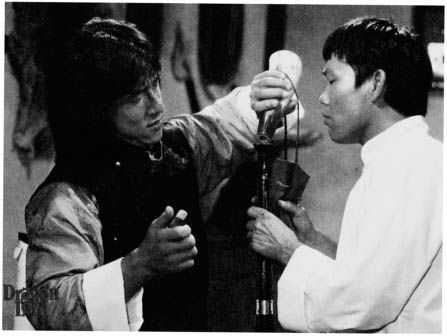

Korean hapkido master Whang Inn-sik tries to dispose of Jackie Chan in the finale of Dragon Lord. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Chan had actually started much of his film career with Golden Harvest. With Sammo Hung’s help, Chan secured small roles not only in the Bruce Lee films but Hand of Death and several of the Huang Feng efforts that Hung was action directing. In 1973 Chan starred as a Japanese villain in The Heroine. In another early Golden Harvest effort, All in the Family (1975), Chan is seen embarrassingly groping a topless girl in bed.

With the market changing so rapidly in the late seventies, Raymond Chow was banking on Jackie Chan. After Bruce Lee, Chow’s only claim to fame had been launching Angela Mao as the female version of Lee, and her high-kicking abilities made her an instant success internationally. Like Ng See-yuen, Chow knew how the system worked and knew that Chan would make a worthy replacement for Bruce Lee in terms of box office—even if Chan’s style was different. With more control and money to work with, it was necessary for Chan to put the coup de grace on his kung fu days with Young Master (1980), his first film with Golden Harvest as a full-fledged star.

In the wake of all the Seasonal cash-in films that kept chipping away at traditional values, Chan returned to those values, but he had an agenda. He wanted to bring his own choreography talents to classical kung fu sequences, but it was also important to have a story promoting moral values like loyalty, trust, and brotherhood. Chan wanted to stay away from the revenge plots that drove most kung fu films. Lo Wei had released two of his earlier films in the midst of Chan’s Seasonal success, so Chan’s popularity was still questionable. Many critics believed that if Young Master didn’t make money, Chan’s career would be over.

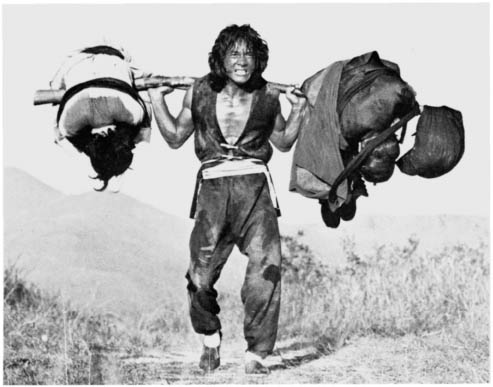

Young Master (1980). (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

In Young Master Chan once again plays a student in a kung fu school whose mission is to win a lion dance competition against a rival school. Lion dance competitions serve as a way for schools to show their expertise, and in film they were constantly used as a device to set up rival schools against one another. These are by no means friendly competitions—winning is everything. When the school’s best student, Tiger, is injured and cannot participate, Chan is picked as his replacement. Chan discovers that Tiger has betrayed the school by operating the rival’s lion. Chan loses to his former “brother,” but he keeps Tiger’s betrayal a secret. Tiger eventually leaves the school entirely for monetary gain.

Chan sets off to find his former schoolmate and bring him back to his senses. Tiger instead returns to the rival school, which uses him to rescue its imprisoned master from the local police. The master’s lackeys set up Tiger to take the blame for a robbery that follows, and Chan must come to his aid by defeating the enemy. The only problem is, Chan is mistaken for Tiger, and the Sheriff and his men go after him.

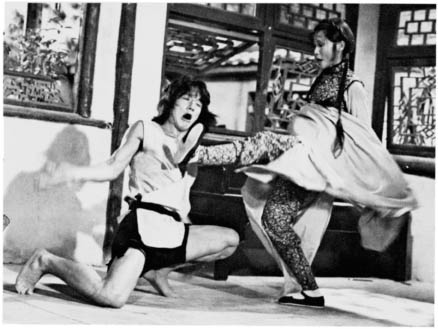

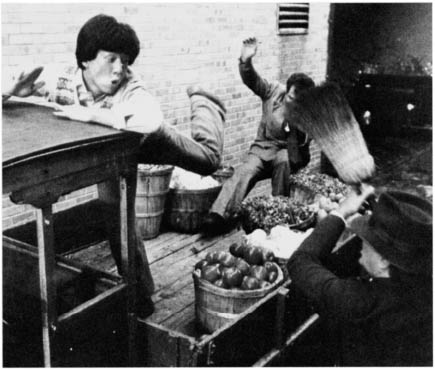

Like his character, who alone saves the day, Jackie Chan is the only one who can make the film work, since he doesn’t want the script or his costars to share the spotlight. All of the kung fu sequences are brilliantly choreographed and boast Chan’s limitless physical abilities. From the opening lion dance, which contains an amazing one-shot wonder—the rear end of the lion kicks the cabbage into Chan’s hands in the front—Young Master is full of invention. When Chan goes to the rival school to find Tiger, he must then prove himself against an obese worker, Chan wielding a fan in defense. In another great one-shot, Chan kicks the open fan straight up into the air and catches it with the greatest of ease. It took Chan over five hundred takes to get that shot just right! Chan also tosses around a broadsword, fighting off the Sheriff’s men, and even goes up against his Peking Opera brother Yuen Biao with a sawhorse, or small bench. As a final tip of his hat to the Seasonal formula, he must fight off a girl, who whips him using the skirt style of kung fu, where all of the leg movements are hidden by a large skirt. He would later bring this style into his own repertoire when he has to fight the master’s two henchmen.

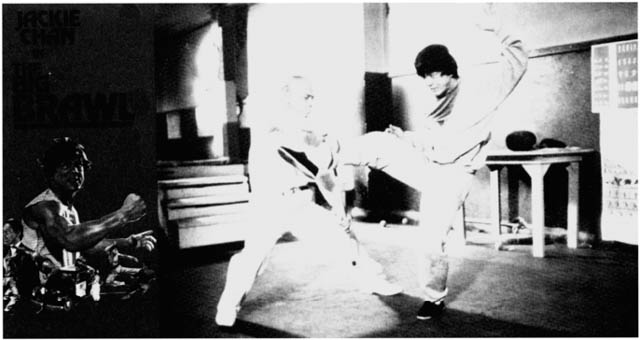

The final fight, however, has garnered the film more praise than any other scene. Chan must fight off Whang Inn-sik, a master of another Korean martial art known as hapkido. Whang started his career in 1972 when his students, Sammo Hung and Angela Mao, urged him to play the villain in Hapkido, which also starred his master, Choi Joy-san, the art’s founder. Chan worked on this film as a stunt-man and noticed him in several of the other Huang Feng-directed outings of the early seventies. Whang also played the Japanese fighter who gave Bruce Lee a run for his money in Return of the Dragon. Coincidentally, Young Master features two other Lee veterans: Tien Fong played the good school’s headmaster, as well as a similar role in The Chinese Connection, and the sheriff, Shek Kin, played the infamous Dr. Han in Enter the Dragon. When Golden Harvest gave way to using Korean fighting systems in kung fu films, tae kwon do was the dominant form.

Chan fights off the Sheriff’s men in Young Master.. . . . . then is whipped by the Sheriff’s daughter. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Chan wanted more for the end fight of Young Master. He brought in the complete system of hapkido, which not only uses the lighting-fast kicks and punches, but throws and joint locks as well for variety. In a thrilling twenty-minute duel, Chan is pummeled at every turn, whining and wincing over his inability to match Whang’s skills. Between his exhausting bouts with Whang, Chan finds a coach in the form of the rival school’s servant, who gives Chan advice, water, and a little extra breathing room.

After being kicked to the ground in what looks like a final blow, Chan immediately stands back up, forcing a puzzled look from his foe. The only way for Chan’s body to have endured such a hit is plain numbness. “I remember Chan thinking of a way to come back and win in that scene,” Whang says, “and all of the sudden, he ran across a viewing of the ‘Incredible Hulk.’ ” Finding inspiration in the Marvel Comics mean green hero, Chan becomes a raging madman, running at Whang and using no structure or direct force but sheer, raw energy as his combative form.

Chan may have saved the day, but he ended the film completely covered in bandages. Before the credits could roll, the bandaged Chan looks straight into the camera and waves bye-bye, signifying his retirement from the kung fu genre. When he broke down into a whirlwind of energy at the end of the film, cashing in his disciplined technique, he was leaving anything that could be considered kung fu in the dust. Chan was ready to move on to a more complicated form of cinema, with a broader range of storylines and action set pieces.

Young Master did, however, set many precedents for the beginning of Chan’s personalized film legacy. The fight scenes were some of the most intricately choreographed sequences he had done. Every scene showed Chan’s physical prowess. With the finale making Young Master a classic, it broke all box office records in Hong Kong, and it defined Chan’s new market in Japan. This was also the first time that Chan had released a film during the Chinese New Year, whose date ranges from the end of January to early March. From then on he would use Chinese New Year as the date for everyone around Asia to know that a new Jackie Chan film would be released.

Chan puts his gymnastic skills to the test against Whang’s two henchmen, Lee Hoi-san (left) and Fong Hak-on (right). (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Chan began assembling his own crew with Young Master, as well. He wanted to create his own team of young, energetic players whom he could plug into any of his films in various roles. Fighting, stunt work, and acting were requirements.

Fong Hak-on was the first person that Chan brought onto his personal team. Fong, a veteran of many Shaw Brothers films, has always played a villain. He can be seen over the opening credits of Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow and Chan’s first fight in Drunken Master. Fong and Chan collaborated as fight choreographers on the project The 36 Crazy Fist (1979), as a favor to Chan’s longtime director pal Chen Chi-wah. Fans can see a fifteen-minute documentary of Chan and Fong choreographing The 36 Crazy Fist tacked on to the video of a poorly produced kung fu flick entitled The Young Tiger. (In several shots Chan has a cigarette hanging out of his mouth.) Young Master’s fight choreography credits listed only Chan and Fong, since this was before Chan devised an entire stuntman team. Also, Fong plays one of Master Whang’s two lackeys in the film, and he went on to play the lead fighter in Police Story (1986). Fong is in the background of most of Chan’s films, but after Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, he left Chan’s team to pursue his own career as an action director.

Another Shaw Brothers actor, Cheung Kanin, was the other early cornerstone of Chan’s team. Assuming the stage name Tai Po, meaning “bad boy,” his characters would always be mischievous whether he was one of Chan’s partners in crime or not. Although Tai Po had martial arts training, Chan wasn’t necessarily using him as just another fighter; he was one of Chan’s first recurring background players. In Young Master Tai plays one of Chan’s fellow students in the school.

Young Master was the first film to contain a track sung by Chan. Interestingly enough, the song never made it into the Chinese version, but when the film was released internationally, “Kung Fu Fighting Man” can be heard over the end credits. Chan’s English was almost nonsensical at this point in time, but one can make out most of the silly lyrics. This would become a trademark for Chan: All of his later directorial efforts contain a new ode to heroism sung by Chan during the credits. They would all be in Chinese.

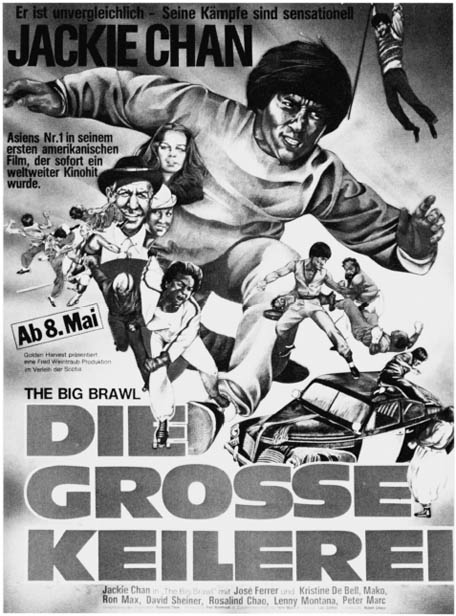

With the success of Young Master, Chan was ready for something modern, and that meant going to America. Bruce Lee’s success had given Golden Harvest a future in the international market, and Raymond Chow was just itching to try again with Chan. In a calculated move, he met with his Enter the Dragon cohorts, Fred Weintraub and Robert Clouse, who came up with the project Battlecreek Brawl, later retitled for Western audiences as The Big Brawl. Chan was paid one million dollars for his role, as he began a two-year tour of duty in America.

Critics often find Chan’s first American effort lackluster, but he learned a few things—especially the English language. While Bruce Lee was formally educated in America and had no problem with English, Chan was just the opposite. He spent two years in Los Angeles studying with a Beverly Hills language coach seven hours a day. His secondary training was watching television—he has often credited commercials for teaching him simple American phrases and ideals.

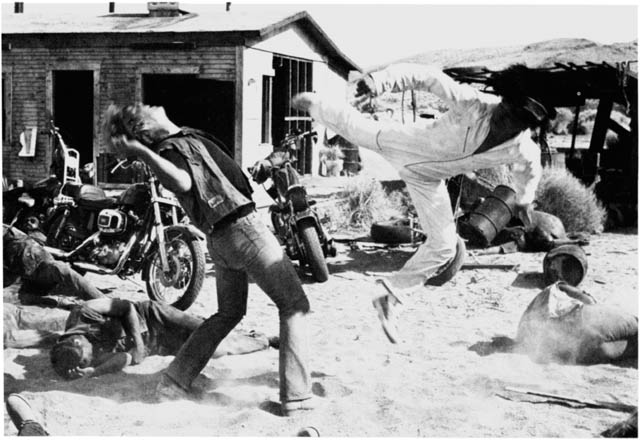

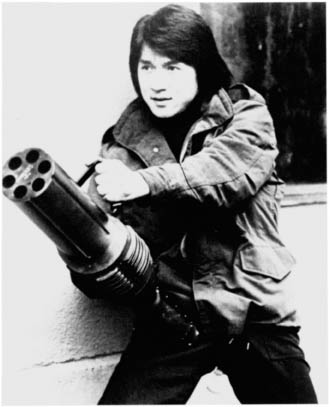

Chan makes the best of a Hollywood fight scene. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Chan and Mako in a lobby card for The Big Brawl (1980). (By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Chan’s first bout with America does show his charisma and physical abilities, but The Big Brawl sets up limitations on both. A third limitation was a structured script. While Robert Clouse’s treatment uses some of Chan’s underlying qualities, such as playing an underdog, it proves that most of what makes Chan so amazing is his on-the-spot invention. When Bruce Lee, Weintraub, and Clouse collaborated on Enter the Dragon, Lee was a part of the team, coming up with many ideas on the set and choreographing all of the fight scenes. For The Big Brawl, Chan was just an actor. Unlike Lee, he had no experience with Hollywood’s ways, and he wasn’t afforded the chance. “I knew that racism was alive and well and living in Hollywood in a very aggressive way,” points out Ric Meyers. “I knew that they were treating him like this little Chinese curiosity instead of the true giant that he was. They were treating him like a little man that they were doing a favor for.”

Ric Meyers remembers “talking with Jackie after The Big Brawl, and he told the famous story about how Robert Clouse told him to go from the door of the car to the door of the restaurant. ‘Okay, I jump out, somersault, cartwheel, then I flip around.’ ‘No, Jackie, no, no, no,’ the director said. Finally, Jackie says, ‘Nobody pays money to see Jackie walk.’ ”

German ad slick for The Big Brawl. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

Whether he liked it or not, Chan was America’s new Bruce Lee, and veteran fight choreographer Pat Johnson was supposed to ensure that. The Big Brawl’s opening credit sequence has Chan leaping into the air in slow motion, screaming with a long yelp as he throws a few kicks and punches. The movie is set in Chicago during the 1930s, with Chan playing a cocky do-gooder whose only ambitions are to marry his girlfriend and compete in roller skating races. He is put to the test when his father is forced to pay protection money to some local mobsters in order to operate a restaurant. Although he is forbidden to fight, Chan comes to his father’s aid by fighting off three of the mobsters in and around a car. The entire scene was filmed with a master shot giving only one view of the action. This is a great limitation on Chan’s abilities since he has little room to work with, and most Hollywood action directors do little else except move the camera. Segment shooting—where a prescribed set of movements are encompassed in one shot—best displays the dynamism of Chan’s action. With only a master shot to move in, Chan had to work his magic one-dimensionally.

Jackie Chan’s Real-Life Brawls

Even today, when someone says “kung fu,” the first thought that comes to mind is Bruce Lee. On- and off-screen, Lee wasn’t plagued by Chinese stereotypes. He wasn’t a docile, subservient being. He was a man in control of his destiny. He was in command of everything he did and had no problem fighting to get there. On numerous occasions Lee was put to the test: first, for teaching the gwailo (slang term literally meaning “white ghost,” used to describe non-Asians) kung fu; second, for proudly walking the earth—almost imposing the fact that he was a grand example of what a martial artist can be. And challenged he was, but each time Lee would prove to be the victor.

This was Lee’s way, not Chan’s. In 1980, when Chan was brought into the public eye as the new “master,” it was only a matter of time before he, too, would be tested. Arriving in Detroit, Michigan, Chan’s first such encounter would take place in the front of city hall, whose front door was hung with a banner reading “Jackie Chan—Master of Kung Fu.” The crowd became animated over this proclamation, and Chan felt uneasy. While Chan was in the midst of a kung fu routine, a man jumped up onstage and yelled to Chan a question concerning an attack. The event’s promoters stood silently. The man suddenly threw a punch toward Chan, but a well-placed kick to his legs by Chan’s left foot sent him to the ground before he could get even close.

That fight was over, but Cincinnati, Ohio, brought on yet another. On a local television show, Chan was to demonstrate a maneuver to escape a choke hold from behind. Unlike in rehearsal, Chan’s six-foot partner squeezed as hard as he could, nearly suffocating Chan in the process. With a quick elbow jab to the ribs, Chan spun his body around while sending his opponent to the ground before him.

Finally, in Portland, Oregon, a man walked right up to Chan and challenged him to a fight. After Chan declined, the man held out his hand for a friendly shake. Feeling his hand grasped forcefully, though, Chan readied himself in a defensive position and simply increased the pressure of his own grip. Noticing a quick movement of the man’s left hand, Chan grabbed his thumb and bent it to his wrist, sending him to the ground.

When Chan came to America again in 1995, no one dared make such a challenge. With his bodyguard, Kenneth Low Houi-kang, and usually a policeman, Chan could just smile for the cameras and be charming without looking behind his back.

Chan’s brief encounter catches the eye of the mob boss, who is looking for a new fighter to bet on in an “everything goes” competition called the Battle Creek Brawl in Texas. Chan is forced to participate in the event after being trained under the watchful eye of his uncle, played by Asian character actor Mako. The linear script contains few surprises, and with all of the action scenes filmed with master shots, audiences can see that Chan can do something—they just don’t really know what it is. Instead of fighting tae kwon do experts or gangs of skillful kung fu fighters, Chan merely throws around a bunch of sluggish, professional wrestler types.

The Big Brawl did give Chan the opportunity to appear on numerous American talk shows, such as The Mike Douglas Show, That’s Incredible, and Today. Appearing with Christopher Reeve and Melissa Gilbert on The Mike Douglas Show, Chan’s lack of English had no apparent effect on his natural, good sense of humor. When Mike Douglas asked him if he stayed in contact with his parents, Chan replied that his parents would send him letters with money in it. “Well, didn’t you miss them?” Douglas persisted. “Ah, I miss the letter!” Chan quickly rejoined. The audience roared in laughter, but before they could settle back down in their chairs, Douglas asked Chan if he could swat a fly that came into sight. Chan pretended to swoop up the fly, and before Douglas can say another thing, he mimicked throwing it into his mouth. If anything, Chan made people laugh, and this sense of comedy was his only defense against the “martial arts actor” label. The show ended with Chan performing a freestyle kata (a practice form in martial arts composed of prescribed movements) and teaching Douglas the one-inch punch. On That’s Incredible, he performed the same routine, and all of the questioning had to do with comparing Chinese food and women to American.

Chan would next appear in two Cannonball Run films made in 1981 and 1983. “I remember totaling up the costs for the cars and the actors and finding that I needed more money,” said director Hal Needham. Needham met with Golden Harvest and arranged for the films to be made as coproductions, giving Chan yet another opportunity to find an audience in America.

In the first film, Chan and Michael Hui, Golden Harvest’s comic sensation, play a pair of Japanese car drivers who enter the competition. The purpose of the film was to showcase as many stars as possible, such as Burt Reynolds, Farrah Fawcett, and Dean Martin, and let off a series of sight gags and jokes within a loose structure. Needham had heard of Chan but knew nothing of what he could really do, and with such an orgy of stars, Chan and Hui needed to do more than just make their presence known. After seeing Chan demonstrate his agility for the first time, Needham agreed to let him pretty much run his fight the way he wanted. Almost the way he wanted: Chan couldn’t convince Needham to let him have a month-long shoot! In his fight, Chan has a couple of moments, most notably with motorcycle gang member Peter Fonda. Without the time to detail the fight choreography, however, Chan comes off as being just another guy who can throw a kick.

Chan’s only substantive scene in The Cannonball Run was fighting a few bikers led by Peter Fonda. (By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Nevertheless, Chan meshed well with the Hollywood stars. In a documentary on Cannonball Run, Burt Reynolds commented, “I think he’s one picture away from being a legend like Bruce [Lee] was.” A dialogue coach would go over every line with Chan, since his English speaking ability was still lacking “Most of my actors would spend their time in their trailers if they weren’t in a scene,” recalled Needham, “but Jackie would be hanging around the set, trying to learn everything he could about how we do things in America.”

Cannonball Run did fairly well in America but met with a lukewarm response in Hong Kong. However, the Japanese market took very well to the film, so Golden Harvest opted to use Chan for the sequel. The emphasis was on big stars and fast cars, though, and Chan barely set foot out of his superinjected vehicle, where he was paired up with Richard Kiel, “Jaws” of James Bond fame. Given little to do, Chan was just another face on the screen. There were two short martial arts sequences, but everyone beats up the bad guys—including Dom DeLuise in a superhero costume!

“I don’t give a damn what nationality you are; if you watch him, you gotta like him!”

—Hal Needham

In between the two Cannonball Run starfests, Chan would return to Hong Kong and mark his first real effort in what would be the Jackie Chan genre. The film industry there was still clinging to the very late Ching Dynasty, setting virtually all kung fu films in the late 1800s to early 1900s. Unable to truly break out of the period mold, Chan’s effort was called at first Young Master in Love, a rather melodramatic title that was later changed to Dragon Lord. The uneven script once again focuses on relationships while tugging at traditional values.

As the son in a rich family, Dragon (Chan) has virtually no responsibilities except for learning from various tutors imposed by his strict father. He pays no attention and opts for chasing girls and competing in bizarre sporting events with his cousin Cowboy, who’s given this nickname because his father’s import business centers on Western culture. The film’s initial premise of love superseding friendship quickly disappears when Chan stumbles upon a band of thieves scheming to sell China’s ancient treasures for profit. Chan doesn’t really see a problem with this until he befriends one of the thieves, who wants to put a stop to them. After three skirmishes with the group, Chan once again faces Whang Inn-sik, who plays the chief of the group.

A film about friendship: Dragon Lord. Cowboy is played by longtime stuntman and friend Mars. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Despite the setting and the costumes, Dragon Lord has nothing to do with martial arts nor anything that would appear in Chan’s earlier kung fu films. “The story focuses on the relationships with his friends, sort of an ode to his Peking Opera days,” says screenwriter Edward Tang. “Friendship and competition has a very interesting bond, and I wanted to bring this out into the open.” By focusing on typical problems with friendship and love, the action sequences aren’t rigid tests of fighting ability but natural tests of physical ability. Each scene in the film is a set piece instead of just another fight.

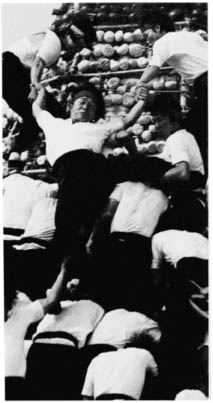

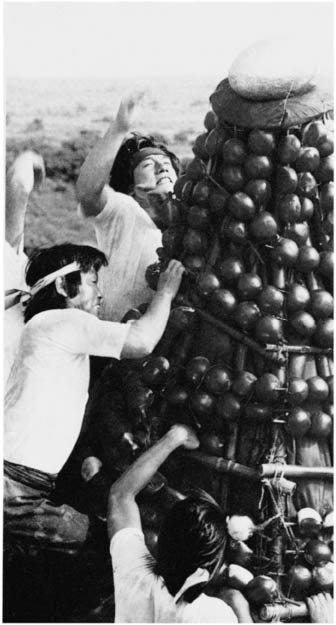

The opening action scene is a “king of the mountain” exhibition, with groups of young men climbing to the top of a forty-foot structure to claim a golden egg. Once back on the ground, the person with the egg must fight his way to his table and place the egg inside of a pouch. “We had over ninety stuntmen in that scene, and everyone got hurt,” remembers Tai Po, who played one of Chan’s youthful friends. Chan’s direction shows off these wiry stuntmen executing kicks, flips, and flops to obtain the egg in breathtaking wide angle shots.

The “King of the Mountain” competition. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

(By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Chan goes for the golden egg. (By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

The finale of the second action sequence has been etched into Chan’s résumé as containing the shot requiring the greatest number of takes. Chan is participating in a sort of soccer game, the players moving a shuttlecock back and forth like a Hacky Sack, using knees, feet, arms, heads, and any other body part to knock the feathered cork into the net. The game begins to look bad for Chan’s opponents, whose missed kick gives him the opportunity to win the game by kicking the shuttlecock some thirty feet into their net.

The audience clearly sees Chan performing this feat. Since the majority of the game is left in wide shots with few cuts, timing and coordination had to be in perfect synch to make this last shot work. It boggles the mind to think how long it must have taken to shoot, for all the complex plays to work and Chan’s incredible game-winner to go in. What the audience doesn’t know is that it took one thousand attempts to get it right!

When Chan cleverly tries to send his love a letter via kite, the wind carries it to the roof of the bad guys. Before he can snatch it back, the roof scene becomes yet another set piece, with Chan hopping around to avoid a series of well-placed spears that come crashing up through the shingles. In some instances, Chan would barely rise up from the roof, just barely being missed by the tip of a spear—all without quick editing, a further example of breakneck timing. Shortly thereafter, Chan tries once again to talk with his love but is interrupted by two of the thieves, who push him to the edge. Jumping through wooden fixtures, climbing up columns, and literally running up the wall to clown around with his foes, Chan shows his intricate choreography to be more playful than the normal, structured fighting of his previous film efforts.

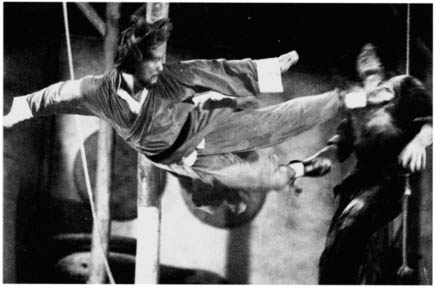

Chan didn’t learn his lesson in Dragon Lord, so here he is again, fighting Whang Inn-sik. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Dragon Lord represents Chan’s new direction of bringing action to the screen, and the finale can be said to give the first taste of what makes a Jackie Chan fight sequence so compelling to watch. When Whang beats up Cowboy and asserts his fancy footwork on Chan, there is an excitement that quickly burns every other Chan fight scene before it. During the entire film Whang’s face is somewhat blocked by other variables on the screen until his duel with Chan, when the camera jump zooms in on the fact that one of his eyes is completely white! By giving the villain extra flavor, the fight starts rather abruptly. Inside of a feed mill Chan runs at his opponent without any type of formal movements, just swinging arms and feet. Of course, Chan undergoes rather than inflicts more punishment until they get to the second story of the mill. In a unique form of obsession, Chan is determined to knock Whang to the ground below. At one point, he is standing on the outside of a railing and tugging at Whang relentlessly, even though getting his wish would mean he would fall, too.

(By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

The scene is important because it shows that Chan’s action character is not immune to punishment but merely accepts it as part of the job. In one amazing shot, Chan is kicked to the ground below, only to land right on top of Cowboy, played by Mars. “Jackie and I both went to the hospital with bruised backs,” recalled Mars in thinking back to the scene. The most amazing highlight is when Chan jumps down a feed chute and kicks Whang a dozen feet away. Doubling for Whang, a stuntman stood idly by on top of a bag of grain and let Chan push-kick him. An elaborate pulley effect propels the stuntman into the air, where he performs a backflip before flopping to the ground. Chan immediately jumps on his back, then leaps onto stacked bags of grain, and does a backflip, landing on Whang’s back again! As if that wasn’t enough, Chan smothers Whang with more grain bags until he’s finished off. The mixture of realistic fighting and amazing stuntwork denotes the classic Jackie Chan action scene, and this feed mill sequence was the first.

For Dragon Lord Chan added two more men to his team of stuntmen, dubbed Sing Kar Pan, known to the rest of the world as Jackie’s Stunt Team. One of them, Cheung Wing-fat, first met Chan in 1967 during his own tour of duty in a Peking Opera school. It was a regular practice for students of different schools to mingle and discuss the tricks of the trade. Cheung and Chan became good friends, and Cheung found work with the Shaw Brothers like many other young opera students of his age. Audiences wouldn’t know him by the name Cheung, since he adopted Fwa Sing as his Chinese stage name, which translates to Mars in English. He assumed the oddball name Mars because he thought it fit his oddball facial features. “Mars is the comedian of the group, and he always has a joke to tell on the set,” said Tai Po. Mars also serves on the committee for the Hong Kong Suntman Association and has worked with Chan on nearly every single film since, as well as contribiting to Sammo Hung’s films (although in recent years, he has worked solely as a stuntman).

Since Dragon Lord was shot in Taipei, Taiwan (the original location was Seoul, Korea, but it proved too cold), Chan got to see many different stuntmen in action, and from them he added Benny Lai Keung-kuen to the group. Although he can be seen in Dragon Lord, Police Story, and Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, Lai is best known to audiences as the animalistic, mute fighter who tangles with Chan in the climax of Police Story II.

Dragon Lord was Chan’s decisive move toward more Westernized ways, leaving much of the Chinese culture to simply blend into the background. The Cowboy character is an obvious signal; he and Chan are hunting with Western guns when they come across the film’s thieves. Chan seems more concerned with meeting girls, playing with his friends, and just plain goofing off than meeting his Chinese obligations as a son.

Chan’s character doesn’t seem to care about Chinese history or even the preservation of rare artifacts, which is what the thieves are stealing. (Chan came up with the idea of artifact theft while running through the many plot synopses at Golden Harvest.)

But what about kung fu? In the beginning of Dragon Lord, Chan performs a few freestyle kung fu forms under his father’s watchful eye. Anything honoring his heritage, in fact, is done just to please his father. The audience can see that Chan is adept at martial arts, yet he can’t seem to use any of it when faced with a violent situation, where Chan trades in the formalized movements of kung fu for his acrobatic fighting skills.

As evidence that the original script was completely devoid of the artifact plot, the last shot has Chan and Mars holding up an inscribed banner that reads, “I won’t love girls anymore”—as if this was a lesson to be learned about the pitfalls of friendship. Dragon Lord would have been quite a different film if it had kept to the original story without the fight sequence at the end.

Dragon Lord did very poorly in Hong Kong, but it proved to have the necessary staying power for the Japanese market as well as internationally. Chan’s new take on fight choreography did not win the Best Action Design award at the first annual Hong Kong Film Awards. Instead, critics gave the award to Sammo Hung for his work on the groundbreaking wing chun film The Prodigal Son. With all of the essential ingredients in place and a need to move his self-created genre into a modern setting, this was Chan’s final period film until Drunken Master II twelve years later—when he again uses theft of Chinese artifacts as the film’s premise.

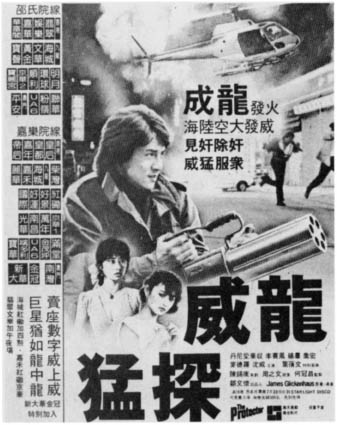

In 1985, three years after Dragon Lord, Chan was ready to try another starring role as an American action star. Although the Cannonball Run films were popular around the world, Chan had only a small piece of the action. He yearned for American stardom—but not in a period piece like The Big Brawl or with a bit part as in Cannonball Run. Impressed with his previous work, a Golden Harvest producer felt that James Glickenhaus could give American audiences the Chan they were supposed to know. Based on a script by Robert Clouse, The Protector is a modern-day action vehicle appropriate for Charles Bronson, Clint Eastwood, and—Glickenhaus apparently thought—Jackie Chan. The film is everything that Chan isn’t, but it’s a great film for analysis because Chan re-edited it and shot new footage for its release in Hong Kong. The comparisons between the two are astonishing.

The Protector (1985). (By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Director Glickenhaus understood Jackie Chan, or so he thought. He knew about Chan’s martial arts skills and his use of comedy in keeping violence out of the action, but Glickenhaus was an established director of B-grade action flicks like The Exterminator. His style was pedestrian Hollywood filmmaking, and his script for The Protector was typical of his work. Aside from shooting Chan as if he were Charles Bronson, the main differences between Glickenhaus’s American Protector and Chan’s Hong Kong version are the male-oriented characteristics Hollywood has given the action genre, including nudity, foul language, bloodletting, and male bonding. The American version contains all of these attributes, with Chan playing a New York cop who gets in trouble with the force, only to be teamed up with a new partner, played by Danny Aiello. When the host of a fashion show they are attending is kidnapped, Chan and Aiello are sent to Hong Kong following a hot tip. The kidnapping turns out to be nothing more than the move of a pawn set in a larger game between two drug lords fighting for control.

Chan and Glickenhaus did not get along on the set, and the experience left him in dismay as to whether he could make it in America or not. On several occasions Glickenhaus would let his assistants take over while he stayed in his trailer. Even with this kind of mishandling, no one would listen to Chan, who had his own ideas on how the action had to be filmed. With his hands tied, Chan merely performed the movements Glickenhaus wanted until the latter returned to the States.

The Protector. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

With the chance to recut the film for the Asian market, Chan enlisted Aiello and martial artist Bill “Superfoot” Wallace to reshoot the ending as well as film additional scenes. Expletives are common in standard action fare, so Chan resubtitled the film with whatever he wanted. So when tough guy Chan has to use tough guy language, like “Give me the fuckin’ keys!,” Chan merely changes it to “Give me the keys!” American slang was also excised from the Asian cut of the film for obvious reasons.

The big motorcycle jump in The Protector. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

And what exploitive action flick would be complete without a little “T ‘n’ A”? You won’t find any in a Jackie Chan movie, though (except for the occasional comic shot of Chan’s derrière). When Chan and Aiello first arrive in Hong Kong, they are led to a massage parlor for information. The American version includes a strip scene and several sexual innuendoes, all of which are perfunctory devices to set up a fight. Chan cuts all of this from the Asian print. The most gratuitous scene is the final onslaught on the drug bosses’ operation, where four female workers are completely naked. Many drug operations do make their employees work in the nude to prevent stealing, but it’s absurd to think that The Protector or any other action film would try to adhere to anything realistic. Chan cuts every shot of nudity from the film, even shooting new footage of a fully clothed actress mixing heroin for the sake of continuity.

The main difference between the two versions, however, is in the action. Chan adds three action scenes and retools the final fight to the standards set by his Hong Kong films.

Furthermore, Edward Tang was brought in to clean up the American version, and he added two additional subplots to create more action, making the film more interesting. The Chan character brings a mysterious Chinese coin to Hong Kong in search of a link to the kidnapping. The Asian version makes better use of this device as it pairs Chan up with Hong Kong singer-actress Sally Yeh, who plays the daughter of the deceased owner of the coin. In their initial meeting, which takes place in a dance studio, Chan has a brief fight in a connecting gym with two of the studio’s dancers. Yeh’s character is soon able to explain much of the convolution unresolved in the American version, and she also sets up a second action sequence, which takes place in her apartment. It isn’t much: Chan must diffuse a bomb and shoot an intruder at the door.

The American version contains a strain of plotting that deals with a kindly, old Chinese merchant who is connected to the coin and to the Hong Kong drug lord. When Chan and Aiello quiz him on the whereabouts of the kidnapped girl, he says he will find out. He is killed thirty minutes later—gruesomely impaled to a burning ship in which he does business. The merchant’s daughter is left to blame Chan for his death.

In Chan’s hands, this is yet another chance to add a fight scene. Chan took every opportunity to add some pizzazz to the original film. The Asian version brings the merchant to meet a contact in a harbor, but he is interrupted by the drug bosses’ men and Wallace. Chan’s stunt-man Fong Hak-on is clearly seen, and Wallace gets a chance to show off the karate skills that made him famous in the ring (Wallace had earlier played Chuck Norris’s nemesis in A Force of One). Chan and the merchant’s daughter then show up to meet the contact, as well, only to find her father and the contact left for dead. The daughter’s reaction is much more severe, and it gives Chan more reason to put a stop to the drug lord’s activities.

As a side note, Moon Lee, who played the merchant’s daughter, could not deliver her lines well enough in English, and the Chinese dubbing proved to make her scenes stronger. She would become one of the biggest female martial arts stars in Hong Kong just two years later with Angel, after receiving extensive training.

The most interesting differences between the American and Chinese versions is in the final fight between Chan and Bill Wallace. The Glickenhaus version is rather short, considering it was supposed to be a classic matchup, and it’s shot in typical Hollywood fashion. Wallace throws a kick, Chan blocks; Chan throws a punch, Wallace throws another kick; and so on.

Understanding real combat, Chan runs his version quite a bit differently. The choreography is more intricate, with numerous blows exchanged from both sides at once. Although Chan uses some of the original footage, he adds the showy acrobatics that have made him the star he is today. The most memorable moments come when Chan is fighting Wallace next to a steel fence. In one shot, Chan clings to the fence, does a backward flip over Wallace, and pulls him over the top. Then, seen from a different angle, Chan is kicked into the fence, bounces off of it, and powers right back at Wallace in one incredible take! It’s this kind of artistry that Hollywood doesn’t understand.

Hong Kong newspaper ad, which shows Sally Yeh. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Other comparisons of the two versions’ fight choreography, direction, and editing reveal vastly different cuts of the film, and Chan’s cut easily comes out ahead. After winning in the early going of the fight, Wallace comes back with a buzz saw. The original version is shot with nice, wide angles that reveal Wallace’s slowness and lack of maneuverability with the saw. Chan reshot the sequence, adding quick cuts to speed up the action and give it the intensity that it needs. Chan’s version also includes the more accented sound effects for kicks and punches, compared to the realism of the American cut. Glickenhaus openly admitted to shooting the film with masters, which he backed up with different shots. One master shot of Chan kneeing an opponent in the face was so bad (his knee doesn’t even come close!) that Chan just takes the sequence out altogether. Also, Glickenhaus generally didn’t want to speed up the film, but there are several instances where he does speed up part of a shot. This exposes the technique to the audience, when the fast section is sandwiched between sections at regular speed!

If The Protector had had a lighter tone like the one in The Big Brawl it might have been bearable. Instead, it unforgivingly turns Chan into a stone-faced “action hero,” really bringing to light his big nose and misuse of the English language as he delivers serious lines.

The Protector soured Chan on Hollywood: he has gone on record in Hong Kong declaring that he doesn’t care about the American market anymore. But the desire for American success and stardom was merely dormant—it couldn’t die, not in a man who can’t walk away from a challenge. It would take almost a decade for Jackie Chan to be a household name in America.