In the mid 1960s the Government Statistician, J. V. T. Baker, reviewed the Labour Government’s earlier policy of insulation. He remarked that it ‘required either unlimited overseas funds or irksome internal restraints’.1 New Zealand seldom had enough of the former and within a few years most people believed there were too many of the latter. Moreover, with a high level of government spending on domestic programmes (and Nash spent to the limit each year), more taxes were needed to fund the Government’s growing array of social programmes. However, for several decades after the 1930s the public became accustomed to state experimentation, confident that the politicians – first Labour, then after 1949, National – would eventually find the right mix.

There were occasional threats to Labour’s programme. In 1937-38 the world economy slowed, causing New Zealand’s export prices to slip; many years later, during the First National Government’s term of office, there was a slight recession in 1952-53 as the Korean war drew to a close, causing wool prices to drop. Otherwise, the country’s overseas earnings rose fairly steadily until 1957-58. Only then, with the British already showing considerable interest in a European Common Market, were the first serious questions asked about the sustainability of New Zealand’s insulated, centralised economy. And even then, most people believed that any setbacks would be only temporary.

In 1937 Nash had hoped for a trade agreement with Britain whereby, in return for easy access for British goods to the New Zealand market, Britain would scrap the quantitative restrictions that applied to imports of New Zealand’s primary products after the Ottawa conference. In the event, the British refused to move beyond the Ottawa accords. Nonetheless, prices for New Zealand’s products on the London market did recover in 1939 and bulk purchasing arrangements operated during and after the war, much as they had between 1915 and 1920. New Zealand’s mounting export returns sustained a long period of domestic prosperity which was on a scale unknown since 1895–1920. Governments occasionally required producer boards to retain portions of export income lest its full release added to inflation. While primary producers were seldom content with what they received in the hand and constantly lobbied for full and immediate remuneration, or for government concessions here or subsidies there, the historian can trace a steady upward movement in standards of living, particularly in the rural sector.

Successive governments, however, were constantly confronted with threats to the prosperity they happily laid claim to. As Friedrich Hayek was to note a few years later, societies that were intent on big spending to abolish unemployment found themselves living with the threat of ‘a general and considerable inflation’.2 Inflation became an ever-present danger in New Zealand under the welfare state. Price rises threatened the effectiveness of spending programmes aimed at lower socio-economic groups and put pressure on interest rates; inflation also guaranteed unrest among the unions, especially those that had always been sceptical about the Labour Party or those who believed they could do better by using industrial muscle. Strikes and ‘go-slows’ intensified when inflationary pressures were strongest. Labour’s ministers devoted much energy to price stability. They believed it was essential to their survival in office.

After several years of deflation in the early 1930s, rising prices became noticeable by the middle of 1936. They went up nearly 7 per cent in 1937 following the wage increases of 1936. In all, prices increased 12.5 per cent between the end of 1935 and March 1938. The Department of Industries and Commerce estimated that ‘effective wages’ rose nearly 24 per cent during the same period, which explains Labour’s growing support from the employees and mounting apprehension among employers. By the outbreak of war in September 1939, prices were nearly back to the level of the late 1920s.3

We have already seen how concern about bread prices led the Government into an expensive subsidy programme. Private housing rentals were not handled so easily. On 10 May 1936 Savage announced that the Government would prohibit ‘excessive rents’.4 A Fair Rents Act was passed on 11 June. Like Massey’s legislation that it replaced, it was to exist for one year only but was constantly renewed. It defined a basic rent as that paid on 1 May 1936. In the event that landlords and tenants could not agree on a ‘fair’ rent, then a magistrate would hear the parties and set it. The law prescribed that a fair return on the landlord’s investment was between 4 and 6 per cent of the capital value of the property, plus rates, repairs and depreciation. Some tenants promptly labelled rents set under these criteria as excessive. Landlords’ representatives, on the other hand, argued that more of them would, as they had in earlier years, simply exit the market in search of higher returns. Some did, especially when the provision of state units at subsidised rentals tended to lower private sector rentals. However, the housing shortage in the cities did not go away entirely and demands for ‘key money’ put upwards pressure on rents. A variety of methods was used to get round the regulations. Officials clearly became uneasy about aspects of the Fair Rents Act. Eventually the Government included private rentals in the wartime Economic Stabilisation Emergency Regulations of December 1942. However, throughout the 1940s there were complaints about inequities in the rental market and endless stories of people evading the rules.5

Reflecting the Labour Government’s general suspicion that private entrepreneurs, left to their own devices, would profiteer, the Government retained the Coalition’s controls over phosphate prices, road services fares and freights (1931), petrol (1933), milk (1933) as well as bread and flour regulations dating back to World War I. Savage’s Ministry went further. It imposed controls on butter, cheese, fruit, honey, eggs and onions.6 The deteriorating international scene led ministers and officials to contemplate more controls. In 1937 the Government established an Organisation for National Security (ONS) consisting of top bureaucrats who met within the Prime Minister’s Department under the secretaryship of Lt Colonel W. G. Stephens. Officials prepared sets of controls to be implemented in the event of war breaking out. Most were in draft form by the time of the Munich crisis in September-October 1938. Among them were plans for a price tribunal to administer controls, details of which were approved by Cabinet on 20 September 1938.7 In the meantime, officials used the Board of Trade Act 1919 and its amendment of 1923, plus the Prevention of Profiteering Act 1936, to underpin their surveillance of price movements. On 2 June 1939, by which time inflation was rising in anticipation of war, the Board of Trade (Price Investigation) Regulations were issued. Henceforth prices of goods and services were to be increased only after prior application to a Price Investigation Tribunal. It comprised a Judge of the Arbitration Court and an officer from Industries and Commerce. The tribunal was given the power to fix the prices of goods, including those not previously on the market.

The next price control move was not so carefully planned. When the budget of 1939 increased the sales tax on beer, and brewers were allowed by the new tribunal to pass increased costs straight through to consumers, there was, according to Mr Justice Hunter of the Arbitration Court, ‘hell to pay’.8 On 1 September 1939 the Government rushed through the Price Stabilisation Emergency Regulations. They were gazetted under the Public Safety Conservation Act 1932. These moves took controls a step further. The regulations defined goods and services widely; they declared 1 September to be the ‘fixed day’; and decreed, somewhat cumbrously, that ‘no person who on the fixed day was engaged in [the] business of selling any goods shall sell goods of the same nature and quality in the same quantity and on the same terms of payment, delivery, or otherwise at a price which is higher than the lowest price at which he sold or was willing to sell such goods on the said fixed day’. Similar restrictions applied to services. The Minister of Industries and Commerce was given authority to appoint an investigator with the powers of a judicial inquiry to look into suspected breaches of the regulations.9

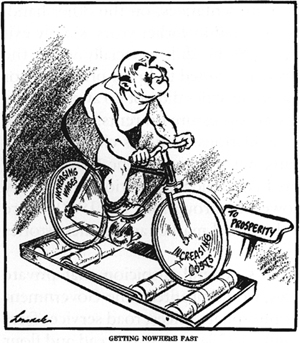

The cartoonist, Lonsdale, looks at the predicament faced by Paddy Webb, Minister of Labour, 1940. NZ Observer

New Zealand declared war just before midnight on 3 September 1939, immediately after Great Britain. For many months Labour ministers had been mulling over their responses in the eventuality of war. For most of them the experience of World War I had been seminal and they were determined to adopt what they called a policy of ‘equal sacrifice’. Both Paddy Webb and Peter Fraser had served time in gaol for opposing the Military Service Act 1916 that introduced conscription. At the time, the Labour Party’s official newspaper, the Maoriland Worker, had fulminated against conscription and Massey’s Government. It accused Massey of ‘fastening the chains of militarism on the young life of the Dominion’ while the Government ‘cringed and grovelled before the profiteer and exploiter’.10 In June 1938 Savage recalled World War I with the comments that ‘while the men were dying, other people were getting rich. That is not going to happen again’.11 Fraser declared in September 1938 that if war broke out ‘all the wealth and all the services would be placed at the disposal of the country’ and that there ‘would be no conscription of human beings without conscription of wealth’.12 A carefully controlled economy was essential to any Labour-run wartime administration.

Many sets of regulations were cleared by Cabinet on 4 September 1939 and promptly gazetted. Factory Emergency Regulations, Electricity Emergency Regulations, Enemy Trading Regulations, Building Emergency Regulations, Wheat and Flour Emergency Regulations, Supply Control Emergency Regulations, Oil Fuel Emergency Regulations, Foodstuffs Emergency Regulations, Medical Supplies Emergency Regulations, Mining Emergency Regulations, Primary Industries Emergency Regulations and Timber Emergency Regulations were promulgated under the Public Safety Conservation Act 1932. Factory, Food, Electricity, Mining and Timber Controllers were appointed, each with wide powers to regulate, control or prohibit activities deemed injurious to the ‘public interest’. More controllers were added as the need arose. Nash made it clear that the war would be financed from a separate War Expenses Account which was to be financed by a combination of borrowing, a national savings scheme and extra charges on stamps, liquor and cigarettes. It was clear from debates in Parliament that there was general agreement that public works spending could be trimmed back for the duration of the war. On 13 September 1939 the Emergency Regulations Bill was given its second reading. Its powers were very wide. Regulations could be issued for many purposes, amongst them ‘the taking of possession or control, on behalf of His Majesty, of any property or undertaking’ or ‘authorising the acquisition, on behalf of His Majesty, of any property’. These moves were justified on the grounds that it was the Government’s ‘duty’ to ‘mobilise the entire resources of our country’.13 They sat neatly with a Government which, in any event, had long decided to command the economy.

The Prime Minister by this time was mortally ill but Savage’s ministers, led by his able deputy, Peter Fraser, were as determined as he had been to guard against wartime speculation and the hoarding of goods. Using their new powers, they hoped to safeguard the economic and social policies that had been put in place over the previous four years. So anxious were ministers about equality of sacrifice that Fraser expressed the opinion at one point that it might prove necessary to put everyone on a soldier’s rate of pay, which at that time was 7s per day. S. G. Holland of the National Party labelled this ‘mischievous humbug and utter rot’; Nash soon conceded that it was scarcely practical.14

Whatever the Government’s intentions – and Sullivan was adamant that ‘fair and reasonable’ prices would be maintained15 - achieving price control in wartime proved extremely difficult. Shipping quickly became chancy, freight costs rose and many raw materials were diverted to war production. Some imported products virtually disappeared. The value of sterling fell on international markets. Moreover, as Schmitt told Sullivan in September 1939, administering the blanket regulations produced ‘some really difficult administrative problems’, not least because there were many commercial people proffering conflicting advice to ministers and officials.16 The Tribunal’s workload increased rapidly and members felt their way forward, seeking the cooperation of manufacturers, grocers and other retailers. Forms setting out the information required by the Tribunal for price rises were soon made available. H. L. Wise, who was Industries and Commerce’s representative on the Tribunal, outlined many of the difficulties in a booklet, War-Time Price Control in New Zealand. In order to smooth the impact of rising prices, the Tribunal began averaging the cost of old and new stock, obliging traders to absorb some of the impact of mounting costs.17

While there was greater restraint of prices in New Zealand than elsewhere in the British Commonwealth,18 it was clear by the end of 1939 that the Tribunal had been unable to enforce complete price stability. On 20 December 1939 Cabinet gave the Tribunal greater powers in the Control of Prices Emergency Regulations. In a controversial move, the Price Tribunal, as it was now called, was allowed to hold judicial inquiries in private or public, as it chose. It could hear witnesses on oath and require the production of all relevant books and documents. These documents were pertinent to the issuing of Price Orders by the Tribunal – of which there were to be more than 500 before hostilities ceased. The documents helped determine whether a uniform price was fixed for a particular locality or for the whole country. So great became the work of the Tribunal that two Associate Members were added in July 1941, one with foodstuffs experience, the other with knowledge of clothing and footwear. Many male and female price inspectors were appointed. By 1942 there had been 430 convictions for breaches of the regulations.19

One particularly difficult application to the Price Tribunal came from Whakatane Paper Mills Ltd. Established with Australian money and the beneficiary of a private act of Parliament in 1936 guaranteeing the company a supply of power,20 the mills began producing cardboard at the end of 1937 and expanded into hardboard. The number of employees reached 220 by the middle of 1938. H. A. Horrocks, the company’s managing director, was a hard businessman, inclined to extravagant public utterances. He constantly sought government assistance, despite earlier assurances to Savage, Sullivan and Nash that the company would be self-sufficient. Like Walmsleys of England and David Henry of New Zealand Forest Products, Horrocks wanted also to expand into the production of pulp and paper but ran up against the State Forest Service’s conviction (supported by the Bureau of Industry) that there should be only one pulp and paper producer, the State. Whakatane Paper Mills Ltd ran up freight bills with Railways and was slow to pay them. Late in 1939 the company applied for permission to raise the price of their products. The Price Tribunal refused the application. Early in the New Year, Horrocks issued dismissal notices to 232 workers, blaming the Price Tribunal and the Government. Horrocks told the press that his directors were ‘not prepared to allow the mill to be run exclusively by bureaucratic control’ and that the Government was attempting to ‘substitute dictation for cooperation’ and that this was ‘strongly resented by Australian interests’.21

Such tactics in a Labour electorate held by the slimmest of margins put the Government under extreme pressure. While for a time ministers seem to have contemplated allowing imports of cheaper board from abroad to compete with Whakatane’s product, they had little political option but to submit to Horrocks. Sullivan agreed to a full, open inquiry into the mill’s accounts before Judge Hunter. On 1 April 1940 a price increase was allowed.22 However, relations between the Government and Horrocks remained bad.

Officials believed that Whakatane Paper Mills was exploiting its monopoly position and in 1941 Cabinet seriously considered taking over the mill and running it for the duration of the war, but delayed a decision, fearing a public reaction. Both Horrocks and David Henry, managing director of another Australian-backed company, New Zealand Forest Products Ltd, kept pestering the Government to allow them to expand into the production of pulp and paper using timber from the State’s forests. In 1941 there were discussions, driven initially by machinery manufacturers, about a state-owned or supported pulp and paper mill. A. R. (Pat) Entrican, Director of State Forests, wanted to ensure that the huge number of exotic trees now ready for milling in the central North Island were processed expeditiously; James Fletcher was more than willing to construct a plant for the purpose. War preoccupations restrained progress but Entrican began gathering information from overseas about what would be required to construct a large, export-oriented pulp and paper mill.23 From this time onwards there were also talks with overseas interests about their possible involvement with a state mill.

What had occurred between the Government and Whakatane Paper Mills was replicated from time to time with other companies. New Zealand Forest Products Ltd was no easier to deal with. In 1943 David Henry attacked the Government over price control and especially over its refusal to grant his company a licence to produce pulp and paper. ‘An industry with immense possibilities is being strangled in a straitjacket of government inertia’, he told his shareholders. This belligerent stance by an organisation with many employees in the marginal Rotorua electorate, which was ‘supported by a well-orchestrated chorus of demands by Forest Products’ shareholders’, eventually won the company a licence to produce pulp and paper. The State Forest Service was granted one at the same time but was in no position yet to take it up.24 What this showed was that large enterprises with many employees strategically located in marginal electorates could bring pressure to bear on any government that was deeply involved in micro-economic management. To counter these pressures, ministers and officials usually resorted either to regulation and/or ownership. This, as will be seen, is what happened with Tasman Pulp and Paper Ltd in the early 1950s. And it became inevitable that the domestic cost structure would rise when either monopoly status or political lobbying, or a combination of both, enabled well-placed manufacturers to bullock their way past normal licensing procedures.

The Labour Government found it difficult keeping abreast of the myriad of regulations, controllers, tribunals and inspectors that they established during the war. Departments were spread over a wide area of central Wellington by 1940. As Savage’s health declined, and he spent more and more time either in hospital or at his home at 66 Harbourview Road, Peter Fraser took effective control. He insisted that all departments keep his office informed of developments. Under Fraser’s command the Prime Minister’s staff expanded rapidly. Fraser came to rely on a group of senior officials, including Joe Heenan, Under-Secretary of Internal Affairs, Bernard Ashwin, Secretary to the Treasury, and Carl Berendsen, Foss Shanahan and Alister McIntosh from the Prime Minister’s Department.25 By December 1940 regulations, some of them drafted by the Law Drafting Office, others by the Crown Law Office and several from departments on their own initiative, were flowing so fast that Ashwin complained to Nash, who requested that henceforth all regulations be prepared in the one office.26 For a time central control was re-established, but in June 1942 Heenan, whose department was responsible for publishing the Gazette, insisted that the Law Drafting Office should now draft all regulations and then submit them to ministers through the Prime Minister’s Department.27 In the superheated wartime atmosphere structures could change daily and the records provide frequent examples of overlapping jurisdictions and administrative snafus.

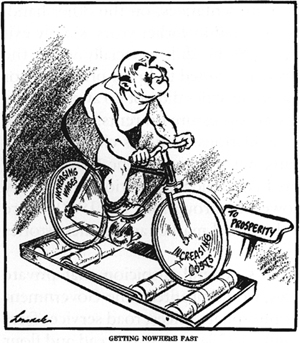

James Fletcher, Commissioner of Defence Construction, 1943. ATL F-606-1/4

Fraser himself worked extremely long hours and his routine was chaotic. Surviving on a diet of tea, toast and cream cakes, which he would devour at any time of the day or night, he kept his key officials around him until the small hours of the morning, sometimes insisting that they accompany him home for further discussions. They in turn, with the exception of Berendsen, who loathed him, developed huge respect for the Prime Minister’s intellectual abilities and were constantly worried about his, and his wife’s, health (she died early in 1945). While Fraser could be petty and sometimes wasted time arguing over trivia, his determination to win through never faltered. In the eyes of his supporters, who included most of the civil servants with whom he dealt, his was one of the most powerful intellects to which they were exposed. Quoting poetry one minute, then revealing an almost photographic memory the next about some small detail buried in a submission to him, the former watersider’s views of the role of the State ruled unchallenged for the duration of the war.28

The Government’s anti-inflation policy came under serious challenge in 1940. The Department of Industries and Commerce acknowledged in its report for the year ended 31 March 1940 that effective wages had fallen nearly 4 per cent.29 Trade unions lodged claims for substantial wage rises and tried to get confidential information from the Price Tribunal to assist a series of cases before the Arbitration Court.30 Deputations of workers and employers plagued ministers with bits of special pleading. In May 1940 the Court was authorised to issue blanket general wage orders applying to all workers under its jurisdiction. The first General Wage Order (5 per cent) was issued in August 1940.

Further steps had to be taken. Fraser convened a conference at Parliament on 4 September 1940. It represented most productive sectors of the economy and considered what was now referred to as the policy of ‘stabilisation’. Besides Fraser, there were three other ministers present: Nash, Sullivan, and Lee Martin, the Minister of Agriculture. The Prime Minister told the sector representatives that the war was obliging the Government to engage in ‘planning on a large scale’ and that this required cooperation from all sectors ‘in a big and generous way’. He wanted those present to assist with policies that would enable the war to be handled ‘in the most fair and equitable manner’. After surveying the economy, delegates were invited to consider ‘the possibility of stabilising costs and prices and wages and to discuss expanding production so that the strain of war expenditure may be successfully borne and the standard of living maintained as far as possible’.31

When Fraser finished, Nash delivered a homily about the need for the current generation to carry the cost of the war rather than loading it on to posterity. Just as he had indicated a few weeks earlier in his budget, he proposed to use taxation and as little borrowing or Reserve Bank credit as possible, so as to keep the lid on inflation. But further price controls would be necessary. After much posturing, during which farmers and mine-owners criticised the lack of ‘high pressure’ work by employees and unionists responded in kind, the conference settled down to consider a list of options and alternatives. The stamp of officialdom and the wily interventions of Fraser’s trusted lieutenant, F. P. Walsh, can be seen in the list of recommendations drawn up by a committee of the conference. The committee met various sector controllers. Members grilled Wise of the Price Tribunal, then listened at length to L. J. Schmitt of Industries and Commerce. He surveyed his department’s activities since 1936, praised the lift which import licensing had given to many industries and painted a picture of his department as the nerve centre of the economy. Schmitt’s enthusiasm for the certainties which planning guaranteed to manufacturers would not have been out of place in a Soviet five-year planning exercise.32 The result was that committee members eventually recommended equal sacrifices, the maintenance of relative living standards and the stabilisation of wages and essential food, rents, clothing, fuel and light. State subsidies, they said, should be resorted to only when they ‘cannot be avoided and then only under stringent control’. Finally, the committee supported a national savings scheme and endorsed family allowances, especially for those with large families.33

However, the Government did not take all the advice immediately, persisting instead with existing policies. Wages were kept under tight control; the Court was restrained from awarding increases at intervals of less than six months. Sales taxes doubled, customs taxes rose, a new scale of death and gift duties was introduced and income and company taxes increased. The top tax rate payable on earned incomes above £3,700 rose to 77.5 per cent.34 A list of 38 commodities on which prices were ‘stabilised’ was put into operation on 1 September 1941.

However, prices continued to rise. Labour Party activists became restless. The language of sacrifice was not enough. Fraser, Nash and Sullivan were peppered with letters of concern from union secretaries. The Wellington Labour Representation Committee told Sullivan in April 1942 that it was firmly of the opinion that the Price Tribunal was proving unable to ‘prevent exploitation’.35 A further 5 per cent wage increase was paid from 7 April 1942 but it was restricted to males earning less than £5 per week and women earning less than £2 10s per week. Price Control officials were now encouraged to tour the country, explaining their methods of operation to interest groups, especially workers.36 The Government was finding it extremely difficult to fight a war, especially one that was at its most desperate stage, while maintaining its social policies at the same time.

By the end of 1942 Fraser had no option but to go further again. For some months now the Economic Stabilisation Committee had been arguing for more controls.37 On 15 December the Prime Minister announced what he called a ‘Charter of Economic Security’. The Government intended to stabilise the prices of 110 items and individual rates of pay, incomes, and rents. Farm products, many of them already stabilised, were not to increase in price and any returns from exports above that price were to be paid into ‘pool accounts’. Land prices were soon controlled and transfers made subject to approval of a Land Sales Court. The Prime Minister conceded that ministers had been aware for some months that existing controls were no longer adequate and that they were worried at the growing evidence of black marketing. In a lengthy statement of the Government’s philosophy, Fraser added:

Seven years ago the Government… pledged itself to the ideal of social security, to the ideal of a society in which the fear of poverty should be banished from every home. That ideal is well on the way to being realised…. Now social security implies something much more than a system of money benefits for people who have suffered unemployment or some economic misfortune. It implies an order of society in which every citizen – wage earner, trader, professional man, or pensioner – is safeguarded against economic fluctuations. It is my plain duty to say that social security in this wider sense of the term is in danger. … It is in danger because the impact of war has let loose forces which, if they are not firmly checked, will throw our economic system into disorder.38

To underline the importance which the Government attached to stabilisation, the burly Bernard Ashwin, Secretary to the Treasury, was appointed Director of Stabilisation. He headed a six-man commission made up of politicians and sector representatives which lasted, albeit with changing personnel, until 1950. They included F. P. Walsh, who was soon occupying an office in Treasury House in Stout Street. The group of people with effective control over the wartime economy had narrowed even further.

An understanding was reached with Walsh that there would be no more wage rises for the duration of the war unless the Wartime Price Index showed that prices had increased by more than 5 per cent.39 To keep the lid on prices, the Government had no option but to resort to more subsidisation of essential commodities. Treasury tried, not always successfully, to maintain a clear distinction between inherited pre-war subsidies and those which could be charged to the War Expenses Account. Costing £500,000 in 1938-39, the amount paid out in subsidies rose to a net £6.6 million in 1945-46, with meat, sugar, tea, clothing and coal all having been added to the pre-war list. By this time subsidies were the equivalent of 2.5 per cent of national income. In the words of J. V. T. Baker, they were now ‘a significant component of the New Zealand pattern of financial transactions’.40 And even with subsidies, as Ashwin pointed out later, prices at times ‘did come close to the agreed 5 per cent… mark and it was necessary for the Government Statistician to do some juggling’. On one occasion higher onion prices threatened to tip the index over the 5 per cent threshold. Ashwin recalled later: ‘I told [the Government Statistician] the country’s economy was not going to be upset by the price of onions and so we withdrew the item [from the list] and got below the 5 per cent mark again. The country was saved!’41 Later in the decade, however, onion prices were subsidised for a time when officials no longer felt so free to tamper with the index.

The advent of stabilisation in December 1942 marked the beginning of a process linking wage increases to movements in the price index rather than to productivity growth. Although the Wartime Price Index was removed in June 1945, indexation of wages continued to be seen as a key element in stabilising New Zealand’s economy. Primary producers’ pool accounts became an equally vital component of stabilisation. By regulation they retained a percentage of the generous returns which agricultural products were receiving from the British. Between 1942 and 1946 more than £23 million was retained in farmers’ stabilisation accounts and by 1951 this had stretched to £116 million. Had the money been paid straight across to farmers as it had been in similar circumstances in 1914-19, it would greatly have fuelled inflation. One economist expressed the opinion to the author that the pool accounts were possibly the most important measure in holding wartime inflation.42

Stabilisation rested on several foundations. First was the relatively conservative fiscal policy followed by Nash during the war years. He budgeted for surpluses and this restrained inflation. Secondly, there was a public acceptance that the relative economic standing of various classes at the end of 1942 would be frozen for the rest of the war. There was certainly very little room for changing relativities, although there were several amendments to the Economic Stabilisation Regulations after 1942, to enable some levelling-up of wages for poorly paid workers, who would be unfairly treated were they to be frozen at their December 1942 levels. In 1945 the Arbitration Court began the practice of standard wage pronouncements. Under these, further small alterations to relativities were incorporated into across-the-board wage increases. Overall, however, the system was fairly rigid. Gary Hawke shrewdly observes: ‘The whole structure depended on the willingness of groups within the community to subordinate their interests to the perceived need for resources to be mobilised towards the war.’43 Once the war was over, the willingness to accept a freeze on relativities slowly evaporated. As some appeared to do better than others, the politics of envy became more ingrained in everyday life. What has often been referred to as the New Zealand ‘tall poppy syndrome’, whereby those with apparent advantages are chopped down by the envious, received a significant boost in the aftermath of war.

While the macro decisions worked well overall, micro efforts were not always successful. One example relates to efforts in 1942 to control clothing prices, which seemed to rise inexorably. The Standards Institute’s staff was boosted and it was set to work on cost-saving devices. Reviving something that had been contemplated by Massey’s Board of Trade in 1919, Sullivan persuaded Cabinet on 23 October 1942 to direct the Factory Controller to enforce Standards Institute specifications for the production of ‘austerity clothing’. Officials were convinced that private enterprise could be directed to get more finished products from the scarce cloth they were using. They spent many hours calculating the annual clothing needs of the population. After discussion with interested parties, the Shirts and Pyjamas Manufacture Control Notice was issued on 29 October under the Factory Emergency Regulations 1939. It provided that no owner or occupier of a factory within the meaning of the 1939 regulations ‘could manufacture any men’s, youths’ or boys’ shirts or pyjamas in contravention of the provisions of the said specifications’. Other rules governed the making of men’s trousers, while there were also specifications for women’s and girls’ clothing and knitwear. The production of plus fours and similar trousers was prohibited; limits were placed on the number of pockets in trousers; and the width of the legs was to be standardised. Hem lengths for dresses were prescribed by regulation, as well as the number of buttons. The regulations stipulated limits on the number of pleats in men’s and boys’ trousers; they specified the size of ‘turnups’, and even attempted to do away with buttons on boys’ knickers and on short trousers! The Standards Institute also turned its attention to the size and quality of hankerchiefs and a control notice was issued later dealing with men’s and women’s outer clothing. Clothing inspectors began calling on factories to ensure that the regulations were complied with.44

There were problems from the start. At the point where the regulations came into force many manufacturers had forward orders for goods that were outside the specifications. The Bespoke Master Tailors Association complained that it had not been represented on the Standards Institute’s committee. Kirkcaldie and Stains were told to write to the Factory Controller explaining why they were not complying with the regulations. Some tailors simply refused to fall into line. They were buoyed by the clear signs of public resistance to ‘austerity clothing’. Lists of pending prosecutions built up. Worst of all, the intended savings did not eventuate. The notion, so fervently believed by bureaucrats, that private manufacturers were wasteful turned out to be an illusion. The Government pressed on for a time, issuing new regulations covering men’s work clothing. However, by October 1944 the Factory Controller’s enthusiasm for the experiment was clearly waning. 45

Walter Nash and Peter Fraser meet over a cup of tea in Washington DC, 1944.

The work of the various wartime control agencies is worthy of brief mention, if only to show the extent to which wartime anxieties bred authoritarianism. The ONS had set up a National Supply Committee. Sullivan became Minister of Supply and Munitions when a War Cabinet consisting of Fraser, Nash, Frederick Jones (Minister of Defence) and two Opposition members, J. G. Coates and Adam Hamilton, was sworn into office on 16 July 1940. A Supply Council under Sullivan’s chairmanship with Ashwin as his deputy, met regularly. In 1942 representatives of the Joint Purchasing Board of the American Forces in New Zealand also attended meetings. By now there were thirteen controllers, all with wide powers. At the end of 1942 they were placed under the direction of a triumvirate consisting of G. H. Jackson, who was Director of Production, F. R. Picot, who was Commissioner of Supply, and L. J. Schmitt, who was Wheat and Flour Controller. Schmitt was also responsible for flax production, tobacco supplies, the Bureau of Industry and the Price Tribunal.46 The Ministry of Supply with a staff that grew to 550 introduced motor fuel rationing in the early days of the war; it lasted until 1 June 1950. Sugar, tea and clothing rationing followed in 1942 and in 1943 butter was also rationed. Ration books were issued and individuals were restricted to 8 oz of butter per week in order to release more for the armed forces and the British. Meat was rationed between March 1944 and September 1948. Some other items such as cheese and eggs remained in short supply. Most rationed items were price-controlled and subsidised. Rationing and subsidisation were seen as ways of ensuring shortages did not drive up prices and that everyone therefore had equal access to a limited supply of goods. However, as J. V. T. Baker points out, shortages, rationing and price control led to black marketing. Several retailers were jailed for illegally selling motor spirits in 1942; but the sale of farm produce was harder to control and by the middle of the year it was common knowledge that there was a large illegal market for eggs in both Auckland and Wellington.47

On 14 January 1942 regulations were issued giving the National Service Department powers to direct men and women to fill gaps left in ‘essential industries’, many of which were struggling to find enough workers to satisfy orders. It was soon clear that officials had underestimated the number of industries wishing to be categorised as ‘essential’. A second list had to be issued on 10 February 1942. During the first six months of 1942, 5000 ‘direction orders’ were issued; these rose to 15,000 during the second half of the year. Before the war finished 176,000 orders had been issued.48

From September 1939 the Building Controller was given wide powers. He could set rules for the granting of building permits by local authorities. In 1941, to ensure adequate materials for defence construction, he banned the large-scale use of reinforcing steel and corrugated iron in any private construction work. Many private house designs were changed to take account of the shortage of roofing and other materials. 49 On 11 March 1942 James Fletcher was appointed Commissioner of Defence Construction and given the widest powers. ‘For the purpose of exercising his functions’, said his terms of appointment, ‘the Commissioner may give such directions as he thinks fit to any officer of the Public Service in relation to the exercise of any powers possessed by them, whether under any Act or regulations or otherwise, including any powers that may be delegated to them by any Minister or other authority.’ The fact that Fletcher drew no government salary and held his position because of his close contacts with ministers, with whom he was on a first-name basis, greatly increased his mana. His methods were unorthodox but the respect in which he was held enabled him to operate effectively between 1942 and 1945.50

The dynamic Fletcher was not the only person given wide powers by Cabinet minute. Ashwin was appointed Deputy Chairman of the Supply Council in the same manner and had no statutory authority for the exercise of his powers. His job was to ensure there was enough military equipment for the country’s needs. Ashwin coordinated, directed, coerced, cajoled and improvised for several years, using commonsense and the high degree of natural authority that he possessed. At one point, on his own admission, he summarily shifted ammunition production from Mt Eden to the Waikato to ensure greater security of production.51 Arbitrary rule was not uncommon during the darkest days of the war.

Meantime, in Customhouse Quay the Department of Industries and Commerce and its associated agencies were toiling away on their manufacturing policies. By the end of the war 6300 manufacturing units in 36 branches of business had been registered with the Bureau of Industry. They were employing 122,500 workers, 41 per cent more than were in factory production in 1935. Engineering had been the biggest single area of expansion, although footwear, clothing and the woollen industry all saw their employees increase by more than 50 per cent over the decade.52 Whether the growth stemmed from bureaucratic intervention or was the product of the highly protected environment in which manufacturers now operated, or whether their wartime contracts were of critical importance, or some mixture of all these, will always be debated. Certainly much industrial activity during the war was the result of contracts secured through the Supply Council to provide for New Zealand’s armed forces, the American forces in the South Pacific and the Eastern Group Supply Council. Airline lubricators, boots, chronometers, overcoats, ladders, nails, waterbottles and radio equipment were exported to assist in the wider war effort. Many new small industries using a variety of improvised methods sprang up in 1940–42 to service wartime needs. Metal buttons, typewriter ribbons, inks and stains for footwear, potato-sorting machines, enamel stewpans and casseroles, gas-producing machines for automobiles, can-sealing compounds, plywoods, egg-grading machines and wooden handles were also produced. Several things were manufactured in New Zealand during the war that were never produced again.53 After an initial burst of licensing new industries in the late 1930s and producing plans for some of them, the Bureau of Industry settled on between 32 and 36 licensed industries for the duration of the war. The Bureau simply lacked the personnel to engage in the full-scale planning necessary to license any more.

Industries securing wartime contracts from the Government almost always found them lucrative. Urgency meant that competitive contracting was replaced with ‘cost-plus’ contract work, much of it allocated on terms that proved expensive to the Government. Sometimes resources were wasted. Contractors were paid for proven expenditure with an additional percentage to cover overheads and profit. Some contractors managed to wring an extra percentage from the Government, exploiting ‘to the full’ their strategic positions, according to the Audit Office. Specially generous contracts applied to private construction of buildings, ship construction and repair work, and for the manufacture of munitions. Normal marketplace risks were replaced by an unprecedented degree of comfort and security for many manufacturers.54 F. J. Pohlen, who was accountant at the Ministry of Supply and Munitions, told a meeting of manufacturers in 1944 that a ‘cost-plus contract’ paying a return of 6 per cent on the capital employed in the production of munitions after payment of the standard income tax ‘must be regarded as almost a gilt-edged investment. There is little risk of loss under the contract and it gives a better return than, say, a Liberty Bond or an investment in the Victory War Loan.’55 Even the Excess Profits Tax after 1940 failed to dent many contractors’ enthusiasm for ‘cost-plus’. Like many before and since, they liked the predictability of doing business with the State.

General Freyberg with Prime Minister Fraser in Italy, 1944; winning the war and getting alongside the soldiers was part of Labour’s political strategy.

The case of J. Watties Canneries exemplifies one wartime relationship that developed between a well-placed company and the Government.56 In December 1941 Treasury guaranteed the company’s overdraft to a limit of £8,000 to enable it to install new can-making machinery deemed essential to provision the troops. In March 1943, on the recommendation of the Food and Rationing Controller, the company secured a government building loan of £8,500 at 5.26 per cent to enable it to erect a building and expand into dehydrating vegetables and fruit for the American and New Zealand armed forces. A few months later the Bureau of Industry shut out competition from Thompson and Hills Ltd by refusing its application to enter the canning business in Hawkes Bay, thus guaranteeing monopoly status to Watties. Soon after this, the Government agreed to purchase another 500 tons of Watties’ produce for supply to the armed forces. In 1944 Watties was producing a huge quantity of goods on behalf of the Government in a new building paid for by taxpayers. By now the Government was reimbursing most of Watties’ expenses, including office and laboratory overheads, as well as depreciation. Moreover, if the Government wished to dispose of its assets, Watties had obtained the option to purchase at valuation – which, given that competition had been shut out – was bound to be a difficult calculation. The War Cabinet advanced another £10,000 to Watties in 1944 and paid a loss of £7,100 on the production of canned apples. That year, not surprisingly, Watties enjoyed record overall profits. James Wattie told shareholders that the war had brought about a demand for canned goods ‘not previously known’.57

The first indication that the Crown might wish to dispose of its Watties assets came in October 1944. The Government decided to sell the building it had paid for, and the figure of £9,000 was initially suggested by Treasury. Watties was in no hurry to respond; it had use of the building and was working on its own expansion plans. In August 1946 the company was obliged by its contract to exercise its option to buy the government plant. Treasury believed the building and machinery were now worth £12,000 and estimated that they would cost £15,000 to replace. The Ministry of Works thought the real value nearer to £40,000. Watties played hard to get. They paid off their remaining government loans, continued to use the State’s building, but refused to reach a settlement, although their production and profits were expanding at a fast clip. For a time Watties argued that they were not much interested in the plant, then made an offer of £7,000. Finally agreement was reached that they would pay £17,000 in cash, with interest payable from August 1946. Cabinet blessed the deal on 4 March 1948. Watties then pleaded a shortage of cash and persuaded Nash to grant them a State Advances loan. Treasury reluctantly agreed, suggesting an interest rate of 4.5 per cent per annum for prompt payment. Nash generously reduced this to 4.25 per cent. Nothing, it seemed, could be too good for wartime comrades.

Watties enjoyed their close relationship with the Government and came up with other ideas for concessions or direct help in the years ahead.58 Looking back, it is clear that officials and ministers played a significant part in developing this new, privately owned industry at a time when the market for canned goods could never have been better. Investors’ desires for profits, wartime requirements and the Government’s general ambition to stimulate an industry which employed many, especially in the marginally held seat of Hastings, happily coincided in an arrangement that was satisfactory to all. The taxpayer footed much of the bill.

No matter how lucrative the arrangements with the Government, many established manufacturers became wary of bureaucratic controls, preferring looser forms of cooperation within their various sector groups of the Manufacturers’ Federation. The National Party in opposition often complained about the growing mass of regulations. In October 1939 S. G. Holland, who was a loud backbencher and soon to be the party’s leader, called the Labour Government a ‘reckless crew of political “experimenters’”.59 For a long time the gravity of the war deafened people to such complaints. However, in 1943 Labour’s dirigiste economy began to overreach itself. The growing criticism was partly because a general election was on the horizon. But complaints to ministers about aspects of stabilisation were rising. The New Zealand Truth began a campaign against some of the regulations. On 11 August 1943 it stated forcefully that many were ‘bewildering to those who had to abide by them’ and required ‘an army of inspectors to enforce them’. Truth blamed the Government ‘for issuing regulations which reveal so blatantly that wishful thinking is the dominant note instead of commonsense’.60 Other complaints were on the increase; many manufacturers, for instance, were becoming restless about what they saw as an erosion of their margins compared with those of retailers.61 Envy and suspicion became constant handmaidens of bureaucratic intervention.

Labour narrowly survived the election on 25 September 1943. The Government lost eight seats – all of them in the North Island – and won only one new one, when Sir Apirana Ngata was defeated by an obscure Labour candidate in Eastern Maori. At 9.30 pm on election day, some of Fraser’s closest confidants thought ‘the ship was sunk’.62 But the arrival of the servicemen’s votes a few days later rescued several members, including the Minister of Health, A. H. Nordmeyer, and backbencher W. T. Anderton. The election result began turning ministers’ minds towards the postwar period and normalisation of the economy. What, however, was ‘normality’? Clearly it was not to be a world where the State pulled back from its active role in economic policy. Both politicians and bureaucrats intended to play a big part, using the experience gained in wartime. We can see the thinking of the men in Customhouse Quay from the draft of a speech they sent up to Sullivan for delivery to the Manufacturers’ Federation’s annual conference in October 1943. It argued for a policy of ‘planned and controlled trade and industry’ to sustain a ‘planned social system’.

The economic stability and progress upon which depends all future progress in social reform cannot be left to the chances of unaided individual enterprise in a world of promiscuous international competition. National policy must step in to secure for our producers a reasonable prospect of success, whether in supplying the needs of a balanced economic life at home, or in developing our export trade.

We are no longer what we once were, the overwhelmingly greatest and consequently cheapest producers in the world. That place is now occupied by the United States. On the other hand our standard of living and costs of production are far higher than those of many others who today are as fully equipped technically as we are. It is for the nation to use its powers of direction and guidance, of direct assistance, of the bargaining power of our rich home market, to secure favourable conditions from those who for economic and political reasons are most willing to cooperate with us and most need our cooperation.

Full of hubris, the draft speech looked forward to a world of plans and planners protecting New Zealanders from adverse overseas developments and guiding local business towards socially desirable ends.

It is conceivable that had Sullivan been a stronger minister, both intellectually and physically (he was often ill and had less than four years to live), the shape of the postwar economy might have been slightly different. However, while he could be irritable and moody, he happily complied with officials who were keen on planning, pointing out that he had first advocated this himself as far back as 1918. Years later, a journalist noted that Sullivan could have an audience believe ‘that every shirt or pair of shoes made in New Zealand was of tremendous quality even if it wasn’t’.63 In October 1943 Sullivan delivered his officials’ speech with gusto, noting that while there had been a ‘high degree of regimentation’ during the war, the Government had not socialised industry ‘nor does it intend to’. Assuring businessmen that it was not his intention ‘to irritate unnecessarily or to restrict wilfully’, he added: ‘Planning and control will be necessary after the war – planning to ensure continuity of production, and control to ensure equitable distribution…’64

Wartime experience and the unquestioning support of their minister gave officials at Industries and Commerce confidence that they knew what was best for the country. An experimental planning authority called the Organisation for National Development was established in 1944.65 It gave way to an Industrial Development Committee chaired by Sullivan but it did not survive as a stand-alone agency. It included representatives of manufacturers as well as the trade union movement, with officials from Industries and Commerce doing most of the work. The committee set out to cultivate industries that used New Zealand raw materials. Rope, twine, textiles, carpets, woollen goods, pulp and paper, dried milk products, chemicals and the canning of fruit and vegetables all caught the eyes of officialdom. ‘It is most desirable that efforts to develop New Zealand’s industrial economy should be directed first to those lines of production which are allied to our national resources and to our primary products’, said the department’s annual report. Sub-committees were already in place for the footwear, radio and electric ranges in addition to the still operational plans for flax, tobacco and the pharmacy industry.66 Yet, when Industries and Commerce was restructured, the Industrial Development Committee melded back into it. After November 1945 the department had two distinct units, one dealing with industry where planning was now located, the other with commerce. By this time Industries and Commerce which had employed 160 permanent officers in 1936 had 584 on its payroll – a growth trend that was shared by many other parts of the public service.67

Industries and Commerce was without a permanent head for several months in 1946. Like that of so many top officials, Schmitt’s health was causing trouble by the end of the war. He lessened his workload by moving sideways into the newly created position of Secretary of the Tourist and Publicity Department. His old job at Industries and Commerce was advertised. The top candidate was the former secretary, G. W. Clinkard, who had been with the Ministry of Supply in London for much of the war. Sullivan’s long-time distrust of Clinkard and his family connections led the minister to veto his appointment. After an interlude, P. B. Marshall, who had a background in the primary sector, was appointed secretary. However, Clinkard appealed to the Public Service Appeal Board and became Secretary of Industries and Commerce once more towards the end of 1946. A job had to be found for Marshall. He moved sideways into what soon became the lame duck position of Commissioner of Supply.68

Those with big ambitions for industry were firmly in control once more. Clinkard was soon busily at work establishing eleven commodity sections within the department, each with a controlling officer who was to exercise suzerainty over a huge list of manufactured items. A most ambitious Industries and Commerce Bill was drafted for introduction. It planned to give the department virtually complete power to control industrial development in New Zealand in any manner that the minister or bureaucrats believed to be in the public interest.69 Fortuitously, perhaps, Dan Sullivan died on 8 April 1947. Some weeks later, on 29 May, the able 46-year-old Arnold Nordmeyer, who had been Minister of Health since 1941, took the portfolio of Industries and Commerce. Shrewder than Sullivan, sharing none of his antipathies and less prone to being swept along by his officials’ ideas (he did not proceed with Clinkard’s bill), Nordmeyer nonetheless found himself enmeshed in the web of controls and schemes that had been spun during twelve years of continuing governmental experimentation.

While officials were nurturing plans and juggling jobs, Walter Nash realised as early as the middle of 1944 that some wartime controls were becoming a needless irritant. In July Nash commissioned a review of all 243 sets of regulations that had been gazetted since the beginning of the war. A short list of those deemed unnecessary was produced, but officials also tendered several more pages of regulations that would be needed after the war, and a further 54 that ought to be converted into permanent legislation.70 The rules covering the Arbitration Court were relaxed slightly, and early in 1945 rigid wage stabilisation was slightly modified. In March there was a small wage rise. Concerns were growing about the application of import licensing. Early in 1945 the Factory Controller, G. A. Pascoe, told Nash that the Industries Committee deciding import licensing priorities was ‘exercising an influence over manufacturing units far beyond what could have been contemplated’. The ‘insidious’ influence of officials was interfering ‘most unusually’ in the internal distribution of limited raw materials. According to Pascoe, officials were simply too busy to do the work expected of them, and some businessmen were suffering adversely from arbitrary decisions. He recommended that the committee be reconstituted with new terms of reference. The Manufacturers’ Federation wanted a Trade Control Commission to handle import licensing and tariffs, and was urging the introduction of flexible policies as well as lower taxes.71

It is not clear how much notice was taken of these pieces of advice. The role of the advisory group now known as the Industries Committee was constantly under scrutiny, with its own members unhappy about its precise interface with the Customs Department that issued import licences. In 1946 the committee was renamed the Executive Advisory Committee to the Commissioner of Supply. Various pressures kept impinging on its work. No strict procedure was adhered to for awarding import licences; ministers themselves often intervened when constituents or interest groups sought to bypass what were said to be proper channels. Moreover, it was clear that import licences were being sold by those lucky enough to have secured them, a practice which inevitably added to a manufacturer’s costs. There were constant crosscurrents within Industries and Commerce. Pascoe thought the proliferation of ‘backyard’ industries was costly to the economy, noting in a memorandum to Nordmeyer that they often made goods ‘which normally could be much more economically imported without jeopardising full employment’.72

Some experiments, such as ‘austerity clothing’, obviously had to be dealt with. On 20 April 1945 the Dominion reported a retailer as saying that the ‘the public is sick and tired of austerity goods’.73 In May the Factory Controller was instructed to cancel the rules as soon as possible. They were withdrawn later that month and pending prosecutions against manufacturers who had failed to comply were abandoned.74 A slow, general process of deregulation was soon under way after VE Day on 8 May 1945. Manpower controls were gradually lifted. They had mostly gone by November. By the end of the year 133 sets of Emergency Regulations had also been lifted.

However, in line with officials’ earlier recommendations, 362 sets of regulations were retained, and an Emergency Regulations Amendment Bill was passed in December 1945 to keep those deemed essential to postwar planning in place for one more year. The Act was then extended in 1946 and again in 1947, despite mounting criticism from Holland, the National Party’s leader, who described the re-enactments as having ‘all the elements of a communist system, of totalitarianism and dictatorship’ because they enabled regulations to be enforced without parliamentary consent.75 Eventually the Government passed the Economic Stabilisation Act in November 1948. It placed many of the wide powers that ministers had been using for some years into statutory form.76 A select committee chaired by Clyde Carr, MP for Timaru, worked steadily through remaining regulations and cautiously approved occasional further revocations. The Standards Institute remained and issued recommendations about standards for garment manufacturing and other industries for many years to come. As in 1914-19, wartime authoritarianism spilled over into domestic issues like education, broadcasting and liquor. In a tone of disappointment, the former Labour MP Ormond Wilson observed later that ‘one of the inherent tendencies of bureaucracies is the enforcement of conformity’.77 In a manner reminiscent of World War I, school curricula were carefully monitored and uniforms enforced at all state secondary schools. The internal struggle within the Labour Party that resulted in the expulsion of John A. Lee, the flamboyant MP for Grey Lynn, was part of the Government’s striving for conformity. Refused a position in Cabinet in 1935, Lee increasingly marginalised himself within the Labour caucus with policy criticisms that took on a more personal tone as Savage’s health deteriorated. Worried by the inflationary implications of Lee’s constant advocacy of more Reserve Bank credit, and discomfited by the occasional inference that foreign loans could be dishonoured, ministers came to detest Lee, seeing him both as a threat to their concept of insulation as well as their hegemony within caucus. Playing on wartime fears, and holding Savage’s illness in part against Lee, the combined forces of the parliamentary Labour Party and the union-dominated Central Executive of the Labour Party succeeded in expelling him from the party at its annual conference in March 1940. Only the Speaker, W. E. Barnard, and a few party officials went with Lee, although, as several historians have shown, Lee’s departure had more serious consequences at the party’s grassroots. However, Lee’s efforts to launch a new party, the Democratic Labour (later Soldier Labour) Party, came to little. He faded from the scene, his name becoming a synonym for disloyalty and maverick economics. His expulsion was a victory of sorts for the leadership of the Labour Party and for their narrower, less experimental vision of the country’s future.78

Developments within broadcasting are another pointer to Labour’s desire for tight social control. State interest in this medium had been growing since 1921 when the first provisional permits were issued by the Post and Telegraph Department for transmission and reception. After 1925 private broadcasting was in the hands of a state-sanctioned monopoly run by William Goodfellow and Ambrose Harris. This monopoly came to an end in 1931. It was not ideological consideration so much as public discontent at the limited array of programmes and pressure from some university educators wanting a higher level of educational content, that led Forbes’s Government to set up a National Broadcasting Service to be run by a ministerially appointed board.79 A ‘raggle-taggle army of local outfits’ broadcast privately owned, regionally sponsored commercial programmes under fairly strict state regulations administered by the NBS.80

Labour leaders were uneasy about a state-run broadcasting system so long as they did not hold the reins of power. Their discomfort was heightened by ministerial interference with a pro-Labour ‘Friendly Road’ broadcast by a charismatic radio parson, Colin Scrimgeour, on the eve of the 1935 election.81 Once in office, Labour’s opposition to a state system faded. The Broadcasting Act which passed on 11 June 1936 required all broadcasting to be in public hands. It abolished the Broadcasting Board and commissioned the Minister of Broadcasting (the Prime Minister) to produce a national service.82 On 8 June 1936 the Prime Minister declared that the Government was ‘going to be master of publicity. We are not going to wait for the newspapers or the Opposition to tell the people what we are doing. We are going right ahead. That is plain, is it not?’ He added that the deliberations of Parliament would be broadcast direct to the people.83 It was axiomatic to the reformer’s mind that, once apprised of the details of what Labour had in store for them, the wider public would be bound to approve.

Newspapers and Opposition politicians howled at the prospect of a state-run broadcasting service falling into the clutches of Labour ministers, especially when Clyde Carr MP attacked ‘the biased press’ during the debates, and declared that the Government intended to ‘cut the claws of this monster’.84 However, with broadcasting, as in so many things, cautious action followed bold words. Savage told the Standard that he wanted to see broadcasting conducted ‘on proper lines’ and was seeking a ‘topnotcher’ to head it.85 On 1 December 1936 Professor James Shelley of Canterbury University College, whose W.E.A. courses in the 1920s had always appealed to Holland, Fraser and Nash, became Director of the National Broadcasting Service. By the end of 1936 a large new building was being constructed for 2YA. A giant radio mast rose above Titahi Bay.

Shelley wove his way skilfully through the petty jealousies within the new medium. He set basic standards for regional stations, while allowing them considerable autonomy. He and Heenan played a major role in stimulating the arts. From 1947 until 1988 annual broadcasting fees subsidised a symphony orchestra. However, like the New Zealand Listener, which began in June 1939 with Oliver Duff as its editor, the National Broadcasting Service in its early days was a fairly conservative institution, not too highbrow, cautious of its political masters, and reluctant ever to shock the public. Some thought it reliably dull and run by a killjoy.86

Commercial broadcasting was a bird of different feather. Here the Government had a more overtly political goal, as Savage explained. ‘This modern medium of communication has become one of the outstanding features of economic and social life’, he told a Standard reporter in November 1936. ‘Its social value has, as yet, hardly been realised…. Radio has proved to be the most powerful force for propaganda devised….’ Savage promised not to misuse radio, but stressed its value to businessmen who needed the ‘latest medium of publicity’ to advertise their New Zealand-made goods. As Prime Minister, he wanted to see ‘truthful and reliable advertising of good products’, a role which Daisy Basham, better known as ‘Aunt Daisy’, performed with gusto on commercial radio for a quarter of a century.87 Constant advertising of New Zealand-made goods was an essential ingredient of Savage’s self-dependent, insulated society.

However, ‘Uncle Scrim’, as he was widely known, was much more difficult to deal with than Shelley. The parson was as flashy as the professor was grey. Scrimgeour drove a hard bargain with ministers when the new Act obliged the Government to purchase his small, failing Auckland commercial station. He emerged as Controller of Commercial Broadcasting, while many of his former staff operated initially from the station’s headquarters in Queen’s Arcade, Auckland.88 Scrimgeour was less prepared to tolerate political interference with programming and when Kenneth Melvin’s ‘History Behind the Headlines’ day-to-day account of international events from Europe was suppressed in 1939, he let irate listeners know who was responsible.89 When Savage, who was Scrimgeour’s sole ministerial patron, died, government antagonism became more obvious. Scrim’s radio eulogies of John A. Lee after his expulsion from the Labour Party angered Fraser. After a number of further transgressions, Scrim was called up for military service in an obvious move to silence him. In 1943 he was sacked. He stood against Fraser in the 1943 election where he scored 15 per cent of the vote in Wellington Central and cut a large hole in the Prime Minister’s majority.90 But it was Shelley’s caution that prevailed in Broadcasting House when the National and Commercial arms were eventually combined. The Labour Government preferred it that way.

Expressions of dissent in films and magazines also worried the ministry. On the outbreak of war Heenan recalled a number of anti-war films. All Quiet on the Western Front, The Road Back, They Gave Him a Gun, Three Comrades, Dawn Patrol, The First World War and Shopworn Angel were all believed to depict the horrors of war sufficiently realistically to impede recruiting campaigns.91 An old Labour stalwart, J. T. Paul, was appointed Director of Publicity a few weeks later. He was responsible to the Prime Minister. Between them they ran ‘a formidable system of censorship and of control over public expression of opinion’.92 Tomorrow magazine soon ran into trouble. After the 1938 election it continued to espouse the declared goals of the Labour Government but was critical of aspects of economic policy and opposed the move toward conscription, which was eventually introduced in the middle of 1940. It criticised the so-called ‘phoney war’ in Europe and carried an article by Lee that was critical of Savage. In the tense days surrounding the fall of France and the surrender of Belgium this was too much. Paul complained to Fraser; the Attorney General, Rex Mason, labelled some of the articles ‘subversive’. The Superintendent of Police called on the printer of Tomorrow and its last issue appeared on 29 May 1940. Everywhere social engineers, particularly those striving to safeguard their domestic achievements in a time of war, found it necessary to be authoritarian.

The concept of trust control of liquor which developed in 1943-44, and which has survived for half a century, was rooted in the notion that there was a need for public authorities to tighten control over the distribution of alcohol. Throughout Labour’s history, liquor had always been an issue dividing friends. Savage had worked for a brewery; Fraser drank little or nothing; Nash, when he drank, did so privately. Labour MP’s always insisted that issues concerning alcohol were conscience issues in Parliament and not subject to the whip. When more than 60 per cent of the voters in the Invercargill Licensing District voted at the 1943 election to restore liquor sales to their area, the issue of what form this should take landed on Cabinet’s plate. Nash sought advice from his officials on whether the State or the local municipality should run the new liquor outlets in Invercargill. Ashwin was not enthusiastic about municipal control. He tended to favour state control because uniform standards would be easier to maintain. Others supported this view, arguing that a state monopoly would remove competition from the liquor trade. Competition was seen to be the cause of so much that was bad about the sale and consumption of alcohol.93

However, locals in Invercargill preferred that key decisions remain with the locals. They set up an Invercargill Municipal Control and Ownership of Licensed Hotels Committee.94 Invercargill was a marginal seat and Cabinet agreed to the concept of a locally elected committee to establish and run hotels. The community would benefit from the distribution of any profits. The Invercargill Licensing Trust Act passed on 29 March 1944 and the Government soon lent the trust £50,000 to establish outlets in the area. A Treasury official assured the minister that the advance would be secure: ‘With the trust exercising a monopoly and not having to pay anything for goodwill, it would only be through the most careless mismanagement that the trust would encounter financial difficulties’.95

In June 1944 Cabinet agreed to guarantee further trust borrowing from the Bank of New Zealand to a limit of £200,000. The trust was required to pay tax at a rate of 70 per cent on its profits, which left little for capital development, let alone distribution to the community. Nonetheless, the Trust Board pushed ahead with an ambitious building programme and by April 1947 had a total overdraft with the BNZ of £267,579. The Justice Department was now responsible for overseeing the trust and was not happy with the quality of decision-making. One of its officials told Ashwin that he doubted whether private enterprise would have constructed so many outlets, noting that the potential bar business at two hotels ‘is insufficient to justify the capitalisation involved’. He continued: ‘It must not be overlooked … that none of the members of the Trust has any experience of hotel management or the liquor trade, indeed, few have any business experience.’96

This lack of business and financial skills remained a problem for the growing number of trusts – there were 14 in existence by the middle 1970s. When licence restoration carried at a general election the public until the mid 1990s opted to support a trust at the ensuing poll. People believed that the local community, rather than the ‘liquor interests’, would benefit from profits. However, some trust boards made careless decisions and several have been able to survive only because of the monopoly status they enjoy in their area. The profits distributed locally were, for the most part, small.97

Once wartime powers were assumed, they were seldom surrendered lightly anywhere in the world. In New Zealand they became entangled in postwar policy formation to such an extent that the transition was virtually seamless. In their determination to ensure there was no repeat of the economic upheaval at the end of World War I, Peter Fraser’s ministers developed an elaborate programme for rehabilitation for the 224,000 people who served during the war. If it was to be successful, rehabilitation required a continuation of the legislative and regulatory underpinning found so useful during the war. It was to be a repeat, this time on a grander scale, of the State’s contractual obligations to early settlers who had been led to believe they would be looked after.

Demobilisation was handled cautiously; the peak months were from June 1945 to May 1946.98 At the point of discharge, service personnel received a gratuity of 2s 6d for every day spent overseas and 8d per day for service in New Zealand. The money was paid into a Post Office Savings Bank account and received a 5 per cent bonus each 31 March on the sum remaining in the account. Nearly £23 million was paid out in gratuities. A National Employment Service assisted service personnel in finding civilian employment. This was no onerous task because of the buoyant state of the labour market. A Rehabilitation Department had been set up in November 1943 under the Rehabilitation Act passed two years earlier. Through a variety of assistance schemes involving trade-training (11,000 returnees received assistance), university bursaries and general educational assistance (27,000 beneficiaries), land settlement schemes (12,500 were settled), business (11,500 were granted loans) and housing and furniture loans (a total of 64,000 were granted, while another 18,000 returnees were allocated state houses), service personnel were eased back into normal lives. In all, a total of £264 million was advanced to them, much of it (£192 million) in loans. The cost of administration was barely 2 per cent of the total paid out.99 It is generally agreed that rehabilitation went much more smoothly in 1945 than it had in 1919, due to the foresight of officials and the skilled administration of the minister, C. F.(Gerry) Skinner MC, himself a recently returned war hero. But there can be no doubt that the absence of unemployment during the next twenty years did more than anything else to ensure success.

Expanding health services; a district nurse checks a Maori baby’s progress on the Waihara gumfields, late 1940s. ATL F-46725-1/2

However, in the postwar world Fraser’s Government left little to chance. Public Works projects, especially hydro-electrical construction, were given high priority as the Ministry of Works struggled to satisfy escalating demand for electricity. By March 1949 there were 5000 more workers employed on state projects than there had been in 1944. Treasury warned the Minister of Finance about overheating the economy.100 The Government pushed ahead, although it realised that continuing controls would be necessary if it was to survive at the ballot box.

The twin goals of maintaining full employment and spending more on welfare at a time when so many service personnel were coming back into the community with pent-up ambitions to spend their record savings-bank deposits,101 threatened a huge increase in demand for imports. Shortages of raw materials and finished products compounded the problem. Faced with runaway inflation or tight controls, Labour passed a Control of Prices Act in November 1947. It put the Price Tribunal into statute for the first time, and outlined its regulatory powers.102 More subsidies were introduced to restrain retail prices. Sugar, wheat, bread, butter, cheese, milk, eggs, oatmeal, phosphates, cornsacks, many fertilisers, fertiliser bags, cow covers, and the transport by road and sea of timber and fertilisers were now subsidised. Various payments were made for the eradication of noxious weeds and rabbits and for the testing of cows. When Ashwin reported to his minister in February 1947 that subsidies were running at £800,000 above budget, and were certain to cost an extra £4 million for the year 1947-48, Nash asked Leicester Webb, the Director of Stabilisation, to conduct a study of the likely costs of removing subsidies altogether.103 The reply made dismal reading; they were now economic woof and warp. The Government tentatively removed some farming subsidies as well as those on tea and sugar. Rail and shipping charges were allowed to rise. The following year, with an election on the horizon Nash increased subsidies once more. Their cost reached £14.6 million for the financial year 1949-50.104

Government subsidies and special grants became such an integral part of postwar stabilisation that most people came to believe they had a right to them. In 1947 Fraser received a request from the Canterbury Cricket Association for subsidies on their purchases of bats, balls and clothing,105 while a group of Motueka tobacco growers testily informed the Tobacco Board in November that they took ‘strong exception on principle’ to the notion that they might contribute to the cost of flood protection work in their area. Local authorities ‘have an obligation’ to do the work, ‘and the Government has a greater obligation to supply the finance’.106 The incoming Minister of Finance, S. G. Holland, observed in his budget in August 1950 that ‘many people have a fallacious idea that what the State provides does not cost them anything’.107