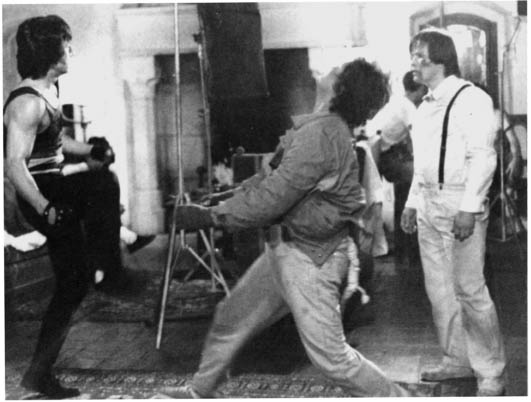

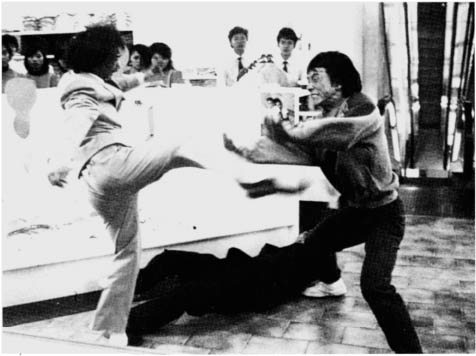

Chan and Urquidez in their classic Wheels on Meals fight. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Choosing the ten best fight scenes in Jackie’s long career was a difficult task. He has fought so many people, and with different fighting styles, camera techniques, and props. Sammo Hung’s direction also played a large part. Below are without a doubt his best matches. Given, judging these fights was based on the original Chinese versions in their original aspect ratios. The fight between Chan and Whang Inn-sik in Young Master, for example, would not have made the cut if the English version had been judged. It is missing several minutes of fight footage and the original score; furthermore, it was shown panned and scanned. The absence of wide screen in this scene completely eliminates its entertainment value.

Unfortunately, the average viewer will have a somewhat difficult time finding all of these fights the way they were meant to be seen. The simple rule is to stay away from all of the English versions unless they are the only ones available. (See also the reference section on Chinese video in the appendices.) Each fight is given with its original aspect ratio for quick reference. Anything that has a 2.35:1 aspect ratio is completely wide. 1.85:1 can be seen sans letterboxing without the quality being affected.

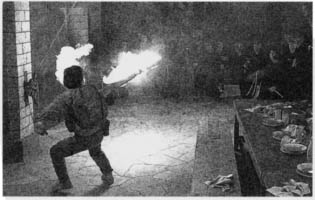

1. Wheels on Meals (1983): Jackie Chan vs. Benny “the Jet” Urquidez 1.85:1

If any fight sequence can show off Sammo Hung’s amazing abilities as an action director, it’s this classic matchup. All of the problems with American fight choreography are solved by using the subtleties of real combat: the mannerisms, setting the stage, strategizing, and creating a rhythmic trading of blows. Segment shooting, slow-motion shots, panning, and undercranking the camera are all used in Hung’s resume, edited to a breakneck pace. Hung breaks the fight up into three parts, which gives the audience what it wants without drawing the realism away by presenting a long, improbable encounter. The final element to this fight is Hung’s clear understanding of fighting techniques and how they relate to specific body types.

Sammo Hung runs through the choreography with Chan and Urquidez. (Courtesy of Sara Urquidez).

Each character is given various mannerisms in preparation. Urquidez takes off his coat and strums his suspenders while staring down Chan. As the fight progresses, he licks his lips and shakes his hands to keep loose for the bout at hand. Chan pulls off his shirt, does some knee bends, dances around a bit, and stretches out. Since Urquidez is a real fighter, Hung lets him fight as such, without weakening facial expressions, which would let his enemy know that he was injured. On the other hand, Chan grunts, wiggles his nose, and rubs his head to remedy the pain. The fight is thus given moments of lighter tone to balance out the faster segments.

Since they are fighting in a room, Chan kicks a long bench out of the way. This indicates that the two are going to fight it out without any obstacles. A large, red rug makes it almost look as if the two were fighting in a ring without ropes. The camera then pans around to the side while both men begin to circle one other to set up their strategies. While the fight is in motion, fake-outs are used to set up real maneuvers right after them.

A clever gag in the film displays the power that the audience needs to see for believability. When Urquidez pushes Chan against a table, inching him back step by step, he throws a spinning round heel kick, only to miss Chan and blow out the candles that are on the table behind him. “By the time I had to shoot that scene, I was so tired that I could only blow out one or two of the six candles. Finally, the crew came up with an idea. At the same time that I spun around, there was someone with a piece of cardboard to catch any of the remaining candles that were still lit. Believe it or not, I was able to blow them all out by myself. I spun so hard that I almost twisted my back, because I just wanted to get to the next scene.”

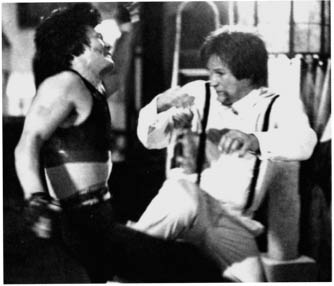

(Courtesy of Sara Urquidez)

Vitali gets a taste of his own medicine thanks to Yuen Biao. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

The fight itself was mapped out by Sammo Hung, who let both Chan and Urquidez use their appropriate skills. Benny “the Jet” Urquidez is undoubtedly the best ring fighter the world has ever seen. He was one of the most prominent kickboxers to bring traditional American boxing to the foundation of martial arts. Urquidez keeps a fairly small base, bending his knees to keep a powerful stance. In watching the scene, notice his leg movements, which spring out from the sharp rise of his knees. He also mixes it up with direct punching and powerful elbow and knee techniques. Chan’s stance is a little wider so that he can aim his kicks higher.

Though the scene was choreographed, Urquidez is quick to mention the little agreement between Chan and himself: “I remember Jackie asking me if I was a real fighter. I said yes, and then he replied, ‘Well, how hard can I hit you?’ ‘Well, I’m used to taking a lot of impact, so it depends on how real you want to make it.’ Jackie said, ‘I want it to be real!’ ‘How real?’ ‘As real as possible?’ ‘Well, I’m game for it if you are.’ We agreed that the fight was to be a give-and-take situation.” After working out together and fighting each other in two scenes prior to the climax, the two were ready to duke it out without any pulled punches. “We actually slept right there on the stage and fought that scene over the course of five days. After we rested, we would get up and go at it again. I became so involved with the fight that sometimes I forgot I was filming a movie!”

Keith Vitali, who fought Yuen Biao in the climax, remembers that Chan and Urquidez did get a little heated during their confrontation. The fact that Vitali and Urquidez, both professional fighters, hit hard was something they did not expect would agitate the crew. “They had to get their revenge,” Vitali remembers. “In my scene, Yuen Biao throws wine in my face. As the wine is stinging my eyes, he crashes a real ceramic vase over my head. When you’re watching the scene, notice the smile as I fall backward. That wasn’t acting; I was laughing to myself in astonishment that they used a real vase to literally knock me unconscious!”

Urquidez would not get away so easily. In one of the final segments, a rather tight shot shows Urquidez being clobbered with Chan’s clenched fists inside leather gloves. In a grueling fifteen takes, Chan was literally hitting Urquidez with everything he had. “I asked Benny if he was okay, and all he said was, ‘No problem!’ Benny is a superman when it comes to pain,” says Vitali.

(Courtesy of Sara Urquidez)

Whang Inn-sik catches Chan off-guard when quenching his thirst. Young Master. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

American fight choreographers should take note of the complexities of this spectacular montage of camerawork, fighting techniques, and the war itself.

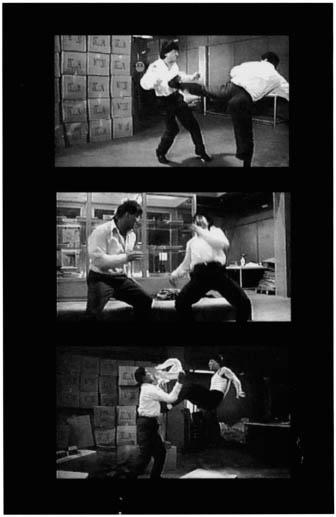

2. Young Master (1980): Jackie Chan vs. Whang Inn-sik 2.35:1

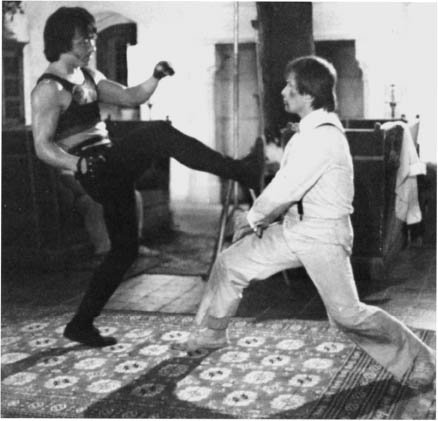

This period kung fu film’s finale ranks as having the best segment shooting with wide angles. In all the martial arts films ever made, the Korean style of hapkido has never looked better. Unlike the multitudes of kung fu fight sequences, this isn’t a bloodthirsty rite of revenge but merely an exhibition. Halfway into the film, the audience can see the power of Whang’s kicks, but his character seems to take on a monstrous form, with long, ugly hair, ragged clothes, and beady eyes. When Chan confronts him to save his friend at the end, Whang looks like an ordinary person, with nicely combed hair and appropriate attire. Thus, the scene isn’t trying to pit good guy versus bad guy in the traditional sense; fighting Whang is just something that Chan has to do. When Chan needs a drink of water or a quick rest, Whang just waits idly by until his opponent is ready to engage again. The intensity of the matchup is not an important factor, so fast-paced editing isn’t necessary. Instead the match is shot in extremely wide angles, as if to show the audience a demonstration.

And that’s precisely what Master Whang Inn-sik was doing. Hapkido practitioner Whang demonstrates all three components of the form: the traditional kicks of karate, the throws of judo, and the wrist and arm manipulations of aikido. Hapkido was actually taken from Daitoryu aiki-jujitsu, the same style from which aikido was created. Most of the combative measures of the art are not tapped into because Chan just isn’t a worthy match. Whang does use the cat stance, one of the key elements of the style. The stance has the participant keep the front leg off the ground at all times; after any kick is thrown, the leg simply moves back to that position. Whang hops at Chan, shooting his front leg at him with lightning speed, even dropping it occasionally to let the back leg get in a kick or two.

After assaulting him with kicks, Whang then moves to wrist manipulations, flipping Chan around as though he were a puppet. By applying pressure on the elbow, he works Chan over with variations of arm bars and painful wrist and hand contortions. At one point, Chan becomes so infuriatingly helpless that he jumps up and down screaming, trying to make Whang let go. Minutes of torture go by until Whang decides to go one step further with his holds by actually throwing him to the ground, still clutching the leverage points.

When Whang was kicking, Chan grabbed hold of his legs. When Whang started throwing him around, Chan grabbed hold of his body. The first fifteen minutes of this fight are spent giving Chan a lesson in the art of hapkido. One of the major flaws in many martial art fight scenes is when the good guy suddenly develops the ability to overcome the villainous opponent who had been winning the fight all along. But in Young Master, Chan doesn’t come back with some new style of kung fu. In fact, his body is so numb from the beating he is enduring that he just stands up for more punishment. With a confused look on his face, Whang continues the assault once again, but this time, Chan isn’t going down. He stands with an empty look on his face letting Whang kick him in the chest and face as hard as he can. Even more surprisingly, when Whang does get the upper hand, throwing him around like a rag doll, Chan walks away only to throw himself down in repeated intervals, showing that he can’t be injured anymore!

By running at Whang like a lunatic, Chan kicks, head-butts, pinches, and punches Whang, who finally gets a taste of his own medicine. When Whang grabs him, Chan starts kicking his legs until Whang lets go. When Whang throws him on the ground, Chan tries to fight him from the ground. In the end Chan breaks Whang’s back by folding his legs over the top him. He has apparently won the duel, but Chan’s crazed demeanor doesn’t stop there. Like a lion who toys with his deceased prey, Chan grabs Whang and thrashes him back and forth until his aggression has faded away.

The scene took over three months to shoot, and Whang and Chan would work out together morning, noon, and night to pull off ten filmed actions a day! The camera showcases the two executing countless movements of action before an alternate angle is inserted. There isn’t anything in the setting to get in the way of the fight, as they are dueling it out on a flat grassland prairie.

Some of the kicks in the film were push kicks, which means that Chan actually met Whang’s foot without receiving the impact of the force behind it. With the wide-angle shots, several cable jerks pulled the recipient of the kick from one side of the shot to the other. A cable jerk uses a cable attached to a harness fastened from the neck to the abdomen for support. One method, clearly the one used in this film, is to have about ten men just jerk the cable, pulling the person as if he or she was shot with a shotgun or kicked by Whang Inn-sik.

One of the best things about this fight is the accompanying classical music, The Planets, a suite by Holst. Also, the fight must be seen in wide screen to get the full effect of the techniques. Indirectly learning from Master Whang, Chan has often credited hapkido as being part of his martial arts foundation. Watching Whang in action, it’s easy to see why. (Chan currently trains with a hapkido master.) Whang presently resides in Canada, where he heads up the Eagle Hapkido Academy, still teaching in his sixties.

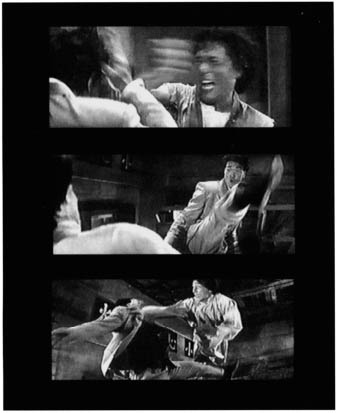

3. Heart of Dragon (1985): Jackie Chan vs. Dick Wei and Company 1.85:1

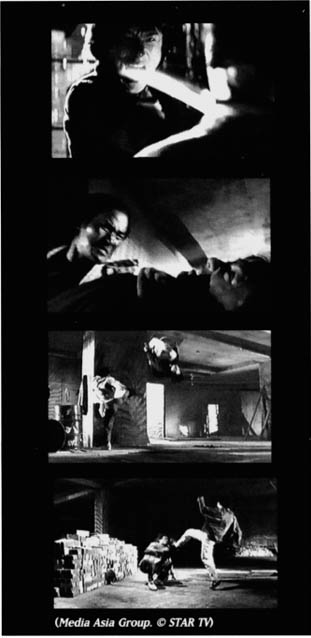

This represents a rare opportunity to see Chan as an offensive fighter. He’s not running away from anything, and everyone who comes into his path better watch out. With Sammo Hung at the helm, Chan’s potential brutality is finally unleashed without the light melodies and touches of humor that his own scenes possess. The final fight scene in Heart of Dragon is without a doubt the best use of editing and set design in Hung’s resume. Amid damp floors littered with boards and the odds and ends of a construction site, Chan and his crew must take on the seedy criminals that lurk behind every nook and cranny of a multilevel building. Chan’s part in the action is played during the middle, while his buddies shoot machine guns and blow up grenades on both ends.

With the flickering sparks of welding slicing the dark air, Chan works his way through the lower level in an uncomfortable haste. The first sign that this is not your typical Chan fight scene comes when a man holding a shovel greets him at the top of some stairs. Chan doesn’t try to fight his way past—he just pulls the trigger and blows him away. Without any warning, a combatant surprises Chan at every turn, using various weapons. Instead of fighting all of these people, Chan’s violent edge gets the best of him as he puts a machete through a guy’s neck, slams a pickax into someone’s stomach, and pierces a foe’s chest with a sharp steel rod. The manic look on Chan’s face is mesmerizing, as he becomes a dangerous character instead of a character who reacts in dangerous situations.

At one turn Chan is ambushed by Dick Wei in their fourth, and best, knock-down-and-drag-out scene together. Allowing no time for setting the mood or strategy, Hung match-cuts this fantastic duel with complete cohesiveness. The fight takes place in three different parts, each one surpassing the previous one in relentless combat. When Wei’s spinning roundhouse sends Chan bellowing back into a cluttered mess of boxes, there’s no shot of Chan’s facial expression while he tries to get up. Instead, Wei is seen running at Chan to stomp him into the ground. This is Chan’s most bloodthirsty encounter, without one single note of music to give it that dance number effect. It’s war, and the audience is left to wonder at the sheer brutality of it. Chan and Wei really look like they are trying to kill each other, unlike the bout from Wheels on Meals.

The action explodes with a fevered pitch throughout the entire scene. The complex shots give a dangerous, haunting atmosphere, men scurrying in the background with weapons in hand. Chan shoots a gun, fights with boards, and aggressively kicks ass, instead of acrobatically dodging his opponents. Not one shot in this entire sequence is wasted or flubbed in mounting Hung’s personalized brand of violence. By all means, watch the Chinese and Japanese versions of this film, which contains all of the elements that make this scene one of Chan’s best.

4. Police Story (1986): Jackie Chan vs. Fong Hak-on and Company 2.35:1

Chan virtually puts that manic character from Heart of Dragon inside of his own filmmaking style, using acrobatics and props to dilute the realism of the violence. Chan also taps into the one component that virtually all Hollywood action films shy away from: glass. While real glass can be used in explosions and cutaway shots of gunfire blasts, it can’t be used around the performers themselves, due to the danger factors involved. Instead, when a character must jump through a windowpane, candy glass is used in place of the real thing.

The finale in Chan’s most riveting effort uses a specially designed type of glass that lies somewhere in the middle, and what better place to have lots of it than in a department store. The most evident use comes when Chan is pushed headfirst into a glass shelf. With a close-up shot, the glass breaks in elongated shards that stem from the point of impact, that being from his face! If this had been candy glass, it would have shattered as if a high-speed bullet had hit it. As for his stuntmen, Chan kicks, flips, knocks, and throws them into large window displays that shatter with blistering realism. The film was nicknamed “Glass Story” for this very reason.

This is Chan’s best use of the environment around him, his only helping hand in taking care of Koo’s henchmen. Chan spins around on a clothes rack to maneuver around his attacker’s blows, he throws a mannequin in the air to divert attention, and he even uses the slick floor to slide at an oncomer. In a sporting goods store, a baseball bat and a motorcycle are brought into the scene to add even more diversity. Fong Hak-on (dressed in a white jacket) takes perhaps one of the most unbelievable forms of punishment when Chan kicks him to a back flip, sending him sliding down an escalator face first. Ouch! Kung fu is traded in for more of a brawling style, but the rhythm and timing of the fight more than make up for the lack of formalized technique. In one amazing shot Chan leaps into the air, executing a spinning round heel kick to the head, then brings it low, using the momentum to sweep another combatant’s legs.

Editor Cheung Yiu-tsung pulls off his best work yet, having built a name for himself in the field with his work on the films of Bruce Lee, Sammo Hung, and especially Chan—he has edited more than ten of his films. Most of the scene is undercranked slightly, with plenty of slow-motion shots that play up the shards of glass falling around the victims. This end fight scene was such a classic that the makers of Brandon Lee’s Rapid Fire (1992) used some of its best gags almost shot for shot in that film’s climax.

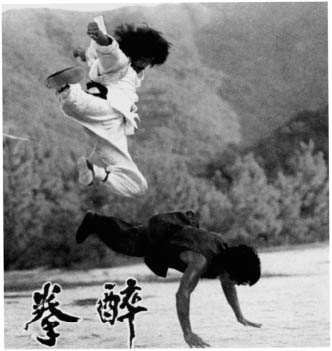

5. Drunken Master II (1994): Jackie Chan vs. Kenneth Low Houi-kang 2.35:1

No one thought that Jackie Chan honestly had it in him to put another fight like this together. It took approximately four months to shoot this exhaustive encounter, a nearly fifteen-minute finale in which Chan goes head to head—or rather foot to head—with his real-life bodyguard, Kenneth Low. Chan was supposed to have fought Korean Ho Sung-park, but their fight had to be cut short because of Ho’s lack of rhythm. Kicking has been the razzle and dazzle element of martial arts films for many years, earning men like Hwang Jang-lee and Tan Taoliang instant star status. Though many of Low’s kicks aren’t executed for power, he throws so many of them at the bewildered Chan that he barely has time to put his foot on the ground. When Low calmly puts his foot straight up into the air while taking off his glasses, the audience can see that Chan is going to have a difficult time dealing with this former champion kick-boxer.

Police Story. (Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

While no particular style of martial arts is used on Low’s end, Chan uses a freestyle kung fu form combining elements from the Northern and Southern schools called Bak Sing Choy Li Fut, which has a fluid base of motion stemming from the hips and shoulders, allowing the proponent to throw long arm and shorter hand movements. Borrowing ideas set forth in earlier bouts in the film, Chan also incorporates some breakdancing moves. These moves, furthermore, were lifted from Lau Kar-leung’s Operation Scorpio (1990), where Chin Kar-lok had to mimic an eel in order to win against the villainous fighter, who mimics a scorpion.

Chan even reprises some of his original Eight Drunken Fairy training from the first Drunken Master. Though Chan never used the Holding the Jar technique from Drunken Master in his duel with Hwang Jang-lee, he does use it several times in the sequel. Standing in the horse stance, the combatant holds out his arms slightly bent, using the hips and shoulders to generate power to send Low flailing away. The drunken style is versatile in the sense that it can be mixed with other forms, and this particular Holding the Jar movement would be something that a drunken tai chi would incorporate. Chan even dips back into the Drunken Master cookie jar when his face lights up to the drunken technique of fighting like a girl dubbed “Miss Ho.”

Drunken Master II.

The fight, however, owes a lot more to Young Master than it does to Drunken Master. In Drunken Master II Chan must drink industrial-strength alcohol, which gives him all the strength that spinach gave Popeye after a kick sends him into a bed of hot coals. Though he wore protective gloves (very noticeable in the sequence), the 500-degree hot seat did burn Chan’s arms, legs, and rear end—though he was paid an extra $250,000 for his troubles. Originally, Chan wasn’t supposed to drink at the film’s end because director Lau Kar-leung wanted to stick with the drunken style and because it clashed with Chan’s good guy persona. “Many years ago [referring to the first Drunken Master] I drink, fight; drink, fight; drink, fight! Now I have to have more education for the children. Don’t fight and don’t drink! It’s wrong. ‘Okay,’ everyone says, ‘You have to drink—it’s comedy!’ ” exclaimed Chan in a recent interview. Chan only drinks twice in the film, and both times it’s done with comic effect. As in Young Master, he displays his newfound power by putting his fists through some wooden shelves. When Low starts lashing his kicks at Chan, like in the encounter with Whang, Chan grabs Low to prevent his kicks from connecting.

The major difference between the two films is in filmmaking style, where Chan now speeds things up with crafty editing instead of leaving everything in wide-angle shots. The quality of this scene has made it one of the most welcome crowd-pleasers in the recent past.

6. Mr. Canton and Lady Rose (1989): Jackie Chan vs. Mobsters 2.35:1

If a Chan fight scene could ever be accused of being too choreographed, this is probably the scene they would be talking about. Yet the inventiveness and complexity of this scene is something to behold, seeing how Chan spent only one month in setting it up. It takes place inside of a gangster’s headquarters, complete with fans, a spiral staircase, and plenty of chairs, tables, and revolving doors. Chan makes expert use of widescreen, with glorious action on all sides. Since the film takes place in the thirties, Chan is dressed similar to Buster Keaton, and the latter would have probably been Chan’s biggest fan if he had lived to see it.

The colorfully lavish set inspires Chan’s inventive choreography. In one shot a man on the other side of a table throws a chair at him, while Chan kicks his chair under it, sweeping the man’s feet. In another shot, Chan kicks a pot up into the air, punches a guy in front of him, and as the pot comes back down, he punches it toward a foe behind him. A slide down a spiral banister is cut short when Chan sticks his leg up between the balusters to trip a guy coming down. He also plays a little game of musical chairs that the other guys have a hard time learning! This is Chan’s best dance number, and its startling complexities become more impressive with each viewing.

Chan’s best use of environment: Mr. Canton and Lady Rose. (By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

7. Dragons Forever (1988): Jackie Chan vs. Benny “the Jet” Urquidez 1.85:1

The final fight in this film is again one of Sammo Hung’s better action montages. He uses wires, elaborate overhead shots and powder to accent the blows, and the humor is more subtle than in Wheels on Meals.

After Yuen Biao and Jackie Chan pretty much knock out the competition, Chan is left to face Benny a second time. Since the production was rushed, the fight was shot over the course of twenty-four hours, but haste doesn’t show. Once again the bout is broken up into different segments, allowing for Yuen Wah’s wiry characterization to intervene at some very inopportune moments.

Chan and Urquidez are once again ready to do combat, but this time they are dressed in long sleeves, buttoned-up shirts, and ties. Before the two commence fighting, they stare each other down, raise their guards, and loosen their ties. As the fight continues, they pull off their ties in synch, and Chan even loosens up his cuff links and takes his shirt off. All of the more comical facial expressions of Wheels on Meals are traded in for serious looks. When Chan gets popped in the nose, a steady stream of blood pours out, which he wipes off on his shirt. Chan and Urquidez roll with a whole new battery of punches, kicks, elbows, and knees. Instead of an empty room, the warehouse set allows them to fight all around its assorted obstacles.

Dragons Forever. (Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

The entire scene is filled with the high energy that one might expect, but there is one great technique-driven sequence that stays realistic while being humorous at the same time. When the two begin trading heavy punches, they only connect with one another’s forearms. After each man throws a half-dozen punches, they stop, look at each other, and begin to shake it off. The two were actually hitting nerves that run along either side of the arm from the elbow to the wrist (radial and median). A heavy blow to either nerve can render an arm useless for a few seconds. By the looks of the sequence, they were both supposedly hitting these nerves.

The fight ends with a beautifully executed move where Urquidez, on Chan’s right side, with both of them facing forward, is powerfully kicked by Chan’s left leg! One final note on this fight scene doesn’t involve Chan, but instead Yuen Wah. When Hung injects Yuen with a needle to slow him down, Yuen makes his hands into claws as he strikes a pose, only to wither down to the ground when the drug takes effect. Though Yuen was one of Chan’s Peking Opera brothers, he prided himself on having learned Ying Jow Pai, otherwise known as Eagle Claw. Hung was definitely making a comical reference to this style.

Chan and Benny Lai, Police Story II. (Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

All of the action in this sequence is topnotch, and it has made Dragons Forever one of the most classic fight films of the eighties.

8. Police Story II (1988): Jackie Chan vs. Benny Lai 2.35:1

Chan has no problem defeating Koo’s men for a second time or the mad bombers during numerous skirmishes. When you watch him in action, it’s almost as if a little bit of Steven Seagal’s or Bruce Lee’s no-nonsense tough guys had rubbed off on him. In Chan’s world, however, he can never truly be shown as the best fighter, especially when he tries to take on stuntman-friend Benny Lai in the film’s final moments.

During the middle of Police Story II, when Chan and one of his cohorts discover the bomber’s lair and Lai’s deaf character for the first time, they show sympathy for him in the way they try to communicate that he’s under arrest. They completely lose any thought that a deaf person could pose any threat to either one of them. Within a few seconds, though, Lai jumps off the side of the wall, has both of them down, and is able to make his escape without any conflict.

After disposing of the gang’s other two members inside of a fireworks warehouse, Chan is once again confronted with Lai, who demonstrates his abilities by jumping up into the air and kicking him three times all in one shot! While Chan is unsuccessfully trying to fight him, the camera keeps cutting to his astonished face as he tries to wipe the sweat off his brow. Not one time during this entire matchup does Chan even land one punch or kick. He tries to fake Lai out by climbing on the underside of some steps, displaying an incredible show of strength, but Lai is waiting at every turn. Chan finally tries to escape his clutches, but when he comes upon a crate full of small firecrackers, Chan decides to give Lai a piece of his own medicine. While Lai can’t actually talk in the film, he makes these bizarre, little animal sounds. Chan mimics him when he gets the upper hand, pelting him with the flame-inducing firecrackers.

No American star would ever let such a beating take place without physically coming back at the end. Chan’s ironic finale puts a dampening effect on the pretentious behavior his character had exhibited during the course of the film.

9. Drunken Master (1979): Jackie Chan vs. Hwang Jang-lee 2.35:1

Chan’s second fight with Korean boot-kicker Hwang Jang-lee is a classic test between the Eight Drunken Fairies and the traditional use of tae kwon do. Chan uses all eight techniques learned from his “drunken” teacher, played by Simon Yuen. The stance for the drunken style has the participant outstretch his arms and curl the fingers toward the body as if holding a cup (of alcohol). By doing so, the ball of the wrist is exposed, allowing the user to unleash what is commonly called an ox strike or crane technique. This move is used only in close encounters.

Hwang Jang-lee in action with Chan. Drunken Master. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

(By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Honorable Mention goes to Armour of God’s fight with the monks, Drunken Master II’s duel with Lau Kar-leung under a train, Project A II’s fight with Chan Wei-man and Wang Lung-wei, and finally Dragons Forever’s three-way battle between Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, and Yuen Biao.

As for Hwang, he sticks to more of the traditional tae kwon do, which means the art of kicking and punching. Tae kwon do has become watered down in the States, having been made popular by competition. When the art was first developed, it was more of a complete system utilizing open hand movements, wrist locks, and throws. And Hwang Jang-lee was a definite traditionalist, learning from within the origins of the art. He uses an open hand almost the entire time in this bout with Chan and performs some of his trademark high-kicking techniques. If Americans think that Jean-Claude Van Damme is a great kicker, one look at Hwang Jang-lee’s abilities will surely make anyone forget about the Muscles from Brussels! Hwang’s amazing footwork was so popular that he was invited to make a documentary called The Art of High Impact Kicking during the early eighties.

The fifteen-minute battle in Drunken Master is one of director Yuen Woo-ping’s most famous fight sequences, and Chan’s handling of the drunken style is both comical and seemingly useful.

10. Police Story II (1988): Jackie Chan vs. Koo’s henchmen on the playground 2.35:1

It was just a walk in the park for Chan, as he and Maggie Cheung were trying to work out their differences as a couple. Koo’s right-hand man had different plans for him, however, when he lures him onto a playground. A fight ensues, pitting Chan against his stuntmen in a grueling session of pain as they battle it out around a swing set, a slide, and other playground objects. What makes this fight more stunning than the rest of his ensemble matches is his stuntmen. Usually, Chan stands out as being a scene’s only combatant to use unconventional fighting skills to overcome his opponents, but this fight has everyone flipping, jumping, and orchestrating their bodies. It’s hard to keep your eyes just on Chan as many of his stuntmen are performing some of the better flips and flops. Like all of the fight sequences in Police Story II, they are overly sped up for some reason, but this doesn’t detract from the audience’s excitement in watching these truly gifted individuals duke it out with fists, feet, and metal rods, which seem to come out of nowhere. In one shot Chan runs up the side of a swing set, slapping his stick on the top of one of his stuntman’s heads.

When Chan is almost crushed by the enemy car that corners him in an alley, the music really picks up to show that Chan is going to turn things around. In one of his fight’s more comical moments, he tries to pick up a drainage pipe; the menacing scowl on his face is suddenly reduced to a look of embarrassment when he can’t even budge it.

Sadly, Police Story II has never been released in a complete letterbox on videotape in any language. (There is a Japanese laser disc, but no other.) This fight as well as all of the other action scenes are left to suffer.