping back to 25.8 per cent in 1928, rising then to nearly 34 per cent in the depression election of 1931. Led by the dour intellectual Harry Holland until he died suddenly in October 1933, Labour sought to entice urban workers with promises of better health, education and housing, while waving land tenure reforms and changes to marketing and credit policies before farmers. For a long time these strategies failed to work; New Zealand’s growing working class, as Miles Fairburn notes, was ‘relatively conservative’.2

During the depression Labour’s leaders devoured books about planning and the public use of credit. For many years now, Peter Fraser and Walter Nash had been attending Workers’ Educational Association summer schools. The books of G. D. H. Cole were much in vogue; they argued the case for a ‘national plan of production’, where ‘the available resources of materials, machinery and man-power are definitely assigned to different branches of production, as they are [in] the Soviet Union’. Labour’s weekly newspaper, the Standard, reviewed Cole’s Simple Case for Socialism, finding it compelling reading.3 Many among a small but growing New Zealand intelligentsia subscribed to Britain’s Left Book Club, initially through the Hamilton bookseller, Blackwood Paul. Tomorrow magazine first appeared in Christchurch in 1934. It has been called ‘the central organ of radical and left wing thought and writing in New Zealand’ in those days. It carried literary work and published articles on a variety of political subjects, many of them critical of the ‘upholders of the present order of society’.

The subtext of most utterances from the left was that state intervention was ‘democratic’ and could not help but benefit the masses. Labour’s new leader, Michael Joseph Savage, declared himself in favour of ‘national planning’. The Standard peppered its pages with talk of ‘plans’, the likely effectiveness of which was never questioned. Occasionally the Standard ran articles about labour experiments in Soviet Russia, such as the Stakhanovite movement, but there was no editorial approval for them, and in November 1936 the executive of the Labour Party rebuffed an application by the Communist Party of New Zealand to affiliate. Yet Ormond Wilson, MP for Rangitikei 1935-38, who had been a student of G. D. H. Cole’s while at Oxford, observed many years later that consciously or unconsciously, Marxist dogma influenced Labour’s policies in the 1930s.4

The unemployed had also spent time reading about political, social and economic problems, as Dr G. H. Scholefield, the Parliamentary Librarian, noted. Evoking memories of the sentimental idealism that underlay the legislation of the Liberals half a century earlier, the Standard serialised Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward during the early months of 1936. Within the public service the culture of interventionism was also gaining adherents; in April 1937 a committee of able young bureaucrats headed by the lawyer F. B. Stephens produced a report for the Minister of Industries and Commerce which acknowledged ‘defects’ within the capitalist system. Noting the worldwide trend towards ‘industrial planning’, the report thought it was ‘a desirable ultimate objective and, indeed, the only logical outcome of present tendencies’. If the Government wished to provide the highest possible standard of living for everyone then ‘they will have to build up a balanced internal economy on as stable a foundation as the structure will allow’. The authors envisaged more central control of the economy than ever before, and clearly relished the challenges this would offer to public servants.5 People in many walks of life now supported state paternalism and were confident about the capacity of a left-wing government to direct it.

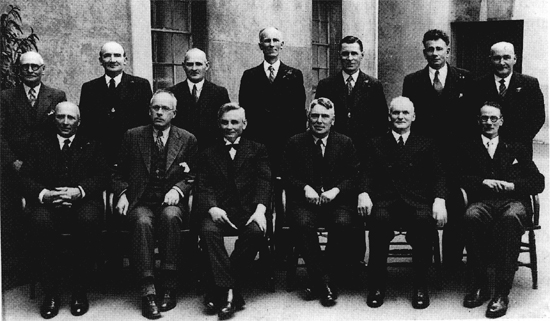

The 1935 Labour Cabinet: front row: W. E. Parry, P. Fraser (Deputy Prime Minister), M. J. Savage (Prime Minister), W. Nash (Minister of Finance), M. Fagan, R. Semple; back row: Lee Martin, P. C. Webb, F. Langstone, H. G. R. Mason, F. Jones, D. G. Sullivan, H. T. Armstrong. National Archives

On the international scene Robert Skidelsky has called the Great Depression a ‘virtual knockout blow’ to economic liberalism.6 In New Zealand the same collapse in incomes that occurred elsewhere, and a precipitous decline in home ownership, gave focus to Labour’s plans. Savage became a vital factor in lifting public confidence. A softer man than Holland, Labour’s new leader has been described as ‘a benign, political uncle, cosy, a good mixer, with a warmly emotional appeal’, who ‘smelt more of the church bazaar and not at all of the barricades’.7 He had a penchant for monetary reform and gave lengthy, often confused speeches punctuated with the exclamation ‘Now then …’. To a Gisborne audience in July 1935 Savage stated boldly that a Labour Government would not borrow abroad for development but instead use ‘the public credit’.

There is plenty of work to be done in this country. Why, New Zealand wants painting from end to end; yet we put painters to work at the end of long-handled shovels. Qualified engineers, bachelors and masters of science, teachers trained at the public expense – all we can find for these people to do is to use the shovel. Under the Labour Party’s policy of using the public credit, there will be no continuance of this system. Every man and woman will be found a place in the economic structure of the Dominion.

Savage was reflecting a climate which now favoured active promotion of employment by the Government and an autarkic approach to the world.8 Savage had a remarkable political gift for personalising his policies, so that people could find in them solutions to their individual problems. After years of relief work and hardship, he became New Zealand’s most loved political leader. His death on 27 March 1940 was followed by an unparalleled outpouring of emotion.

The electoral coalition that brought Labour to power in 1935 was both rural and urban and reflected the depression’s heavy impact on all sections of New Zealand’s population. However, trade unionists dominated the party’s structure. Unionists numbered only 24,000 in 1901, but numbers rose rapidly. According to Erik Olssen, New Zealand was the third most unionised society in the world by 1913, and union influence on the economy grew commensurately. There were 101,000 unionists in 1930 before membership fell away during the depression to 72,000 in 1933.9 Clause 18 of the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Amendment Act 1936 obliged all workers subject to an Arbitration Court award to belong to a union. Membership rocketed to 255,000 in 1939. One old unionist in the Legislative Council warned that this sudden rush of membership was bound to lead to a ‘powerful plutocracy of officialdom that may be tempted to put its own comfort and the emoluments of office before the interests of [union members]’.10 At the time, few were listening.

Many trade unions took advantage of the Political Disabilities Removal Act 1936 and affiliated and paid levies to the Labour Party. The party’s president from 1937 to 1950 was Jim Roberts. He had been an early leader of the Waterside Workers’ Union and played a major role in Labour politics during the depression. Without providing any supporting evidence, Roberts argued that New Zealand’s workers were entitled to a ‘comparatively high standard of living’ because they produced ‘more value per head employed than any other country in the world’.11 Union leaders quickly took advantage of the improving employment situation that developed into ‘over-full employment’ in the 1940s.

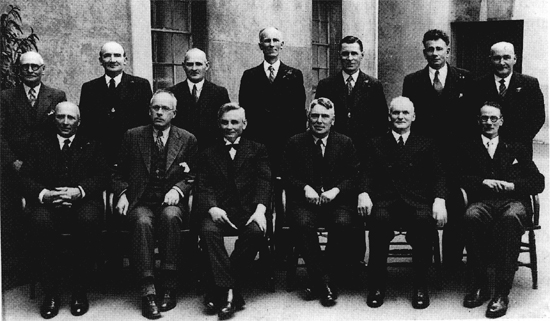

‘Taking up where Seddon left off;’ M. J. Savage alongside a bust of Seddon in Parliament Buildings, 1935. ATL, S. P. Andrew Collection, 18444-1/1

Many union secretaries prospered during Labour’s fourteen years in office. Most worked closely with the governments of Savage (1935-40) and Peter Fraser (1940-49). Fintan Patrick Walsh, who was general secretary of the Seamen’s Union, formed a close relationship with Fraser in his days as Minister of Marine. Walsh passed bits of intelligence to the minister about the activities of some of his MPs.12 The unions usually supported the Cabinet line at annual party conferences, and they dominated party branches in some areas, especially in Wellington. They expected concessions in return for loyalty. ‘Most union members’, writes Olssen, ‘assumed that their … demands were synonymous with the national interest.’13 Walsh lobbied Fraser for legislation that would place workers’ representatives on harbour boards. He also wanted to restrict Railways’ competition with privately owned shipping companies so that the companies could make bigger profits and therefore afford higher wages for seamen.14 Sometimes the Seamen’s Union’s pressure for new manning arrangements for ships cost the Government dearly. Subsidies to the Bluff-Stewart Island ferry escalated rapidly after 1936 and eventually the service proved uneconomic. Shipping to the Chatham Islands suffered the same fate. In retrospect it is clear that many unions secured gains for their members at the expense of the long-term interests of both the public and, ultimately, themselves. Labour MPs found the constant pressure from unionists who seemed to care little about the financial situation increasingly hard to handle.15

‘Big Jim’ Roberts, President of the New Zealand Labour Party 1937–50. ATL C-23146

By the end of World War II trade unions found they had to exert much more pressure if they were to make headway with the Labour Government. Economic stabilisation provided less room for them to achieve sectoral advantage. The Public Service Association under its leader Jack Lewin exercised considerable muscle with some success. A restructured Public Service Commission took office at the end of 1946 with a PSA nominee as one of a troika now running it.16 Trade and public sector unions remained a vitally important component in the advancement of the State’s influence in the economy. Roberts was often derisively referred to by Labour’s political opponents as ‘the uncrowned King of New Zealand’; Walsh, who became president of the Federation of Labour (which was formed in 1937 from an alliance between the old Alliance of Labour and the Trades and Labour Councils’ Federation) in 1953, was nicknamed ‘the Prince’, or ‘Black Prince’, by his detractors. Lewin could be tough as well as rude. After Prime Minister Fraser’s speech to the PSA conference in 1947 Lewin instructed the official party to depart. Many people were beginning to feel that effective power in New Zealand no longer lay with politicians but with trade union leaders. This accounted for much of the hostility to waterside workers when they became involved in a lengthy industrial dispute with the State over wages in 1951.17

Fraser’s confidant, F. P. Walsh (left), discusses transport issues with the Commissioner of Transport, G. L. Laurenson, Secretary of Federated Farmers, A. P. O’Shea and a departmental official. ATL F-34417-1/2

In 1935, however, all this was in the future. There was an air of anticipation as Savage’s Government took office. The New Zealand Herald reported that the public seemed disposed to give the new government a chance to demonstrate its abilities.18 Expectations of heightened state activity were not confined to unionists. Businessmen had been warming to interventionist policies for many years. A leading building contractor, James Fletcher, who already had a string of significant buildings to his credit, told the Auckland Rotary Club in March 1930 that he favoured revitalising industry, using the services of a ‘young, virile, non-political’ Department of Industries and Commerce and a more adventurous banking sector. In Fletcher’s view, professional men and ‘thinkers’ had roles to play as well.

Are they on the running board, or are they behind the wheels of industry with the levers that their professional status and knowledge give to them? I think not. Do they recognise the opportunity in the value of research to assist our car back on to the road, to get its wheels on the metal and clear of the mud and the bog?

Fletcher was calling for a more adventurous State and an active bureaucracy. In the years to come he forged close personal friendships with Savage, Fraser and Labour’s Minister of Finance, Walter Nash.19

By 1934 many businessmen were reading the tea leaves. In November 1934 A. M. Seaman, President of the Associated Chambers of Commerce, expressed the view that there was a ‘tendency towards State control’ and that businessmen ‘should themselves participate in it’. Seaman noted there was ‘more conscious and concerted planning of certain of our national activities’. He thought the trend would continue for some years. He warned his members against being ‘King Canutes’, telling them that it would be wiser to ‘seek to guide the forces that have been loosed, rather than … continuing merely to oppose’. If there was to be paternalistic control then it ‘must be exercised by experienced commercial men’.20 Seaman’s advice was endorsed by the Auckland Star, which noted that the State would inevitably engage in more regulation, and suggested that businessmen should factor this into their plans. The economist J. B. Condliffe, perhaps the best-known of a quartet of Canterbury University College economic thinkers from the 1920s, returned to New Zealand during the 1935 election campaign. He observed that New Zealand’s socialism was divorced from doctrine; it was due instead to what he called ‘colonial opportunism’. He added: ‘Every group has sought to obtain from the State as much as possible.’21 Most sectors of the New Zealand economy were now contributing to what Paul Johnson calls the ‘political framework’ of interventionism that lasted another 40 years.22

Support for state activity from businessmen was tinged with wariness because of Labour’s earlier ‘vestigial Marxism’.23 Labour’s 1918 platform had pledged to extend ‘public ownership of national utilities’ and promised speedy ‘national control of the food supplies of the people’, adding that where there was national ownership of any industry ‘at least half the board of control in each case shall be appointed by the Union or Unions affected’. That platform had also endorsed higher tax on top incomes and lower tax for families.24 Over the years the language became less strident, but Labour’s policy lost none of its paternalism. ‘To build the ideal Social State with the available material is the purpose of the Labour Party,’ declared a policy document issued on 17 April 1933. ‘The purpose of all production, primary and secondary, is to supply the social and economic requirements of the people, and the duty of the State is to organise productive and distribution agencies in order to utilise the natural resources for this purpose.’ The document promised ‘guaranteed prices, organised employment in primary and secondary industries’, and ‘a vigorous public works policy, local and national, at wages and salaries based on national production …’. Secondary industries would be fostered ‘so as to ensure the production of those commodities which can be economically produced in the Dominion, thus providing employment for our own people, with the resultant increase in the internal demand for our primary and secondary products, with less dependency on the fluctuating and glutted overseas markets’.25 Paternalism and protectionism moved hand in hand throughout policy documents.

During the 1935 campaign Savage declared that ‘social justice must be the guiding principle, and economic organisation must adapt itself to social needs’. He talked constantly of ‘intelligent use of the Public Credit’.26 Commentators detected a more doctrinaire approach to the role of government than had come from the leader of any previous government. Professor Horace Belshaw, who had been a member of Coates’s Brains Trust, observed that the new government’s policies rested ‘on the belief that coordinated economic and social planning by the state is necessary for economic and social development’.27

Labour’s bold words, however, were usually matched by an equal dose of caution. Aware of some apprehension in the business and commercial sectors that caused holders of New Zealand securities to sell in the days after the 1935 election, Savage tried to cool things with the statement that it was the new government’s intention simply ‘to begin where Richard John Seddon and his colleagues left off’.28 In the pre-Christmas period the new Prime Minister visited hospitals and orphanages where he distributed presents and told children that he hoped they would see his government as a friend. The Cabinet made several popular gestures including payment of a Christmas bonus to the unemployed and to recipients of charitable aid. Wellington and Otago Training Colleges would reopen, and five-year-olds who had been kept from schools since 1932 as an economy measure were to be readmitted. Relief rates of pay were increased, Maori being paid the same rates as others. There was a general belief in Labour circles that shorter working hours and higher incomes were necessary if a wide cross-section of people were to share in the benefits of improved machinery and technology.29 Early in the New Year the flamboyant Minister of Works, Bob Semple – straying somewhat from Savage’s earlier assurances about the adequacy of local resources – told an audience in Reefton that the Government intended to encourage overseas investment to help with development, and assured investors that they would not be exploited.30 From the very beginning, ministers gave mixed messages.

There were still conservatives in the mid 1930s who opposed state intervention. Some expressed their views forcefully. In 1935 a young Canterbury employer, B. H. Riseley, declared, ‘If we teach the people to rely on the State they will never be able to fend for themselves. Both employers and employees are leaning on the State…. We are teaching our people to rest on the State, and that is wrong.’31 Professional people, especially lawyers and accountants, also tended to keep their distance from the new government. Writing to Coates after the election, an Auckland lawyer said ‘it is surprising how many fellow citizens seem to have discovered that Labour represents just what they have been looking for’. One MP called these people ‘fairweather friends’.32 Yet, with diminishing opposition to state involvement among businessmen and the National Opposition reduced to nineteen seats, there was little option but to engage in constructive dialogue with Savage’s Government.

Labour’s first year in office was its annus mirabilis. Fifty-nine public Acts of Parliament were passed. A further 93 sets of statutory regulations were promulgated, a number that grew to 207 in 1937. The Department of Internal Affairs, which published the Gazette, was obliged to reorganise its printing schedules.33 This new legal framework that emerged set the stage for Labour’s next fourteen years and had a profound influence on the following half century.

Over the New Year 1936 the Government contemplated a radical measure. In order to solve the housing shortage, ministers were contemplating making housing a direct function of central government. They toyed with buying Fletcher Construction so that it could build state houses around the country for rent to low income people. James Fletcher refused to sell his company, but cooperated fully with Under-Secretary John A. Lee, Arthur Tyndall, who became Director of the Housing Construction Division, and the Government Architect while they purchased land and drew up plans for state houses. Within months, Fletchers had won contracts to build houses for the Government in Auckland and Wellington. They averaged 1050 square feet, and 40 per cent of them had three bedrooms. The first was completed in Miramar in March 1937. The Government guaranteed Fletcher Residential Construction Company’s account to an overdraft limit of £200,000 to ensure that there were no construction delays.34 Four hundred units were built in the year ending March 1938. By 1942 the Director of Housing Construction had contracts with 345 builders. A total of 16,522 homes ‘of a modern standard of comfort’ had been completed by then and had been let at a variety of rentals to people in the medium and lower income groups.35 By 1949 one house in every three being built in New Zealand was a state house. The Government had spent £76.2 million in total on rental housing, and more than 6000 workmen were employed by contractors to the Housing Division. Ormond Wilson observed that state housing ‘was … markedly superior to any group housing that had gone before’.36

State houses springing up like mushrooms in Miramar, 1938. ATL F-61277-1/2

State housing was not all plain sailing. Political problems bedevilled the allocation process. Initially there were ballots for the subsidised accommodation, but many who won were clearly less needy than those who missed out. Allocation committees were established in the 1940s. But there was a persistent belief that political influence was necessary to get into a state house. An elaborate points system evolved in the 1970s to determine the priority of cases on the waiting list. Some people found this possible to manipulate, too. Moreover, there was a problem with those tenants whose financial situations, for one reason or another, improved after they got into state houses. Poor people on waiting lists – and there were more than 45,000 unsatisfied applicants in 1950 – resented the growing affluence of some tenants. Short of periodically applying a means test to occupants – which successive governments felt it politically unwise to do – there was no easy way of dislodging undeserving tenants. As Gael Ferguson observes, ‘the Labour Government created a favoured group of tenants who were not always those most in need’.37

Labour’s first piece of legislation was the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Amendment Act which became law on 8 April 1936. It cancelled private shareholding in the Reserve Bank, bringing it firmly under the control of the Minister of Finance. Some Labour politicians held high hopes for the legislation. Clyde Carr, MP for Timaru, saw Keynesian overtones in the measure, claiming it would make money ‘immediately available’ to state departments for restoring depression cuts and lifting salaries, wages and pensions to ‘a decent level’. These moves, he believed, would increase spending power and stimulate demand. Other banks would be obliged to ‘fall into line or get out’. In practice, the relationship between the Government and the bank changed little, as Gary Hawke has shown. The bank – as it had since 1934 – continued to give effect to the cautious monetary policy of the Government. Early in April 1936 Savage gave a public assurance that it was not the Government’s intention ‘to sit down and merely turn the handle of the printing press’.38

Under Walter Nash, Reserve Bank credit helped fund state housing, and assisted with another piece of Labour policy – ‘guaranteed prices’ for dairy farmers.39 The gradual evolution in Labour’s thinking that led to passage of the Primary Products Marketing Act 1936 has been told elsewhere.40 While Labour had promised guaranteed prices to all agricultural exporters, the Bill covered only dairy farmers, since they were deemed to be in the greatest need. Nash had earlier told Parliament that a dairy farmer ‘is entitled to a reasonable payment for the work he does’.41 The Government’s intention was to end the market price fluctuations that made dairy farming such an unpredictable occupation. As in Seddon’s day, the words ‘fair’, ‘just’ and ‘reasonable’ were bandied about. The Primary Products Marketing Bill used the terms ‘usual conditions’, ‘efficient producer’, and ‘sufficient net return’. It spoke of the Government’s intention to ensure farmers an ‘adequate remuneration for the services rendered by them to the community’. Farmers were entitled to a ‘reasonable state of comfort’.42 These were subjective terms capable of many interpretations, but were part of Walter Nash’s flexible concept of social equity. Ministers were setting out on a course of social engineering designed to smooth the hills and hollows of life, lifting some groups and spreading wealth more widely, making use of tax revenue where necessary.43 It became a difficult journey; assistance to one beneficiary often caused envy among others. Under Labour’s paternalistic state the ‘politics of envy’ became a more noticeable feature of political debate. Over time, everyone came to see access to public expenditure as a right; most believed they were not getting as much as someone else.

Intensive negotiations between ministers and the Dairy Board were held during the days before the passage of the Act on 15 May 1936. It was finally agreed that the Government would purchase all dairy farmers’ produce at a set price. The Board would then liaise with the newly created Primary Products Marketing Department to ensure that maximum returns were realised from the on-sale of dairy produce abroad. Money received from sales above the guaranteed price would accumulate in a Dairy Industry Account and be used to subsidise payouts when the overseas market fell. The Government quietened critics of this reduction in the powers of the Dairy Board by ensuring that many Board officials were appointed to the new department. Some Opposition MPs claimed that the Government was ‘confiscating’ farmers’ produce. But this criticism subsided when the guaranteed prices announced for butter (13.5 pence per pound) and cheese (15.1 pence) were higher than could reasonably have been expected from a precise reading of Labour’s election promises.44

In its first year the Dairy Industry Account paid farmers more than was realised from sales abroad. The Marketing Department ran up a debt of £272,000, which was eventually written off by the Government. When overseas prices improved in 1937 and a surplus built up in the account, farmers agitated for a more generous payout. A pattern whereby dairy farmers expected to socialise their losses and capitalise their gains became well entrenched in the years ahead.

The innovations that began in 1936 had some unintended consequences. For a time, the payment on butter fat made the production of liquid milk less attractive for farmers to produce. By 1944 supplies had dropped to the point where domestic town milk supplies were endangered. In the Milk Act 1944 the Government extended a guaranteed price at a sufficiently attractive level to town milk suppliers to divert milk from butter and cheese production for urban supply. However, a combination of guaranteed prices for milk and subsidies that became part of stabilisation during the war kept the price of milk to consumers so low that some farmers worked out that it was cheaper to buy back subsidised milk for stock feed than to use their own produce.45

The Government phased down the central role of the Marketing Department in the post-war years and it was eventually abolished in the early 1950s. Beginning in 1947 its dairying functions were devolved on to the Dairy Products Marketing Commission. In 1952 the National Government won agreement from farmers that the Dairy Industry Account would be self-balancing, thereby ending top-ups from the taxpayer. Price-fixing was transferred to a Dairy Products Prices Authority in 1956, which in 1961 was restructured as the Dairy Production and Marketing Board.46 By this time other forms of assistance to farmers were in place. They covered imported phosphate, subsidies to rabbit boards, funding for herd-testing, payments to the Veterinary Services Council and the hardy annual from the 1920s, the carriage of fertilisers by rail.47 In the meantime, there was no doubt that Nash’s scheme had done much to ensure stability in the traditionally volatile dairy industry. In 1948 an Apple and Pear Marketing Board was created, and in 1953 eggs, citrus fruit and honey, were each put under the producer board system of marketing. In the 1970s kiwifruit joined the other powerful boards, each with a selling monopoly.

At the outbreak of World War II, meat and wool were also brought under the control of the Marketing Department.48 A system of bulk purchasing by the British Government returned; it was similar to that which had operated between 1915 and 1920. Government-to-government negotiations determined prices. A number of advisory organisations were established, including a National Council of Primary Production to advise on all aspects of primary production. In 1946 a Wool Disposal Commission took over the marketing of wool. It was restructured as the Wool Commission in 1952 with the intention of smoothing prices for wool producers. It did so by establishing a ‘floor price’ which saw the Commission topping up farmers’ returns if wool auctions produced prices lower than the ‘floor’. A surplus was expected to build up in the Commission’s accounts in good years. Decisions by the Commission were always made after consultation with ministers.

A Meat Stabilisation Account with a similar purpose was established in 1942. It built up large financial reserves which were used after the war for various forms of assistance to farmers, including research. In 1947 the Meat Board took over most of the Marketing Department’s meat-selling functions. In 1955 the National Government agreed to allow surpluses that had been built up to be used on a price-smoothing regime operated by a Meat Export Prices Committee, which, along with other marketing agencies, was indirectly controlled by the Meat Board. Over the years, governments, no matter which party was in power, played a major part in these developments both with legislation and funding. Since products of animal origin still averaged 65 per cent of the total value of New Zealand’s exports as late as 1979, governments believed they had a vital interest in continuing to negotiate bulk-selling agreements with the British Government. Farmers had learned from experience that governments could be very useful to them.49

After passage of the Primary Products Marketing Act the Labour Government became preoccupied with the concerns of urban workers. Within days of assuming office the Department of Industries and Commerce was requested to report on the likely effects of returning salaries and wages to their 1931 levels. The department generally favoured such a move but pointed out that it would increase the costs of production, and some industries would have difficulty absorbing them. Noting overseas trends, officials told the minister: ‘In order … to secure local industry and to foster industrial development it would appear that equivalent increased tariff or exchange protection, or other control of importations, would be required to offset probable benefits to overseas producers of such [an] increase in New Zealand costs’.50 This protectionist message was taken up by the New Zealand Manufacturers’ Federation, which requested that any wage rise or a reduction in hours worked should coincide with increased tariff protection.

While Labour MPs had given qualified support for raising the tariff in 1934, as ministers they were uneasy, fearing that higher tariffs could collapse the system of primary product quotas so tortuously negotiated at Ottawa. Savage therefore demurred at the manufacturers’ request, but the Government went ahead with the introduction of the 40-hour week. The Prime Minister soon discovered that restoring wage and salary cuts ‘was not as easy as it looks’.51 Those employers who believed they would be unduly affected by the 40-hour week were told to plead hardship to the Arbitration Court in the hope of securing a delay in its application to a particular industry. This proved a vain hope. In June 1938 Judge W. J. Hunter of the Arbitration Court announced that the Court would not be concerned with the ability of an industry to pay increased wages, and that problems with competition from overseas were a matter for the legislature.52

On 8 June 1936 the I.C.&A. Amendment Act became law. It restored compulsory arbitration in labour disputes, authorised the Arbitration Court to incorporate the 40-hour week in awards, and gave the Arbitration Court the power to fix the ‘basic rate of wages’ at a level which in the opinion of the Court would be ‘sufficient to enable a man in receipt thereof to maintain a wife and three children in a fair and reasonable standard of comfort’.53 This ‘family wage’ was a statement of the Government’s social intention which the Court was expected to bear in mind when fixing wages. It bore no relationship to the capacity of an industry to carry any extra costs involved. In the event, the Court’s first effort at establishing a ‘basic wage’ for adult workers announced in November 1936 resulted in a modest increase; the level of £3 16s per week was less than the wage of £4 0s 8d set in 1931 before the cuts. Some Labour supporters were critical of this decision, believing it broke a promise.54 In due course ministers found it necessary to engage in a variety of other measures to ensure that their declarations of social intent could be fulfilled.

In June 1936 the Factories Amendment Act also became law after a slip-up on the parliamentary order paper allowed it to go through earlier than Cabinet intended.55 The Act incorporated the 40-hour week and specified pay rates for overtime. This had major ramifications for employers, and its date of application was delayed until 1 September 1936. Manufacturers’ and farmers’ costs quickly rose. Government departments also experienced higher-than-anticipated wage bills. Rerostering at hospitals opened up job opportunities for nurses, cleaners and kitchen hands. Inflation was already becoming a concern, and the 40-hour week gave it a further nudge, causing problems for the Government’s policy of food price stabilisation. Every government intervention into the marketplace seemed to carry a cost, yet politicians retained a supreme faith that they could regulate or legislate against any unpleasant side-effects of their policies. On 12 August 1936 the Government enacted the Prevention of Profiteering Act in the belief that some prosecutions would deter manufacturers and retailers from making excessive price increases to cover their rising wage bills.56

Dan Sullivan, Minister of Industries and Commerce 1935–47, at the Lipton Tea factory, Wellington. ATL F-70060-1/2

Earlier in the year Labour’s Minister of Industries and Commerce, Dan Sullivan, had gazetted new price levels for flour, wheat and bread under the Board of Trade Act 1919. In his press statement he anticipated that workers’ wages would soon be raised.57 Minimum prices for motor spirits, first set in 1933, were raised in the hope that price cutting could be eliminated. A 3d per gallon gross profit was guaranteed to the retailer so as to ensure ‘a fair return for his labour’. The Standard was enthusiastic about price control: ‘Price-cutters are no good in any business’, it proclaimed. ‘They are responsible for the payment of low wages and the working of long hours.’ Where many saw price-fixing as a device to keep the necessities of life within the reach of the poor, others expected that it would be part of a wider plan that would enable wages and conditions to be set not by the market, but according to some general idea about what was fair and reasonable. Labour’s command economy was moving into top gear.58

Bob Semple (Minister of Works 1935–41, 1942–49), who was responsible for a vast state construction programme. ATL F-115893-1/2

There were problems from the beginning. On 12 August, with new overtime rates and a reduction in working hours only days away, master bakers waited on Sullivan and requested an immediate increase in the price of bread. Five days later Cabinet approved a price rise of a halfpenny per 2 lb standard loaf, taking the price to 5.5 pence, with an extra halfpenny for home delivery. A new set of regulations was telegraphed to all master bakers’ associations. Within weeks there were further complications. Grocers argued that the margin of one penny per loaf for retailing was inadequate, given their requirement to adopt the 40-hour week and the Court’s wage rise. The stark reality was that bakers were not able to control the costs of their materials, and these were rising. It was all reminiscent of problems encountered with price control during the inflationary days of 1918-20. Like his predecessors, Sullivan was finding that price control, no matter how laudable its intention, guaranteed him a hot seat.59

The minister refused grocers’ requests for a price increase, but they then launched a press campaign against the Government. Cabinet held out during 1937. In order to gain better control over prices in this politically sensitive market, a Wheat Committee was set up. Sullivan was its deputy chairman, while wheat growers, millers and bakers were represented on it. All wheat for milling was purchased by the committee and resold to flour millers, who in turn sold their flour, bran and pollard through the committee. By this time flour-mill workers wanted higher wages and disputed that this would inevitably push up the price of bread.60 The reality that labour costs always constituted the bulk of any industry’s costs of production was a puzzle that few union leaders understood.

L. J. Schmitt, a very active Secretary of Industries and Commerce 1935–45, after his retirement. ATL F-88757-1/2

At the beginning of 1938 bakers sent copies of their balance sheets to the Secretary of Industries and Commerce, L. J. Schmitt, with a plea that he intervene with the minister. A deputation waited on Schmitt on 27 January; one baker told him that because of the shorter hours now being worked he was obliged to employ six extra workers; another told the minister that delivery drivers had been paid £3 19s 2d per week at the time of the price increase in August 1936 but had subsequently been awarded £4 7s by the Arbitration Court. Another claimed there had been a drop-off in the rate of work of his delivery staff, while a fourth pointed to a recent increase in the price of motor fuel that his company was having to carry. Collectively they argued for either a reduction in the price of flour or an increase in the price of bread. The Government held out. Some bakers publicly criticised the Government during the 1938 election campaign.61

The Government was in a bind. Many votes could be at risk if there was a bread price rise; on the other hand, holding out against bakers’ demands when their argument was so compelling inevitably led to accusations of unfairness, a concept that so many aspects of government policy claimed to be against. Savage temporised. After Labour’s stunning victory on 15 October 1938 bakers returned to the attack. In a memo to Sullivan on 11 January 1939 Schmitt argued for a bread price rise but floated a new idea with his minister: the Government might care to keep prices stable by paying subsidies on flour. Ministers warmed to the suggestion. Use of government money could get bread price control out of the newspapers. Bureaucrats were soon involved in a major study of bakers’ costs. With the threat of a bakers’ strike before him, Sullivan announced in February 1939 that the Government would ‘grant relief. A subsidy regime that amounted to a cost-plus system was soon in force. It turned bread prices into a matter of regular, behind scenes negotiations between bakers and bureaucrats, with the taxpayer footing the bills.

Standard loaves of bread were kept at a low price compared with other daily necessities until 1977 as part of a growing system of stabilising food prices. In 1942 subsidies were introduced on butter so that its domestic price to consumers could be kept substantially below the export value. Stabilisation as such was defended on the grounds that cheap food helped the poor. When the National Government freed some food items from price control in 1950 it felt obliged to continue subsidising bread and by 1953 the taxpayer was contributing £5 million each year to wheat and flour and an equal amount to butter.62 These costs were now part of an elaborate food and gas subsidy regime that cost the taxpayer £17.5 million that year. The only noticeable alteration to the bread regime was the National Government’s refusal to continue subsidising bread deliveries. This saw the end of home deliveries and of the assortment of bread tins that adorned many verandahs.63

The Government’s food subsidy regime occasionally had unintended effects on the market for other products. With the intention of maximising the production of butter for the British market, the Labour Government retained a restriction on the local availability of fresh cream. Ice cream manufacturers resorted to using subsidised butter in large quantities. When cream became available again in 1950 there was no subsidy to keep its price down, so ice-cream manufacturers continued to use subsidised butter. At the end of 1951 the National Government endeavoured to make them pay the full unsubsidised price for butter; but it soon became clear that pastry cooks and biscuit manufacturers were also availing themselves of cheap butter and any effort to oblige them to pay the full price would be impossible to police. The problem persisted until butter subsidies were abolished in the 1970s.64

Meantime the Labour Government had been seeking to fund employment for those out of work. In the Government Railways Amendment Act 1936 Semple gave the Railways Board of 1931 ‘its running shoes’, bringing operations back into a Railways Department. Once again a general manager was responsible to the Minister. At public works sites wheelbarrows (‘Irishmen’s motorcars’ Semple called them) were abolished in favour of modern machinery.65 The Government authorised new rail and road work, and many airports were soon under construction. State agencies were again expected to fulfil the Government’s employment objectives while delivering their services. The number of Railway employees increased 72 per cent between 1934 and 1940. Not surprisingly, Railways’ net revenue declined sharply until wartime recruitment mopped up many underemployed Railway workers. Public Works employees doubled by the end of 1939; many relief workers who had been on Public Works projects during the depression were transferred to permanent employment and basic rates of pay. The number of Post Office employees also rose by nearly 50 per cent during the same period. While New Zealand’s trading departments were expected to operate as employment agencies they were unable to make business decisions on a strictly commercial basis. However, government policy thinned the ranks of the unemployed, although there were still 8000 receiving the dole in the winter of 1938, with another 30,000 in subsidised work.66

The view reemerged that to work for the Government was a secure form of employment that carried superannuation rights and involved less arduous workloads than the private sector. Not only were agencies such as Railways expected to employ more people than were needed to provide an efficient service but passenger and freight rates were pegged at low levels in the belief that such action would generally assist business and consumers. The concept that there should be an adequate return on capital simply faded away. Dan Sullivan expressed Labour’s view of railways when he said:

The advance of settlement, the opening up of new country and the increase in its productiveness, the provision of employment for large numbers, the cheapening of the means of transport for both goods and passengers, and many other items must all be reckoned as a value obtained for the expenditure in addition to the mere monetary returns earned by the system.

Implementing this philosophy over time became expensive for the taxpayer, especially when Railways needed to invest in new rolling stock. The Government resorted to tougher regulations against competition from road transport in the carriage of bulk goods. But monopoly status did not return Railways to profit, and produced many anomalous situations for those employed in the private transport industry.67

Labour’s activist State found it difficult to engineer job creation in the private sector. Ministers wanted more jobs, especially in manufacturing, which was employing 80,000 workers in 1935. In February 1936 Sullivan outlined his views on secondary industry. His statement envisaged an early version of what came to be known as ‘import substitution’.

I consider that while recognising that for some time to come the welfare and prosperity of New Zealand must be to a large extent dependent upon our export markets, the expansion of secondary industries and the building up of a greater internal industrial system will do much towards the mitigation of the harmful effects of the fluctuations in the prices received overseas for our primary products. It is the earnest aim of the Government to secure the employment in industry of 50,000 odd unemployed workers in this country, and the expansion of our internal industrial system is one of the main methods by which this re-employment can be achieved.68

Implementation was another matter.

Savage told a deputation of manufacturers on 7 May 1936 that he was a ‘visionary’, adding that ‘we must insulate ourselves from abroad’. He believed that it would be possible to achieve this by higher tariffs, by controlling exchange, or by using import licensing. After a great deal of rhetoric, the Prime Minister assured the deputation that the Government ‘realised that as they lifted the standard of life it would require still more protection against the production of lower standard [countries] outside’.69 However, Nash was about to go to London in the hope of negotiating another bilateral trading agreement for New Zealand’s primary produce. He fought strongly against any tariff increases that might anger British exporters, and be seen as contrary to the spirit of the Ottawa agreement. Nash assured the manufacturers that he was prepared to consider other (unspecified) forms of asssistance to industry to enable them to ‘get a decent return on the capital invested and to pay those working in it’.70

In the event, the Government monitored the effects of increased costs on industry, talked of price controls, but tolerated moderate price adjustments, even when these impacted adversely on some companies, especially in the woollen industry. Manufacturers were kept waiting many months before the nature of any further governmental assistance was revealed. Meantime, retail sales increased because of improved spending power. But production costs rose inexorably, and manufacturers were restless at government delays, especially since officials seemed intent on devising more complex forms of regulation for their industries.71

Meantime, Industries and Commerce was developing a system for licensing new as well as existing industries and running an efficiency slide rule over them. Like many ministers, Sullivan had been influenced by Clinkard’s submission to Parliament in 1932, even though he did not like the man. Sullivan appears to have believed that the small New Zealand market meant that in many cases only one producer would be needed to satisfy local demand for a product. However, a bureaucratic eagle eye would be necessary to prevent abuses by any company granted monopoly status. Overseas investors wishing to establish new companies in competition with New Zealand-based enterprises were kept waiting while the Government worked out its policies.72

The Industrial Efficiency Bill, originally known as the ‘Industrial Planning Bill’, was enacted in October 1936. Regarded by officials as one of the most important measures of the year, it gave the Government wide powers to regulate industries. The legislation was described in what was now becoming a ritually paternalistic preamble. It was ‘an Act to promote the economic welfare of New Zealand by providing for the promotion of new industries in the most economic form and by so regulating the general organisation, development and operation of industries that a greater measure of industrial efficiency will be secured’. The Act incorporated a Bureau of Industry which had been functioning since May. This Bureau existed until 1956. It had powers to license industries, to conduct inquiries, and to make recommendations on how best to assist, either by way of subsidies, grants, loans, tariff concessions, preferences, embargoes ‘or otherwise howsoever with a view to the establishment of new industries or the development of existing industries’. The Bureau could prepare plans for any industry and involve itself with the training of skilled people deemed essential to that industry.73 There was no single instrument to assist any particular industry, but rather an array of measures that bureaucrats could recommend to the minister after receiving submissions.

The Bureau of Industry identified many areas where local production could be stimulated to satisfy the local market. Sardine canning, soap, rennet, flax processing, petrol pumps, asbestos cement, tyres and tubes, lacquers, electric ranges, car batteries, radios, linseed oil, woollen goods and wooden boot lasts were all identified as areas for expansion. They were included in a growing number of industries that required a licence. Efforts were made to encourage greater use of coal for electricity generation. In July 1936 consideration was given to boosting imports of completely knocked down (CKD) cars for local assembly – an industry that had begun in a small way in the Hutt Valley as early as 1926. There was much research into the clothing industry which seemed to have the potential for jobs, and interest was soon being shown in the plans of several Australians who were developing a large timber mill at Whakatane and employing 220 people by the beginning of 1938.74

The Bureau’s members consisted of senior public servants. L. J. Schmitt, the new Secretary of Industries and Commerce, chaired the body. An Australian by birth, he had worked as an accountant for Broken Hill Proprietary and had served in the New Zealand Board of Trade’s price control division at the end of World War I before serving as Trade Commissioner in Sydney. The Bureau usually met in the department’s head office in the Government Life Building in Customhouse Quay on Monday afternoons. Initially, members had confidence that tariff protection would afford the necessary level of assistance to developing industries. However, ministers’ unease about a British backlash to higher tariffs led them to explore other forms of assistance, such as subsidies.

In July 1936 Cabinet told the Bureau that it was not government policy ‘to extend financial assistance to any one unit in an industry where that unit was in competition with other units in the same industry’. Ministers and bureaucrats were cautiously feeling their way towards a new relationship between the State and industry. After months of delay in 1937-38 while Nash laboured over trading arrangements with the British, the Bureau decided to recommend several different forms of assistance to new industries depending on what seemed most likely to work. Common to all their recommendations was that there be a series of campaigns to persuade the general public and local authorities to buy locally made products.75

The Bureau set up a specialist committee to handle pharmacy licensing where it was clear that the Government’s intended health plans would involve major public expenditure. In January 1937 the New Zealand Official Drug Tariff and Dispensing Price List was issued. It prescribed limits for quantities of drugs that could be dispensed and stipulated the prices at which they could be sold. Complex negotiations took place between departmental officials and drug companies over what constituted a ‘fair profit’. Eventually a Pharmacy Council emerged from these discussions. It distributed licences to retail chemists according to population needs, and controlled cooperative buying of drugs.76

The Government was no longer acting as umpire between competing business interests; it was becoming a regulating agent, as well as an active defender of those companies deemed likely to provide stability and employment for New Zealanders. The principal agency of State in all this activity was the Department of Industries and Commerce. It serviced producer boards, investigated fruit and vegetable marketing, produced elaborate plans for the tobacco and flax industries, subsidised some industries to keep them competitive, and rationalised and regulated the distribution of a wide range of products. When import licensing was introduced in December 1938 the department became the body that advised the Customs Department on whether to grant a licence and if so, for how much.

A centralised economy on this scale needed expert advice on many matters. In 1937 a Standards Institute was established with Schmitt as its ‘permanent head’. Peopled with representatives of professional bodies such as engineers, architects, chemists and the DSIR, it met from time to time and tendered advice on technical matters. The Institute endeavoured to establish standard specifications for a variety of products such as plumbing and electrical materials, as well as paint that was manufactured in New Zealand.77 The first three years of the Labour Government marked a huge leap in bureaucratic involvement in New Zealand’s economy. The Government Life building became the engine room of the new economy. Ministers and their officials, as Paddy Webb had promised in January 1936, were becoming ‘builders, thinkers, creators, repairers’.78

Registering all existing industries and licensing new ones deemed worthy of government assistance (there were 34 of them by March 1941) was a major bureaucratic undertaking. It involved many application forms and much processing of paper. For a while there was confusion because companies selling motor spirits found they were required to register twice -once under the Explosives and Dangerous Goods Amendment Act 1920 and again under the Industrial Efficiency Act 1936. Meetings of the Bureau often bogged down as bureaucrats struggled over applications for permission to erect or shift pumps at individual service stations. Pharmaceutical licensing was a perpetual nightmare because the Boots Ltd chain was competing very successfully with local pharmacies, which constantly sought protection.79

Licences granted to industries occasionally went to overseas interests. Dunlop, Bristol Myers, Colgate-Palmolive, Philips, HMV, Vesta and Exide Batteries, Beatty Brothers, Electrolux, Felt and Textiles, Slazenger, Phillips and Impey, Reckett and Colman, Bushells, and Korma Mills were just some of the overseas firms that established manufacturing industries in New Zealand under licence.80 However, occasionally the system of licensing produced results which the bureaucrats had not intended. Anticipating that only one licence for a new enterprise would be granted, some entrepreneurs sought and received the licence, then failed to proceed, blocking another who was serious about entering the market. Occasionally bureaucrats got out of their depth. Such was the case with plans to register the Leicester trade.

Leicester goods made from a mixture of wool and silk enjoyed a brief popularity during the 1930s. In September 1936 the Bureau of Industry sought information about the extent to which such goods were being produced in New Zealand. It appeared that some clothing manufacturers made a limited number of items, but bureaucrats formed the impression they could be produced on a much larger scale, with the prospect of many jobs being created. Wearproof Hosiery Ltd of Sydney applied for an exclusive licence and tariff protection and gave a guarantee that they would employ 200 New Zealanders in the production of a range of Leicester socks if they were given a total monopoly of the New Zealand market. Officials, and eventually the Minister of Industries and Commerce, were impressed. Wearproof assured officials that they could retail the Leicester socks at no more than the current landed price of imports. Nash demurred, fearing once more that British manufacturers would deem a ban on sock imports into New Zealand a breach of the Ottawa agreements. Officials at the Bureau of Industry would not take ‘no’ for an answer and continued negotiations with Wearproof into 1939. Elaborate plans were drawn up for the production of up to 300,000 dozen pairs of socks per annum. The surplus would be exported to Australia. However, in the middle of 1939 news that Sullivan intended to license the Leicester trade and provide a monopoly to Wearproof got out. It was immediately clear that during the two years of discussions between Wearproof and officials, existing manufacturers in New Zealand had themselves been responding to fashion demands and were producing a growing array of Leicester goods. Officials backed off. Korma Mills of Australia eventually became involved in sock production in New Zealand, building a large factory in Pah Rd, Auckland. Monopoly status on the scale desired by Wearproof was not granted. Bureaucrats had simply underestimated the capacity of private enterprise to respond to fashion demands.81

The system of industrial licensing intensified the already close relationship between officialdom and businessmen. Each depended on the other; fraternisation grew. As far as the public was concerned, if manufacturers produced goods under licence, then the Government was responsible for the quality of goods. Files of complaints built up; within the garment industry alone they covered everything from the materials used to the accuracy of labelling. In September 1954 Mabel Howard MP, New Zealand’s first woman Cabinet Minister, waved a pair of bloomers in Parliament that she believed were wrongly labelled ‘large’, and complained of lax labelling supervision by the Department of Industries and Commerce!82 By the 1950s there was scarcely any area of industrial production that was not the subject of licensing or bureaucratic scrutiny, much of it ineffectual. Controls and regulations had proliferated like weeds.

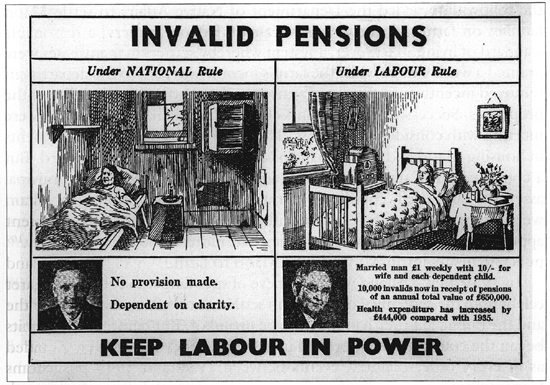

The year 1938 will always be regarded as a landmark in the development of New Zealand’s welfare state. Passage of the Social Security Act in September 1938, a few weeks before Labour’s re-election, marked the high point of public confidence in the all-provident State. In later years Labour politicians viewed it as Labour’s greatest achievement.83 The Act came into force on 1 April 1939. It consisted of a system of state benefits and what politicians intended to be a universal health service. Subsistence payments to the old, the sick, the unemployed and to widows and orphans, most of which had been increased in 1936, were now included in the omnibus legislation. Treasury officials warned against the proposed levels of pensions, arguing that the whole scheme seemed posited on the continuation of ‘a level of comparative prosperity’.84 Health benefits were progressively brought into force over the next few years – mental hospital treatment on 1 April, maternity benefits in May, and free in-patient general hospital treatment in July 1939. Out-patient, pharmaceutical, X-ray and general medical services benefits came in 1941, physiotherapy benefits in 1942, and district nursing (1944), laboratory diagnostic benefits (1946) and dental benefits for children up to the age of sixteen in 1947. Cash benefits were mostly means-tested, but health care was available to all. A special Social Security Fund was established into which was paid a 5 per cent levy on all salaries, wages and other income. There was a registration fee of 5 shillings per annum payable by males aged from sixteen to twenty and all females, and of £1 per annum by all males over twenty. It was envisaged from the beginning that Parliament would have to top up the fund by the amount that these taxes fell short of payouts.85

Various forms of national health insurance had been discussed by politicians and officials for many years. The development of Labour’s ideas from the slogans of 1935 into the comprehensive legislation of 1938 has been discussed elsewhere.86 Many explanations of the need for the Act were given during its germination, none more engaging than the comment of the Prime Minister when dealing with taunts from his political opponents:

I want to know why people should not have decent wages, why they should not have decent pensions in the evening of their days or when they are invalided. What is there more valuable in our Christianity than to be our brother’s keepers in reality? …. I want to see people have security. … I want to see humanity secure against poverty, secure in illness or old age.87

Elsewhere Savage described the Social Security Act as ‘applied Christianity’.

The comprehensive nature of the Social Security Act impressed overseas observers. Writing in 1954, R. Mendelsohn claimed that the all-embracing nature of New Zealand’s legislation influenced Western European policy makers after World War II. The British historian, Asa Briggs, has also noted that New Zealand’s social security legislation ‘deeply influenced … other countries’. By 1940–1 public expenditure on Social Security was more than four times what had been paid out on health and welfare in 1935. By the end of the 1940s New Zealand’s expenditure on Social Security amounted to nearly 10 per cent of GNP. This was proportionately higher than the amount spent at that time in most other developed countries.88

However, when observers spoke of the ‘comprehensive’ nature of New Zealand’s system, they were referring to the fact that the Social Security Act wrapped pensions and health care together in the one piece of legislation. In reality, the health-care component was not comprehensive. It was cobbled together in a series of agreements made between ministers and interest groups over a nine-year period. Each agreement was the best that could be reached at the time. Taken together, there were inconsistencies amongst these benefits from the very beginning. Because of doctor intransigence, the General Medical Services Benefit never covered the full cost of surgery visits. Moreover, there was no mechanism for increasing the benefit so that it would keep pace with inflation. Over time this meant that patients carried a growing portion of the cost of a visit to the doctor. However, pharmaceutical, X-ray and pathological benefits paid total costs but depended on doctor referral. Evidence built up over the years that the very poor were making less use of general practitioners, and it became clear that they were therefore missing out on the other benefits that could be accessed only through a GP. A health-care scheme designed with universality in mind became a boon to the middle and upper income groups who could afford to pay their doctors’ bills and therefore gained access to the other benefits. This was the very antithesis of what Labour politicians originally intended.89

Under the direction of Peter Fraser, Savage’s deputy who took over as Prime Minister on 1 April 1940, there were significant advances in publicly provided education, principally at the secondary and tertiary levels. In 1936 ‘free’ post-primary education was made available to all children until age nineteen. This quickly encouraged all children to seek some secondary education. In 1944 the minimum school leaving age was set at fifteen. When the number of bursaries was substantially increased, numbers attending technical colleges and universities also leaped. The Government was determined to ensure formal education for all who were willing to avail themselves of it. More money for education, as a later Minister of Education, T. H. McCombs acknowledged, was never a problem with the Labour Cabinet.90

While Fraser was largely self-taught, education was his real passion in life. He read widely and developed a talent for tapping the ideas of academically trained minds. Dr C. E. Beeby, who joined the Department of Education in 1938, was a philosopher with research experience at Harvard and a Ph.D from Manchester University. His immediate background was in educational research and he admitted to little administrative experience. One of his first tasks in the department was to write a speech for Fraser. The minister particularly liked several sentences and they have often been quoted:

The Government’s objective, broadly expressed, is that every person, whatever his level of academic ability, whether he be rich or poor, whether he live in town or country, has a right, as a citizen, to a free education of the kind for which he is best fitted and to the fullest extent of his powers. So far is this from being a pious platitude that the full acceptance of the principle will involve the reorientation of the whole education system.

Beeby, who became Director of Education at the beginning of 1940, has spoken of the ‘revivalist’ feeling in educational circles at the time, adding that ‘Fraser spoke what men and women of good will were thinking and groping for’. Fraser’s declaration of intent was never openly challenged in his lifetime.91 Minister, director, educators and most of the wider public accepted ‘equality of opportunity’ and a full and ‘free’ education as laudable goals. Departmental policies were adjusted in the confident belief they could be achieved. Curricula were broadened, class sizes reduced, and libraries improved. Pre-schooling was stimulated. A nutritional supplement for school children was provided in the ‘free milk’ scheme introduced in 1937, at an estimated cost to the taxpayers of £30,000 in its first year. Specialists in speech training were appointed to schools, and there were regular visits by doctors and nurses; they became associated in many children’s minds with a variety of vaccination programmes and the distribution of ‘free apples’, each wrapped carefully in tissue paper. Accrediting of University Entrance was introduced in 1945 and a national School Certificate examination for fifth formers began in 1946. Beeby stressed that it was government policy not to hurt the general interests of a majority of pupils by concentrating on the needs of a few. He added, however, ‘The Department is anxious to maintain high academic standards for the scholarly, but… this end must not be allowed to interfere with the schools’ main function of giving a full and realistic education to fit the bulk of the population, culturally and economically, for the world of today.’ Some critics believed that standards were falling in the quest for equality of opportunity; one newspaper called the new trends in education ‘Beebyism’. In 1978 Beeby conceded that equal opportunity had been much harder to achieve than he thought it would be in the late 1930s.92 Social engineering was moving at a fast pace towards goals that were not always attainable.

An instalment of socialism? School milk after 1937. ATL F-1937-1/4

The huge hike in government expenditure after 1935 – it rose nearly 46 per cent between 1935 and 1939 – when coupled with wage increases, fuelled inflation in the pre-war years. Demand for imports rose steadily and in 1938 there was some capital flight from New Zealand as investors became worried about the magnitude of Labour’s election-year spending. Export prices had already dipped and New Zealand’s overseas capital reserves slid alarmingly. The welfare state’s first election-year foreign exchange crisis – of which there were to be many more – presented Walter Nash with a serious challenge. For months there had been debate among officials about how to respond to shrinking overseas reserves. The conventional response of deflation held no attraction to an expansionary government, while devaluation would have been the reverse of Savage’s earlier promises to return the pound to its pre-1933 value.

Because of fears that higher tariffs would lead to British retribution, the only acceptable option seemed to be some form of direct control on foreign exchange. For many months Customs officials had been gathering material for Nash on protective measures taken in 27 other countries, including Denmark, whose system seemed to appeal to officials.93 On the evening of 6 December 1938 Nash made a major announcement. In order to ensure that New Zealand maintained enough funds to meet its overseas debt commitments, the Government would henceforth license all New Zealand imports and exports; imports would enter the country only under permit. Sterling transfers that drew on New Zealand’s external credit would be restricted by the Reserve Bank.94 In effect the Government now controlled money transfers into and out of New Zealand.

Manufacturers who had been pushing for further tariff protection until the last moment described themselves as being ‘more dazed and bewildered than if a national earthquake had convulsed both islands’.95 They referred to ‘a watertight trade barrier that had been erected around New Zealand’s coasts’ - a comment that echoed the view expressed by a Belgian newspaper a few months earlier when it called New Zealand ‘a sealed compartment, with her frontiers practically closed’.96 Some Labour backbenchers claimed to see import controls as a mechanism that would facilitate construction of a new Jerusalem. W. T. Anderton, MP for Eden and grandfather of the later reforming Minister of Finance, Roger Douglas, told Parliament:

We now exercise control over imports and sterling, and are thus able to prevent a position ever arising again where millions of pounds may fly from our country willy-nilly or at a whim and fancy of individuals who want to spoil the efforts of the Labour Government. Import control has come, and, as a government, we have to see to it that the control is exercised scientifically, and that the things we import balance our exports. We have to see … that the resources we possess within our country are utilized to the maximum for the benefit of this Dominion. There can be nothing wrong with the policy because it involves living within our means and providing a standard of living which, we say, should at all times be maintained…. Within New Zealand we have all the materials and wealth necessary to bring to the people a standard of living far exceeding anything in the world today.97

Savage’s enthusiasm underpinned Anderton’s idealism. At a press conference on 7 December the Prime Minister sang his familiar song about self-sufficiency, telling reporters that ‘scientific selection of imports’ was ‘the practical expression of our insulation plan’. Asked whether luxury imports were likely to be affected, the Prime Minister commented that the luxuries of today were the necessities of tomorrow, and ‘there was nothing too good for the people of New Zealand…. Our job is to provide a foundation for all starting with first things. The best music, the best means of travel, the best education, the best of everything, is good enough for the people of New Zealand….’ Savage concluded with the words: ‘Anyone who attempts to build New Zealand and lift the standard of life without taking a reasonable measure of control of our overseas trade will fall down on the job.’98 To politicians, bureaucrats and social reformers alike, ‘insulation’ seemed to be a vague philosophy of optimism, autarky and nationalism, wrapped in pseudo-scientific clothing.

The ever-practical Nash, however, was more realistic. To him, import controls were essentially a crisis measure to meet the shortage of foreign exchange. He denied that the new controls were socialistic, noting that similar measures had been introduced in many capitalist countries. He promised ‘to provide security and continuity of demand to manufacturers who are entering into the production of commodities at present imported. They will be given a maximum measure of protection so long as they supply commodities at reasonably economic prices’. The minister continued:

The major Government objective is to utilise the resources of the Dominion in maintaining and extending the standard of living of all our people. To do this we must extend production, primary and secondary, within the Dominion to its fullest extent, while at the same time giving maximum trade preference to our best customer, the United Kingdom.99

The Government believed it had found a device that would protect New Zealand industry without pushing up the retail price of British imports, thus jeopardising delicate trade arrangements with London. The quantity of imports would be regulated by ‘scientific’ controls, not the retail price. In the process, ministers and bureaucrats would take unto themselves the task of balancing domestic demand, production and retail prices, adding that to the battery of planning and other functions they already performed. Given the fact that New Zealand was, according to the League of Nations, more dependent on external trade than any other nation on earth, autarky was a policy unlikely to succeed in the long term.100

Importers vehemently opposed import licensing, especially when a continued shortage of overseas funds during 1939 forced the Government to introduce ‘exchange authorities’ which spread the availability of funds over specified periods of time. In May 1939 Gainor Jackson of Devonport, who was a supporter of the National Opposition, succeeded in having the regulations struck down in the Supreme Court. This necessitated validating legislation in the Customs Act Amendment Act of September 1939.101 But, just as most American businessmen adjusted eventually to the New Deal, New Zealand’s manufacturers settled down to tolerate, even enjoy the new regime, although few importers ever reconciled themselves to it. In January 1939 the manufacturers’ journal, the New Zealand National Review, called Nash’s reforms ‘statesmanlike and constructive’. Using language with military images that could have graced a handbook on National Socialism or Stalinism, the Review added a note of warning:

This new progressive and wealth-producing policy will not be implemented and brought to fruition without bitter opposition and ceaseless attempts to sabotage and paralyse it. We are deliberately and determinedly turning aside from the old road of ‘laissez-faire’, ‘rafferty’ rules, and go-as-you-please, and the new one of earning our wealth by the sweat of our brows (instead of borrow-boom-and-burst) is not going to be an easy path to the millennium. Organising our industrial development will demand the best brains and the men most skilled in management and enterprise for the job. They will need cheap capital and credit, willing labour, and fair reward for their work…. Those who direct and control industry must no longer be regarded as predatory capitalists, but as captains of the companies and regiments of industrial production, performing the essential function of establishing the most productive contact between labour and materials.102

Just as ministers believed they were taming capitalism and turning it into something indistinguishable from socialism, so did many in the private sector believe they had ensnared the Government’s apparatus for their own ends.

While there were plenty of conservative critics who protested that the term ‘socialist’ that Labour’s leaders occasionally used was a stage on the road to communism, careful observers were reluctant to dignify Labour’s changes with any philosophical label. Echoing Andre Siegfried’s judgement 40 years earlier, Sam Leathem, an Auckland manufacturer and economist wrote early in 1939: ‘It is probably true that as a people we distrust, even despise theory; we dislike argument on ultimates; we pride ourselves on being practical’.103 In a spirit of paternalism New Zealand’s leaders were feeling their way towards what they hoped would be a fairer society.

Much of the regulatory legislation which passed between 1936 and 1938 was couched in such general terms that it called for judgements from ministers and their officials that many were scarcely competent to make. Moreover, in exercising their judgements they were politicising a great array of decisions hitherto made by private individuals and companies. In so doing, the Labour Government made the business of government infinitely more complex, and helped turn several generations of politicians into ‘Aunt Sallies’ to be blamed for every ill in the land. Yet, Labour’s experimentation had a worthy purpose: the Government intended to see that everyone was adequately housed, fed, clothed and educated. Sixty years later, with the benefit of hindsight, it is a matter of judgement as to whether some of the political decisions, particularly those in the industrial sector, produced more than temporary benefits for lower income people -those closest to Labour’s heart.