New Zealanders spent the years from 1949 to 1984 trying to keep Labour’s welfare state operational. By 1950 the State was spending nearly 30 per cent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product each year. In a country of 2 million people, the public service employed 30,000, and another 85,000 were directly or indirectly being paid by the State.1 The State’s payroll, its ambitious capital works programme, and the policies of various state trading enterprises enabled it to play a major role in the economy.2 The private sector was dominated by the processing and marketing of agricultural production; yet only 20 per cent of the total workforce was now involved in farming and related activities which produced approximately 85 per cent of New Zealand’s overseas earnings. The major export lines – meat, wool and dairy products – were handled by a variety of public agencies, and most went to one market, the United Kingdom.

Manufacturing had developed rapidly since 1935. It now employed 25 per cent of the work force, a high proportion of them in small production units that thrived behind the protective fences of import controls and tariffs. More than 62 per cent of New Zealand’s factories had ten or fewer workers.3 Their output was almost entirely for domestic consumption. Small production runs inflated costs. The State registered all industries. It lent money to many, subsidised some items that featured on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and through a variety of mechanisms influenced most aspects of the marketplace in which they traded.

The application of price control to most goods in the CPI, and to others not in it, operated on a ‘cost-plus’ basis. Manufacturers provided the Price Tribunal with figures detailing their costs and on top of these an allowance was made for ‘reasonable profit’. Since there was a constant shortage of workers (Holland estimated there were 33,000 vacant jobs in October 1951), labour costs rose steadily. The gap between the Arbitration Court’s average award wages and the actual sum paid to workers widened. More work was done at overtime rates too. These costs were passed on to the consumer. Work habits, as the 1952 report of the Royal Commission into the Waterfront Industry showed, were deteriorating in some areas. A booklet published by the Department of Internal Affairs in July 1952 noted that New Zealand life moved at a slower pace than in many European countries, and that ‘there is not quite the same struggle for existence….’ Ten years later the Monetary and Economic Council referred to ‘an attitude of relaxed ease’ among the workforce. Theft from workplaces was not uncommon, the price of such ‘perks’ being added to overheads and ultimately passed on to the consumer. Since there was little domestic competition in the production of many items, and import licensing prevented similar goods entering the New Zealand market from abroad, ‘cost plus’ was virtually a licence to make money at the consumer’s expense.4

New Zealand had developed an economy where there was no unemployment, but the cost structure rose steadily. And so did tax rates. As the Government’s advisers often pointed out, escalating taxes were a disincentive to private investment and enterprise. A ministerial committee on taxation reform headed by a Christchurch accountant, T. N. Gibbs, was established in 1950. It was the first such inquiry since 1924. Gibbs’s review of developments during the intervening period noted that the tax take, which constituted 14 per cent of national income in 1925-26, had doubled to 28 per cent by 1949-50. The top marginal tax rate in 1950 remained at 77.5 per cent, the same as it had been at the end of the war. Whereas the percentage of tax revenue spent on social services amounted to 5.9 per cent in 1925-26, it was now 15.3 per cent. Health, education and monetary transfers to those deemed deserving had risen ninefold in the intervening 25 years. In a cautionary note that was similar to warnings that Ashwin had been giving to Nash, Gibbs concluded:

There has been established by the welfare programme a series of commitments that appear rigid and difficult to modify. These commitments can be supported only by a continuous expansion of the national economy, which must come from a real increase in volume of production and not merely from increases in values … through continuing inflation. If the economy does not expand, the welfare programme will be endangered both from yields from taxation and the probable increase in claims on the fund.

Under the combined burdens of high protection, rising labour costs, poorer standards of work and high taxation by world standards, it was not long before the country’s economic growth rate subsided; in 1962 a report from the Monetary and Economic Council noted that between 1949 and 1961 the New Zealand economy ‘has earned the unfortunate distinction of having one of the slowest annual rates of growth of productivity among all the advanced countries of the world’.5 The viability of Savage’s insulated economy was under threat.

Gibbs’s warning about the vulnerability of New Zealand’s welfare state went virtually unnoticed at the time. Generations came to believe that governments could allocate resources more successfully than the market and that centrally driven economic intervention was for the wider public good. Grandparents who had lived through two world wars and a depression welcomed the security of pensions and health care in their twilight years; parents expected that the State would help with housing, educate their children from birth to tertiary level, provide them with low-cost health care and, through a network of tariffs and other regulatory mechanisms, ensure that full employment continued. Children grew up in what Savage once called a ‘cradle to grave’ system, something that more sceptical Americans labelled ‘womb to tomb socialism’.

It was an intimate society, where staff appointments to schools and university exam results were reported in the newspapers, along with traffic fines and art union winners. It was also a world of strict social controls. The tight restrictions of the Shops and Offices Act 1936, which was amended in 1955 (it changed little in practice), limited shop trading hours. Shops were closed over long weekends. Sunday shopping was prohibited and considerable controversy surrounded any application by retailers’ associations to trade on Saturdays. Late opening on Fridays was common. Dairies could sell ‘exempted goods’ over a weekend but everything else had to be locked away out of view. From the late 1940s until the Shop Trading Hours Amendment Act of 1980, Saturday trading was prohibited in most awards. Broadcasting remained firmly in the State’s hands and this monopoly was unchallenged until a pirate radio station began broadcasting from a ship in the Hauraki Gulf in December 1966. The state-owned Listener followed a cautiously conservative line on most things. Cinema prices were regulated by the Government, while the films themselves were censored by a branch of the Department of Internal Affairs. Its head, Gordon Mirams, strove to exclude, or at least to cut severely, those depicting violence and sex. When offered the option of 10 o’clock hotel closing or a continuation of the ‘6 o’clock swill’ in a referendum on 9 March 1949, the public stuck with the status quo. Only with betting on horses was there any willingness to strike out in a new direction; voters supported the introduction of off-course totalisator betting by a wide margin.6 For the most part the insulated economy operated in a tightly controlled social environment, one with floors, ceilings and heavy curtains.

At mid-century the centralising forces within New Zealand were at their peak. The powers of Cabinet government increased steadily. While the upper house known as the Legislative Council had never been a robust institution, it faded in public esteem after the failure of bills to reform it at the time of World War I. As the years passed, the upper house became little more than a rubber stamp for decisions of the House of Representatives. The new National Government in 1950 fulfilled its promise to abolish the council and met with little opposition. Henceforth, the legislative process became even swifter, the Governor-General’s assent to bills often being given within hours of their passage through the now unicameral parliament. A later prime minister was to label New Zealand ‘the fastest lawmaker in the west’ and to title a book on the subject Unbridled Power. Government by regulation was commonplace; few bills were without regulatory powers and each year several volumes of regulations were promulgated by the Executive Council, which usually met after Cabinet each week with the Governor-General presiding.7

Governments performed balancing acts, endeavouring always to deliver as much as possible in the least intrusive manner because they realised that the public appetite for wartime regimentation was abating. Some freeing up of the economy was both wanted by interest groups and promised by the National Party in 1949. However, many anomalies resulted from tentative moves in the 1950s and 1960s to ease back on economic and social controls. Continuing high taxes, escalating government expenditure, declining national economic performance and an increasingly difficult world trade scene eventually exhausted Labour’s legacy.

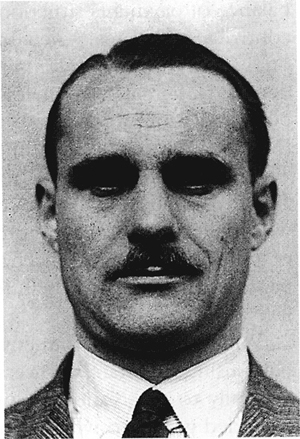

The National Government led by Sidney George Holland took office on 13 December 1949. Aged 57, with a face that was ‘all hills and hollows’, the new prime minister appointed himself Minister of Finance. He held this position until after the election of 1954. Holland had a Christchurch background in small business and accounting. He had been the only new face on the Coalition benches after the 1935 election and rose rapidly to leadership of the Opposition in November 1940. John Marshall, who was a junior minister in the new Government, later described Holland as a ‘vigorous, buoyant, positive personality …. an ordinary man with …. an air of confidence’. He had a powerful voice and great stamina. But Holland was not an ideas man; his political philosophy could, according to Marshall, ‘be written on the back of an envelope’.8

Like the Labour Government of 1935, neither the new prime minister nor any of his ministers had held office before. Only one of the departmental heads with whom the new ministry was dealing had experience as a permanent head under anything other than a Labour Government. In the opinion of one senior Treasury official at the time of the change, most public servants felt comfortable with the command economy.9 What made Holland’s position more difficult than Savage’s was that the intellectual climate in which National was operating was much less congenial to change than Savage had experienced. In 1936 collectivism was well on the way to its zenith worldwide; it still commanded a wide following in the 1950s. There were regular press comments lauding developments in Russia,10 and the counter-attack against collectivism led initially by Friedrich Hayek and later by the Chicago School of Economics was only in its infancy. Jack Marshall had read Hayek’s Road to Serfdom and espoused ‘liberalism’ in his maiden speech.11 The Minister of Education, Ronald Algie, had been Professor of Law at Auckland University College after which he edited the National Party’s periodical, Freedom. Clifton Webb, the Attorney General, W. J. Broadfoot (Postmaster-General) and W. A. Bodkin (Internal Affairs) were small-town solicitors, while Frederick Doidge (External Affairs) had some knowledge of the wider world, having been a Fleet Street journalist. The new Minister of Health and, from December 1950, Industries and Commerce as well, was Jack Watts. He was a Christchurch lawyer who had done well at university. Few others seem to have read much, although Keith Holyoake, the Deputy Prime Minister, endeavoured to keep up with books about New Zealand’s politics and history.12 Most ministers had farming or small-town backgrounds and were instinctively suspicious of big government, especially when, to their minds, it had been overly concerned with promoting full employment in the cities by methods that pushed up farmers’ costs.

Changing the guard on 13 December 1949: Peter Fraser hands over to Sidney George Holland. ATL F-75156-1/2

At first, Holland’s ministers and their officials circled each other uneasily. Some Treasury officials hoped for more disciplined expenditure, but other bureaucrats simply criticised the intellectual capabilities of their new masters. Requests that officials reduce the length of complex memoranda raised eyebrows.13 While the declared policies of the governing party changed after December 1949, putting them into practice proved more difficult and over the next few years the new Government was largely deflected from its purpose, settling instead for the rhetoric of freedom while it administered most of the regulations and controls inherited from Labour.

With encouragement from Ashwin, Holland set out early in 1950 to wind back the State. Land sales were freed from control in February, which led to an immediate increase in the number of rural properties on the market. Many building controls were removed, which caused an upsurge in construction. Early in March the Government lifted some exchange controls.14 Ashwin had told Nash that Labour’s decision to pump £32.6 million of Reserve Bank credit into the economy in 1949, mainly to promote a huge capital works programme, was inflationary.15 He repeated this message to the new Prime Minister in December 1949 and again in March 1950, telling him that inflation was being ‘fed and perpetuated’ by ‘too high a level of State expenditure’. The Government’s subsidy regime was exceeding budget, while the revenue side of the next financial statement would be £15 million less than necessary unless remedial action was taken. By this time wheat flour and bread subsidies were costing nearly £4 million per annum, butter and milk £2.4 million each, coal £2.3 million, tea £1.4 million, wool £1.4 million and railway losses another £1.5 million. Ashwin recommended reducing subsidies by a total of £12 million, and allowing the State’s trading enterprises to charge more for their services:

In my opinion the Government would be unwise to attempt to scramble out of immediate difficulties by tinkering with the problem which in that case would still be facing them next year, perhaps more aggravated…. While the action proposed is drastic … it is a necessary step in achieving financial stability, and it is better to get it all over in one operation than to have to chip at it in successive years.16

The changes would come at a cost; Ashwin pointed out that saving £12 million in subsidies was likely to result in an increase of more than 6 per cent in the CPI.17

Holland took the risk. On 5 May 1950 he broadcast to the nation that he was cutting subsidies by £12 million. Butter, bread, flour, eggs, gas, milk, telephones and railway fares would all increase in price; butter rationing would cease and subsidies on tea, coal and wool were to be removed altogether. In a highly political statement which accused the former Labour Government of hugely increasing its use of Reserve Bank credit in its last year of office, Holland described inflation as the biggest problem facing New Zealand. He described it as ‘remorseless and relentless’, ‘the cruellest enemy of the working man’s pay envelope’, something which ‘worked day and night’ and ‘underground’. Despite Ashwin’s estimate, Holland claimed that the changes he was announcing would add only 4 per cent to the CPI.18 In order to minimise the impact of these price rises on the most vulnerable sections of society, many social security benefits were increased from 8 May.

Cabinet went further. While vigorously reaffirming their intention to maintain full employment and stabilisation, ministers nonetheless abolished Labour’s Economic Stabilisation Commission. Members received letters thanking them for their services on 22 May 1950.19 In his budget speech in August, Holland spoke of selling some state assets and nominated the National Airways Corporation as a likely contender. A royal commission was soon empanelled to look into the growing debts of the New Zealand Government Railways and there was talk of closing some branch lines that were not paying their way.20 Holland promised less development work by the Ministry of Works, suggesting that local authorities should shoulder more responsibility.21

National had campaigned with the slogan ‘Own Your Own’ and candidates talked of ‘a property-owning democracy’. The new Government set about encouraging more private house construction and scaled down the number of state houses being built. Tenants of state houses were given the option to buy. Holland gave a ringing declaration of National’s philosophy in his 1951 budget:

The Government believes that New Zealanders are at their best when they are freed from direction and interference of the State; that they work hardest when incentives are provided; that private ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange is best for people; that most people have an inherent desire to own things, especially the homes in which they live and raise their families; that an abundant supply of goods is the best system of price control yet devised; that the average New Zealander is inherently honest and trustworthy, and that black marketing and such like devices only arise when normal liberties and freedoms are interfered with.22

However, it was not long before the National Government, its sails billowing with talk of private enterprise, was virtually becalmed. While many newspapers praised Holland’s announcements and the Wellington Chamber of Commerce saw the subsidy reductions as ‘a real step forward’, the price increases they caused were soon exacerbated by inflationary pressures flowing in from abroad as a result of the West’s general rearmament programme and the outbreak of war in Korea. Earlier in the year Peter Fraser had described Labour’s subsidy regime as ‘sound and socially just’ and in the interests of ‘the family man’; Holland’s speech of 5 May he labelled ‘a depression utterance’. Other Labour spokesmen portrayed subsidy reductions as a return to ‘an uncaring world’.23 An angry deputation of union leaders met Holland on 23 June 1950, claiming that the Arbitration Court’s recent interim wage order would not fully restore workers’ standards of living. A few weeks earlier, several of the more militant unions had walked out of the FOL and set up a rival body, the Trades Union Congress. There followed many months of intense rivalry between the two groups, as the TUC, in particular, tried to impress unionists everywhere with the gains it intended to make from the use of militant tactics. There were skirmishes on the waterfront between May and September 1950; Jock Barnes and the New Zealand Waterfront Workers’ Union sought more freedom from tight wage restraints. Barnes’s quest proved to be a lonely, and ultimately disastrous, mission.24

Members of the new waterfront union being trucked on to the Auckland waterfront by the army, May 1951. Auckland Star

The Government quickly came under pressure from employers and the National Party’s own ranks to take a tough line with union militants. Many harboured a visceral detestation of ‘wharfies’. The Korean War produced calls once more for wartime sacrifices and the Government toned down its talk of ‘economic freedom’. Inflation was running at 10 per cent by the end of 1950, and it rose to 12 per cent in 1951.25 Receipts for wool reached such an all-time high that the Government moved to dampen the inflationary impact by retaining a total of £51 million in two Wool Retention Accounts.26 Nor would it release all goods and services listed in the CPI from price control. At the end of 1950 at least two thirds of them were still controlled.27 Given the rapid rate of inflation and the immediate political threats it posed to standards of living, National’s ministers were starting to warm to the regulated economy.

What finally converted Holland’s Government to controls was the waterfront dispute that lasted for 151 days between February and July 1951. A complex dispute over wages in February led the union to apply pressure to employers by refusing to work overtime at all ports. When Barnes insisted on direct bargaining with port employers and would not accept the findings of an independent arbitrator, the wages system that had existed for many years was imperilled. On 16 February the Acting Prime Minister, Keith Holyoake, gave the watersiders an ultimatum to return to full work and submit their case to arbitration, or face removal of their conditions of employment. To reinforce this ultimatum, Holland on his way back to Wellington observed with inflammatory rhetoric: ‘Any individual or group of individuals who stands in the way of the country’s preparations for defence to ensure peace … by limiting the handling of goods is a traitor, and should be treated accordingly.’28 This was a very strong hint that the Government intended to get tough with any workers who attempted to break out from the controlled economy. Barnes did not heed the warning. Over the next ten days, commission control was removed from the waterfront, a State of Emergency was declared under the Public Safety Conservation Act 1932, drastic Emergency Regulations giving the Government wide powers were gazetted and the New Zealand Waterside Workers’ Union was deregistered. Troops began working ships on 27 February. The Auckland Star’s editor smugly wrote: ‘The Government now has an opportunity to teach the leaders of the waterside workers’ union and all who follow them so submissively a lesson that is more than overdue.’29

Holland and his forceful Minister of Labour, William Sullivan, used every power they had inherited from the wartime government, including press censorship and the opening of mail, and a great deal of red-blooded rhetoric, to smash the watersiders’ national union and nip in the bud any union efforts to operate outside the confines of compulsory arbitration. The watersiders and their dwindling allies responded with several acts of sabotage and a good deal of victimisation of those who disliked Barnes’s quest for martyrdom and wanted to return to work. As tempers frayed, the Government also backed the Labour Opposition into a difficult corner, extracting from its new leader, Walter Nash, the comment that ‘we are not for the watersiders, nor are we against them’.30 Riding high with the public, and with the Federation of Labour and every newspaper in the country behind his efforts to humble the ‘wharfies’, Holland could not resist the temptation to cash in politically. The five-month crisis had been a welcome diversion from inflation and the perceptions that had been building up that government policy was feeding it. On 1 September 1951 the National Party secured another three years in office, winning four more seats (all of them port electorates) from Labour.31 In the weeks that followed, the Government tightened up the I.C.&A. Act and inserted several draconian clauses into the Police Offences Act, including one establishing a crime of ‘seditious intention’. The Government sought to make all forms of direct action illegal. The National Party was indulging itself.

The TUC collapsed and there was a marked fall-off in union militancy for the next few years. But most political victories have their costs. The Government triumphed over a section of the trade union movement that National supporters most detested at the price of virtually ceasing its attempts at macroeconomic reform. Having preached the need for retaining controls over wages during the dispute, the ministry was soon being badgered by workers, whose incomes were under tight restraint, to return to rigid price control. Holland agreed during the 1951 election campaign to an increase in subsidy payments on butter, bread, flour and gas. In October that year Cabinet further extended subsidies to soap makers. Hides, pelts and bobby calf skins were soon added to the subsidy list because of the flow-on effect of high world prices on domestically made shoes. Some of the money for the subsidies came from the Meat Pool Account.32 These payments were in addition to the taxpayer-funded subsidies on other items. Collectively, subsidies were soon costing £14 million per annum.

Fiddling with subsidies in order to restrain retail prices became a regular feature of Holland’s administration. But the constant changes met resistance from some. A large and grumpy deputation from farmers’ organisations complained to the Prime Minister on 31 May 1951 that using some of the surplus from the Meat Pool Account to hold down the domestic price of hides, pelts and bobby calf skins was unfair and represented a transfer of money from the producing sector to consumers. Holland responded that farmers were doing very well economically, that the unions felt they should be sharing the benefits of high overseas prices and that the current industrial unrest was in part a manifestation of the envy that many felt about rural prosperity. By raiding the Meat Pool Account the Government in effect expected farmers to make a contribution towards overall economic stability.33 However, when overseas prices eased back in 1952, producers asked for help. As a means of keeping prices down they suggested reducing sales taxes. This was a request for subsidies by another name. Treasury, Industries and Commerce and Board of Trade officials all had different views on what to recommend to their ministers. In the end the status quo prevailed for a time.34

The cost of subsidies mounted. When those paid on some forms of transport were included, the total estimate for 1952-53 was £17.5 million. The list of subsidised goods included wool, butter, eggs, milk, calfskins, wheat and flour, gas, tallow for soap, and tallow for margarine. Bread, milk and butter subsidies were further raised in December 1953.35 Holland made it clear in his budget on 27 August 1953 that he was unhappy with the high level of subsidies. However, they were paid because, as a Treasury file noted, not to do so would ‘almost certainly’ justify an Arbitration Court wage rise, leading to further price rises.36 This was the same reasoning that had been used ten years earlier in the darkest days of the war.

Price controls were another source of tension within the Government. For many years they had been regarded as an essential concomitant to subsidies; if controls did not exist, then subsidies to producers were likely to escalate rapidly. But by 1950 price controls were also being applied to many unsubsidised items in the CPI. A total of 188 people, or 42 per cent of the entire staff of Industries and Commerce in 1951, was employed in the Price Control Division. Early in 1951, Professor Colin Simkin, a regular commentator on the state of the economy, detected a change in the atmosphere around Parliament; ministers were clearly showing signs of bowing to pressure to reintroduce price controls that they had earlier begun dismantling.37 Yet the National Government continued to talk of pruning unsubsidised items from the list of price controlled items. Clearly dissatisfied with the strong advocacy of controls from H. L.Wise, who was director of the division, Watts amended the Control of Prices Act during the 1953 session.38 In December he declared that the National Government believed that an ‘abundant supply of goods and free competition’ would ‘achieve better results and act as a more natural control of prices than any administrative system of price control’. He then added equivocally that price control was ‘an arm of economic policy’ which was necessary ‘only because of inflationary pressures, shortages, import restrictions, and other impediments preventing the operation of free competition’.39

Bernard Ashwin (left), Secretary to the Treasury 1939-55, with his successor, E. L. Greensmith, and Minister of Finance, Jack Watts, June 1955. ATL F-27633-1/2

With an election coming up and Labour’s stocks rising, Watts reconstituted the Price Tribunal under the chairmanship of Judge D. J. Dalglish. A study of profit margins and returns on capital was commissioned from a Wellington accountant, J. Haisman, while Dalglish conducted a lengthy inquiry into price control in March and April 1954. During the hearings there were disagreements between officials. The Associated Chambers of Commerce criticised Industries and Commerce views, suggesting they ran counter to the Government’s declared policy. Treasury produced a document in April 1954 entitled ‘Background to Price Control Policy’. It reviewed the effectiveness of price control over recent years and concluded that export and import prices, as well as supply and demand, played the major part in the domestic price structure and that price controls had had little impact. Treasury argued that it was ‘almost impracticable’ to control meat, fruit and vegetable prices, adding ‘if price control had not been in operation during the last few years it is questionable whether prices of the items now controlled would have risen much more than they did’. Arguments continued over the efficacy of price controls, but the inquiry of the Price Tribunal came down on the side of their retention in specified circumstances. Since inflation had begun to rise again, Cabinet accepted this advice. Ministers wanted the Government to be seen to be trying to bring prices under control in the run-up to an election. Show rather than substance was dictating policy. On 13 November 1954 the National Party held on to power, albeit with a reduced majority.40

In effect, National’s ministers were grappling with a tar baby; they did not like Labour’s economy but they could not figure out how to escape from it. Bureaucratic debate intensified. There was endless crossfire both within Cabinet and among officials. Those favouring continued controls kept the upper hand. Holland stated in January 1955 that the Government would ‘crack down’ on traders making ‘exorbitant profits’.41

The following month both the Manufacturers’ Federation and the Retailers’ Federation tried to argue that freedom from controls was not necessarily inconsistent with price stability. Watts, who became Minister of Finance after the 1954 election, bent in the direction of freedom; when opening the Retailers’ Federation conference in March 1955 he announced that the Government was prepared to release some goods from price control. A Control of Prices Amendment Bill in 1956 kindled hope amongst deregulators that the Government intended to shrug off price controls altogether, especially when Eric Halstead, who became Minister of Industries and Commerce in March 1956, talked of abolishing the Price Tribunal.42 Between 1955 and 1957 there was a slow but steady reduction in the number of bureaucrats within the prices section of Industries and Commerce. However, ministers remained edgy about the possible political repercussions of decontrol and the Tribunal survived. By now the wider community was having difficulty reading the National Government. In August 1955 Federated Farmers told Watts that their members were finding it ‘increasingly difficult to follow the Government’s policy on the questions of competition and price control’.43 This perception was damaging to the National Party, yet it lingered for many years. At no time before 1984 did the party manage to reconcile the conflicts between their philosophical goals and what was deemed necessary to retain office.

Establishing acceptable principles to govern imports was equally bewildering to Holland’s Government and bedevilled its relationships with the manufacturing sector. National’s first Minister of Customs, C. M. Bowden, who for the first year in office was also Minister of Industries and Commerce, issued a statement about the future of import licensing on 1 November 1950. He talked of the ‘urgent need to reform the import licensing system’ and declared that the National Government wanted to ‘abolish import control when possible’. He added, ‘To the extent that import control is retained, the purpose will be to conserve overseas funds and assist local manufacturers, at least until the adequacy or otherwise of present Tariff duties as a means of protecting local industries can be properly examined.’44 The new Board of Trade Act 1950 required the Board to advise the Minister of Customs about customs duties.45 Meantime in May 1950 an Import Advisory Committee had been set up under the Board. It was chaired by retired Supreme Court judge, Sir David Smith. It began a laborious examination of all tariffs. Ashwin supported the move away from import controls, favouring reliance on tariff protection. He told Smith that entry to New Zealand of as many as 300 items was currently prohibited for no other reason than to protect local producers from competition. This, Ashwin believed, was ‘a most unhealthy state of affairs’; such protection would eventually have to be done away with, and ‘the sooner the job is tackled the better’. He added that while ‘individual hardship’ might occur, an end to protection ‘would assist in reducing excessive demand and be in the general interest’. Referring to New Zealand’s obligations to GATT, which both Labour and National were slow to acknowledge, Ashwin told Smith that ‘we cannot afford to try isolationism in trade matters’ - a view that he also expressed regularly to ministers until his retirement from Treasury on 1 July 1955. 46

The work of the Import Advisory Committee moved slowly. Watts was anxious not to cause any disruption to local industries nor to threaten full employment. Some officials kept arguing that existing policies froze manufacturing on what, in some cases, was an ‘uneconomic basis’. One warned that ‘full employment to be secure cannot… be based merely on a policy of retaining existing labour and other resources in their present uses at all costs The objective should rather be full employment on a sound and lasting basis in which resources are given enough free play to find their most effective use.’47 This observation went to the crux of the Government’s difficulties; maintaining full employment by tight controls always seemed in practice to involve overshooting the mark. This resulted in huge numbers of job vacancies, despite an increase in the rate of immigration between 1951 and 1953. A high rate of job vacancies empowered unions who succeeded in winning settlements above award rates. A high level of domestic liquidity kept pushing up demand for imports. Meantime, tight controls reduced manufacturers’ flexibility. Some were permitted to move their factories into the suburbs or into small towns in search of workers. This had a beneficial by-product: more often than not it was women who answered the call and the percentage of women within the factory workforce rose from 23 per cent in 1948 to 25 per cent in 1962. But the incentives of the 1950s all conspired to keep investment locked into current production methods and product ranges. Governments viewed most changes as a threat. If manufacturers were allowed freedom to shift their resources about at will, then that would almost certainly result in pools of unemployment from time to time. Such a prospect terrified ministers.

The Government kept hoping it could gradually become more flexible. About 750 items had been removed from import control by 1951, although more than 300 items covering most of the main products manufactured in New Zealand continued to be produced in what the World Bank later called New Zealand’s ‘hothouse for local industries’. The pace of removal slowed; only twenty more items, most of them relatively minor, were delisted over the next three years.48 When the number of notified employment vacancies fell in 1953, ministers worried that the protective barriers around manufacturing might now be inadequate. Decontrolling the stabilised economy proved much harder than they first anticipated.

In his 1954 report Sir David Smith discussed the problems he had encountered with import controls, but concluded on an upbeat note:

Though some manufacturers did not object to the removal of import licensing, most of them have claimed that they could not survive without it. However, most industries which have been decontrolled are surviving very well. My own view is that the efficient New Zealand manufacturer who makes articles of good quality and who has been keeping his brand before the public, does not know how strong his position really is. He tends to overlook the fact that since the war wages actually paid overseas have increased and that freight and landing charges have all risen…. The local manufacturer also tends to overlook the fact that pride in New Zealand and in being a New Zealander has grown in recent years, and that with it, has grown … the desire to support New Zealand manufactures of good quality.49

Smith had put his finger on something important. Quick to grasp the State’s helping hand in the 1930s, many businessmen now needed much cajoling before they ventured forth on their own. As soon as Smith dropped back to a half-time role at the end of 1954, the Government’s enthusiasm for decontrolling imports and revising tariffs – which by now was little more than lukewarm – evaporated. In April 1955 the Auckland Manufacturers’ Association suggested abolishing the Board of Trade and its committees.50 Cabinet kept it, saying it wanted to decontrol more New Zealand-made goods ‘when general economic conditions are appropriate’,51 but the time never seemed to be right. In 1955 and 1956 when overseas prices sagged, some items were actually brought back under import controls again.

While the social engineers were arguing about how the Government’s social goals could be achieved within a more flexible environment, ministers were obliged from time to time to take short-term action to deal with reverses in the financial situation. When overseas prices were high in 1950-51, the Government failed to heed the advice from Smith and from Ashwin52 and was so generous with import licences that when the price of wool fell sharply over the summer of 1951-52, imports flowed into the country at an unsustainable rate. Ministers took fright and introduced a system of what was called ‘exchange allocation’. Officials were told not to use the word ‘control’, since it was contrary to the overall message which the National Party was trying to promote.53 Bank sales of exchange to importers were limited to 80 per cent of their purchases in 1950. Wherever an importer sought foreign exchange in excess of this basic allocation, a special application to the Reserve Bank was required. Such applications were decided on their merits after consultation with committees at Industries and Commerce. When import payments continued to exceed the Government’s target into 1953, exchange allocations were further reduced to 40 per cent of the 1950 figure. Exchange allocations were relaxed again in the run-up to the 1954 election.54 Many observed that National’s way of handling foreign exchange had become Labour’s by another name.55

In spite of large returns from primary produce in 1950-51, New Zealand’s overseas reserves ebbed and flowed for the rest of the decade.56 A constant shortage of overseas exchange was the single greatest threat to the full-employment economy. It became the centrepiece of a conference on economic stability held in Wellington in May 1953 under the auspices of the New Zealand Institute of Public Administration. Bureaucrats and academics who attended agreed that full employment, which in practice seemed to be ‘over-full employment’, inevitably resulted in demands for imports on a scale that outstripped New Zealand’s overseas earnings. This made import and price controls essential. There were a few dissenters. Leicester Webb, the former Director of Economic Stabilisation, implied in his speech that the era of rigid controls necessary to ensure that stabilisation worked was no longer feasible eight years after the war. He went further, asserting that the National Government’s creation of semi-autonomous marketing boards for primary produce, which had the capacity to fix farmers’ levels of remuneration in consultation with a Marketing Advisory Council of bureaucrats, had already made price stability unlikely.57 Others at the conference, most notably a Treasury official, G. J. Schmitt, son of the former Secretary of Industries and Commerce and a personal assistant to Ashwin, seemed more optimistic. Schmitt wrestled with various options available to the Government. He said:

I believe that it should be possible so to arrange the relationship between local prices and imports that demands for imports could generally be fully satisfied and yet that full employment could be maintained. Such a situation would be one in which local costs of production and prices were kept far below imported costs (by means of suitable exchange rate and tariff policies and by price control). Then any labour discharged from one employment would be immediately absorbed by another employer faced with a demand that he could not supply because of lack of labour, but which he certainly could win from his overseas competitor. The difficulty about such a system is that it would employ two price levels for similar goods or else an opportunity for businessmen to make considerable profits, which would be objectionable to some classes in the community. These profits would, however, be reduced by taxation. This alternative as a long term policy deserves closer attention….58

Schmitt’s speech was quoted widely and not always accurately.59 There was criticism. The New Zealand Herald headed an editorial ‘Economics of Socialism in the Treasury’.60 The Auckland Star was more judgmental about the goal of full employment, noting that the term had to it ‘a satisfying, complacent, fady prosperous sound to it’.61 The Hawkes Bay Herald Tribune adopted a more lofty overview to which hindsight gives some credence. The editor thought that New Zealand’s current prosperity had nothing to do with planning and was based instead on ‘bounteous and expanding production and high overseas prices’. If prices were to fall, then ‘the airy theories of the planners would provide no real solutions’. He concluded with the words: ‘In the long run our living standards depend on work and production. An economy based on planned scarcities is a mockery.’62

Schmitt’s speech caught the eye of the Herald’s Saturday satirist, Whim Wham. On 16 May 1953 he wrote:

Of Full Employment

And the full-fed Flaccidity that

That can provide,

You’ll just eat your Plateful

And try to look grateful,

For it’s Godzone Country

Where you reside.

The conference in May 1953 pointed up one of the fundamental problems of planners everywhere. Where their interventions did not at first succeed, most were prepared to try again. Wellington’s bureaucrats were searching to find the right balance between State and individual responsibility. In the spirit of paternalism that had become a central feature of New Zealand welfarism, they believed that they, rather than the market, could find the answer to problems. Besides, regulations and controls produced an ever-growing public service from which officials could not fail to benefit. M. J. Moriarty, a later Secretary of Industries and Commerce, pointedly asked the conference to consider ‘whether we are retaining a sufficient central direction of economic affairs to create the conditions in which stability may be obtained’.63 For most who were present, the question was rhetorical.

There was no obvious diminution of the role of planners within Industries and Commerce during the 1950s. Clinkard retired in 1950 and P. B. Marshall returned to head the department until he, in turn, retired in 1957. Some departmental committees were abolished and many aspects of the Government’s assistance to manufacturing were reassessed during 1952-53. The number of permanent officials in the department subsided, standing at 316 on 31 March 1956.64 Yet, having dislodged Dr W. B. Sutch from his position at the United Nations because they did not trust his politics, National ministers seemed powerless to prevent the arch proponent of protection and planning from returning to a senior research position within Industries and Commerce. In 1956 he was promoted to head the division dealing with manufacturing protection and development, as well as import controls.65

By the middle of the decade departmental officials were keeping tabs on most aspects of the economy and were strongly encouraging any industry deemed to have export potential. Officials were building up files on every imaginable economic activity in New Zealand. Among the department’s thousands of files are ones on buttons, clothing, stout, wine, deer, tobacco, seaweed, split peas, fruit cases, stationery, toys, stock feed, dog food, pig bristles, cattle horns, creosote, soap, sports goods, wallboard, bicycles, nuts and bolts, plastics, space heaters, wire, anchors, tyres, nylons and full length hosiery. Boarding houses, funeral charges and tailors’ prices came under bureaucratic scrutiny. Permission was needed for constructing a flour mill in Oamaru, expanding a plant making insulating material in Otahuhu, or the purchase of new cranes for the Tauranga waterfront. The Land Settlement Promotion Act 1952 set out to prevent undue aggregation of land. A Land Valuation Committee was charged with deciding whether a farm already owned was sufficient to support the would-be purchaser of land in a ‘reasonable manner and in a reasonable standard of comfort’. Additional purchases were authorised where they were likely to raise a farmer’s standard of living ‘to a level more in keeping with that of the majority of the farming community or where the public interest favours the expansion of his farm’.66 Nothing, it seemed, escaped the eye of officialdom.

Dr W. B. Sutch, the controversial Secretary of Industries and Commerce (1958-65), who never doubted the desirability of state activity. ATL C-23147

For many years the National Government was unable to decide whether to retain Labour’s Industrial Efficiency Act 1936, the Bureau of Industry with its licensing regime, as well as the restructured Board of Trade. The concept of licensing appealed to some businessmen but offended others. Watts, who was liked by officials (one recalls him as ‘efficient, well balanced and capable of quick decisions’),67 could vacillate on some issues like his colleagues. He was never happy with industry licensing, yet a deteriorating balance of payments situation by 1956 seemed no time to surrender any control mechanisms. A new Industries and Commerce Act came into force on 1 April 1957. A pale imitation of the draft bill that had circulated a decade earlier, it nonetheless provided the department with very wide powers to promote and encourage industry and exports, and to assist with the location of industries ‘in those localities most economically suitable’. The Act repealed the Industrial Efficiency Act 1936, but the powers of the Board of Trade 1919 were retained and continued licensing of industry was provided for in the Licensed Industries Regulations 1957. The number of industries requiring a licence was now less, but the manufacture of pulp, paper and board, paua shells for sale, and tyres and tubes remained on the list.68

While there were frequent bursts of rhetoric about the virtues of self-help, using the State’s powers to assist farmers was something that came naturally to the National Government. In his budget of 1950 Holland extended grants to wheat growers. Robbed of market prices under rigid stabilisation, they found Labour’s subsidies did not produce a return that was as good as could be obtained from alternative uses of the land. In the late 1940s wheat had to be imported once more. Tax exemptions for farmers had initially been introduced by Nash. Holland extended them to include drains, fences, dams, erosion, landing strips and clearing weeds. Generous depreciation allowances were allowed on farm equipment, accommodation and farm buildings. The importation of agricultural machinery in the early 1950s reached all-time records. By 1955 few farms were without tractors and many possessed other expensive and often rarely used implements as well.69 New subsidies were introduced to keep down the cost of imported phosphates, while farmers were able to claim back the sales tax on petrol used in farm machinery.70 Assistance in the form of tax breaks for primary industries became a regular feature of budgets from the 1950s until the early 1980s.

Unknown to most people was the level of state assistance enjoyed by primary produce marketing boards in the 1950s. For many years governments tolerated a system where boards were allowed to finance their seasonal overdrafts with Reserve Bank credit at 1 per cent interest. The Meat, Apple and Pear, Citrus, Honey, Milk and Poultry boards were all treated in the same way but the Dairy Board usually ran the largest overdraft which frequently peaked at £30 million. When surpluses built up in the Dairy Board’s accounts it was allowed to invest in government stock at between 3 per cent and 3.75 per cent. Treasury officers constantly opposed the continuation of what amounted to backdoor subsidies to boards and Watts admitted in 1955 that ‘they have no real entitlement to the preferential treatment they now receive’.71 However, the time was never opportune to end the privilege. When export prices turned down in 1957 and the Dairy Board sought to increase its overdraft at 1 per cent interest in order to tide farmers over low prices, the Labour Government tried to force the board to accept market rates of interest. When this was stoutly resisted, the Government decided to be more open about its assistance. A direct subsidy of £5 million was included in the 1958 budget. There then followed many months of behind-scenes warfare as the Dairy Board not only sought to have the loan treated as a gift but requested further 1 per cent finance to use on plant, vehicles, advertising and administrative costs. Ultimately Holyoake’s National Government wrote off the £5 million. Boards returned to their 1 per cent interest rates, with National MPs always defending them from any criticism. In 1973 Brian Talboys, a former Minister of Agriculture, claimed ‘there is no more imaginative, businesslike, and energetic marketing organisation in this country than the New Zealand Dairy Board’. He failed to acknowledge that much of it was being done with ‘cheap’ money.72

Whenever one sector’s efforts were seen to be rewarded, others argued for similar largesse. National, like Labour before it, developed its hierarchy of the deserving and assiduously looked after its supporters. But as the raft of tax breaks and subsidies to the agricultural and business sectors expanded, the Government’s revenue base slowly contracted. It became noticeable that ordinary wage and salary earners, in whose interests the welfare state had been devised, enjoyed few opportunities to write off expenses. They shouldered a growing portion of the country’s taxation. This became one of the biggest inequities of the centrally directed welfare era.

In a burst of entrepreneurial zeal worthy of Vogel or a later prime minister, Robert Muldoon, Holland’s Government became directly involved in the construction of the biggest industrial project in New Zealand’s history until that time. The story of the origin of the Tasman Pulp and Paper Company has been told in part by Morris Guest.73 By the time of the change of government in 1949, the only thing holding back development of a major pulp and paper plant to process the State’s quarter million acres of exotic forests in the central North Island was a shortage of development capital. Pat Entrican of State Forests had long been urging a state-funded project, arguing at one point that having the Government involved in forestry was ‘as essential… as the maintenance of law and order’.74 In the meantime he succeeded in blocking the granting of a licence to Forest Products and Whakatane Paper Mills for production of newsprint.75 Entrican convinced his minister, C. F. Skinner, of the need for state involvement in the production of pulp and paper. In April 1949 the Labour Cabinet approved ‘in principle’ the construction of a mill. Ministers believed that there was a net gain to be made in foreign exchange and that the State ‘could do certain jobs just as well as private enterprise’.76 Meanwhile, Fletcher Construction’s interest in building such a mill was growing.

A. R. Entrican, Director of the New Zealand Forest Service, who had visions of a huge state forestry enterprise, with him running it. National Archives

Ashwin, however, kept warning Nash that a development estimated to cost at least £10 million would overstrain the Government’s resources at a time when there was already huge state investment taking place in hydro-electricity construction. Citing the example of British Petroleum, which had carried most of the costs of its entry into the New Zealand marketplace in 1946-47, Ashwin argued that overseas interests should be encouraged to put up the capital to develop the increasingly valuable forest asset.77

The National Party at first seemed to oppose what was known as the ‘Murupara project’. Keith Holyoake described it as a ‘senseless scheme’, although he later claimed to be have been opposed to it only if the Government had to finance the mill. In August 1950 Holland and his Minister of Forests, E. B. Corbett,78 took Ashwin’s advice and decided to test world interest in developing a mill to process trees from the Kaingaroa Forest. The Prime Minister made it clear he preferred not to invest state capital in the scheme. Enticing overseas investment, however, proved much harder than either politicians or their officials anticipated. On 1 April 1951 Corbett issued proposals for the right to purchase for a period of 75 years an annual quantity of 23 million cubic feet of exotic softwoods and to cooperate with the New Zealand Forest Service in developing an integrated plant consisting of a sawmill, a pulp mill and a newsprint mill. The Government reserved the right to subscribe 15 per cent of the share capital. It declared a willingness to provide power for the plant, said it would construct a ‘modern overseas port’ at Tauranga, provide a railway connection to the port, build 400 rental houses at the plant for employees, and assist with immigration for ‘any skilled workmen’ the purchaser might wish to bring to New Zealand. The document invited proposals by 1 November 1951 for constructing an ‘integrated plant’.79 Big government was getting even bigger.

State money created a town at Kawerau, helped build Tasman Pulp and Paper (foreground), a railway line to the port at Tauranga and new berthing facilities. National Archives

In spite of efforts by Fletchers to round up British and American investors, none was forthcoming. Those Americans who had been identified as possible investors in the mill were involved heavily at the time in their own North American ventures. When tenders closed, a hastily cobbled-together scheme from a newly formed, and as yet unregistered company, Tasman Pulp and Paper, was the only bid received. Fletcher Holdings Ltd was prepared to put £700,000 (44 per cent of the value of Fletcher Holdings at the time) towards the anticipated cost of building the mill. The rest of Tasman Pulp and Paper’s money would come from borrowings, debentures and the Government’s 15 per cent contribution.80 An officials’ committee was set up to examine the proposal, and to review market possibilities for newsprint. Eventually it was concluded that 46,000 tons of an anticipated annual production of 75,000 tons of newsprint could probably be exported to Australia.

By now Ashwin was worried that the Government seemed to be the underwriter of the mill’s construction and would be carrying all the costs of the infrastructure as well. The infrastructure was estimated to cost approximately £15 million. On 7 December 1951 the committee recommended that the scheme go ahead only if an overseas loan for a substantial part of the total cost of the mill and its infrastructure could be raised – which it eventually was. After a long wait, a loan of £10 million at 4.75 per cent, raised by the New Zealand Government from the American Export-Import Bank, was confirmed in November 1953. Meantime, in the expectation of finding the money, the budget of 1952 had announced that some of that year’s surplus due to the previous year’s wool boom would also be put into the total Tasman development. Treasury arranged overdraft facilities for the mill’s construction. Plans for a public float were put into operation in 1954. While Sir James Fletcher chaired the new Tasman Pulp and Paper Co. Ltd that was registered on 2 July 1952 and his son, J. C. Fletcher, and an Auckland solicitor, L. J. Stevens, represented the private sector, three top public servants, Ashwin, Entrican and E. R. McKillop, Commissioner of Works, were also on the initial board. Its first secretary, who was appointed in August 1953, was G. J. Schmitt, whose father had played such an important role in encouraging manufacturing under the Labour Government.81

As a series of intense discussions and knife-edge negotiations proceeded, the National Government warmed to the vast project. On 21 July 1954 Holland adjourned the House in order to discuss the Government’s involvement. In some pre-election hyperbole he claimed that as a result of the Tasman scheme the country was ‘just leaping ahead’. More than £2 million of state money had already been spent and he anticipated that another £13 million would be needed for the railway line, 450 houses at Kawerau where the plant was being built and another 300 at Murupara in the centre of the forest. Labour supported the project, seeing it as a forerunner of further joint enterprises, a sentiment that was endorsed by the National MP for New Plymouth, who hoped that the Government would assist with the development of oil, iron and steel projects in Taranaki.82 By the time the newsprint machine started up on 29 October 1955 the State had contributed £2 million of the £6 million share capital in Tasman and it owned half of Kaingaroa Logging Co. Ltd, which acted as a link between the Forest Service and the mill by supplying it with logs. The Government had also, as promised, financed all of Tasman’s infrastructure.83

Tasman expanded its share capital on 1 January 1960 by bringing in the English newsprint producers, Bowaters, who had mills in Canada and the United States. Bowaters’ willingness to transfer some large newsprint contracts to Tasman was instrumental in further expansion at Murupara. Government overdraft guarantees were forthcoming in 1960 and a second newsprint machine opened in December 1962. By this time, after some years of well-intentioned if inexperienced management, Tasman had moved into black figures. However, according to Geoff Schmitt, who became Managing Director in 1963, the Government’s taxation regime, and particularly its depreciation allowances, delayed, rather than assisted, the company’s struggle to profitability.

At the point where the State sold its shares in 1979, taxpayers had not yet reaped the dividends they deserved. However, a major addition to New Zealand’s industrial infrastructure had been made. Kaingaroa forest was now being managed in a sustainable manner and, true to the spirit of import substitution, New Zealand publishers were receiving paper from local mills. The balance of payments was benefiting from exports of the mill’s surplus. Moreover, the port facilities at Mt Maunganui were soon also being used for pastoral and horticultural exports. There can be no doubt that much of the stimulus to growth in the Bay of Plenty region resulted initially from the forestry industry. And the precedent of joint state-private sector involvement in major industrial projects had been established, something which Walter Nash’s Government built on with plans to develop a steel mill and Robert Muldoon carried to excess with his ‘Think Big’ projects of the early 1980s.

Tasman eventually played a significant part in reducing the deficit in New Zealand’s trans-Tasman trade. It was a largely unprotected, international company that was expected to operate competitively on the world market. This was not easy. Tasman’s first few years were difficult and losses piled up. It was the backing of the Government, its continued confidence in Sir James Fletcher, his son (J.C., as he was known) and Geoff Schmitt that helped the company to survive its early years. When the company got into serious strife in 1977 and faced bankruptcy, it was the Government that backed it. By this time there were new people in charge; the Government insisted on some further changes at the management level as the quid pro quo to further support.84

Comfortable personal relationships developed between private sector leaders, bureaucrats and politicians. Lunches, drinks or ‘cold calls’, as J. C. Fletcher called them, where businessmen visiting Wellington would call unannounced on senior Industries and Commerce officials, bankers and politicians, were common. Occasional access to company holiday homes or boats for officials, union leaders and politicians kept the world of the controlled economy ticking along.85 In an era of generous tax allowances and cost-plus pricing, the costs were easily passed on to consumers. Surprisingly, perhaps, it was not a world where corruption thrived, although in other countries regulations and controls were often exploited by officials. In the life of New Zealand’s centralised economy there were very few prosecutions and only occasional rumours of kickbacks, many of which turned out to be without foundation when subjected to scrutiny.86

While Tasman Pulp and Paper involved the biggest outlay of government funds on any single enterprise to date, it was by no means the State’s only new business venture in the first postwar decade. The New Zealand and Australian governments were the sole (and equal) partners in Tasman Empire Airways Ltd, which flew to Sydney, Nandi, Aitutaki and Papeete. TEAL had a capital of £2 million. By 1956 it had also received an advance from the New Zealand State Advances Corporation of a further £550,000. Cabinet appointed the company’s directors. The Sydney and Nandi routes, which connected with international flights further afield, posted profits but the ‘Coral Route’ to the Pacific islands continually ran at a loss.87

National Airways Corporation was founded in 1946 when the Government took over several small aviation companies after having controlled most of their planes under emergency regulations for much of the war. The corporation’s capital of £1 million was entirely provided by the New Zealand Government which, as with TEAL, was directly involved in the purchase of new aircraft and the building and modification of airports and hangars. Holland’s 1950 proposal to sell NAC came to nothing. The airline was advertised both in Australia and the United Kingdom but in the end no applications considered acceptable to the Government were received. A file note in 1957 observes that private capital had been scared away because so many factors influencing the profitability of NAC were under the control of the Government, especially charges for airways facilities which were owned, operated and maintained by the Crown. Government also set airport dues for the use of runways and facilities. A statement by the Labour Party that if NAC were to be privatised, a Labour Government would repurchase it at the first opportunity, also acted as a disincentive to any would-be purchaser.

A National Airways Corporation’s workhorse, the DC3, at Paraparaumu, 1951. ATL F-40512-1/2

In 1953 the National Government decided instead to restructure the corporation’s board of directors and to retain the airline in public hands. While NAC’s passengers, freight and profits continually grew during the 1950s, considerable advances of government money were needed to finance the purchase of Vickers Viscount and Fokker Friendship aircraft between 1957 and 1961. Moreover, smaller centres that were anxious for air services usually took their case first to the Government rather than NAC. The corporation was never free from political interference.88

Before his death in 1947, D. G. Sullivan involved the Government in a joint venture with Skellerup Industries Ltd and Cerebos Salt to develop the natural salt deposits at Lake Grassmere. It was called the Dominion Salt Co. Ltd. The State’s input to the faltering company increased in 1949 and by 1956 £150,000 in 4 per cent preference shares had been taken up by the State. This amounted to 25 per cent of the company’s total capital. A report to ministers in 1965 suggested that the company was trading on its monopoly status, and that its management ‘leaves much to be desired’. The Government was discovering that monopolies had to be carefully monitored. Yet, when the company was restructured in 1965 the Government invested another £150,000 in it. Once involved with ventures, the State found it extraordinarily difficult to resile from them.89

In 1953 the Government also set up the New Zealand Packing Corporation to begin vegetable and fruit processing factories and related trading in quick frozen and dehydrated products in Pukekohe and Motueka. The corporation spent £294,000 on the two plants which posted a net profit of £42,000 in the year to 31 October 1956. The whole venture was conceived as a seeding operation; it remained in the Government’s hands for barely five years, at which point it was sold.90

While it tolerated public control in some areas and experimented itself, the National Government tried to reduce the cost of the bureaucracy. In January 1952 a Committee on the Machinery of Government was established with the Acting Prime Minister, Keith Holyoake, in the chair. Holyoake informed the Treasury and PSC representatives who were present that he wanted to ensure ‘proper organisation of the machinery of government’. Over the next two years ministers rearranged several government departments. By restructuring the Public Service Commission in 1951 and removing the PSA’s nominee, ministers were trying to halt the inexorable rise in the number of public servants that had been such a feature of Labour’s administration. In April 1952, with numbers totalling 53,437 (52,046 on 1 April 1950), the Machinery of Government Committee turned its attention to retirement rules for state employees with a view to ceasing the practice whereby many stayed on after age 60.91 The rate of growth in the number of state employees slowed. The committee also recommended abolishing the Town Planning Board. In 1953 the Town and Country Planning Act amended the original legislation of 1926 by devolving more power to local authorities whose decisions could be appealed to a Town and Country Planning Appeal Board. However, National’s desire for efficiency in central government did not stretch to concern about wastage at the local level. Holland’s Government pulled back from Labour’s plans to reform local government. The political preserve of many National Party functionaries, local councils escaped restructuring until a Labour Government undertook the task between 1985 and 1989.92

National’s record with railways provides further evidence of expediency. Conscious that the number of railway employees had grown steadily under Labour, a Royal Commission recommended in 1952 that a Railways Commission be established to administer the service. The goal was to remove railways from political control once more and to oblige management to run ‘efficient and economical passenger and goods services’.93 After passage of the Government Railways Amendment Act 1952 five directors were duly appointed on 12 January 1953. By restructuring services and applying a policy of user-pays, the Commission quickly turned Railways from a loss of £1.4 million in 1952 to a profit of £1.46 million in 1955. In the process, however, the sensitivities of many locals were trampled. Major protests developed in Nelson when the long-promised, but only partly constructed line to Inangahua was scrapped and the rails lifted. Further trouble erupted in 1956 in the Hutt Valley, where the electric train service was losing more than £230,000 pa and the feeder bus service another £75,000 pa. The Commission sought to remedy costly duplication in Railway Road Service and train timetables and questioned whether the bus service might be sold. While in theory the work of the Commission was at arm’s length from the Government, Labour MPs blamed the Minister of Railways for every tough decision made by the Commission. With a difficult election coming up, ministers were sensitive; National held the Nelson seat by a narrow margin and both the seats of Onslow and Wellington Central were barely Labour’s way. The following parliamentary exchange in October 1956 provides some of the flavour of the debate:

Mr Michael Moohan (Lab. Petone): ‘The buses are public property, and are owned by the Railways Department. It is the job of the Railways Department to provide an internal service throughout the Hutt Valley, in addition to the electric train service. Everyone does not live on a railway line. We want a positive, progressive policy.’

Mr J. J. Maher (Govt. Otaki): ‘Even if the service shows a substantial loss to the taxpayers generally?’

Mr Moohan: ‘The Government is showing bigger, better and brighter losses for every activity it handles…. The people in the Hutt Valley are entitled to the best passenger service possible.’

A few minutes later Philip Holloway, the new MP for Heretaunga, reminded the minister that regulations prohibited private sector competition with railways, so the Government had no option but to provide a bus service. ‘Unless a change is made by legislation, the Government has undertaken for all time the responsibility of giving a good and efficient bus and rail service.’94

To Labour’s astonishment, the Government crumpled. During the committee stages of a minor Railways Amendment Bill a few days later, the minister tabled a Supplementary Order Paper abolishing the Commission and returning Railways to ministerial control, where both Labour and the public clearly felt effective power should reside. National’s brief experiment with efficiency in railways had come to an abrupt halt. Railways posted a small loss in 1957 and the following year was in red figures to the tune of more than £1 million.95 But there was no gratitude from the voters; National lost Nelson in the 1957 election and Labour’s majorities in both Onslow and Wellington Central increased.

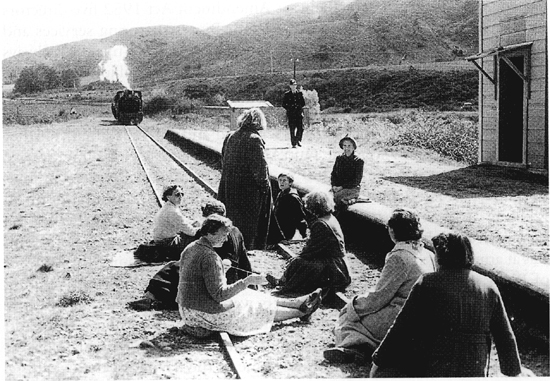

Sonja Davies (on the rail track facing the camera) leads a group in protest at plans to close the uneconomic Glenhope railway line, 1954. Nelson Provincial Museum

As big government grew more expensive, so did the cost of maintaining Labour’s social programmes. In the years after the war, expenditure on Social Security, Health and Education consistently grew at a faster rate than the economy as a whole.96 Most social security benefits were boosted in 1950-51, and allowable extra incomes were raised. The level of payment of Universal Superannuation to 65-year-olds doubled in October 1951 and the rules covering Widows’ Benefits were made more generous in 1954.97 Health costs marched steadily ahead. Decision-making had been largely centralised by 1950. Departmental files show that most items of expenditure went to Wellington for authorisation; the purchase of flannelette for hospital boards went to Treasury for authorisation in October 1951, Cabinet approval was needed before £6,677 was spent on sealing the road to Tokanui Hospital the following year. When Hastings needed £3,136 to fund a pilot project to fluoridate the water supply in 1952, Cabinet had to approve. Even an ex gratia payment of £14 to a St Helen’s Hospital patient whose coat had been accidentally damaged had first to be cleared with the Director General of Health.98

Ministers Watts (left), Holland (centre) and Doidge (right) lobbied by hospital nurses at Parliament Buildings, May 1951. ATL F-27630-1/2

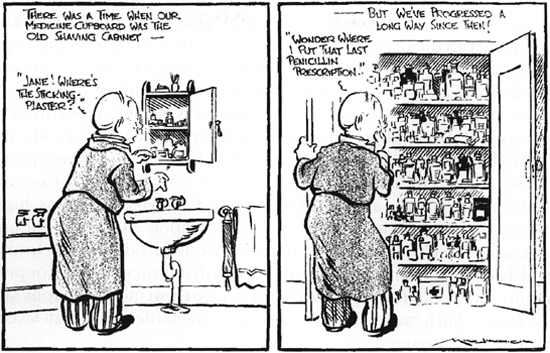

Despite tight control over incidental expenditure, the cost of public hospitals kept exceeding budget and officials proved unable to stop it. Some local authorities complained about being expected to contribute towards hospitals when there seemed to be so little control over their escalating expenditure. In 1950 the Director of the Hospital Division within the Department of Health admitted he was concerned at rapidly mounting costs. Available beds had grown by 33 per cent during the previous decade, the number of outpatients by 212 per cent, and staff at public hospitals now numbered 15,468 or 86 per cent more than in 1940. Big salary adjustments had recently been made to assist boards to find enough qualified staff.99 In February 1952 the department warned the Secretary of the Treasury that hospital boards were likely to spend £862,000 more than the £7.2 million allocated to them in the budget – a cost overrun of more than 12 per cent. Ashwin, in turn, told Holland that in his opinion, the Department of Health ‘should take active steps to induce boards to exercise economy in expenditure and also for the Department to achieve savings in other items of its vote’. Of the 37 hospital boards then in existence, 24 had overspent during the year. Proper expenditure control should, in Ashwin’s view, ‘be a condition of next year’s grant’.100 This refrain was sung every year in the decades that followed.

Marshall was Minister of Health by this time. He told the Prime Minister that the overruns ‘demonstrate the lack of effective control on the expenditure of Hospital Boards and the tendency for independent boards who are responsible for expenditure, but not for raising the money, to be less careful than they might be in controlling expenditure’.101 Marshall had identified the principal problem with boards. Having found it, however, he compounded the problem by relieving boards of their remaining obligations to raise revenue through local property rates, which in 1950 contributed 21.7 per cent of public hospital expenditure. From 1952 there was a progressive reduction in the local rate levy to support public hospitals and, in the Hospitals Act 1957, central government took over sole responsibility for funding all public hospital services.102 Locally elected boards, however, continued to exercise power over hospitals and their services. A departmental analysis of health services prepared in 1974 noted that once boards no longer had to provide part of the finance themselves, ‘their expenditure escalated’.103

The school dental service, 1954. ATL F-30256-1/2

Holland’s Government sought to restructure the hospital system in order to bring ballooning expenditure under control. A Consultative Committee on Hospital Reform was established under the chairmanship of Harold Barrowclough, who was shortly to become Chief Justice. The committee’s report of February 1954 suggested amalgamating many of the smaller boards, decentralising the Department of Health into five regional authorities, and assisting private hospitals to take some of the surgical load off public hospitals. The same considerations that led National to tread softly with local government reform now caused them to shy away from forced hospital board amalgamations, although several boards voluntarily joined with their neighbours over the next decade.104 Nor did a government which was centralist in practice, if not at heart, agree with regionalisation. Loan facilities, including suspensory loans, were extended to private hospitals after 1952 and in 1957 a wage and salary subsidy for private hospitals was also made available. Meanwhile, the patient/day subsidy for private hospitals that had been paid by the Government since 1939 was increased from time to time. In 1969 a consultation subsidy for visits to specialists was also introduced.105

A dual system of health care developed steadily from the 1950s and in 1961 several Auckland surgeons formed the Southern Cross Medical Care Society which provided an insurance scheme to cover private health care. Some years later the Government was persuaded to make contributions to private health insurance tax deductible to encourage self-help. By 1984 more than 35 per cent of New Zealanders were enrolled in the supplementary private health care system.106 There is no indication that subsidising the private sector restrained the rate of increase in public hospital costs, although a leaner private sector that could be selective in the medical interventions it chose to perform was often held out to be more efficient than the swelling public sector.

The short-lived Labour Government between 1957 and 1960 endeavoured to bring public hospital building programmes under control, perceiving that the on-going running costs soon exceeded the initial price of any building or new piece of equipment. However, the introduction of equal pay for state employees in three stages in 1961-64 had a big impact in the hospital sector with its predominantly female workforce.107 In June 1966 the Minister of Health, Donald McKay, advised boards that they must keep within their budget allocation of £88.7 million for that year. They took little notice. Boards overspent by £2 million and the Health Department now began a much more systematic scrutiny of their budgets. This too had little effect.

By the late 1960s rising inflation and costly relativity disputes between groups of health workers, all of them ultimately solved at the Cabinet table on an ad hoc basis, pushed costs along. Political expediency can again be observed behind both the pay agreements and a willingness to approve large numbers of additional staff in election years.108 In 1971 mental health workers bypassed their salary-fixing procedures, went straight to the Prime Minister and got what they wanted. The same happened with dental nurses in March 1974 when they invaded Parliament Buildings en masse. On that occasion Labour’s Prime Minister, Norman Kirk, ordered his minister, R. J. Tizard, to ‘get those nurses out of this building’. They departed with a better pay settlement than they had been able to negotiate so far.109 Remuneration within the public sector was meant to be settled by established mechanisms. Health and education workers were learning that carefully placed media publicity, and threats of direct action, usually resulted in ministerial intervention. The results of such unbudgeted wage settlements were simply sent on to the taxpayer.