Two

BUILDING A CITY OF

OUR OWN

In 1920, prosperity once again came to North Park. A population explosion in 1921 and a severe housing shortage led to the construction boom of 1922 to 1925. To support the increase in population and construction, water, electricity, gas, and streetcar infrastructure were all upgraded. While land along the streetcar lines continued to attract development, ever-rising land costs and the increasing popularity of the automobile convinced investors to redirect their efforts to developing El Cajon Boulevard and new housing tracts in southeastern North Park. Gas stations, restaurants, automobile sales and repairs, and other retail establishments catering to the automobile began to appear on El Cajon Boulevard in the late 1920s. In the meantime, University Avenue became an entertainment, dining, and shopping destination. In 1926, the lighting of University Avenue, North Park’s “Great White Way,” was celebrated with floats, dancing, and music, with 10,000 people in attendance. In 1928, Emil Klicka, who developed the North Park Theatre, declared, “As to North Park, I believe that within a few years we are going to have a city of our own in this district.” Indeed, several thousand residents of the North Park district petitioned the city council for a branch city hall in 1930. With the stock market crash and the onset of the Great Depression, however, that request was denied. Construction slowed and became lackluster until 1935, when the federal government introduced programs for home ownership. Even with the real estate and construction turnaround that year, business remained sluggish until the Great Depression officially ended in 1939. North Park’s commercial core thrived once again as retailers catered to locals living in the earlier-developed housing tracts. With the Depression over and San Diego gearing up for the coming war, the population exploded. Between 1941 and 1945, San Diego’s population more than doubled to 500,000 inhabitants. Another boom in development commenced. San Diego would never again be the sleepy town it was prior to World War II.

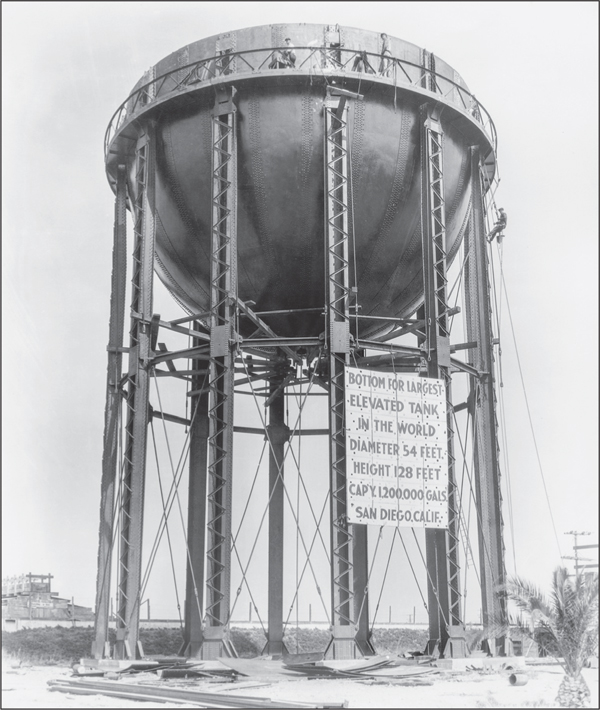

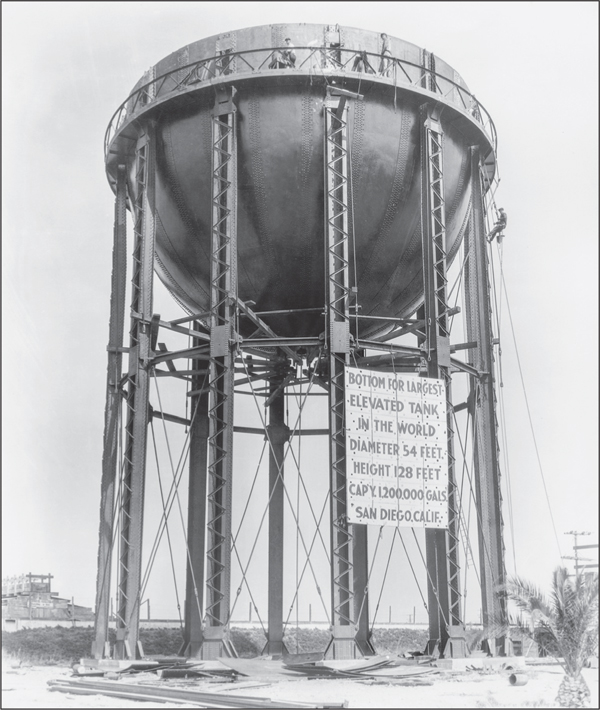

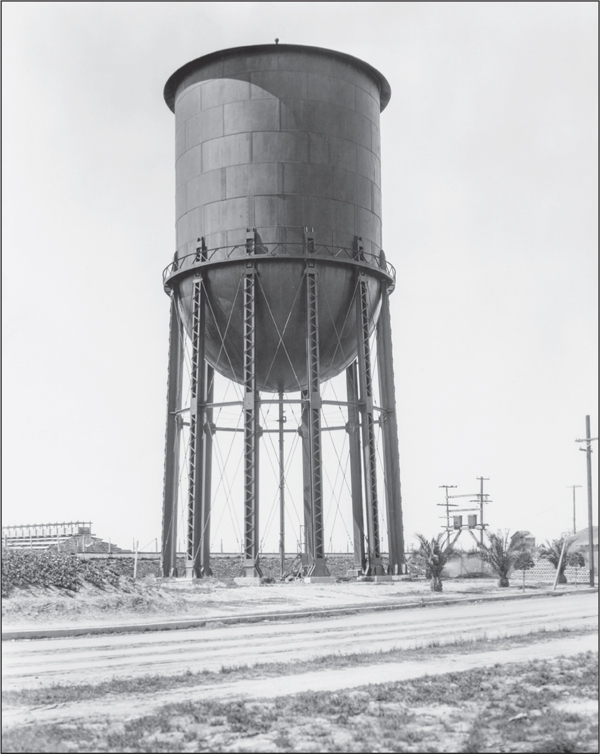

THE WORLD’S LARGEST ELEVATED TANK, 1924. Water pressure became a problem in the 1920s because of the rapidly growing population on the mesa north of Balboa Park. In 1923, a municipal bond election funded a new water tank to hold 1.2 million gallons. As indicated by the sign, the tank was believed to be the largest elevated tank in the world. Water treatment facilities can be seen to the left.

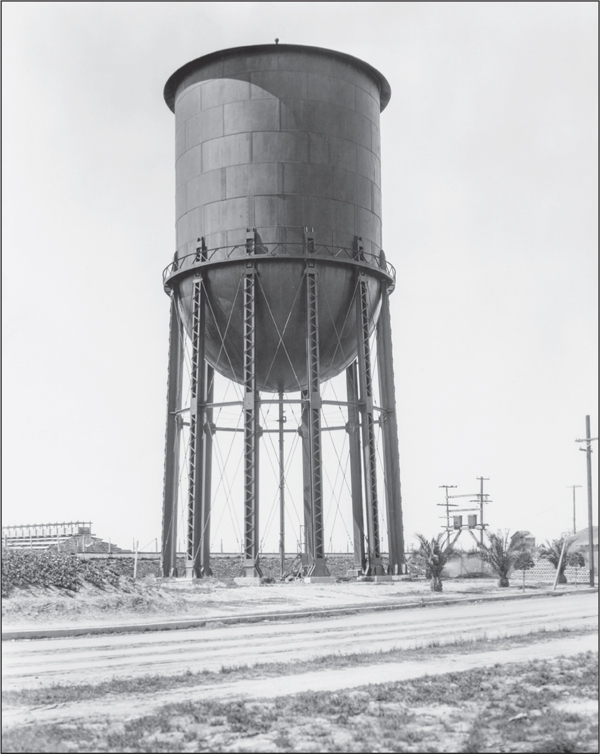

NORTH PARK’S WATER TOWER, 1925. Just south of El Cajon Boulevard between Oregon and Idaho Streets, the water tower remains one of San Diego’s most visible and recognizable landmarks, as well as a symbol of the North Park area. The Pittsburgh–Des Moines Steel Company built the tower. The structure and the surrounding area were listed in the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district in 2013.

ELECTRIC SUBSTATION F, 1926. On April 15, 1926, a building permit was issued to the San Diego Consolidated Gas and Electric Company (now SDG&E) for a tile and stucco substation at 3169 El Cajon Boulevard between Iowa and Boundary Streets. Construction cost was estimated at $38,000. In those days, the northeast section of the city, including North Park, placed a great demand on the company. Therefore, plans were made in 1925 to build a substation to serve these growing neighborhoods. The formally balanced two-story building was modeled in the style of a Spanish Renaissance villa to blend in with the neighborhood. Busts of Thomas Edison and Benjamin Franklin were chosen by the local residents to adorn the facade. (Above, courtesy of the Covington family; below, courtesy of the San Diego History Center.)

GEORGIA STREET BRIDGE, 1929. When University Avenue needed to be widened to accommodate double tracks for the No. 7 streetcar line in 1914, city engineer J.R. Comly chose the aesthetics of the City Beautiful movement for the concrete-arch replacement bridge and supporting vertical walls. The bridge celebrated its 100th birthday in 2014.

THIRTIETH STREET BRIDGE SKETCH, 1931. The Thirtieth Street Bridge over Switzer Canyon was a challenge to maintain. Its wood decking had been replaced repeatedly due to heavy traffic and deck fires from matches and cigarettes dropped from automobiles and streetcars. J.R. Comly proposed this elaborate concrete-arch replacement bridge in 1931. The $275,000 estimated cost once again led the city to appropriate $1,000 to repair the existing bridge.

PCC STREETCAR, 1940S. Presidents Conference Council (PCC) Streetcar 525 on the No. 2 line travels southward on the Thirtieth Street Bridge over Switzer Canyon. These single-end streamlined streetcars were introduced in 1936–1937. The modern streetcar, the result of a committee formed in 1929, was designed to be quieter and more comfortable. (Courtesy of San Diego Electric Railway Association.)

STREETCAR ON ADAMS AVENUE, 1949. In 1923–1924, fifty Class 5 streetcars, numbered 400 through 449, were purchased for John D. Spreckels’s San Diego Electric Railway system. Streetcar 417 on the No. 11 line travels eastward from the brick carbarn located at Adams Avenue and Florida Street. Completed in 1913, the barn was demolished in 1979, and the area became Trolley Barn Park in 1991. (Courtesy of Larry Hall.)

SAN DIEGO FIRE STATION 14, 1925. This Spanish Revival–style building was constructed on the south side of University Avenue between Grim Avenue and Ray Street on land donated by Mary Jane Hartley. Its landmark lofty tower was functional as well as decorative, providing an ideal place for drying the heavy fabric fire hoses after use. The fire company was relocated to Thirty-second Street at Lincoln Avenue in the 1940s.

THE “TENT” BUILDING, 1928. As seen from the north side of University Avenue at Grim Avenue, the Nordberg, or “Tent,” building occupied the intersection’s southwest corner. During the 1920s, the Tent was a neighborhood dance hall located above a commercial storefront. The recently renovated building was once home to Thrifty Drug Store and most recently has served as a fitness center. The fire station tower can be seen on the left.

HARTLEY ROW, 1923. Located on the south side of University Avenue at the southwest corner of Ray Street, this commercial building once housed the Merritt Baking Company, whose row of up-to-date delivery vans line the street in this photograph. The Schloss family’s A and B Sporting Goods has occupied the building’s corner position for decades, and tenants to the west have included restaurants, jewelers, shoe stores, and clothiers.

UNIVERSITY AVENUE, 1922. The handsome white brick and tile Granada Building, as seen in the distance on the southeast corner of University and Granada Avenues, has remained one of North Park’s least-changed commercial buildings during its nine decades. The Spanish Colonial and Pueblo-style buildings in the foreground were completely remodeled long ago to a nondescript uniform facade.

KLICKA LUMBERYARD, 1926. Emil and George Klicka were brothers whose family owned a wood-products company in Chicago. They moved to San Diego in 1921 and settled in North Park. In 1922, they opened a large lumberyard in the 3900 block of Thirtieth Street. The Klicka Lumber Company and the Dixie Lumber Company (forerunner of Dixieline) on Ohio Street supplied much of the lumber for the new streetcar suburbs. The Klickas’ business interests included the building of the North Park Theatre and publishing of the first North Park News. George Klicka developed a kit home in the 1930s, and more than 2,000 were sold throughout San Diego. The Klicka lumberyard closed in the late 1940s and was the site of a Mayfair Market. The site is now the location of La Boheme condominiums. (Courtesy of the Covington family.)

NORTH PARK THEATRE, 1930 AND 1932. The North Park Theatre and Klicka Building opened as the jewel of the community’s commercial center in 1929. Originally part of the chain of Fox West Coast theaters, it was the first theater in San Diego built to show the latest craze, “talking pictures.” The theater, also built for vaudeville performances, has a proscenium arch stage and full-sized orchestra pit. Funded by Emil Klicka at an expected cost of $350,000, the building’s design featured a Spanish Renaissance facade with prominent arabesque friezes. The building also housed the Bank of America, shops, and medical offices. It hosted food drives for the community during the Depression (below). The bank remained in the building until 1950. After the theater closed in 1975, the building operated as a church and was then vacant for years before being restored in 2005. (Both, courtesy of B’hend and Kaufmann Archives.)

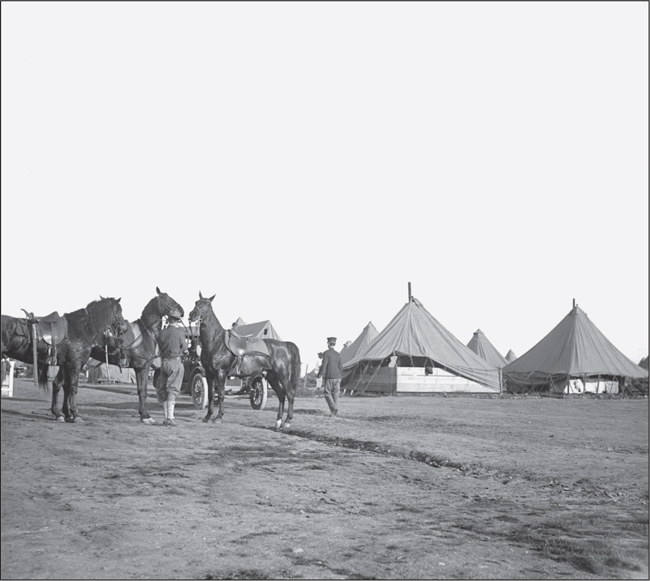

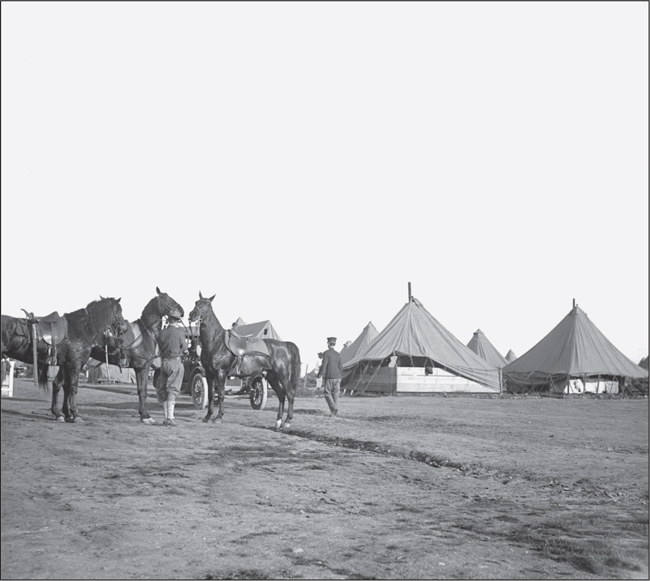

CAVALRY ENCAMPMENT AT MORLEY FIELD, 1915. In order to alleviate any concerns related to the 1914 Mexican Revolution, military units were stationed on the grounds of the 1915–1916 Panama California Exposition. A US Army cavalry unit was stationed at Morley Field. The cavalry also took part in parades and ceremonies. The camp was later removed, and John Nolen created the first city plan for the Morley Field area in the 1920s.

MORLEY FIELD AERIAL VIEW, MID-1930S. This photograph of Morley Field was taken after the 1935–1936 exposition. In addition to the 10 original tennis courts, the municipal swimming pool and clubhouse, baseball and softball fields, and the original dirt velodrome (bicycle track) are also visible. The Arizona Street Canyon is in the center of the photograph, which shows the topography prior to the landfill that began operating in 1952.

ORIGINAL NORTH PARK SIGN, 1935. The Ford motorcade enters the intersection of Thirtieth Street and University Avenue on its way westward to the grounds of the California Pacific International Exposition in Balboa Park, passing the Owl Drug Company building and Ramona Theatre on July 6, 1935. A special city ordinance allowed the North Park sign to be hung above the intersection. The sign had been installed that very morning.

EMMONS FAMILY HARDWARE STORE, 1927. This single-story brick commercial building is pictured at the northwest corner of Thirtieth and Upas Streets. In addition to the hardware store of Arthur and Rolene Emmons, the building’s tenants then included a grocery and a drug store. Though substantially remodeled, the building remains. The corner portion has served as a neighborhood bar for many years, most recently as the Bluefoot. (Courtesy of Charlene Craig.)

KEITH’S CHICKEN IN THE ROUGH, 1939. In the 1930s, several restaurants opened along El Cajon Boulevard in a new format—the drive-in, where waitresses would bring food to patron’s cars. Keith’s at Thirty-second Street was the longest running drive-in until demolished for the Interstate 805 freeway in the 1970s. The neon sign had a chicken dressed in golf clothes holding a club, with a golf ball behind him in the grass.

SERVICE CENTER, 1934. The service center in the middle of the pump island is visible in this close-up of the Standard (now Chevron) gas station at the corner of Park Boulevard and Normal Street. As with many other gas stations, the concept of service has changed along with the architecture. (Courtesy of Denis Pollak.)

SILVER GATE MASONIC TEMPLE AND GROUNDBREAKING, 1931. In 1930, the Quayle brothers, who had previously designed the North Park Theatre, were hired to design a major Masonic temple for the Silver Gate Masonic Lodge at the corner of Wightman and Utah Streets in the commercial district. Edward Fletcher, of the prominent Fletcher family, directed the campaign to raise $75,000. The photograph below shows the Masons at the groundbreaking ceremony in April 1931. The Masons are wearing the traditional Masonic apron, a symbol of honor. Fletcher is the tall person in the center of the second row. The building was completed on December 2, 1931. The Quayle brothers designed the temple to be a blend of a Mesopotamian ziggurat and an Egyptian temple, which were features found in the popular Art Deco style of the 1920s to the 1940s.