By 1972 world trade had recovered from depression and war, and during the previous quarter century had grown at the remarkable average annual rate of over 7 per cent. Industrial production had rocketed up and standards of living had moved in the slipstream. During the late 1960s came signs that all was not well. The American stockmarket slowed and share values ceased growing altogether in 1968. Productivity figures subsided and inflation became a more serious international problem, driven in part by American intervention in Vietnam. In the years after World War II more and more Middle Eastern oil had poured on to the world market keeping energy prices low. Western economies as well as Japan became dependent on cheap oil. However, beginning in the early 1970s, Middle Eastern exporters moved to restrict the flow of oil in the hope of increasing profits from their greatest asset. Oil prices rose, and money began flowing away from the developed countries in what Paul Johnson notes was ‘by far the most destructive economic event [for the West] since 1945’.1 Developed economies entered upon a period of ‘stagflation’. From a quarter century of record growth, they slowed down to nil or, in some cases, negative growth by 1974-75. Unemployment rose steadily. By the early 1980s it reached levels that were unparalleled since the Great Depression. Because governments continued to spend big, inflation moved upwards.

Since few countries in the world were more dependent for their livelihood on world trade than New Zealand, not even its highly insulated economy could fail to be affected by these trends. In fact, New Zealand anticipated the world downturn. Its economic growth lagged behind the best world performers after the war, and slumped in 1965; over the next quarter century New Zealand’s average growth rate of 0.8 per cent per annum was almost the lowest of all its regular trading partners. Its inflation, however, was at the top end.2 The impact of slow growth and inflation on New Zealand’s welfare state was debilitating. The severity of the downturn, especially after the first oil shock in 1973, gave the collective anxiety that was observable everywhere within the western world a particularly sharp edge in New Zealand. This explains in large measure why citizens began rethinking the relationship between the people and the State earlier, and in a more sustained manner, than in many richer countries. Most experienced a changing tide; New Zealand suffered a tsunami.

Many New Zealanders were reluctant to accept an end to the golden weather. With the improvements in medical science the numbers of elderly grew; they formed pressure groups aimed at redistributing state spending away from younger people to themselves, on the grounds that their payment of taxes over the years amounted to a contract which had to be fulfilled. Politicians became more solicitous of the growing legions of older voters. However, there was increasing resistance to high levels of personal income tax being channelled toward those whose own resources, in many cases, meant they did not need state assistance. The rough and ready national consensus that viewed government as an instrument for the collective will and which had underpinned 30 years of welfare state and steadily rising expenditure began to crack and eventually to crumble. At the end of the 1970s political parties began to rethink their approach to the State’s responsibilities.

A wind-down in the welfare state could not have been further from Norman Kirk’s mind when he took office as Prime Minister on 8 December 1972. Born in Waimate in 1923, Kirk’s family had suffered the ravages of depression, unemployment and war. As an early biographer, John Dunmore, observes, poverty set limits on everything the young Kirk did.3 Leaving school at twelve, he taught himself several manual skills in a variety of jobs. He built his own house in Kaiapoi from bricks he made; he also read eclectically. After several years as Mayor of Kaiapoi, he narrowly won the seat of Lyttelton in 1957. He quickly made an impact in the House, where Walter Nash picked him as a future leader.4 Five years later Kirk was both president and leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party. Forceful in debate and occasionally intimidating, Kirk was head and shoulders above his colleagues by the time he became Prime Minister. He came to be revered like no other Labour leader since Savage. What influenced everything his Government touched was his premonition that he would not make old bones. Urgency to leave his mark can be read in every page of Labour’s extravagant 1972 Manifesto. The Prime Minister took it with him to Cabinet, caucus, the House, or briefings of officials, and would thump it vigorously while explaining his government’s intentions.5

The manifesto was probably the most paternalistic document in New Zealand’s history.6 Its authors showed complete confidence in the capacity of governments to intervene effectively in social and economic affairs and little appreciation of how the difficulties currently affecting New Zealand’s economy might limit its capacity to carry extra spending. In this regard there was a harmony of views between older and younger generations of New Zealand’s political left. Most of the seventeen new Labour MPs in Kirk’s caucus were between their mid twenties and early forties; they were self-confident products of a big spending era and inclined to think well of it. Many held tertiary qualifications. Some had been part of the revival of the left on campuses during the 1950s and 1960s and were stirred by foreign policy debates, the Vietnam war, a romantic search for an egalitarian society and a more carefully defined sense of New Zealand’s independent national identity.7 Frank O’Flynn QC was one of the older, and certainly the most illustrious, of the new intake of Labour MPs. He spoke for all of them when he said:

‘Taking up where Savage left off’: Norman Kirk, leader of the Labour Party 1965–74, photographed in 1966.

The aim of the Government is to give the people … the leadership that is necessary to rebuild [the] social system, to provide equality for all… citizens, an education system, and other assistance that will enable every citizen to develop his abilities to the full and play a proper part in society – to provide a social system that will take proper care of the young, the old, the handicapped, and the sick as a matter of right and justice, not as a matter of charity. The Government also intends to ensure that the nation once again plays a worthy part in world affairs and becomes a champion of the rights of small nations and of moral attitudes in international affairs.8

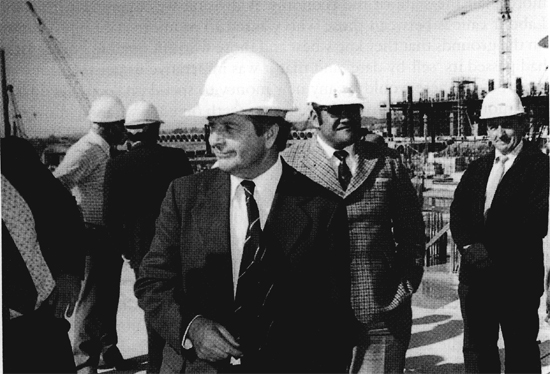

Norman Kirk after assuming office, December 1972. Huge expectations of a successful revival of state activism rested on him until his death on 31 August 1974. Press

The whole campaign of 1972 centred on the need to increase growth in order to improve standards of living. Kirk, who was Keynesian to the core, exuded confidence that a big-spending Labour Government would retrieve prosperity. To him, all problems resulted from a poverty of vision and imagination. Bold use of the Development Finance Corporation and the funds of a compulsory New Zealand Superannuation scheme which the party intended to introduce, would provide the necessary investment capital. This would be aided by a generous expansion of tax incentives and interest-free loans of up to 70 per cent of the value of new plant and machinery for selected industries. There would also be a raft of tax breaks for wage and salary earners.9 It was Sutch’s doctrine in neon lights.10

A detailed account of the Third Labour Government, as well as assessments of its effectiveness, has been published elsewhere.11 Higher export prices during 1972, especially for wool, created an air of anticipation that Kirk’s Government would be able to live up to its extravagant promises. In spite of a cautious Treasury briefing to the incoming government that warned against letting the belt out too far, Kirk announced that a special Christmas payment would be made to most beneficiaries. This kindled memories of 1935 and seemed a good omen. One Auckland sharebroking firm advised its clients in December 1972 that it looked forward to ‘a stable and expanding economy’.12 However, the rules applying to overseas investment were tightened in line with Labour’s suspicious approach to foreign investment that was not tied specifically to industrial projects. In January 1973 the new Minister of Finance, Bill Rowling, announced criteria to govern each application in order to ensure that it was ‘not excessive in relation to the benefits which New Zealand receives from this investment and that no overseas company is able to operate against the national interest’. Labour’s belief that it could insulate the country against the machinations of the wider world was still alive and well. This time, however, the Government would rely less heavily on import controls (although a great many continued to be used), and more on various forms of direct assistance ‘applied selectively’ to industry.13 In this, Labour foreshadowed the approach adopted by Robert Muldoon in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

When Parliament assembled in February 1973 it moved quickly to enact several spending measures. In order to provide better security for low-income people being threatened by rising property rates, a Rates Rebate Bill was introduced. The brainchild of Henry May, Minister of Local Government, it provided a set of rebates payable by central government. It was estimated to cost $5 million in its first year. In 1978 the scheme cost taxpayers nearly $9 million. Since the measure lifted some of the rates burden from the more vulnerable sections of the community, it had the side effect of freeing local councils from the need to be so careful with their spending. Local authorities had been benefiting from increasing subsidies since the 1870s. They received further help in 1973 with the creation of a Ministry of Recreation and Sport. It introduced a subsidy regime which councillors could direct towards community groups. There was talk of restructuring territorial local authorities to make them more efficient but in the end little more was achieved than the imposition of a regional tier of government. Since Joe Heenan’s efforts in 1946-47, governments had also been lifting their contributions to the arts; the Kirk and Rowling Governments between 1972 and 1975 more than doubled the total paid from the Consolidated Fund and the Lottery Board to the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council.14

On 14 June 1973 before a packed House and a gallery largely made up of young people, Rowling delivered his first budget in the knowledge that overseas reserves stood at a record $1 billion.15 He spoke of the need for ‘faster progress’ towards Labour’s goals and of the Government’s intention to restrain inflation during that process. He indicated that Labour accepted indicative planning but was sceptical about the NDC planning structure and was reviewing it. Government assistance would be channelled through a wholly government-owned Development Finance Corporation towards industries that already were, or showed the potential to become, internationally competitive. Repeating a phrase often used by Kirk, Rowling added that economic growth would ‘be regarded as the servant of our social needs and not as the master of our environment’.16 He took comfort from the fact that domestic consumption was up, that unemployment was falling and that there had been a big jump in the amount of overtime and shiftwork. This would now be subject to lower tax rates to encourage even more effort. Rowling intended to provide incentives for faster growth to underpin full employment and ensure a ‘fairer distribution of income’. Earlier in the year he had sought to dampen inflation by introducing a retention scheme for a portion of wool producers’ incomes. As part of the inflation control programme the Government intended to stabilise the cost of services directly under its control, such as Post Office, rail, and bulk power charges. This had been promised in Labour’s manifesto. Bigger subsidies would also be paid to hold down the domestic prices of sheepmeats, milk, woollen goods and sugar;17 fish prices were frozen; and a system of maximum retail prices was to be be introduced on a wide range of retail products. A Property Speculation Tax was signalled to curb land speculation that had begun in anticipation of a hike in centrally driven house building. There would also be a further range of subsidies – including concessionary rail charges for transport to and from the South Island, and more encouragement to industrial development outside the main centres.18

There was more to come as Labour sought to rush growth for social purposes. Rowling announced that new efforts would be made to promote tourism through the Tourist Hotel Corporation, which had been costing the taxpayer dearly for several generations. State spending on housing and electricity capital works would increase. Fourteen per cent more would be spent on education and 19 per cent extra on health. Most welfare benefits went up. A system whereby pensioners paid only half their telephone accounts began on 1 October 1973. This principle was extended on 1 January 1975 to television licence fees for income-tested beneficiaries. In a major announcement with consequences for the longer term that the minister cannot have imagined, Rowling promised a Social Security Amendment Bill that would add a Domestic Purposes Benefit to the large array of existing welfare benefits. A New Zealand Superannuation Scheme would also soon be the subject of legislation. An indication of the optimistic climate existing at the time came with the announcement that Rowling would continue the personal income tax rebate first introduced by Muldoon the previous (election) year.19

Kirk smiled paternally throughout Rowling’s long speech. The Prime Minister was clearly delighted with the magnitude of what his Government was doing in its first year. Rowling’s first Budget was a giant further step in social engineering, building on measures found useful in wartime. Labour’s belief that governments could successfully order the world in which people lived, worked and traded was at high tide. And it came at a time when the world trading scene was just beginning a high dive.

Kirk’s plans quickly lost their gloss. Wage pressures were now so high that Cabinet, then the Government caucus, were obliged to act on 9 August 1973. On the recommendation of the Minister of Labour, Hugh Watt, a wage stabilisation order of 8.5 per cent was announced. This figure was to be reduced by any increases negotiated since 1 February. However, there would be a further rise for public servants in October because of a complex ‘ruling rates’ analysis that gave them periodical top-ups. All pay increases were expected to hold for at least six months. As during the war, they would increase only if the CPI had risen by more than a set amount – in this case 4 per cent. Kirk promptly declared that an increase of 45 per cent in MPs salaries recommended by a Royal Commission would be put on hold,20 hoping thereby to lower popular expectations of further wage increases. He failed to calm industrial unrest. It raged spectacularly at the Tasman Pulp and Paper plant in Kawerau for some weeks and broke out in other places as well. The combination of a big spending budget, a large wage order and rapidly increasing import costs was pushing inflation along at breakneck speed, and well-positioned unions used their industrial muscle.

There was worse to come. Kirk received a jolt when he attended a Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Ottawa in August 1973. Besides establishing close relations with several leaders from Third World nations, he realised from general discussions the full extent to which world trade was slowing down and stock markets faltering, while inflation galloped ahead. Like Savage a generation earlier, he concluded that New Zealand could take further steps to insulate itself. ‘The overseas situation must be shut out as much as possible’, he told caucus on his return.21

Inflation showed no signs of abating. The public became anxious.22 So Cabinet decided to revalue the New Zealand dollar by 10 per cent on 9 September 1973 to lessen the impact on the economy from imported inflation. At the same time, the export of hogget and mutton was stopped in the hope that more supplies for domestic markets would reduce pressure on local prices. In case these moves did not succeed in restraining meat prices, a complex system of ‘reference prices’ for export meat was imposed from 1 November; overseas receipts above the reference price level would be diverted into a stabilisation fund to be used to ensure that meat prices were kept at an acceptable domestic level. Some fish destined for export was diverted to the domestic market and meatmeal and tallow exports were controlled to ensure that domestic prices did not force up consumer items such as eggs, poultry, pigmeats, cooking margarine and soap. Again there was talk about a system of Maximum Retail Prices (MRP). Since there was still adequate overseas exchange, some extra import licences were issued for consumer goods, including cars. Housing shortages would be tackled more enthusiastically with a mixture of state and private house building; those experiencing escalating private sector rents were urged to make more use of rent appeal authorities.23 It was a set of measures on a similar scale to the announcements by Fraser’s Government in December 1942. However, there were no quick solutions for rising oil prices. They shot up after the Yom Kippur war in October 1973. Arab producers decided to use oil supplies as a diplomatic weapon against Western countries that had, for the most part, supported Israel. Kirk urged New Zealanders to make more use of public transport.

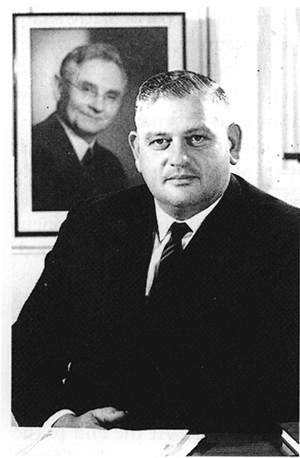

The downwards trajectory for New Zealand’s terms of trade 1950–89. From Graham T. Crocombe, Michael J. Enright and Michael E. Porter, Upgrading New Zealand’s Competitive Advantage, Oxford University Press, 1991.

The most difficult measure to implement was the price justification scheme being worked on by Warren Freer, the Minister of Trade and Industry (as the old Industries and Commerce portfolio was now called). With the cooperation of the Price Tribunal, Freer had been seeking to produce a system of public notification of ‘fair and reasonable prices’ since March 1973.24 What he hoped would take a few weeks to devise took another sixteen months. Complex discussions with officials, the Price Tribunal and manufacturers’ representatives centred on methods for determining ‘maximum distributive margins’ for use in calculating the final Maximum Retail Price.25 There were lengthy debates in Cabinet and caucus before MRP finally went into force on 1 July 1974. The process had taken so long to implement that many manufacturers had had to calculate, then recalculate, their costings for the figure to be placed on the indelible MRP shield printed on all regulated merchandise. Confusion surrounded the scheme from the start; many officials doubted whether it could ever be made to work. The Campaign Against Rising Prices, whose support Freer had anticipated, attacked it and sections of the union movement were becoming very unhappy with continuing high inflation, believing the answer lay in better wages, which they could win through direct action. The National Opposition ridiculed MRP and some manufacturers, as they always had, made money out of this latest effort at price control. The Government attempted to recalculate fair levels of pre-tax profit in the Stabilisation of Prices Regulations 1974, Amendment No. 2, promulgated in June 1975,26 but the cumbersome MRP scheme lingered and the Government looked inept.

Meantime ministers had been debating a growth strategy aimed at lifting the country’s performance above the average level of achievement since the war. Treasury argued for fewer controls in the belief that deregulation was more likely to produce the right environment for better growth; Trade and Industry, now led by the headstrong Jack Lewin, was adamant that with targets and planning better results were certain to emerge. Each department advanced its own viewpoint fiercely and eventually the Cabinet Policy and Priority Committee told them to reconcile their differences. On 8 May 1974 ministers expressed a general preference for assistance to the manufacturing sector but were vague on the specifics as to how this assistance should be extended. The minute of the meeting is wordy and ministers seemed genuinely baffled by the conflicting advice they were receiving.27

Labour’s unsuccessful efforts to control prices were partly overtaken by a substantial piece of legislation introduced in August 1975. The Commerce Bill’s long title gives a clue to its all-embracing intentions. It was to ‘assist in the orderly development of industry and commerce and to promote its efficiency, and the welfare of consumers, through the regulation, where desirable in the public interest, of trade practices, of monopolies, mergers, and takeovers, and of the price of goods and services’. Freer saw it as a vital part of the Government’s growth strategy. It would help to ensure fair competition in the marketplace and produce better outcomes for consumers. A Commerce Commission replaced the Price Tribunal. The commission had both inquiry and judicial functions, especially where mergers or takeovers were proposed. The National Opposition opposed the Bill vigorously, especially its wide regulatory powers. National argued that the legislation gave too many powers to the Department of Trade and Industry and was a ‘bureaucratic nightmare’.28 Nevertheless, the Bill passed on 8 October 1975. It provided the regulatory framework for commercial activity in the following years and sustained only a few amendments, most notably those in 1976 and 1983.

What really undermined Labour’s efforts at price control was the fact that government spending continued at a high level. The financial situation in 1973 allowed for such expenditure but when ongoing costs had to be factored into the budget of 30 May 1974, the climate was much less congenial. After a long summer drought and sliding export prices, especially for meat, revenue projections looked much less rosy. Rowling found himself saddled with a ballooning liability for subsidies which were being pumped up by inflation. And there were costs associated with the newly established government-owned New Zealand Shipping Corporation that Kirk had been urging since the mid-1960s in the hope that it would revitalise coastal shipping. After several delays, Cabinet finally approved the project on 2 July 1973. The Shipping Corporation proved to be a white elephant, losing nearly $5 million in the year to 31 August 1979 and more than $7 million the following year.29 There were costs, too, with the New Zealand Export-Import Corporation, which was a new government body aimed at boosting the country’s trade. It was the same with the newly created Rural Banking and Finance Corporation that was separated out from the old State Advances Corporation, now named the Housing Corporation. Increased benefit payments, new training, export and production incentives, and further money for regional development, culture and recreation, housing, education and health pushed expenditure up by 19 per cent for 1974-75. A huge extra weight was being added to the ship of state at a time when the economic tide was ebbing rapidly. Optimistic growth strategies and expensive social programmes meant that Labour was using up its good will at an alarming rate. The bumper year of 1972-73 was now a distant memory.

The Accident Compensation Commission, which opened its doors on 1 April 1974, was one of the new, and ultimately costly, schemes. It had its genesis in Justice Woodhouse’s 1967 Royal Commission report on compensation for personal injury. Further studies resulted in ‘landmark’ legislation by Marshall’s Government.30 Previous employers’ liability arrangements dated back to British law in the 1840s which had been brought up to date in the New Zealand Employers’ Liability Act 1882 and refined in a number of Workers’ Compensation Acts between 1908 and 1956. Woodhouse expressed the opinion that ‘just as modern society benefits from the productive work of its citizens, so should society accept responsibility for those willing to work but prevented from doing so by physical incapacity’.31 The new scheme was funded by levies on employers, the self-employed and motorists and paid according to a ‘no fault’ principle. It paid full medical costs and 80 per cent of an accident victim’s lost earning capacity up to a set sum, until the age of 65. There were several lump sum benefits as well. Kirk’s Government added to the cost of the scheme by extending coverage to non-earning victims of accidents, with the extra burden carried by the Consolidated Fund.32

The Commission became a Corporation in 1981. Neither was free from controversy. Problems of defining accidents, the scope of medical reimbursements and constant claims of malingering clouded Woodhouse’s vision of a fairer society. The very existence of such a comprehensive system for accident victims threw into stark relief the less generous benefits available to victims of illness or physical deterioration. An industry developed where large numbers of patients with the connivance of their doctors chose to define illnesses as accidents, thus pushing up ACC costs and the money required to fund the system. For some employers, ACC levies became substantial burdens, while many ordinary people who were ill were left grumbling about the inequities of life. Seated in the middle of a haphazardly constructed welfare state, ACC had its benefits trimmed by successive governments that lacked both the money and the willingness to eliminate anomalies or to pay for the abuses to which ACC was being subjected. While a great many people have benefited from its services, ACC has been costly both for taxpayers and employers. Consumers have carried the costs of ACC in the prices they pay for goods and services and the imposition has been greatest on those with the lowest incomes.

The Third Labour Government also inherited the Royal Commission on Social Security which had been set up under Justice Thaddeus McCarthy in September 1969 in response to a request from the National Development Conference for an ‘independent and penetrating examination’ of social security. Like McCarthy’s other inquiries, his report on Social Security in March 1972 gave a full summary of developments to date, questioned few fundamentals, made recommendations that carried a huge price tag and could scarcely be described as a ‘penetrating’ inquiry. ‘We have not been persuaded that our social security system should be radically changed at this time’, said the report.33 Some increases, such as a doubling of the Family Benefit to $3 per child, per week, had been incorporated into Muldoon’s 1972 budget, while the General Medical Services Benefit, which increased in 1969 for some categories of patients, was further increased for all categories in 1972 and then again in December 1974. Other recommendations of the McCarthy Royal Commission such as the Domestic Purposes Benefit were left to Labour to implement. Meantime, rapid inflation was calling into question the adequacy of some of the increases made as recently as 1972. The Government’s commitment to welfare was rising steeply at a time when New Zealand’s economic capacity to carry extra burdens was being seriously challenged. The warnings of the Gibbs taxation committee of 1951 look prophetic in retrospect.

There was a prescient quality to Norman Kirk’s illness which followed an operation for varicose veins on 10 April 1974. The ups and downs in his health over the next few months both reflected and affected the declining state of the economy and sagging public confidence in his government. Kirk’s death in the Wellington Home of Compassion on 31 August removed from New Zealand life at one blow Labour’s last credible enthusiast for big government. In retrospect it seems that the tears in the days that followed were for more than the passing of an unusually talented man. An era was ebbing away.34

There was a flicker of hope that Rowling, who took over as Prime Minister on 6 September 1974, might be able to rescue both the economy and the Labour Government. The new Prime Minister differed fundamentally in style from his predecessor. ‘I wouldn’t pretend for a moment to be a Norman Kirk’ were his first words as Prime Minister. Smaller and softly spoken, he liked the description - ‘a decent sort of chap’ - that the media bestowed upon him. ‘Throw me into a crowd and I’d disappear…. I’m not an effervescent person, I’m not belligerent, I’m not a great orator. I like reasoned and quiet judgements, and I suppose I’m not spectacular’, he told a journalist early in 1975.35 Some Labour MPs began talking privately a few weeks after Kirk’s death about holding an early election, in order to seek a fresh start. Rowling demurred. Time, however, was not on Labour’s side. The collapse in economic growth around the world that caused commodity prices to sag in 1974, coupled with rising oil prices, gave no ground for optimism. Once more it looked as though Labour’s leaders were being forced to switch from playing Santa Claus to Scrooge. Meantime, the unceremonious dumping of Jack Marshall from the leadership of the National Party by Robert Muldoon in July 1974 gave inspiration to the Opposition and heightened tensions within Parliament.36

By the end of 1974 public opinion polls were running against the Rowling Government. Bob Tizard, the new Minister of Finance, was every bit as much a Keynesian as Kirk and Rowling. But he was forced to concede that while full employment remained Labour’s top priority, the deteriorating balance of payments would reduce growth rates and make new spending difficult. On 24 September 1974 Tizard devalued the New Zealand dollar by 6.2 per cent. He told a meeting on Auckland’s North Shore a few weeks later that the Government hoped to ‘ward off recession and unemployment’.37 But the turnaround in New Zealand’s current account had swung from a surplus of $250 million to a deficit approaching $600 million. He expected real growth to be less than 1 per cent in the year to June 1975.38 Even this dismal assessment of the severity of the economic turnaround was too sanguine; in April 1975 Tizard conceded that the prospects of a quick recovery in the world economy looked even bleaker.39 In the year to June 1975 there was a balance of payments deficit of $1.43 billion.40 The Government had borrowed nearly $1 billion abroad by the middle of 1975.

Tizard’s problem was that Labour’s increased spending had been predicated on a better revenue flow and lower inflation. By budget day on 22 May 1975 subsidies alone were costing $162 million and topped $182 million in the year to March 1976. They had been the subject of intense debate within Cabinet and the Labour caucus. Against the better judgement of many senior ministers, MPs decided that the 1972 promise to stabilise those costs over which Government exercised control should be honoured. However, with milk held at 4 cents a pint in the belief that it would help low income families, farmers were now receiving the equivalent of 6.36 cents per pint when they sold their milk. Those who bought milk back at the subsidised rate to feed to pigs, calves and lambs were able to enjoy a considerable financial advantage. The milk subsidy had become one of the dearest and least effectively targeted forms of family assistance in the chequered history of the welfare state.41

The Government’s willingness to let public service numbers rise, as a means of mopping up growing unemployment, helped drive Tizard’s budgeted increase in expenditure to 28 per cent. This came on top of Rowling’s 26 per cent actual increase the previous year.42 Yet the Labour Government felt there was still room for new spending. A standard tertiary bursary and additional house lending found their way into the 1975 budget. On top of a general wage increase that was included in the budget, these threatened to strain it severely. In a complex juggling act Tizard reduced tax rates for many on lower incomes, while returning the top marginal rate to 60 per cent and boosting sales taxes on several consumer items. The price of petroleum products rose once more as vaulting world prices bore in upon a small economy which, like so many others, had geared itself to oil consumption.

Tizard estimated his budget deficit would be about $500 million. By December 1975 inflation had reached 15.7 per cent. Coupled with the effects of a further 15 per cent devaluation on 14 August 1975, the actual deficit for the year reached more than $1.1 billion.43 At the time of his budget, however, Tizard believed that the worst was over and that a policy which he admitted was one of ‘both risk and sacrifice in the pursuit of social and economic justice’ was a worthy goal.44 He was voicing the thoughts of his caucus and many within the wider public; there was nothing in New Zealand’s recent past to prepare them for another generation of low world commodity prices.

The economic turnaround between 1973 and 1975 was so sudden, and so drastic, that it provided an unparalleled opportunity for a political opportunist. Muldoon attracted a personal following which he called ‘Rob’s Mob’. It was a collection of the disaffected, numbering among them pensioners terrified by inflation and nostalgic for better times, anti-abortion crusaders caught up by a morals issue of the moment and many from the rural sector that was now suffering acutely from stagflation. The National Party’s election spending in 1975 was the largest in its history to date.45 The campaign was unparalleled for its ferocity; claims and counter claims, character assassinations and carefully planted insinuations wafted through the press and danced across television screens.46 Rowling’s Government paid a price for its profligacy and went down to heavy defeat on 29 November 1975. Muldoon’s mix of nostalgia, extravagance and belligerence comforted voters in their state of unease. Labour’s parliamentary majority of 23 turned into the same margin for National.

Rowling’s Cabinet had not been strong; nor was the new Muldoon Ministry which took office on 12 December 1975. While his deputy, Brian Talboys, J. B. (‘Peter’) Gordon, Duncan Mclntyre, George Gair, Les Gandar and Hugh Templeton all had experience, there was a long tail to it. When the new Prime Minister, like Sid Holland before him, appointed himself Minister of Finance, he became New Zealand’s economic supremo. As Templeton later revealed, standing up to Muldoon in Cabinet was not easy during his eight and a half years at the helm. Derek Quigley, one who did, was summarily fired in 1982.47 Most senior ministers, including Muldoon’s deputies in the Finance portfolios, were often not shown key Treasury briefing papers. The Prime Minister’s Department, which had been planned during Rowling’s time, became a separate entity from Foreign Affairs. It was headed by a senior Treasury official, Bernard Galvin, between 1975 and 1980. The office grew in power. Little of significance was announced by any minister without its sanction.48

The stark reality, however, was that neither party in 1975 had any remedy for the economic setback which the Institute of Economic Research called ‘the deepest and most prolonged post-war recession amongst the industrial capitalist countries’.49 In Great Britain, the United States and Australia, similar policies of managing economic demand and selective stimulation were faltering. Yet no other policies looked palatable to the welfare generation. The basic problem was that big spending in a small economy like New Zealand’s at a time of rampant inflation only increased demand for scarce foreign exchange and necessitated further borrowing both overseas and domestically and/or further devaluation. Retrenchment, on the other hand, would rapidly increase unemployment, which was rising steadily in New Zealand in any event, reaching 14,000 by census day in April 1976.50 Muldoon ridiculed Labour’s policy cake as ‘borrow and hope’ but cooked from the same recipe book. The inherited political wisdom of 40 years still prevailed and as yet there were no signs of rethinking within either party’s caucus.

On the day he took office Muldoon released some briefings he had received on the state of the economy. They were gloomy. He told reporters that ‘a small cut in the standard of living is necessary, but it need not be very painful for the average citizen. There is not about to be a great depression, but a few things have to be tidied up.’51 These words summarised Muldoon’s overall approach to economic management. He would constantly use the words ‘fine tuning’. Despite his penchant for sweeping statements and a reputation for ruthlessness, he moved cautiously, adjusting this and tinkering with that in a manner that some businessmen found disconcerting. When it seemed not to be working he would divert public attention from his economic management. Nuclear ship visits, Pacific Island ‘overstayers’, a Maori land occupation at Bastion Point in Auckland and sporting contacts with South Africa leading up to a Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand in 1981 in the run-up to his third general election, provided continuing sideshows from which the Prime Minister was a master at extracting the maximum political capital.52

Prime Minister Robert Muldoon and B. V. Galvin, Permanent Head, Prime Minister’s Department, 1978. Evening Post

For the first two years Muldoon accepted some advice from his Treasury officers. Within ten days of taking office the new ministry pruned immigration numbers, cut many subsidies and allowed rail, electricity and postal charges to rise. The price of milk doubled to 8 cents, although a subsidy of 3 cents a pint remained. Bread rose 1 cent for a standard loaf on 12 January 1976. Applications for new house loans were temporarily suspended in order to take some heat out of the building sector.53 The Federation of Labour was told that the expected wage increase in January 1976 would be lower than expected. The press noted a mood of ‘dour realism’ settling over ministerial offices. Meetings of Cabinet and its committees often ran into the evening.54 The incoming ministry told officials that it wanted to see resources shift back to the private sector.

The Government targeted the public service for restraint, since more than 20 per cent of New Zealand’s total labour force was now directly on the State’s payroll, considerably above the historical average of the last decade of 18.8 per cent. What some called a public service culture in Wellington had reigned largely unchallenged for years. A journalist working in the city at the time recalls the scene:

anything approaching the definition of real work was regarded, particularly in government departments, as a form of perversion; turning up for an eight-hour day … was all that was required; the Dominion crossword would see an army of grey-cardiganed clerks through nicely until morning tea time, and the first edition of the Evening Post, to help while away the afternoon, was on the streets at 1 pm; the Public Service Association ruled the city….55

National ministers were not so daring as to challenge this head on but they did cap public service numbers. On 8 March 1976 Cabinet applied a staff ceiling to all departments except Education and Health. The universities were also exempted. Several major construction projects were also placed on hold. However, no guidelines were issued to explain the principles behind the restraints and a strong suspicion developed that decisions were being made on the basis of whether the outcomes were likely to injure the National Party’s electoral coalition. On 8 April 1976 the Cabinet Committee on Expenditure decided not to remove the remaining milk subsidy. Even in his bold first few months, caution was Muldoon’s watchword.56

Some of the Government’s supporters in the wider community thought a level of unemployment would provide ‘the necessary incentive for the average person to become more interested in his job’, but ministers were not prepared to go so far.57 While saluting the traditional goal of full employment,58 Muldoon’s Government did risk removing parts of the insulation in which the economy had been so tightly wrapped for many years. In a major statement on 2 March 1976 the Cabinet revoked the Interest on Deposit Regulations in the hope that flexible interest rates would enable trading banks to compete more easily for funds and play a bigger role in house lending. Controls on overdraft rates would also be removed.59

Yet, having removed one layer of protection, Muldoon became uneasy about shifting others. He seemed happier using import and price controls than any National predecessor and in March 1979 both he and Lance Adams-Schneider, his Minister of Trade and Industry, strongly defended import controls against their critics. Like Holland in 1951, Muldoon also argued for price controls, telling the Council of Building Industries in March 1976 that they were an essential accompaniment to wage restraint: ‘It would be inequitable to single out a particular industry or group for exemption from either set of controls’. Not all agreed. Professor Allan Catt of Waikato University supported him; but the New Zealand Financial Times called price controls ‘one of New Zealand’s more disastrous social and bureaucratic experiments’, arguing that they fostered inefficient industries by applying cost-plus and were really a political device for ‘redistributing income from the efficient firm to the consumer by way of manipulation of prices’.60

Evans summarises the mad rush on budget day in anticipation of higher prices, July 1976. NZ Herald

Muldoon was cautious with subsidies. Having railed against them in Opposition, he slashed them on taking office, then let them mount again until after the 1978 election by which time they were costing $120 million p.a. In 1979 Muldoon trimmed subsidies a little, only to see them rise to $158 million in 1980. As with Labour, price controls were part of his armoury to keep prices, and hence wages, in check at a time when the Government continued to spend freely. When people questioned their worth, Muldoon would agree with them. Subsidies, he told one correspondent, ‘conceal the real costs of items involved and can therefore result in a misallocation of resources within the economy. It is important that prices should reflect the real costs of production.’61 Having said this, Muldoon never found an appropriate time to get rid of them all.

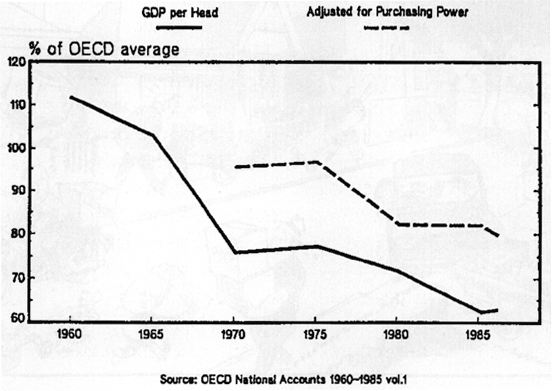

New Zealand’s Income Per Head Relative to the OECD Average

1960 – 1986

PRODUCTIVITY GROWTH

business sector: average % change at annual rates

These graphs and figures speak for themselves. From the New Zealand Planning Council report, The Economy in Transition to 1989, Wellington, 1989.

Not content with the existing battery of controls, Muldoon armed himself with new weapons. In the Economic Stabilisation (Cost of Living) Regulations 1980 the Arbitration Court was asked to take changes in the rates of personal taxation into its calculations before deciding on wage increases. In 1981 Treasury officials were also put to work on a complex investigation into taxation and the extent to which any cuts could be factored into the CPI. Officials advised against tampering with the basic structure of the index. Muldoon eventually desisted.62

Like Kirk, Muldoon admired what he labelled New Zealand’s ‘egalitarian tradition’. He declared he would use his powers to ensure ‘equal opportunity for all New Zealanders’. He intended to see that the burden of adjusting to a lower standard of living would be shared equitably, ‘with those on the lowest incomes suffering the least hardship’.63 Muldoon claimed that his various controls were to help ‘the ordinary bloke’. His solicitude never sat easily with the National Party establishment. As debate grew in financial and business circles, with more and more people questioning whether his controls could work or whether they simply retarded growth and efficiency, unease turned to criticism. Some younger National MPs were questioning whether the public any longer received value for money from increased government expenditure.64 There were still a few, however, who seemed enthusiastic about government intervention in the economy and liked plans, rules and regulations as much as the Labour MPs they had defeated in 1975.65

Eventually Muldoon tired of Treasury criticisms of controls and regulations. Such advice conflicted with his own inclination to manage the economy. Above all he admired Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore, who presided over a highly centralised State. When the cutbacks of 1976 overshot the mark, exacerbated the recession in 1977 and produced a fall in the growth rate of -1.8 per cent for the year, the Prime Minister decided to become more interventionist.66 His budgets reverted to the pattern of a decade earlier and were peppered with livestock incentive suspensory loans, new fertiliser subsidies, noxious plant control subsidies, livestock TB detection programmes, lucerne establishment grants, tax rebates on pesticides used by pipfruit growers, investment incentives for industrial machinery, regional investment allowances, new export incentives, government guarantees for loans raised for new tourist accommodation, forestry encouragement loans, fishing industry subsidies and rebates, grants to encourage the use of natural gas and a great many other forms of targeted assistance.67 Like the Third Labour Government that he regularly criticised, the Third National Government was equally convinced that New Zealand’s growth rate could be stimulated by selective interventions. In April 1976, at the urging of Talboys, who was Minister of National Development, the old planning structure was rejigged. Sir Frank Holmes was appointed to head a task force on the future of economic and social planning. A Planning Council and a Commission for the Future, which had been promised in National’s manifesto, were subsequently established. Treasury officials were sceptical about the usefulness of these bodies but ministers were hoping to widen their sources of advice. However, they liked little of what they received from the Planning Council.68

There is little evidence that Muldoon’s interventionism had beneficial results in counteracting adverse movements in overseas prices. Export receipts gave only a flicker of recovery in 1977 and declined later in the year. In his budget on 21 July 1977 Muldoon estimated that New Zealand’s terms of trade had slipped by between 35 per cent and 40 per cent since 1973. Inflation, which reached nearly 18 per cent in the middle of 1976, fell back to 12 per cent a year later. It then rose again, pushed along by a steady increase in government spending, which rose 10.2 per cent in real terms between 1975 and 1978.69 Industrial unrest became more intense. There were several threats of union deregistration and lengthy troubles at Ocean Beach freezing works in Southland. Muldoon experimented for some months with a price freeze. Some idealists hoped that worker participation in management might improve employee morale. Early in 1978 Deputy Prime Minister Brian Talboys made an impassioned plea for workers and employers to change their attitudes to work, and to accept that more effort was required.70 Words had little effect.

Studies of individual industries that had begun with ceramics in 1975 continued. The Government sought to align those who were prepared to cooperate with the Department of Trade and Industry’s advisors to the modern trading environment. According to Muldoon, the goal was to encourage resources ‘to move into industries which are, or have a good prospect of becoming, internationally competitive’.71 Like a generation of ministers before him, Muldoon hoped to pick winners. However, none of his panaceas could be more than a Bandaid to an economy in such deep trouble. While weekly earnings rose nearly 16 per cent in the year to October 1978, the total number of private sector jobs contracted. Public sector job creation programmes tried to take up the slack. But there was a net outflow of people from the country of more than 63,000, many of them skilled people, between 1976 and 1979.

In spite of Muldoon’s efforts, unemployment continued to increase. It reached 50,000 in August 1978.72 There was renewed talk of the need for an ‘active labour market’ where the Government accepted responsibility for retraining and transferring workers from an area of redundancies to another with growth prospects. By now economic growth was virtually static and budget deficits increased each year. As an economic stimulant, Keynesian tax and spend was dead but neither political party seemed willing to acknowledge it. In a depressing prediction in August 1977, the OECD warned that on a moderate growth prediction New Zealand was likely to be obliged to borrow $9.5 billion before 1985 if it was to keep travelling the same course.73

After attacking Labour’s ‘borrow and hope’, Muldoon followed the same policy. Auckland Star

While the National Government had pruned expenditure in 1976, the introduction of National Superannuation added a huge extra burden to the Consolidated Fund. Labour’s New Zealand Superannuation, which had begun on 1 April 1975, was a contributory scheme. By the time of the election $79 million had been invested in it. Without changing the law, Muldoon informed employers on 15 December 1975 that they could cease collecting the levies for Labour’s funded scheme; their actions would be validated legislatively at a later date.74 The Prime Minister now introduced an unfunded system called National Superannuation to be paid for from existing taxation. From 9 February 1977 the new scheme paid 70 per cent of the average ordinary-time weekly wage for a married couple over 60 years of age, rising to 80 per cent from 30 August 1978. The single rate was 60 per cent of the married rate. Payments were adjusted every six months in line with surveys carried out by the Department of Labour. The payments were subject to a ten-year residence test. There was no means test unless a spouse for whom the benefit was claimed was under 60. However, ‘National Super’ payments were taxable.

Undoubtedly the most generous benefit ever to have been introduced in New Zealand’s history, National Superannuation quickly doubled in dollar terms the annual cost of the former old-age pension and superannuation combined.75 Muldoon insisted that no increase in taxation would be necessary, an assurance that led some to label it ‘Piggy Super’. But such assurances were posited on the assumption that economic growth would move along at an average rate of 3 per cent per annum, which showed no signs of becoming a reality. As a result, ‘National Super’ contributed to the ballooning deficit which Muldoon financed by borrowing, thus saddling future generations with the responsibility of paying a generous pension to the current legions of elderly.76 During the twenty years the scheme has been in operation it has remained the most costly, and hence the most controversial, welfare benefit. Less expensive, but steadily increasing in cost, was Labour’s Domestic Purposes Benefit. It was claimed by 17,231 people in 1975, by nearly 50,000 in 1983, and by 108,709 people in 1996.77 With more than 50,000 unemployment benefits being paid by 1983,78 the escalating expenses attached to New Zealand’s welfare system were precisely what the 1951 Gibbs Committee had warned against.79

Governments which hold out false hopes quickly lose popularity. Muldoon only narrowly held on to power at the election on 25 November 1978. The National Party received fewer votes across the country than Labour but managed to keep a parliamentary majority. As the economy fluctuated in 1977-78 and inflation rose again, it became cystal clear that Muldoon had no magic wand. In 1979 he faced another crisis, this one partly of his own making. Having allowed government expenditure to rise by nearly 21 per cent in election year, he was now staring at a deficit of more than $2.3 billion unless there were economies. ‘Our plight’, wrote the editor of the New Zealand Herald early in January 1979, ‘is one of sustained excessive pressures on overseas funds, internal inflation which remains too high, a huge budget deficit, and unemployment which would be worse if tens of thousands had not fled to greener fields…. Some sort of correction seems virtually inevitable before much longer.’80

As Muldoon floundered, advice poured in from many quarters. Several Auckland business leaders made a plea for more flexibility; the taxation specialist, L. N. Ross, declared that New Zealand had become ‘a soft and flabby society, lulled into a false sense of wellbeing by a social welfare system that yet may prove too costly to maintain’. He added that in his opinion people had become too dependent on the Government and on bureaucratic direction and protection ‘to the detriment of personal initiative, enterprise and work’.81 The Auckland Harbour Board blamed its lack of profitability on overmanning, high waterfront levies and the central wage-fixing policies of the Waterfront Industry Commission. Some farming leaders talked of the need for restructuring to encourage ‘efficient export industries’, something that Ian McLean, one of Muldoon’s new MPs, supported in a well-written booklet that he had produced for the Planning Council.82 The Chairman of Progressive Enterprises Ltd, Brian Picot, sought a change in New Zealanders’ attitudes and thought the Government needed to become the principal educator. Len Bayliss, chief economist at the Bank of New Zealand, who had previously served in the Prime Minister’s Department, argued for an end to Muldoon’s ‘usual array of ad hoc policies’. Bayliss argued that subsidies, incentives, new committees and advisory boards were no more than short-term reactions to pressure group demands.83

Interest groups that had welcomed big government more than a generation before were losing their faith. The Grocery Manufacturers Association had gone along with price controls in earlier years. At its annual conference in October 1978 the association discussed a world without controls and regulations and grilled Harry Clark, Secretary of Trade and Industry, when he addressed members. Clark found the Auckland Manufacturers decidedly apprehensive when he met them early in April 1979. On the one hand they accepted that there needed to be some restructuring; on the other hand they could not work out how to jettison the whole protective apparatus. Clark later told Talboys that manufacturers seemed constantly to be looking for ‘scapegoats’ which they believed were contributing to their sector’s poor export performance.84 Meantime the New Zealand Chambers of Commerce, which had never been enthusiastic about big government, although they had, for a time, held high hopes of centralised planning, published and circulated a paper by Sven Rydenfelt of Sweden. It pointed out that the Swedish economy and welfare system, which New Zealand advocates of big government often quoted as models for reform, were nearing collapse.85 Interest groups seemed ready to change, but in what direction?

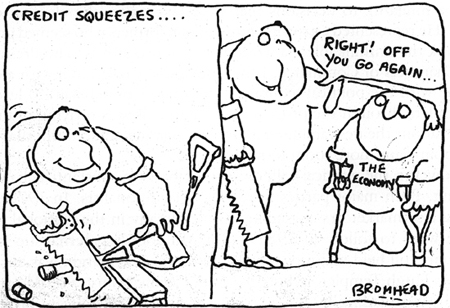

Cartoonist Bromhead comments on Muldoon’s credit squeezes, 1979. Auckland Star

Dr Donald Brash had some ideas. He was general manager of Broadbank Corporation and convenor of the Planning Council’s Economic Monitoring Group that had taken over from the Monetary and Economic Council. He told an audience in February 1979 that he hoped the Prime Minister would grasp the challenge of the hour and tell the nation the cause of its difficulties. He described these as ‘a combination of external factors and policies followed by governments of both political parties over many years’. What was needed, he said, was ‘a package of measures’ to rectify the situation. He suggested devaluation accompanied by the phasing out of all export incentives. Import controls as a major means of protecting New Zealand’s industry should be abolished, along with price controls and barriers to foreign investment. Brash suggested a progressive switch to indirect taxation and a ‘vigorous attempt’ to cut government spending, including some trimming of National Superannuation.

Brash’s advice angered some, was debated by others and ultimately bore a similarity to decisions that were taken after the election of July 1984. He represented a growing number of reformers who seemed prepared to think the unthinkable – a world with fewer controls. The President of the Chambers of Commerce, J. R. Greenfield, backed him with a call for people with the political ‘courage, determination and skill’ to lead New Zealanders through the process of change. Talk was reviving in business circles about the desirability of a four-year parliamentary term that would give politicians more room to manoeuvre.86

However, the political willpower to embark on substantial change was missing. Both major parties were led by traditionalists. In 1978 several young free-marketeers augmented those already in the National caucus. More were to follow in 1981.87 But Muldoon’s paternalistic style of economy still held majority support, although the margin was becoming fine. As Hugh Templeton describes it, the Prime Minister’s ‘old comrades in arms were fading by his side’. In October 1980 a group of younger National MPs tried to topple Muldoon from the prime-ministership after he failed to give whole-hearted support to Brash, who was National’s candidate in the East Coast Bays by-election in September 1980. A determined Muldoon soon humbled the ‘colonels’, as they were labelled. His eventual success was more a tribute to his guile than to any strong belief in his policies.88

Leader of the Opposition, W. E. Rowling, visiting New Zealand Steel’s construction site, 1977. NZH

Neither was the Labour caucus happy with its economic direction. The late 1970s was a defining era for left wing parties in many countries, especially in Australia and New Zealand, where they were out of power and regrouping their forces.89 Rowling straddled the New Zealand Labour caucus uneasily between 1975 and 1978. A team of new, younger MPs elected in 1978 supported him for a time,90 but their opinions became more diverse. Some were uneasy about increasing centralisation and endless economic tinkering. Others were social engineers and keen to involve central government in a variety of causes, especially those relating to women’s affairs. The strength of this latter group was augmented in 1981 and they were to argue vociferously for equal pay, access to abortion, advancement for nurses, midwives, social workers and teachers, the use of schools for peace studies and a downgrading of those things believed to advantage boys. These issues, involving as they did a high degree of central direction, interested them more than the state of the economy. A division was opening within the Labour caucus between those who wanted to promote state intervention on the grounds that they knew best and those who felt that big government had passed its ‘sell-by date’ and that it was imperative to get the economy right before there would be any new money to spend on social agendas.

Among the latter group, Rowling set teeth on edge when he dismissed Brash’s arguments for freeing up the economy in February 1979. ‘The experts should stop making sweeping statements about the need for change and sacrifice. This only scares people and makes them reject the advice,’ he told a leadership course at Lincoln College. Rowling’s homily sounded rather like Muldoon’s instruction to his officials not to bring him advice that might threaten his Government’s hold on office.91 Rowling’s solution to New Zealand’s problems was more manpower planning which accepted full employment as a goal and an active state sector in housing and community care. New Zealanders should acknowledge that ‘the quality of life is not measured in terms of dollars and efficiency alone,’ he added.92 To those in the Labour caucus who shared the party’s traditional ambition to assist people, but who wanted new ways of doing it, Rowling and his senior spokespeople seemed to be stuck in a well-worn groove that was taking neither the country, nor the party, anywhere.

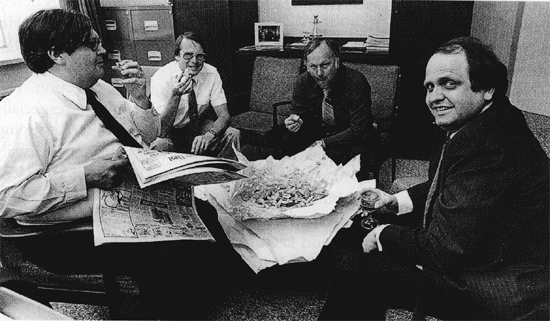

The ‘Fish and Chips Brigade’ after trying to topple Rowling from the leadership of the Labour Party, 12 December 1980: from left, David Lange, Michael Bassett, Roger Douglas, Mike Moore. NZH

On 1 November 1979 Bob Tizard was replaced as Deputy Leader of the Labour Party by David Lange.93 However, Tizard’s continuing influence over economic policy led the MP for Manurewa, Roger Douglas, who was the only one of the younger Labour MPs with ministerial experience, to produce an ‘alternative budget’ to Muldoon’s in 1980. He followed it up in November with a booklet There’s Got to be a Better Way! A Practical ABC to Solving New Zealand’s Major Problems.94 For some years now Douglas had been an advocate for tax reform and had successfully made it Labour’s issue at the 1978 election. He was involved in the business world, having taken over his family’s drug company, and was in the process of turning it into a significant exporter to Australia. Douglas thought Labour’s official commitment to further tinkering with a high spending economy was an expensive waste of time. He argued for a fundamental rethink. In the middle of 1980 he resigned as Labour’s spokesman for Trade and Industry so as to preserve his freedom to produce further policy initiatives. As he roamed the caucus propounding new ideas, the numbers of disaffected Labour MPs grew. In December 1980 pressure was applied to Rowling to step aside. But he retained his leadership in a caucus confidence motion by one vote – his own.95 Since it was now clear that central direction of New Zealand’s economy was not producing the intended results, its defenders were everywhere under attack. However, the old world, like King Charles II, was an unconscionable time a-dying.