Former Victoria Police Homicide Squad detective Andrea Turner is not a religious woman. Doesn’t believe in angels. Or spirits or the supernatural. But strange events that occurred at a house on Phillip Island in which a young woman was strangled and painstakingly dismembered still send a shiver down her spine. Turner, an experienced Victorian cold-case murder and homicide investigator, was no stranger to kill scenes by 2009: whether they were bathed in gore or had been cleaned to some extent by killers. But ‘the creepy, creepy little house’, as she calls it, where innocent victim Raechel Betts met her awful demise will be etched in Turner’s mind forever.

Turner was part of Homicide’s Crew Two investigating the Betts disappearance-cum-murder. Fine work led investigators to the killer—a depraved Svengali-style drug dealer named John Leslie Coombes. He had murdered twice before. Turner remembers Coombes as simply ‘a creep’: a suspect who had a habit of flicking his tongue at a female detective. But Turner’s most vivid memories of that particular investigation centre on the slaughterhouse where Coombes sadistically reduced Raechel to garbage-bag fill. It was Melbourne Cup Eve— the night of the annual Homicide Squad social function in the city—when Turner was processing the house with a male crime scene examiner and a female crime scene trainee. Turner would have much preferred to have been at the squad party. The Phillip Island house belonged to one of Coombes’s playthings, a naïve interstater named Nicole Godfrey. Coombes had brought Raechel back to the house, strangled her in a bedroom and spent a night and a day cutting and pulling her body apart in a bathtub before disposing of it. Turner recalled Godfrey’s pet rabbit and Staffordshire terrier. During the crime scene examination, Turner said, the rabbit was ‘going crazy’ in its indoor cage and the dog, with swollen eyes, seemed to stare at them through a back window. And then the power cut out, the impromptu blackout plunging the house into darkness while every other home in the street remained lit. Some twenty seconds later the lights flickered back to life and with them a music track on the CD player. Turner turned off the music.

‘We looked at each other and thought, “Shit, that was a bit freaky,”’ Turner recalled.

Fifteen minutes later the power died again. Darkness. An eerie silence. Turner felt some sort of presence.

‘The rabbit was going crazy.’

The lights came to life again—and so did the music. The same music. Again Turner turned it off. Ten minutes later the power died again. The rest of the street remained lit. And then the lights came back to life, along with that music.

‘I don’t know what it was but I still remember the music,’ Turner admitted. ‘In all my years of policing it was the most bizarre thing I’d experienced. The house was horrible. There’s no question in my mind that Raechel was there while we were there that night. I just can’t explain it.’

Raechel Renee Betts was born on 5 January 1982. In her teenage years she left her mother Sandra’s home in Lismore, New South Wales, and moved in with her grandparents, Neville and Doreen Betts, in the Melbourne suburb of Ivanhoe. After high school she completed a Bachelor of Education at RMIT.

As a young woman engaged to be married, Raechel Betts was told she would have extreme difficulty bearing children. That news hit her hard, and left her bitterly disappointed.

‘She wished to have her own children but was worried her troubles with polycystic ovarian syndrome and cervical dysplasia would prevent this,’ Sandra Betts said in her victim impact statement.

As a substitute, Raechel channeled her energies towards other people’s children. She became a qualified school teacher and earned additional early learning qualifications. Up until the end of 2008 she worked at a childcare centre and oversaw an after-school program.

‘Raechel could have earned a much higher wage as a teacher in primary or high schools,’ Sandra wrote in her impact statement, which she recited in full in the Victorian Supreme Court. ‘She chose to work in early childhood education because she loved the rewarding affection and loyalty that little children would show her. Raechel kept every picture, letter, card and note given to her by any child.’

Dismemberment victim Raechel Betts in happier times.

Raechel also took on the role of primary carer of two teenage girls—whom we shall call Kylie and Kate. The two teens came to Raechel ‘with troubles’, according to Sandra Betts.

‘These two young friends had been expelled from their school and had family problems,’ Sandra said in her statement.

Raechel got them back into schooling and helped them study. She arranged dental appointments for them, fed them and clothed them. She ensured they continued their sports activities, organised their birthday parties and drove them to school. One of the girls began to improve so well at school that she was put up a year level.

Raechel, who also sponsored a child through World Vision, was described as a mother-figure to Kylie and Kate. With their parents’ permission, the teens moved into a home in the middle-class suburb of Heidelberg with Raechel and another woman. By that stage Raechel’s engagement had ended and, for reasons only known to Raechel, she waded into the world of drug dealing. At first she was a small-time dealer but later moved bigger quantities. The murky realm consumed her and by the end of 2008, Raechel had quit her cherished childcare job to traffic methylamphetamine, ecstasy, cannabis and other illicit drugs. By February 2009, Raechel and the teenage girls had moved to a house in Doncaster East. According to a Supreme Court judge, Raechel sold drugs from that address with a bloke she was having sex with.

‘I thought she was very interesting,’ that male friend, whom we shall call Vince, said in a police statement. ‘She liked drums. She liked music. She liked cars. She was like a female version of me … I know she liked fishing. Her Facebook site has lots of photos of her fishing with the girls.’

Vince had a long-term girlfriend during the time he was sleeping with Raechel. He was a drug user, but denied to police that he ever sold drugs.

‘I tried some of Raechel’s ice at one stage,’ he told police.

Raechel was using marijuana flat out at that stage and she was into pills, maybe a little bit of ice. She kept telling stories about people who were selling cocaine, who had gone missing. It was like an episode of The Sopranos. She would message me things that didn’t make any sense.

One of Raechel’s suppliers was John Coombes, a paroled double killer by that stage. He had an ability to charm younger, impressionable people.

‘I knew that Raechel knew John previously,’ Vince said in his police statement. ‘Raechel had told me that her dad knew John from when they were in the army together. I didn’t know if this story was true.’

According to Sandra Betts, Coombes ‘recruited’ her daughter at a vulnerable time in her life. ‘She was under financial duress, supporting and assisting two young women and having to quit one job due to fatigue and losing the other,’ Sandra wrote in her impact statement. ‘She was suffering emotional stress since the ending of her relationship with her fiancé and the loss [on medical advice] of the child she wished to have.’

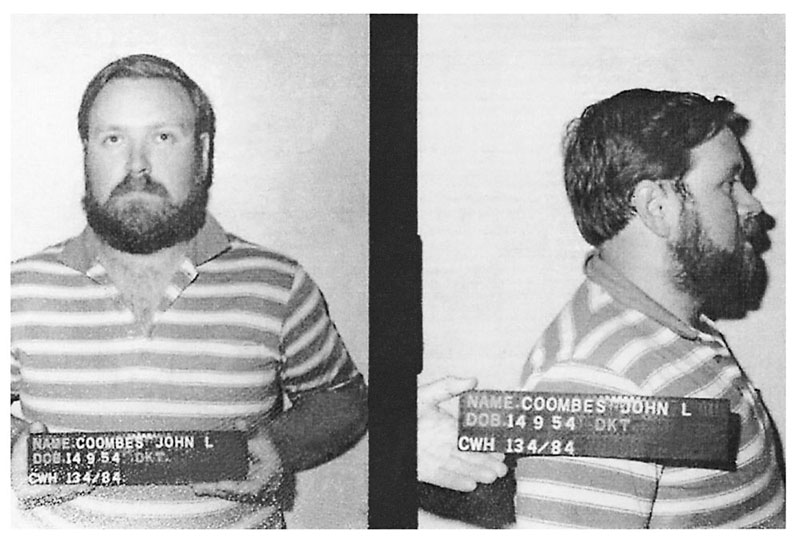

John Leslie Coombes was a sadistic killer. He was into mutilation and disintegration. He liked to see his victims end in pieces.

Coombes was born on 14 September 1954; his mother abandoned him and his infant twin brother in a boarding house. After his brother was adopted, according to prison psychology reports, Coombes’s father returned from overseas to claim him. His father remarried and moved the family to inner-city Richmond. According to reports, that marriage failed and Coombes’s father moved himself and the boy to the idyllic bayside suburb of Edithvale. But things were not so idyllic. Coombes did not get along with his dad’s new partner.

‘Mr Coombes reported that he had significant problems with that lady, indicating that she was an aggressive and evil lady whom he hated,’ the prison psychiatrist wrote.

That woman killed herself when Coombes was seven. He practically celebrated the death.

He left school after Year 10 at age fifteen and joined the army three years later after a failed apprenticeship as a mechanic. He served as an army truck driver in the Royal Australian Corps of Transport until age twenty-one. According to his story, he was discharged in 1974 after sustaining a head injury in a trucking accident. He had married at the age of twenty and had two children. He worked numerous jobs over the following years, including as a chef and hotel manager in Sydney. He was an avid fisherman.

At home, he was violent towards his wife and kids. Sandra Coombes was sometimes taken to hospital with fractured bones.

‘Our marriage was not a happy one,’ she once told detectives. ‘John would also threaten that if I left him he would find us and he would kill the children in front of me and then he would kill me.’

Coombes’s first murder victim was a man named Michael Peter Speirani. He killed Speirani on 26 February 1984. Coombes and a mate of his took Speirani, aged twenty, out on a fishing boat with a plan to bash him and throw him overboard because he was dating the mate’s sister. Supreme Court judge Justice Geoffrey Nettle said:

According to a version … which you gave to prison authorities in 2004 when you were seeking parole, you killed Speirani because he had sodomised [your friend’s] 15-year-old sister. In any event, the plea … was that, after you had thrown Speirani overboard you would then pick him up and rescue him and warn him to stay away [from the girl].

But, while out on the boat, Coombes lost control and stabbed Speirani to death. After throwing the body into the water he then took pleasure in driving the boat’s propeller into Speirani to mutilate him. The remains would never be found.

‘John said they had run over Michael with the propeller and that they had dragged his body to the side of the boat and that John had sliced Michael up a bit so that the fish could finish the job,’ Sandra Coombes told police investigators at the time.

Coombes made his wife clean the boat the next day.

‘I felt sick and scared,’ Sandra Coombes told police. ‘I saw there was dried blood on the gunnel rails. There were splotches everywhere but the majority of the blood was on the starboard side and there was also a handprint in blood on the rear wash wall.’

Nine months after murdering Speirani, on 17 November 1984, Coombes killed forty-four-year-old Henry Desmond Kells. Coombes and a friend held a grudge against Kells because he had been drinking with the friend’s landlady. Coombes and his pal drank heavily before travelling to Kells’s bungalow to bash him. Coombes again lost self-control, stabbing Kells multiple times and mutilating him. In 1985, Justice Barry Beach sentenced Coombes to life imprisonment without parole for the sadistic Kells killing. Three years later, at the age of thirty-four, Coombes and another prisoner—a convicted double killer—escaped from Ararat Prison by placing a water pipe across the inner and outer security fences and crawling to freedom. The pair managed to elude a dragnet, and were found three days later armed and hiding out on a goods train near Mildura. Coombes was returned to Pentridge Prison rather than the less-secure Ararat jail.

In April 1990, Coombes applied for a minimum term on the Desmond Kells murder sentence. A psychiatrist found that a head injury Coombes had received in the military truck crash back in 1974 caused a traumatic nervous condition that in turn triggered aggression. That aggression, combined with drugs and alcohol, according to the psychologist, led to Coombes’s murderous actions. A senior corrections officer stated in a report: ‘In spite of his offence, which did not seem to be premeditated, he does not seem to pose a substantial threat to the community.’

Hearing the application, Justice Beach considered as a mitigating factor the fact that Coombes was a heavy drinker and hardcore prescription drug user at the time he killed Kells. ‘I think it would be fair to say that at the time Kells met his death, the applicant was not in a normal and rational frame of mind.’

The judge—who at that stage was unaware that Coombes had already committed murder—also cited Coombes’s ‘disturbed’ life as a youngster and his marriage break-up as other mitigating factors. He fixed a minimum term of eleven years. Coombes was released on parole in October 1996.

Two months later he was arrested and charged with the 26 February 1984 murder of Michael Speirani, thanks to fresh information provided to police. In 1998 Justice Bernard Teague had a chance to jail the evil Coombes for good, but instead handed him a fifteen-year maximum term with a ten-year minimum. While Teague agreed that the two murders were ‘high in the scale of what is horrifying and abhorrent’, he decided that they ‘lacked the chilling, cold-blooded premeditated elements of the most abhorrent’. Teague was told that Coombes’s prospects of rehabilitation were good and, like Justice Beach before him, found that Coombes’s moral culpability was reduced by his mental condition.

An early mugshot of triple killer Coombes.

‘There is also other evidence which suggests that what you did [to Speirani] in 1984 was to some degree the product of alcoholism and other health problems no longer pressing and, more significantly, that there are clear indications of your having been rehabilitated,’ Teague said.

Put shortly, the evidence indicates that the period of imprisonment between 1988 and 1996 has had a strongly maturing and stabilising effect upon you. You had only a limited period on parole from November 1996 but the indications during that period were favourable … Although I do not propose to go into the details, I would also note that I have had regard to other matters affecting your position as at February 1984, including your difficult upbringing, your chequered employment history, the head injuries suffered in a 1974 motor vehicle collision and your alcoholism.

Unfortunately for Raechel Betts, Coombes walked from jail on parole in early 2007. He weaseled his way into the drug scene and established himself as a supplier. Due to his corpulent figure, florid cheeks and white beard, he became known around the traps as ‘Santa’. He started seeing an older woman, although her daughter took an immediate dislike to him. For Coombes, it seems, women were his playthings.

‘There is some suggestion that you sought to persuade Raechel Betts to become your mistress, too, although there is insufficient evidence of that for me to conclude it was so,’ Justice Nettle would later say.

Coombes moved into a public housing flat in Preston upon becoming eligible. While there, he started up a cottage drug industry.

‘Coombes had many customers attend this address to either collect drugs to distribute or drop off drugs to be distributed,’ the police summary stated. ‘Coombes also had the users attend to make purchases.’

In April 2009, while living in Doncaster East, Raechel asked a platonic male friend, David Gould, if he could get her some ‘hardware’. Gould knew she meant a pistol.

‘I know weapons very well as I was in the navy reserve cadets,’ Gould said in his police statement.

She told me that she needed guns for protection. I told her that I don’t deal with anyone who deals in firearms. She wouldn’t tell me any more as to why she needed protection. She was a bit flighty but not scared.

Raechel started making claims that she, Kylie and Kate had been burgled, drugged and sexually assaulted. She claimed their food had been tampered with and the sexual assaults filmed and posted on certain websites.

‘Raechel called me and was hysterical and crying,’ Gould stated. ‘There was self loathing and fear … They felt that nowhere was safe and that they were being followed.’

Gould took Raechel and the teenage girls in and collected a sample of the supposedly laced food. Gould’s wife took Raechel and the teenagers to a local medical centre for examination. Fearing Raechel was possibly suicidal, based on a letter she had written, her grandfather, Neville Betts, contacted a Crisis Assessment Team. They detained Raechel on 11 June 2009 under the provisions of the Mental Health Act and involuntarily admitted her to the Northern Hospital as a patient suffering drug-induced psychosis. The food that Raechel claimed was laced was tested and found to be normal. No images of her or the teenagers could be found on any suggested websites.

Raechel was discharged on 18 June into the care of her mother. After holding a party at her mum’s home—which Sandra closed down due to drug use—Raechel and the teenagers moved in with Kate’s mother in a north-western suburb. On 10 August, Raechel spent the night with an old school friend named Donteaba Gunn, who later said Raechel acted strangely. The next day Raechel took a call from a man she called John. Raechel told Gunn that John said he had a ‘surprise’ for her. Raechel told Kylie that she was going fishing with John.

‘[Kylie] took that to be code for going away to do “drug business”,’ Justice Nettle would say.

In her police statement, Kylie said:

She told me that she was going away with John but she didn’t really want to go. She seemed a bit fed up. She was getting fed up with the way John had been treating her. She felt like she was previously the favourite drug runner for John but now, because she couldn’t off load as much product for him, she felt like a failure. She believed that John wasn’t happy with her. She believed that she would be replaced … I got the impression that Raechel may have been right and that John didn’t think as much of her towards the end.

There was also the suggestion that Coombes wanted to pull Raechel on as a mistress.

Kylie recalled a list Raechel once showed her. It consisted of three names: names of people Raechel was said to have not liked very much. According to one of Kylie’s police statements, one was a bloke Raechel described as ‘creepy’. He was said to carry child pornography on a laptop computer and alleged to have stolen drugs from Raechel. (‘He never hurt me in any way,’ Kylie said.)

The second name on the list was that of a woman who was said to have smoked ice in crack pipes in front of her small boy, and made wild accusations about her boyfriend locking her and the child up, and also urinating on them. That woman was also said to have shot up heroin at Raechel’s house, only to later deny doing so. ‘Raechel was offended by that,’ Kylie stated. ‘She hated heroin users.’

The third name was that of a man who was said to have made sexual advances towards Raechel and the two young teenagers.

‘Raechel told me that she wanted [those three] to be sorted out,’ Kylie said in the police statement. ‘She told me she’d given a list of names to John Coombes. I can’t remember the exact conversation in relation to the list but I was under the impression that she had asked him to sort out these people for her.’

Kylie said she was shocked by a conversation she overheard in which Coombes explained to Raechel different ways to dispose of bodies. Kylie said she was ‘gobsmacked’.

They talked about dismembering bodies. They talked about popping out limbs and then using fish wire to cut the skin right open. They discussed how to dispose of bodies as well. I was just gobsmacked as to how they could think of such things to do to a human body … One thing they talked about was putting say an arm into a container full of something like acid, which kills all forms of DNA. John mentioned this. He talked about meat grinders and using them to dispose of bodies. He talked about cutting off fingers and then cauterising the hand so it doesn’t bleed out.

Sandra Betts had pleaded with her daughter to leave Coombes and her other northern-suburbs associates behind. Sandra’s gut told her they were bad news. It seems Raechel may have felt the same and had decided to leave their circle.

‘Raechel had sought the assistance of a financial advisor with Anglicare to have her superannuation released so that she could pay off debts, particularly to John Coombes, and probably then leave Melbourne,’ Sandra Betts explained in her victim statement.

She had plans to go to Queensland where her father had bought a property, to work in Queensland at a school or childcare centre. She had also discussed with me her plans to do a course in business management. This qualification would have put her in an excellent position to run childcare centres, rather than just work in them as an employee—a career move that I was encouraging her to take.

She was only days away from being free of any association with John Leslie Coombes and others she was worried about being associated with. She was very close to implementing her plans to get back on a successful path with her career and life—away from danger.

I had advised Raechel to not have any contact, even by phone, with anyone associated with drugs or debts and to keep quiet about her whereabouts … I especially believed it was not safe for her in Melbourne’s north and told her to come home to my house where I believed she would be safe. My last words to her were, ‘Please come home. You are not safe in that part of Melbourne … Please come home. You are not safe over there. I love you.’

On the afternoon of Tuesday, 11 August 2009, Raechel Betts packed a bag and told Kylie and Kate that she would be back in forty-eight hours after the ‘fishing’ expedition with Coombes. That was the last time the teenagers saw Raechel. It was about 6 pm when Betts met with Coombes, as planned. Strangely, she left her wallet in her car before she climbed into his Nissan Pulsar sedan. He drove her to a house at Wimbledon Heights on Phillip Island— some 140 kilometres south of Melbourne. It was a three-bedroom weatherboard rented by a woman by the name of Nicole Godfrey. In her twenties, Godfrey was another of Coombes’s acolytes. Born in Queensland, she had moved to Melbourne some time between 2003 and 2006.

‘Your life appears to have been rather aimless,’ Justice Paul Coghlan would say when dealing with her in the Supreme Court.

Nicole Godfrey worked as a barmaid and had experienced at least one abusive relationship. A woman with veterinary nursing experience, Godfrey had returned to Queensland mid-2008, only to return to Victoria later that year—when she met Coombes while living in shared accommodation. She should have stayed in the Sunshine State. Godfrey, working in a clothing shop in 2009, looked upon Coombes as a kind man who had helped her in Melbourne. Coombes was the classic wolf in sheep’s clothing.

What happened after Coombes and Raechel arrived at Godfrey’s Phillip Island house is not entirely known, other than Raechel, at age twenty-seven, met an untimely and grisly death.

In a nutshell, Coombes strangled her on a bed and moved the body to the bath where he dismembered her with knives. The process took over a day, during which time a salesman, or similar, visited the home.

‘I don’t think he was an insurance salesman,’ Coombes later told Homicide Squad detectives. ‘I think he had something to do with the power or gas or something. He wore a brown-coloured suit. I do remember that.’

Coombes stuffed Raechel’s body parts in garbage bags and drove them to nearby Newhaven Pier. The bags were thrown into the bay. The full gory details of the murder, dismemberment and dumping of the body parts would later shock all concerned.

Later in the week after Raechel left, Kylie and Kate began to wonder when she would return.

‘I didn’t think too much of it because I knew Raechel was away with John,’ Kylie said in a police statement.

We certainly trusted John at that time. It was around the Friday when [Kate] and I had lots of chats about what to do and we decided that we wouldn’t tell the police—or the ‘popo’ as we called them—[that she had gone to see John] because this would definitely get Raechel into trouble and there would be a million questions asked … I just expected Raechel to walk back in the door, although I was becoming worried.

Kylie rang Coombes. ‘I found it odd at the time that John had answered his phone no problem but that Raechel’s phones were all “out of range”,’ she said in her statement. ‘He then invited us to come down on the Friday night for dinner.’

The two teenagers went to the Preston flat.

‘I remember seeing in John’s unit behind the couch, next to the window, a hedge trimmer, a chainsaw and a whole heap of cloth tied up in butcher’s string,’ Kylie stated.

I didn’t say anything to John about it and I didn’t discuss it. I wondered at the time whether he might have used that stuff on Raechel but didn’t want to think about it. I was really stunned and didn’t know what to think.

As the mystery of Raechel’s whereabouts deepened, some of her body began to surface. A lone jogger ran across a severed left leg, less than a kilometre from Newhaven Pier, on 16 August. Detective Tom Hogan, of the Homicide Squad, travelled to San Remo police station and liaised with other Homicide members and local detectives. The following day, the captain of the Sorrento ferry spotted the other leg floating in the water. Despite the water police and police helicopter scouring the area, the limb was never recovered. Less than three weeks later a different jogger found two pieces of Raechel’s flesh— one sporting a distinctive tattoo—on nearby Ventnor Beach. Police had themselves a homicide. A gruesome one. A pathologist decided Raechel’s killer was skilled in the use of knives.

‘I was deeply shocked to see the tattoo from her left foot in the news,’ Sandra Betts recalled. ‘I was intensely fearful that it was her leg that had been found at Newhaven Beach. I acted immediately after recognising the tattoo to try to contact her, to check on her safety and whereabouts. I became increasingly distraught.’

It was 20 August when Hogan was briefed about a missing persons report filed that morning. It related to a Raechel Betts—a twenty-seven-year-old Epping woman. Hogan and Detective Sergeant Steve Martin travelled to the Epping address with forensics officers. While the detectives took statements from Kylie and Kate, the forensics team collected DNA samples from Raechel’s room for comparison with the recovered leg.

‘Waiting for news of the DNA results to confirm or deny her death, mutilation and dismemberment—I had a sense of dread and of surreal disconnection from people and events,’ Sandra Betts stated.

Kylie knew that Raechel’s return date was well overdue. There had been no word from her but, out of a misguided sense of loyalty and a well-founded level of fear, she and Kate felt they had to stay silent about John Coombes.

‘Raechel wanted me to “cover her arse” when she was gone,’ Kylie said in her police statement.

What I mean by that is, [a family friend] didn’t know that Raechel was heavily into selling drugs, nor did Raechel’s grandparents. I knew my job was to tell the truth about Raechel’s whereabouts during the time she was to be away … [but] I wanted to be loyal to Raechel and didn’t want to get her into trouble. [Kate] was basically doing what I was doing: covering for Raechel.

Kylie’s fears for her own safety, and that of Kate, grew.

As time went on, I became more paranoid that there were going to be repercussions for me if I told police exactly what I knew. John obviously knew that I knew from the beginning that Raechel had gone away with him. John, at least after that dinner on Friday 14 August, knew that [Kate] knew as well. I was scared also because John knew so much about us—where we lived, what school we went to. He’d met most of our friends. He knew so much about Raechel’s grandparents. He knew where they lived. It seemed a lot safer for all concerned to play dumb and not admit to what I knew … I also believed my input about my knowledge to police wasn’t hugely important because it appeared that they were investigating John at that stage anyway. It may sound strange, but I was worried that John may have somehow bugged the house and may have been listening to my conversations to the police when they were asking about Raechel’s disappearance. I felt that if I said the wrong thing, it wouldn’t take much for John to jemmy my window and kill me too. I knew John knew a lot of people and had a bit of influence in the drug using/selling community and he could have got people to harm us or even lie for him. Around this time my dad got hit by a bit of wood by someone. It might have been a burglary gone wrong but I thought to myself maybe it was related to Raechel’s disappearance.

Rather than try to avoid Coombes after the grisly murder, Nicole Godfrey maintained contact with him. They even started having sex.

‘In one call they discuss what Coombes did to Godfrey with breakfast cereal,’ a police document stated. ‘The sex talk continued for some time … at the end of the call she says she will let him know when the GP bikes are on at Phillip Island.’

Saucy text messages also flew between the two. The document continues: ‘Other text messages between them occur in which they discuss missing each other.’

Homicide Squad detectives first questioned Coombes on 21 August. He denied being at the island on the nights of 11 and 12 August. The following month, on 29 September, Raechel’s family said goodbye to her at a funeral service attended by some four hundred mourners. All they had to bury was a leg and some flesh.

‘Her life has been stolen from her and stolen from us,’ Sandra told the congregation. ‘I have lost my true love; my first true love. Her sisters have lost their mentor and confidante. For us the hurt is almost unbearable.’

Sandra also pleaded for information. ‘I think there could have been some people who might have known more than they have said,’ she said,

and it would be a hell of a lot better if they came forward and informed the police about what they know. When something like this remains unresolved, your faith in society, your faith in police and your faith in so many things is rocked.

But the investigating detectives were not rocked. Hogan and detective Leigh Smyth paid Coombes a visit on 30 October. He again denied being at the island, adding that he helped Godfrey with her car, which he said broke down somewhere near Cranbourne. Homicide detectives and forensic examiners combed Godfrey’s Wimbledon Heights house in late October. They arrested Coombes on 2 November and placed him in the squad car.

‘Coombes paused for some time and appeared to be attempting to say something, but couldn’t bring himself to do so,’ Hogan said in his statement. ‘He appeared to be attempting to control his emotions.’

Smyth spoke up in the car at that point.

SMYTH: The hardest part is actually saying it.

COOMBES: She just pushed my buttons.

SMYTH: Once you say it, it gets a lot easier. It’s just the first words.

COOMBES: Yeah, I know … I killed her. She got me so fuckin’ angry. She taunted me.

In the Homicide Squad interview room, Hogan provided Coombes with a cup of coffee and asked if he wanted a lawyer.

‘It’s too late for that,’ Coombes replied, before opening up.

Coombes gave two records of interview: one at the Homicide Squad office and the second at Barwon Prison—during which he agreed to draw a diagram of how he dismembered Raechel’s body. He admitted having taken Raechel to the Phillip Island house. He claimed they went there to discuss a plan to kill or maim three men Raechel said had sexually assaulted her and the two teenage girls. Coombes told the detectives that he and Raechel arrived there just after midnight and that he introduced her to Godfrey before all three drank coffee and listened to music. He said Raechel later went to bed in the spare room but called him into her room to further talk about the claimed kill plot, which he described to police as a ‘plan to either cut someone’s balls out or cut their fucking heads off’.

According to his first version given to police, he sat next to Raechel with his arm around her and she admitted that she had allowed Kylie and Kate to be sexually tampered with in order to pay off debts. In that version Coombes claimed he became angered by the alleged comments. In his second version to police on 23 December, he claimed that he and Raechel went to Phillip Island to ‘organise drug stuff’ and that Raechel told him she could set up Kylie as his sexual plaything if he played his cards right. In a secretly recorded phone conversation with the woman he had first moved in with after being paroled in 2007, Coombes said he could not remember what Raechel’s last words were. Coombes would later tell a consultant psychologist that they went to Phillip Island because he thought it would be a good spot for Raechel to establish herself as a drug dealer, but made no mention of the claimed kill plot.

‘As in the first version [you gave Homicide detectives],’ Justice Nettle would say when sentencing Coombes,

you said that the deceased [Raechel] showed you some pornographic images while you were en route to Phillip Island but, in contradiction to the other versions, you added that later, as Raechel lay on the bed at Phillip Island, she showed you further images of young women being sexually abused and told you that, if you played your cards right, you could also be involved. You implied it was that which triggered the killing.

Justice Nettle disregarded the notion that Raechel would have subjected Kylie and Kate to any harm or degradation.

‘The weight of evidence is that the deceased was deeply attached to both girls and spent what money she had in providing for them,’ Nettle said.

Indeed, it appears reasonably possible that the main reason she gave up her work as a teacher and took to drug dealing full time was to provide for the girls while spending more time with them. Among other evidence to that effect, the deceased’s good friend, David Gould, expressed the opinion, based on his observations of the way in which the deceased cared for the girls, that it was inconceivable that she would have allowed them to be sexually abused for financial advantage. Mr Gould’s observations were that the deceased devoted herself to the girls’ welfare to the point of her own personal detriment.

Gould told police:

I heard that the guy charged with Raechel’s murder said he did it because Raechel allowed the girls to be raped in order to make money—this would be absolute rubbish. I know that Raechel had these girls’ best interests at heart. She wanted to be a mother so badly … She loved children and devoted her life to looking after them. This was why she started to sell drugs as she needed money to look after the two girls.

Regardless of Coombes’s fabricated reasons for killing Raechel, he did describe the process.

She lifted her chin, like she wanted a cuddle and then I straddled her … put a fuckin’ sleeper hold on her and I just fuckin’ hung on. I was so fuckin’ angry. How could you fuckin’ cuddle that?

He added that Raechel kicked a bit as he strangled her. In cold fashion he described his technique.

It’s a figure-four leg lock, they call it in wrestling. It’s across the front and you take them around the neck, the other hand up and tilt the head over. I believe it … cuts off the air if you push it correctly with the palm of your hand. It prevents anything from getting through there. It’s fairly quick. That’s what they say. In reality it’s a little bit longer.

Coombes reckoned he may have broken Raechel’s neck. He said he choked her so hard that his hand cramped up.

I’m not a pathologist and that but from what the army tells us, if you’re strangling someone and they take quite a while to die, the bladder, the bowel, everything goes. But there was only a small amount of urine on her jeans.

Coombes was left lying with a warm corpse.

‘I know it is a human being, but the soul was gone,’ he told police. ‘And I know I am responsible for taking that fucking soul.’

He described what he did next.

I pulled her through to the bathroom. I got her clothes and everything off. I put ’em in the bath … I think I got Nicky [Godfrey] to make me a cup of coffee … or some fuckin’ stupid thing. I think I tried to pick her [Raechel] up. Yeah. One stage there she was dead heavy. I thought, ‘Oh fuck’. That’s when I decided then to—I went out and had a look in my car. Fuckin’ found a set of—in a box, a set of knife blades.

When I came back inside I asked Nicky if she had garbage bags … and put her [Raechel] into the bath and then just stopped and thought, ‘What the hell am I goin’ to do here? How the hell do I go about this?’

Using sash-type cord he had also brought in from his car, Coombes said he tied Raechel’s feet to the taps.

‘It was cheap Chinese shit … but it was strong enough to hold her feet up onto the tap and suited what I had to do,’ Coombes continued.

He then started cutting through skin, muscle and bone, hacking Raechel’s body into pieces and pulling her apart. Godfrey told police that Coombes asked her if she would like to watch. She said he asked her at one point, ‘Do you want to come in and do a dissection?’

‘I know she was chopped up in the bathroom,’ Godfrey admitted to detectives. ‘He took her in the bathroom because I was in bed and I had the TV on a little bit and I had my hands on my ears.’

But Godfrey was not able to block out everything. She could still hear sickening ‘pops’ and ‘cracks’ as Coombes pulled Raechel apart.

‘[There was] like popping,’ Godfrey would explain. ‘I’ve had my arm dislocated before and I know damn well what it sounds like when you pop a joint—and I could hear it.’

To sate a depraved desire, Coombes hacked off Raechel’s breasts. He became excited, or his anger rose, as he mentioned this to the police.

‘“You don’t deserve to die as a fucking woman,” I think I said to meself,’ he recounted. ‘There you go. I’m getting me anger back again.’

In his second version to police, he tried to justify the dismemberment.

I had no other way of doing it … I was trying to picture it as like just the life has gone. She’s dead. It’s a piece of meat. Do it that way. Work on it like a piece of meat. Make the cuts. Separate the joints and do what you could there … I’ve given her a quick release. It’s more than she fuckin’ deserved.

The disposal job proved a tiring task. Coombes said he had to turn on the water periodically to drain away the blood.

‘I’m not sure how far in I was,’ he told the detectives, ‘but I started getting pretty crook. I had to spew in the dunny and in the end I just had to stop.’

Coombes had a sleep, lying next to Godfrey, before rising some time on 12 August to continue the dismemberment.

I had a bit more coffee and got some garbage [bags]—I think I’ve already said I got the garbage bags. I got those garbage bags and with the pieces, I was puttin’ em in. Two or three and puttin’ them in.

Around 3 pm that day, Godfrey’s neighbour—a local panelbeater named Shayne Gislingham—returned Godfrey’s car to her home having repaired its brakes. Hearing noises inside, he knocked continuously on the front door because he needed a lift back to his workshop. Coombes, in a dressing-gown, finally opened the door. He made Gislingham wait while he got changed and then drove the guy back to work.

‘Gislingham described Coombes’ demeanour as calm and not anxious,’ the police summary stated. ‘That he engaged in conversation, but that he didn’t get a good feel about Coombes and consequently wouldn’t accept the $400 Coombes offered as payment for the job on Godfrey’s car.’

Godfrey described Coombes as looking a little tired on the night of 12 August but ‘pretty normal like nothing had happened’. Godfrey just wanted Raechel’s body out of her home.

‘I just told him I want it out of my house,’ Godfrey told police. ‘I didn’t want it there. Just get rid of it … it was making me sick.’

Coombes packed five full garbage bags into Godfrey’s car and drove to the pier in the early hours of 13 August. He tossed Raechel’s mobile phone, clothing and the knives into the water along with the bags containing the body.

‘I’m pretty sure there was only five. There was the torso and the head, and the arms and legs were in separate bags.’

An experienced fisherman, Coombes knew a thing or two about dumping offal at sea. He admitted to cutting open the bags and, before tossing all the body away, slicing through Raechel’s abdomen.

‘I did open the abdominal area but that was only to, sort of, pierce the intestines to let the gases out so they didn’t float.’

Afterwards, Coombes drove back to Godfrey’s home and scrubbed the bathroom clean with bleach-based cleaning products. He returned to his Preston flat, all the way concocting a false alibi. In a secretly recorded telephone conversation, he would later tell a lady friend it was his ‘cleanest’ kill.

‘It was just click. It’s over. Gone.’

In her police interview, Godfrey told how the sexual relationship with Coombes had bloomed after Raechel’s murder.

[We were] just talking one night and he just said, ‘You know we get along really good, not mattering about our age differences, we’d make a good partnership.’ I sort of thought about it and I said, ‘Yeah, you’re right. We sort of do. You know, we get along really well.’

Godfrey described the relationship this way: ‘I don’t know if it’s love or a fear.’

She would go on to plead guilty to attempting to pervert the course of justice for ‘knowingly making false statements to investigating police as to the whereabouts at particular times of John Leslie Coombes’. It was established that Godfrey remained in bed when Coombes and Raechel had arrived at her home—and never got up to greet them.

‘In the early hours of August 13, [Coombes] used your car to transport the remains of Ms Betts to Newhaven Pier where he threw the body parts into the fast-moving current,’ Justice Paul Coghlan confirmed.

You told police, who you knew were investigating the murder, that on the night Ms Betts disappeared Coombes had fixed your broken-down car near Cranbourne and then, after having done so, returned to his home in Preston. Eastlink records of Coombes’ car were able to assist the police relatively quickly to show that your statement of your car breaking down at Cranbourne was false.

Coombes had threatened the naïve Godfrey that she would be in ‘big trouble’ if she ever told the truth about what she knew. Coghlan sentenced the twenty-eight-year-old to three years’ jail, all of which was suspended but for the fifty-one days she had spent in custody on remand.

‘You told the police you were petrified of Coombes when you made the first [false] statement, although you got along well with him both before and after the murder,’ Coghlan told Godfrey when he sentenced her.

Your involvement in this offence and your relationship with John Coombes remains unexplained. Why you commenced a relationship with a man whom you knew to have murdered … is not easy to comprehend.

I accept that you regret what you did in supporting Mr Coombes.

In a surprise move, Coombes pleaded guilty to murdering Raechel during a morning of pre-trial argument in the Victorian Supreme Court on 2 May 2011. That afternoon, Neville Betts told the Herald Sun’s Russell Robinson that the parole system had to be reviewed after allowing a beast like Coombes back on the streets to murder again. During his plea hearing, Coombes claimed his psychological problems had stemmed from childhood when, he dubiously suggested, his mother served him up to a paedophile ring run by a headmaster of a primary school. In another effort to avoid responsibility for his horrendous crimes, he also blamed the prison hospital system for failing to diagnose the extent of his claimed psychological problems.

‘You have demonstrated in the past that you are a liar,’ Justice Nettle told him.

It is also apparent that, in the past, you have not hesitated to lie about your lifetime experiences and state of mental health in order to advance your interests. One striking example of that is that in the past you have claimed repeatedly to have suffered trauma symptoms, including intrusive recollections and disturbed dreams, the result of fire fights in which you said you were involved while on active service in Vietnam. More recently, you have felt the need to admit the fact that you never saw any military service in Vietnam.

It was submitted that Coombes deserved a sentencing discount due to his guilty plea. It was claimed that Coombes had shown remorse and had prospects of rehabilitation. Nettle slammed the lid on any chance of a sentencing discount.

‘I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the nature and gravity of your offending, your lack of remorse and the absence of a significant prospect of rehabilitation render the idea of any discount on sentence in this case inappropriate,’ Nettle said.

In my view, the dreadful nature of your crime; the consequent need for denunciation, deterrence and just punishment; and the requirement for community protection; combine to dictate that a sentence of the utmost severity is proportionate to the gravity of the offence.

During the pre-sentence plea hearing, Sandra Betts stood strong in the dock and eyeballed Coombes while telling him—and all present—of her family’s real life sentence. As she read from her victim impact statement, she spoke of her family’s anguish. The need for medication and visits to a psychologist. And ongoing grief, night terrors and nightmares.

I have had many nightmares and dreams, initially of very disturbing scenes of torture, then of the many unique expressions of Raechel’s face, then of her murderer’s amateur, inept and difficult dismemberment of her body reported to have taken twenty four hours and possibly having taken much longer … Recently I have had many dreams of a baby—my baby girl—which I cannot hold on to.

It was said that Raechel’s death had also affected her dog, Chloe. ‘She was Raechel’s companion for over seven years, sleeping on the floor beside her bed every night … Now she sleeps on the floor beside my bed,’ Sandra told the court.

Sandra said she and her family would, understandably, remain haunted for the rest of their lives.

People ask me about closure. I can assure you there is never really any closure when your loved child has been murdered. She will be missed at every family function, every Christmas, on every birthday—whenever I think of her I know I will be deprived of the chance to see her, hold her, talk with her. I think of her many times every day. The heartache is pervasive and repeated and will be with me and her family for the rest of our lives.

Sandra pleaded for Coombes to be locked up and the key to be thrown away. ‘Coombes represents a definite threat to society—of further murder and mutilation— should he ever be released,’ she told the court.

Although the ‘justice system’ has failed Raechel and her family, it should be certain not to fail another person again by ever allowing this man to walk free in the world. I do not want to find, in eleven years or so, that John Leslie Coombes has again been released and again murdered another person. My heart goes out to the Speirani family and the relatives of Henry Desmond Kells, who must be experiencing renewed trauma at the news of a further murder committed by the man who killed a member of their family.

In August 2011, Justice Nettle sentenced Coombes to life imprisonment with no chance of release. He said Coombes lacked remorse and harboured a ‘frightening predilection for homicide’.

Life without parole: John Leslie Coombes is led from the Victorian Supreme Court.

‘The nature and gravity of your offending places it in the worst category of cases of murder,’ Nettle told him.

Although you have alleged that the deceased provoked you to kill her by telling you that she was involved in the sexual assault of young girls, I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that a substantial part of what you told police and others about the deceased’s death, and particularly your allegation that she claimed to have been involved in the sexual assault of the young girls, is a fabrication or confabulation calculated to conceal the true nature and gravity of your offending … The gravity of your offending is made worse by the way in which, immediately after the killing, you hacked up the deceased’s body and cast the pieces into the sea.

It passes understanding that a sane human being could hack up and destroy the body of another as if, to use your own words, she were just a lump of meat. The heinousness of that conduct is shocking. It bespeaks an utter disregard of the law and basic norms of society and depraved inhumanity towards Raechel, her family and her loved ones.

Nettle said he had to protect the community from a man beyond rehabilitation and redemption.

Given that you have now murdered three people, given the manner and circumstances in which you killed them, and given that you killed the last of them after spending almost half your life in jail for killing the first and second of them, I am persuaded there is a real risk that, if you were afforded the opportunity to kill again, you would kill again.

Outside court after the sentence, a shaking and exhausted Sandra Betts branded Coombes a ‘cruel monster’. She said she believed he murdered Raechel because she refused to become his mistress.

‘Murder to him is better than sex,’ she said. ‘May he never be released and never have a chance to harm another human being.’

While Coombes did attempt to appeal the severity of his sentence, he had correctly summed up his ultimate fate during one of his police interviews.

‘Even though I was still trying to throw off, I knew that I was a monty to be looked at [for the murder],’ he’d said. ‘Believe me, I haven’t lost sight of the fact that, you know, three strikes and you’re fuckin’ out, boy.’

Coombes was refused leave to appeal the length of his sentence. Justice, albeit late, had finally been delivered.