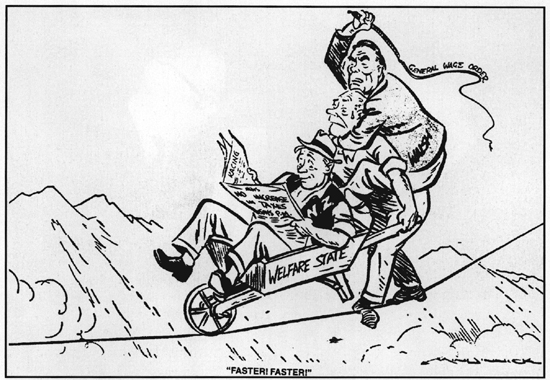

Once the National Party had tempered its free market rhetoric in the early 1950s and adjusted to the regulated economy, arguing in effect that its ministers were better able than Labour to administer the welfare state, the scope of political debate in New Zealand narrowed. Labour candidates occasionally spoke of ‘socialism’, although it was now an ill-defined creed, meaning little more than a general willingness to keep on using the State’s powers. Between 1957 and 1984 both main parties accepted price controls, subsidies, tariffs, import and credit controls; only a few differences in emphasis lay between the two. Labour enjoyed only six years out of the 27 in office; its ministers were cautious fiscally, but more likely than their opponents to increase funding for social services. National, on the other hand, always preached freedom, extolling the virtues of a world with fewer controls, but moved cautiously. The ratchet upwards of state involvement in the economy was difficult to reverse. As a result many voters perceived that elections had become a choice between Tweedledum and Tweedledee, where the rhetoric was out of all proportion to the likely consequences of one or other of them being elected.1

Not surprisingly, a gap opened up for a third political party. Building on a hankering after monetary reform that dated back to dairy farmer angst in 1934-35, and the ‘wild money men’ who wanted free use of Reserve Bank credit2 during the early days of the First Labour Government, the Social Credit Political League fielded a full list of candidates for the 1954 election. It won 8.62 per cent of the total vote on that occasion, but no seats. One commentator likened the new party to the French Poujadist movement of the 1950s - ‘the one-man businessman’s detestation of the taxes which fuel the contemporary state, his resentment of the controlling paperwork which overwhelms him and his suspicion of the unionists whose highest ranks rival him in status while their lower ranks assert standards for paid help which he cannot meet’.3 Holland’s Government established a Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Monetary, Banking and Credit Systems in March 1955. It placed Social Credit’s nostrums on trial, took copious evidence, and politely conveyed the verdict that they were muddle-headed.4 Since the major parties had become – to use Harold Innes’s phrase - ‘as attractive politically as yesterday’s cold rice pudding’, Social Credit retained a capacity to act as a spoiler between the two main parties for the next 30 years. Its popularity waxed and waned according to the degree of irritation voters felt with National and Labour. Social Credit won an occasional seat, redefined its messages but succumbed eventually to the collapse of the corporate state in the 1980s and the emergence once more of significant philosophical differences between the two main parties in the 1990s.5

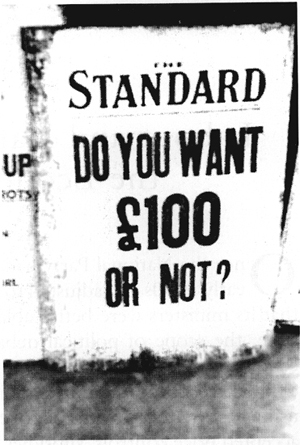

Elections had become auctions by the 1950s. Labour’s newspaper billboard puts the question bluntly in November 1957.

Both Labour and National felt it politic to resort to extravagant promises at election time in the hope of gaining support – and then to accuse each other of using ‘bribes’. Labour’s carelessly expressed promise to reduce income tax to coincide with the introduction of PAYE in April 1958 led their weekly, the Standard, to publish a billboard on the eve of the 1957 election reading ‘Do You Want £100 or Not?’6 There were many more electoral ‘bribes’ over the years ahead, culminating in what historian Keith Sinclair regarded as the biggest of them all,7 when Robert Muldoon promised in 1975 – and delivered fifteen months later – National Superannuation at the rate of 80 per cent of the average ordinary time wage to a married couple over 60, without raising taxes.

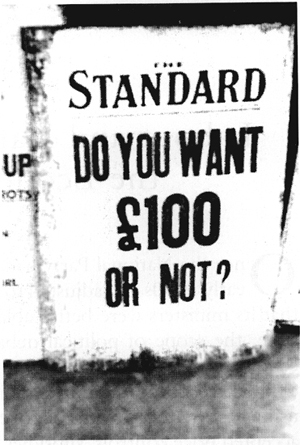

When they took office on 12 December 1957 Walter Nash and his Minister of Finance, Arnold Nordmeyer, found themselves facing a substantial foreign exchange crisis. For the year to March 1958 imports exceeded exports by nearly £40 million. By 1 January 1958 the net overseas assets of New Zealand’s banking system had fallen to less than £45 million, the lowest level since the war. Butter, lamb and wool prices continued to fall for most of 1958.8 Between the last quarter of 1958 and the last quarter of 1959 world trading conditions improved and export prices rose, but they sagged again in 1960. The New Zealand economy was entering a much less stable trading environment, one that placed Savage’s insulated economy under greater strain.

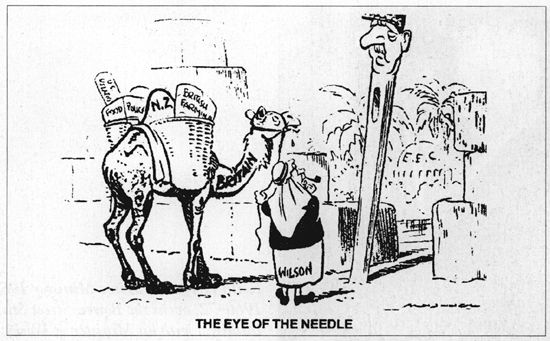

By this time New Zealand was beginning a long fight to retain access to the British market. Slowly after the war Britain became immersed in the negotiations taking place within Europe over the formation of a common market. Discussions culminated in six continental countries signing the Treaty of Rome in March 1957. In spite of soothing visits from British ministers, including Prime Minister Harold Macmillan in January 1958, New Zealand’s fears mounted. By 1960 the six were formulating a common agricultural policy and the following year Britain announced that it would apply to join what was becoming known as the European Economic Community (EEC). Some of the strongly protectionist attitudes of EEC members clearly threatened New Zealand’s trade. Eventually Britain joined the common market on 1 January 1973 and the issue of continuing membership was put beyond doubt in a referendum in 1975. Despite prolonged efforts and a few successes in the fight to preserve access to Europe for its former colonies, such as the Ten Point Plan for New Zealand announced in Luxembourg in June 1971, Britain accepted the rules of the common market, thus turning its face against its imperial past. The impact on trading relations with Commonwealth countries was immense. New Zealand could no longer regard itself as Britain’s outlying farm. The search for new markets for old products stepped up.9

Faced with the exchange crisis of 1957, Nash and Nordmeyer acted as though it was a repeat of the predicament faced by the First Labour Government in 1938. This time, however, Labour ministers were able to blame their opponents. In a radio broadcast on New Year’s Day the Prime Minister claimed that the National Government had allowed ‘the most rapid slide in the history of New Zealand trade’ to occur.10 He ruled out devaluation, overseas borrowing and a sudden reduction in purchasing power. Reflecting the current attitude that general prosperity rested on the welfare of farmers, Nash announced that priority would be given to dairy farmers, who would be paid their guaranteed price even though it was higher than current export receipts. Of particular significance was Nash’s announcement that the Government would return to comprehensive import licensing to safeguard overseas reserves. A new schedule for import licences was issued; all previous licences were revoked. Credit would be carefully controlled to restrain demand. Over the next two years it also became necessary, despite Nash’s better judgement, to borrow in Australia, New York and London.

Walter Nash, Prime Minister 1957-60, back at his desk at 10.40 pm after a dinner party, December 1959. Auckland Star

All this sounded ominously like a return to wartime austerity. Keith Sinclair caught some of the flavour of the moment when he described Nash as sounding like Father Christmas one minute and Scrooge the next. The National Party dismissed Nash’s ‘crisis’, claiming that reserves were greater than the Prime Minister admitted and that Labour’s real intention was ‘to slip a straitjacket’ of controls and regulations on the economy once more.11 While it seems clear in retrospect – although it was much debated at the time – that the National Government had let the economy run in 1957, it was also true that Labour ministers felt more at home in a controlled environment; more than two thirds of Nash’s Cabinet had been in Parliament during the Savage-Fraser era, several of them in senior positions. As if to underline their faith in controls, early in 1958 Cabinet approved the appointment of 50-year-old Dr Sutch to fill the position of Secretary of Industries and Commerce, which had been vacant for many months following the retirement of P. B. Marshall.12 Ever since his days in Coates’s office, Sutch had been an evangelist for big government and the notion that it would always produce better social results than the marketplace. He was an economic nationalist who believed passionately in the effectiveness of import controls. The minister with whom he worked after 1960 was to praise Sutch’s intelligence, his imagination and enthusiasm but called him ‘a strange, frustrated, arrogant, secretive man with a brilliant quicksilver mind, facile, ingenious, crafty, devious, deceitful’.13

With the encouragement of the young, energetic Philip Holloway, who was his minister between 1957 and 1960, Sutch began boosting departmental numbers once more, actively recruiting university graduates to his cause.14 The tone of departmental reports became urgent. Sutch painted a grim future for New Zealand unless there were comprehensive plans to improve the country’s sluggish economic growth. The 1958 report made it clear that a paternalistic government would pick winners by selecting those industries it deemed to have the best potential for contributing to the New Zealand economy. The chosen would receive financial assistance.15 Over the next twelve months an Industrial Development Fund was established with £11 million in foreign exchange held at the Reserve Bank for allocation to promising projects.16 This was the forerunner of the Development Finance Corporation established in 1964, which in turn spawned the Small Business Agency in 1976. In a world where credit was so rigidly controlled because of the dangers of over importing, the Government had to find a way to assist those believed most likely to boost export receipts. Complexity seemed always to beget further layers of complexity.

Holloway and Sutch worked closely together. In a speech in January 1958 entitled ‘The Part to be Played by New Zealand Industries’, Holloway talked of the need to develop New Zealand’s raw materials. He used Labour’s familiar calls for more work, for sacrifices and for buying New Zealand-made goods. Woollen mills, footwear, furniture, and leather-producing industries were singled out, while engineering industries were told to make better use of their machinery. Holloway hinted at coming reductions in the importation of food items, signalling that New Zealand food producers should be prepared to take up the slack.17 Meantime, Sutch urged industries to make better use of his department’s expertise. He noted that many industrial units that had developed since 1936 had been unduly dependent on imported raw materials. As a consequence, the local ‘added value’ component of industrial production had remained steady as a percentage of GDP.

The kind of manufacturing that developed in the past has in some ways made New Zealand even more vulnerable to external fluctuations…. The need is for development of a sort that can reduce excessive dependence on fluctuating exchange receipts; that can earn overseas exchange; or that can make substantial exchange savings possible. The need is not only for a defence against threats to the standard of living. There is need for a positive approach which will lead to even higher living standards, for these standards are themselves continuously in jeopardy.18

Sutch’s opposition to the earlier policy of fostering import substitution industries was acceptable to Labour, as was his new policy called ‘manufacturing in depth’. The new theme song was sung lustily to the 100 delegations attending the Industrial Development Conference in June 1960. On that occasion Sutch restated the problem that had been at the heart of the conference on Economic Stabilisation in 1953. It was the same one that had worried Gibbs in 1951, for which Gibbs had a more market solution. Sutch declared that ‘while the social security and full employment policies are stabilising elements for internal economic life, their very constancy ensures a high level of demand whatever the balance of payments. The more generalised the living standard and the more constant the availability of jobs for all, the more difficult it is to do without exchange control and import selection.’

The problem, as Sutch saw it, was that ‘rigidity’ had been introduced into a most vulnerable and ‘precariously based economy’. The solution, in Sutch’s view, lay in more government intervention, not less. No believer in the ‘global village’, Sutch told delegates that free access to markets and the free flow of capital based on competitive private enterprise ‘will be a concept for the history books’. He had no confidence in the GATT. While private enterprise would play its part in the late twentieth century, international competition would ‘increasingly have behind it the power of the State’. New industries would be based on the most up-to-date developments. Central direction was vital to this future. Developing new markets, ensuring greater skills within the workforce, initiating major industrial projects, and channelling investment into them were all vital elements of his command-style economy.19 This vision was acceptable to many on New Zealand’s political left. The Christchurch-based New Zealand Monthly Review, which was launched in 1960 by several survivors of Tomorrow, became a mouthpiece for the Sutch doctrine.

Neither Sutch nor the political left in New Zealand was acting in a vacuum. What Robert Skidelsky calls ‘collectivist creep’ was gathering worldwide momentum once more.20 Confidence in the capacity of planners to produce beneficial outcomes received a boost throughout the world from the achievements of Soviet scientists with Sputnik in 1957, from John F. Kennedy’s victory in the 1960 American elections and from the momentum which took Harold Wilson’s Labour Government to Downing Street in October 1964. Sutch was no more than collectivism’s evangelist within the New Zealand bureaucracy and Wolfgang Rosenberg at the University of Canterbury was its high priest in academic circles.21

Meanwhile, Holloway was showing himself to be an activist minister. The Cabinet Economic Committee in 1958 decided he should explore the potential of the Japanese market for New Zealand coal exports; three trial shipments left for Japan in September. The following January the Government assured Parliament that it would do ‘everything possible’ to establish a long-term coal business with Japan.22 Investigations were undertaken into the economic advantages of laying an electricity cable between the South and North Islands to transfer the South’s abundant supplies to the North where more than 70 per cent of the population now lived. In April 1960 the officials’ committee recommended that the costly exercise proceed.23 However, most other schemes, and there were 240 new or expanded projects with a capital investment of £74 million, were shrouded in some degree of secrecy for commercial reasons. Holloway conceded in Parliament in April 1960 that the Government was actively pursuing ‘about 12’ of them.24

Plans to build a cotton mill in Nelson were debated publicly. In July 1959 the chairman of Smith and Nephew Ltd, a British cotton-producing firm, visited New Zealand. After discussions with government officials and then with Holloway on 8 February 1960, Nash announced on 1 March, while opening construction on a revived railway connection between Nelson and the South Island Main Trunk, that a large cotton mill costing £4 million would be erected in Nelson. It would initially produce meat wraps, denim, drills and sheeting, and employ 300 workers. After several anxious months, during which Smith and Nephew had second thoughts, an agreement was signed on 12 August 1960, three months before the general election. The Commonwealth Fabric Corporation, as it was now called, was eventually to allow New Zealand financial participation in the project. The Government guaranteed that it would use import licences to ensure the corporation 80 per cent of the New Zealand market for its initial products until 1964, with a longer period for later products. Prices to be charged for goods were not to exceed ‘the fair average price … for such products at the time of the company’s first commitment’. Construction of the plant was the responsibility of private enterprise, but without the Government’s generous guarantees the scheme would not have reached this stage.25

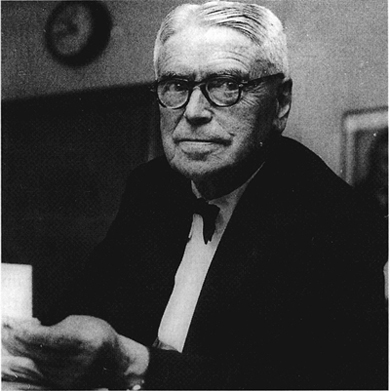

Arnold Nordmeyer, Minister of Industries and Commerce (1947–49) in the First Labour Government and author of the ‘black budget’ when he was Minister of Finance (1957–60). ATL C-23149

Another substantial industrial project was an aluminium smelter at Tiwai Point in Southland. On 19 January 1960 the Minister of Works, Hugh Watt, signed an agreement with Consolidated Zinc Pty enabling the company to construct a plant that would process bauxite imported from Australia. Part of the deal was that the company would construct a large hydroelectricity project at Lakes Manapouri and Te Anau. In October 1960 the agreement was given legislative endorsement.26 Plans for an iron and steel industry, which had been the goal of the First Labour Government, were also being dusted off.27 Instead of developing the limonite deposits in Golden Bay, which turned out to be much smaller than initially thought, Cabinet on 13 October 1958 approved the establishment of a merchant bar mill to produce between 40,000 and 50,000 tons of steel annually from scrap. This led to Fletcher Holdings beginning work on the £3.85 million Pacific Steel venture at Otahuhu in 1960 with the assistance of loans from the Development Finance Corporation.28

Meanwhile, an interdepartmental committee of officials, which had been set up in October 1958, was looking into the longer-term development of the North Island’s ironsands deposits. In February 1959 it recommended a joint government and private company to undertake the ironsands research, although forces within the Ministry of Works, probably with Sutch’s backing, preferred ‘complete control’ to remain in the Government’s hands.29 Fletchers was also interested in this project and had invested much time and money in negotiations with West Coast Maori and in its own research. Both Sutch and Holloway, however, concluded that Fletchers, with its stake in Tasman and Pacific Steel, was overreaching itself. Although it was not announced policy, officials, and particularly Sutch, seem to have determined that no one concern should be able to become a dominant player within New Zealand industry. At a meeting on 30 March 1960 to announce the Government’s chosen partner in the ironsands investigations, it was revealed that 51 per cent of the private sector involvement was to be in the hands of Australian interests controlled by Kormans who had no background in steel. Fletchers and a South Island rival consortium attacked the plans vigorously, and according to George Fraser ‘the meeting ended in chaos, with Sutch alternating between screams and speechlessness’. Stories soon leaked out about the Government’s preference for overseas bidders.30 The plans had to be shelved and in June 1960 Holloway announced that the Government would entrust the necessary ironsands research to a wholly government-owned company, New Zealand Steel Investigating Co. Ltd, under the watchful eye of a board chaired by Auckland industrialist Woolf Fisher. The company was asked to make recommendations on structure, location, capitalisation, ownership and a programme for development of an ironsands steel industry.

While the Labour Government gained little kudos from its behaviour over steel, a considerable degree of momentum towards industrialisation was building up. The Industrial Development Conference in June received a great deal of publicity. On 24 April 1960 Nordmeyer had told a Dunedin audience that industry was to be brought under government control to an even greater extent.31 A few days later Holloway announced that the Government was prepared to build factories and lease them to private enterprise, especially in regions where employment opportunities were needed.32

All these developments were watched avidly by interested parties, the National Opposition, the press and traditional opponents of state control. The Christchurch Press vociferously attacked the cotton mill proposal, believing that it appeared likely to become a dangerous monopoly producing high-priced goods at a time when competition from Asian products was reducing world cotton prices. The Textile and Garment Manufacturers’ Federation, its members all themselves benefiting from import controls, set up a fighting committee to oppose the mill, fearing that its monopoly status would inevitably force up the price of locally made garments.33 The Evening Post complained that the Government’s plans for building factories meant more bureaucratic control, less freedom for entrepreneurs, and probably less choice for consumers.34 The Hastings Chamber of Commerce argued that high tax rates were stifling initiative. If they were reduced and the raft of controls that had built up over the years were dismantled, private enterprise itself could build factories and expand output where appropriate.35 While the National Opposition generally suspended judgement on the Government’s schemes, the party’s paper, Freedom, sniffed that Holloway’s factories would no doubt be built in marginal electorates.36 Notwithstanding this criticism that had more than a grain of truth to it, the Government pressed ahead and acquired land; by October 1960, 50 applications to rent state factories had been received.37

Meantime the fresh crop of Labour politicians who entered Parliament in 1957 were as enthusiastic as their ministers about expanding the role of government and protecting the economy. The new MP for Roskill, Arthur Faulkner, declared in his maiden speech that ‘social experiments are regarded as part and parcel of the New Zealand way of life, and that gives our people a passport everywhere’. His constituents wanted ‘a Government that will do something to develop this nation, and provide it with the opportunity of getting as close as it can to self-sufficiency’. Faulkner denied that the average person wanted ‘mollycoddling from the cradle to the grave’ but went on to assert:

He wants orderliness in his family life; he wants security for the farmers, the workers, the manufacturers, and, yes, for the importers as well. He wants some sense of assurance that when he is aged … a kindly State will provide for him a reasonable standard of living. The same can be said of the infirm, and of youth.38

Another new MP, Norman Kirk, declared his support for a social programme ‘which will promote the housing of our people, protect their health, and ensure full employment and equal opportunity for all’.39 R. J. Tizard acknowledged the changing trade environment in which New Zealand was now operating and sought to use the good offices of the Government to promote trade in new markets. On an issue closer to his constituents’ pockets, he argued that the Government should control interest rates on hire purchase agreements.40 Michael Joseph Savage’s activist philosophy was still very much alive and in Kirk’s talk about ‘equal opportunities’ there was a hint of the later enthusiasm for complex social engineering that came to dominate the thinking of some within the Labour movement.

The Labour Government used old policy mechanisms in an effort to bring the 1957 exchange crisis under control. However, the promises from the campaign trail soon haunted members. Tax refunds and more government spending did not sit well with the economic realities of 1958. The income tax rebate to compensate for the movement to PAYE cost £21 million and the introduction of 3 per cent loans for housing (supplemented on 1 April 1959 by a new provision enabling the Family Benefit to be capitalised in advance) caused house construction to speed up.41 Labour’s Minister of Housing, Bill Fox, increased the rate of state housing once more, often in marginal electorates; critics called the products ‘Fox’s boxes’. With all this activity came bigger demand for imported components. Early in 1958 Nordmeyer sought to increase the ratios which trading banks had to invest with the Reserve Bank and in his budget on 26 June 1958 he felt it prudent to take, as well as give. While many welfare benefits as well as universal superannuation were increased, Labour emphasised its support for families by lifting tax rates for working couples without families and for single people. The level at which people began to pay income tax was reduced from £375 to £338 for the 1958-59 year, and to £300 in subsequent years. The top marginal income tax rate, which had been reduced by National in 1954, remained at 60 per cent, and for companies 67.5 per cent. Duties on beer, cigarettes, petrol and cars nearly doubled and Estate and Gift Duties increased.42

Nordmeyer’s ‘Black Budget’ removed any remaining sheen from Labour’s election promises. The fiscal crisis saw unemployment top 1000 early in 1959, in spite of the Government’s special work programmes in Forestry, Post and Telegraph and Railways and a cut back to immigration. It was the highest level of unemployment since the war, although there were still more than 6000 notified job vacancies. Nordmeyer loosened the purse strings when export prices improved at the end of 1958. In the last half of 1960, both government spending and bank lending reached high levels despite another slump in export prices. This produced a trade deficit in the year to June 1961 of £58 million.43 Public Service Commission employees, including temporaries and casuals, reached 62,000 in Labour’s last year.44

However, the boomlet was too late; Nordmeyer never lived down his ‘Black Budget’. John Marshall later called it ‘white hope’ for the National Party.45 The impression had become deep rooted that Labour was led by puritans who stood for austerity and a return to wartime regulations and controls. Since the parties differed so little in their goals and methods, politics had become a battle of perceptions as much as realities. With television beginning its first broadcasts in June 1960, the run-up to the general election on 26 November 1960 was the first in which New Zealand’s leaders had to project themselves on screen. None found the medium easy, but Labour fared worst. Nash by this time was nearly 79 years old. His opponents had a bigger war chest and were much better organised. Labour lost seven seats to National. Keith Holyoake’s rejuvenated National Party was back in office for what was to be a twelve-year reign.46

Once more Labour ministers had stepped up the level of government involvement in the economy and once more their National successors had to come to terms with their inheritance. Harry Lake, the new Minister of Finance, regarded by his colleagues as solid and conservative and by his opponents as dull and uninspiring, was immediately faced with the now familiar run on foreign exchange. Trading bank advances were tightened, an internal loan of £10 million was raised and Nordmeyer’s extra import licences of 1960 were suspended. Money for overseas travel which had long required permission from the Reserve Bank became even harder to get. State housing was wound back and the rules governing State Advances housing loans tightened. In his budget on 20 July 1961 Lake told Parliament that ‘we are attempting to do more than we can achieve with the resources available’.47 The ‘start-stop’ routine was becoming such a regular feature of New Zealand’s political economy that the Monetary and Economic Council and its chairman, Frank Holmes, began arguing for extending the term of Parliament from three to four or even five years to enable ‘longer term planning’ and a higher rate of growth. The Council believed that faster growth was essential given the expectations that New Zealanders had of their government.48

A signal that Holyoake’s Government intended to continue with ‘steady expansion of industry by private competitive enterprise’, as National’s manifesto had promised, came with Lake’s announcement on 17 April 1961 that New Zealand was to lodge a formal application to join the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation. By this time New Zealand was the only Commonwealth country that was not a member. Treasury had tried to convince National’s ministers in the early 1950s to join the fund and in 1956 told Watts that with the London loan market contracting, World Bank loans looked to be the only prospect for development capital at competitive rates for large schemes such as Tasman Pulp and Paper.49 Watts vacillated, and the Labour Government, despite Nash having favoured membership at the time the fund was established in 1944, opposed joining on vaguely anti-American grounds. Newspapers were divided on the issue.50

Keith Holyoake, Prime Minister 1957 and 1960-72, opens the Bowen Street State Building with his Minister of Works, W. S. Goosman, 1961. Evening Post

Lake set out the implications of IMF membership in a white paper.51 Few can have read it, for the decision produced a storm. As Keith Sinclair describes it, ‘anti-American leftists, anti-American funny-money men, Social Creditites and economic troglodytes in general’ petitioned Parliament against the National Government’s decision.52 Rosenberg produced a tract opposing membership, arguing that New Zealand’s full employment stemmed from its capacity to insulate itself against sinister world forces that would seek to interfere in the New Zealand economy, force it to abolish import controls, and accept a level of unemployment. He followed this up a few years later with a vitriolic attack on the growing levels of foreign investment in New Zealand, arguing instead for a greatly expanded role for the Development Finance Corporation as a laundering agent for the overseas investment needed for industrial expansion.53 The devotees of insulation were becoming worried that New Zealand’s faltering economy was being used as an excuse to internationalise it. This opposition to government policy was all posited on the assumption that it was possible to prevent internationalism.

The Government marched on. Having joined the fund to avail itself of the necessary credit, National’s ministers did not accept uncritically every recommendation by the World Bank. Nor did the Government stick with every expansionary scheme inherited from Labour. Towards the end of 1961 the cotton mill came under intense attack, led principally by Samuel Leathern, President of the New Zealand Textile and Garment Manufacturers’ Federation. Leathern told an Auckland meeting that the cotton mill agreement gave the mill monopoly status protected by import control and customs duties in those types of fabrics it chose to make. ‘We can understand the granting of temporary monopoly privileges to enable an infant industry to get on its feet. We … are utterly opposed to the granting of permanent monopoly to anyone.’ At a time when New Zealand manufacturers were selecting more than 500 different designs from overseas samples of cotton each year, Leathern argued that the range of 100 new designs which the mill would produce would lead to a ‘kind of austerity’ that would incite New Zealand women to march on Wellington ‘with rolling pins in their hands’.54 Nash disputed some of these claims about his cotton mill agreement,55 but Jack Marshall, the new Minister of Industries and Commerce, after initially indicating an intention to proceed with the mill, had second thoughts. He announced in January 1962 that the company’s offer to withdraw from the agreement would be accepted. However, there was to be compensation from the Government for the company’s expenses to date. This eventually cost the taxpayers £1.4 million.56

Cartoonist Lonsdale features the EEC wake-up call for New Zealanders, 1961. Auckland Star

Other major development schemes met with happier outcomes. The Cook Strait Cable was built and the aluminium smelter at Tiwai Point went ahead. However, in 1961 Consolidated Zinc found that the cost of constructing the necessary electricity generating capacity was beyond it. Holyoake’s Government was convinced that the smelter was economically sound so it accepted responsibility for constructing the largest power plant in New Zealand.57 The first aluminium was produced in April 1971. The pricing agreement for electricity has been in and out of the news ever since because of a perception that the initial agreement was too generous to the company, soon known as Comalco. Threats were made by the Muldoon Government in 1977 to impose higher prices on Comalco by legislation. Many years later Marshall, who was Minister of Industries and Commerce at the time of the 1963 amended agreement, claimed the Bluff smelter was ‘a jewel in the crown of New Zealand industry’ because of the earnings of overseas exchange from the plant.58

F. P. Walsh (President of the Federation of Labour) on the right, talking tough, accompanied by K. M. Baxter (Secretary) in the hat, May 1961. ATL, Dominion Collection, F-456741-1/2

Progress towards erecting a steel mill using New Zealand’s iron sands was steady, if not spectacular. After gaining much help from American consultants, Fisher’s investigating team reported favourably in December 1962. Further investigations resulted in a recommendation to Marshall in December 1964 that the Government become a ‘substantial shareholder’ in a mill. To be sited on the north side of the Waikato River mouth, the mill would process west coast iron sands using New Zealand coal. The report suggested that the steel could ‘make an important contribution to the balance of payments by saving exchange’. It would be marketed at a price ‘matching the average of prices for steel products from the United Kingdom, Australia and Japan’.59 In March 1965 plans were approved by Cabinet for the erection of a steel mill at a different site to the north -Glenbrook, on an arm of the Manukau Harbour. The Government purchased the land and took responsibility for railway connections and housing, just as it had at Tasman. New Zealand Steel Ltd was incorporated on 26 July. The Government agreed to subscribe up to 25 per cent of the shares in the company, and D. W. A. Barker, now Secretary to the Treasury, and M. J. Moriarty, now Secretary of Industries and Commerce, joined four private sector directors in the new company chaired by Sir Woolf Fisher.60 By this time the Government through its departmental involvement with the project had contributed a large, unquantifiable share of the investment.

Minhinnick pictures Walsh of the FOL, Holyoake and the New Zealand worker negotiating a wage round in 1963. NZ Herald

As with Tasman, the Government hoped that private investors would flock to take up shares in the company. They did not. This was partly because the Government decided to restrict foreign ownership to 20 per cent of the shares. This decision reflected the growing public paranoia about foreign participation at a time when many felt that further insulation of the New Zealand economy was both necessary and feasible. Another factor counting against the project was continuing doubt about whether New Zealand Steel could ever be a financial success. In 1968 the World Bank report on the New Zealand economy praised Pacific Steel but suggested that production runs were unlikely ever to be on a sufficiently large scale to be economic.61 These developments eventually led the Government to take up 46 per cent of the shares in the new company. The following year the Minister of Finance guaranteed $4 million worth of unsecured bonds, the money being used to fund a mill to produce steel pipes. New Zealand Steel made its first galvanised steel from imported black coils in November 1968 and its first billets of steel from iron sands the next year. The iron-making process was not perfected until 1973; production expanded steadily after that. Doubts about the mill’s viability continued to plague it. However, the Muldoon Government during the years of ‘Think Big’ ignored much contrary advice from officials and lifted the State’s investment in New Zealand Steel, in effect throwing good money after bad. After the Labour Government was obliged to accept responsibility for debts in a complex restructuring of the mill in December 1985 the enterprise was readied for sale. It was sold to the tottering Equiticorp empire in October 1987 for $328 million. By that time more than $1 billion of taxpayers’ money had been wasted on the enterprise.62

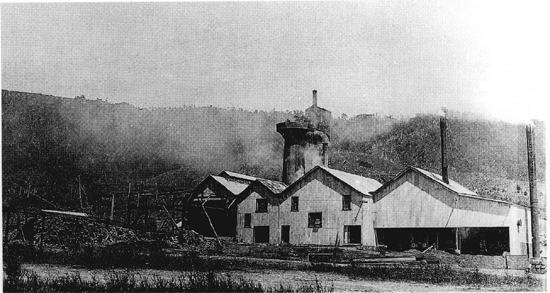

Onekaka’s private steel mill, Golden Bay, producing pig iron in the 1920s.

From earliest times the steel mill was plagued with bad industrial relationships stemming largely from the fact that there were too many unions engaged in a war for coverage of workers. Marshall claimed that the mill contributed much to New Zealand’s infrastructural developments.63 Yet the persistent talk in 1997 about the possibility that its latest owners, BHP, might be obliged to close it raises doubts about whether such an ambitious piece of technology in a small country like New Zealand would ever have begun, let alone survived, had it not been for huge state support.

The mostly state-funded New Zealand Steel mill at Glenbrook, 1987.

Of more significance than any of these developments was the visit paid to the Prime Minister by J. B. Price, Chairman of Shell-BP-Todd Oil Services Ltd in October 1961 to tell him that the company had found natural gas in commercial quantities in Taranaki. A few days later on 18 October, Price told an officials’ meeting that while they had not yet discovered much oil, the Kapuni gas field near Eltham and Hawera was ‘most encouraging’. It contained both gas and condensate and at a rate of usage of 100 million cubic feet per day could have a life of 30 years.64 Private exploration, which had already cost £5 million, was continuing at a cost of £30,000 per week. Politicians and officials were immediately seized of the magnitude of this news; in time it was to transform Taranaki and the port of New Plymouth and to impact on every aspect of New Zealand’s energy use. There was soon talk of reticulating gas to many cities in the North Island.

While a private consortium had done the initial investigations, ministers were soon directly involved. At the very least the Government intended to regulate the industry and it was generally expected that it would become an investor in some parts of the infrastructure. Representatives of Taranaki local authorities saw Holyoake on 11 June 1962 to request protection for locals from ‘the exploiting oil companies’ and also to seek concessional gas prices for the region so as to attract downstream industry or a 5 per cent royalty for the region from all gas produced. The Government demurred.65 On 28 August 1962 Holyoake informed the consortium that the Government intended to provide ‘any reasonable assistance’ to the industry. If the gas could not be used in a petro-chemical industry then the Government would negotiate to purchase it for electricity generation which would be needed when existing hydro generating capacity reached peak demand. Holyoake added cautiously that it all depended on price: ‘I am sure you will appreciate that no government could commit the country to such an undertaking unless satisfied that the price is fair and that the return to your own company is not more than is reasonable having regard to all relevant circumstances’.66 In December 1962 the Petroleum Amendment Act was passed which dealt with refinery licences, gas pipelines and the need for ministerial authorisation for them. The Act set up a Commission of Inquiry to consider applications and it granted rights of entry to land for exploration.67 Consultants were soon appointed to advise the Government and feasibility studies on pipelines were undertaken. Marshall was probably right when he wrote 25 years later of ‘a quiet industrial revolution’.68 The National Government drove much of it.

National’s boldness on the industrial front continued to be matched by a willingness gradually to expose New Zealand’s economy to the wider world. The driving force seems to have been the realisation that industrial promotion required overseas capital and expertise – often Australian and American – plus Australian raw materials for the smelter, and Australian markets for newsprint. Growing unease – Lake called it ‘apprehension’ in his 1962 budget – at Britain’s determination to join the EEC drew Australia and New Zealand closer. While there had been tariff agreements with individual Australian states in the 1890s and a number of tariff reductions in 1922, followed by a further agreement in 1944, it was Nash’s Government in August 1960 that agreed to the establishment of the Australian-New Zealand Consultative Committee on Trade.69 Marshall stepped up the pace of bilateral discussions.70 Sutch and the political left in New Zealand saw a closer relationship with Australia as a breach in New Zealand’s perimeter fence against the world. ‘Australian industries can at all times oust most New Zealand industries in their present stage’, declared Rosenberg, as he argued for tighter, not looser protection.71 Frank Holmes, however, who soon took employment with Tasman Pulp and Paper, and similar minds within Treasury argued strongly for closer ties with Australia, especially in forest products. Both governments realised that cooperation was in their mutual interest. Eventually in July 1965 the New Zealand-Australia Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed and it took effect from 1 January 1966. It was a partial agreement, limiting free trade to some raw materials, manufactured goods and a few agricultural products. However, New Zealand’s manufacturers wailed about potential threats to their viability. When the heat evaporated, Marshall told them that their ‘unreasonable, pig headed and obstructive opposition’ had enabled him to negotiate rather more safeguards for them than would otherwise have been possible.72 New Zealand was slowly being drawn towards the wider world.

Holyoake’s National Government seldom rushed things. Political scientist Robert Chapman observed that between 1960 and 1972 the Prime Minister’s greatest feat ‘was the slowing down of every process which, if speedily dealt with, might have represented change and political harm’. Holyoake himself liked to use the expression ‘Steady does it’.73 As in other countries, when it came to dealing with the regulated domestic economy, little changed. Tariff reform, which had been moving along at glacial speed in the 1950s, finally resulted in a new tariff regime and a Tariff and Development Board to monitor the schedule from 1 July 1962. Although ministers kept saying they preferred tariffs to import controls, they kept both after the new schedule came into force. Licences were traded from time to time and in 1965 there was an unseemly political row in Parliament when accusations were levelled that J. S. Meadowcroft, President of the National Party, was trading in import licences. Critics of import controls hammered away at them; Frank Holmes stated in July 1968 that ‘New Zealand [has] erected over the years many barriers to expansion by efficient enterprises and many props for the support of the relatively inefficient. Almost certainly the most important of these is our system of import licensing and exchange control.’ The Tariff and Development Board engaged in costly hearings to review the level of protection enjoyed by thousands of small and large industries. They usually resulted in decisions to retain the status quo.74 The system kept being defended by Industries and Commerce as essential to guarantee new industries a sufficient share of the New Zealand market. Having said this, officials acknowledged that protection introduced ‘commercial rigidities inconsistent with the attainment of the fullest efficiencies in production’.75 In 1963 an Export Incentive Licensing scheme whereby exporters had their existing import licences topped up with bonus import licences was introduced. This measure was part of the focus on exports that culminated in the Export Development Conference of that year.76 The Prime Minister believed that there was political kudos to be gained from licensing and asked Marshall for details about licences before visiting marginal electorates in the run-up to the 1963 election. National Party members, however, disliked price controls, although Sutch championed them. The system retained some political usefulness; when sugar prices rose in 1963 Holyoake asked Marshall to consider price control.77 Manipulating controls for political effect, as with so many other aspects of policy, was part of New Zealand’s woof and warp.

The National Government’s trade policy consisted of what Paul Wooding calls ‘a system of layers put down at intervals over time without consideration for its overall structure’. At the bottom was a set of tariffs on which was built an import licensing system which, in turn, had another layer of export incentives added to it in 1963. Then came the limited free trade arrangements with Australia from 1966. The result, says Wooding, was ‘a highly uneven pattern of effective subsidy to economic activities, an average level of protection high by comparison with OECD countries and a high degree of dependence on import licensing which made estimating the levels of protection very difficult’. Like many aspects of social policy, each addition to trade policy was a creation of the moment and was laid down with little thought to its impact on the existing mosaic. The policy was expensive: some parts depended on subsidies, while little revenue was gleaned from tariffs.78 Put together with other controls, Holyoake’s trade policy continued to drive up New Zealand’s cost structure and impeded the growth of internationally competitive industries, as the World Bank noted in 1968. Every time costs rose, prices increased, and wages were dragged with them.79

Not surprisingly, tax levels remained high throughout the 1960s. In 1968 the top marginal income tax rate was still 60 per cent but it was payable on income earned over $7,200 pa, which was a high income for the time. Lake decided in 1966 on another review of taxation and a six person committee chaired by L. N. (later Sir Lewis) Ross produced a detailed report in October 1967 which noted that New Zealand collected a high proportion of its tax revenue from direct taxation and that its rates of corporate taxation were extremely high by world standards. Ross recommended a flattening of income tax rates to provide incentives for work and a partial shift to wholesale taxes, with improvements to welfare benefits to compensate low income people who could find themselves initially disadvantaged. Rather than a blanket tax on goods and services, the Ross Committee suggested a wholesale tax on luxury items such as motor vehicles and alcohol at between 20 and 40 per cent, exempting ambulances, fire engines, buses and earth-moving equipment altogether. It recommended an 8 per cent tax on all consumer goods, as well as on a selected range of services such as overseas travel, drycleaning, hairdressing, motels and restaurant expenditure.80 It was both a far-sighted and judgemental review, reflecting the social attitudes of its time. As with so many reports over the years, the Government adopted some recommendations and ignored others. Taxes in New Zealand remained high and there was little willingness to shift towards sales taxes, mainly because at the time the report was released inflation was increasing.

Labour market developments during the 1960s tended to lock the Government and employers into higher costs. National had talked in 1957 of establishing an inquiry into what many supporters believed to be waste in the public service. Nash’s Government rejected the suggestion but on returning to office in 1960 the National Government established a Royal Commission under the chairmanship of Justice Thaddeus McCarthy. The report presented in June 1962 did not produce the sort of findings that many Government supporters hoped for. It studiously avoided making any judgements about the efficiency or otherwise of the service or its staff and was criticised for its inability to penetrate beyond the facade of many departments. One commentator called it ‘an exercise in culture-bound model-building’ and expressed disappointment that the report, which recommended the establishment of a State Services Commission (SSC) to replace the old PSC, did not also suggest a form of open, direct instruction about government policy to the SSC. Moreover, instead of reducing the 41 government departments now in existence, McCarthy suggested another two be established. Nor did the report recommend the flexibility in staffing arrangements that some observers thought essential to a modern service.81

An Advisory Committee on Higher Salaries soon began trying to establish ‘fair relativities’ with private sector positions, awarding significant increases to top public service salaries as it progressed.82 But since there was no slide rule run over departments in any systematic way to see whether payrolls could be pruned, the exercise simply added to mounting costs. Meantime, Labour’s moves to introduce equal pay for women employees in the public service, which came in three steps after 1961, also added to the ballooning costs of government. A further Royal Commission report in August 1968 on salary and wage fixing in the State Services, again headed by McCarthy, was no more robust in its analysis.83 New Zealand had developed a rapidly expanding bureaucracy equipped with rules for remuneration that guaranteed escalating costs. The Government was in no mood to chance radical reform. Cabinet decisions in 1968 to trim departmental functions deemed superfluous were easily reversed.84

Employment within the private sector experienced the same rigidities. In his discussion of industrial relations between 1946 and 1967 John Martin refers to the ‘corporatism’ that had developed during and after the war that ‘locked in the existing system’; vested interests on both sides saw little need for change.85 Election promises by the National Party to abolish compulsory unionism came to a climax in 1961 with the introduction of an I.C.&A. Amendment Bill. There was considerable opposition to abolition from the New Zealand Herald. While compulsory unionism seemed to many to be a denial of freedom of association, it had proved its worth by assisting the Government to crush striking unions in 1951. In the end the 1961 Act was a compromise which enabled compulsory unionism to continue where it was negotiated as part of an award.86 Union membership continued to grow.87

During the 1960s the Arbitration Court was increasingly reduced to its wage-order function; issues that threatened to become troublesome were taken directly to the Secretary of Labour or to the Minister. Tom Shand, Holyoake’s Minister of Labour in 1960-69 was a big, tough, independent individual. ‘Our object is to have peace – a fair peace, not peace at any price’, he told his first press conference in December 1960. ‘I hope they didn’t choose me just because I could be tough.’88 His bluntness and honesty appealed to the unions; Tom Skinner, later President of the Federation of Labour, described him as ‘an outstanding Minister of Labour’, which meant in practice that Shand was pragmatic and usually came to see things from the unions’ point of view. Yet employers also respected Shand and he seems to have been the only one who occasionally had reservations about what was happening under his stewardship. In reality, industrial relations were being centralised to a greater degree than ever before.89 It seemed politically easier to step in whenever there was trouble and to try to defuse a crisis before it developed. This practice resulted in many more threats of strikes than a decade earlier and generally softer settlements. The Government did not have the same incentives as private sector employers to hold out against union threats. Employers, depending as they did on the Government for so many things, usually accepted settlements that were beyond what they had planned for. In the protected environment that still existed in the 1960s, costs were simply passed on to consumers. As John Martin observes, ‘the fundamental problems in New Zealand’s system of industrial relations remained untouched’.90

A good example of what Muldoon called ‘the unholy alliance’ between unions and employers occurred in June 1968. The Arbitration Court responded to an application from the union movement for a 7.5 per cent wage rise with what came to be known as the ‘nil general wage order’. Nationwide confrontation threatened. The Government supported the employers’ and unions’ decision to take the issue back to the court. Both sides now agreed to a 5 per cent rise, with only the judge dissenting from the majority decision. While the outcome maintained industrial peace the court’s reputation, in Marshall’s view, had been lowered still further. Tom Skinner, President of the Federation of Labour from 1963 to 1979, agreed with this analysis.91 Unions realised that by direct pressure on employers, wage rates could be obtained above any award. The Government was soon witnessing an escalation in wages that added fuel to imported inflation.

Opinions in favour of freeing the economy from controls, and any government moves in that direction, were always controversial. Holloway spoke of the frustration felt by all politicians with a concern for the future when he told a 1963 conference on manufacturing that ‘there can be no co-ordinated efficient development without the tacit consent of the public as a whole. This is necessary before politicians will lead, or those who would work to stop progress can be restrained…. Can we really say that most people are interested in the future, or have they been soothed with the syrup of complacency?’ The previous three decades, he suggested, would come to be known as the ‘thirty easy years’. No politician, it seemed, was prepared to act, before first seeking a consensus.92

The subsidence of the New Zealand economy from the middle of the 1960s froze rather than liberated initiative. Fear was in the air. Sectional interests became more strident in their demands. Problems were things for governments, with whom voters still felt something akin to a contract, to wrestle with. This thinking dominated the wider world of commercial relations as Harold Wilson in Britain and Lyndon Johnson in the United States encountered mounting difficulties. Paul Johnson notes that state intervention grew in all parts of the globe when world trade began to subside.93 Interventionism had become locked into the national psyche. Politicians had designed the system that was in trouble; they accepted that it was their responsibility to try to fix it.

New Zealand’s eternally vulnerable economy was one of the first to suffer. There was a pre-election spend-up in 1963, and another in 1966.94 Net overseas assets of the banking system trended downwards after reaching a peak in the middle of 1964. This reflected a slide in export prices that became serious when the bottom fell out of the wool market at the end of 1966. Lake restrained credit sufficiently so as not to harm National’s reelection chances in November. By this time, however, there was considerable public discontent; it did not switch to Labour, which had adopted an unpopular stand against New Zealand’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Instead dissatisfaction with National made its way across to Social Credit. They won 14.5 per cent of the total vote and their first seat in Parliament (Hobson) but National retained office. Holyoake pronounced the economy to be ‘in good heart’ but export prices for meat, butter and fruit sagged. On 10 February 1967 Lake’s credit squeeze was intensified. Subsidies on wheat, flour and butter were abolished, reducing the outlay on food subsidies from $37 million in 1966 to $17.8 million in 1968.95 The milk-in-schools programme that had existed since 1937 was abolished to squeals of outrage from Labour. State house rentals increased and Post Office and rail charges rose. State Advances lending on new houses was curtailed and hire purchase regulations tightened. The family benefit increased as part compensation.96

R. D. Muldoon (Minister of Finance 1967–72, 1975–84), seated second left, and Jack Marshall (Minister of Industries and Commerce 1960-69), seated centre, surrounded by senior civil servants and interest groups at the first meeting of the National Development Council, March 1968. Evening Post

Harry Lake died suddenly on 21 February 1967. Two weeks later Holyoake appointed the 46-year-old Robert Muldoon to the Finance portfolio. He was a pugnacious, able cost accountant, whom university students soon nicknamed ‘Piggy’. In May Muldoon further restrained bank credit. Sales taxes on motor vehicles increased to 40 per cent and petrol prices rose. Roading construction slowed once Muldoon diverted much of the petrol tax to the Consolidated Fund. Alcohol and tobacco taxes were raised. Muldoon began what became his familiar trademark of selecting winners when he bestowed further incentives on the tourist and fishing industries and boosted tax deductions for manufactured exports. The result from these measures was a $90 million drop in import payments in the year to March 1968.97 In November 1967, several months after the introduction of decimal currency that had become identified with Muldoon, the Government took the opportunity of a 14.2 per cent British devaluation of the pound sterling to devalue the New Zealand dollar by 19.45 per cent. This gave a small boost to farm incomes and further deterred imports.

The employment scene changed rapidly. A shortage of labour in 1965 switched to unemployment of 6556 by 31 March 1968. Manufacturing production fell for the first time in more than 30 years. It was much the most serious economic reversal since the war. Despite more than a generation of encouragement to manufacturing, exports from that sector were uncompetitive in price because of the hothouse environment in which they were produced, and they contributed little to foreign exchange earnings. The World Bank pointed out that New Zealand was still largely dependent on the same narrow range of agricultural exports as in the 1930s. And farmers’ profits, as their organisations claimed, were slipping because domestic inflation kept rising at a faster rate than export receipts. In May 1969 one farming leader argued for another devaluation of the currency to boost farm incomes. Like Britain, the New Zealand economy seemed to be on a permanent downward trajectory.98

In this uneasy environment calls for a National Development Conference gained an audience. The goal was to arrive at some kind of consensus on how to accelerate growth. An Agricultural Development Conference had met in 1964.99 Throughout that year Sutch, who was regarded as an advocate of centrally driven, or ‘imperative planning’, had been pushing for a ‘National Efficiency Conference’ to discuss the quality of management, technical training requirements and the need for better labour relations in industry. Marshall demurred.100 In January 1965 the State Services Commission announced that Sutch would take early retirement from his position as Secretary of Industries and Commerce. It was widely believed that the Government had forced the SSC to act, although this was denied by the chairman, L. A. Atkinson.101 M. J. Moriarty took over as secretary but the thrust within the department towards more comprehensive planning continued. While staff numbers were back to 500, the prevailing international mood meant that departmental officers with plans had to be heard.102

Interest in planning and targets for growth went well beyond the bureaucracy. The Labour Opposition, several National Party branches, as well as the Manufacturers’ Federation, were discussing it. In 1968 the guru of American planning, John Kenneth Galbraith, visited New Zealand and gave a series of well-attended lectures celebrating the end of the market and the arrival of an age of planned industrial expansion.103 The Minister of Finance had already sought Treasury advice about the desirability of establishing a New Zealand planning organisation. Henry Lang, who took over as Secretary to the Treasury in 1968, replied with some details about the British experiments that began in 1962 with a National Economic Development Council, better known as NEDDY. Lang doubted whether New Zealand’s statistics were generally of a sufficient standard to undertake a similar planning exercise in New Zealand but added that in the agricultural area, where they were of a better quality, the Agricultural Development Council and the Agricultural Production Council had been able to set ‘indicative’ plans. These aimed at a growth rate of 4 per cent pa. When New Zealand’s statistical base had improved, Lang thought it would ‘be desirable to extend planning to other sections of the economy’.104

Industries and Commerce agitated while Treasury placated. Progress was slow. Treasury established an Economic Planning Section which met regularly while the department gradually built up its knowledge of experiments overseas. Officers concentrated on French planners who had developed the concept of ‘indicative’ planning which was taken up by Harold Wilson’s Government after 1964. Treasury favoured plans that would provide targets and statistics rather than engage in ‘imperative’ planning that conjured up images of the Soviet Union’s economy. Sutch and Rosenberg were seen to favour ‘imperative’ planning and were therefore marginalised from this intellectual process. Frank Holmes, then at Tasman Pulp and Paper, and Bryan Philpott from Lincoln College, both of them soon to be professors at Victoria University, as well as Jim Rowe of the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, were in close touch with Treasury’s unit. After 1970 Philpott’s department at Victoria University experimented with several elaborate models.105

The new version of ‘scientific’ planning slowly captured the imagination of ministers and top officials. If it were to be successful, planning could not be confined to industry leaders. All interested groups needed to identify consciously with any plan, its targets and efforts to influence the public. Wide consultation was soon being discussed. This process became an opportunity for many groups to advance gender issues and peddle a variety of other causes. Ministers started to realise that some of their freedom to act would, of necessity, be circumscribed; extra spending here or a soft wage settlement there could impact adversely on any plan.106 Yet, throughout it all, officials maintained a sense of humour. One parodied Henry V’s speech before Harfleur:

Once more into the breach, dear friends, once more;

Or close up – but first must we our objectives define….

Nor must we try to do too much too quickly.

But simulate the action of the tiger;

Coordinate the sinews, integrate the blood

With broad total expenditure programme levels…

Cry ‘God for the Target, the Planners – and the Plan!’107

Frank Holmes talked up the virtues of planning in speeches around the country and convinced the Chambers of Commerce in May 1967 to call for a ‘National Economic Council’ which would recommend a raft of further incentives for selected economic activities.108 Treasury, however, was beginning to feel that it was being stampeded into something that officials could not control. In April 1967 Noel Lough observed that the department had ‘neither the machinery nor the present intention to undertake such an exercise’.109 Yet Treasury was reluctantly obliged to inform Muldoon in June 1967 that ‘the tide was washing’ in the direction of planning and that ‘some form of an overall national planning advisory body is more or less inevitable in the long run’. Treasury doubted whether the exercise would be of much use but something good might come from allowing various sectors in the economy to air their views. Officials cautioned the minister, noting that under current conditions, where the Government’s measures to restrain the economy were beginning to bite, any national gathering ‘will be used as a means of pushing the claims of individual sectors and consequently putting pressure on Government’. This piece of foresight convinced ministers of the need to have all interests represented, so that no single group could dominate proceedings.110

Treasury was struggling to keep ahead of the play. Officials persuaded Holyoake to make soothing noises to the Chambers of Commerce, to defer any immediate action on planning but to signal that a National Development Council could well be established in due course.111 Early in 1968 the Government finally announced a National Development Council. A preliminary gathering was to take place in August which would be the forerunner to a plenary National Development Conference a few months before the General Election in 1969. Muldoon and Marshall made it clear to officials that they would be controlling the process. They would keep parliamentarians away from proceedings and possibly chair sessions themselves. On 3 March 1969 Cabinet duly endorsed this. It was decided that the National Development Council would be permanent. Six sector advisory councils (Manufacturing, Forestry, Fisheries, Minerals, Tourism and Fuel and Power) as well as the existing Agricultural Production Council, the Building Advisory Council and the Transport Commission would be represented on the NDC. Each sector was to maintain a direct line of communication with the relevant minister. The secretariat for the whole planning exercise would be located in Treasury, a piece of news that led a rather sour Dr Sutch to warn that the whole exercise was being designed to soften New Zealanders for a world of unemployment.112

Ministers had clearly decided that if interest groups were to have the conference they wanted, then they would manage proceedings, particularly if there were political benefits to be obtained. They cautiously let Lang, as Secretary to the Treasury, chair the early advisory council meetings and then when it became clear that the whole process was not going to be a disaster, Marshall decided to take over the plenary sessions of the conference.113

Meantime a great many academic papers about targets were produced, although debate continued amongst officials about whether the exercise was likely to produce useful results in the longer term. Professor John Roberts of Victoria University was sceptical from the start. Harbouring similar doubts to Treasury’s, he warned that unless a clear, authoritative central strategy could be agreed upon, each sector ‘may simply elaborate its demands for support to the point where the economy, far from being rationalised by the process … is led into a morass of competing demands’. He added that in his view, there were ‘substantial perils’ in institutionalising pressure groups. While means existed to prevent this happening, they required political will.114 Behind Roberts’s comments lurked a doubt that Holyoake’s Government, renowned for its reluctance to be decisive about anything, could muster the necessary elan to extract much from the planning process.

The National Development Conference met at Parliament in May 1969 with as much fanfare as the Government could orchestrate. Eddie Isbey, a leading trade union figure, called the exercise a Cecil B. de Mille extravaganza with a star-studded cast. Jack Marshall was awarded Oscars by the press for his competent chairmanship. The huge talkfest involved 600 people in sector committees and working parties. They passed 632 resolutions and agreed on a number of recommendations put before them by the targets committee.115 It was argued that a long-term growth target of 4.5 per cent pa required restraint on consumption, higher levels of savings, an increase in capital investment in the private sector and careful research and identification of new investment projects likely to produce a high rate of return. While some resolutions talked of the desirability of opening up the economy, almost every plea was for more state intervention.

Participants heard what they wanted to hear. Muldoon incorporated those recommendations he liked into his budget on 26 June 1969. The document contained new export, forestry and tourism incentives, further assistance to the Fishing Industry Board, more generous tax breaks for dairy, wool and industrial research and there were new depreciation allowances for meat processors. Further transport subsidies were provided for fertilisers. Successful farmers would be helped by State Advances loans to expand the size of their farms. Several significant changes to the finance industry were announced. National Development Bonds were launched, as well as an incentive savings bond scheme. Capital issues controls over finance companies were abolished, although the government stock ratio system, whereby financial institutions were required to hold a percentage of their borrowings in the form of government securities, took its place. However, merchant banks specialising in commercial financing were allowed to operate for the first time.116

In the aftermath of the conference an elaborate planning structure emerged. Sector councils serviced by various departments met from time to time, reviewed their targets and the progress made towards goals. They reported in September or October each year to a meeting of the National Development Council. Some groups complained at being left out of the consultation process; trade unions were irritated at having to operate through the existing Manpower Planning Unit within the Labour Department, while the universities seemed not to fit neatly into any sector council. Treasury’s planning division attempted to keep some form of control over the exercise. Confidence lasted for some time. In May 1970 the Listener published a full-page spread on the NDC explaining how the system was meant to work.

However, while a handful of academics praised the planning exercise, there were doubters even among them.117 It proved impossible to maintain the momentum of 1969,118 and rapidly rising inflation (it reached 10 per cent in 1970) and a flagging economy meant that the growth target of 4.5 per cent pa could not be achieved in the early years of the plan. Between 1970 and 1974 growth averaged less than 2.8 per cent annually. Frank Holmes tried to argue that the targets themselves were ‘artificial’, that 4.5 per cent should never have been agreed to and that the failure to achieve it did not necessarily mean that planning itself was a waste of time. But he could not stem the rising scepticism about the NDC, which was turning into an expensive exercise. Constant complaints from planners and bureaucrats about the inadequacy of New Zealand’s statistics forced Cabinet to approve another 33 officers for the Statistics Department.119

In the election of 1969 the Muldoon phenomenon was a force to be reckoned with. He was an aggressive, confident, self-proclaimed ‘counter-puncher’, who appeared always to know what he was talking about. He had learned to stare at his television audience straight down the barrel of the camera. Coupled with the NDC planning exercise, Muldoon’s confidence was enough to carry Holyoake’s Government to its last victory over a slowly rejuvenating Labour Party. What looked like defeat for National early on the evening of 29 November became a win by six seats, soon to slip to four when Tom Shand died two weeks later and his seat of Marlborough was won by Labour in a by-election. But National suffered the fate of many a government that has overstayed its time; Gordon Coates, George Bush, Paul Keating and John Major are just some of the other twentieth-century leaders who were elected when their parties had really run out of steam and who eventually paid a severe penalty. By the end of 1970 National was tired. The Prime Minister was in hospital and Muldoon’s bubble was bursting. There was talk of ministerial retirements, inflation ballooned and industrial unrest rose rapidly.120

Nevertheless, the public hoped that the omnipotent State could restore equilibrium. Farmers suffering from rising inflation but uncertain export returns sought and received a further raft of subsidies. On top of help to dairy farmers willing to switch to beef came drought relief in May 1970, further fertiliser subsidies, and the establishment of a Special Assistance Fund for farmers. Then came a Federated Farmers’ request in February 1971 for a ‘cost adjustment scheme’ involving as much as $100 million annually. It drew some tart remarks from Professor Ken Cumberland of Auckland University, who felt such a scheme would not provide farmers with the necessary incentives to diversify or to improve their marketing techniques. He labelled it a ‘degrading, shameless disaster’ designed to provide agriculture with ‘an artificially low cost structure so that it could stay where it had been for decades’.121 The Government did not fully accept the proposal but granted an extra $16 million to the Wool Board during 1971-72. A Stock Retention Incentive Scheme was also introduced. Norman Kirk, Labour’s leader, called it ‘a family benefit for sheep’. The scheme assisted 30,000 farmers and cost nearly $50 million in its first year. In the view of one Southland farmer it caused many farmers to over-estimate their sheep numbers.122 Many farmers were uneasy and spoke of self reliance but in reality big subsidies had become part of their lives.

Lurking behind most problems in 1970 was inflation. In an attempt to curb it the National Government announced a price freeze on 17 November. It lasted until a complex price-justification system took effect on 15 February 1971. Parliament was now summoned to pass a Stabilisation of Remuneration Act which set up a Remuneration Authority. Marshall, now Minister of Labour, sought to enforce existing wage agreements and to ensure that when they were renegotiated, increases did not exceed 7 per cent unless the newly created authority had given its consent. The FOL opposed the move and, as Tom Skinner later pointed out, the experiment did not work because employers fell in behind the unions and the 7 per cent maximum became a starting point for negotiations. Quite often it acted as a springboard for higher agreements. In May 1971 the Monetary and Economic Council warned against the ‘wage-price spiral’ that was developing and argued strongly that restraints were unlikely to remove the pressures that gave rise to them. Arch-regulators like Sutch wanted tighter controls and one professor advanced a case for taking wages out of the hands of employers and unions and placing them under the rigid control of an Incomes Board. In Conrad Blyth’s view, inflation and regulations had produced a situation where behind the scenes ‘a massive shift in the distribution of real wealth’ was taking place, ‘with the wide boys and smart cookies making money, and the suckers – and there are a lot of business suckers about – losing money, after you make allowance for inflation’.123 The Government picked and chose between competing bits of advice, preferring in the end to use old-fashioned controls with which it was familiar. Another price freeze was introduced in March 1972 and further regulations were gazetted under the Economic Stabilisation Act 1948. They were no more successful than the previous set, especially when Muldoon spent up generously in his budget of June 1972.124 Local authority rate demands rose by between 20 and 35 per cent in many parts of the country, threatening people on fixed incomes. The country was getting its first taste of sustained inflation. Soon there was an air of crisis, and of a government living from week to week.

Industrial unrest reached a level in 1971-72 that had not been seen since 1951. Many unions that had distanced themselves from the Labour Opposition during the 1960s, preferring to go it alone, began mending bridges. Norman Kirk, who had led the Labour Party since December 1965, gained pledges of support from trades councils in the run-up to the election of 1972. There was only one opinion poll between 1969 and the election of 1972 that did not show Labour in front.

The Governor-General, Sir Arthur Porritt, swears Jack Marshall into office as Prime Minister, February 1972. Evening Post

On 7 February 1972 Sir Keith Holyoake, as he became in 1970, resigned the prime-ministership. He was the third longest serving prime minister in New Zealand history, not far behind Seddon and Massey. His pompous demeanour masked a tough centre which enabled him to rule his sometimes disputatious ministers with seeming ease and good will. His Government, however, will be remembered more for the opportunities lost than for those it seized. His deputy, Jack Marshall, beat Holyoake’s preferred choice, Muldoon, in the ensuing National caucus ballot for the prime-ministership. But Marshall could not survive the mood for change which showed every sign of increasing, even as commodity prices rose throughout 1972. Using the slogan ‘It’s Time for a Change’, Norman Kirk’s Labour Party swept to office on 25 November 1972 with nearly 49 per cent of the vote and a majority of 23 seats in the 87-member Parliament. Once more the public had elected Labour to try to wring improvements from a highly regulated, centrally driven economy. But New Zealand was now operating within an increasingly volatile world environment.