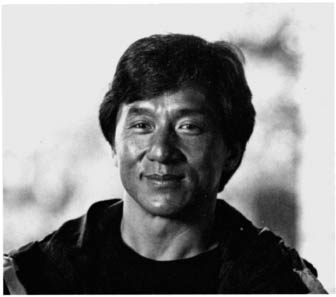

Chan after a hard day’s work on Mr. Nice Guy (1997). (Courtesy Golden Harvest)

During Jackie Chan’s first tour of duty in America, in 1980 with The Big Brawl, audiences had no other choice but to compare him to Bruce Lee. Lee brought a fierce realism to fighting that the audience could easily identify. Because Chan was Chinese, he was immediately labeled a kung fu fighter, but when his comic approach started to show through, it created too much of a contradiction to Lee’s. Chan was also young, only twenty-five, and his abilities as a director and a performer had not yet matured to the level that they would only six years later with Police Story. No one had the chance to see Chan’s trademark use of props or dizzying fight sequences, so Bruce Lee was their only vantage point. While he became a household name all over the world, Jackie Chan had lost the American market, where he was considered a failed martial arts star.

But while Chan remained an unknown to the American mainstream, videophiles embraced him. It all started in 1985 when Ric Meyers wrote the book From Bruce Lee to Ninjas: Martial Arts Movies. Sure, martial arts magazines like Martial Arts Movies had introduced Chan to that audience as early as 1980, but that was irrelevant. The book had a few problems (confusing Yuen Kwai as Yuen Woo-ping’s brother and misidentifying a half-page picture showing Lee strangling Chan in Enter the Dragon) and only covered Chan’s films up to Project A, but Meyer’s book was one of the first in English to accurately portray Chan and his art. Meyers also helmed Martial Arts Movies Associates, a fanzine in which he discussed Chan in great detail.

Yet it wasn’t until late 1988 that Meyers really got the word out. A British television series called “The Incredibly Strange Film Show” was churning out programs about the underbelly of cinema. Horror maestros like Hershall Gordon Lewis and George Romero would have their own shows, as did Mexican horror wrestling movies and early sexploitation flicks from the late fifties and early sixties. A disgruntled female employee of the show wanted to bring someone in who had more of an even taste, and Ric Meyers was her man. After a brief meeting, Meyers convinced Jonathan Ross (host of the show) and his crew to take a look at the Asian invasion, which included Godzilla, Japanese animation films, and Chinese kung fu films. Meyers quickly assembled a five-videotape tutorial on the pioneers of this invasion. After Ross’s examination, Jackie Chan and New Wave director Tsui Hark were to have separate programs.

At the time Chan was in the middle of filming Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, and Ross and his crew were able to go to Hong Kong to meet with him. Golden Harvest also helped by supplying action footage from some of Chan’s best films: Winners & Sinners, Armour of God, Police Story II, and Project A. An offshoot of the original program, “Son of the Incredibly Strange Film Show” aired an hour-long segment on Chan, and the show eventually played in America. Unsuspecting viewers had no choice but to be drawn into Chan’s world. The segment was the first to show Chan’s devastating injury from his tree fall in Armour of God, and when viewers saw that he just went right back to shooting only a month later, they were hooked. Never before had they seen someone who was willing to go to those lengths to entertain the audience.

When the same people who had marveled over Chuck Norris and Bruce Lee began searching for Chan’s films, the bootleggers came out of the woodwork. They discovered that Hong Kong films were already subtitled in English because of Britain’s rule at the time, saving them some labor. Video bootleggers aren’t exactly the brains behind creating fandom—they just feed it. “The bootleggers wouldn’t have known that these movies existed if I hadn’t started getting them from Hong Kong and disseminating them amongst my buddies in the comic industry, the book industry, the television industry, and the movie industry,” said Meyers. Anyone who prides him- or herself as a film connoisseur will have to look further than the local video store—just as a wine connoisseur doesn’t build a collection from the supermarket. By looking in the backs of genre magazines like Starlog and Fangoria, this new elect could find ads for Hong Kong films and Jackie Chan.

Hong Kong cinema fans like Tony Rayns, Tod Booth, and David Chute also began to write frequently about Chan’s films since they played in local Chinese venues in New York, San Francisco, and elsewhere. It’s amazing to think that all of Jackie Chan’s films have played in the United States since Drunken Master (1978), and no one but the Chinese-Americans had known about it. In 1990 someone at Miramax, one of the few successful independent film companies, did know about it. At that point, Miramax offered Chan the opportunity to make a splash in America for a second time, but it meant splicing Police Story and its sequel into one film. Thankfully, Chan declined Miramax’s proposed edit.

With the multitude of videotapes that began to float around, coupled with various film magazine articles and an official video release of Chan’s Police Story under the name Police Force, people were finally starting to take notice of what he was all about. To capitalize on the revitalized interest in Hong Kong cinema and Jackie Chan, two Golden Harvest representatives, Tom Gray and Roberta Chow (Raymond Chow’s daughter), set RIM Film Distributors in motion. Though its parent company was Golden Harvest, RIM began an intense marketing campaign to put Hong Kong films in major American theaters under the banner “Festival Hong Kong,” with Jackie Chan as the headliner. While the festival approach seemed to work in most major cities, RIM tried to branch out too quickly without needed marketing support. Some cities would put on these festivals without previewing the films for critics or offering literature to explain what they would be seeing. After two weeks, with no media coverage, the films would vanish.

With showings like this, RIM opted to move to something more conventional: Jackie Chan Film Festivals. Soon New York, California, and Chicago were bombarded with Chan’s action films, and it seemed impossible for anyone to miss out on the opportunity to see him. Golden Harvest, nervous about saturating the American market with their biggest moneymaker before his newer films came out, removed his films from circulation and disbanded RIM, leaving Roberta Chow to head up a small branch of Golden Harvest in Los Angeles. In 1994, Media Asia was founded to handle international distribution of all Golden Harvest’s titles, including those of Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan (although they would begin producing their own films as well in competition with Golden Harvest). Golden Harvest was waiting for the right moment to cash in on their biggest star—that moment would be when all of America could see Chan at once.

(As a consequence, only Seasonal’s Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow and Drunken Master could be acquired for showings, and even then in limited distribution. America’s Chinatown movie theaters have suffered since they could no longer show their biggest draw. Only a handful of Chinatown theaters exist in America now.)

In the meantime, Hong Kong film fandom spread like wildfire. Mavens of the cinema created fanzines to meet the growing interest. Soon publications like Oriental Cinema, Asian Trash Cinema, and Hong Kong Film Connection took over to educate greenhorns in America about Chan and his fellow film pioneers. All of a sudden, Chinese video stores had to start selling and renting to the untapped non-Asian market, which managed to support many of these stores even though the new films generally weren’t that good. Ironically, the only films that were not subtitled in English were from Jackie Chan. However, Taiwan, whose third spoken language is English, had subtitled versions dubbed in Mandarin for rent in Mandarin Chinese video stores. The major distribution companies, like Tai Seng and World Video, had to start greeting the phones in English since many of the callers would be ambitious American video store owners.

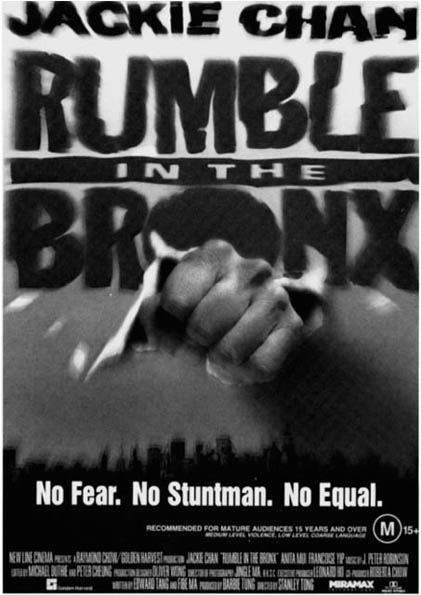

It was becoming apparent that Jackie Chan would eventually claim the market he thought he would never have, and Stanley Tong was just the man to do it. During RIM’s more successful days in operation, the most popular Jackie Chan film among casual viewers—not diehard Hong Kong film fans—was Police Story III: Supercop. The film was so popular that RIM even cut together its own trailer to show alongside American film trailers. In 1993, Supercop was being shown in limited release three years before Miramax re-released it. It was only natural that Stanley Tong’s Rumble in the Bronx would be Jackie Chan’s return to America. “Like all of Jackie’s films, Rumble was made with the Asian market in mind, but we hoped that the North American setting would help the American market. What we didn’t know was that it was going to be a big hit,” stated Roberta Chow, Rumble’s producer.

New Line Cinema picked up Rumble for distribution for $5 million dollars, and after thirteen minutes were excised from the running time (mostly Chinese dialogue sequences) and the film was dubbed, it was released in early 1996. Avid Hong Kong film fans may have panned it during its original release in Hong Kong and select American Chinese theaters in 1994, citing a lack of plot, but to American audiences the plotless action film was what movies were all about. Rumble took in $9.8 million its opening weekend (the number-one film that weekend) and topped out at over $30 million by the time the dust had settled.

With a fantastic trailer and a rigorous marketing campaign, Chan was able to secure spots on David Letterman’s and Jay Leno’s TV shows, but the most surprising coup was the Lifetime Achievement Award given to him at the 1995 MTV Movie Awards. Pop culture icon Quentin Tarantino presented the award, though it was doubtful that MTV really knew who Jackie Chan was, since these awards are given out almost as a joke: the following year MTV gave out the same award to Godzilla! Composed of Generation Xers, the crowd listened as their god delivered the award along with a few words of encouragement. “He is one of the best filmmakers the world has ever known! He is one of the great physical comedians since sound came into film. If I could be any actor, I would have the life Jackie Chan has,” said Tarantino. The crowd went crazy with this proclamation, and even the people who thought Jackie Chan was a fad had to reevaluate their own feelings for the man.

It’s important to note that Hollywood circles are still restrictive when it comes to anything and anybody that doesn’t represent White America. The current state of cinema has left minorities to wander aimlessly through television channels rather than the big screen. Only a select few have been able to rise above the stereotypes to get star roles. During the seventies, when Bruce Lee and Sonny Chiba were becoming popular amid the martial arts film explosion, African-Americans were carving a niche with blaxploitation films. Later they even combined the two genres, launching Jim Kelly, Ron Van Cleef, and others in rip-off films like Black Belt Jones and The Black Dragon.

Latino actors have also generally been in a rut, but Asian actors, particularly, have had to work within stereotypes and have been kept from being anything more. Only films with Asian themes have presented them with opportunities to play more than Chinese food takeout drivers or gang members who know martial arts. Films like The Last Emperor (1987) are far and few between. If anything could have been the cause for such stereotypes, it was the exploitation genres and kung fu films that left a bad taste in the mouths of mainstream America with their atrocious dubbing and weak production values. Bruce Lee was different because he was known in America before his Hong Kong film days, due to The Green Hornet television series, among others, during the sixties.

Jackie Chan still had to fight this system even during the so-called politically correct nineties. For example, hours of photography were shot for the Rumble in the Bronx poster, yet a large fist was the only thing to make it on the original one sheet. Though Jackie Chan’s name is printed in big letters across the top of the poster, all of the credits with Chinese names listed below are darkened to the point that one would have to be looking only inches away from the poster to be able to make them out. In the Americanization of Chan, his Hong Kong origins and ties would be downplayed. The film’s dubbing made things even worse, but Chan at least looped his own voice.

The most surprising aspect of Rumble in the Bronx was its “R” rating. All of the violence was kept on a cartoonish level, and aside from a brief mooning, there wasn’t any nudity in the film. Jackie Chan, Willie Chan, and Roberta Chow even went to the ratings board, pleading to have the rating changed to “PG-13.” No go. The official reason for the “R” rating was the word fuck used in a sexual connotation, though it’s doubtful that one would ever be able to hear this. “I think they [New Line] made some very judicious cuts,” said Chow. Chan has always said that his films are family entertainment, and this was a slap in the face. Compared to most Hollywood films, an “R” rating for Rumble seems laughable.

Even with such problems, everyone knew who Jackie Chan was and what he was about. That was the point. New Line Cinema can be commended for pulling off one of the great marketing campaigns. A junket in several key cities also marked the film’s opening—although the New Line representative who accompanied Chan had never seen one of his films aside from Rumble! As a direct result of this marketing campaign, the film’s popularity continued on video store shelves.

Miramax picked up Supercop in a similar attempt to cash in on Chan’s new U.S. popularity. By not doing their homework, though, Miramax released a film that was four years old in a market that had seen it countless times due to RIM’s push two years earlier. Unlike Rumble in the Bronx, English-dubbed videocassettes of Supercop had previously been made available by those same ambitious video store owners. The film would have done marginal business had it been released in August during its original time slot, but Miramax made the foolish mistake of putting it out in July. And what was so special about July—aside from the normal, big-budget Hollywood fare?

Carrying over from Rumble in the Bronx, Supercop still did tout Chan as the real thing who does all of his own stunts. Can you get any more real than the Olympics, going on at the same time? Supercop ended up making half of what Rumble did, and the dubbing actually called Chan “the Supercop,” whereas the original makes mention of the subtitle only once (a scene ironically cut from the American version)! Chan and Michelle Yeoh did do their own dubbing for the film, which helped, but the soundtrack added vulgar raps and, even more idiotically, a redo of Carl Douglas’s 1974 disco hit “Kung Fu Fighting.”

While Supercop’s marketing campaign virtually fell apart after the film didn’t fare well at the box office, Chan still appeared in television spots. Entertainment Tonight did an on-set visit, and GQ interviewed him during the shooting of his most recent effort, Mr. Nice Guy. Chan appeared again on David Letterman and Jay Leno.

But on this tour Michelle Yeoh would get in on the action as well. Managed by Terence Chang, manager of John Woo, Yeoh secured numerous television spots, such as with Conan O’Brien, Rosie O’Donnell, and Entertainment Tonight. Yeoh has a better understanding of English than Chan, and America had an easier time accepting her. In a politically correct society, who says that a woman can’t be an action star? Women embraced Yeoh, and Rosie O’Donnell’s talk show was the perfect move. Yeoh mentioned that Chan didn’t want her to perform the motorcycle stunt in Supercop, citing his belief that women shouldn’t do action. Before the boos from the crowd could begin, Chan appeared. Originally, he was supposed to break a chair, but he let O’Donnell crash it over him instead—as if in repentance for his women and action comment. In any case, as a result of Supercop, Michelle Yeoh secured a Bond girl role in Tomorrow Never Dies, with Pierce Brosnan as 007.

Rumors flew in Hong Kong and Hollywood circles that Chan was emphatic about appearing alone on the public relations tour. Only a few autograph signings allowed Chan and Yeoh to be seen together. Both Michelle Yeoh and Stanley Tong had to find other means of earning the spotlight. Chan was also quoted on many occasions that he in fact directed a lot of Rumble and Supercop, which led to another rumor: that Chan and Tong would never work together again. The actuality is that Chan and Tong still discuss future projects, but Tong’s success as an American filmmaker will have to take precedence.

New Line picked up First Strike (retitled Jackie Chan’s First Strike), and it opened in America in January 1997. Jackie Chan’s First Strike received more extensive cuts in its American release version—some twenty minutes—than did Supercop and Rumble in the Bronx in theirs. The first action scene comes along in ten minutes instead of twenty in the original version. The biggest cuts came in the underwater fight finale, where ten minutes of footage was trimmed, including the shots of the fake shark with feet hanging out his mouth. With other graphic violence cut from the film (characters killed by machine gun fire), Jackie Chan’s First Strike was given a PG-13 rating, which helped introduce Chan to children. The English dubbing doesn’t hurt the film too much (despite the fact that “Tsui” is pronounced every which way rather than the correct way: “Choy”), and Chan did his own dubbing again. Critical response was generally favorable. All in all, the American redo is a more satisfying film with its sped-up pace.

As Jackie Chan continued to establish his presence in America, the question arose over which—Hong Kong or Hollywood?—would be the bigger part of Chan’s film future. One stirring rumor created a much publicized breakup between Jackie and Willie that never occurred. In theory, Willie Chan represents a part of Jackie Chan’s persona—that part being the business side. Without Willie Chan, Jackie Chan would not be where he is today. As the story goes, an American agency went directly to Jackie to express interest in representing him in the States. When Jackie reciprocated the interest, word got back to Willie, putting a strain on the relationship. It sounds like a soap opera, but it’s entirely not true. Willie Chan set up meetings for Jackie Chan to get American representation, since Willie doesn’t understand the way Hollywood works.

After much deliberation, Chan signed with the William Morris Agency, which represents many of Hollywood’s top stars. They now represent Chan in the United States and the rest of the world except Hong Kong and South East Asia. When asked about this other representation, Willie Chan responded: “When you’ve worked with a guy for more than twenty years, the ‘title’ becomes rather unimportant! I only want the best for him. Suffice it to say, we are still working together.” Willie Chan will always be managing director of Jackie & Willie Productions, and the two will continue to have a long, prosperous business future together.

Chan has had some recent shots at Hollywood film roles, but they weren’t exactly what he was looking for. Chan was supposed to have starred alongside Michael Douglas in Black Rain (1988), alongside Sylvester Stallone in the never-made Rambo IV, and as the villain in Demolition Man, played by Wesley Snipes. Confucius Brown was to be a buddy picture pairing Chan and Wesley Snipes, but Snipes was booked through 1998. An advance marketing slide in some film theaters announced Chan starring with Chris Farley for Hollywood Ninja, but an overexcited Columbia Pictures employee must have jumped the gun, since Farley is really teamed up with Robin Shou, star of Mortal Kombat. As for reality, Chan said it best when he stated, “The only way you can be sure that I am connected with a movie is when it actually comes out.”

Bringing his career full circle—after bouts with Stanley Tong and a host of other directors, a reteaming with Sammo Hung, and countless offers from Hollywood—Chan is back directing again. His next film, set to shoot in Africa, is another action adventure story, this time using the French Foreign Legion and Chan as a mercenary. Initially entitled Safari, it’s now called Who Am I? Before Chan even finished with location scouting, the William Morris Agency announced other plans for Chan.

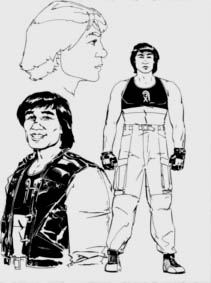

Critic Ric Meyers’s relationships with Jackie Chan and with Hong Kong films have also come full circle. After penning the 1988 novel The Shibo Discipline, in which Chan is a featured character, Meyers wrote the first-ever Jackie Chan comic book, entitled Spartan X. “I saw the first Chan film as a comic book come to life. He’s a living comic book—so let’s do a comic book! This was way before Rumble in the Bronx was released.” Spartan X’s title is based on the alternative title of Wheels on Meals, but the comic book character is from Armour of God. The comic book stories are a continuation of Asian Hawk’s adventures. The Armour of God films are the only Jackie Chan-directed pictures to really stray from the underdog mold. Asian Hawk’s conflicts arise out of his quests, and his character has money to burn on fancy gadgets and expensive vehicles. The Japanese have subtitled Chan’s films the way they see fit, with no bearing on what the films are actually about. Dragons Forever is known as Cyclone Z, Crime Story is The New Police Story, and Wheels on Meals is Spartan X. Meyers liked the Japanese title for Wheels on Meals and felt that the title represents Jackie Chan the perfect comic book way. As Meyers explains, “I could actually explain why he was called Spartan X—‘Spartan,’ because he comes with empty hands—he isn’t carrying a gun and doesn’t like them. As for ‘X,’ it represents the unknown, and it’s a big letter in comic books.”

Model sheet for Spartan X. (Courtesy of Topps. © 1997 Jackie & Willie Productions, Ltd. Published exclusively by The Topps Company)

The six-issue series, titled “The Armour of Heaven,” will be released May 1997, with a graphic novel to follow that summer. Meyers actually ran the ideas by Jackie himself, but Chan didn’t have anything to do with the actual storyline. Meyers also contributed to an A & E Biography TV special on Jackie Chan, which also appeared on the Discovery Channel on American cable.

(Courtesy of Topps. © 1997 Jackie & Willie Productions, Ltd. Published exclusively by The Topps Company)

Chan has a cameo with Sylvester Stallone and other Hollywood heavies in the upcoming project known as An Alan Smithee Film, set in the world of Robert Altman’s The Player. In The Hollywood Reporter, Chan made the front page with a proposed film, Rush Hour, pairing him up with comedian Martin Lawrence. Within a couple of weeks of this news, Chan made a cameo appearance on Martin, Lawrence’s trendy television sitcom. Rush Hour will be about a Chinese security officer and an FBI agent embroiled in a kidnapping during one of the worst traffic jams in Los Angeles history. Lawrence has yet to prove himself on the big screen having failed at the box office with The Thin Line Between Love and Hate. He seems better suited for supporting film roles, but Martin does have a loyal following.

After the Rush Hour news, Chan’s name was taken off as director of Who Am I? But Rush Hour was soon in limbo: Lawrence was slapped with sexual harassment charges by a former costar. Although originally scheduled for shooting in February 1997, Rush Hour may never get made since Chan cannot allow his good-guy image to be tarnished. All of a sudden, Chan was listed again as director of Who Am I?, which is set to shoot in mid-1997.

The real Mr. Nice Guy. (Courtesy of Golden Harvest).

Jackie rides again in Mr. Nice Guy. (Courtesy of Golden Harvest).

Whether or not Chan re-creates Hong Kong-style action sequences in America is now a side issue. The big news is that he is here to stay.

Jackie Chan has conquered the final frontier of America by doing what he does best. It’s unlikely that he will ever make the American movie that so many people want him to make. Did Buster Keaton do well when MGM made him do what they wanted him to do? Besides, the action in Jackie Chan’s films is not set down in postproduction with special effects, so if Jackie’s real action is what makes him popular, an American film will never do him justice. They will never believe or accept the fact that Chan spends a month or longer shooting every action sequence.

To put everything in perspective, Chan said, “If I get a Steven Spielberg or James Cameron movie, I do it for free! Honestly. For Stallone? I take only half salary—half million, 1 million dollars, it’s OK. But if some company just wants me because I’m hot, then I want 22 million dollars American! No kidding!” While this could have been a maneuver to keep American film companies out to make a quick buck away from him, Chan has made the point that he will never fall back into the Protector-like situation. He is above servitude to any director who just goes through the motions.

Mr. Nice Guy is Chan’s first step toward reaching mainstream America—which doesn’t understand dubbing or care about Chinese culture. Thus, English is used 95% of the time in this film. In fact, New Line representatives and an American voice coach were on the set of Mr. Nice Guy to ensure a smooth-sounding English dialogue. In a further instance of Americanization, most of the film’s postproduction was done in Los Angeles. Without the headaches—and lackluster results—of dubbing, and with more action to showcase Chan’s abilities, Mr. Nice Guy is sure to be a hit. Mr. Nice Guy headlined the last Chinese New Year 1997 before the Mainland takeover on July 1, 1997. It is a nonstop chase sequence that allows Chan to pay homage to his eighties’ flicks by working them into the narrative.

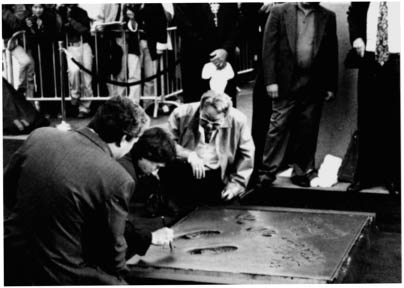

“My dream come true!” (Courtesy of Joy C. Al-Sofi, President, Jackie Chan Fan Club USA)

With the popularity of Rumble in the Bronx and Supercop, Miramax plans on releasing Armour of God II and Drunken Master II in American theaters. A January release date hurt Jackie Chan’s First Strike, which did only fair business. Unfortunately, the same thing that helped Chan secure his position in America, however, led to lesser box office numbers for First Strike. Along with Thunderbolt, it can easily be found on laser disc in Chinese video stores. They both are in full letterbox, boast great subtitles, and are shown with stereo audio tracks. Since they have been released in Hong Kong, many video stores just order them direct, since distributors like Tai Seng can’t carry them.

If New Line really wants Chan to do well in America, it will start releasing his films at the same time they are released in Asia. Only then will everyone witness Chan’s marvels at the same time. Unfortunately, New Line doesn’t feel this way, and it has to do its own tweaking to market him its way.

Videocassettes have been pouring in from different companies, trying to cash in on Chan’s popularity by slapping his modern face on box covers of older films. The Japanese market has even released two box sets, each having four of Chan’s films in letterbox.

The tangible sign of Chan’s conquest of America: his foot and hand prints at Grauman’s Chinese Theater, Los Angeles, January 5, 1997. (Courtesy of Joy C. Al-Sofi, President, Jackie Chan Fan Club USA)

The world can’t get enough of Jackie Chan, and Jackie Chan can’t get enough of the world. He is a world-class entertainer, with a mission to please his adoring fans with something new and exciting with every picture he makes. Back in the director’s seat again, Chan seems destined to reinvent himself once more—after all, he truly knows what’s best for him. And we can be thankful for that.