2

Dealing with the tough stuff

Foundational skills

As a leader, supervisor or manager, there's one inevitable task you will encounter: the tough-stuff conversation. Whether it's addressing underperformance, critiquing work or dealing with heightened emotions, some situations with some people will be tough — there's no escaping it.

Given that we can't avoid the tough conversations, a clear choice remains. The fact that these conversations are inevitable leaves us the options to:

- passively ignore them

- actively avoid them

- have them reluctantly

- get good at them.

We think the last option is by far your best choice if you plan to stay in a leadership or management role for longer than the next month or so, particularly if you want to be a leader with influence. If, on the other hand, you're a few weeks away from handing in your notice and heading to Tuscany to eat, drink and generally be merry, then perhaps you can get away with the first three options.

For the rest of us, who have to make do with reading about Tuscany (and occasionally sitting through a bad romantic comedy about a 50-something woman rediscovering her life) and turning up to work each day, there really isn't much choice. It's imperative to get good at the tough-stuff conversations because, quite simply, your leadership legacy is defined by how well you handle them.

The two steps to getting good at the tough conversations are:

- building a better understanding of human behaviour

- learning how to modify and influence the behaviour of others.

These are foundational skills that underlie the strategies and practices, but before they can be applied we need to unpack some basic principles about why we do what we do.

Why do we do what we do?

Human behaviour can be mind-boggling at times. For every example of strength, bravery, courage and heroism in the world there are as many acts of stupidity, irrationality and downright bizarreness. Yet all behaviour can be understood in the context within which it's exhibited. At some point in our lives we have all been flabbergasted by someone's behaviour and asked ourselves, ‘Why do people act this way?' or thought, ‘I don't understand why they have done this'. But it's worth considering the broader context to understand the why behind the what.

ABC model of human behaviour

Understanding why people behave the way they do can be tricky and has essentially spawned the science of psychology. Despite human behaviour being incredibly complex and diverse, the building blocks of behaviour (what we do) are best understood through a simple yet effective tool known as the ABC model.

The ABC model breaks down and segments behaviour in order to understand it better in the same way that an editor pulls sentences apart and considers each word on its own. If you've ever studied psychology or read books on behaviour modification, you will have encountered this model. It's back-to-basics psychology, but it provides a great platform for investigating what else is at play when we're exploring human behaviour. When dealing with the tough stuff, understanding the context of someone's behaviour is important and will lead to greater success in your ability to influence that behaviour.

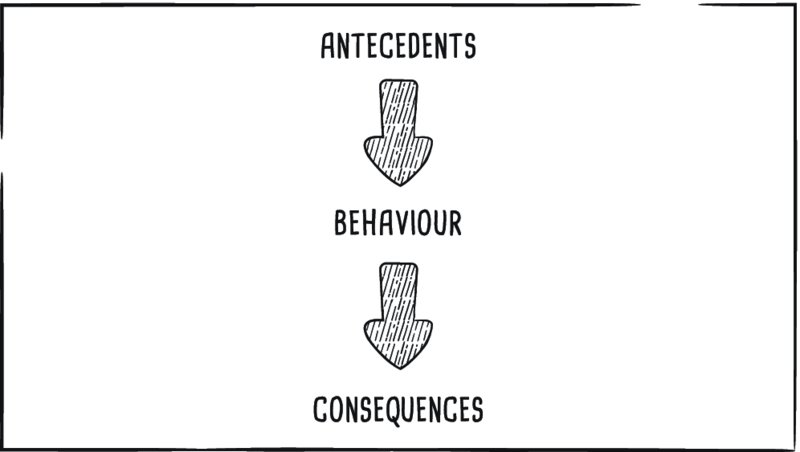

The ABC model of human behaviour (see figure 2.1) considers behaviour across three elements:

- Antecedents. Events that occur or are present before the person performs the behaviour.

- Behaviour. What the person did, or what can be directly observed in the present.

- Consequences. Events that occur after and as a result of the behaviour.

Figure 2.1: the ABC model of behaviour

‘Antecedents' is just a fancy word for ‘what comes before'. It describes the environment, conditions or factors that occur before a behaviour. Then the behaviour itself occurs and the consequences stem from that. For example, feeling tired is an antecedent for sleeping, sleeping is the behaviour and feeling rested the next day is a consequence of sleeping.

Taking this a step further, feeling rested may then become the antecedent for delivering a clear and powerful pitch to a new client (behaviour), which results in securing new business (consequence). This is how a consequence of a behaviour can become an antecedent of future behaviour: one flows from the next to the next, and so on, becoming a continuing pattern.

Understanding this pattern is integral for managers because the consequences you apply in the workplace become powerful predictors of whether or not someone will continue with a particular behaviour.

Essentially, the ABC model says that to affect behaviour (your own or that of others) you can change any of these three factors and the outcome will be directly affected.

Table 2.1 shows how managers can affect behaviour to achieve different outcomes.

Table 2.1: examples of how a manager can affect the elements of antecedents, behaviour and consequences

| What happened | How this could be changed | |

| Antecedent | Argument between two team members in the morning | Intervene during the disagreement and seek a resolution then and there |

| Behaviour | They don't speak to each other at the team meeting | Use strategic questioning to ensure both parties contribute at the meeting, removing the impasse |

| Consequence | The project they're working on together is stalled because they won't work together, and other staff complain | Address the two team members and seek a resolution to the disagreement. Gather the rest of the team and ensure their commitment to moving the project forward |

By understanding that there are antecedents (things that come before a behaviour) and consequences (things that come after a behaviour) you come to understand why people do certain things and, more usefully, why they keep doing them again and again. The antecedents and consequences provide the all-important context for understanding behaviours.

Let's look at an example of someone being drunk at a party. What are some possible antecedents to this behaviour? What are the things that led to someone being drunk at a party?

Reasons may include that they did not eat before the party, or that they drink to deal with their shyness, or that they drink when they feel angry or upset. The reasons may be social antecedents, such as peer pressure, or the drunkenness may simply be the result of consuming a lot of alcohol. It could also be all of these things occurring simultaneously. Our subject, who has had one too many, could be a shy person who's being peer pressured, hasn't had anything to eat and has drunk too much, all at the same time.

Importantly, there are always multiple antecedents for any behaviour.

Now, what might be some of the consequences of this behaviour?

The consequences might be a headache or injury, the person might embarrass themselves, or they might have a great time at the party — or the consequences might be all of the above. It could be like the movie The Hangover, in which there are plenty of consequences linked to this behaviour: a hangover that measures 9.5 on the Richter scale, no recollection of the night whatsoever, a very unfortunate tattoo and Mike Tyson's tiger in the bathroom!

As with antecedents, there are always multiple consequences for any behaviour.

Exploring antecedents

As a workplace manager or leader, at some point you will need to make changes to other people's behaviours: increased workload, fewer mistakes, greater ownership of a project, or even something as simple as asking a staff member to smile more at the front counter. The behavioural coaching you do as a manager is a vitally important component of your work.

Your success in shifting or modifying a person's behaviour is directly related to how well you understand the antecedent structure that drives the behaviour itself. You could brainstorm several strategies on how to get someone to smile at the front counter, yet if we don't know the reasons (the antecedents) for a person not smiling, they may not stand a chance of succeeding.

Given there are always multiple antecedents for any behaviour, let's look at a case study to see how understanding antecedents may help create a better resolution of a problem.

Notice what is out of character

People don't change their behaviour unless something prompts the change. Here is one of the biggest of many big takeaway lessons from this book:

If there's been a change in a person's behaviour, there must have been a change in the antecedent structure.

Written in plain–speak: if you've noticed a change in someone's behaviour, then something must be driving the change.

And here's the kicker: the clearer you can be about the drivers for change, the clearer you will be in shaping behavioural change and influencing a more desirable behaviour.

In the case study, Tali addressed Rex's behaviour directly, an admirable course of action. But she could have mapped out a better strategy, or at the very least managed the situation better by exploring the antecedents that may have driven the recent change in Rex's behaviour. By starting the conversation along the lines of, ‘Rex, I've noticed a change in your usual high standards. Is there any reason behind why you're not as punctual as usual, or why you haven't been putting your hand up for project work?' Tali could have opened the door for Rex to share the antecedents that may be contributing towards his changed behaviour.

You will not always get answers, but in many cases you will. By simply addressing the behaviours without first considering the antecedents that drive the behaviour (as Tali initially did), we lock ourselves into a behaviour–change strategy that may not match the antecedents that are present.

By considering what else is going on in a person's life, you can begin to understand the broader context of their behaviour. Wherever possible, look at other factors that may be antecedents, because this understanding will help deliver a better outcome.

Behaviour modification

One of the roles of any manager is to influence, guide, support, adjust and ultimately modify the behaviour of others. In a nutshell, behaviour modification is the use of specific techniques aimed at increasing or decreasing certain behaviours.

What is critically important for effective management is to recognise and be conscious of the strategies you're currently employing. You are influencing and modifying the behaviour of others, but you may not be conscious of the strategies you're using. That makes it difficult to know how to repeat a strategy if it works, or what to change if it doesn't. What's important is to learn how to be strategic about influencing the behaviour of those you are managing in the most effective manner.

The two strategies used widely in modifying human behaviour are:

- reinforcement

- punishment.

While many people recognise these two terms, few understand the correct time and context for employing them effectively.

What do we mean by reinforcement and punishment?

Most people associate the terms ‘reinforcement' and ‘punishment' with good and bad, positive and negative. These are the social definitions often connected to these words, but they're not true definitions.

This misunderstanding is a bit like our misunderstanding of the words ‘extrovert' and ‘introvert'. Most people think the extrovert is the really loud person, the life of the party who always has a crowd around them and is over the top; and the introvert is the quiet, shy bookworm who likes to sit in a corner and do their own thing, and generally likes being left alone. That's how extroverts and introverts are defined socially, but the true definitions of those two words — particularly when Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, popularised them — actually relate to where our energy comes from. Extroverts get their energy from the world around them: people, hobbies, things, other interests, and so on. Introverts, on the other hand, gain their energy from their inner world of thoughts and ideas. The true definition is decidedly different from the social definition.

Back to reinforcement and punishment. They aren't good and bad, and they aren't positive and negative. All these terms mean is simply to increase the occurrence of a behaviour (reinforcement), or decrease or eliminate the occurrence of a behaviour (punishment). They're not good and bad, there's no judgement around them: they mean simply to do ‘more of' or ‘less of'.

Two types of reinforcement

Reinforcement comes in two forms: positive and negative. The positive and negative do not mean good and bad, but addition and subtraction: to add or remove something to the circumstance to see an increase in the occurrence of a behaviour.

Positive reinforcement

So let's start with a very common term, positive reinforcement, and look at each component.

- ‘Positive' means to add something to the situation.

- ‘Reinforcement' aims to increase the desired behaviour.

In simple terms, a positive reinforcement strategy is one that adds something else to the equation in order to see more of the desired behaviour.

So what's the most common and arguably the best positive reinforcer known to mammals? Yep — you got it: praise (congratulations!).

Praise works phenomenally well on human beings and other mammals. If you have a dog, you know where we're coming from. Your pooch will almost starve itself for praise. And human beings will do the same. In a desert of praise we will drink the sand — it's such a key driver for us.

Other common positive reinforcers are food, rewards, money, gifts, responsibility, attention — almost anything you can add to a situation to see more of the desired behaviour.

Research about the use of different forms of praise has been done over the past 20 years, championed by Stanford researcher Carol Dweck. She reminds us that not only is praise a good thing, but certain types of praise are also far more effective in creating success in the long term. Dweck and her colleagues pointed to a phenomenon they called the ‘effort effect' — heaps of praise for the right behaviours and the quality of effort that goes into those behaviours, rather than praise for innate ability, intelligence or talent.

With regard to persistence, it turns out that when people are praised for effort, and believe that effort is the key determinant of success, they see failure as an opportunity for learning. When people are praised for their natural abilities, and believe that talent is the key determinant of success, they see failure as a reason to give up. The key is to praise people not only for the outcome but for the effort they have put into a task, and they will persist at it through barriers.

In short, giving positive reinforcement for behaviours within a person's control, rather than praising natural ability that is predetermined and out of their control, is far more effective. In professional sport you learn very quickly that if you don't regularly reinforce the behaviours you want to see on the ground, you may as well congratulate the other team on their win before the game has even started. To ensure your team wins the game, you need to reinforce regularly.

Negative reinforcement

Negative reinforcement is less common, but it is still effective and occurs in our workplaces regularly. Again, breaking down the two words that make up the term helps us gain clarity.

- ‘Negative' means to remove something from the situation.

- ‘Reinforcement' aims to increase the desired behaviour.

So, negative reinforcement is removing something to see more of the desired behaviour. Negative reinforcers are a lot rarer than positive ones, but they are still enormously effective.

You will see negative reinforcement at work if you have graduates, trainees or apprentices in your organisation. When they finish their traineeship or their apprenticeship it seems that, the moment you take away their probationary status, they step out as almost a new person — ready and confident to use their new tools.

In this case, it's the removal of something (probation) to see more of a desired behaviour (ownership or responsibility). Some organisations remove set working hours and introduce flexible hours because some people (such as those with family responsibilities) work better at certain times of the day. This is another way of getting more of something by taking something away. Removing the set working hours increases productivity and morale.

Two types of punishment

The aim of punishment, on the other hand, is to see less of a behaviour or to eliminate it. Again, we have both positive and negative punishments, and once again positive and negative mean to add or remove something respectively.

Positive punishment

Positive punishment sounds weird, doesn't it? That's because it doesn't match the social definition — it seems to be saying bad and good don't go together. Again, if we look at the two words independently the definition becomes clearer.

- ‘Positive' means to add something to the situation.

- ‘Punishment' aims to decrease or eliminate the undesired behaviour.

So while positive punishment sounds weird, we can see it's actually an everyday part of our work as a leader. In fact, you probably use it every single day!

The classic form of positive punishment is critique: ‘Not a bad job but if we could take out those spelling mistakes and those typos, Gabriel, that would be great'.

So it's adding something (commentary) to see ‘less of' something (mistakes). As managers and supervisors we actually use positive punishment quite a lot. It shouldn't be a moral judgement that someone has done something wrong, as may be implied by the word ‘punishment'.

Negative punishment

The final area to consider in these basic behaviour modification strategies is negative punishment.

- ‘Negative' means to remove something from the situation.

- ‘Punishment' aims to decrease or eliminate the undesired behaviour.

Negative punishment in the workplace is usually pretty severe. It's when we take something away to see ‘less of' something. It may be taking away responsibility or wages or it may actually be sacking someone. This is the ultimate form of negative punishment in the workplace: we don't want a certain behaviour to happen any more so we take the person away. That's the ultimate way of making sure that behaviour doesn't happen anymore.

Getting clear

Most people inadvertently use these strategies, although they're usually not sure when and where they're using them. Some executives we coach have made comments such as, ‘I'm confused. I sat down with Joanne and told her I need her to be on time to team meetings and that her lateness isn't going to be tolerated any longer. That if she continues to turn up late there'll be consequences'. At this point a smile starts creeping across our lips because we know what's coming next.

‘Then she turned up to the next team meeting and just sat there, pouting. Just sat there, didn't do anything. Unbelievable!'

Our reply? ‘You got what you asked for.'

What you've asked her for is ‘less of' (lateness) and so you're also going to get ‘less of' in a whole bunch of other areas (contribution in the meeting, for example) until the time comes when you can reinforce the behaviours and get her doing ‘more of' again.

Collateral effect

One of our favourite sayings is, ‘A rising tide lifts all ships'. And this is what happens with reinforcement and punishment. If we use a reinforcer, we actually see other behaviours increase across the board. So if you do a good job and I'm your boss and I say, ‘Oh, awesome job!', positively reinforcing the behaviours, I will actually see a rise in other behaviours elsewhere.

If I said to someone else, ‘That's not good enough, and it's really not what we do around here, so next time can you make sure there are no mistakes like this?', there's a strong likelihood we will see a drop in behaviours in all aspects of an employee's work.

Be mindful of the strategy you're using, because there are increases and decreases, not just on that singular behaviour, but in other areas as well. In the case of the executive's conversation with Joanne, getting Joanne to do ‘more of' rather than ‘less of' may be a better conversation to have. Instead of rebuking her for being late (positive punishment), the boss could assign the first agenda item in the next meeting to Joanne (so she has to be there on time) and reinforce the behaviour through praise (positive reinforcement) when she achieves the task.

Lead strategy

We believe that a high-performing workplace should have a ratio of 90 per cent reinforcement to 10 per cent punishment. Where do you think your current ratio sits? What about the ratio across your workplace?

You may have assessed this at different levels: some teams may be 80/20, some more like 50/50 and some may be more like 20/80. And all of those ratios may be serving the purpose intended. The reason we suggest the 90/10 rule — and remember we prefixed the statement with the words ‘high-performing workplace' — is because these workplaces ask people to work harder, faster, smarter. And these are all ‘more of' behaviours — more efficient, more innovative, more productive. In the high-performing workplace, our lead strategy should be reinforcement, not punishment.

These ratios are flipped in some workplaces, albeit at a cost. For instance, if a new manager walks into a ‘zero harm' workplace, which requires zero tolerance for unsafe practices, and people are operating in an unsafe or dangerous manner, they need to eliminate that behaviour. But in taking on punishment as a lead strategy, productivity is going to drop, along with other behaviours across the board. This is why many workplaces are now using behavioural safety interventions to drive safer work practices. These are programs that focus upon the thought processes involved when someone chooses to undertake a safe or unsafe act — in short, a safer workplace without the impact of the lost productivity or lost output that would accompany the implementation of punishment as a lead strategy.

Similarly, if you use reinforcement as your dominant strategy, there's going to be an increase in behaviours across the board and sometimes that actually may include things such as skylarking, or taking more risks, or similar behaviours. How many times have you seen someone rising up the corporate ladder and really going places — so they're getting reinforced a lot — and suddenly they step outside the boundary. For example, they create a policy on the run and send an email out to the entire network without first getting it signed off by their manager. Be mindful of your lead strategy, but be prepared to work with some collateral behaviours that will occur as a result.

Ensure maximum effectiveness

It's not enough to know how reinforcement and punishment work as behaviour modification strategies in our workplace. We also need to ensure maximum effectiveness of the strategies we use. What's really interesting about the words ‘maximum' and ‘effectiveness' is that there's a best-practice code that goes with them. The schedule for how reinforcement should be applied is shown in figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: the reinforcement schedule

If there doesn't appear to be a pattern, then you are correct! Reinforcement works best when it's intermittent and can't be predicted. Once a reinforcement schedule can be predicted it starts to lose its motivational effect.

Take poker machines, for example. Why are they so effective? Why do people feed their wages into them at clubs and pubs? It's because of the pokies' intermittent schedule, or reinforcement pattern. They work so well because players don't know when the machine is going to pay out, and they don't know how big the payout will be. Most problem gamblers have a couple of wins early on, which deludes them into thinking they can work the game out. They will also sit back and watch someone else using up all the bad spins and pounce on the machine like a jaguar the minute the person moves off it.

From poker machines to the workplace: if you want to get reinforcement schedules working really well, they should be implemented without rhyme or reason. Contrary to popular belief, Christmas bonuses actually aren't strong reinforcers. They are in the first year, but after that they just slip into a pattern of expectation. The same is also true for performance reviews that are attached to monetary bonuses — they're not effective motivators because the process is too predictable. This is one reason why we're seeing a shift away from purely monetary incentives — because they become an expectation rather than a reinforcer.

Praise is our best friend in managing and leading other people when it is used intermittently. For example, at the end of a project that Allan has put six months of his life into, don't say, ‘Yeah, good job, Allan,' and walk off. He is thinking, ‘Is that it?' Whereas Jo, who's been working on a spreadsheet for six minutes, doesn't expect to hear, ‘Everyone! Look at what Jo's done! It's fabulous!' Ensure your praise matches the circumstances and you'll achieve intermediate patterning. Allan's praise should be big praise! It could be anything ranging from a nomination for a public award through to a handwritten letter of gratitude for his work. Remember, small things can have a very big impact. Every situation is different, so the guiding principle is to dial up the praise for the big stuff and dial it down for the little stuff.

Consistently inconsistent

You need to be random in your use of reinforcers to achieve the best effect because consistency can reduce the effectiveness of a reinforcer.

Let's say you are appointed the new CEO of a medium-sized organisation where the previous boss was a tyrant. She was one of those bosses where you would hear her footsteps in the hallway and everyone would cringe — a Devil Wears Prada kind of boss.

As the new boss you tell yourself you're not going to be like the previous scary CEO. That's your first order of business. At the end of the first Monday you walk out into the open-plan office and say, ‘Thanks very much guys! It's been an awesome day working with you, and we're really doing some awesome stuff here. See you again tomorrow'. And off you go.

Everyone thinks, ‘Oh, that was nice, not like the old DWP (Devil Wears Prada) boss'.

At the end of Tuesday you come out and say, ‘Right guys, we're off home, thanks again. Gee we've done some fantastic work. We really got off to a great start in the week. See you all tomorrow'.

Do you see what happens to that reinforcer by Friday? It just becomes a greeting and loses its impact because it's too consistent. So make sure that you reinforce inconsistently and you punish consistently.

Consistently consistent

As you can see in figure 2.3, the pattern for punishment is again a schedule, and it's not really complicated.

Figure 2.3: the punishment schedule

For punishment to work as a strategy it has to have a consistent pattern of use. The basic rule of thumb for punishment as an effective strategy is that it has to be applied:

- immediately

- every time

- for as long as it takes.

The moment this consistent pattern turns into an inconsistent pattern, it mirrors the best reinforcement pattern and loses effectiveness. We actually reinforce the behaviour that we're trying to avoid.

Some of you may have inherited failed punishment strategies, where someone has started a punishment style and then given up, or stopped and then started again. Repeat half a dozen times and you have yourself a very resistant-to-change behaviour because it's been reinforced over a length of time.

So, punishment is a tough gig. Any parent will know just how hard it can be to stay consistent in addressing behaviours you don't want to see. It's exhausting!

It's the same in the workplace: if you're going to use punishment, commit to the schedule of consistency and see it out. It's tough, but if you don't see it through to the end, you simply get ‘more of' the very thing you want to see less of. Particularly in public-sector and large organisations, and policy-heavy workplaces, it can sometimes take years to undo the damage caused by an inconsistent punishment schedule.

Although we suggest punishment works extremely well when used the right way, we also realise that punishment as a strategy is tough work and can drain both energy and resources. So we suggest another strategy, where you can avoid punishment altogether: competing behaviours.

Competing behaviours

A competing behaviour is where we take a desired behaviour that's incompatible with an undesirable behaviour and overlay it in the circumstance.

Let's say you're a cigarette smoker and you decide that this year is the year you're going to give up. So you go to the doctor and say, ‘I really want to kick this habit. What's the best way to move forward?' One of the first things the doctor will advise? Do more exercise. Why? Because it's a classic competing behaviour. You can't really go out for a jog and smoke at the same time. If you did, a smart doctor would suggest taking up swimming! You'd have to be really inventive to smoke and swim at the same time, wouldn't you?

A workplace example of the competing behaviour strategy may be someone whose work consistently has grammar and spelling mistakes throughout it. Sure, you could go down the punishment pathway to reduce the number of mistakes, or you could look for a competing behaviour that could be used.

A desired behaviour would be for the person to employ a double-check system where they, first, print the document off for reading (diligence); and, second, give it to a peer for proofreading (collaboration) before submitting it.

Rather than using a punishment, we replace the unwanted behaviour with desired behaviours that compete directly against it. In this case, if the staff member uses diligence and collaboration (the desired behaviours) they make fewer, if any, mistakes (undesired behaviour).

Instead of punishing the behaviour, look for something you want from the person (desired behaviour) that competes with the undesired behaviour.

Meaningful work

Reinforcement, punishment and the use of a competing behaviour are three broad areas to focus on when effecting behavioural change. They all work well given the right context, but all are disabled as effective processes in the modern workplace when people lose a sense of meaning in their work. Sure, if it's a factory setting, these principles will still hold weight, but if you need higher order concepts, such as lateral thinking, problem solving and innovation from your staff, then ensuring people have an attachment to the general purpose of their work is critical.

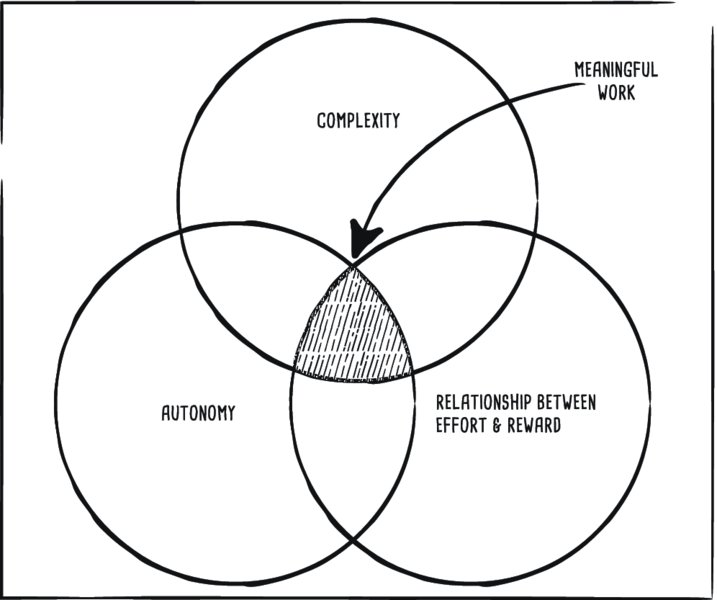

Employees who are engaged in meaningful work get things done. It's as simple as that. International best-selling author and staff writer for the New Yorker magazine Malcolm Gladwell says three things are needed to create meaningful work (see figure 2.4).

- Complexity. The work needs to have a level of complexity to be challenging.

- Autonomy. Individuals need the space to be able to do what needs to be done their way.

- Relationship between effort and reward. Is it clear and transparent that if you put in effort there will be an equivalent reward?

By the way, an expected and predicted yearly bonus that's based on whether the business has enough money rather than the effort put in doesn't create meaningful work. This type of bonus quickly becomes an expectation rather than a reward.

Figure 2.4: the three things needed to create meaningful work

Conclusion

Great leaders are those who continue to develop and grow. The ability to address and confront the tough stuff is directly related to your ability to learn, grow and develop. Understanding the foundations of why people do what they do, and knowing where to start when the need to deal with the tough stuff arises, is fundamental.

Remember to focus on the end goals and match your behaviour-modification strategies to them. Once you are clear on the direction, the steps required become much easier.